18 Jul 2010

Tosca at Orange

There was a time when the likes of Luc Bondy and Francesca Zambello staged operas for the Chorégies d’Orange in its famed Théâtre Antique.

There was a time when the likes of Luc Bondy and Francesca Zambello staged operas for the Chorégies d’Orange in its famed Théâtre Antique.

No more. In recent years staging responsibilities have been given to the default directors at small opera houses in the south of France with passable to dismal results.

The Théâtre Antique is a magnificent theatrical vestige of France’s Roman past. These days it is home to this small opera festival — there are two performances each of two operas in late July and early August. The catch is that the stage is 150 feet wide and the amphitheater seats 9000 people. It is a small festival of big, very big operas.

However this summer both operas are relatively small — Puccini’s Tosca and Gounod’s Mireille. While Tosca is obvious repertory to attract an audience of 18,000 people, it is still an intimate opera even though its music is big and its story shocking. Mireille is delicate music to an innocent little love story by Provence’s poet Mistral.

The suspicion is that messieur Raymond Duffaut, general director of the Chorégies has lost his mind. Not just because Mireille cannot possibly attract an audience of 18,000 people (famous last words), but also because he entrusted Tosca to the least able of these local stage directors, one Nadine Duffaut (yes, his wife).

The suspicion is that messieur Raymond Duffaut, general director of the Chorégies has lost his mind. Not just because Mireille cannot possibly attract an audience of 18,000 people (famous last words), but also because he entrusted Tosca to the least able of these local stage directors, one Nadine Duffaut (yes, his wife).

The best operas at Orange have been epics and spectacles, where armies clash and jealousies rage. The best operas have spectacular endings, as examples the shooting real flames of Norma’s funeral pyre or even the huge projected flames of Azucena’s funeral pyre, not to mention the transformation of the Turandot chorus into a dragon. The back wall of the Théâtre Antique’s rises 150 feet — one had high hopes for Tosca’s leap.

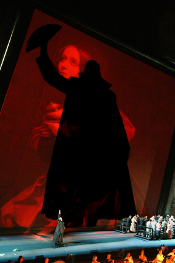

Mme. Duffaut chose the Mary Magdalene painted by Cavaradossi for the Attavanti chapel as her primary image. Magnified a thousand times into a huge set piece this biblical sinner oversaw all in some inexplicable irony. Though in the last few seconds the surface cracked and checkered (a black and white projection onto the painting) as Tosca walked through a slit in the bottom. So much for spectacle.

Mme. Duffaut attempted to use very nearly the entire width of the stage in her staging with the result that it took a lot of time for any of the opera’s protagonists to get from one chapel to another, from Scarpia’s desk to his chaise longue, etc. Conductor Mikko Franck did his best to accommodate these extended distances with tempi so slow that they were just plain deadly (in fact in section D alone paramedics had to remove three opera patrons on stretchers during the performance).

Mme. Duffaut attempted to use very nearly the entire width of the stage in her staging with the result that it took a lot of time for any of the opera’s protagonists to get from one chapel to another, from Scarpia’s desk to his chaise longue, etc. Conductor Mikko Franck did his best to accommodate these extended distances with tempi so slow that they were just plain deadly (in fact in section D alone paramedics had to remove three opera patrons on stretchers during the performance).

The Orchestra Philharmonique de Radio France loved this Finnish maestro, apparent from the foot stomping in the pit for every arrival and departure of Mo. Franck. Let us attribute this love to the maestro’s encouragement that they play as loud as they possibly could — an unusual pleasure for a pit (or any) orchestra. But even the orchestra was overcome by the slowness, manifest by frequent premature entrances.

Mme. Duffaut updated the opera to the Fascist era, giving costumer Katia Duflot (ubiquitous in these parts) yet another opportunity to dress singers in over-designed costumes extolling le look rather than defining le caractère. Tosca entered in a white shin length afternoon dress splashed with huge purple flowers, and simply disappeared within it. In the second act she was in a huge red satin evening gown with an exaggerated train that stood on its own dwarfing its wearer and hindering her movement.

Needless to say Roberto Alagna held the stage as Cavaradossi as did Falk Struckmann as Scarpia. Alagna is a natural singer and a natural actor, Struckmann is a pro. Neither need nor probably want a stage director. Except that there are scenes between protagonists that have to be shaped. Mme. Duffaut’s abilities apparently do not extend to imposing direction on such artists.

On the other hand Catherine Naglestad, the Tosca, has had a brilliant career working with some of Germany’s most gifted directors. Perhaps she could have been coached into embodying a temperamental diva. Left on her own she could not master the quick, nervous, powerful moves that she needed to manipulate her grand red dress. Nor unfortunately does she possess an imposing vocal presence.

The Angelotti of Wojtek Smilek and Spoletta of Christophe Mortagne were well realized within these reduced circumstances. The roles of the Sacrestan and the Shepherd were embarrassments to the profession.

This Tosca fared equally poorly in the French press. Let us not forget that opera at Orange can be good, justifying the steep climb to your seat in brutal summer heat.

Michael Milenski