Above all, there is no evidence that they would

compete for queen Rodelinda, who instead was exiled to Benevento with her

little son Cunincpert and lived peacefully there until Perctarit, after finally

recovering the throne, summoned her back to the kingdom’s capital

Pavia.

Turning into melodrama characters those practical barbarians, more

interested in power than in romance or bloody vengeance, was the endeavor of

such Baroque playwrights as the French Pierre Corneille and the Florentine

Antonio Salvi. The latter’s 1710 libretto for Giacomo Antonio Perti

(Rodelinda, regina de’ Longobardi), drastically pruned by Nicola

Haym for the London stage, was set to music by Handel in 1725. It immediately

proved a resounding success, also thanks to a cast including soprano Francesca

Cuzzoni in the title role, the legendary Senesino as Bertarido, and some of the

best singers available in the side-roles: tenor Francesco Borosini, bass

Giuseppe Maria Boschi, and alto castrato Andrea Pacini.

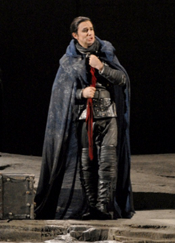

Franco Fagioli as Bertarido [Photo by Laera]

Franco Fagioli as Bertarido [Photo by Laera]

The present staging in Martina Franca, a festival traditionally claiming to

“authentic” performing practice, plunged the romanticized

18th-century music drama back into the darkest Middle Ages, or into a

“Middle Ages next-to-come”, as phrased by director Rosetta Cucchi.

At least visually, through the combination of muddy and disheveled landscapes

with costumes (by Claudia Pernigotti) featuring leather, rags, metal

decorations, and heavy-duty boots. Entertaining enough, but how much

“authentic” is questionable, if only one checks Senesino’s

portrait as Bertarido in the flamboyant livery of a Hungarian haiduk,

as painted by John Vanderbank in 1725. At the most, this is

Regietheater that dare not speak its name, a compromise likely to

dissatisfy modernists and authenticists alike.

The show’s musical side was far more convincing, with the Swiss

conductor Diego Fasolis succeeding to elicit from the festival orchestra

— equipped with modern instruments plus harpsichord, theorbo and Baroque

flute — a sound that was both luscious and historically informed. Within

an evenly balanced company, the Argentinean alto Franco Fagioli (Bertarido)

towered for projection, agility, seamless transition between registers,

unfailing musicianship. His manly color and stage charisma may set a new

standard among countertenors. As Rodelinda, mezzo Sonia Ganassi tended to

underact throughout and suffered some strain in the upper register. For her

convenience, a couple of high pitches were transposed an octave lower, and her

whole climactic aria “Ombre, piante” was set in G minor instead of

the original B minor. Nevertheless, she sang with an elegant restraint hitherto

unnoticed in her main repertoire, stretching from Rossini and Donizetti to

Massenet.

Her sister-in-fiction Eduige (the established Baroque specialist Marina De

Liso) outplayed her as to style awareness, consistently unfolding hot

temperament and fanciful coloratura. On the contrary, both the villain

Grimoaldo (Paolo Fanale) and the arch-villain Garibaldo (Gezim Myshketa) were

absolute beginners in the field of early opera, yet delivered their fast runs

and stalking utterances pretty nicely. A further pleasant surprise was the male

alto Antonio Giovannini, who lent the loyal Unulfo mellow color, tasteful

da capos and lots of acting stamina, particularly in the alternative

E-minor version of “Sono i colpi della sorte” after the Hallische

Händel-Ausgabe (HHA).

To many affectionate Handelians, the opportunity to hear this and some more

passages restored to the composer’s final intentions was a novelty. Yet

the claim of a “world premiere in Andrew V. Jones’ critical

edition” is mere pressroom hype. The actual premiere with HHA material

before official publication was in Glyndebourne 1998, followed by the Göttingen

Händel-Festspiele in 2000 and sundry houses worldwide. Anyway, the new artistic

manager in Martina Franca, Mr. Alberto Triola, can rightfully boast for

bringing to attention a dramatic masterpiece which, despite its Italian

subject, was hitherto neglected by the major opera theaters in Italy.

Carlo Vitali