Judith, Esther, Delilah, Bathsheba, Mary Magdalen,

Saint Cecilia, Saint Agatha and their companions were the favorite heroines of

those stories, inasmuch their feminine charms, and their dangerous influence on

men’s behavior, were often graphically described in the librettos.

Manuscript title page of Oratorio di Giuditta © Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

Manuscript title page of Oratorio di Giuditta © Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

La vedova generosa [The Generous Widow] is the recently identified subtitle

for Giuditta, one among the several dozens oratorios written by the Rimini-born

composer Antonio Draghi (1634/35-1700) for the Habsburg imperial court at

Vienna. One may scent therein a tribute to Draghi’s generous employer,

the empress dowager Eleonora Gonzaga, whose musical household in Vienna was

second only to that of her stepson, the music-avid (and amateur composer)

emperor Leopold I. Both Eleonora and Leopold were devout Roman Catholics, much

Italianate in their taste for music drama. Besides opera proper, they invested

a good amount of their time and financial resources on oratorios, a musical

entertainment originally devised by St. Philip Neri to keep people off the

dangerous enticements of secular theaters, but soon transformed into a

“perfect spiritual melodrama”, as abate Arcangelo Spagna, a

theorist, put it in 1706.

Thus the subject of Judith, the ‘generous’ Jewish widow who

delivered her people from the Assyrian chieftain Holofernes by means of

unorthodox sexual warfare, could not escape Eleonora’s attention, nor the

one of an ambitious court composer. Just months after the premiere performance,

which arguably took place some time between Lent 1668 and Lent 1669, Draghi was

promoted from the Empress’ to the Emperor’s service, with a

substantial raise in his salary.

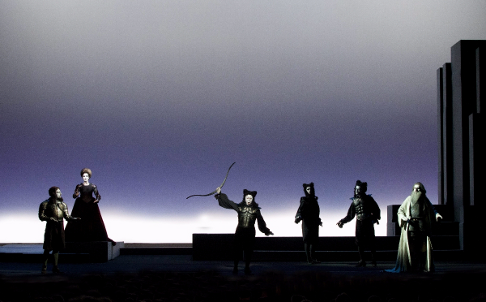

Rimini, Ensemble Seicentonovecento in Draghi’s Giuditta [Photo by Fabiana Rossi]

Rimini, Ensemble Seicentonovecento in Draghi’s Giuditta [Photo by Fabiana Rossi]

So much for the historic background. As to the music itself, Draghi’s

Giuditta stands mid-way between the earlier, Cavalli-style, Venetian opera and

the progressive Neapolitan school launched by Alessandro Scarlatti during the

following decade. The prevailing syllabic recitative is largely peppered with

elaborate florid passages, and most cadenzas soar to eloquent ariosos in triple

time, sometimes with a dance-like lilt. Although just two numbers are formally

labeled “aria” in the manuscript score, there are actually a few

more. While only the final ensemble for the four soloists (Judith, her maid

Abra, Holofernes and the Narrator) brings the caption “da capo”,

two arias for Abra - somewhat of a comic character - are clearly set in the the

‘modern’ ternary form A-B-A`, a daring experiment for the times.

However, the centerpiece is a long and articulate conversation scene between

Holofernes and Judith, totalling nearly one fourth of the entire work.

It’s a red-hot skirmish between the lusty chieftain and his would-be

victim; the former voicing his desire enhanced by heavy drunkennes, the latter

pretending to reciprocate but determined to cut his head as soon as he falls

asleep.

Every manner of compositional devices are employed here, from secco

recitative, through arioso, to outright aria (particularly compelling is

“In dolce calma” for Holofernes, accompanied by a pair of gambas).

Minutes before accomplishing her brave deed, Judith fulfills the dearest

expectation of any early opera-goer: a lament on a descending chromatic

tetrachord, the time-honored emblem for grief and supplication (“Pietà

Signor”).

Such a precious rediscovery was presented in Draghi’s native city as a

special project within the 62.nd installment of the Sagra Musicale

Malatestiana, a major festival series attracting visitors from several

countries. For the third year in a row, Italian and Austrian institutions

joined forces to celebrate Draghi, hitherto an injustly neglected composer of

the Baroque era. Contrary to the current fade for oratorios, the Rome-based

Ensemble Seicentonovecento led by Flavio Colusso didn’t arrange a fully

staged production. The venue, a large 18th-century Jesuit church in downtown

Rimini, offered visual attractions enough. No props, very few movements from

the singers, and passages from period sermons delivered by actress Silvia De

Palma shaped the performance as close as possible to the original conditions:

half private entertainment, albeit in fashionable court circles, and half act

of religious worship. Of course, most credit for the success goes to the music

department. A scanty yet energetic ensemble of two violins, theorbo, organ and

harpsichord accompanied a quartet of vocal soloists conversant both with the

dramatic subtleties of recitar cantando and the virtuosic coloratura of late

17th-century bel canto. Two recognized specialists as sopranos Gemma

Bertagnolli (Giuditta) and Elena Cecchi Fedi (Abra) were complemented by the

up-and-coming bass Luigi De Donato (Oloferne) and by the male alto Antonio

Giovannini, a beginner who seems poised for great things.

Robert Wilson’s fans use to maintain that he deepens and actualizes

the dramaturgy of those operas he happens to stage. In my opinion, either is

hardly true, as the Texan director’s strategy apparently aims at sucking

the life out of any particular opera, freezing down its dramaturgy deep below

the zero point in the pursue of such ritual impassiveness as it was probably

the case with the original Greek tragedy - and still is with the Byzantine

church liturgy, the Japanese Nô, India’s Katakhali or Stockhausen’s

Licht cycle. To be sure, all these theatrical or quasi-theatrical genres are

indented in a respectable religious vision where issues of style, symbols and

formality are paramount, but actualization is obviously ruled out, while

deepths of emotion (if any) are the individual elaboration of their devout

attenders. Whether about Parsifal or Aida, Gluck’s French Orphée or his

Monteverdi forerunner Orfeo, each of Wilson’s productions closely

resembles but Wilson, just as any Mass resembles another Mass, leaving aside

such local details as the language of the sung texts and the music accompanying

them.

The present Ritorno di Ulisse - being the middle panel of a

Monteverdi/Wilson trilogy scheduled by La Scala in co-production with the Paris

Opéra between 2009 and 2013 - sticks to the trend: neither reconstruction nor

deconstruction of the Classic, rather an embalming of it as in a classy funeral

parlour. In the Prologue, the curtain rises on a backdrop mirroring

Poussin’s Le Printemps, an Arcadian landscape inhabited by cute

Disney-esque animals and mimes embodying Love, Fortune, Time and Human Frailty;

too bad that the corresponding singers are plunged in the pit to the

disadvantage of audibility. The core action revolves within hollow spaces

‘representing’ the sea or the Olympus, while the royal palace at

Ithaca, where Penelope is detained in self-imprisonment, is aptly surrounded

with menacing black slates.

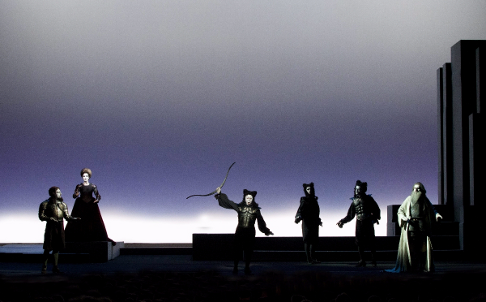

The Bow Contest scene [Photo by Lucie Jansch]

The Bow Contest scene [Photo by Lucie Jansch]

Deities and human beings, the powerful and the destitutes, the goodies and

the villains, look equally unimpassioned and hieratic; static figures striking

enigmatic poses with their white-gloved hands and their pale, heavily made-up,

faces. Most of them, enclosed in Baroque parade armours, are donning lofty wigs

or feathered bonnets. A déjà vu from the court pageants at Paris and Vienna

during the mid 1600s, thus leaving the timeline near the 1640 premiere of the

opera. What else? Colour-coded lighting schemes and sparse but effective props:

Ulysse’s bow, the skeleton of a ship bottom, a Greek idol on a column.

Deaf to the minimal-chic mermaids of Wilson’s staging, Rinaldo

Alessandrini offered a vibrant rendering of the score, despite the many

uncertainties surrounding the actual completness of the unique Vienna

manuscript (the critical edition he lately prepared for Bärenreiter underwent a

few cuts as well as some educated guesses about the instrumental colours). The

continuo players of his Concerto Italiano added authentic flare to a selection

of strings from the Scala pit orchestra. Thus Monteverdi’s explicit

concern for "affetti" (human passions) revived from Wilson's ritual fridge,

also thanks to a company of all-Italian voices where Sara Mingardo and Furio

Zanasi, both accomplished artists beyond strict specialist boundaries, towered

as Penelope and Ulisse. Luca Dordolo made a graceful Eumete, Marianna Pizzolato

a convincing Ericlea, Leonardo Cortellazzi’s Telemaco soared as the

performance progressed. Among the double-bill cameos, basses Salvo Vitale and

Luigi De Donato displayed remarkable panache. I only wonder what happened to

brave Monica Bacelli, who for one time left aside her favorite breeches roles.

Her Melanto, although allowed to display more acting liveliness than any other

character in the show, betrayed an alarming vocal disarray. Hopefully just an

off night.

Carlo Vitali

Cast Lists

Antonio Draghi: Oratorio di Giuditta (1668, libretto by anonymous)

Giuditta: Gemma Bertagnolli; Abra: Elena Cecchi Fedi; Testo [The Narrator]:

Antonio Giovannini; Oloferne: Luigi De Donato. Ensemble Seicentonovecento (on

period instruments). Flavio Colusso, conductor. Chiesa del Suffragio, Rimini,

Italy. Performance of 20 September 2011.

Claudio Monteverdi: Il ritorno di Ulisse in patria (1640, libretto by

Giacomo Badoaro)

Ulisse: Furio Zanasi; Penelope: Sara Mingardo; Eumete: Luca Dordolo;

Telemaco: Leonardo Cortellazzi; Fortuna/Melanto: Monica Bacelli; Il

Tempo/Nettuno: Luigi De Donato; a.o. Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala, with

continuo elements from Concerto Italiano. Robert Wilson, director. Rinaldo

Alessandrini, conductor. Teatro alla Scala, Milan, Italy. Performance of 28

September 2011.