These qualities were affectingly demonstrated during this wonderfully

tender performance by Florilegum of secular instrumental and sacred vocal

music, compositions which unite the best of contemporary French and Italian

conventions.

Couperin was born in 1688 in Paris, the son of Charles Couperin, the

organist St Gervais in Paris. On his father’s premature death, the

organist position passed to Lalande, but François, an early musical genius, was

already deputising for Lalande at the age of ten, and on his 18th birthday he

officially inherited his father’s previous position. Lalande praised the young

man’s innovative 1690 collection of Pièces d’orgue as

“worthy of being given to the public” and helped to establish him

as a Court organist in 1693. In 1700 Couperin acquired the younger

D’Anglebert’s position as harpsichordist at Versailles.

He amassed a notable quantity of superlative harpsichord pieces, which began

appearing in elegantly engraved editions in 1713, following other noteworthy

collections by Rameau and Dandrieu; but, ever the individualist, Couperin chose

to group his pièces into ordres rather than suites, and relied much less on

dance movements than his contemporaries, preferring the freer and more

evocative pièces de caractère.

In his publications of the early 1720s he offered a wide variety of ways in

which the French and Italian styles might be united. As Richard Langham

Smith’s eloquent, informative programme notes state, the works grouped

under the title of Les Nations were “written in the style of

Corelli”; the composer had been “charmed by the sonatas of Corelli,

whose works I shall love as long as I shall live, just as I do the works of

Monsieur de Lully”.

Les Nations is the title under which Couperin published a

collection of four large-scale sonatas; Florilegum presented two – the

earliest of the ordres composed for chamber consort – La

Françoise and L’Espagnole. Director Ashley Solomon, fellow

traverse flautist Andrew Crawford, and violinists Bojan Cici and Tuomo Suni

were expressively supported by Emilia Benjamin’s viola da gamba, David

Miller’s theorbo and the delectable harpsichord playing of Terence

Charistan. The ensemble relished Couperin’s luscious timbres and colours,

responding naturally to the considerable rhetoric of the small dance forms,

exploiting contrast and delighting in the piquant expressive dissonances.

In the slower, more intricate movements, as in the ‘Sarabande’

of L’Espagnole, the meticulous attention to ornament and detail

was impressive, although such details were never allowed to disrupt the

graceful melodic line. String and woodwind articulation in the more energetic

dances was bracingly crisp and fresh; repetitions were constantly

re-invigorated. Rapid passage work in ‘La Gigue’ from La

Françoise was sharply articulated. Despite the fact that these

interpretations were clearly honed to perfection, there was a surprising sense

of spontaneity, as if the reading was unfolding in real time.

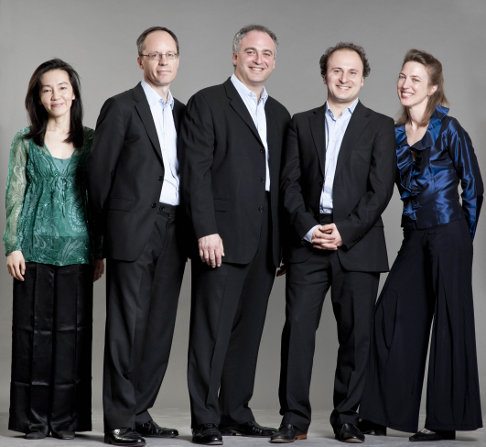

Florilegium [Photo by Amit Lennon]

Florilegium [Photo by Amit Lennon]

The instrumentalists were joined by sopranos Dame Emma Kirkby and Elin

Manahan Thomas in Couperin’s captivating Leçons de Ténèbres, extremely

beautiful and genuinely spiritual music for ecclesiastical use. Couperin’s

interest in the Italian style, as represented by Carissimi and Charpentier,

influenced his sacred vocal music, particularly his motets, versets and leçons

de ténèbres, and the result of this stylistic diffusion is enchantingly

presented in the Leçons.

In the Tenebrae service, psalms are sung, interspersed with the

text from the Lamentations of Jeremiah. In Couperin’s setting we

are aware of delicate and deliberate crafting: each of the responsaries is

preceded by a huge musical ‘capital letter’ much like the way the

first letter of a Hebrew psalm is set to a long melisma – as Langham

Smith describes “a musical equivalent to an ornamented manuscript with

elaborately gilded capital letters.”

The two soloists brought their own strengths to the delivery of the text.

Thomas, alert and energised, using the voice to thrill and excite; Kirkby

effortlessly shaped individual phrases into affecting larger units, creating

heart-rending melodic shapes and inflecting the text with human sentiment.

Soaring melodic arches and effortlessly gilded ornaments evoked cathedral

realms. For Kirkby aficionados, vocal purity and beauty is taken for granted,

but she also exhibited a real sense of the architectural splendour of these

pieces.

Thomas’s pronunciation of the Latin text was idiomatically French in

inflection, as it would have been performed at the time. Her ornamentation was

superb; she produced a shimmering beauty which invigorated the sacred text with

exotic nuance. In the third lesson, the intertwined soaring voices evoked

aspiring gothic cathedral arches. The accompaniment was flexible and alert,

sensitive to nuance and creating a real sense of intimacy. The repeated

refrain, “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, convertere ad Dominium Deum tuum”,

(Jerusalem, return thee to the Lord, thy God) both united the various lessons,

and provided variety and gradation.

These are pieces of heavenly exquisiteness, designed to inspire piety

through their sheer beauty. Whatever one’s religious allegiances and

affiliations, this recital inspired ‘devotion’ through the

performers’ absolute commitment to magnificent splendour and nuanced,

expressive inflection, perfectly assimilating the sacred and the secular.

Claire Seymour