There’s purity and Godliness

too — all overlapping and jammed together so intensely into your eyes and

ears, that when the curtain comes down you can be left gasping.

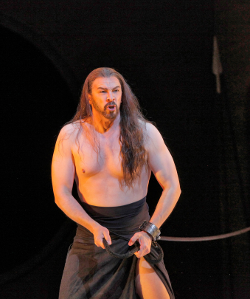

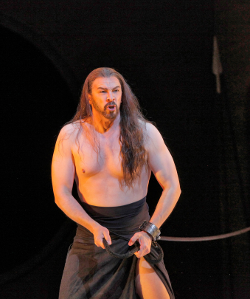

Greer Grimsley as Jochanaan (John the Baptist)

Greer Grimsley as Jochanaan (John the Baptist)

Salome is a spoiled young Princess, the daughter of Herodias and

step-daughter of Herod. Upon hearing the voice of the imprisoned John the

Baptist (here called Jochanaan), she tempts Narraboth, a young soldier who

loves her, to release him. Obsessed with Jochanaan, she is furious when he

refuses to look at her, unmoved when Narraboth kills himself. As her reward

for dancing for Herod she insists on having Jochanaan’s head. The

extraordinary concluding scene of the opera begins as Salome waits fretfully

for the prophet’s head to be brought to her, and ends in an insane frenzy

when she kisses the prophet’s mouth, and Herod screams to his soldiers,

“Kill that woman.”

Gustave Flaubert created an equally John-obsessed Salome in his story

Herodias which formed the basis for Jules Massenet’s opera

Herodiade. There’s no doubt Wilde knew Flaubert’s story. He wrote

Salome in French in 1891 while living in Paris. An English translation

(which Wilde disliked) was prepared by Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde’s 20-year

old lover, in the hope of staging the play in London with Sarah Bernhardt.

Alas, British censors forbade the presentation of biblical characters on stage.

Germany, however, was not so strait-laced. The play in a German translation by

Hedwig Lachman so transfixed Richard Strauss that he began working on it

immediately.

Lise Lindstrom as Salome and Allan Glassman as Herod

Lise Lindstrom as Salome and Allan Glassman as Herod

The opera’s first performance took place in Dresden, Germany in

December 1905. Austria took more time. The Viennese court opera refused to

produce the work, but the directors of the small opera house in Graz, assured

that this “ultra-dissonant biblical spectacle, based on a play by a British

degenerate whose name was not mentioned in polite company,” would produce a

succès de scandale, agreed to the presentation. Its performance on

May 16, 1906 proved a huge social and musical occasion. Strauss conducted.

Giacomo Puccini, Gustav and Anna Mahler, Arnold Schoenberg, Alexander Zemlinsky

and Alban Berg were among the composers present. The work was an instant

success.

San Diego Opera’s production of Salome began life as a joint

venture of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, San Francisco Opera and L’Opéra de

Montréal. First performed in 2009, it was created and directed by

choreographer Seán Curran with lighting and costumes by Bruno Schwengl.

The success of this difficult work depends largely on the talent and stamina

of a soprano who looks like a teen age virgin, and who can sing over a huge

brass-heavy orchestra as easily as that other operatic virgin, Brunhilde.

Strauss’ original orchestra called for a hundred and twelve musicians and

included the newly invented Heckelphone, plus a harmonium and organ (both off

stage). He eventually reduced the orchestra size. Even so, San Diego squeezed

seventy musicians into its pit. Happily, its all star vocal cast met the

challenges of their roles.

Irina Mishura as Herodias and Lise Lindstrom as Salome

Irina Mishura as Herodias and Lise Lindstrom as Salome

Lise Lindstrom’s soprano with its tender vibrato in middle voice, blossoms

to silvery at the top with an edge that at once youthful and strong enough to

ride the orchestral waves. Fiddling with her long hair and biting her nails,

she gave a convincing portrayal of a spoiled young princess, was admirably

feline in her pursuit of Jochanaan, and graceful in the not very voluptuous

dance created by Curran. Bass-baritone Greer Grimsely was a resounding

Jochanaan, clearly tempted by the young girl, and convincing as he tried vainly

to move her to compassion. Mezzo soprano Irina Mishura’s Herodias, though

well sung, was not a commanding presence. Someone should have told her not to

wave her wrists around like a hapless housewife. Neither she, nor Allan

Glassman, who sang gloriously as Herod, seemed like people capable of running

an empire. I can only assume it was the direction that turned them into a pair

of restless, ditzy characters. Tenor Sean Panikkar was compelling as the

enraptured Narraboth.

Despite the excellent voices, sadly I was not as out breath as I would like

to have been when the curtain descended. Part, I think can be attributed to the

staging of the last moment of the opera in which Salome is on her feet, as

though considering her deed, rather than being fully immersed in the horrid act

that Herod is seeing and that the orchestra is describing. Steuart Bedford’s

conducting too, often lost focus on the emotions that this hideous tale should

evoke. The simplest example perhaps relates to the moments during which Salome

is waiting for Jochanaan’s head — waiting to hear his scream, waiting for

his body to fall. The only music Strauss gives us at first are B flats ticking

unevenly in the bass.

The notes and intermittent silences, followed by the subsequent undulating

comments of the woodwinds should have been chilling enough to make my skin

crawl. They weren’t. Even at its screeching heights the orchestra often

lacked tension and energy.

Lise Lindstrom as Salome

Lise Lindstrom as Salome

I am never happy to see a Salome without a moon. Wilde told

Bernhardt that the moon had a leading part in the play. Directors who ignore

the moon, ignore the poetry and imagery of the play. There are thirty-two

mentions of “moon” in Wilde’s play, fifteen of “mond” in the

libretto. A page described the moon the moment the curtain rises. “How

strange the moon seems. She is like a woman rising from a tomb.” To which

Narraboth responds, “a little princess who wears a yellow veil, and whose

feet are of silver.” The moon’s appearances and disappearances move in

relation to Salome’s actions. But there’s another reason I particularly

missed the moon. The first musical note Strauss made on his copy of the

Salome libretto was to set Salome’s key as C# minor, the key of the

Moonlight Sonata. (Please don’t write to me, I know Beethoven didn’t give

the sonata that name. But it had that name in Strauss’ time).

Finally, I’m also unhappy with Salomes in which only the five

Jews are dressed in 21st century clothes with specifically identifiable Jewish

religious accouterments. It’s both a stereotype and a cliché. A director who

can do without a moon in Salome, can surely do without business suit and prayer

shawls.

Estelle Gilson