20 Jan 2015

Yevgeny Onegin in Warsaw

Mariusz Treliński’s staging of Tchaikovsky’s operatic masterpiece is visually fascinating but psychologically confusing

Mariusz Treliński’s staging of Tchaikovsky’s operatic masterpiece is visually fascinating but psychologically confusing

For some strange reason Tchaikovsky’s Yevgeny Onegin has recently been subject to the same directional quirks and aberrations that used to be reserved almost exclusively for the works of Wagner. Carrying on the bad old traditions of German directors such as Harry Kupfer and Hans Neunenfels, most of the recent culprits seem to have sprung from Poland. There was Michał Znaniecki’s aquatic staging in Bilbao and Zagreb; Krzysztow Warlikowski’s ‘Brokeback Mountain’ Yev-gay-ny in Munich (which certainly outraged the good Catholic burghers of Bayern) and pre-dating them all, Mariusz Treliński’s visually exciting but seriously flawed interpretation for the Polish National Opera in Warsaw in co-production with the Palacio de las Artes Reina Sofía in Valencia.

Mr Treliński’s most obvious and definitely annoying directional digression was the introduction of a non-speaking, omnipresent, white-clad, walking-stick-wielding spectral character listed in the programme as ‘O***’ (definitely not ‘O’ for Onassis). This repellent, diabolical, bald-headed ogre seemed at times to be a benign version of an old Onegin as a passive observer of past events (similar to Kasper Holten’s recent concept for Covent Garden) and at others, a truly Mephistophelian figure stage-managing every detail of the drama with absolute and brutal malevolence. Mariusz Treliński is a celebrated Polish film director and now Artistic Director of the Polish National Opera. Somehow he seems to see no problem in the ambiguity of the soi disant ‘superfluous man’ character as both passive observer and aggressive avatar puppeteer. At the opening of Act 2 O*** wears a large Anubis-like face mask and forces Tatyana to put on a black blindfold before leading her to the ball. Portents of death abound, either psychological or corporeal. He then puts the same blindfold on Lenski and dances with him too — clear inspiration for Krzysztow Warlikowski and the ‘Brokeback Mountain’ Onegin boys in Munich. O*** is positively vulture-like when he thrusts a sheet of paper at Tatyana in the Letter Scene and terrorizes her into completing the missive. Her important psychological state of nervous introspection, adolescent insecurity and romantic impetuosity are completely subsumed by this gratuitous distraction.

Irina Mataeva as Tatyana

Irina Mataeva as Tatyana

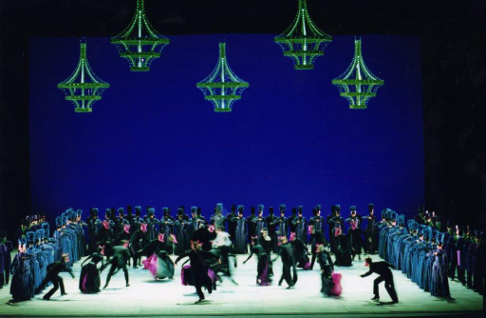

On the other hand, if ever there was an obvious corporate sponsorship nexus between an opera production and a famous logo, it was Treliński’s apple-laden images. Steve Jobs would have loved it. While Andrea Breth converted the Salzburg stage into a giant wheat field and Robert Carsen turned the Metropolitan’s mis-en-scène into a carpet of dead leaves, in this Polish version we had apples, apples, and more apples. A huge apple tree silhouette dominates the rear of he stage; an enormous pile of apples covers a refectory table in the first scene when Madame Larina and Filipjevna are supposed to be making jam (apple sauce?); O*** picks up an apple in the very first bars of the score; Onegin aggressively munches one and at the conclusion of the opera, a veritable harvest of (rotten?) apples roll towards the front of the stage. The autumnal demise of Onegin’s character with Granny Smith symbolism. The installation of a catwalk around the orchestra pit brought a lot of the drama very close to the audience but also created a certain cheap Victorian music-hall effect. Robert Carsen used the same idea in a recent production of Die Zauberflöte in Baden-Baden but Schikaneder and Mozartian Singspiel and are a very different box of apples to Aleksandr Pushkin and Tchaikovsky. Outstanding lighting by Felice Ross created several superb visual images of Boris Kudlićka’s staging, such as Tatyana laying prostrate in the shadows of bleak white birch trees at the end of Act I Sc.1. As a Pole creating a production for a Polish staging, it was also rather brave of Mr Treliński to have Emil Weslowski’s choreography of the Act III Polonaise as a series of incredibly slow stylized robotic steps rather than the usual swirling energy of such a powerful dance. It seemed to work. A sense of fatalistic inevitability predominates this staging, with or without O***, and is certainly appropriate to Aleksandr Pushkin’s characterizations or indeed early 19th century country life in Russia in general.

The singing was for the most part more than satisfactory. In the title role, Polish baritone Artur Ruciński was vocally impressive and dramatically credible even if the cold, contemptuous arrogance of Peter Mattei in Salzburg or Dmitri Hvorostovsky at the Met was absent. This meant his emotional collapse in Act III when finally rejected by Tatyana was demonstrably less empathetic, although his anguish was certainly very well acted — so much so that the audience broke into applause before the opera had actually ended. Although the voice was occasionally a little fuzzy, slightly pushed and sometimes lacking in clear focus, his Act I Когда бы жизнь домашним кругом aria was mellifluously sung and displayed a fine legato and agreeable rich timbre, especially in the upper-middle register. In opting for the concluding high F on мечты нежней,he sang it forte instead of piano as indicated in the score, but a solid ringing top is clearly one of Mr Ruciński’s strongest vocal attributes.Irina Mataeva’s interpretation of Tatyana had an Ophelia-ish quality about it which verged on the wide-eyed mystical if not slightly demented, especially in the first two acts. There were some intonation problems in the upper register and a rather intrusive wide vibrato which contradicted the innocence and youth of the character so well captured by Tatyanas such as Ileana Cotrubuş in the past or Anna Samuil in more recent productions. While the Act I Letter Scene was seriously marred by the distracting intrusion of O*** who alternated between a cruel, homicidal stalker and a tender Onegin with the speed of a Rossinian hemidemisemiquaver (guardian angel or wily temptor?) Miss Mataeva’s top Bbs were not particularly clean and the final Ab on вверяю! waspushed and not very pleasant.

Ballroom Scene, Act II

Ballroom Scene, Act II

Preening across the stage in Act III in a Schiaparelli pink cocktail frock, she looked like Audrey Hepburn in ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’ — complete with cigarette holder. Fortunately by the second scene her singing of Онегин! Я тогда моложе had a much improved vocal assurance and the lower tessitura seemed more comfortable, not withstanding the persistent vibrato. Even the final powerful fff B natural on проща! was well taken.Despite showing surprising sexuality with Lensky, the Olga of Karolina Sikora, was dramatically rather bland, vocally underpowered and burdened with an unattractive wobble. Ewa Marciniec’s Larina was the same without the vibrato — or the sex. As Lensky, Ukrainian tenor du jour sensation Pavlo Tolstoy sang with restrained elegance, a warm forward dulcet timbre and excellent Alfredo Krause-like phrasing. His Я люблю вас люблю вас Ольга ardent outburst to Olga in Act I was passionate without being vulgar; the beginning of the Act II Sc.1 finale ensembleВашем доме! had a really beautiful tender mezza-voce cantilena andKuda,kuda in Act II was movingly sung without being saccharine. His upper register, especially on the top Ab in the ff andante mosso change on Желанный друг was perfectly focused and the whole scena was commendable for consistently fine intonation and bright, Italianate vocal colouring. Of the smaller roles, the Triquet of Tomasz Piluchowski was vocally undistinguished and had serious tempo coordination problems with the orchestra in his Act II encomium to Tatyana. Anna Lubanska’s Filipjevna was a real delight. Possessing a Regina Resnik-esque rich, plummy lower register and deep chest notes, she was also dramatically an ideal incarnation of the devoted babushka. As Prince Gremin, Aleksander Teliga lacked stage presence but made up for it with fine, well-articulated singing and an outstanding lower register. The final low Gb’s at счастье had impressive strength and projection.

The orchestra was capably led by Andriy Yurkevych. There was some fine string playing (e.g. the cello opening to Act II Sc.2 and the introduction to Kuda kuda); excellent brass (eg. the piano horn solo quaver phrases beginning at measure 187 in Tatyana’s Letter Scene); delicately balanced winds (especially the cheeky scale passage exchange between flute, oboe and clarinet in Act I at measure 152 and during the echoed major fifth piano quavers between flute, clarinet (and horn) beginning at the andante change at measure 47 in Tatyana’s Letter scene. There was also some very sensitive clarinet solos in Kuda, kuda. Unfortunately it seemed that maestro Yurkevych was a little too concerned with not overpowering the singers in this huge theatre, which should not have been a concern. When freed from such constraints, such as in the ff orchestral tutti at bars 270-293 of Tatyana’s Letter scene and the Act III opening Polonaise, the orchestra played with powerful precision and commendable attention to the markings of the score.

It will be interesting to see how Mr Treliński’s forthcoming unusual double-bill of Iolanta and Bluebeard’s Castle (the first co-production between the Polish National Opera and the Metropolitan Opera in New York) will be received by operatically conservative Manhattanites. Hopefully the Polish pippins will not be too bruised by the real Big Apple.

Jonathan Sutherland

Cast and production information:

Larina: Ewa Marciniec, Tatyana: Irina Mataeva, Olga: Karolina Sikora, Filipjevna: Anna Lubańska, Yevgeny Onegin: Artur Ruciński, Lensky: Pavlo Tolstoy, Prince Gremin: Aleksander Teliga, Triquet: Tomasz Piluchowski, O***: Emil Wesołowski. Conductor: Andriy Yurkevch, Director: Mariusz Treliński, Set Design: Boris Kudliča, Costumes: Joanna Klimas, Lighting: Felice Ross, Choreography: Emil Wesołowski. Polish National Opera, Teatr Wielki, Warsaw, 11th January 2015.