There was nothing dull about Dame Edith Sitwell, who was described in her dotage by Virginia Woolf as resembling an ivory elephant: ‘Majestic, monumental …

an old empress’. And, no one could ever accuse the flamboyantly idiosyncratic, unabashedly elitist Sitwell of having followed the crowd. Indeed, being

ekkentros - off-centre - seems to have been at first a refuge from her indifferent parents’ cold neglect and finally almost her

raison d’être. Sitwell’s 1930 cultural biography,

English Eccentrics - a cabinet of human curiosities - was thus a perfect marriage of

author and subject.

But, with its elaborate prose, repetitive random meandering, and a sprawling character-list of aristos, quacks, hermits and dandies, English Eccentrics might not seem ideal material for an opera libretto. Fortunately, Australian composer Malcolm Williamson and his librettist

Geoffrey Dunn thought otherwise, when Williamson was commissioned to write an opera for the 1964 Aldeburgh Festival following the success of his operatic

adaptation of Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana at Sadler’s Wells the previous year. Dunn constructed a sketch-book of seventeen short scenes

through which forty or so wild and wacky famous eccentrics parade: aristocrats, tradesmen, vicars, policeman and servants.

Kieran Rayner (Lord Rokeby) with William Thomas and Steven Swindells. Photo Credit: Clive Barda/ArenaPAL.

Kieran Rayner (Lord Rokeby) with William Thomas and Steven Swindells. Photo Credit: Clive Barda/ArenaPAL.

We meet real-life historical figures such as the amphibious Lord Rokeby - who, after a visit to a French spa became addicted to bathing and subsequently

spent his life in the bath; and, the hot-tempered Captain Thicknesse, who bequeathed his right hand, to be cut off after his death, to his son Lord Audley.

Then, there’s Old Tom Parr who, when he died in 1635 purported to be 152 years-of-age. And, the ‘celebrated’ amateur thespian Robert, or Romeo, Coates,

famous in his day as the world’s worst actor and whose assaults on Shakespearean Tragedy caused such uproar and hilarity that one group of theatre-goers

had to be carried into the open air to receive medical attention.

The characters in this gallery of extremes are barking mad and their stories bizarre - and also entirely unconnected. So, the opera has no ‘plot’. Rather,

it’s a melange of mad escapades which tumble into each other with gleeful irrationality. Paradoxically, this formal ‘chaos’ proves advantageous to

Williamson - who settled permanently in England and became the first non-Brit to be appointed Master of the Queen’s Music. The composer’s eclectic score

proves that he was a master, too, of pastiche and parody, and could turn his hand to any musical idiom, effortlessly slipping from jig to hymn-tune, via

ragtime, rumba, Mozart and music hall ballad at the flick of a baton. Indeed, it’s the juxtaposition of incompatibles, both on stage and in the score - and

their occasional unexpected, improbable reconciliation and resolution - that gives the opera its delicious piquancy.

British Youth Opera at the Peacock Theatre. Photo Credit: Bill Knight.

British Youth Opera at the Peacock Theatre. Photo Credit: Bill Knight.

Williamson’s deftness and pithiness clearly inspired the design team of this fantastic British Youth Opera production who, with the aid of two stage-height

silk drapes that slid fluidly across the stage, swished us from scene to scene with such easy grace that we barely noticed that it was almost impossible to

work out exactly what was going on!

The individual stories are compressed and we whirled through them at break-beck pace. Director Stuart Barker’s direction was fittingly economical and full

of wit. Barker and his movement director, Victoria Newlyn, drew absolutely superb performances from the 4-strong chorus and a cast of 6 soloists each of

whom is required to personify a medley of eccentrics. They relished the outsized oddities of their characters, and jumped in and out of Laura Jane

Stanfield’s terrifically outlandish period costumes with impressive alacrity.

The singers enjoyed Williamson’s medley of melodies, too, though this is not easy music to sing. Williamson may have had a sure touch in terms of how to

accompany voices, using spare instrumental textures and ambience-defining repetitive motifs, but the vocal lines themselves are often demandingly angular

and unpredictable. The results here were mixed but unfailingly committed.

Soprano Iúnó Connolly delivered strongly characterised and technically assured performances as Sarah Whitehead, the woman whose brother was hanged for

forgery leaving her in penury, and Princess Caraboo, a West-Country maid who has delusions of grandeur.

Matthew Buswell (Captain Philip Thicknesse) with Maria McGrann, William Thomas, Sîan Griffiths and Steven Swindells. Photo Credit: Clive Barda/ArenaPAL.

Matthew Buswell (Captain Philip Thicknesse) with Maria McGrann, William Thomas, Sîan Griffiths and Steven Swindells. Photo Credit: Clive Barda/ArenaPAL.

Baritone Matthew Buswell demonstrated his dramatic nous and range as the nymphomaniac centenarian Tom Parr, desperate to wed and bed the Countess of

Desmond (Polly Leech), and the rambunctious Captain Philip Thicknesse, an ‘ornamental hermit’ who struggles to pen his memoirs as his memory wanes. Buswell

sang with finely pitched and focused tone and stood out for the clarity of his diction.

William Thomas, Steven Swindells, Maria McGrann and Sîan Griffiths with David Horton (Romeo Coates). Photo Credit: Bill Knight.

William Thomas, Steven Swindells, Maria McGrann and Sîan Griffiths with David Horton (Romeo Coates). Photo Credit: Bill Knight.

As that prince of popinjays, Romeo Coates, tenor David Horton cut a fine figure in his gold-buttoned, jewel-encrusted garb topped with a fantastical

Regency wig and exhibited theatrical prowess worthy of his character’s delusions. Maria McGrann, Siân Griffiths, Steven Swindells and William Thomas formed

a vivacious choral quartet, linking the scenes and commentating on the action with persuasive fluency.

Conductor Peter Robinson swept things briskly along and drew vibrant, sharply defined playing from the seven instrumentalists from the Southbank Sinfonia.

The sparseness of Williamson’s orchestration should have been of benefit to the singers but too often the diction was muffled and the singers were not

helped by the Peacock Theatre acoustic - given the inherent incomprehensibility of the opera, surely there was a strong case for surtitles.

Sitwell, stand-offish and snooty, declared that eccentricity ‘exists particularly in the English, and partly, I think, because of that peculiar and

satisfactory knowledge of infallibility that is the hallmark and birth-right of the British nation.’ But, she herself, was in fact far from

indifferent to public criticism and her aloof façade hid her intense hypersensitivity. Her Eccentrics are a similarly conflicted bunch: there is a

coolness to the wit and an underlying sadness as they retreat from reality into the lonely refuge of idiosyncrasy.

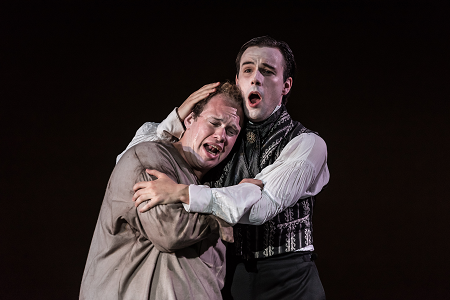

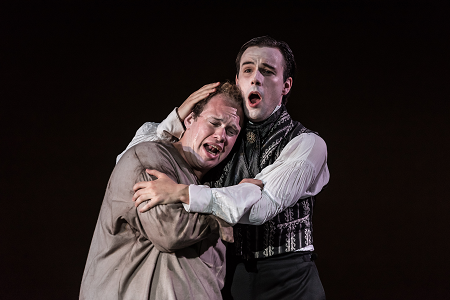

Edward Hughes (Beau Brummell) and Kieran Rayner (Etienne). Photo Credit: Clive Barda/ArenaPAL.

Edward Hughes (Beau Brummell) and Kieran Rayner (Etienne). Photo Credit: Clive Barda/ArenaPAL.

And, Barker recognised and communicated the way grotesqueness and grief sit side-by-side. The Eccentrics were lampooned but also portrayed with sympathy

and sadness. In the closing moments, Edward Hughes’s Beau Brummell cut a figure of real pathos as his was carted off to the madhouse to the accompaniment

of a poignant nuns’ duet (Connolly and Leech), and the ‘big tune’ chorus that followed showed that Williamson would have given Andrew Lloyd Webber a run

for his money.

Following a strikingly direct and dramatically consistent production of Owen Wingrave a few days before, this rollicking revue confirmed British

Youth Orchestra’s creative confidence and an absolute commitment to those works that languish in the operatic margins. The short-list of potential

repertoire for the 2017 season includes Judith Weir’s The Vanishing Bridegroom, Mozart’s Don Giovanni and La finta giardiniera, but whatever the final programme one can guarantee that the operas chosen will be presented with an assurance and

individuality of which Sitwell would have approved.

Claire Seymour

Malcolm Williamson: English Eccentrics

Iúnó Connolly (Miss Tylney-Lond, Miss Beswick, Mrs Dards, Sarah Whitehead, The Duchess of Devonshire, Princess Caraboo, First Nun); Polly Leech (The

Countess of Desmond, Lady Lewson, Miss FitzHenry, Mrs Birch, Lady Jersey, Mrs Worrall, Second Nun); David Horton (The Rev Mr Jones, Robert (Romeo) Coates,

A Clerk at the Bank, Dr Graham, The Vicar of Almondsbury, Mr Clanronald MacDonald); Edward Hughes (Lord Petersham, John Ward of Hackney, Young Whitehead,

Beau Brummell, Dr Wilkinson); Kieran Rayner (Dr Katterfelto, Lord Rokeby, Alderman Birch, Lord Rothschild, Mr Worrall, Etienne), Matthew Buswell (Thomas

Parr, Major Peter Labellière, The Prompter, Governor of the Bank of England, Roberts the Forger, Dr Dalmahoy, Captain Philip Thickness, Parish Constable).

Maria McGann (Quartet Soprano), Siân Griffiths (Quartet Mezzo-soprano), Steven Swindells (Quartet Tenor), William Thomas (Quartet Bass).

Southbank Sinfonia: Scott Lowry (violin), Zoé Saubat (cello), Jordi Juan Perez (clarinet), Bartosz Kwasecki (bassoon), Etty wake (trumpet), Tom Lee

(percussion), Joe Howson (piano).

Director, Stuart Barker; Conductor, Peter Robinson; Set designer, James Cotterill; Costume designer, Laura Jane Stanfield; Movement director, Victoria

Newlyn; Lighting Designer, David Howe.