Or as Jones puts it, ‘the place where “not funny” meets “funny”’. But, Tarantino is always on the side of the underclass, whereas Jones does not encourage

us to care about or understand any of Handel’s characters. We are desensitised to the blood-letting within minutes. Moreover, there is a complete

disjunction between the elegance of Handel’s musical rhetoric and the crude carnage that unfolds, often disruptively and incongruously, on stage.

The first night audience at Wilton’s loved it. To declare that musico-dramatic values have not been upheld - that one doesn’t like Handelian eloquence

being smashed into smithereens by stomping boots, bludgeoning hammer blows and psychiatric frenzies - probably puts one in the ‘reactionary’ camp.

But, what is a shame about Jones’ production is that it does not serve its purpose; or, to put it another way, those whom it is designed to ‘serve’, have

to work hard to overcome its limitations. For this production is intended to showcase the talents of Jones’ fellow Jette Parker Young Artists and it’s to

the credit of the young cast that their Handelian credentials out-shine the shock factor shenanigans.

Oreste was one of five works produced by Handel in 1734 for his first season at the recently opened Royal Opera House. He had a busy season: one that

resulted in newly composed works such as Ariodante and Alcina. So, perhaps it wasn’t surprising that when Oreste opened on 18 December 1734 there was a considerable

amount of operatic re-cycling on parade.

Photo credit: ROH, Clive Barda.

Photo credit: ROH, Clive Barda.

Oreste was the first of the three pasticcio operas that Handel himself created from his own works. He borrowed the overture and the forty other numbers

from various of his operas, adding only a few new secco and accompagnato

recitatives and two ballet movements (the dance sequences were included for Marie Sallé and her company, who appeared in all Handel’s productions in his

first Covent Garden season of 1734-5); and, he altered the orchestration and key of particular numbers as dramatically and musically required.

Handel aficionados might find it disconcerting to hear a character in one drama sing an aria recognised from a different musico-dramatic context, but while

musicologists might quibble over such identifications (one scholar suggests that extracts from some thirteen operas written between 1713 and 1733 were

recycled), the audience in the theatre is concerned only with dramatic effectiveness. And, if Handel did not have time to compose new music, that doesn’t

mean that he recklessly didn’t give due thought to the sequence and shape of the musical drama. Oreste is skilfully wrought, allowing that there is cliché

and humdrum-ness alongside musical gems.

Adapted, with additional characters interpolated, from an earlier libretto by Gualberto Barlocci, the story is based on the Iphigenia myth, as treated by

Euripides, combined with elements borrowed from Sophocles and Aeschylus. We’re in familiar dysfunctional family territory. Oreste, consumed by madness

after he has murdered his mother Clytemnestra, lands in Tauria having been guided by an oracle. Ifigenia, though not recognising her sibling, is prompted

to save him from sacrifice, and is aided by an admirer, Toante’s captain Filotete. Oreste’s wife Ermione and his friend Pilade come in search of him, and

are arrested and condemned to death. After much threat of sacrifice and self-sacrifice, Ifigenia reveals herself as Oreste’s sister and with Filotete’s

help inspires the Taurians to overthrow Toante and restore peace.

In Jones’ hands Ifigenia - miraculously saved from sacrifice at Aulis - has a new role: less high priestess of Diana, and more henchman of King Toante, she

has to murder all strangers to the land of the Taurians. Wilton’s is in the East End, so Jones, predictably and uninspiringly, opts for grunge and graffiti

and adds a bucket-load of gratuitous gruesomeness. The action is contained within a tag-strewn cube: designer Matt Carter signals that what we are about to

see will be ‘Raw!’ Jones believes that ‘scenery is the enemy of directors’: one couldn’t help thinking that the exposed brickwork of Wilton’s itself might

have been more effective. There are few props: just a radiator, a box of flex wire and other torture tools, a filthy yellow wheelie bin, a glowing electric

fly-zapper, a shabby standard lamp.

With a plastic apron and gloves to safe-guard her knee-length ti-shirt, a panda-eyed Ifigenia strays in clutching a hammer and, wearily

passing through a door at the rear of the cube, enters an execution chamber and proceeds to get on with the business in hand. To the accompaniment of

Handel’s eloquent overture, an anonymous victim is bludgeoned and blood splatters the glass window. And so it goes on. Stomping about in combat fatigues

and dark glasses, Toante is a Mugabe-like megalomaniac whose raving becomes ever more demented as the body count rises. Dressed in an orange body suit and

Doc Martens, Filotete is a willing accomplice in butchery, slavering rabidly as he stuffs another limb in a bin-bag. The two strangers from Argos wash up

in this nightmarish slaughter chamber like a pair of ragged refugees and are sucked into the amorality; at the close, the hammer-wielding Ermione leads the

way in the mutual massacring of Toante.

Jennifer Davis as Ifigenia. Photo credit: ROH, Clive Barda.

Jennifer Davis as Ifigenia. Photo credit: ROH, Clive Barda.

Reading Jones’ explication in the programme booklet, one is disheartened by the absence of words such as ‘Handel’, ‘music’, and by the summative rationale:

‘I think the behaviour of all the characters is pretty bad … I think the behaviour is awful. All these people are awful. That is the starting point.’ He

sees his job as ensuring ‘the behaviour you see on stage sustains the story … and is as real as possible against the unreality of the music’. But,

fortunately, as Jones notes, ‘musically the piece will sustain itself’ - the problem is, can he sustain our interest during three long acts of

ultra-violence which is divorced from the musical narrative?

The young cast showed that they know how to shape a Handel aria, how to negotiate ornament, and how to use vocal colour to characterise and communicate.

They worked hard, and with some terrific musical results.

Angela Simkin’s pyjama-clad Oreste is a wide-eyed, twitching self-harmer, but she sang with impressive, quiet concentration and revealed a glowing vocal

polish. As Ifigenia, Jennifer Davis showed that at the top she can manipulate colour, dynamic and weight of her lyric soprano with ease, and that she can

embellish stylishly. Vlada Borovko was in powerful voice as Ermione; the duet of farewell (taken from Floridante) for Oreste and Ermione which closes Act 2

was a rare heart-warming moment amid the cold callousness.

Angela Simkin as Oreste. Photo credit: ROH, Clive Barda.

Angela Simkin as Oreste. Photo credit: ROH, Clive Barda.

As Pilade, tenor Thomas Atkin helped, momentarily, to alleviate the relentless ferociousness of the proceedings, singing with quiet beauty in his Act Two

aria of adoration for his beloved Oreste; he managed Handel’s high-lying lines well and shaped the phrases gracefully.

Simon Shibambo has a resonant bass baritone that, in another production, could command great authority: here, he used his voice well, just about overcoming

the distraction of Toante’s ridiculous crazed rampaging. The latter may have been the cause, too, of Shibambo’s tendency to lose touch with the band. As

his over-zealous aide, Filotete, Gyula Nagy revealed a strong baritone but needed a bit more variety of volume and shade.

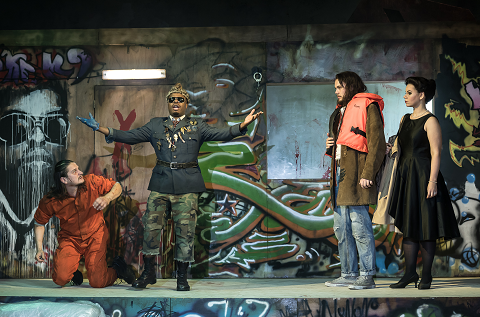

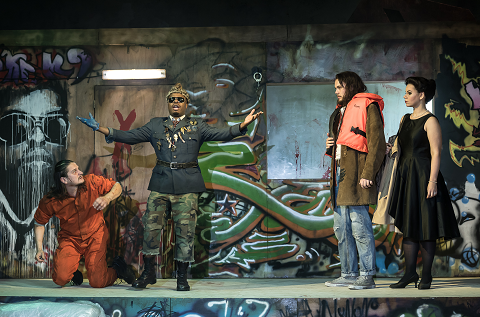

Gyula Nagy as Filotete, Simon Shibambu as Toante, Thomas Atkins as Pilade, Vlada Borovko as Ermione. Photo credit: ROH, Clive Barda.

Gyula Nagy as Filotete, Simon Shibambu as Toante, Thomas Atkins as Pilade, Vlada Borovko as Ermione. Photo credit: ROH, Clive Barda.

One might have wondered why members of the Southbank Sinfonia, not known for adventures in ‘authenticity’, had been chosen as accompanists, but in the

event they played superbly, led by conductor James Hendry who seemed to have every detail of the score at his command. The violin lines had real character

and were thoughtfully shaped and ornamented; the bass was strongly driven. Harpsichordist Nick Fletcher, seated on the opposite side of the theatre to the

rest of the band, offered some imaginative continuo flourishes.

Jones ends not with redemption and reconciliation but with existential dissolution. It’s all too much for Atkin’s Pilade: his lovely final aria having been

overshadowed by the orgiastic clubbing of Toante, Pilade dons an orange life-jacket and, presumably, swims off in search of fairer lands. At the end of

this merciless blood-feast, I knew how he felt.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Oreste

Oreste - Angela Simkin, Ifigenia - Jennifer Davis, Filotete - Gyula Nagy, Ermione - Vlada Borovko, Pilade - Thomas Atkins, Toante - Simon Shibambu;

Director - Gerard Jones, Conductor - James Hendry, Designers - Gerard Jones and Matt Carter, Costume Designer - Donna Raphael, Lighting Designer - Mimi

Jordan Sherin, Movement Director - Anjali Mehra, Southbank Sinfonia.

Wilton’s Music Hall, London; Tuesday 8th November 2016.