In the first concert, Christian Thielemann led four soloists and a choir in

Bruckner’s Third Mass with an unexpected light result. Before the

intermission, Gidon Kremer performed In Tempus Praesens, Sofia

Gubaidulina’s second concerto for violin and orchestra. In the Saturday

Late Night concert, Barbara Hannigan joined Simon Rattle and several Berliners

in a sensual performance of Gérard Grisey’s apocalyptical

Quatre chants pour franchir le seuil.

Fascinated, I witnessed the vastly different, but equally persuasive,

styles of Thielemann’s slight aggression in his artistically

authoritarian ways as opposed to Rattle’s inviting and democratically

inclusive approach.

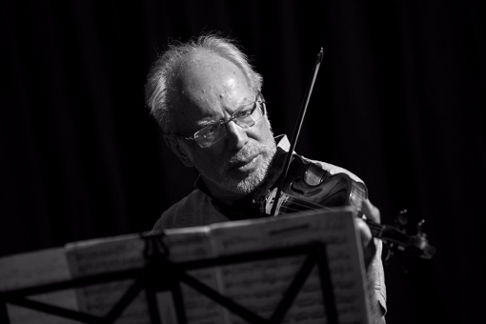

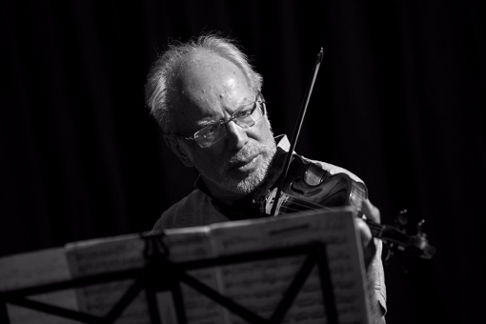

Kremer appeared to have a Herculean task in Gubaidulina’s enchanting

cosmos of extremes. When you see her for the first time, you cannot help but be

surprised by her tiny frame as the vessel for such fiery music. She channels

her coarse, instinctive energy through an uncompromising intellectual curiosity

that makes her compositons sound extreme, yet familiarly approachable.

Gidon Kremer [Photo by Paolo Pellegrin]

Gidon Kremer [Photo by Paolo Pellegrin]

Sophie Ann Mutter and Rattle premiered the work at the Lucerne Festival ten

years ago. Then, it was perceived as a nurturing work, but tonight Kremer

infused it with an inexhaustible rawness emanating from his aged musicality.

Highly dramatic and elaborate, it was not what I expected from the legendary

violinist. In fact, tonight’s rendition would have suited the horrors of

humanity of a Stanley Kubrick film. Absolutely thrilling!

As if his life depended on it, Mr. Kremer turned into a technical wizard on

the violin. The Latvian soloist thrived in Gubaidulina’s states of

frenzy, as he crevassed up and down her icy hot spikes. He had few moments

where he could catch his breath. In an exhilarating crescendo, passion flowed

as Emmanuel Pahud quarrelled with Kremer back and forth on the flute, producing

one of the orchestral highlights of the evening. During the cadenza Kremer

sustained razor sharp focus. He turned his play into a thirty-minute sprint,

rather than a steady marathon.

Containing the violent outbursts from the percussion and the horrifyingly

shrieking edges yelped by the trombones, Thielemann kept clear tempi for

Gubaidulina. His tight control created a serrated edge to the Berliner sound.

In a disorienting novelty, reverberating overtones seemed to dampen each other

creating unusual pockets of deafness.

In Bruckner, Thielemann let himself shine as he disclosed his inner-artistic

exuberance. The Mass No. 3 in F minor for soloists, choir, and organ

was performed with Paul Hawkshaw’s 2005 edition. It includes Robert

Haas’s sonorous organ passages. The brilliance and depth of the Berliner

strings burned in the “Credo” as they repeated their motifs, a

typical building block of Bruckner’s industrialism. Christian Schmitt

guested on the organ, his vibrations grounded the Mass, adding heavy depths

underneath the light tone of the orchestra.

In the beginning, the Bayreuth soprano Anne Schwanewilms seemed to phone in

her performance. She did not hit her stride until the Benedictus, and

ultimately proved her worth and then some with the final verse “dona

nobis pacem”. Michael Schade’s tenor voice sounded sturdy and

decent, but he just did not seem too involved.

On the other hand, Franz-Joseph Selig’s bass charmed with character as

an ameliorating contrast to Schade’s missing. And one must not forget,

Wiebke Lehmkuhl’s alto role! With her tree trunk of a voice, she grounded

Bruckner with an earthy gravitas. When she sang, she became a backbone to the

voices, connecting all the branches, bringing about a determined sense of

cohesion.

Above all, the Rundfunkchor Berlin prepared by Gijs Leenaars, proved vital.

As one breathing organism of Bruckner’s vocal brilliance, this tremendous

choir blew me away. In the Gloria and Credo their voices induced a thrilling

current in Thielemann’s momentum. Fortissimo and pianissimo, these

singers provoked skin crawling effects over my arms throughout the evening.

Now without baton and much more instinctual, Thielemann basked Bruckner in

glory. He conducted with both hands free. While leaning back like a painter

observing his work in progress, his other hand curved slight nuances on his

orchestral canvas. He was clearly more at home in Bruckner than

Gubaidulina.

With all the noise from Bayreuth over Thielemann’s reign, the

conductor came across much less stolid than I had anticipated. Although in his

violently incisive gestures I recognised an authoritarian, I also detected a

surprisingly warm heartedness that effectively permeated through the BPO.

Thielemann elucidated the many virtues of the BPO, especially from the

brilliant brass in the Gloria that might as well have reflected the splendour

at Heaven’s Gate.

David Pinedo