16 Jan 2017

Don Quichotte at Chicago Lyric

A welcome addition to Lyric Opera of Chicago’s roster was its recent production of Jules Massenet’s Don Quichotte.

A welcome addition to Lyric Opera of Chicago’s roster was its recent production of Jules Massenet’s Don Quichotte.

The lead was portrayed definitively by Ferruccio Furlanetto; in the roles of Dulcinée and Sancho, Clémentine Margaine and Nicola Alaimo, both featured in their debuts with the company, made equally strong impressions. Additional courtiers and rival suitors for the affections of Dulcinée — Pedro, Garcias, Rodriguez, and Juan — were portrayed by Diana Newman, Lindsay Metzger, Jonathan Johnson, and Alec Carlson. The roles of servants were sung by Takaoki Onishi and Emmett O’Hanlon, while the chief of the bandits was Bradley Smoak. This production from San Diego Opera was directed at Lyric Opera of Chicago by Matthew Ozawa with sets and costumes by Ralph Funicello and Missy West; the lighting designer was Chris Maravich. The Lyric Opera Orchestra was conducted by Sir Andrew Davis, and the Lyric Opera Chorus was directed by its Chorus Master Michael Black.

At the start of each act throughout this production a quote from Cervantes’ Don Quijote appears on a scrim as a generalized introduction to the action about to unfold. Since the source for Massenet’s librettist Henri Cain was a 1904 stage play by Jacques Le Lorrain, taking inspiration from Cervantes, these citations help to return the operatic material to its ultimate novelistic origins. The first of these quotes, shown during the overture, describes the protagonist being “captive of Dulcinée, ” based on a passage from part I of Cervantes’ text. A child, seated on the stage and holding a book while reading, is also now seen just before the start of the action as a further reminder of the work’s origins in literature. The first scene approximates a Spanish courtyard while protagonists and chorus wear costumes with touches of late Renaissance style. Before Dulcnée can step onto her balcony overlooking the courtyard, the chorus cries our “Alza!” and “Vivat Dulcinée!” as a prelude to the four suitors singing of their desire to see her. As if in response to these entreaties Dulcinée appears and takes up the cry “Alza!” in her opening aria, “Quand la femme a vingt ans” [“When a woman is twenty years of age”]. Ms. Margaine performs an elaborate melisma on this word before launching into her thoughts on a young woman’s emotional needs and risks. Margaine’s warm, flexible mezzo voice sings comfortably in Dulcinée’s range, her embellishments adding to the tantalizing appeal of the character.

Nicola Alaimo and Ferruccio Furlanetto

Nicola Alaimo and Ferruccio Furlanetto

The subsequent exchange between rival suitors features Mr. Johnson’s ironically heartfelt intonation on “mon pauvre ami!” [“my poor friend!”] as his character Rodriguez chides the declarations of a lovesick Juan. This banter is interrupted when the suitors and the crowd together proclaim Quichotte’s entrance with his squire. Messrs. Furlanetto and Alaimo proceed into the courtyard on stuffed animals with Quichotte dressed in the stylized formality of a traveling knight. After admonishing the squire Sancho to be generous to the young and the poor, calling them angels, the “Chevalier” retreats to gaze up at the balcony of Dulcinée. Furlanetto’s movements and declamation reveal here a true assumption of character, while he musters the energy of an aging knight to fulfill the timeless ideals of chivalry. The serenade performed for the adored Dulcinée, “Quand apparaissent les étoiles” [“When the stars appear”], shows the knight attempting to focus despite public distraction. With distinct emotional tension Furlanetto holds the verse “Je fais ma prière à tes yeux” [“Unto thine eyes I say my prayer”], until one of the youthful rivals insults his honor. After fending off the start of swordplay, Quichotte resumes his serenade with mandolin, complimenting “La fleur de tes lèvres” [“the flower of your lips”]. Upon repeating this line herself, Dulcinée joins the principals to settle the struggle for her devotion. In her attempts to “modérer votre ardeur” [“temper your enthusiasm”], Margaine assumes multiple vocal identities, so that she remains attractive to both Quichotte and to Juan and persuades them not to “spill blood” [“répandre du sang”]. Once she dispatches the Chevalier on a mission to retrieve her stolen necklace, Quichotte glows with the assumption of affection. Here Furlanetto stands transfixed at Dulcinée’s balcony while intoning slowly “Elle m’aime” [“she loves me”], and — more slowly — “sa voix” [“her voice”], so that he nearly gels into a statue. The final two verses of the act preview by their performance here the eventual course of this one-sided liaison. Quichotte insists that his word is sacred, which Furlanetto emphasizes with a dramatic descending pitch on the vow that the will keep it [“je veux la tenir”]. Offstage Margaine repeats with an equally distinctive note of resignation Dulcinée’s original sentiment of the woman of twenty years.

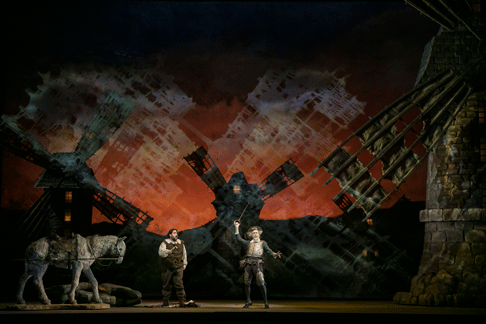

The second and third acts of Don Quichotte allow the audience both to appreciate the steadfast relationship between the Chevalier and his squire Sancho and to test the vow of the errant knight in fulfilling his promise. On the scrim before Act II a citation from Cervantes reminds the audience that Quichotte will courageously perceive windmills as giants. While riding through a bucolic landscape Quichotte attempts to compose a love poem for his lady. As Furlanetto becomes progressively rapt in his thoughts, Sancho remarks sympathetically “Enfin il est heureux!” [“He is finally happy!”]. The sentiment soon shifts to Sancho’s resentment over having presumably been duped by Dulcinée. Mr. Alaimo unleashes an extended judgement against “Les femmes” who continue to leave an husband simply scratching his head. Alaimo becomes vocally and physically involved in his accelerating characterization. With a forte declaration “L’homme est une victim” [“Man is a victm”], he equates husbands with “des saints” in a line which Alaimo concludes on a dramatically extended pitch. His impressive aria is interrupted by Quichotte’s spotting “les Géants” whom he intends to challenge with his lance. The scene renders Sancho’s renewed sympathies, and Alaimo cries with a gasp, “O fatale démence!” [“O fatal madness!”]. Once the knight is caught and carried up by the blade of a windmill, Sancho is left to pray for deliverance. After an orchestral interlude played at the start of Act III, both men proceed into the mountains at sunset. It is in this act that Furlanetto’s portrayal of Don Quichotte reaches its apotheosis while he declares heroically to his squire, “notre gloire commence!” [our glory begins!”]. Quichotte is now certain that he has found the path of the bandits who robbed Dulcinée’s necklace. With determination he repeats the start of his dedicatory chanson of love before gleefully declaring to Sancho that he sees at least two hundred opponents. Quichotte, who must face them alone, is now vanquished and surrounded by the group intending to kill him. With eyes directed to heaven and hands joined, Furlanetto sings the moving prayer, “Seigneur, reçois mon âme” [“Lord, receive my soul”], which he concludes piano on the line “I am yours.” Through vocal persuasion the chevalier arouses wonder in his adversaries; as leader of the bandits Mr. Smoak summarizes their reaction in his pointed questions on Quichotte’s purpose. In his proud response Furlanetto identifies himself as a knight redressing wrongs, describing his specific goal here, with the caveat that not the jewel, but “la cause est sacrée” [“the cause is sacred”]. The necklace is at once surrendered as Quichotte calls out to Sancho. The squire returns to witness the “miracle” of the converted ruffians, whom Quichotte can now characterize as “docile” in Furlanetto’s triumphantly held pitch.

The return to Dulcinée’s court and Quichotte’s unexpected departure are portrayed succinctly in Acts IV and V. Although surrounded by merrymaking and adulation, Dulcinée fails to be contented with the affections of her current suitors. She declares them objects of boredom as Margaine launches into her aria “Lorsque le temps d’amour a fui” [“when the time for love has fled”]. Starting with a slow and contemplative tempo, the piece increases in both intensity and volume as the heroine is joined by the chorus. Just as the determined suitors join in the song, Sancho announces the successful return of Quichotte. When Dulcinée learns that her necklace has indeed been returned, Margaine declares with emotional fervor, “Il faut que je t’embrasse!” [“I must embrace you”]. This sign of affection remains, however, attached to the bauble, for Quichotte’s subsequent offer of marriage is rebuffed with disbelief. Although Dulcinée’s explanation of emotional noncommittal is credited to her own needs, the courtiers can only deride Quichotte for his foolish desires. In a gesture of extremely touching loyalty Sancho chides the courtiers for their callous laughter at a man whose life has been determined by ideals and the perception of truth. Alaimo concludes this scene vocally with perhaps the most moving involvement of the production, as he lifts Quichotte to his feet and helps him to depart from an unwanted public display. In the final brief act in the mountains this powerful camaraderie is repeated when Sancho must support the head of Quichotte in his final moments of life. Furlanetto reminds his squire that he can leave him “l’île des Rêves” [“the island of dreams”] in their parting dialogue. In Alaimo’s anguished “Mon Maître adoré” [“My beloved Master”] we sense that this legacy will be cherished.

Salvatore Calomino