When Les fêtes d'Hébé appeared in 1739 Rameau was at the height of

creative powers and popularity. Masterpieces such asHippolyte et Aricie, Les Indes galantes and Castor et Pollux had flowed from his pen in the preceding few

years, and Les fêtes d'Hébé was one of his most acclaimed works

during his lifetime, receiving nearly 400 performances after its premiere,

before gradually fading from the repertory following the composer’s death

in 1764.

It seems incredible, therefore, that Les fêtes d'Hébé has not

previously been staged in the UK. All credit, then, to the combined forced

of the Royal College of Music, the Académie de l’Opéra national de Paris,

and the Centre de musique baroque de Versailles for bringing Rameau’s

charming, colourful ‘entertainment’ to London for the first time.

Les fêtes d'Hébé

presents considerable challenges, though, and not all the outcomes were

successful. First, the ‘tale’ Rameau tells is slight, the three parts

hanging together by the slenderest of threads. Hébé, the goddess of youth

cupbearer of the gods, is bored with life on Olympus and irritated by the

unwanted amorous advances of Momus. So, with her retinue of Graces, she

wings it down to earth in search of other delights, alighting on the banks

of the Seine, where Cupid advises her to mount a spectacle in celebration

of the three talens: ‘la poésie’, ‘la musique’ and ‘la danse’.

(And, indeed, where better than the environs of L’Opéra to enjoy such

‘talents’, for in the early eighteenth century, with the Revolution still

fifty years away, this Parisian institution remained the preferred

gathering place for high society and intellectuals, and a symbol of the

glory of the French monarchy.)

So, much like the English masque, the opera-ballet has no plot worth

mentioning but lots of visual spectacle and flamboyance together with

elaborately engineered stage effects. Can the refined aesthetic of the

eighteenth century - the highly ornamented and stylised cadences, the

gentle artifice, the convoluted ‘narrative’ - be made appealing to

twenty-first-century audiences?

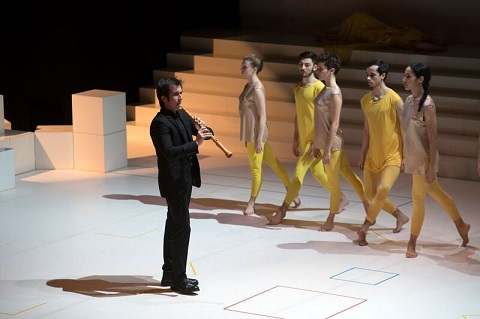

James Atkinson, Eleanor Penfold, Joel Williams. Photo credit: Studio J'Adore Ce Que Vous Faites.

James Atkinson, Eleanor Penfold, Joel Williams. Photo credit: Studio J'Adore Ce Que Vous Faites.

With a budget considerably less than that enjoyed by François Boucher when

he supervised the set designs at the Palais-Royal theatre in 1739, Thomas

Lebrun (director, set designer and choreographer), Françoise Michel

(lighting designer) and Laurianne Scimemi Del Francia (costume design) went

for a minimalist, colour-themed approach, bathing each of the acts in a

single hue - blue, yellow and red - and adding some bucolic projections.

The result was stylish and clean, but not particularly helpful in terms of

communicating who was who and what they were doing as they repeatedly and

randomly moved small white blocks about the stage. The cast is large and

the singers and dancers reappear in different roles. It all looked pretty

but I didn’t have much idea what was going on.

Lebrun’s choreography was fairly abstract but lithely danced and not

unappealing. It didn’t seem designed to serve a ‘dramatic’ function,

though. The modern idiom was also somewhat at odds with the musical

aesthetic, in a work in which dance, song and choruses come and go with

integrated fluidity. Some of the abundant dance numbers are adapted from

harpsichord pieces Rameau had previously published and the music is

ravishing. One can agree with Charles Burney who wrote in 1789, ‘More

genius and invention appears in the dances of Rameau than elsewhere,

because in them, there is a necessity for motion, measure, and symmetry of

phrase.’ However, Lebrun did place the ballet, particularly in

Terpsichore’s final apotheosis of the art of dance, at the heart of the

entertainment, and sequences such as that which accompanied the Oracle’s

announcement of Tyrtaeus’ victory in the second act were absorbing.

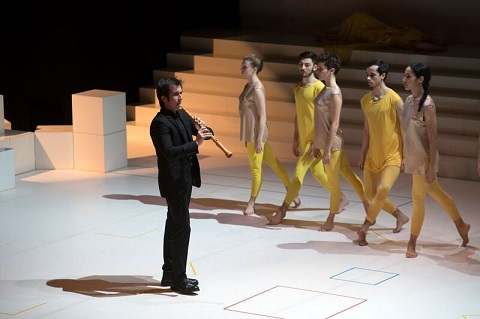

Andres Villalobos as Palemon (Oboe). Photo credit: Studio J'Adore Ce Que Vous Faites.

Andres Villalobos as Palemon (Oboe). Photo credit: Studio J'Adore Ce Que Vous Faites.

The original cast comprised some of the greatest French singers of the

period, and the vocal performances here confirmed that there is a lot of

talent in the conservatoires of France and the UK. Rameau’s vocal writing

is elegant, expressive and well-placed for the singers if rather lacking in

variety and range of character. On the whole the soloists coped well with

the curlicues and artifice though inevitably they struggled to imbue much

depth into the characterisation. Adriana Gonzalez displayed a rich, plump

soprano as Sapho/Iphise while Pauline Texier soared smoothly at the top as

Hébé in the Prologue and was an engaging Églé in the final Act, wooing Juan

de Dios Mateos’ arrogant Mercury with charming persistence. Tenor Joel

Williams revealed an alluring voice as Oracle/a stream (there’s a part for

‘a river’ too …), and Eleanor Penfold, a Naiad, joined him in a delightful

duet in Act 1 during a fête galante mounted by Sapho to

celebrate their reunion. Tomasz Kumiega displayed a sure sense of the

style. The French chorus (directed by Olivier Schneebeli) were terrific.

Conductor Jonathan Williams pushed things along at quite a lick, sometimes

at the expense of the intonation and the insistent pace could not have

aided the singers’ efforts to inject some depth into their roles. Moreover,

pastoral needs a little more languor; and the small string section of the

Royal College of Music Baroque Orchestra inevitably could not summon the

richness that Rameau’s original audiences must have enjoyed.

Can a modern audience be made to care about the amorous shenanigans of

Sapho, Iphise and Mercury, or be absorbed by injustices and restorations

among mythical kings and deities? Probably not. The French baroque opéra-ballet is an acquired taste and one not naturally

suited to modern palettes. But, this ambitious production offered visual

and aural enjoyment and the three collaborating institutions should be

lauded for their efforts and for bringing Les fêtes d'Hébé to

life.

Claire Seymour

Jean-Philippe Rameau: Les fêtes d'Hébé

Hébé/Églé - Pauline Texier, Sapho-Iphise - Adriana Gonzalez, Amour/Cupid -

Laure Poissonnier, Momus/Lycurgus - Jean-François Marras, Thelemus/Mercury

- Juan de Dios Mateos, Hymas/Tyrtaeus - Mikhail Timoshenko, Alcaeus/Eurilas

- Tomasz Kumiega, A stream/A shepherdess - Julieth Lozano, Naiad/A

shepherdess - Eleanor Penfold, Oracle/A stream - Joel Williams, A river -

James Atkinson, Dancers - Karima El Amrani, Antoine Arbeit, Maxime Camo,

Lucie Gemon, Léo Scher, Julien-Henri Vu Van Dung; Director/Set

Designer/Choreographer - Thomas Lebrun, Lighting Designer - Françoise

Michel, Costume Designer - Laurianne Scimemi Del Francia, Royal College of

Music Baroque Orchestra, Les Chantres, singers of the Centre de musique

baroque de Versailles (director Olivier Schneebeli).

Britten Theatre, Royal College of Music, London; Thursday 6th

April 2017.