As we journey from the dungeon-esque darkness of the Queen’s nocturnal

demesne towards the gleaming sun-disc which bathes the final chorus in the

luminosity of enlightenment, a Dantesque night is truly turned into day.

However, in

2013

, I found the performance, while elegant and slickly choreographed,

‘disappointingly lacklustre’ and missing the sparkle of ‘simple youthful

vitality and dreamy enchantment’. Reflecting again, perhaps some of my

disenchantment derived from a perceived imbalance, on that occasion,

between allegory and artifice.

For, while some lines of the opera’s libretto are based on sources used by

the Freemasons, whose symbolism scholars have sometimes purloined in order

to argue that a hidden masonic allegory underpins the opera’s quests and

initiation rituals, in fact many of the magical and ‘marvellous’ episodes

derive from earlier operas, pantomimes and comic plays that would have been

well known to the audiences at Schikaneder’s the Theater auf der Wieden,

and I am of the view that any elements of ‘freemasonry’ that are present

are far less important than those of fairy-tale.

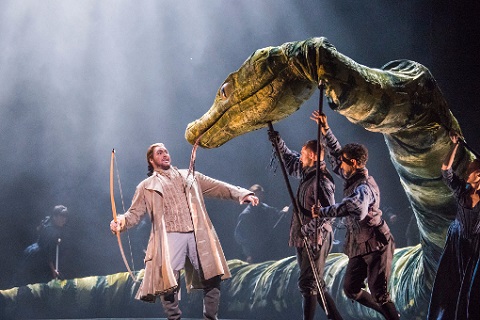

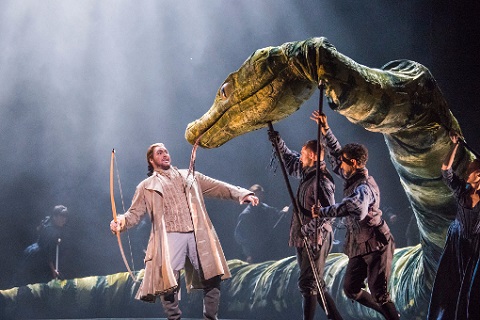

Mauro Peter (Tamino). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Mauro Peter (Tamino). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

During this performance, however, as the giant segments of the serpent

wiggled and waggled, expertly manipulated by the puppeteers, and the marble

columns of hallowed halls slid imperiously into dignified place as the

orrery spun in heliocentric harmony, it was the opera’s human concerns that

seemed more compelling than any abstruse philosophising.

And, for this more harmonious union of folky comedy and high seriousness,

we have Roderick Williams’ effortlessly warm-voiced Papageno to thank.

Williams is a seasoned bird-catcher having taken the role in several

productions, including Nicholas Hytner’s ENO long-lived production and Tim

Supple’s ‘grungy’ Flute at Opera North. But, even so, this

Papageno has some way to go before his earns his stripes as master of the

aviary. Outwitted by a puppet goose - I remember, too, an ‘incident’ with

some recalcitrant real-life doves at ENO! - he eventually learns his own

tricks, making the Priest’s feet (Harry Nicolls) dance to Papageno’s tune

in ‘Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen’. Williams evinces an easy physicality which

never drifts into farce and heaps of appealing guilelessness: who would not

be touched by fellow-feeling when this Papageno humbly voices his simple

desire for love and happiness? His cheek and charm certainly earn the

bird-catcher his perky Papagena-in-pink, though one suspects that he will

have trouble preventing Christina Gansch’s sassy slapper from

fluttering her feathers from time to time.

Roderick Williams (Papageno) and Mauro Peter (Tamino). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Roderick Williams (Papageno) and Mauro Peter (Tamino). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Williams’ expert comic timing was matched by that of Peter Bronder’s

Monostatos. There was a ‘nasty’ edgy to this villain’s lasciviousness

which, together with the masked beasts and vultures, suggested a darker

vein in the pantomime.

Several of the cast are making their Covent Garden debuts and this was a

significant incentive to see this revival. In particular, I was very keen

to hear French soprano Sabine Devieilhe scale the Queen of the Night’s

stratospheric peaks, having greatly admired her performance as Bellezza in

Handel’s

Il trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno

at Aix-en-Provence in 2016. And, she didn’t disappoint: ‘O zittre nicht,

mein lieber Sohn’ was absolutely secure and clean-toned, but ‘Der Hölle

Rache kocht in meinem Herzen’ simply took my breath away. I’m not sure how

such a glacial tone can intimate ‘warmth’ or fullness, but somehow

Devieilhe managed not just to hit the top Fs but to shape and soften them.

Sabine Devieilhe (Queen of the Night). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Sabine Devieilhe (Queen of the Night). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

I’d previously been impressed too when I heard Australian soprano Siobhan

Stagg sing in Keith Warner’s ROH production of

Luigi Rossi's Orpheus

at the Sam Wanamaker Theatre at Shakespeare’s Globe in 2015, noting that

she combined ‘a ravishing tone with pinpoint accuracy.’ The purity and

richness of Stagg’s tone were put to good effect in her interpretation of

Pamina’s gentle innocence, for she infused the lovely sound with a firm

glint which suggested that beneath Pamina’s naivety lie integrity and

resilience. ‘Ach, ich fühl’s’ was unsentimental but deeply communicative,

though I wondered whether Stagg would have liked conductor Julia Jones to

have taken her foot of the pedal slightly - the aria followed rather

precipitously from the preceding aria although Stagg’s poise steadied the

ship.

Roderick Williams (Papageno) with Siobhan Stagg (Pamina). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Roderick Williams (Papageno) with Siobhan Stagg (Pamina). Photo credit: ROH/Tristram Kenton.

Mauro Peter’s Tamino might have had a little more ruggedness, but the Swiss

singer has a lyric tenor of great beauty and the polished artistry of his

phrasing and his careful diction certainly made his ‘princely’ mien

convincing: ‘Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön’ was tenderly love-struck. I

found that Finnish bass Mika Kares lacked the sonorous weight needed to

convey Sarastro’s authoritative sobriety - though I note that those who saw

earlier performances in the run disagreed.

The three boys - James Fernandes, Oliver Simpson and Jayden Tejuoso -

struck just the right balance between real boyish charm and pure

otherworldliness. Their three voices blended beautifully to form a single

gleaming thread of innocence and light; if one shut one’s eyes, one really

could believe that they had descended from celestial realms. But, their

interventions, preventing tragedy, were genuinely human. The three Ladies

were less consistent, Rebecca Evans, Angela Simkin (a Jette Parker Young

Artist) and Susan Platts coming adrift at times in terms of timbre and

temperament, and, occasionally, tuning.

Jones’ tempos were swift. As in 2013, I wished for a more spacious

composure at times for the opera presents both fury and sobriety, but I

enjoyed the ROH Orchestra’s sure sense of period style.

Revival directors Thomas Guthrie and Angelo Smimmo (movement) have made a

good job of polishing the ROH’s silverware and McVicar’s production

continues to shine. At the closing curtain, Macpherson’s sun-disc seemed a

perfect metaphor for Mozart’s opera: radiant and eternal.

The Magic Flute runs in repertory at the Royal Opera House until 14

October.

Claire Seymour

Mozart: Die Zauberflöte

Tamino - Mauro Peter; First Lady - Rebecca Evans; Second Lady - Angela

Simkin; Third Lady - Susan Platts; Papageno - Roderick Williams; Queen of

the Night - Sabine Devieilhe; Pamina - Siobhan Stagg; Monostatos - Peter

Bronder; First Boy - James Fernandes; Second Boy - Oliver Simpson; Third

Boy - Jayden Tejuoso; Speaker of the Temple - Darren Jeffery; Sarastro -

Mika Kares; First Priest - Harry Nicoll; Second Priest - Donald Maxwell;

Pagagena - Christina Gansch; First Man in Armour - Thomas Atkins; Second

Man in Armour - Sion Shibambu; Director - David McVicar, Conductor - Julia

Jones; Revival Director - Thomas Guthrie, Designer - John Macfarlane;

Lighting Designer - Paule Constable, Movement Director - Leah Hausman,

Revival Movement Director - Angelo Smimmo, Royal Opera Chorus (Chorus

Director, William Spaulding), Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Wednesday 20th

September 2017.