Do we need to know the political context in which a work was created in

order to fully appreciate its ‘worth’? Does that political context need to

be made ‘relevant’ to present audiences? There are no simple or ‘right’

answers to those questions, but in the light of director Daisy Evans’

decision to entirely discard Dryden’s original text for this performance of

Purcell’s semi-opera with the Academy of Ancient Music and to offer in its place something abstract and topical - ‘King

Arthur in the Age of Brexit’ - it might be worth reflecting on the work’s

origins and allegories. Evans’ declares that her production ‘isn’t about

King Arthur the legend, it’s about the idea of King Arthur’ - but isn’t the

latter just what Dryden and Purcell were reviving and engaging

with, too?

So, a brief re-cap. In the 1680s the Civil War was still a recent memory,

and political and religious divisions had the potential to re-ignite. As

the 25th anniversary of Charles’ restoration neared, plans were

made to celebrate it through grand architectural and artistic projects. A

new palace was built in Winchester, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, the

foundations of which were said to stand on the remains of the

castle that had been home to the court of King Arthur: the ceiling of its

great ‘St George’s Hall’ was lavishly decorated with a painting of Charles,

the north wall presented Edward III and the Black Prince, while at the west

end was St George and the Dragon.

Dryden drafted an Arthurian epic, a semi-opera with music supplied by Louis

Grabu, Charles’ former Master of the King’s Musick; but this was eventually

supplanted by Dryden’s Albion and Albanius, which was intended as

a prologue to King Arthur, presenting a thinly veiled allegory

concerning the ‘exclusion crisis’ (which had sought to exclude the Catholic

Duke of York - Charles’ brother, James - from the throne and have the Duke

of Monmouth declared the legitimate heir). As Dryden wrote, ‘the Allegory

itself [is] so very obvious, that it will no sooner be read than

understood’.

Six years later, though, Albion and Albanius was totally

unsuitable for the new political situation brought about Charles’ death in

1685, the deposition of James II in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the

ascension of William and Mary the following year. Dryden had converted to

Catholicism in 1685 and his loyalty to the new monarchs was mistrusted. In

1691, Dryden and actor-manager Thomas Betterton had to convince the censors

that they had altered ‘the first design’, and that King Arthur

would in no way ‘offend the present Times’.

The result was considerable allegorical obfuscation: most people would

identify William III with Arthur, but there are intimations of a seditious

allegory in which Arthur is Charles II and William III is Monmouth. The

final chorus ‘St George, the patron of our isle’, for example, alludes to a

‘foreign king’: ‘Our Natives not alone appear/ To court this martial

prize/Foreign Kings adopted here/ Their Crowns at home despise.’ King Arthur’s apparent patriotism may have been insincere.

Evans sets out to explore whether the ‘idea’ of King Arthur is ‘the model

of British worthiness we still want to stand up for’: she describes her

staging as ‘almost like a stage-invasion protest. There will be Brexiteers

and Remainers, and everyone will have a chance to give their perspective on

the current stage and meaning of British identity’. The music has been

reordered: things start with daylight, before the Brexit vote as if

‘everything can still be OK’, and move through ‘uncertainty and war, before

arriving at this state of frozen, nightmarish night, where no-one knows

what to think or feel anymore.’

Not much allegorical mystification there, then. Indeed, the production’s

intent is signposted by Brechtian flip-charts that tell us that we are not

in Dryden’s royal apartments, woods and groves, or in Merlin’s cave, but

rather in commonplace modern locales whose inhabitants are rent by

divisions: ‘A Street - Leave v. Remain’, ‘A Pub - Girls v. Boys’, ‘A

Nightclub - Idea v. Reality’, ‘A Station - Us v. Them’, ‘A Polling Station

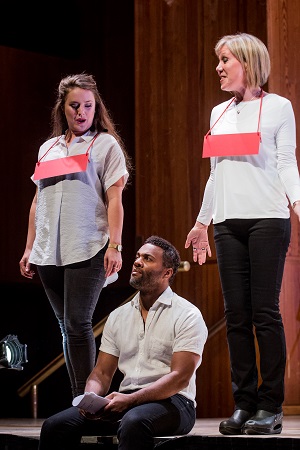

- Left v. Right’, ‘A Streetcar - Hope v. Despair’. Singers and

instrumentalists were in casual modern dress - all leggings, baggy

t-shirts, jeans and hoodies; but, in case we forgot that this was about

‘us’, the final poster reminded us, ‘The Barbican - Today’. The cast and

chorus swapped red and blue placards, which they hung around their necks,

to indicate their changing allegiances.

Photo credit: Louise Alder, Ray Fearon, Mhairi Lawson. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Photo credit: Louise Alder, Ray Fearon, Mhairi Lawson. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

It was hard to remember that King Arthur is essentially comic -

sometimes verging on pantomime - and that while Purcell’s music was never

intended to explore psyche or develop character it did advance the action

at times and certainly added to the atmosphere, ceremony and spectacle in

the manner of an English masque. Here, music and text seemed in opposition.

And, what of the text? Semi-opera integrated choruses, songs, dance,

instrumental numbers and spoken dialogue. Evans’ retains the latter verbal

element but, having jettisoned Dryden, has sought to replace the original

with a variety of poems that provide a ‘context of the music and Dryden’s

original sung texts’ and present ‘a strong and vivid view on the central

topics of nationalism and identity’ - both ‘for’, ‘against’, and ‘don’t

know’. So, we have ‘The Bloody Sire’ by Robinson Jeffers, alongside

Shelley’s ‘Prometheus Unbound’; Blake’s ‘The Garden of Love’ followed by

Rose Macauley’s ‘The Picnic’. Shakespeare (‘Henry V’), Wislawa Szymborska

(‘Hatred’), Charles Bukowski (‘Trashcan Lives’) and Arthur J Kramer

(‘Victory’) make up the textual tapestry that is brought to a close by T.S.

Eliot, ‘This is the way the world ends/ Not with a bang but a whimper’

(‘The Hollow Men’).

Perhaps the most successful was the first text, an extract from Ali Smith’s

‘Autumn’, which opened the performance as the sonorous voice of narrator

Ray Fearon drew the singers down the aisles of the Barbican Hall, their

eyes fixed on their mobile phones, to join him in his anaphoric

declamation: ‘All across the country, people felt …’ Throughout, Fearon

moved authoritatively through the cast - who themselves weaved around and

between the players of the AAM - but he could not overcome the inherent

problem of dramatic pacing and the different rates at which the ‘action’

moves forward during spoken word, song and music. Not all of Fearon’s

recitations - some, literally, read from a crib sheet (was this part of

Evans’ ‘design’?) - had equal conviction: he raced through the ‘Saint

Crispin’s Day’ rhetoric and shouted his way, breathlessly and without

nobility, to the end of Henry V’s ‘band of brothers’ oratory, as if he

didn’t quite believe in the words in this context and wanted to get to the

end as fast as possible.

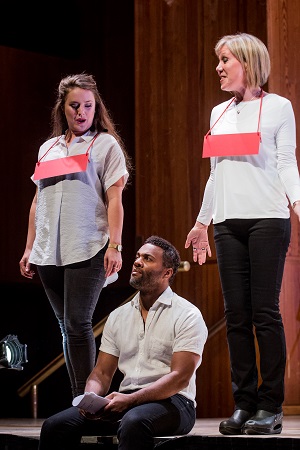

Photo credit: Ray Fearon (centre). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Photo credit: Ray Fearon (centre). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The singers, too, sometimes looked uncertain, as they took and shared

selfies, charged back and forth across the stage, read newspapers, ripped

the latter to shreds. Fortunately, they did not sound uncertain.

Mhairi Lawson sang with precision and agility, injecting colour and weight

into her soprano with expressive thoughtfulness. Louise Alder’s soprano

shone with richness and her arioso was sensitively shaped. Raised and

spotlit, at the end Alder looked as if she might burst into ‘Rule

Britannia!’ rather than ‘Fairest Isle’: the latter was characteristically

communicative although the interjection of spoken text over the air’s

instrumental introduction and inter-verse episodes was criminal. The two

sopranos blended well in their duets, often creating an air of

exhilaration.

After some intentionally ‘yobbish’ yells in the ‘Pub’ Scene, Ashley Riches

was permitted to show us the strength and elegance of his bass-baritone as

an excellent ‘Comic Genius’, prone and shivering during the strings’

strange throbbing introduction, then rising as if in imitation of the

ascent from beneath the stage which elaborate machinery would have effected

in Dryden’s day. Riches really captured the grave melancholy of the text.

Ivan Ludlow’s baritone had colour and breadth in ‘Ye blustering brethren’;

Charles Daniels’ tenor occasionally sound effortful.

Purcell provided Dryden with an abundance of varied musical numbers -

ritornelli, dances, preludes, chaconnes and ceremonial descriptions - and

Richard Egarr drew wonderfully light, fresh playing from the

instrumentalists of the AAM, himself leaping lightly to his feet time and

again to shape and guide with nuanced gestures. The sprightly rhythm for

strings and oboes which commenced the ‘Nightclub’ scene crept in with

Mendelssohnian animation and airiness; the closing cadence faded with

beautiful softness. Extreme dynamic contrasts were just that, dynamic;

accents were emphasised creating fleetness and momentum, especially in the

dances. The trumpets offered both a warm glow and pungent rawness, as

required. Part 2 opened with a tender ensemble for solo trumpet, violin and

oboe, accompanied by eloquent cello.

Overall, I found the stage business a distraction rather than an addition;

but, coherence and assimilation was and is an inherent problem in

semi-opera, so perhaps the struggle for integration of the various parts in

Evans’ concept is pretty authentic after all.

Claire Seymour

Purcell:

King Arthur

Academy of Ancient Music, AAM Choir: Richard Egarr (director/harpsichord)

Ray Fearon (narrator), Louise Alder and Mhairi Lawson (soprano), Reginald

Mobley (countertenor), Charles Daniels (tenor) Ivan Ludlow (baritone),

Ashley Riches (bass-baritone); Daisy Evans (stage director), Jake Wiltshire

(lighting director), Thomas Lamers (dramaturg)

Barbican Hall, London; Tuesday 3rd October 2017