Janáček assembled the libretto for From the House of the Dead

from Dosteovesky’s ‘memoirs’ which were loosely disguised in

quasi-fictional form and published, predominantly in the journal Vremya, between 1860-62. The composer selected

characters and incidents from the author’s accounts of ceaseless

suffering, as well as incidents that occurred in the prison hospital

and on feast days. Each of the opera’s three acts, which proceed

without pause, focuses on an individual narrative of the violent

crimes, real and sometimes imagined, which have led to incarceration.

The successive narrations of aggression, brutality and murder become

increasingly dreadful and distressing.

There is no development of character, but as Pountney so powerfully and

disturbingly confirms, Janáček creates incredibly probing psychological

studies. And, although individuals - the Tall Prisoner, the Short

Prisoner - emerge from and are re-subsumed into the mass of iniquity,

within the seemingly abstract design in which prisoners aimlessly

intermingle there is a huge range of emotions amid which an elusive but

indestructible hint of humanity survives. It is surely this combination

of abjection and compassion which attracted Janáček - who inscribed his

score, ‘In every creature a spark of God’ - to Dostoevsky’s

recollections. Just as the latter aims for objectivity in presenting

the extremes to which man may be driven in order to survive, as

violence begets violence, so the composer does not aim to explain,

condemn or absolve. The words of Carl Dahlhaus seem apposite: ‘In

contrast to Wagner, who keeps up the running commentary on the

unfolding drama, Janáček is not present in his own person, or

discoursing in his own words; he is more like an observer, standing

back unnoticed behind what he has to show us, which reveals itself in

its own terms.’

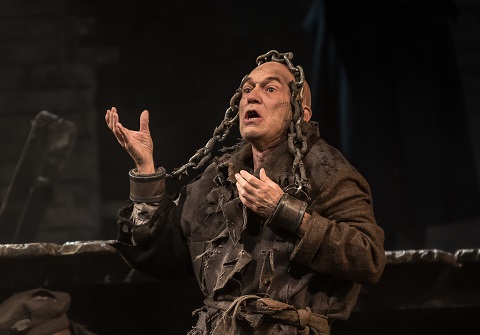

Cast of From the House of the Dead. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Cast of From the House of the Dead. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

From the House of the Dead

is all the more unsettling for Janáček’s unflinching realism. And, this

realism most forcefully resides in the astonishingly unconventional

orchestral score which Czech conductor Tomáš Hanus brought to life with

searing precision and incisiveness. WNO are performing the new critical

edition prepared by esteemed Janáček scholar John Tyrrell; heard here

for the first time, this authoritative edition further revises the

‘provisional’ edition based upon the 1928 copyists’ score (which

includes some of the composer’s revisions) which Tyrrell had prepared

with Charles Mackerras for the 1980 Decca recording of the opera.

Additions and instrumental doublings, along with the ‘ironing out’ of

the composer’s ‘idiosyncrasies’, which had been imposed by Janáček’s

pupils, Břetislav Bakala and Osvald Chlubna (who had believed the

chamber-like autograph score to be unfinished), have been pared away.

Hanus relished the instrumental extremes, creating a unalleviated

tension between bass and the soaring upper lines, and highlighting the

stark juxtapositions of colour - riotous brass, blazing trumpets,

squealing violins, and poignant oboe - and register - a low tuba

growling beneath stratospheric piccolo yelps - which characterise the

instrumental writing. The conductor achieved a wonderful transparency

through which every edgy motivic gesture, melodic snatch and rhythmic

twitch was laid bare. The mosaic-like structure of the score in which

textures and musical ideas seem almost randomly to intersect and

interrupt evoked the grim, grinding repetitions of prison life. The

overture, with its clanking chains, whiplash mimicry and high screaming

violins, was an alarmingly blunt exposure to the disturbing immediacy

of the events which would unfold. The opening march was intense: the

subdued horns rumbled forebodingly as the side drum rolled out the

signals which break up each monotonous day and evoke the oppressive

military force which overpowers all.

The perpetual tension never lessens: antagonism outweighs collective

experience as the prisoners constantly provoke and torment each other,

even arguing about the type of bird that they have captured and

confined to a cage. The aggressive rituals roll on and round, but at

times individuals are picked out for harassment, Chris Ellis’s lighting

(realised on tour by Benjamin Naylor) brilliantly isolating individuals

within the hellish gloom. And, the arrival of the aristocrat, Aleksandr

Petrovich Goryanchikov (the narrator of Dostoevsky’s novel), imprisoned

for political crimes, instigates a dreadful rattling of the prisoners’

chains. Dostoevsky had remarked, ‘They hated the upper classes to a

fantastic extent. They were extremely hostile and rejoiced at our

sorrow. They would have killed us had they been given a chance. They

never stopped persecuting us, for it gave them pleasure, distracted

them - it was an occupation’. Indeed, Ben McAteer’s clean tenor and

raised position on stage did seem to isolate him from the other

prisoners, but when at the end of Act 1 Petrovich was dragged away to

be beaten, Mark Le Brocq’s Luka Kuzmich’s account of his own similar

punishment caused the men - and us - to flinch with every audible crack

of the whip. The silencing of the prisoners’ voices at this point spoke

painfully of their anguish.

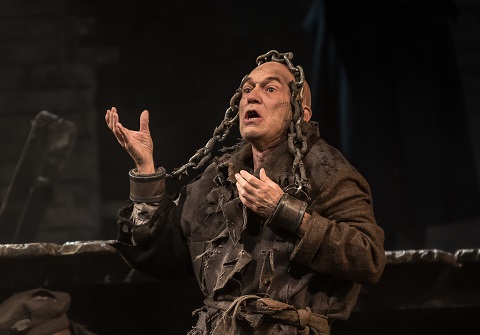

Mark Le Brocq (Luka). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Mark Le Brocq (Luka). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Luka is the first to recount his narrative of naked violence, and as he

told of his murder of a guard at another prison, Le Brocq’s tenor was a

formidable force against the abrupt and angular instrumental lines.

Alan Oke’s Skuratov is an unhinged presence during Luka’s account,

wrapping the chains which manacle his hands over his head as if to

inflict further pain upon himself. In Act 2, Skuratov tells his own

heart-rending tale about a woman, Luisa, loved and lost, and her Old

German husband, whom he murdered. The contrast between genuine love and

a rejoicing in murderous vengeance breaks out into a folk-song which

balances precariously between a reminder of the ‘real world’ beyond the

prison and a descent into lunacy. Oke skilfully evoked the different

voices of the personnel of his grim chronicle, momentarily transporting

us to the wider world.

It is Shishkov’s horrifically gripping narration in Act 3, however,

that descends to seemingly unredeemable depths of psychological

anguish. Simon Bailey was a commanding presence, emerging from the

obscurity where he had lingered up until this point to recount his

story of loyalty and betrayal. Bailey’s bass-baritone grew more intense

and compelling through his 20-minute confession. He had married

Akulina, despite Filka’s declaration that he had taken Akulina’s

virginity, but upon learning that Filka was indeed the man she truly

loved, he had slashed Akulina’s throat.

Alan Oke (Skuratov). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Alan Oke (Skuratov). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Amid such desolation, Janáček does offer tentative glimmers of

brightness. The role of the young Alyeya is cast for mezzo soprano

(though sometimes taken by high tenor) and Paula Greenwood’s shining

tone, her voice redolent with emotion as Alyeya sings of her sister and

mother, sailed above the prisoners’ sunken spirits - although such

moments of human warmth can make the resumption of prison life (the

noise of the convicts at work interrupts and smothers Alyeya’s

recollections) even more despairing. Then, there is the wounded, caged

eagle which the prisoners cruelly prod - to torment or keep alive? -

but which, a ‘Tsar of the forests’, recovers and is released, a

parallel to Petrovich’s new-found freedom. WNO’s representation of this

symbolic emancipation was not entirely successful, the somewhat clumsy

puppet of Act 1 replaced by projections for the final release - a

perfectly acceptable approach in theory, but a little unpolished in

execution.

The exaggerated gestures and flashes of colour which characterise

Pountney’s presentation of the two pantomimes which mark the Easter

festivities at the end of Act 2, emphasise the way the dramatic

narratives of ‘Kedril and Don Juan’ and ‘The Miller’s Beautiful Wife’

parallel the prisoners’ destructive experiences of sexual love. The

performances offer relief from the regimentation but also aggravate the

underlying tensions, emphasising the absence of women in the prison -

excepting the women who accompany the priest who offers an Easter

blessing and the prostitute who plies her trade - and the prisoners’

own failures.

Paul Charles Clark, Laurence Cole, Julian Close, Adrian Thompson. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Paul Charles Clark, Laurence Cole, Julian Close, Adrian Thompson. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The production also confirms the compassion and consolation that is to

be found amid such degeneracy and despair. Robert Hayward’s

Commandment, previously so brutishly angered by Petrovich’s dignity,

was almost lost for words when he asked Petrovich for forgiveness for

his unjust treatment. Peter Wilman’s Old Convict rose with surprising

fortitude and presence to affirm his reconciliation to camp life: after

Shishkov has attacked Luka (whom he has recognised as the treacherous

Filka), the old man calmly declared, ‘He was born of a mother too’,

though the prisoners’ struggle to comprehend what it means that ‘a

human being has died’.

In his last opera, Janáček eschews the climactic apotheoses and

melodrama with which some of his earlier operas close - and the sort of

romantic transfiguration of the kind that, depicting a similar context,

Franco Alfano indulges in the final scenes of Risurrezione

which I recently saw at the

Wexford Festival

. Pountney closes with the savage stamping of the concluding march

dissolving into the darkness. The oppression is overwhelming, the

routine will continue, unchanged: the realism of K át’a Kabanová pushed to its extreme.

Janáček wrote of his ‘black opera’ to Kamila Stösslova: ‘It seems to me

that I am gradually descending lower and lower, right to the depths of

the most wretched people of humanity. And it is hard going.’ Watching From the House of the Dead can give rise to similar dejection

and disorientation. But, the warmth of the lyrical exchanges between

Alyeya and Petrovich at the close bring both hope and frustration: the

latter’s freedom entails separation. Perhaps for the first time we feel

empathy.

Previous WNO tours have seen Tomáš Hanus at the helm for performances

of John Copley’s 2011 production of Johann Strauss II’s Die Fledermaus, but on this occasion the task fell to James

Southall who ensured that the bubbles did not go flat. The opening

chords popped like exploding champagne corks, kick-starting a

scintillating overture which set the tone for the entire orchestral

performance - one characterised by lightness and grace, rhythmic zest,

string playing which sparkled and then swooned, woodwind by turns silky

then razor-sharp, and spot-on tuning. Swift tempos kept self-indulgence

at bay - Southall didn’t over-egg the rubatos in the waltz - and

vivaciousness ruled the day.

Cast of Die Fledermaus. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Cast of Die Fledermaus. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Strauss’s belle époque frivolity seemed a rather odd companion

for the three Slavic dramas of the Russian Revolution

triptych. And, while it is a hangover from the company’s Vienna Vice season, there’s not much degeneracy or danger to

be found in Copley’s Viennese merriment despite the fact that the

criminal justice system lies at the heart of the drama of mistaken

arrest, prison avoidance and voluntary incarceration. But, given the

lessons learned when Christopher Alden looked for some darkness amid

the bats and ballrooms at

ENO

in 2013, that’s no bad thing. And, it’s certainly a

crowd-pleaser/audience-puller, offering some sunshine should the clouds

of Slavic gloom seem like heavy weather. Moreover, with Strauss’s

Viennese high society on the cusp of financial destabilisation and

members of the government being carted off to gaol for debauchery and

corruption, one doesn’t have to look too deeply to find some telling

contemporary parallels which add a delicate satirical frisson to the

light-weight comedy. The only difference is, perhaps, that nowadays we

are less likely to be surprised by the shocking behaviour of the

wealthy and the ruling classes.

Tim Reed’s elegant set gives no hint of imminent economic panic and

depression, however; in contrast, the graceful balustrades of the

spiral staircase which rise from the art nouveau tastefulness of the

Eisensteins’ drawing-room to the airy terrace balcony above seem an

aptly elegant metaphor for the social and financial ladder that the

would-be elite are rapaciously ascending.

Steve Speirs (Frosch). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Steve Speirs (Frosch). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The comic capers spin with a light touch, arising naturally from the

musical esprit, although the compulsion of Paul Charles Clarke’s Alfred

to burst into song - not just in his gaol cell, but also off-stage

before the show begins, and whenever the dialogue pauses for breath -

is a bit wearing, despite the tenor’s bright ring. Rossini, Verdi,

Puccini all get a look in, the latter somewhat anachronistically as

Rosalind is drawn into a ‘Nessum Dorma’ duet; and Alfredo, having taken Tosca a little too much to heart, flings himself from the

terrace balcony, only to bounce back up again. In Act 3, the drama is

momentarily put on hold by the arrival of Steve Speirs’ Frosch, whose

Tommy Cooper meets Macbeth’s Porter pièce de résistance was followed by Colonel Frank’s inebriated

ineptitude, ably delivered by James Cleverton whose distorted vision we

shared via some slippery coat-hook sliding and the over-active agility

of the Wilhelm I’s portrait’s florid moustache. It was quite a relief

when Adele (Rhian Lois) reappeared, confessing that she had been the

Eisensteins’ maid, and the music was restored to centre-stage.

Rhian Lois (Adele). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Rhian Lois (Adele). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The cast are uniformly attuned to the spirit of Copley’s production.

Judith Howard is a lively Rosalinde, only too aware of her husband’s

short-comings and dalliances. She slipped into a juicy cod-Hungarian

accent for her Csárdás and the high notes were similarly plump. At ENO

in 2013, Rhian Lois’s Adele was a welcome light amid the prevailing

Freudian shadows, and here she was similarly vibrant, delivering a

particularly glittering ‘Laughing Song’: Lois has obviously got the

role as securely under her belt as Adele has her wily ‘betters’ under

her thumb. I was impressed by Anna Harvey’s Prince Orlovsky, who for

once was not mired in misanthropic melancholy but merely seemed to wish

for some properly disinhibited partying. The challenging range and

leaps of ‘Ich lade gern mir Gäste ein’ (I love to invite my friends)

were negotiated with the same ease that saw Orlovsky throw back the

vodka shots and toss the tumblers over his shoulder.

Mark Stone (Eisenstein) and Ben McAteer (Falke). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Mark Stone (Eisenstein) and Ben McAteer (Falke). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Mark Stein’s Eisenstein was more harmless charmer than crooked cad.

Stone makes it all look and sound easy, but fashioning such musical

charisma and deft comic judgment takes hard work. Such is this

Eisenstein’s hapless inefficacy and vocal allure that one feels one

would forgive him any indiscretion. He’s even fairly patient with his

incompetent lawyer, Dr Blind (Joe Roche) and forgiving of Ben McAteer’s

cruelly vengeful Dr Falke. The slick couplets and adroit internal

rhymes of David Pountney and Leonard Hancock’s witty translation were

clearly enunciated by all - I rarely needed to glance at the surtitles.

Some of the choral numbers could do with a shot of Orlovsky’s vodka.

The WNO Chorus spin and swirl gracefully through the decorative arches

of the ballroom, but while their gowns dazzle and glint under Howard

Harrison’s purple-tinged light, the dancing is on the sedate side.

Hardly the wild nights for which the Prince longs. But, while Strauss’s

sachertorte may be a little too saccharine at times, the revenge of the

bat, silhouetted against the gleaming moon in the closing tableau,

provides some beguiling magic.

The WNO autumn tour

continues until 2nd December in Liverpool, Bristol and

Oxford.

Claire Seymour

Johann Strauss II: Die Fledermaus

Alfred - Paul Charles Clarke, Adele - Rhian Lois, Rosalinde - Judith

Howard, Gabriel von Eisenstein - Mark Stone, Dr Blind - Joe Roche, Dr

Falke - Ben McAteer, Colonel Frank - James Cleverton, Prince Orlovsky -

Anna Harvey, Orlovsky’s servant - George Newton-Fitzgerald, Ida -

Angharad Morgan, Frosch - Steve Speirs; director - John Copley,

conductor - James Southall, revival director - Sarah Crisp, designer -

Tim Reed, lighting designer - Howard Harrison, costume designer -

Deirdre Clancy, choreographer - Stuart Hopps, WNO Orchestra and Chorus.

Birmingham Hippodrome; Wednesday 1st November 2017.

Janáček: From the House of the Dead

Goryanchikov - Ben McAteer, Alyeya - Paul Greenwood, Luka Kuzmich/Filka

Morozov - Mark Le Brocq, Big Convict - Paul Charles Clarke, Small

Convict - Quentin Hayes, Commandment - Robert Hayward, Old Convict -

Peter Wilman, Skuratov - Alan Oke, Drunken Convict - Michael

Clifton-Thompson, Chekunov/The Priest - Alastair Moore, The Cook -

Laurence Cole, The Smith - Martin Lloyd, Young Convict - Adam Music, A

Whore - Sarah Pope, Kedril - Simon Crosby Buttle, Shapkin - Adrian

Thompson, Shishkov - Simon Bailey, Cherevin/Off-stage Voice - Gareth

Dafydd-Morris, Don Juan - Julian Close, A Guard - Joe Roche, Four

Actors - Matthew Batte, Nick Hywell, James Rockey, Dafydd Weeks. Female

Child - Lillyella-Mai Robertson/Iona Roderick; director - David

Pountney, conductor - Tomáš Hanus, designer - Maria Björson, lighting

designer - Chris Ellis, lighting realied on tour - Benjamin Naylor, WNO

Orchestra.

Birmingham Hippodrome; Thursday 2nd November 2017.