‘Enjoy the music of the never-enough-praised Monteverdi, born to the world

so as to rule over the emotions of others ... [which] will be sighed for in

future ages at least as far as they can be consoled by his most noble

compositions, which are set to last as long as they can resist the ravages

of time.’

[1]

Prophetic words. And, they were confirmed at the Camden Roundhouse where

the Royal Opera House and the Early Opera Company joined forces to present,

in a new English translation by Christopher Cowell, Monteverdi’s The Return of Ulysses.

It is music, as Monteverdi’s operatic dramas themselves argue and

illustrate, that speaks across generations and epochs. The words of

afore-mentioned author - ‘Monteverdi was born into the world to control the

feelings of others, there being no soul hard enough that he could not turn

and move it with his talent’, both singer and listener being ‘carried away

by the variety and strength of the same disruptive emotions’ - seem as

applicable now as in Monteverdi’s day. It seems to me, then, that there is

no need to find contextual or narrative parallels to emphasise or establish

the link between past and present. Homer’s poem communicates the grief of

absence and the joy of reunion, emotions with which all humanity can

empathise.

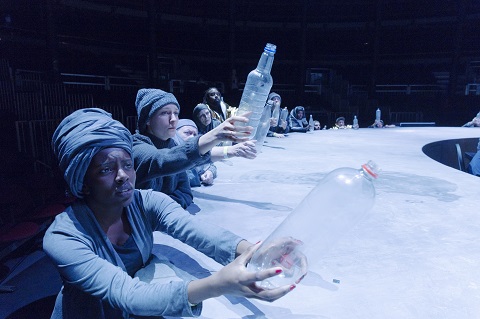

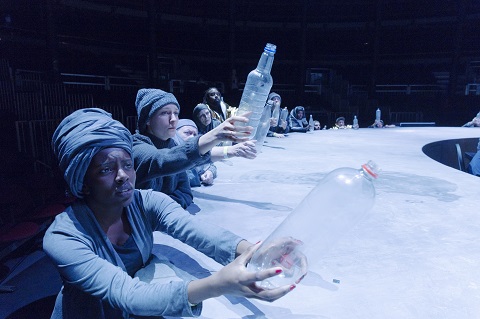

Production image. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Production image. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Director John Fulljames evidently thought differently. As well as excising

the gods and goddesses - and thereby eliminating some of the more effusive

lyrical moments in the score - he decided that ‘the question of living with

the legacy of war feels as if it’s the story of the 21st

century’, and that references to modern-day conflicts were in order: so,

the community choir became Syrian refugees receiving food parcels from the

aid-worker Penelope, and costumes juxtaposed buxom bronze breast-plates

with gold Doc Martens, and spangly space blankets with combat fatigues.

But, Ulysses is not ‘about’ refugees: the drama is impelled by a

‘home-coming’ which, in the opera’s final duet of reunited love confirms

the power of music itself. And, Fulljames neglect of this inexorable

progress towards inevitable resolution was problematic.

Tai Oney (as Peisander) with the community chorus. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Tai Oney (as Peisander) with the community chorus. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

As Ellen Rosand points out, each of the (original) five acts ‘culminates

with an action that marks a successive step in Ulisse’s journey homeward:

Act I ends with his rejoicing at his arrival in Ithaca, Act II with his

reunion with Telemaco, Act III with his vow to slay the Suitors, Act IV

with his defeat of the Suitors, and Act V with his reunion with Penelope’.

[2]

But, in this production, while no-one, not even the instrumentalists, was

ever ‘still’, there was no sense of anyone actually going anywhere.

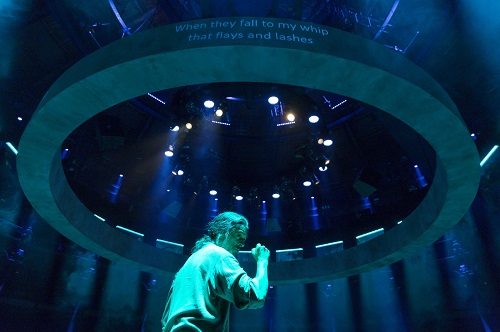

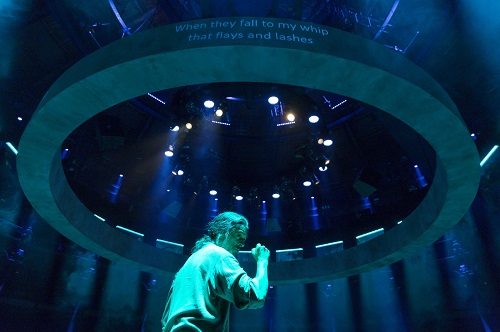

Ulysses (Roderick Williams). Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Ulysses (Roderick Williams). Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

When the ROH so successfully staged Orfeo at the Roundhouse in

2015

, Michael Boyd’s production was characterised by bold, dramatic movement,

exploiting the possibilities of the venue and capturing the vivacity of

Monteverdi’s strings of canzonetti and balletti through

the gestures of contemporary dance and show-ground acrobatics. Here, all

involved were confined to a central ring, which the singers circled as the

ring itself revolved, and into the ‘hole’ of which the Orchestra of the

Early Opera Company nestled, while they too rotated.

This incessant circling exacerbated the difficulty, posed by the dimensions

and nature of the venue, of creating sustained dramatic engagement between

the protagonists and consistent ‘connection’ between cast and audience. As

they orbited the musicians, in order to communicate with all ‘corners’ of

the Roundhouse singers frequently turned away from each other, disrupting

dramatic relationships. Moreover, the amplification that was so subtly and

effectively employed in Orfeo in 2015 was less successfully

managed here; voices seemed to ebb and flow, again making it difficult, for

this listener at least to concentrate, and to discern sustained dramatic

and emotional expression (though, the surtitles aloft - yet another ring -

were helpful).

The performance was not aided by the unfortunate indisposition of Christine

Rice. Rice mimed and mouthed the role of Penelope while Caitlin Hulcup -

who, we were informed, had learned the role in a single weekend - stood

among the instrumentalists in the doughnut-hole. Hulcup sang with

refinement and nuance; but, inevitably and unavoidably, the engagement

between the other characters and Penelope was lessened, as they sought to

encourage her to cast off her obduracy and anger.

Moreover, while the musicians of the Early Opera Group played for conductor

Christian Curnyn with customary stylistic elegance, the musical score was

unusually monotone of mood and detached from the dramatic unfolding. While

there is a stylistic gulf between the Mantuan Orfeo and the late

Venetian operas, Ulysses is still characteristically Monteverdian

in its juxtaposition of swiftly shifting emotions and affections, from

pathos to passion, despair to delight; but here rhythmic impetus and

variety often felt lacking. I barely registered the vivid sinfonia di guerra with its prickly concitato

incisiveness. The libretto bears the generic description ‘tragedia

’ but this attests more to the contemporary classicising aesthetic than to

a prevailing gloom, and I missed the alleviating heightening of lyricism

that occurs in Ulysses’ own vocal expansions, or the dramatic tension which

tightens the screw during the testing of the suitors, or the lascivious fun

and flippancy of the exchanges between Melantho and Eurymachus.

Ulysses (Roderick Williams). Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Ulysses (Roderick Williams). Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Pushing such misgivings aside, though, there is no doubting the eloquence,

both vocal and expressive, of Roderick Williams’ account of Ulysses’

trials. Williams sang beautifully: the gentleness of his baritone and the

sensitivity of his phrasing and dynamics seem custom-made for Monteverdi’s

tender, affecting arioso. But, while it was not entirely Williams’ fault,

given that he seemed to have been encouraged to sing much of the role while

lying on the floor, one might have found the characterisation rather

monochrome: this was a Ulysses in torment, but where was the joy and

laughter of ‘Rido, ne so perche’, the bristling bravery of the battle cries

or the passionate consummation of the final love duet?

Melantho (Francesca Chiejina) and Eurymachus (Andrew Tortise). Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Melantho (Francesca Chiejina) and Eurymachus (Andrew Tortise). Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

The ROH has assembled a strong cast and they without exception impressed.

Jette Parker Young Artist Francesca Chiejina was a vibrant, vocally lithe

Melantho - how did Penelope resist her servant’s seductive exhortations to

love? - and she was joined by Andrew Tortise’s Eurymachus in a beguiling

love duet (which is long, but in this context felt all too brief). Mark

Milhofer enjoyed the swineherd Eumete’s lyrical invocation to Nature, and

Susan Bickley provided concentrated emotional focus in the minor role of

Eurycleia. Catherine Carby, bashed about in brazen boots, and was a bubbly,

plump-voiced Minerva. As the suitors, Nick Pritchard (Amphinomus), Tai Oney

(Peisander) and David Shipley (Antinous) were vocally faultless but

struggled to make a dramatic impact.

Stuart Jackson was dressed in an ugly fat-suit and bald pate, but his Iro

was, ironically, handsomely mellifluous: indeed, one might question whether

Jackson’s characteristic vocal elegance and beauty were quite the right

channel for a character who lacks all pastoral grace as he repeats and

spits musical and verbal motifs? Jackson’s trills were crisp and stylish,

but did not conjure a demonic laughter that is a sign of imminent lunacy

and eventual, shocking, suicide. There is more depth and range of emotions

to this ‘comic’ role than Jackson perhaps intimated, however beautifully he

sang.

It was a pity that so much splendid singing was rather let down by a

production which span on the spot and lost its way. Monteverdi’s drama is

driven by the ever-decreasing distance between its two protagonists, but in

this production the distances between characters seemed to grow not

diminish. By the close, like Ulysses lost on the high seas for ten years,

they all seemed rather adrift.

Claire Seymour

Claudio Monteverdi: The Return of Ulysses

Ulysses/Human Frailty - Roderick Williams, Penelope - Christine Rice and

Caitlin Hulcup, Telemachus - Samuel Boden, Minerva/Fortune - Catherine

Carby, Eurycleia - Susan Bickley, Melantho/Love - Francesca Chiejina,

Eurymachus - Andrew Tortise, Eumaeus - Mark Milhofer, Irus - Stuart

Jackson, Amphinomus - Nick Pritchard, Peisander - Tai Oney, Antinous/Time -

David Shipley; Director - John Fulljames, Conductor - Christian Curnyn, Set

designer - Hyemi Shin, Costume designer - Kimie Nakano, Lighting designer -

Paule Constable, Sound design - Ian Deardon for Sound Intermedia,

Movement director - Maxine Braham, Translator - Christopher Cowell, The

Return of Ulysses Community Ensemble, Thurrock Community Chorus, Orchestra

of the Early Opera Company.

Roundhouse, London; Wednesday 10th January, 2018.

[1]

See Anthony Pryer’s ‘Approaching Monteverdi: his cultures and

ours’, in The Cambridge Companion to Monteverdi. The

author/librettist has recently been identified as Michelangelo

Torcigliani, friend of the librettist of Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, Giacomo Badoaro.

[2]

Ellen Rosand, ‘Monteverdi’s late operas’, in Ibid.