29 Jan 2018

William Tell in Palermo

This was the infamous production that was booed to extinction at Covent Garden. Palermo’s Teatro Massimo now owns the production.

This was the infamous production that was booed to extinction at Covent Garden. Palermo’s Teatro Massimo now owns the production.

The Palermitani, evidently less offended by abject sexual violence, tolerated the production’s humiliation and rape of a young woman without remark (having tacitly accepted as well Hunding’s gang rape of Sieglinde in last year’s Ring). Not that Damiano Micheletto’s William Tell production was not resolutely booed at this opening night of the Teatro Massimo’s one-hundred-twenty-first season. It was indeed.

It was a relaxed, festive evening at the Teatro Massimo, a red carpet runner ushering the very well-dressed audience past two magnificently uniformed guards at the entrance, shining swords at their sides. Never mind the heavy police presence in the piazza in anticipation of a demonstration (unrealized) against such extravagance.

At the hour the performance was to begin an announcement was made delaying the beginning by one-half hour due to a strike of some sort. No one minded as it was a very social evening, the animated conversations would have been hard to interrupt anyway.

Guillaume Tell, Rossini’s French style grand opera can be a very long evening (five hours plus in a recent Rossini Opera Festival production). In Palermo just now it was reduced to a bit over four hours, the act one marriage ballets were sacrificed, plus other less prominent sections.

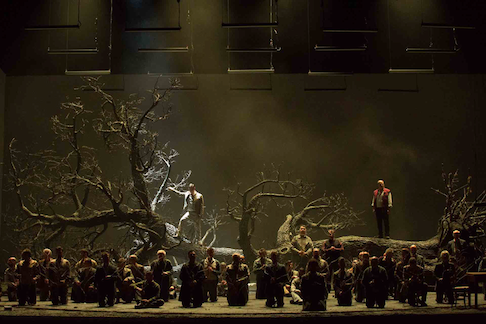

Dmitry Korchak as Arnold (in white light), Roberto Frontali as William Tell (in red vest)

Dmitry Korchak as Arnold (in white light), Roberto Frontali as William Tell (in red vest)

The Michieletto production reduced Rossini’s spectacle to bare bones — an illustrated comic book story (projected from time to time) was its cornice from which a surrogate William Tell emerged to cement William Tell’s patriotic resolve at crucial moments. Rossini’s quite specifically human, and complicated storytelling was transformed in Palermo into a ceremonial hymn to liberty, told in three bold strokes, Gesler’s thugs tore out the tree of peasant life (Gesler is the tyrant villain). The tree lay dead on the stage until William Tell eradicated Gesler. A new tree was planted as the Swiss peasants celebrated their emancipation from tyranny.

The effect of the production, and it was considerable, was exponentially increased by the expansive conducting of Teatro Massimo’s music director Gabriele Ferro. His tempos were indeed deliberate, elaborating the ceremonial tone of the production, the flights of lyricism were reduced to the beautiful sounds of the overture’s flute solo and to the splendidly voiced fisherman’s song that opens the first act.

After this it was all business. The chorus of Swiss peasants was grimly seated at regimented tables to grimly celebrate love, marriage and the harvest. William Tell got right to work liberating them through his heroic resolve, abetted by the heroic courage of his son Jemmy and the stoicism of his wife Hedwige. The murdered Melcthal’s son Arnold came to his senses and swore to avenge his father (though William Tell actually did all the work), not without the help of the Hapsburg princess Mathilda whom he loved.

Done.

The chorus and the principals then let Rossini’s final hymn to liberty soar, and it was spine tingling. The gigantic dead tree magically lifted (grand opera is famous for spectacular scenic effects, and this was just that) to allow a young boy to pass under with a sapling that he planted down stage center.

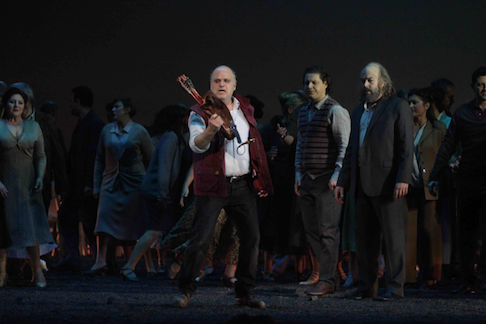

Roberto Frontali as William Tell

Roberto Frontali as William Tell

The Micheletto production was given vibrant life by an excellent cast whose voices and personae seconded its conceptual intentions. Baritone Roberto Frontali (San Francisco Opera’s recent Scarpia and L.A. Opera’s recent Falstaff) brought sharp edge to William Tell, no longer Rossini’s father figure he was far more a warrior. Soprano Anna Maria Sarra as William Tell’s son Jemmy was not diminutive, rather she was full-sized both vocally and morally, a warrior who mimed a child's movement.

Arnold, rendered impotent by love was sung by Russian tenor Dmitry Korchak in fine French and fine Rossini style. He was in love with Mathilde, the Hapsburg princess sung by Tbilisi (Georgia) born Nino Machaidze, a soprano of ample voice and great charm who negotiated her bit of fioritura with ease and to good effect.

William Tell’s stolid friend Walter Furst, sung by bass Marco Spotti, remained in the shadows, helping when called upon. Albanian mezzo Enkelejda Shkoza made Tell’s wife Hedwige a strong, purposeful presence supporting her husband and son, and a strong, purposeful voice in the upper registers of Rossini’s large ensembles, in Palermo executed with requisite magnificence.

The villain Gesler was delivered in high caricature by bass Luca Tittoto, underscoring the Italianate nature of this French evening (after all we were in Palermo!). Tenor Matteo Mezzaro, Gesler’s lieutenant Rodolphe, managed infectious charm in his nefarious duties.

The splendid first act’s fisherman’s song was sung by Sicilian tenor Enea Scala for the opening night performance only. He will sing Arnold in the final two of this eight performance run — the dynamic will be greatly changed. As the fisherman he and Enkelejda Shkoza were the only carryovers from the Covent Garden cast.

The orchestra and chorus of the Teatro Massimo seccured the solid artistic level of the evening, proving again that this Palermo theater is among the finest in Italy.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Guillaume Tell: Roberto Frontali; Arnold: Dmitry Korchak; Walter Furst: Marco Spotti; Melcthal: Emanuele Cordaro; Jemmy: Anna Maria Sarra; Gesler: Luca Tittoto; Rodolphe: Matteo Mezzaro; Ruodi: Enea Scala; Leuthold: Paolo Orecchia; Mathilde: Nino Machaidze; Hedwige: Enkelejda Shkoza; Un chasseur: Cosimo Diano. Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro Massimo. Conductor: Gabriele Ferro; Metteur en scène: Damiano Michieletto; Scene designer: Paolo Fantin; Costumes: Carla Teti; Lighting: Alessandro Carletti. Teatro Massimo, Palermo, January 23, 2018.