Holten’s Don Giovanni is entirely about making the most of Es

Devlin’s sets - and he does so even before the Overture, as lugubrious as

any I’ve heard, has even ended. Devlin’s sets are undeniably imposing - a

vast colonnaded front, with balconies and endless doors, balustrades and

hallways linked by stairways that disappear into infinity. At times I had

difficulty deciding whether I was looking in on a Romanesque temple or the

set of Hush… Hush Sweet Charlotte and the Hollis Mansion in its

antebellum, southern Louisiana horror. But just as Altman’s 1964 film had

been a study in psychological breakdown, of seeing ghosts at the top of

staircases, Holten extends his cinematic journey into his Don Giovanni still further by drawing us into Hitchcock’s 1945

study into psychoanalysis and surrealism, Spellbound, with his own

Dali-inspired Don Giovanni aria ‘Fin ch’han dal vino’ with the Don

as the centre of the eye amid a converging point of infinite distances.

If Holten’s production shares one thing with Bieito’s it is that both are

somewhat voyeuristic in their views of the opera, very much comfortable

with the objectification of sexuality. From the outset, Luke Halls’s video

design (this is very much a production for the digital age) gives us a

running count of the Don’s sexual conquests - and there are so many of

them, they cover not only every inch of the outside of the walls, but the

inside too… from the sides of staircases, the steps themselves, furniture,

even objects on tables. Echoing Escher’s stairs, the geometric set reflects

a sense of perspective and depth to this endless pornography. This graffiti

leaves an almost permanent stain throughout the entire opera, a reminder

that Don Giovanni’s existential sexuality is based entirely on deceit and

immorality embedded as it is deep within his psyche. It’s no coincidence

that his principle lovers are also damaged goods - the cluster of ink blots

on their dresses, Rorschach-like, but also reminders of sex itself. When

the litany of names are erased it’s to soak the walls in crimson blood, or

drench them in the bleakness of Don Giovanni’s mental psychosis.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Musically, this Don Giovanni is a bit of a mess. Textually, it is

neither the complete Vienna nor the Prague edition, nor the usual mixture

of both - and many will find excising ‘ Questo è il fin di chi fa mal’ from the end troubling, though I

think it better meets Holten’s objectives for this production to exclude

it. Holten’s Don is so psychologically flawed, so concerned with projecting

his pain onto others and using his sexual narcissism to seduce almost

everyone he encounters into complicity, that his descent into madness at

the end seems a more fitting conclusion. Holten’s Don is morally corrupt,

but as Kierkegaard also suggests desire is “victorious, triumphant,

irresistible and demonic”. The comparison with Faust is completely

unambiguous and, rather as the French novelist Jean Genet was fond of

suggesting when describing his own views on sex, this is a Don who is in it

for the chase alone.

The casting of Covent Garden’s revival is fairly strong, and, frankly, it

needs to be to fight against Marc Minkowski’s interminable and heavy-handed

approach he takes with much of the score; I thought Act I was never going

to end. This approach to the music doesn’t sit comfortably with the

dramatic visual changes that Luke Halls’s video design and Bruno Poet’s

lighting is presenting on stage - often what the eye is seeing isn’t

corresponding very closely to what the ears are hearing. Minkowski didn’t

always generate much enthusiasm from the orchestra either, so it was

perhaps all the more surprising that the singing itself was often of a very

high standard indeed.

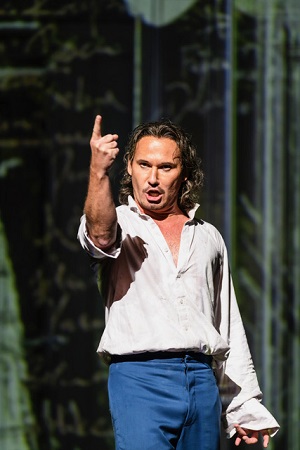

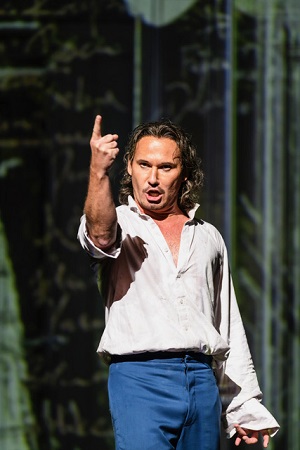

Mariusz Kwiecień as Don Giovanni. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Mariusz Kwiecień as Don Giovanni. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The Polish baritone Mariusz Kwiecień is the kind of Don Giovanni that seems

ideally suited to Kasper Holten’s production. In many ways, I found his

assumption of the part quite disturbing - he’s dynamically sexual, a

prowler, but the trajectory towards his mania is like watching a breakdown

happening in slow motion so deeply does he explore the depths of the

character’s underlying psychology. The voice is superb as well, a dark,

true baritone - like Eberhard Waechter’s - able to explore the demonic and

seductive sides of the Don’s personality. He was nowhere better than in his

final confrontation with the Commendatore, imperious of tone, the technique

immaculate, with just enough spine-chilling darkness to the voice. Perhaps

he was fortunate that his Leporello was Ildebrando D’Arcangelo. Kwiecień

and D’Arcangelo often subverted the master/servant equation, so much so

that Joseph Losey’s The Servant seemed like a model for their

unbalanced relationship, even with its latent hints of an uneasy masculine

derived sexuality. Although he sometimes looked as if he had fallen out of

a Chicago Sleep Easy, D’Arcangelo moved with breath-taking ease between

being a figure capable of easy-going humour one moment, and disturbing

violence the next. More so than in many productions, Holten views his

Leporello as a tragic shadow of Don Giovanni himself - even the

similarities in the voices that both these singers share suggested a much

closer alignment to their fates than normal.

Rachel Willis-Sørensen, as Donna Anna, never sounds vocally stretched (as

can sometimes happen with this role) and is as lyrical as she luminous.

Hrachuhi Bassenz, as Donna Elvira, is done with considerable intensity at

times, almost as if she is on the edge of hysteria. As with many of

Holten’s characterisations in this production, there is a sense that his

women, especially, are being driven into a kind OCD pattern of sexual

behaviour - coming back for more of the same, even though it is pushing

them into damaging psychological breakdowns. Both Donna Anna and Donna

Elvira are more complex women than we usually see in this opera, even if

what we see is quite disturbing.

As for the rest of the cast, Willard W. White, as the Commendatore, perhaps

lacks the depth of tone he once had to command the stage but was

compelling, especially in his showdown with Kwiecień - even if he looked as

if he had risen from George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, taking

to stalking Don Giovanni around the corridors like a zombie. Pavol Breslik

was a beautifully lyrical Don Ottavio, and convincingly handsome, Chen

Reiss a somewhat matronly Zerlina, and Anatoli Sivko a sonorous, if

ultimately unsympathetic Masetto.

Holten’s Don Giovanni probes deep, and Es Devlin’s sets, dizzying

though they are - quite literally - are visually spectacular. The entire

opera is a tour de force for its lighting engineers and someone

working on a laptop, but the length of time we are asked to engage in

looking at the staging borders on the cinematographic rather than operatic.

Likewise, the demands that Holten places on his audience and the questions

he asks squarely place Mozart the composer second. On opening night, the

cast sang well despite the conductor, not because of him - in other

circumstances this production might well be not so fortunate.

Further performances 3rd July until 17th July

2018.

Marc Bridle

Mariusz Kwiecień - Don Giovanni, Ildebrando D’Arcangelo - Leporello, Rachel

Willis-Sørensen - Donna Anna, Pavol Breslik - Don Ottavio, Hrachuhi Bassenz

- Donna Elvira, Chen Reiss - Zerlina, Anatoli Sivko - Masetto, Willard W.

White - Commendatore; Kasper Holten - Director, Amy Lane - Revival

Director, Marc Minkowski - Conductor, Es Devlin - Set Director, Luke Halls

- Video Design, Bruno Poet - Lighting Design, Orchestra of Royal Opera

House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Friday 29th June 2018.