This music is in Rattle’s blood and soul (and, he conducted the first half

of the programme from memory). As a nineteen-year-old, shortly after

winning the John Player International Conducting Competition in 1974,

Rattle conducted a concert performance of Ravel’s one-act opera L’enfant et les sortilèges in Liverpool, a performance which won

him great acclaim at the start of his career; thirteen years later he

conducted the opera at Glyndebourne, confirming his natural feeling for

Ravel’s meticulously refined soundscapes, pristinely ordered forms, and

ironic wit. He has made several recordings of the works comprising the

evening’s programme, often with the evening’s soloist, the Czech

mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kozena embodying the exalted princess, Shéhérazade,

or the wicked child whose tantrums result in his own torment.

Rattle’s ability to shine a gentle light between the gossamer layers of

Ravel’s orchestral scores, delicately illuminating the shifting tone

colours, subtle melodic utterances and splashes of brightness was evident

from the first few bars of the ‘Prélude’ to Ravel’s Ma M ère l’Oye, as the silky unfolding of the paired flutes and bassoon

hinted at the wide span of the imaginative world which Rattle brought

quietly but purposefully to life. And, though the dreamy wistfulness was

tinged with intimations of drama, danger was initially pushed aside by the

wonderful warmth of the string sound as the vista opened. The beautiful

string solos had plenty of space to breathe, and the solo double bass,

beneath clarinets and bassoons, slid deliciously down to the depths.

The Spinning Wheel buzzed and hummed, whirling with hypnotic momentum,

propelled by the whoosh of harp or flourish of celeste. In contrast, the

‘Pavane of the Sleeping Beauty’ proceeded with a measured tread, pizzicato

gestures disturbing the woodwinds’ meandering with a note of tension.

Rattle established a lovely waltzing lilt during the conversation between

Beauty and the Beast, finding a perfect balance between the various parts

but always encouraging those motifs that sustain the narrative to come to

the fore. The double bass pizzicatos had the feathery lightness of a

fairy’s kiss, and while Rattle ensured that contrabassoon had a dark weight

which conveyed the Beast’s menace, the transformation of the Beast was

stunningly magical - a transfiguration by harp and celeste culminating in

an expressive, warm violin solo by guest leader Giovanni Guzzo.

The even string lines at the start of ‘Petit Poucet’ (Hop-o’-my-Thumb]

painted Tom Thumb’s carefree progress through the forest and the cor

anglais had just the right degree of presence. Ravel’s exquisite classical

restraint and order was wonderfully communicated by the grace of line that

Rattle crafted. In the ‘oriental-flavoured’ transition to ‘Laidernonnette,

Impératrice des pagodas (Little Ugly, Empress of the Pagodas), what Ravel

called the ‘confectionary section’ of the orchestra - celeste, harp,

percussion - sprinkled sparkling magic dust; and the vivacity was enhanced

by xylophone and gong in the ensuing pentatonic dance which was

simultaneously graceful and restless: Rattle negotiated the metrical

modulations with compelling naturalness - as if a mesmerised reader was

turning the pages of a fairy-tale with unstoppable momentum. And, then came

the glories of ‘The Fairy Garden’: the strings’ luscious tone, the slow and

grave ambience, the heart-tugging phrasing all worked their magic. Rattle

showed his feeling for the smallest temporal detail, as in the slightest

rubato at the start of the final string statement which swelled from pianissimo to a blazing triumph of swirling instrumental colour

with uplifting nobility.

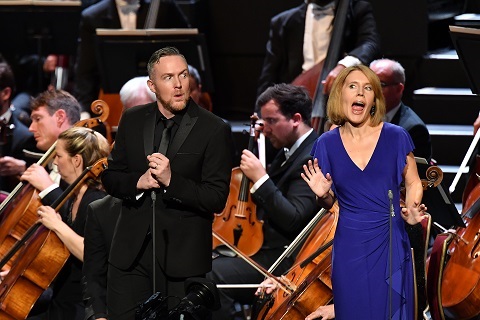

Magdalena Kozena (Shéhérazade). Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Magdalena Kozena (Shéhérazade). Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

The story-telling was entrusted to Kozena in Ravel’s Shéhérazade, and,

singing the vocal cycle that she recorded with Rattle and the Berlin

Philharmonic in 2012 for Deutsche Grammophon, she proved as persuasive a

narrator as her husband, who complemented the princess’s tales-for-survival

with pointillistic precision and refinement. Kozena’s mezzo was sumptuous

and radiant in ‘Asie’, unfailingly focused, even across the registers,

sultry at the bottom and shining in the middle-upper blooms; her French was

fairly idiomatic, and she was certainly attentive to the consonants even if

the vowels didn’t always have sufficient Gallic languor.

Rattle did not miss a single gesture of rhetoric, even when Ravel asks for

whispers and wisps. At the start of ‘Asie’ the asymmetrical rocking of the

cellos and cool clarinet cross-rhythms perfectly captured the slightly

uneasy blend of sensuality and latent primitivism - which finds further

expression in the juxtaposition of harp and timpani motifs - as we set off

on an exciting, unsteady but unstoppable journey.

Her mezzo almost trembling with barely repressed sensuousness, Kozena

breathed desire - ‘I would like to see eyes dark with love and pupils

bright with joy’ - as the viola and celli tremolando and songful violin

solo offered an instrumental representation of the vocal emotions. And,

just when we were on the verge of being lulled into yearnful dreams, danger

surfaced in a sudden flash of vocal fire and instrumental vigour: a vision

of ‘greedy merchants with scheming eyes, cadis and viziers, who with a snap

of their fingers dispense at will life or death.’ Perhaps there was not

enough variety of vocal colour, to match the instrumental mood- and

place-conjuring of envisioned travels through Persia, India and China, but

Rattle pushed on fervently and with a growing sense of violence and

quasi-hysteria as the princess expressed her wish to witness juxtapositions

of ‘roses and blood’ and ‘assassins smiling as the executioner slices off

an innocent’s head’. The Bb peak, ‘I would like to see men die of love or

of hate’, proved a step too high but it mattered not as the curtailed

climax was swept up in intense instrumental ardour.

Principal flautist Gareth Davies bewitched with a lovely purity and

expressive freedom in ‘La Flûte Enchantée’, and voice and ‘flute song’

blended beautifully, though I’d have liked a little more hushed mystery -

Kozena was rather forthright, especially in the faster episodes. The slow

tempo Rattle adopted in ‘L’indifférent’ at first surprised and then

convinced, creating a tender and precious sound upon which the well-shaped,

silky, lower-lying vocal lines could rest. Kozena’s precision as she snaked

through the slippery chromatic lines with their enharmonic coils was

impressive: a veritable vocal spell.

The spells were rather more vicious and violent in intent after the

interval, though Rattle emphasised the symphonic dimensions of L’enfant et les Sortilèges, and regardless of the

beguiling colours and moods we were offered as we danced through the score,

the wit remained more tasteful than sardonic, and sometimes, perhaps a

little too restrained? I’d have liked more sense of spontaneity and a tad

more tartness to the irony.

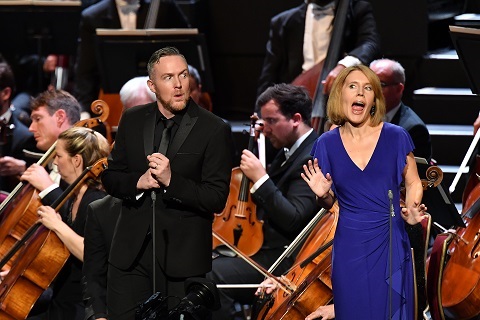

Magdalena Kozena (Child). Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Magdalena Kozena (Child). Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

But, this is to nit-pick. Rattle synthesised the eclecticism of the score,

revealing the meticulous polish, delicacy, proportion and elegance of

Ravel’s musical language and form. The tight nasality of the oboes’

parallel fourths and fifths captured the child’s restless ennui at the

start, and Kozena, now attired in sailor suit and cap, conveyed childish

insouciance and inconsequence; subsequently, she communicated the wicked

little boy’s realisation, growth and loss of innocence most potently.

Ravel distinguishes brilliantly between the coloration of the women’s

voices, and Patricia Bardon’s mezzo-soprano had a fulsome richness

befitting the Child’s ‘Maman’ - a lovely warmth which made Bardon’s later

duet with Jane Archibald’s chirruping Dragonfly, prone to stratospheric

micro-motifs, so heart-winning. Archibald’s embodiment of both the Fire and

the Princess was one of the highlights of this Prom. She relished the

floridity of Fire’s florid declaration, ‘Away! I warm the good, but I burn

the bad!’ - what a glorious frisson she produced on the sustained high A’ -

and as the frantic flames settled and Cinders rose, grey and sullen, from

the ashes, I had a moment of revelation - so this is where Britten found

the inspiration for the wood’s ‘sleep’ glissandi in A Midsummer Night’s Dream! Removing her ochre-tinted shawl,

Archibald moved to the rear, raised behind the strings, to sing an

impeccable plaint with the flute for her lost Cavalier - what stunning

two-part modal writing Ravel crafts here - and the low flute’s sad musings

were made so much more telling by the sudden rushes of rising pitch, and by

the fantastic lustre of Archibald’s vocal climaxes.

Jane Archibald (Princess). Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Jane Archibald (Princess). Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

This may have been a ‘concert performance’ but there was no lack of

communication, drama and interaction. Who could not envision the Sarabande

that Anna Stéphany’s Louise XV Chair dances with David Shipley’s slightly

louche Armchair, so flirtatious were the vocal glissandi; and Stéphany’s

China Cup was similarly coquettish as it engaged in the well-known frisky

Foxtrot with Sunnyboy Dladla’s big-hearted Wedgewood Tea-cup. My only

regret was that the instrumental nether regions - bass clarinet,

contrabassoon, trombone, tuba and bass drum - were so restrained! Might

Rattle not have let them off the leash a little, and encouraged them to let

rip?

Gavan Ring (The Black Cat), Anna Stéphany (The White Cat). Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

Gavan Ring (The Black Cat), Anna Stéphany (The White Cat). Photo Credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou.

As the naughty Child swung on the Grandfather Clock’s pendulum, the

pounding desperation of Gavan Ring’s ‘Ding, ding, ding!’, and the fervency

and fluency of Ring’s urgent lyric ascents, brought a lump to the throat.

Here, there was a smarting acerbity to the orchestral sound, though it was

the honest pathos of Stéphany’s Squirrel, caged in an unnatural prison,

that brought a tear to the eye. Ring and Stéphany delivered a Cat’s duet of

seductive beauty, accompanied by visceral orchestral swoops and swoons

which showed T.S. Eliot and Andrew Lloyd-Webber the fever pitch that feline

ecstasy can reach. Elizabeth Watt confirmed a real talent for vocal

characterisation as The Bat and The Owl.

Stravinsky called Ravel ‘an epicure and connoisseur of instrumental

jewellery’, and Rattle gave us a practical demonstration of what he meant.

This was stunning instrumental scene-painting revealing the power of

musical fairy-tale to recreate the grotesque and magical, and to summon

pastoral shepherds, insects, frogs and toads, dragonflies and nightingales

in other-worldly ardour. The final garden scene was headily atmospheric. Perhaps the LSO Chorus may have been more spiteful and vicious in wielding

their ‘talons’ and ‘teeth’ to reprimand the thoughtless Child, but at the

close Rattle drew astonishingly great tenderness from his vocal and

instrumental forces: a paradoxical childlike simplicity from rich musical

sophistication - a wonder to beguile children and adults alike.

Claire Seymour

Prom 48: Ravel

Magdalena Kozena - Child (mezzo-soprano). Patricia Bardon -

Mother/Shepherd/Dragonfly (mezzo-soprano), Jane Archibald - Fire / Princess

/ Nightingale (soprano), Anna Stéphany - Chair (La Bergère)/White

Cat/Chinese Cup/Squirrel (mezzo-soprano), Elizabeth Watts -

Shepherdess/Bat/Owl (soprano), Sunnyboy Dladla - Teapot/Little Old

Man/Tree-Frog (tenor), Gavan Ring - Grandfather Clock/Black Cat (baritone),

David Shipley - Tree/Armchair (bass), Sir Simon Rattle - conductor, London

Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Chorus.

Royal Albert Hall, London; Saturday 18th August 2018.