21 May 2019

Glyndebourne presents Richard Jones's new staging of La damnation de Faust

Oratorio? Opera? Cantata? A debate about the genre to which Berlioz’s ‘dramatic legend’, La damnation de Faust, should be assigned could never be ‘resolved’.

Oratorio? Opera? Cantata? A debate about the genre to which Berlioz’s ‘dramatic legend’, La damnation de Faust, should be assigned could never be ‘resolved’.

The work is a notoriously fragmentary hybrid, as quixotic as its eponymous ‘protagonist’, in which the unstable relationship between the ‘real’ and the ‘imagined’, between the ‘tangible’ and the ‘idealised’, is both the ‘perfect’ embodiment of Berlioz’s ‘meaning’ and irreconcilably opposed to coherent theatrical presentation.

That doesn’t stop people trying. And, any director who tries has fathom how to deal with the work’s innumerable gaps, inconsistencies, multiplicities and conflicts - in the music and in the drama, of style and of mode.

In the music there are symphonic narratives; oratorio-like choruses which comment on events in the past; set-piece marches, dances and songs, some diegtic; operatic recitative and quasi-aria. Sometimes the music takes us into a character’s consciousness and invites us to experience their feelings, as in Faust’s invocations in which the music presents his response to his immediate world, thus communicating his inner life. At other times, such musical empathy is denied us, such as at the start of the work when Faust tells us he can here choruses: ‘All hearts throb to their victory song.’ We do not hear such songs, and we remain alienated from his experience. Then, the music sometimes roots the action in reality: we hear students singing in the streets, military tattoos and fanfares.

The drama lacks tension. Characters sometimes address each other but they do not ‘converse’. Are their relationships real or allegorical? There are flesh-and-blood soldiers and students alongside flying demons and hallucinatory visions. Situations are often unspecified and discontinuous. For example, waiting in vain for Faust’s arrival, Marguerite sings the romance ‘D’amour l’ardente flame’: she could be anywhere, and the moment could be placed either before or after what we have just seen and heard. The action resumes subsequently, with Faust in the countryside. There is no clear chronology or causal relationship.

Ultimately there is no unity; and this is Berlioz’s intent. The real and the imagined meet on the stage and in the score. So, if one stages the work, what should the theatrical stage ‘represent’? An identifiable time and place? Or, a magical ‘anywhere’? Specificity destroys illusion; dream-like passages destabilise reality. Clearly a different, new kind of logic must prevail.

In this new staging at Glyndebourne, Richard Jones gives us his own brand of ‘logic’ but ‘coherence’ eludes him. Before we hear a note of music, dancing demons in lurid body suits and horned masks limber up, as if for a sporting contest; then, a chorus of fiends takes its place in the stalls perched on three sides above the black box set through the cracks of which lurid lights glow. These are, apparently, the students who will observe Méphistophélès’ masterclass in malevolence - though they might as well be spectators at a gladiatorial combat. Or an audience at the theatre, an effect enhanced when Méphistophélès turns to address us: “my devils”. Aloft, they resemble the chorus in an oratorio, commenting on the action; when they descend, they become participants in the drama, effecting ‘now-you-see-me now-you-don’t’ changes of costume which further makes the audience complicit in the deception of Faust.

Marguerite (Julie Boulianne), Méphistophélès (Christopher Purves) and Faust (Allan Clayton). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Marguerite (Julie Boulianne), Méphistophélès (Christopher Purves) and Faust (Allan Clayton). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

So far so good: the work’s hybridity is reflected in this conceit. And, if the work is to succeed on the stage it should surely do so on its own terms. But, immediately Jones starts meddling. The entry of a Méphistophélès - a Paganini-like figure, swathed in a black, embroidered trench coast, with lanky red hair and clutching a battered violin case - marks the first of Jones’s ‘amendments’: he has added spoken text, written by Agathe Mélinand and based upon Goethe but with, in Jones’s words, “what’s germane to Berlioz”. Presumably such text is designed to ‘fill in’ the gaps in the narrative but it simply unbalances the ‘theatre v. oratorio’ relationship still further - and it didn’t help that Christopher Purves’ weary opening lines had a few unintended hiatuses.

In a programme booklet interview, Jones also purports to have been influenced by cinema, describing the beginning of his Faust as “like Rosemary’s Baby, in the scene where they all meet in that spooky building on the Upper West Side … [which] looks Satanic”. Similarly, Choreographer and Associate Director Sarah Fahie alludes to “a Blue Angel version” of the Faust legend: Joseph von Sternberg’s 1903 film starring Marlene Dietrich. “Faust was the professor in The Blue Angle and the whole sequence by the Elbe was the club in the film ...” One might agree that Berlioz’s Faust would lend itself to cinematic presentation; one recalls the much-admired 2009 staging at the Met by Québec playwright, director and actor Robert Lepage, whose fusion of sound and image was summed by the appropriately allusive term ‘techno-alchemy’.

But, Jones and his designer Hyemi Shin rely on more mundane means, sliding kitchen tables, blackboards, doors, trees and other props on and off the stage to suggest the different locales visited or remembered by Faust, or dropping them from above: the cottage where Marguerite lives with her mother descends from the flies, as do the three lampposts that form a backdrop for the aforementioned ‘D’amour l’ardente flame’.

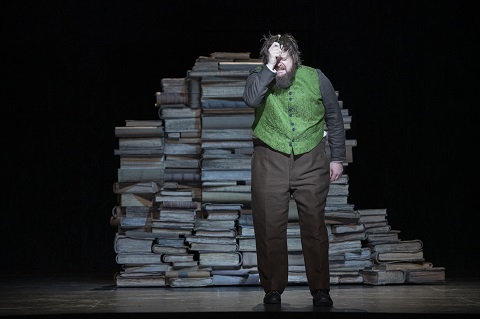

Faust (Allan Clayton). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Faust (Allan Clayton). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

There are plentiful recurring visual symbols: a portrait of the King of Thule, into whom Faust morphs at the close, sporting a scruffy white ti-shirt that spouts blood; a photograph of Marguerite, visible in the military students’ desks as they slam the lids up and down, disrupting the hapless Faust’s lessons on Romantic poetry, and posted on the front page of the newspapers held up by the chorus in the balcony, proclaiming her a Murderess. Jones deliberately bleaches such imagery of any Romantic idealism or lushness: it’s all broken and bereft, ugly and passionless. Even during their ‘love-making’, Faust and Marguerite have to be directed by the demons to slap a buttock, clutch a breast, thrust a hip. Marguerite’s mother shuffles back and forth in pink slippers and a stupor, drugged by the daughter who holds a tankard to her lips and roughly pours poison down her tilted neck.

Berlioz’s Faust is not Goethe’s over-reaching idealist who longs for the knowledge which is truth; instead, he is a man consumed by boredom, a man whose response to music - such as the Easter hymn which draws him back from the suicidal brink - is the sole thing that keeps alive transcendent desires which, however, remain unfulfilled. Scholar Daniel Albright has described this ‘anti-Goethean’ Faust, as a sort of ‘dead frog seeking Prof. Galvani for an electric charge’, and Allan Clayton seemed to embody such a figure at the start: listless, apathetic, heedless of the future. Though introspective, he was pulled from his inward gazing by external objectivities. This is a big sing and Clayton mounted a valiant essay, singing with earnestness and dramatic nuance; but he doesn’t have the high notes for the role, and this further diminished Faust’s already fragile heroic dimension.

The role of Marguerite is not enormously interesting for a singer: essentially passive, Marguerite has to be both sublime and real. While Julie Boulianne conveyed her innocence, it was a purity of a rather vacant kind. And, a reticent one: perhaps intended to infer delicacy and sweetness of character, the effect was disengaging, particularly as Boulianne’s enunciation was so poor. She grew in stature, strength and warmth in the post-dinner-interval Part IV, however.

Purves sang with a lovely seductive colour and nobility of line - not all that apt for the dark fiend, but pleasing to the ear, nonetheless. And, this Méphistophélès was a winner. Marguerite’s apotheosis was presented as a self-deluding indulgence of the disorientated Faust’s imagination; as Méphistophélès nonchalantly conducted ‘his’ choir of angels, it was plain who was calling the shots. As Brander, Ashley Riches dangled a rat before the terrified Marguerite with wicked glee and sang with assurance.

Conductor Robin Ticciati’s approach was perplexing. Carefully, oh so carefully, he gently teased out the nuances but so delicately, making us strain to hear the details, that we barely sensed the desire that the music communicates. The ‘big’ moments sometimes made their mark, but given the restrained, rarified tenor of the whole, the effect was one of discontinuity and disruption, adding to the incoherence of Jones’s conception.

Méphistophélès (Christopher Purves) and Dancers. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Méphistophélès (Christopher Purves) and Dancers. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

But, then, any semblance of theatrical or structural coherence was unfortunately destroyed by Jones’s final coup de théâtre. With the curtain re-raised and Méphistophélès apparently preparing to take his applause, we were halted in our tracks by the fiend. Just when I’d been reflecting that it was a pity that the dancers - who had largely just shimmied across the stage pushing props and set - had had so little to do, Méphistophélès demanded that, after the ‘entertainment’ he had provided, his band of devils should reciprocate. So, now came the Minuet of the will-o’-the-Wisps (which is itself a musical quotation from Méphistophélès’ serenade): a wild dance of Dionysian ascendancy. Berlioz ensures that Faust’s ideal, though unfulfilled, is kept alive at the close by the transfiguration of Marguerite: here, Jones stamped on such an ideal with hob-nailed boots and cruelly confirmed that it was as dead and buried as the dancing demon’s leaps were high and free.

Where does that leave the audience? How are we, like Faust, to be lifted from despair? To what are we to aspire? Jones’s vision was not simply bleak: just as Berlioz’s Faust is worn down by “mon ennui sans fin”, so, by the end of Jones’s production, was I.

Claire Seymour

Faust - Allan Clayton, Méphistophélès - Christopher Purves, Brander - Ashley Riches, Marguerite - Julie Boulianne; Director - Richard Jones, Conductor - Robin Ticciati, Associate Director/Movement Director - Sarah Fahie, Set Designer - Hyemi Shin, Costume Designer - Nicky Gillibrand, Lighting Designer - Andreas Fuchs, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Glyndebourne Festival Chorus, Glyndebourne Youth Opera Trinity Boys Choir, Dancers and Children.

Glyndebourne Festival; Saturday 18th May 2019.