The dedication was a paean to the head of the Roman Catholic Church: “the

most holy father, our lord Clement VIII, most excellent and great Pope.

Most blessed father and most merciful lord”. But alongside such pragmatic

and politic declarations lay more personal expression: “these tears of

Saint Peter … have been clothed in harmony by me for my personal devotion

in my burdensome old age’ (per mia particolare deuotione, in questa mia

hormai graue età).

For his texts, Lasso chose 20 of the 42 octava rima stanzas which

form the poem of the same title by Luigi Tansillo (1510-68).

Tansillo’s poetry describes not the act of denial itself, as dramatized in

Bach’s Passions, but rather the psychological after-effects of the agonised

glance given by Christ to the apostle Peter, directly after the third

denial, as recorded in the Gospel of Luke: ‘At that moment, while he was

still speaking, the cock crowed. The Lord turned and looked at Peter. Then

Peter remembered the word of the Lord, how he had said to him, “Before the

cock crows today, you will deny me three times.” And he went out and wept

bitterly.’

Peter then spends the rest of his life dwelling on his cowardice and error,

living in the eternal moment of betrayal and longing for the release of

death. In Tansillo’s poems, Peter contrasts his sin with the beatitude of

the children massacred by Herod and goes to the site of Christ’s

crucifixion where recognition of his undeniable and ineradicable cowardice

overcomes him. He retreats to a cave and spends his remaining days

repenting and, since self-forgiveness is impossible, yearning for divine

grace.

The stanzas set by Lasso focus solely on the lacerating glance of Christ

and its tormenting effect on Peter. Numbers 1 to 12 are concerned with the

piercing power of Christ’s glance, with the act of betrayal recalled in the

first four stanzas. The remaining 8 numbers tell of Peter’s self-rebuke;

from number 15, the third-person voice is replaced by Peter’s own. There is

no ‘narrative’ as such; rather the drama is internal, enacted with Peter’s

soul.

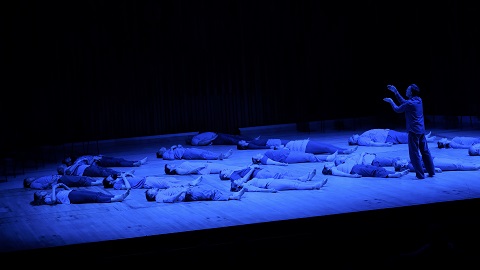

In 1559, the Vatican placed Tansillo on the Forbidden Index: his Lagrime prompted an official pardon from Pope Clement VIII. It is

tempting, and credible, to view Lasso’s Lagrime as an expression

of the aging composer’s own individual penitence - and this is the reading

adopted by Peter Sellars, the director of this kinaesthetic interpretation

of Lasso’s composition, presented by the Los Angeles Master Chorale at the

Barbican Hall. After all, the composer’s physical and mental state in his

final years is documented in deed and letter: in the form of a pilgrimage

to the Holy House of Loreto in 1585 and an appeal from his widow Regina to

Duke Wilhelm of Bavaria attesting to her late husband’s ‘melancholia’ - on

one occasion, he failed to recognise his wife, spoke often of his death and

was afflicted by sleeplessness and ‘fandasey’ (fantasies).

Others, though, including scholar Alexander Fisher

[1]

, view Lagrime in broader contexts: as a meditative

process that ‘served the ends of contrition for sin and, ultimately,

penitance’, and thus representative of post-Tridentine ‘sacramental

discourse’. Fisher notes that common to post-Tridentine Catholic meditation

‘is the devotee’s awareness of sin, lengthy mental examination of its

nature and consequences, and implicit or explicit resolution to make

amends, culminating in cathartic moments of dialogue with a divine

figure.’: ‘What is clear is that the Lagrime resonates deeply with

a specific brand of religious devotion that was assuming a dominant

position in Counter-Reformation Bavaria.’ Fisher views the closing Latin

motet, ‘Vide homo’, which follows the 20 madrigals as the conclusion of the

‘dialogue between individual sinner and saviour that was so central to

these methods. For those skilled in music, the steady ascent through the

modal system, culminating in the unexpected A durus [mode] as Christ

responds to Peter in person, would probably have strengthened the

impression of the Lagrime as a kind of spiritual journey leading

inexorably from the consciousness of sin to that moment in which all sin

was washed away’.

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

I allow that I digress here from the immediate purpose of this review but

feel the need to do so in the light of Sellars’ adamant declaration that,

“At this point in his life [Lasso] does not need to prove anything to

anyone. He is [composing Lagrime] because this is something he has

to get off his chest to purify his own soul as he leaves the world. It’s a

private, devotion act of writing, but these thoughts are now shared by a

community - by people singing to and for each other”. Arguing that the

chorus “carries the drama forwards”, Sellars suggests that the work accords

with the ancient Greeks’ understanding of tragedy, “which I could also call

an African understanding, where an individual crisis is also a crisis of

the community”. We hear one man’s thoughts, but it is the community that

absorbs them “and has to take responsibility: a collective takes on this

weight of longing and hope”.

Okay. Perhaps I should not have read Sellars' 'explanations' in the programme article - an extensive,

very informative historical, contextual, musicological and interpretative

account by Thomas May - before the performance itself. The latter was much

more persuasive.

Three singers are assigned to each of Lasso’s seven vocal parts. The

bare-foot singers are dressed in drab grey and mauve legging and slacks,

shapeless tunics and ti-shirts. I was surprised to find Danielle Domingue

Sumi credited as ‘costume designer’ - especially as conductor Grant Gershon

(also barefoot, in black) explains that they strove for ‘clothes that look

like they could come out of anyone’s wardrobe’: I thought they had. But, I

guess the drab attire reflected the blanched landscape of Peter’s

psychological wilderness. And, it allowed the singers to move naturally

around and across the Barbican Hall stage.

For, this is what Sellars conceives as a physical and kinaesthetic

representation of polyphony which is “totally sculptural”: the “muscular

intensity in Lasso’s writing [that] is reminiscent of this expressive

language we know so well, visually, from Michelangelo […] the muscle of

spiritual energy and striving against pain to achieve self-transformation”.

So, ritualised movements, complemented by surtitles in colloquial

vernacular, are designed to conjure the sculptural majesty of Renaissance

art and architecture. And, how impressive the Los Angeles Master Chorale

were in delivering harmonically and contrapuntally complex madrigals, their

voices blending seamlessly and mesmerizingly, all the while adopting

geometrical formations, pairings and poses; lying down, and sitting up;

standing alone in alienated misery and clutching colleagues in warming

consolation. Jim F Ingalls’ lighting followed the psychological

modulations, now bleached white, now cool aquamarine, then fertile gold, or

warming orange. Oh, yes; they had memorised the entire sequence - nearly 90

minutes of music.

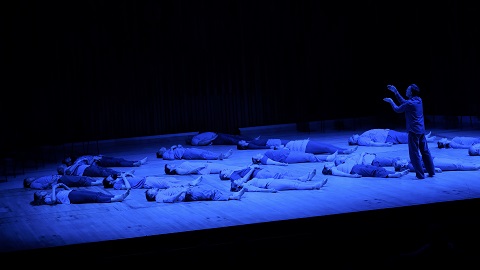

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

Would it have been preferable to have a single voice to a part? Perhaps I

would have liked greater presence from the soprano voices? And more shading

and variety of tempo? But Peter’s agonies were intensified by the smooth

sweetness of the collective lyrical expression. And, the attention to the

electric charge igniting the poetical text and detail was masterful, in the

madrigalian manner, and physically impressive. At the close of the 15 th madrigal (‘Váttene, vita va’ - Life, get you gone), the

chorus lay down, forming a crucifix: “Afraid to die, I denied life,” Peter

admits. How could the LAMC sing with such unified ensemble and sure

intonation from such a position?

The physicality of the performance was emphasised by sudden silences and

shifts, mimicking Peter’s psychological ups and downs. Some were dramatic,

others disruptive. I couldn’t help but recall the simplistic clichés of

school drama lessons at times. “The deadliest arrows that pierced his heart

were the eyes of the Lord, when they fixed on him …” prompted a collective

collapse to the floor (and, the singers stayed in tune …). There was much

handwringing, chest-clutching, colleague-embracing. When, for the final few

madrigals the singers retreated to chairs placed left and right, I felt

some relief.

Lagrime

closes with a Latin motet, setting the 13th- century French poet

Philippe de Grève’s representation of Jesus’s final words: a plea for

mankind to behold the Lord’s suffering - ‘Vide homo, quae pro te patior’

(Behold, man, how I suffer for you). The Lagrime, thus, end not

with consolation but with rebuke: we do not transcend despair. Fisher

argues that ‘Christ’s rebuke … is consistent with a reading of Lasso's

cycle as systematic meditation: the Lagrime, after all, concludes

with the reflection on sin and does not proceed further into the

illuminative and unitive.’

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

So, an accusing voice confronts not just Peter but mankind. But, Sellars

interprets such words as spoken in love: the chorus rise from their chairs

and embrace one another.

In cathedral naves, the human narrative of such works as Lagrime

can be lost; as the polyphony swirls around the vaulted ceilings, words are

lost in an embracing blend designed to render the individual receptive to

the divine. Sellars focuses on the psychological rather than spiritual,

setting the transience of human mortality against the almost unbearable

eternal present of the consequences of our actions. And, his reading is not

without power and pertinence.

Claire Seymour

Lasso: Lagrime di San Pietro (Tears of St Peter)

Los Angeles Master Chorale, Peter Sellars (director), Grant Gershon

(conductor), Jim F Ingalls (lighting designer), Danielle Domingue Sumi

(costume designer)

Barbican Hall, London; Thursday 23rd May 2019.

[1]

In ‘“Per Mia Particolare Devotione”: Orlando Di Lasso’s Lagrime Di San Pietro and Catholic Spirituality in

Counter-Reformation Munich’ Journal of the Royal Musical Association, vol.132, no.2,

2007: 167-220.