It is, namely, Mozart’s last work, a Requiem Mass left unfinished at his death in 1791, later finished —based on Mozart’s notes and sketches by his student Franz Saver Süssmayr. In this Aix edition it has been reconfigured and expanded by French musical visionary Raphaël Pichon, a conductor well-known at the Aix Festival, and by Italian theater visionary Romeo Castelucci in a belated, long awaited Aix debut.

But this “Mozart” Requiem is now a theater piece somewhat beyond, actually well beyond Mozart’s setting of the Catholic death mass liturgy. His widow Constanza pretended he composed his own requiem, and in Aix it was indeed just that — Mozart’s moment of life long vanished, conceptually the “Aix” Requiem insists that Mozart’s Requiem Mass will vanish as well.

Discovering this existential tragedy made the Castelucci Aix debut well worth the wait. In his Brussels Parsifal, his Lyon Jeanne d’Arc au Bûcher and his Salzburg Salome Sig. Castelucci is fettered by narrative, and imposed philosophical concept and psychological involvement. But in this Aix Requeim, like in his Tragedia Endogonidia cycle, he freely traverses ephemeral human atmospheres filled with unanswered questions that are met with spontaneous reactions. It is rare access to the most hidden theatrical realms of the human psyche.

Like the non-verbal, purely intuitive communicative process of music Castelucci’s language is the non-verbal communicative power of essential theater. There is no intelligence and there is no interpretation, there is but momentary recognitions of an intuited physical reality.

From its first moment in this Aix Requiem, a lone, older woman is perhaps at her death, the requiem passes through her four, simultaneous existences in identically dressed embodiments — a child, a virgin, a mother, and this old woman. The Aix Requiem ends with their issue — a baby alone on the silent stage. A male.

Musically the Requiem begins with the disembodied voice of a male child (soprano) intoning an anonymous Gradual (a response refrain normally sung between recitation of psalms): “Christus factus est.” It insists that the will of God be imposed on man. It is sung in the purest sounds of male innocence.

The usual requiem liturgies of praise and pain continue though interspersed by conductor Pichon with other Mozartian moments — a Masonic hymn, a Psalm setting, the reuse of a piece from his incidental music to Thamos Roi d’Egypte, a solfeggio (sung by the boy), an Amen, the parody of a Serenade, a church song. The Aix Mozart Requiem ends with again the lone voice of the boy intoning an anonymous “In Paradisum” (sung at the moment the body exits the church) — the will of God fulfilled.

There passed before our eyes an abstracted cruxifiction (the young girl), a forest, a maypole, a wrecked car, the Pygmalion chorus and four soloists of purest voices (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) intoning the liturgies first in the clothes they wore to the theater (a heat-wave in Aix), transforming themselves in courtly white unisex dresses, then in celebratory courtly crimson unisex robes, finally in muslin tunics for the "Agnus Dei" before decaying into a chiaroscuro mass of naked bodies. The complex choruses issued forth while the singers created the structures of the music in abstracted movement, often dance, impeccably carving the interlocking phrases of Mozart’s fugues to construct the technical grandeur of mankind’s accomplishment.

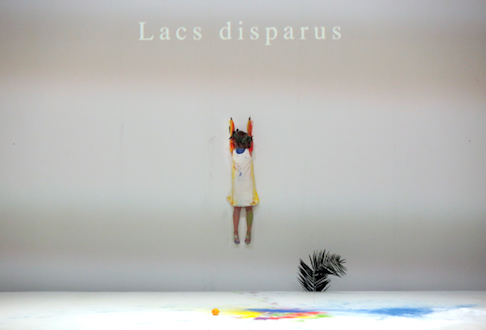

The coup de théâtre was the cataclysm that occurred in the "Communion" of the requiem liturgy, the souls becoming one with God shouting their jubilation, tearing down the white walls of the world. The floor of the stage slowly rose, becoming vertical, the debris of the wall and black dirt of the world randomly sliding down to reveal, finally, a blank, white wall. Death. Silence.

From beginning of the Requiem to its end continuous words streamed across the stage box, naming the now vanished accomplishments of man and nature. The final words, incised, were July 5, 2019 — the day I saw the Aix Requiem.

With, then, the lone male child — the creator — alone on the stage we were left with the finality of death, and the image of creation. There was no comfort in rebirth.

The stage was the music, and the music was the stage. Maestro Pichon’s Pygmalion orchestra of period instruments was the voice and the world of man, the solo winds of purest sound, of psychological innocence, the solfeggio violin duet with the boy soprano giving corpus to nature. The eloquence of the requiem liturgies ceaselessly emerged from the pit in crystal clear phrasing that created profound, truly human embodiment for this mass of death.

This Mozart / Pichon / Castelucci Requiem occurred in the most minimal terms. The chorus sang without score, the stage was but a white box. It was sublime music made alive in pure theater.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Conductor: Raphaël Pichon; Mise en scène, scénographie, costumes, lumière: Romeo Castellucci; Collaboratrice à la mise en scène et aux costumes: Silvia Costa; Dramaturgie:

Piersandra di Matteo. Chorus and Orchestra: Pygmalion. Soprano: Siobhan Stagg; Alto: Sara Mingardo; Ténor: Martin Mitterrutzner; Basse: Luca Tittoto; Enfant chanteur: Elias Pariente. Théâtre de l’Archeveché, Aix-en-Provence, July 5, 2019.