Michael Steinberg’s prognosis, expressed in The Boston Globe in

July 1976, is taking rather longer to be fulfilled than the eminent

classical music critic, writer and lecturer imagined. But, this performance

of Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin by Mark Padmore and

Kristian Bezuidenhout at Wigmore Hall will surely have done much to win

converts to the cause which Steinberg described over 40 years ago as a

‘Fortepiano Revolution’.

Standing at the centre of the Wigmore Hall platform, the grand fortepiano

from the workshop of Christoph Kern (located in Freiburg im Breisgau in the

Upper Rhine plain) was a beautiful sight to behold, its glossy

chestnut-cherry colour wood gleaming with an elegant grain, its graceful

curves evincing a quiet stylishness and assurance.

As Wilhelm Müller’s tale of the young miller’s journey - from awakening and

hope through delusion to rejection, despair and death unfolded -

Bezuidenhout revealed the expressive responsibility with which Schubert

endows the fortepiano part in ways that, for this listener at least, were

quite revelatory. The lightness of the sound was coloured by a judiciously

applied sharpness of attack, the clarity animated by such alertness, the

bass line robust but lithe. This was evident from the opening bars of ‘Das

Wandern’, where the low bouncing bass line and the rhythmic articulation of

the rollicking right-hand figuration possessed an unusual airiness,

perfectly capturing the buoyant optimism of the miller as he sets out,

untroubled by desire and delighting in the rushing brook that the piano

ceaseless motion embodies. Similarly, in ‘Wohin?’ Bezuidenhout was able to

achieve a truly hushed pianissimo, the fluttering

right-hand transparent and elegant, the syncopated bass eloquently swaying.

The rapid flickers in ‘Halt!’, as the miller espies the mill among the

alder trees, were gleamingly defined.

If dynamic range is not one of the fortepiano’s strengths, then

Bezuidenhout showed us that the instrument does offer variety, of timbre,

texture and colour. The softest passages were beautifully executed, with

stylish discernment and detail. Moreover, the more rapid decay of the

fortepiano’s tone seemed to become an integral expressive element. For

example, the quaver-chords in the central section of ‘Am Feierabend’ were

not only crystal-clear and light, but were followed by a distinct silence,

the short rest evoking the slowing of the mill-wheel and the young man’s

growing weariness, but also his unsettling self-doubts as he wonders if he

can inspire love in the girl who has bewitched him. Similarly, at the close

of ‘Danksagung an den Bach’, the gentle diminution of the postlude, with

its delicate ornamentation, acquired an intimate, almost confessional,

quality.

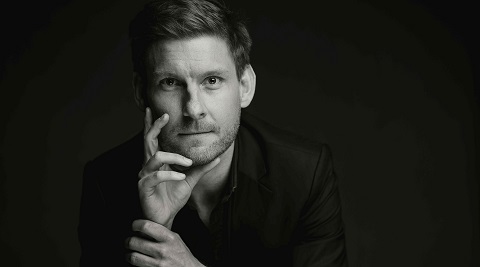

Kristian Bezuidenhout (fortepiano). Photo credit: Marco Borggreve.

Kristian Bezuidenhout (fortepiano). Photo credit: Marco Borggreve.

And, it was a quality that Mark Padmore’s communication of the cycle’s

musical narrative wonderfully sculpted and enhanced. Initially, this miller

was perhaps not quite the carefree adventurer of Müller’s opening poems.

Rather, his purposefulness already seemed tempered by a proclivity for

dreamy detachment, but Padmore’s relaxed, beautifully enunciated

presentation of the text had the effect of entrancingly drawing the

listener into the miller’s psyche. In ‘Danksagung an den Buch’ the tenor

seemed to distinguish the words spoken aloud, to us, and those that are

heard only within his own mind, and the major/minor alternation was

movingly expressive. The floating tenderness of the girl’s sweet ‘good

night’, which the miller dreams into being at the close of ‘Am Feierabend’,

effected a shift in the expressive temperature in the following ‘Der

Neugierige’, the vocal fluency and prevailing ‘simplicity’ suggesting a

growing self-delusion which blossomed in the following ‘Ungeduld’ in

intense assertions of devotion: “Dein is mein Herz, und soll es ewig

bleiben.” (My heart is yours, and shall be forever!)

The uneasy balance of confidence and anxiety dissolved, however, towards

the close of ‘Des Müllers Blumen’ where the spaciousness of the

fortepiano’s compound rhythms and the delicacy of Padmore’s pianissimo intimated the ‘rain of tears’ to come, in

‘Tränenregen’. Here, again, the move to the minor key in the closing verse,

allied with a carefully crafted dynamic rise and retreat, powerfully

communicated the miller’s piercing yearning. Such longing was transformed

into the ebullient confidence of ‘Mein!’, and the tender ecstasy of ‘Pause’

in which Padmore’s sweet head-voice seemed to embody the transfiguring

beauty of the miller’s lute itself, as the breeze brushes gently across its

strings, and also the fragility of the miller’s illusions.

The latter were shattered with the arrival of the hunter. The miller was by

turns defiant and despairing, his defeat by his romantic rival confirmed by

the quasi-reluctance of the fortepiano’s staccato progressions in ‘Die

leibe Farbe’ and Padmore’s ghostly, dissolving lament: “Die Heide, die

heiss ich die Liebesnot,/ Mein Schatz hat’s Jagen so gern.” (I call the

heath Love’s Anguish, my love’s so fond of hunting.) The ‘world beyond’

took an ever more inescapable hold. The dynamic alternations and Padmore’s

subtle verbal nuances in ‘Die böse Farbe’ revealed the miller’s fragile

grip on the real, while the fortepiano’s delicate pianissimo

quavers at the start of ‘Trockne Blumen’ seemed to come from ‘elsewhere’.

The exquisite gentleness of the vocal line in the latter made the sudden

forcefulness of the close - again, a telling shift from minor to major key

in the penultimate verse - all the more troubling.

One remembers that it was in 1823 that Schubert contracted syphilis, and

that it was during his hospital stay that year that he composed parts of Die schöne Müllerin. The despair that he expressed in a letter to

a friend, Leopold Kupelwieser, in March 1824 was poignantly evident in

Padmore’s performance: ‘I feel myself to be the most unhappy and wretched

creature in the world. Imagine a man whose health will never be right

again, and who in sheer despair over this ever makes things worse and

worse, instead of better; imagine a man, I say, whose most brilliant hopes

have perished, to whom the happiness of love and friendship have nothing to

offer but pain […] “My peace is gone, my heart is sore, I shall find it

never and nevermore” I may well sing now, for each night, on retiring to

bed, I hope I may not wake again …’

But, Padmore’s lament for what is lost was lifted by the miller’s

acceptance of his mortality and by the brook’s promise of renewal and

eternity: “Rest well, rest well! Close your eyes! Weary wanderer, you are

home.” Despite the melody’s twists of pain, the conversation between the

miller and the brook had a compelling fluency that spoke of the miller’s

undeniable fate. For the final song, ‘Des Baches Wiegenlied’, Padmore moved

to the side of the stage, the emptiness at the centre confirming the

miller’s death, the brook’s lullaby ethereal, beatific, calling from

beyond, ever more distant until a slight warming - “Schlaf’ aus deine

Freude, schlaf’ aus dein Leid!” (Rest from your joy, rest from your

sorrow!”) - confirmed the miller’s peaceful union with nature.

Steinberg’s 1976 article with which this review began was a profile of the

American fortepianist and scholar Malcolm Bilson, who has been one of the

principal evangelists for the renaissance of the instrument. Bilson has

remarked, ‘Perhaps it is wrong to put the instrument before the artist, but

I have begun to feel that it must be done’. Well, perhaps. But this recital

at Wigmore Hall was the occasion of a remarkable unity between the

musicians and their respective instruments, an integration of sound and

sense which I feel privileged to have experienced.

Claire Seymour

Mark Padmore (tenor), Kristian Bezuidenhout (fortepiano)

Wigmore Hall, London; Friday 20th September 2019.