First up is Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice, in neither its 1762

Viennese nor 1774 Parisian manifestations, but rather in Hector Berlioz’s

1866 rearrangement, in which the French composer amalgamated,

re-orchestrated and re-wrote the part of Orpheus for mezzo-soprano

(specifically, for Pauline Viardot-Garcia).

But, in fact, what ENO really offers is not Gluck’s opera, but

director-choreographer Wayne McGregor’s dance-opera. Of course, dance is

integral to Gluck’s opera and aesthetic. One critic at the first

performance of Orpheus praised the dancer-choreographer Gasparo

Angiolini for ‘uniting choreography with the choruses and the story in such

a way as to give the performance an appearance no less splendid than

exemplary’. The visual aspect of the work was no less vital and

the crucial in this regard was the influence of Count Durazzo - ambassador

to the Viennese court, and from 1754 director of the city’s imperial

theatres - in engaging not just the ballet-master Jean-Georges Noverre but

also the scene-painter Giuseppe Quaglio whose designs contributed

substantially to the success of Gluck and librettist Calzibigi’s opera.

Indeed, Gluck’s Orpheus is inherently classical in its fusion of

the musical, linguistic, visual and gestural. The composer’s aim was not so

different from that, one hundred years later, of Nietzsche and Wagner: the

revival of classical Greek tragedy through a synthesis of the arts in

accord with the ancient Greek’s principle of orchestique: the

incorporation of dance and gymnastics into theatre. So, it’s not surprising

that choreographers from Isadora Duncan to Frederick Ashton to Pina Bausch

have been drawn to Gluck’s opera, aiming to visualise the music through

physical movement and bodily gesture.

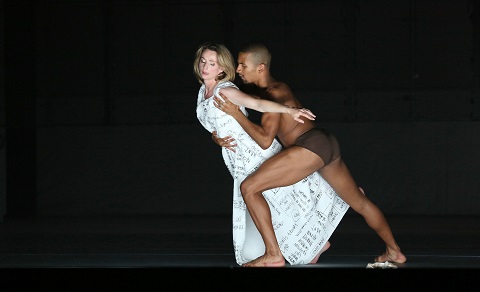

Dancers from Company Wayne McGregor. Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

Dancers from Company Wayne McGregor. Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

Bausch conceived of three dancers’ roles to perform alongside Gluck’s

characters, and McGregor nods in this direction, with two of the fourteen

dancers from Studio Wayne McGregor, Jacob O’Connell and Rebecca

Bassett-Graham, seeming to serve as avatars for Alice Coote’s Orpheus and

Sarah Tynan’s Eurydice respectively. At times, the dancers successfully

evoke the characters’ circumstances and imagined feelings - as when, upon

the death of Eurydice, O’Connell is pinned to the floor by the Furies until

the latter are charmed by Coote’s song and release their captive.

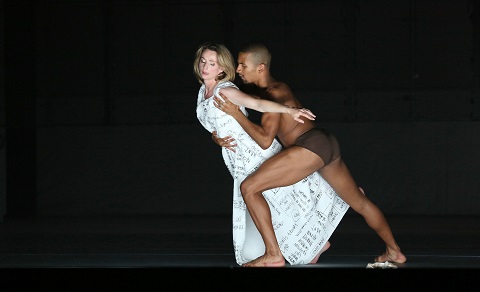

Similarly, the final reunion of the mortals is touchingly expressed in a

physical duet which embraces the singers’ bodily forms too.

Sarah Tynan and Jacob O’Connell. Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

Sarah Tynan and Jacob O’Connell. Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

However, all too often the danced mimes and extended choreographic

sequences do not, to my mind, bring about a union of movement and

music. While McGregor’s choreography is expressive in its own right, and

some of the characters’ thoughts and feelings are exteriorised through

movement in a general way, there seemed to me to be little attempt to give

corporeal form to the emotions and ideas that are expressed by Gluck’s

musical rhythms. Moreover, McGregor seems uninterested in the singers

themselves, despite song being at the heart of the materialisation of the

opera’s ideological foundations. And despite having three terrific

singer-actors with whom to work. There is practically no ‘direction’ of the

cast, while the Chorus - in excellent voice - are consigned to the shadows.

Surely, the latter’s interaction is central to the drama? They are far, far

more than just a disembodied sound? By down-playing the importance of

Gluck’s music and concentrating solely on the physical and the visual,

McGregor undermines the very essence of the opera, shifting our attention

away from the sonic beauty and power of Orpheus’s song.

Moreover, ‘visual’ here refers to light and costume. There is no ‘set’ as

such, though the cavernous black hole of the ENO stage serves as a fitting

representation of hell, even if it doesn’t provide much context or acoustic

support for the singers. Instead, designer Lizzie Clachan relies on Jon

Clark’s lighting and Ben Cullen Williams’ video projections to indicate

situation and mood. So, when Eurydice dies and descends, it’s not so much

to the Underworld that she is heading, rather under-water, as

indicated by the projection of rippling waves above a yellow-tinted glass

tank in which Eurydice is suspended in the manner of a Damien Hirst shark

floating in formaldehyde. The reason for her death is also obscure: she

seems to proffer her arm up willingly to the deathly syringe (snakebite?),

twice, and appears to have left behind a suicide note.

Initially Louise Gray’s costumes are monochrome: Eurydice wears a bridal

gown scrawled with instructions such as ‘Do not look’ (so, why does she get

so upset later when Orpheus does as he’s told?); the dancers sport

skull-embroidered leggings; Coote is forced to don a shapeless sack-dress

graffitied with random words and phrases - ‘deprivation’, ‘tendre amour’

‘underground’. What is the point of such redundant gimmicks?

Dancers from Company Wayne McGregor. Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

Dancers from Company Wayne McGregor. Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

The slide down to Hades is marked by an eye-blinding red-and-green light

show - a sort of sonic-kinetic visualiser - and the dancers spice up their

skimpy costumes with day-glow legwarmers and stripes. Were the Furies

confronting Orpheus with his own sexuality? Asymmetrical clashing primary

colours - and a tender pas de deux for two male dancers - mark the

harmony of the Elysian Fields. Coote and Tynan are left to their own

devices in the final Act, the only directorial-design ‘assistance’ being a

sequence of projected squares and rectangles of analog noise: the fact that

random, flickering dot-pixel patterns of

static

indicate a lack of transmission seemed ironically apt - they are of no

relevance at all to the tragic drama to which the singers are giving voice.

Sarah Tynan (Eurydice) and Alice Coote (Orpheus). Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

Sarah Tynan (Eurydice) and Alice Coote (Orpheus). Photo credit: Donald Cooper.

The three soloists coped gamely with the directorial tabula rasa. It was

announced that Coote was suffering from a viral infection, but while Act 1

felt a little effortful, ‘Che farò senza Euridice’ was intensely

expressive. Gluck himself remarked that ‘Nothing but a change in the mode

of expression is needed to turn my aria “Che farò senza Euridice” into a

dance for marionettes’, and Coote demonstrated the capacity that Gluck

implies a fine singer possesses to make his apparently simple music almost

painfully affecting. Sarah Tynan’s Eurydice burned with credible human

emotions which were delivered with luminosity and strength. As Love, Soraya

Mafi phrased Love’s guidance and entreaties with grace and silkiness.

Conductor Harry Bicket set off at a furious pace - perhaps determined by

choreographic necessities? - and pushed hard throughout, seldom taking time

to bring the details of Berlioz’s orchestration to the fore.

Those who want to see talented dancers perform interesting choreography

will enjoy McGregor’s Orpheus and Eurydice. Those who want to hear Orpheus’s loss, rather than see it, will be less

satisfied.

Claire Seymour

Orpheus - Alice Coote, Eurydice - Sarah Tynan, Love - Soraya Mafi;

Director/Choreographer - Wayne McGregor, Conductor - Harry Bicket,

Rehearsal Director - Odette Hughes, Set Designer - Lizzie Clachan, Costume

Designer - Louise Gray, Lighting Designer - Jon Clark, Video Designer - Ben

Cullen Williams, Translator - Christopher Cowell, Orchestra and Chorus of

English National Opera.

English National Opera, Coliseum, London; Tuesday 1st October

2019.