There are, it’s probably true to say, very few conductors who, as Karl Böhm

once said, dare to conduct the prelude to Tristan und Isolde as

Wagner wrote it. Böhm was specifically referring to Leonard Bernstein,

though he never bothered in any of his performances to take the Bernstein

approach himself. Vladimir Jurowski doesn’t either - though, in parts, his

performance sometimes felt even more oddly phrased. Why observe the first

bar rest, but substantially shorten the second, for example? But it was

possible in Jurowski’s performance to ignore the shortcomings in some of

his more creative moments (the full-beam dash into the climax, for one) and

focus on the searing playing of the London Philharmonic Orchestra. You

heard it first on the ascent of the cellos, and that astonishing sigh -

which here just opened out with breathtaking sadness and pain. The phrasing

of the woodwind, and an oboe which burned like incense and then wilted into

silence. This is music that rides a wave and it can sometimes give the

impression of being uncontrolled. Jurowski - like so many conductors - sees

rapture but little else. What I missed here was the struggle, the

exhaustion, the profound psychological darkness that is in this music as

the climax capitulates into unsettled calmness (I have never forgotten Sir

Colin Davis conducting it just this way). Jurowski’s way with the prelude

might have worked better had we got the Liebestod - as it was, the concert

ending seemed unsatisfactory.

The pairing in the first half of Wagner with seven Richard Strauss songs

was an entirely natural fit. Sarah Wegener, a late replacement for Diana

Damrau, who had clearly struggled with Strauss in New York a few days

earlier, didn’t always feel entirely comfortable in some of the songs - in

a program which remained unchanged (except in order). Wegener’s voice is a

touch darker than Damrau’s, but it is also less quicksilver, less inclined

to favour an agile approach and sometimes struggles with the precision of

her breath control. On the other hand, there is a purity of expressiveness,

a willingness to read deeply into the textual meaning of these songs which

is memorable.

Jurowski applied some dangerously slow tempos to a few of the songs on this

program. Whether Damrau would have tolerated the extremely broad playing in

‘Wiegenlied’ or ‘Morgen’ is debatable; in fact, these were two songs where

Wegener excelled simply because she was able to penetrate the text with

some startling originality and beautiful phrasing. ‘Morgen’, particularly,

in which the voice seems to just appear from a void, was striking for its

exceptional richness of tone, but yet it was as fragile and delicate as the

most eggshell-like of porcelain. Here the widening of the tempo seemed

ideal simply because the song was fragrant with the endlessness it tries to

achieve. Wegener didn’t lack pathos either; it felt like a perfect

miniature of Straussian opulence.

‘Wiegenlied’, too, lived a little dangerously but Wegener was able to

remind us that this is a song about fatherhood and the spirituality of a

mother and child. If the voice strained a little above the stave this was a

sign less of her ability to hit the note and more to simply hold its

length. ‘Das Rosenband’, the first in this cycle on the program, was a

little uneasy in approach - almost sensuous as a reading of the text, with

impeccable phrasing, until that glorious ascent into heavenly ‘Paradise’

which never quite soared as it should.

‘Ständchen’ is rather like a painting, almost Debussyian in its imagery.

Wegener clearly knows how to bring the text to life, how to make that brook

babble, the trees bend, the mystery of moonlight cast a shadow and the

flowers smell of their fragrance. If there was a problem, it was less her

fault and more to do with Jurowski’s unwillingness to give much exigency to

the rhythm - these were orchestral brushstrokes that sometimes felt thickly

rendered.

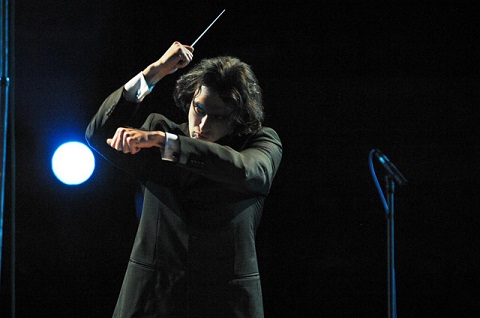

Vladimir Jurowski. Photo credit: Roman Gontcharov.

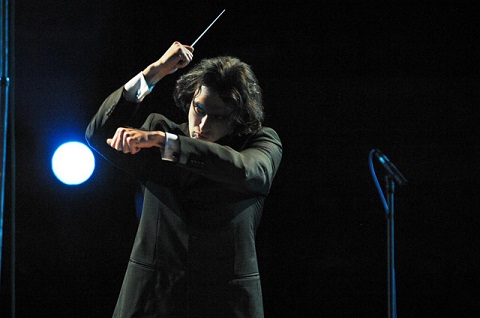

Vladimir Jurowski. Photo credit: Roman Gontcharov.

The original program had ‘Zueignung’ placed in the middle - an odd choice.

In the end, this was the closing song and probably proved the most

controversial. Jurowski’s tempo was extraordinarily slow. This was a

performance less about Wegener and more about the orchestra, the intimacy

suffocated at the expense of some quite outrageous sonorities concentrated

elsewhere. Impassioned and ardent this song might be, but Wegener was

constrained by the amplitude of the orchestra - her final ‘Dank’ so clipped

it simply proved too taxing for her to sustain.

If there is one word to describe Jurowski’s performance of Mahler’s Fifth

Symphony it is innovative. This was one of those Fifths which proved

something of a revelation, controversial though it might have been. It felt

particularly Russian in almost every way - grim, intentionally menacing,

turbulent, brooding, desolate and teetering towards the manic. Often it was

uncomfortable to hear - where one expected it sound Viennese it often found

itself in the grip of wider East European revolution, where there should

have been light there was darkness. There had been an opening Funeral March

which looked back towards Wagner, and where one usually blithely gets

trumpet solos which sound crystalline and polished here they fell like an

executioners axe. The stormy second movement progressed less with the

radiance of ecstasy where it should and more like a requiem for the dead.

When collapse arrived it was like the shattering of stone until what you

were left with was the shell of a totally destroyed edifice in a landscape

that seemed torn apart. Even the Adagietto seemed restless, less a sigh or

love song, and more an uneasy truce between emotions which seemed incapable

of complete expression. There was little joy in the first section of the

Finale - it felt stripped bare, but what a climax! At times, this was a

performance which embraced the darkness of Wagner but looked forward to the

bleakness of Shostakovich.

None of this would have been possible without the exceptional playing of

the London Philharmonic. The strings were like thick black tar, the brass

didn’t shimmer but blasted through the orchestra like a battalion in

combat, flutes and clarinets screamed through their pages as if ripping the

notes off them. Jurowski quite simply gave one of the most manic and

shattering performances of a work which rarely gets heard this way.

Marc Bridle

Sarah Wegener (soprano), Vladimir Jurowski (conductor), London Philharmonic

Orchestra.

Royal Festival Hall, London; Wednesday 13th November 2019.