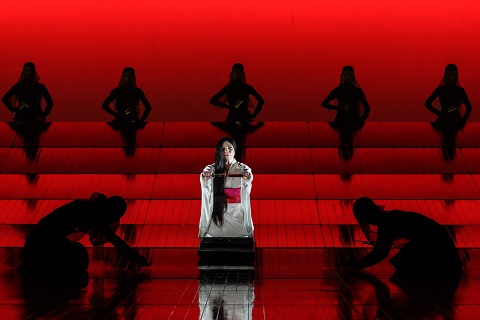

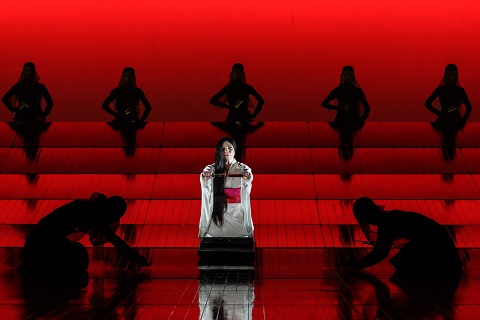

Before a note is played, a geisha’s silhouette emerges into the breath-held

silence, etched against a carmine sky. She glides and floats, her fans

fluttering decorously, glinting in the golden sun. As she raises her arms,

her kimono flickers, as transparent as a butterfly’s veined wing. Her obi

trails behind her, a blood-red bridal train. Scooped up by four dancers,

the sash sculpts curving geometries which twist about the geisha,

confining, restraining. When, in the opera’s final moments, Cio-Cio-San

re-enacts her father’s fate, her wedding obi becomes a silk wound, seeping

and swirling, a bloodless emblem of betrayal and transcendence.

Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Peter Mumford’s lighting pits complementary hues in eye-dazzling

combinations. The ‘visual banquet’ that I admired

in 2013

seemed an even more intensely piercing colour-feast on this occasion. Han

Feng’s costumes heighten the quasi-theatrical strangeness of the

sense-saturating world in which Pinkerton finds himself seduced. Surfeit is

balanced with simplicity, though: the beige shoji that slide noiselessly,

like sleights of hand; the tendrils of cherry blossom that dangle tender

pink against the black night sky.

Natalya Romaniw and Blind Summit Theatre. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Natalya Romaniw and Blind Summit Theatre. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Then, there are the bunraku puppets, brought to life by the conjurer’s

craft of members of Blind Summit Theatre. First time round, I’d found the

puppets too stylised: a representation of the west’s ‘othering’ of the

east. But,

in 2016

I was won over by the truthfulness of the puppets’ uncanny realism, and

here the mime-dance at the start of Act 2 Scene 2 foreshadowing Butterfly’s

suicide was powerful and troubling. It was hard to believe that young

Sorrow, dressed in a US Navy sailor-suit, rushing in stuttering steps to

grasp his mother, tilting his head quizzically, proffering his hand to the

saddened Sharpless, was not real.

Natalya Romaniw. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Natalya Romaniw. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Singing her first Butterfly, Natalya Romaniw made a compelling entrance,

the strong core at the heart of her shining soprano preceding her arrival

at Goro’s marriage-brokering manoeuvres. Perhaps the creamy depths and

heights of Romaniw’s soprano cannot quite capture the innocence of the

fifteen-year-old ingenue, but the Welsh soprano worked hard to convey her

naivety, and of Cio-Cio-San’s honour and pride, feistiness and gentleness,

vivacity and vulnerability, there was no doubt. This Butterfly was bursting

with a passion that she herself could barely know or understand. If I say

that ‘Un bel dì vedremo’ brought I tear to my eye, I am not speaking figuratively. And, the ENO

Orchestra, conducted by Martyn Brabbins, contributed greatly to the emotive

power, so exquisite were the pianissimo gestures and textures. I had been

underwhelmed by Brabbins’ approach in Act 1, but here understatement and

delicacy were magically hypnotic, and thereafter there was more fire in the

orchestral belly.

Dimitri Pittas and Roderick Williams. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Dimitri Pittas and Roderick Williams. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

American tenor Dimitri Pittas, making his ENO debut, was a rather clamorous

Pinkerton, struggling at the top and compensating for lyricism with volume.

The effect was to make Pinkerton, at least initially, even more of a

cardboard villain than usual; though, more effectively, it also made the US

interloper even more of a stranger in this foreign land. By Act 3, this

Pinkerton’s uncomprehending bewilderment was more moving than I had

anticipated.

The other members of the cast were accomplished but did not make much of a

mark, excepting Roderick Williams who, as Sharpless, was brow-beaten by

Pittas’ barking in Act 1, but who sculpted a flesh-and-blood figure of

persuasive empathy and sensitivity in Act 2, his lovely soft baritone

infusing his exchanges with Butterfly with humanising kindness. Stephanie

Windsor-Lewis was a reliable Suzuki but did not convey the fierceness of

her loyalty and love for her mistress. Alasdair Elliott’s well-defined tone

and clean enunciation skilfully captured Goro’s contemptuous condescension.

Keel Watson was a thunderous Bonze, Njabulo Madlala a rather wobbly

Yamadori. Katie Stephenson completed the cast as a somewhat tentative Kate

Pinkerton.

This was Romaniw’s night. And, there surely will be many more such nights.

Madama Butterfly

continues in repertory until 17th April.

Claire Seymour

Cio-Cio San - Natalya Romaniw, Pinkerton - Dimitri Pittas, Sharpless -

Roderick Williams, Suzuki - Stephanie Windsor-Lewis, Goro - Alasdair

Elliott, The Bonze - Keel Watson, Prince Yamadori - Njabulo Madlala, Kate

Pinkerton - Katie Stevenson; Director - Anthony Minghella, Revival Director

- Glen Sheppard, Conductor - Martyn Brabbins, Set Designer - Michael

Levine, Lighting Designer - Peter Mumford, Costume Designer -Han Feng,

Associate Director/Choreographer - Carolyn Choa, Revival Choreographer -

David John, Puppetry - Blind Summit, Chorus and Orchestra of English

National Opera.

English National Opera, London Coliseum; Wednesday 26th February

2020.