October 31, 2007

Oper als Geschäft

It has a principal title: Opera as a business, and a closely related subtitle: Impresarios of the operatic stage in Italy (1860-1900). These two titles are closely related, but also quite different. The first strikes this reviewer as difficult to deal with, since it is the sort of thing that is not that easy to get a handle on. The second could, by itself, have made a fascinating book, especially if it had not been limited to Italy, but to Italian impresarios all over the world, ideally over a somewhat longer time frame, perhaps from Verdi’s first opera (1839) to the beginning of World War I (1914).

This was a period when enterprising Italian companies and their managers not only traveled throughout Italy, but expanded the boundaries of Italian opera all over the civilized world, including the United States, Latin America, the near East (including the Balkans and Russia), as well as the far East, going as far afield as India and Australia. In fact, one company had crossed Siberia, reaching Vladivostok in 1914, but was unable to return home the way they came due to the outbreak of World War I. No problem—they traveled down the coast of China, calling on many South East Asian cities, including some in the Philippines, the then Dutch Indies, Malaya, and India, and eventually winding up in Australia and New Zealand.

Essentially, the author deals with three main impresarios: The Marzi brothers, Luigi Piontelli, and the Corti family, primarily the brothers Cesare and Enrico, their father and their uncle. All of these impresarios traveled extensively, and managed different theatres at different times. But all included La Scala in Milan at one time or another. The Marzis were also prominent in Rovigo, Ravenna, Mantua, Venice and Florence. Piontelli in Venice and Turin, while the Corti’s biggest achievement is cited by the author as being an extended Italian tour with Adelina Patti in 1877-78. They are also listed as heading a “stagione” at the Theatre Italien in Paris in 1883-84

The title also contains an exhaustive index with brief capsule biographies of prominent names, as well as a glossary of Italian terms.

Tom Kaufman

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Oper_als_Geschaft.png

image_description=Oper als Geschäft

product=yes

product_title=Jutta Toelle: Oper als Geschäft

product_by=Baerenreiter, Kassel-Wilhelmshöhe, 2007, 269 pages

product_id=ISBN 3-7618-1365-1

price=EUR 34,95

product_url=http://www.amazon.de/dp/3761813651?tag=operatoday0c-21&camp=1410&creative=6378&linkCode=as1&creativeASIN=3761813651&adid=0PZQKX4ZWCHPB42KK270&

The 17th Bienal of Contemporary Brazilian Music

Opening the festivities was the Fanfarrona (Grand Fanfare) by Tim Rescala, a work which had been commissioned in 2005 to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the opening of the Sala. Surprisingly for a work which one might imagine should have a festive character from the outset, the piece began with no clear character at all, no strong statement, no definitive tone. Gradually the piece took shape, until the concluding section contrasted bits of various familiar marches, etc. for brass, with the more "serious" materials in the string in a Ivesian way. Da Capo (2007) by Marcos Lucas was another work the form of which was difficult to perceive in one hearing - both the gesture of the piece as a whole, and the gestures of the individual moments, seemed undercharacterized, and the final climax took this listener, at least by surprise. The work suffered from weak intonation in the strings. H. Dawid Korenchendler was not heard at the 2005 Bienal, so it was good to hear his strong Sinfonia no. 7 (Sinfonia quasi seria). Korenchendler is revered as a teacher of counterpoint, but his music also reveals a keen sense of humor, evident in the ironic title, and in the gestures of this good-tempered symphony, depicting the visit of a circus to town, a work more easily intelligible both as a whole and in the individual moments. Here once more the intonation of the orchestra was not up to snuff, a fact most painfully apparent in the opening moments for low strings. The Abertura Sinfônica by Rogério Krieger revealed a technically-skilled writer working in a vein that recalled the sound of North America - Copland, perhaps, or a movie score from the 1960s - not innovative, nor Brazilian, but effective. Clearly the most engaging and beautiful work of the evening was Vereda (2003) by Marisa Rezende, a piece with an original voice, one that clearly communicated motion and emotion, and drew on the resources of the orchestra, but through contrast, rather than presenting them all at once. Rezende's writing is a model of clarity, and she achieved a spacious, grand, exalting effect. The concluding orchestral work was The Book of Imaginary Beings, for piano and orchestra, by Eduardo Guimarães Alvares, making effective use of the winds, brass and percussion (particularly the unison slams with the solo piano), and little use of the strings. Interestingly, none of these six works revealed a concern with producing a characteristically Brazilian statement.

The concluding section of the concert, with the orchestra replaced by percussion, was from a different world, and might more effectively have been programmed as a separate concert, with another three such works, since as a single concert the evening would already have been well-filled with six pieces for orchestra. The extremely high quality of performance from this final section also showed up the approximate qualities of the committed but not always convincing renditions from the orchestra. Reflexio (2006), by Marcos di Silva, for speaker, clarinet, cello, and percussion was well-made, but too long for the scant quantity of material used (as Bilbo said "too much better spread over not enough bread"). The concluding pieces well repaid the patience of the listeners who had remained. Dialogues III (2006), by Roseane Yampolschi, was well-made and engaging, with the visible interaction between the percussionists as motives traveled about the stage adding to the listening pleasure. Profusão 5 - Toccata (2007) by Frederick Carrilho closed the evening with a bang, skillfully integrating percussion elements from popular music into a clearly-structured large-scale work. Both here and in the Dialogues the performance of the Dynamo Quartet was world-class, and worthy of a DVD recording. Virtuoso, and extremely enjoyable. Bravo!

After the festive opening of the Bienal on Sunday, Monday’s concert began with a much more intimate tone. First up was Insinuâncias (2006), by Jose Orlando Alves, a work for two percussionists obsessively examining the possibilities of just a few intervals and pitches – tritones and semitones. Alves generates both lyricism and compelling structure from these limited materials. Next was GRLASHODIBZNTMEV (no, I don’t know what it means either) by Andersen Viana for vibraphone and marimba, a quiet, meditative work with indeterminate harmonies. The chamber music which followed, Matérias by Marcelo Chiaretti, for snare drum and piccolo, was the first truly off-putting work of the festival, with pedestrian material from the snares combining with long tones from the piccolo, more a visual than a musical presence, given that the snare drowned out anything in the piccolo’s low to middle range. Memorably bad, but not so bad that it was good. Soprano Doriana Mendes shone in the Diário do trapezista cego by Roberto Victorio, a piece combining a lyrical vocal line with an extremely active and modern idiom for the accompanying guitar. Mendes’ delivered her poetry impeccably, with intonation that was absolutely dead-on. After a not-so-memorable outing for three percussion (Oscuro lume, by Rogério Vasconcelos, highlighting “dark”, i.e., lower and less brilliant instruments), came another particularly rebarbative work, Vol – For Stanley, by Marcos Mesquita, with material of very little interest stretched out to an unforgivable length. Were this a novel, the reader would not persevere beyond the first chapter.

Soprano Mendes was heard in two similarly-scored works, by Fernando Riederer (Campeche no Escuro) and Marcio Steuernagel (À margem oeste deste mar eterno), for soprano, violin, trombone, piano, percussion (Riederer) or soprano, violin, trombone, trumpet, piano, percussion (Steuernagel). The former was much more effective in that the voice’s incantations were contrasted with instrumental interruptions, rather than combined with the ensemble. Mendes’ small but beautifully produced sound was unable to compete with the open-bore trumpet of the Steuernagel, but then few voices could. An ineffective compositional choice. The evening concluded with a lengthy work for piano (Cartas Celestes XIII by Almeida Prado), in which the virtuosity of the performer (Benjamin Cunha Neto) was more impressive than the material, decidedly more earth-bound than its celestial program of stars and galaxies.

Tuesday evening at the Bienal was devoted primarily to electro-acoustic music. The program began with Cancões dos dias vãos XII (Songs of empty days) by L.C. Csekö, who by now is notorious for the quantity of theatrical smoke surrounding his pieces at the various Bienals (I made sure to sit well back from the stage). Csekö’s contribution was a sort of highly-amplified noise-rock for clarinet/bass clarinet, electric guitar, acoustic piano, and percussion, with the performers doing their work in a haze penetrated only by a couple of horizontal beams of light. No details could be perceived, and it seemed that the entire effect would have more convincingly and theatrically carried off by a death-metal band.

The rest of the first half was much more satisfying. Next up was the electroacoustic Mas tenho consciência?....(2004) from Henrique Iwao, a slow-moving stacking of non-equal tempered intervals moving at different rates of speed, producing a rather Bachian effect (mutatis mutandis, of course, in the area of harmony). If Iwao’s work was Baroque in tone, ReCubos v.1.2 (2007) by Marco Campello (also electroacoustic) was almost operatic in tone, with an orchestral breadth, and sounds suggesting brass, woodwinds, and bells against a background which suggested watery depths. Curto Circuito (2007) by Jônatas Manzolli presented three percussionists (wearing miner’s headlamps on a darkened stage) in a sort of neo-primitive idiom, while images suggesting tribal art were projected on a screen behind them. The work received a warm welcome from listeners. Concluding the first half were two exceptionally whimsical works. The first featured percussionist Sergio Freire performing his own music for percussion controller, with a sort of magic wand controlling sounds from a single snare drum, and what I presume were samples activated in real time. Freire’s self-effacing, almost nerdy presence, his motions in controlling the percussion, and the music itself combined for a memorable moment.

Even more out of the ordinary was the percussion quartet by Siri (nom de plume meaning “crab”) which followed, with performers dressed in snorkeling gear seated on stage with plastic containers of water before them, beating on half-immersed pots and pans. Original and amusing.

The second half began with two more electro-acoustic works. First, by Daniel Quaranta, Pelos olhos de quem ve (In the eyes of the beholder), worked with a palette of clanks, thuds and creaks, reminiscent of a transformed piano, moved through a more diffuse moment, and ended abruptly. Tormenta em campos férteis (2006) by Fernando Iazzetta gained momentum slowly, building to percussive rhythms – the counterpoint of different materials heard at the same time from different points in space inside the hall was very effective. Closing the evening was another quasi-political work by Jocy de Oliveira, with a title in Tupi-Guarani (Nherana), which made use of pre-recorded sounds from Brazilian Indians, combined with pseudo-indigenous motives from the live ensemble onstage – oboe, clarinet, cello, electric guitar, and percussion. Seeing the basin of water in front of the oboist, I waited with bated breath until the moment I knew was coming when the instrument would be dunked. Not something you usually do with a wooden instrument of quality. The oboist was also called upon to play two oboes at once. There was the obligatory entrance of the berimbau (no instrument is more evocative of Brazil). And the final gesture…should perhaps remain unrevealed, so as to retain its impact.

Wednesday was a day of torrential rain in Rio de Janeiro, with as much as 15 cm falling, with landslides, tunnels closed, streets flooded, and the government advising car owners to leave them in their garages. By starting time for the fourth program of the 2007 Bienal streets were almost empty, but nevertheless a large number of hardy music-lovers managed to make it downtown. The concert focused once more on electroacoustic works, opening with a programmatic piece referring to the killing of composer Anton Webern by soldier Raymond Bell, after the former had stepped out for a smoke (Raimundo e os sinos (2007), by Marcelo Carneiro de Lima). There were plenty of bell-like tones, but otherwise an ill-informed listener would have no idea of the content. In other words (2005/6), by Bruno Raviaro, for sax and prepared piano, made a strong impression, particularly the cognitive disconnect between the visual of pianist Tatiana Dumas executing a two-armed full smash on the keyboard, and the sound that issued from the instrument. The wild flurry of notes that followed brought piano and saxophone closer than one would have ever imagined. Perhaps the fact that the work was based on a previous improvisation meant that it failed to hold one’s interest for its entire length. Metagestos (2006), by Christine Dignart, was attractive, with a sound world reminiscent of computer music and synthesizers of thirty or forty years ago. One of the most striking works of the festival followed, a piece for soprano and tape by Paulo Guicheney, Anjos são mulheres que escholheram a noite (2006) (Angels are women who have chosen the night), with Doriana Mendes properly celestial, an angelical presence amidst clouds of synthesized sound. The work was dramatic and beautifully paced, with the recorded part supporting, not competing with the soloist.

Estesia (2007), by Rodrigo Avellar de Muniagurria, which closed the first half, combined clarinet harmonics and electroacoustic sounds in a contemplative way, but the shockingly loud noise which concluded the piece (a sort of aural poke in the eye with a sharp stick) revealed another composer who finds it difficult to make a convincing ending in this genre.

The second half began with Lupanar by Marcus Alessi Bittencourt, in which the mechanical sounds made it sound like this particular bordello was all work and no play. The machine noise were punctuated by tenor or baritone register double-reedish beeps and grunts (the male customers?), but the piece went on much, much, much too long.

The Kyrie & Gloria (2004) by Rodrigo Cicchelli Velloso which followed was another of the highlights of the festival, with excellent singing from the chorus Sacra Vox, under the direction of Valeria Mattos. The choral sounds were electronically transformed and echoed, and the combination of choral writing (very effective) and effects was evocative and beautiful.

Closing the concert was an evocation of the sea (Maresia, by Daniel Barreiro), nicely done, almost cinematic in breadth, and a piece neither too brief nor too long, but with an organic shape. The concluding work for heavily-amplified violin and tape (Percussion Study V) was more a piece of theater (carried off with bravura by violinist Mario da Silva) than a work with an intrinsically musical shape.

Thursday’s program returned to more traditional media, with the performing responsibilities divided between the Quarteto Experimental (a clarinet quartet made up of Batista Jr., Walter Jr., Marcelo Ferreira and Ricardo Ferreira), and the strings of the Symphonic Orchestra of UFRJ (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro), under the baton of André Cardoso. The first three works were given to the Quarteto, a group of exceptional musicians playing at the highest level. Prenúncio (de um tormento) (Foreshadowing of a suffering) (2007) by Gustavo Campos Guerreiro began slowly (a mournful glimpse of what is to come), preparing for an outburst of quick patterns in the upper voices while the lower voice continues in its slow motion. A fine work. The extensive Clarinet Quartet (2007) by Thiago Sias revealed an impressively assured and original voice in its writing (particularly for a twenty-five year old at the beginning of his career), exploiting the possibilities of the instruments, with a predominantly lyrical sound. The Criatura no. 1 (2004) by Yahn Wagner (in which the quartet was joined by Waleska Beltrami on French horn) also made a strong impression, particularly the motoric rhythms combining like clockwork, which, along with humorous tone, seemed to this listener to draw on Stravinsky .

The strings of UFRJ then closed the first half with two strongly contrasting works. The first were the Three Miniatures (2006) by Murillo Santos, slight in dimensions, attractive, good-natured, well-made, conservative in idiom. The In extremis, ad extremum (2006) by Roberto Macedo Ribeiro, a passacaglia with moments of beauty, and an obsessive intensity in the masterful stretto and ultimate deconstruction of the material was an anguished crying-out which will remain in the memory.

After intermission came the Tres toques emotivos (2007) by Guilherme Bauer, with a difficult chromatic and contrapuntal idiom which took the strings a bit beyond their technical limits. Canauê, op. 22 (2006) by Dimitri Cervo was considerably more approachable in idiom, beginning with a lyrical theme over string tremolos, and closing with a quicker section combining “Brazilian” rhythms with a minimalist style.

The history and culture of Northeast Brazil then made an appearance with a programmatic piece reflecting the popular literature about outlaws – Cordel no. 1: A saga de Corisco [the story of a famous bandit] by Liduino Pitombeira, the musical idiom balancing between accessibility and modernity, between abstraction and imagery. The program closed with another work, this time explicitly narrative, based on a poem by Euclides da Cunha, in which the strings were joined by baritone Eladio Pérez-González and flutist Eduardo Monteiro, a sort of melodrama in which the vocal part was very much more parlato than sung.

Friday at the Bienal was rather a mixed bag. The evening started with Levante by Rodolfo Vaz Valente, a lengthy piece for clarinet solo, beginning in the lowest register of the instrument and making its way upwards, in a clipped and disjunct idiom, anti-lyrical, one might say, and hardly something one would dance to. Were it a piece of verbiage, you might think of a lengthy disquisition on a rather dry subject. The piece was virtuoso, taking advantage of the prodigious technique of Paulo Sergio Santos, but not at all in-drawing. Next came a song cycle, Vida fu(n)dida, by Calimerio Soares, in which the painstakingly-enunciated utterances of the soloist, Eládio Pérez-González, were at odds with a flightier piano part, and two songs, Homenagens (2007), by Nestor de Hollanda Cavalcanti, celebrating friends of the composer who had passed on, but in a intimate vein making no sense to outsiders, like family pictures from someone else’s family. These were followed by two exceedingly dry pieces (by Rogerio Constante, and by Paulo de Tarso Salles) for guitar, which must have been well-played by the gifted Paulo Pedrassoli, but neither of which held any appeal for these ears, seemingly making a point of avoiding any of the normal seductions of the instrument. The first half closed with two pedestrian choral works, adequately sung by the Brasil Ensemble – UFRJ, but lacking any iota of innovation in style. All in all, eight pieces, with not one generating excitement.

The second half made the trip to the Sala worthwhile. It celebrated the 100th anniversaries of the births of Jose Siqueira (1907-1985) and Camargo Guarnieri (1907-1993), with the Quarteto Radamés Gnattali (Carla Rincón, João Carlos Ferreira, violins, Fernando Thebaldi, viola, Paulo Santoro, cello) performing the Quartet no. 2 of the former, and Quartet no. 3 of the latter. The Siqueira drew heavily on Northeastern folk music, particularly in the stunningly beautiful and lyrical Andante. The Guarnieri was more modern (violently urban) in its outer movements, but also drew on Northeastern idioms in the central heart of the work, the Lento. The playing of the Quarteto in these works brought tears to the eyes. Not to be missed.

My final evening at the 2007 Bienal was Saturday, lamentably, although three more concerts beckoned, but professional responsibilities meant that I needed to fly back to the USA on Sunday. In previous Bienals, the festivities had started on Friday evenings, meaning that fans from outside Rio could fly in, spend two weekends sandwiched around a week of concerts, and get back to work by Monday morning. No such luck this year, and something I consider poor planning by the organizers (of which, more later).

The program began with a work for two pianos (performed with verve by Sara Cohen and Zélia Chueke) – Agua-Forte (2006), by Ricardo Tacuchian, a piece in a surprisingly conservative idiom, with figuration and rhythm quite regular in a free opening section which led to a fugato on what sounded like an “Indian” theme. There were details which recalled, of all people, Gershwin.

Three choral works followed, in performances by the Coral Harte Vocal. Both the modest dimensions and ambitions of the works themselves, and the renditions by the chorus, reinforced my impression that choral music in Brazil is an area susceptible to considerable growth, and one in which achievements are yet below what is the norm for other genres in Brazil, and below the norm for top choruses elsewhere in the world. The chorus, made up of young, seemingly untrained voices, produced a small sound that barely carried to where I was sitting.

The first half ended with a substantial and quite attractive piece for a traditional ensemble, the Quartet 2006 for piano quartet by Ernest Mahle, capably performed by Sara Cohen, Ricardo Amado, José Volker, and Marcelo Salles. The work is predominantly retrospective and lyrical in tone, with a striking middle movement, Andantino cromatico, played sempre pp.

Rather than end this panorama of Brazilian music on a sour note, I will let the first be last, and the last first. The Toccata Metal (2007) for solo cello by Yanto Laitano received a virtuoso performance by Paulo Santoro, but to these ears it was naught but sound and fury signifying nothing. I can’t imagine wanting to hear it again. Does the “metal” from the title refer to “heavy metal”? Hard to say. Ambitious but unsatisfying was Pathos (2006) for a quartet of clarinet, viola, cello and piano by Bruno Angelo, with many unisons perhaps intended to be dramatic, but which chiefly showed that the young players were incapable of playing in tune, particularly the lamentable cello, excruciatingly out in its high register. Ouch!

Far more rewarding were the two works which opened the second half, Celebração (2006) by Maria Helena Rosas Fenandes, quite original in voice and dark in tone, with a religious program, but one which was not usually audible in the music, except for the evocation of animal voices in the opening Cântico das criaturas. Particularly striking was the Paisagem do inverno (Winter Landscape) (2006), by Harry Crowl, beautifully played by Batista Jr., clarinet, Vinicius Amaral, violin, and Luciano Magalhães, piano, evoking first winter storms, and then an a chilly, but more tranquil, calm, with a harmonically static section leading to a long, long, long final adagio, masterfully captured by the trio. Captivating!

Some closing thoughts: each Bienal reveals the richness of contemporary music composition in Brazil, but also brings home to me how little this beautiful music is known internationally. The Bienal should be an opportunity for the country to show the best of what it produces to the world, not simply an opportunity for composers and performers to meet. For the Bienal to fulfill a broader function, it needs to have a firmer organizational and funding base, a base that would allow the festival to be scheduled years, rather than months, in advance, and should make a concerted effort to attract music-lovers from around the world to visit, including the international press. It is shocking how the Brazilian press itself can ignore this important event, with no prior coverage, and almost no reportage of the concerts of the festival. Music is in Brazil is vital – the composers and performers for this festival were almost all in their forties, thirties, twenties – and it communicates, but it needs help from the media to get its message across.

Tom Moore

image=http://www.operatoday.com/villa_lobos.png image_description=Heitor Villa-LobosOctober 30, 2007

MAHLER: Symphony no. 3

Such is the case with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s 2006 concert in which Bernard Haitink conducted Mahler’s Third Symphony on several evenings in October of that year. Taken from performances recorded on 19, 20, and 21 October 2006, this live recording preserves the outstanding association between Haitink and the Chicago Symphony, a relationship that continues through the present season. This first release on the Chicago Symphony’s own label also brings the fine performance to a broader audience with a performance that stands well when compared to other, fine recordings of this challenging work by Mahler.

Because of the expansiveness of the sound involved with this Symphony, the Third is not always readily accessible through recordings. The waves of sound with which the out movements conclude stand in contrast to the delicate and chamber-music-like sonorities of second movement, the Tempo di Menuetto. Likewise, the string textures that dominate the latter movement and the much of the Finale differ in quality from brass timbres of the first movement or the vocal textures in the fifth. The fourth movement poses other challenges, with its subtle accompaniment to the solo female voice that presents the text from Friedrich Nietzche’s Also sprach Zarathustra, “O Mensch!, Gib acht!” The series of contrasts point to a palette of sounds and textures that typifies the organic structure of the work, a composition in which its composer attempted to relate the various levels of existence, from inarticulate nature to human speech and, ultimately, its unity with the Deity expressed here as the apotheosis of love, the force that binds the cosmos within the Schopenhauerian existence.

In expressing the world through the genre of the symphony, Mahler made the symphonic idiom a universe of its own, through the range of ton colors and textures, musical forms, and other elements he united in what is, ultimately, a cyclic work. The challenge for the conductor and the orchestra is to bring out the unity of Mahler’s conception, without allowing its diversity to suggest a disjointed work. Among the memorable recordings of this work are those of Leonard Bernstein, with the New York Philharmonic and also James Levine with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Other historic recordings of this work include Mitroupolos’s relatively early, albeit somewhat truncated recording from the 1950s. In this recording of his recent performances of the work, Haitink demonstrates the command of the score that made his earlier recording of the Third Symphony memorable when he performed it with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Yet this later performance by Haitink retains its own quality. Without comparing this particular performance against the others, listeners will find in this CSO-Resound release a compelling interpretation because of Haitink’s attention to the details of the score. At the same time the finesse of the Orchestra is apparent throughout, with the solo parts evenly precise and expressive. No concerto for orchestra, this work remains has demands of solo performances and soli sections that exceed the kind usually encountered in a conventional symphony. It requires an ensemble as skilled and integrated as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra to approach this score so convincingly, and when as insightful a conductor as Haitink can shape it, the result is memorable.

The vocal element also requires a deft musician, and Michelle De Young is exceptional in this work, and this recording is almost a close-up of her performance, which was more distant when heard from the stage of Symphony Center. Audible, yet not overly present, De Young’s articulate voice and subtle coloring are essential in the sub-structure of movements that lead from the depiction of night, in which she sings, to the contrastingly bright sounds of programmatic angels in the following movement. Those two shorter pieces are a foil for the slow Finale, in which Love is expressed without words in an instrumental piece that is impressive for its majestic and subtly powerful conclusion.

Mahler’s symphonies contain a variety of Scherzos, and the one Mahler composed for this work is notable for its inclusion of an instrumental transformation of one of his settings from Des Knaben Wunderhorn. The solo trumpet – the Posthorn – Mahler scored for the work, is particularly effective in this recording because of its sweet and even sound. Heard live, the sonic distance that occurs in this passage seems greater than it can be rendered in a recording like this. Yet this recording offers a fine representation of the movement, which is also notable for the woodwinds, which demonstrate their remarkably tight ensemble playing. In fact, such playing is evident in the second movement, which is, perhaps, a little faster than some conductors take the movement, but nonetheless effective here.

The structural weight of Mahler’s Third Symphony resides in its two outer movements, with the expansiveness of the first movement counterpoised by the thematic unity of the Finale. A slow movement, like one of the Adagio movements of a symphony by Bruckner or, the dramatic procession of Elsa in Wagner’s opera Lohengrin, the Finale of Mahler’s Third Symphony demands the intensity that Haitink brought to the live performances and which is evident in this recording. Again, the sonic quality of this recording is a facsimile of the live performances, but does not resemble completely the experience of this music in performance when heard within the resonant space of Symphony Hall. Nevertheless, the sound derived from the microphones place above the ensemble captures some details that might have escaped the audiences at the concerts. It is difficult to deny, though, the powerful conclusion that Haitink draws from the Chicago Symphony in the finale sections of the last movement which, in itself, left a lasting impression about the power of this work in the hands of a master conductor. This is an impressive interpretation of Mahler’s monumental Third Symphony, and it should stand well with other fine recordings of this work. As the CD by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra that inaugurates its own label, this fine release bodes well for future recordings that the ensemble will offer.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mahler_3.png

image_description=Gustav Mahler: Symphony no. 3

product=yes

product_title=Gustav Mahler: Symphony no. 3

product_by=Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Michelle De Young, mezzo soprano, Women of the Chicago Symphony Chorus, Chicago Children’s Chorus, Bernard Haitink, conductor.

product_id=CSO Resound 21744 [2CDs]

price=$21.49

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=7537&name_role1=1&comp_id=1799&genre=66&bcorder=195&label_id=9362

Hamburg's Tales Told

I was amply rewarded for the five-hour train trip.

Having “discovered” Mr. Ketelsen as (already) a world-class “Leporello” in the Glimmerglass “Giovanni” (rivaling my memories of Walter Berry), I was next wowed by him in a star-making turn in the little-performed “Maskerade" (Nielsen) at none other than Covent Garden. It was a triumphant tour-de-force that was roundly cheered by that discerning public (and critics). It is no accident that he has repeatedly been invited back for his signature Mozart roles and Escamillo, among others. Happenstance found me next at a Seattle Mozart “Requiem” where, undistracted by stage business and costumes, I luxuriated in his just-plain-gorgeous sound in a memorable “Tuba Miram."

To the opera at hand, then, how were his “four villains"? Well, confirming my previous experiences, they were beautifully sung, the sizable voice steady and responsive, seamless throughout the roles’ rangy demands, capable of great variety and detail, excellent French diction, and all wrapped up in a handsome stage presence. He is one of those treasurable artists that can totally inhabit a role, all the while singing with great beauty and understanding. If he does not have the stock villainous “snarl” that older (or less refined) voices might bring to it, well, all the better as far as I am concerned.

Let’s get all the “happy” news on the table, shall we? Musically, “Les Contes d’Hoffmann” was very fine, indeed. Tenor Giuseppe Filianoti has been singing all over the map, at many major houses including the Met, and he deserves to. This is a well-produced, full-sized lyric instrument with enough heft and point in it to edge into a slightly heavier Fach like this one. He sang with sensitivity and passion, if at times with a slight Italianate “catch” in the voice (okay, okay, he is Italian!). And he is apparently tireless, pouring out searing, balls-to-the-wall phrases and hushed introspective musings alike throughout the evening. Indeed, at opera’s end, he seemed as fresh-voiced as at the start. Committed actor. Good looking. Major talent.

Although soprano Elena Mosuc was announced (with some drama) as indisposed (with three different ladies on hand to spell her if needed), it was hard to tell from her authoritative portrayal of the four heroines. All the coloratura was finely-tuned for “Olympia;” a fuller, warmer voice was summoned for “Antonia;” and the necessary requirements were met for a good embodiment of “Giulietta.” While I personally find the opera better served by three different voice types, a true diva aficionado is always more intrigued by one lady able to encompass all. And that the attractive Ms. Mosuc certainly does, with considerable success.

Ketelsen (Coppelius), Filianoti (Hoffmann) and Surguladze (Nicklausse)

with "Olympia"

Ketelsen (Coppelius), Filianoti (Hoffmann) and Surguladze (Nicklausse)

with "Olympia"

Nino Surguladze as “Nicklausse” displayed a rich, full mezzo which rather surprisingly emitted from a mere slip of a girl; Deborah Humble provided burnished tone for an honorable turn as “Antonia’s Mother;” and tenor Benjamin Hulett had some wonderful comprimario moments in his four roles. Smaller parts were mostly very well taken and the responsive orchestra played with fine style under Emmanuel Plasson (yes, son of “that other Plasson”).

And this pretty much concludes the great news portion of the evening, for the physical production was somewhat a well-intended grab bag.

I am very nearly ready to start a petition to banish “The Mysterious Cube” from the repertoire of Euro-Scenery. Yes, the whole set was a boxy cube, within which (most of the time) a smaller cube resided, which rotated to reveal our leading ladies through an open fourth wall, or as I refer to it: “Diva in a Box.” Sometimes it just played Sit-‘n’-Spin for no good reason. And just when you thought this thing couldn’t be any uglier, dang if they didn’t reveal a yellow interior re-dressed with garish painted posies all over it; or outfitted it with the flopping-est, most hand-print-smeared Mylar mirror panels I ever hope to see. Designer Hartmut Schoerghofer is on the blame line for this creation.

A blue scrim began each act with well-intended but hard-to-see projections, the first being (I think) disembodied hands - or were they condoms? - nope, they must have been hands ‘cause they later “applauded” when the show-within-a-show’s “act” was over. That business over, the set-up seemed that we were in the Kantine of the theatre where Stella was performing. It was awfully trendy for a Kantine, though. In fact if we were to believe the employees’ tee shirts, it was called “La Diva” (get it?). Four TV monitors showed what was going on “on-stage.”

A hip and handsomely clad “Lindorf” arrived with a rolling suitcase of minor importance later. The crowd that populated this space at “intermission" included a mix of opera-goers, cast, and crew. A tortured “Hoffmann” entered with “Nicklausse” dressed as his Girl Friday. It must be said the energetic, dedicated cast was immersed in their assignments, and plunged wholeheartedly into everything that was asked of them by director Christine Mielitz.

But did she have to ask “Hoffmann” to be all bug-eyed and off-putting? Did he have to thrust his pelvis savagely and snap his fingers on his tale of “Kleinzach” so that he looked like a tryout for the “Jets” in a high school production of “West Side Story”? Did the chorus have to jive and weave and bop like White People Dancing Badly? (In a horrifying flashback, the sight reminded me of the terrible Wisconsin wedding dances of my youth. . .Brrrrrrr)

As our disagreeable hero became obsessed with the video-feed of Stella on one of the TV monitors, he took it off its shelf and schlepped it to the prompter’s box. And then something happened that became my metaphor for the whole evening’s staging: the damn’ thing sputtered and unintentionally went blank. Oh, he covered, and turned the face of it away from us, but the ill omen was communicated. . .

Kyle Ketelsen (Dr. Miracle) and Elena Mosuc (Antonia)

Kyle Ketelsen (Dr. Miracle) and Elena Mosuc (Antonia)

There was at first something quite clever in presenting “Olympia” as a “Marilyn” pop icon, and in having “Cochenille” got-up as Michael Jackson, although having the diva as “Madonna” may have been more apropos. This act was by far the most imaginative direction, compromised as it was with gratuitous futzing around by the chorus, and well, way too much of a (pretty) good thing. “Michael” got visually tiring after a very short while, operating the doll with a twinkling remote. As for poor “Marilyn”:

First, she was a dummy seen from the back, seated on a sofa in “The Diva Box;” then as the real soprano, costumed in a pink (make that PINK) form-fitting short-skirted dress with ample bosoms and buttocks. “Hoffmann” became sex-obsessed (perhaps harking back to those pelvic thrusts), leering at these features like a testosterone-driven juvenile. He became absolutely inflamed when “Cochenille” blew into a tube attached to her, thereby inflating her breasts even larger (shades of “Passionella"!). Later, after the introduction of a helium canister on-stage, “Mr. Cube” turned to reveal a reclining Macy’s Parade giant doll, one breast bared, legs spread, ready for action. That “Hoffman” breaks his magic glasses fainting backwards between her thighs onto her belly, made no sense.

“Coppelius” rolled in the carry-on suitcase to reveal the requisite cogs and gears inside, and then mostly lurked in and around the cube in a pony-tailed ball cap. His last say in “dismantling” the doll consisted of blowing its head off with a Kalishnikov. While there was no sound effect, there was a film projection of splattered brains running down the wall that would have made John Carpenter proud. And now an “aside” on Renate Schmitzer’s costumes. . .

Okay, the concept for “Olympia” was rather an MTV-like disco scene, but was it wise to put the entire chorus in lime green, clinging scoop neck tops with big red Rocky Horror lips on the front of each? And annoying “trendy” accoutrements, like the twinkling bows (or was it heels?) on all the chorus girls’ shoes? This is not the sort of thing that looks good on people of a certain age, and let’s face it, 90% of opera choristers are “a certain age.”

Act Two began with a giant Mylar false proscenium flying in, and then with a loud thunk tipping forward to weakly reflect an overhead view of the real pit musicians. Unfortunately, this and a (rather lovely) floating violin distracted from “Nicklausse’s” well-sung air. As visual compensation, she and “Hoffmann” crossed and formed a beautiful, Pieta-like tableau with a white-clad-as-Virgin-Mary “Antonia’s Mother.”

“Antonia,” first seen in a black pants suit, later appeared for her descent into death with slacks traded for a pink skirt (please note: color motif tie-in). “Miracle” arrived in a doctor’s white smock and wonderful “Wiz”-like reflective green glasses , then reappeared in a similar smock that boasted flowers matching the wallpaper. Ditto her father’s look. The sicker she got, the more posies appeared. In fact, this act was most successful “tale” as far as the quite witty costumes.

However, some real oddities included the addition of faux pianos to each outside wall of “The Cube”; a hanging portrait of Mom that just didn’t “read” in the audience, even before “Mother” surprisingly tore the “canvas” out from behind; and “Miracle” performing his evil ministrations to an empty chair, while the doomed “Antonia” looked on from Cube’s edge.

Kyle Ketelsen (Dappertutto) and Giuseppe Filianoti (Hoffmann)

Kyle Ketelsen (Dappertutto) and Giuseppe Filianoti (Hoffmann)

A real plus in this “tale” was “Frantz’s” wacky arietta. I usually squirm through this as the aging character tenor play-acts at “cracking” the high note, and coughs and wheezes a bit, well, you know, embarrassing, right? In this case, young Hulett was a closet ballerina, or cross-dresser, or both (and why not?). As his dance moves gave way to more strip-tease abandon, he revealed himself to be wearing a camisole, and fishnet stockings, and, after holding a leg up high to one side while singing the last bars, he ended in a really decent split to considerable audience approval! No fooling, this was an inspired moment. One I was still relishing all the way up until . . .

“Antonia” died quite unceremoniously at the prompter’s box, next to the ill-fated monitor in fact, and was hurriedly covered up with a black cloth. She was the lucky one, I thought, as Venice was. . .well. . .not pretty.

In fact, it seemed as if the visual and directorial inventiveness, so promising at the start of the real “tales,” just ran out of steam. This was as bleak a “Serenissima” as I have never seen. I am not sure what was supposed to be in “The Diva Box” but it looked like Hernando’s Hideaway gone bad. The chorus members seated on outer sides of the cube seemed to be malcontent-ed street people in rags and tatters. I think. The lighting was so dark it was hard to see. . .chorus. . .principals. . .anything of note.

“Giulietta” herself was got up in a black turban, pants, and jacket over a gold bustier which made her look eerily like “Karen” from “Will and Grace” at a costume party not of her own choosing. “Hoffmann” gave in to the carnal build-up of three (unnatural) Acts and stripped off his shirt, mounting the soprano before rolling on his back and being mounted in return. Mercifully this was mostly masked by the prompter’s box, the dead monitor, and “Antonia’s” still-covered corpse double.

The Box

The Box

There is just so much “cube-lurking” that can be passed off as true direction, and “Dapertutto,” sporting Muslim headgear, was not well served by uninspired blocking. A performer of this caliber has far more to offer dramatically than was asked of him here, although a quite beautifully sung “Scintille, Diamant” was compensation.

This was clearly a bad part of town. As “Nicklausse” looked on in a Hawaiian tourist shirt, “Hoffmann” violently stabbed “Schlemil,” and shortly after, “Giulietta.” No kidding, “Giulietta”! I half expected a “Jose” moment of “Oh, ma Carmen. . .” but instead the Mylar panels on the Cube were a wiggling-jiggling distraction as they hauled “The Diva Box” up and off, and poor “Hoffmann” was left half-naked to ponder that he had caused the demise of all his loves. Or “lusts.” (Okay, okay, excluding “Schlemil”).

Meanwhile, back at the Inn of La Diva, “Dapertutto” (or “Lindorf”. . .or. . .hell, does it even matter now?) symbolically gave “H” the white “Miracle” smock to wear. No longer a sex-obsessed juvenile delinquent, he is back to being an unlikable, ranting jerk of a poet. Having driven “Stella,” “Lindorf” and everyone away, our hero ended the proceedings curled up in a fetal position, white-coated, on two stray chairs down right. Blue scrim in. . .

There were actually any number of good ideas here and enough freshly inventive bits that it was a pity that Ms. Mielick and her design team settled for a profusion of images and movement that became less and less focused. The production could be greatly improved by simply imposing some clarity and discipline in the crowd scenes and, especially, re-considering singer placement on the stage.

Too often, these excellent soloists were far upstage, behind the action, in the dark, singing to the wings, and/or not allowed to take the focus to which they were entitled. Happily, the terrific singing was tremendously satisfying. (I would travel further than Hamburg to hear Mr. Ketelsen again.) Plasson led a brisk, committed reading with all the dramatic consistency that the staging lacked.

Musical glories aside, in the end, just like that hapless prophetic monitor, this “Tales of Hoffman” production promised much, sputtered briefly, and ultimately, went dark.

James Sohre

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Hoffmann_Hamburg1.png image_description=Kyle Ketelsen (Coppelius) and "Olympia" (Hamburg 2007) product=yes product_title=Jacques Offenbach: Les Contes d’HoffmannStaatsoper Hamburg product_by=Above: Kyle Ketelsen (Coppelius) and "Olympia"

All photos courtesy of Staatsoper Hamburg

October 29, 2007

Jean Sibelius: A Film in Two Parts

Written and directed by Christopher Nupen, the result is a solid biographical study of the composer that takes its cue from the various shifts in the reputation of Sibelius, not only within his lifetime, but posthumously. Such a perspective is present from the start, with the narrator’s comments about the changing fortunes of Sibelius’s legacy part of the introduction to the first part of the film.

In presenting this the story of Sibelius’s career, Nupen avoided creating a biopic and, instead, chose the more straightforward approach of illustrating a solidly written narration with iconography associated with the composer as well as performances of his music. The latter include some fine excerpts by the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy, along with vocal music sung by Elisabeth Söderström. To augment the visual palette, Nupen included various natural scenes from the Finnish countryside, and the subtle motion in the landscapes contributes a subtle touch to the images that are otherwise static, albeit quite effective.

At the core of this film is the text that seems driven by the questions about Sibelius’s reputation, and in seeking answers, Nupen addresses not only the biographical details but seeks, at times, to approach the composer’s motivation in certain works. Ultimately the search for answers requires an exploration of both the music and its reception, which results in establishing a context for the success of Sibelius as a composer of both national and international standing. The connections between Sibelius and Finnish nationalism are known popularly through his famous tone poem Finlandia, and Nupen fortunately goes further to discuss this aspect of Sibelius’s career further. The aspiration behind Sibelius’s Violin Concerto and the Fourth Symphony, two works that have, in some respects, fallen short of the expectations behind them. Yet Nupen is keen to establish a context for the careful composition of the Fifth Symphony, which resulted in Sibelius’s enduring contribution to modern symphonic literature.

While the enthusiasm Nupen has for Sibelius’s music is apparent in this film, it never moves toward the kind of hero-worship that biases his work. The balanced and factual treatment of the issue of alcohol in Sibelius’s personal life is part of the narrative, but it becomes neither an excuse for what some may deem failings on the part of the composer nor a sensational topic. Again, the text bears attention for the choice of works, along with the judicious selection of sources from diaries and other primary sources. The reliance on firsthand accounts is selective, and contributes a sense of authenticity that films like this require.

Thus, when Nupen approaches the second part of the film, “Maturity & Silence,” he has already established the composer as an international figure with an individual style, so that he can explore the directions in which the artist could take his musical imagination. Never simplistic, Nupen is clear in the aesthetic success of the Fourth Symphony, without exaggerating the popular appeal and immediate success of the Fifth. The composer’s own comments about his flights of musical imagination at the time he wrote the work are, perhaps, more telling than reviews or other kinds of documents. Yet it is the performance of the music itself in the hands of the Ashkenazy that make the composer’s accomplishments vivid and appealing. The selections are well chosen and as much as some are expected, they are nonetheless welcome in this film. At times, one would want to hear the acclaim of the audience at the conclusion of as bold a statement as the Finale of the Second Symphony. At times the careful superimposition of the narration on the music is nicely balanced.

This is a carefully created film that goes far in describing the life and works of Sibelius. With each of the two segments lasting just over fifty minutes, the length of the film is sufficient to explore the subject in some depth, with time enough for sometimes extended musical examples. Fifty years of Sibelius’s passing in1957, the release of this film serves as a tribute to the composer at a critical anniversary and at the same time asks the question of the composer’s future. While Sibelius’s works are regularly part of symphony programs and recording releases, how does the composer ultimately fit into the various threads that comprise the twentieth century. Is the aspect of nationalism the enduring quality, or is the individual style that inspired the later works ultimately critical to Sibelius’s legacy? Answers to such questions are beyond the scope of the film, but the repeated hearings that Nupen’s efforts will provoke may bring audiences closer to understanding the contributions that Sibelius made in works that have lasted into the early twentieth century. All in all, this is a fine film that serves both its subject and the music well. The DVD is a useful means for making available material like this, with its easily searchable contents and excellent sound.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sibelius.png

image_description=Jean Sibelius: A Film in Two Parts

product=yes

product_title=Jean Sibelius: A Film in Two Parts — The Early Years / Maturity & Silence.

product_by=The Christopher Nupen Films.

product_id=Christopher Nupen Film A05CND [DVD]

price=$26.99

product_url=http://www.amazon.com/dp/B000M2EBWO?tag=operatoday-20&camp=14573&creative=327641&linkCode=as1&creativeASIN=B000M2EBWO&adid=093FSM4AAHQF4Y1GPCN5&

The Endless Scroll

New works by Philip Glass.by Alex Ross [New Yorker, 5 November 2007]

New works by Philip Glass.by Alex Ross [New Yorker, 5 November 2007]

Philip Glass is without a doubt America’s most famous living composer of classical music. In fact, he may be America’s only famous living composer of classical music—the single one who would draw nods of recognition (or irritation) if you were to start waving eight-by-ten glossies of modern-music masters at passersby in Times Square.

Kitsch captures the castle

By Martin Bernheimer [Financial Times, 29 October 2007]

By Martin Bernheimer [Financial Times, 29 October 2007]

Massenet’s Cendrillon is many things – a fragile study in Gallic romanticism, a precarious fusion of fantasy, comedy and melancholy, a sophisticated composition that makes knowing references to Debussy and even Wagner, a sensitive ode to adolescent love. It is not, however, a crass cartoon. One wouldn’t have guessed that on Saturday, when the New York City Opera introduced a popsy new production that it shares with Karlsruhe, Strasbourg and Montreal.

Soprano wins the Bertelsmann Stiftung 12th International Singing Competition

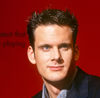

Gütersloh, October 28, 2007. Marina Rebeka (27) from Latvia has won first prize, which carries a cash award of €15,000, at the Bertelsmann Stiftung's 12th NEUE STIMMEN International Singing Competition.The soprano won over the international jury headed by Francisco Araíza with a performance of the arias “Qual fiamma” from the opera “I Pagliacci” by Ruggero Leoncavallo and “È strano, è strano“ from Giuseppe Verdi’s “La Traviata“. Second prize (€10,000) was awarded to the 21-year-old Argentinian bass Fernando Javier Radó, while tenor Diego Torre (27) from Mexico won third prize and €8,000. 1,100 young singers from 66 nations had auditioned in preliminary rounds held around the world, 47 had qualified for the final round in Gütersloh.

Gütersloh, October 28, 2007. Marina Rebeka (27) from Latvia has won first prize, which carries a cash award of €15,000, at the Bertelsmann Stiftung's 12th NEUE STIMMEN International Singing Competition.The soprano won over the international jury headed by Francisco Araíza with a performance of the arias “Qual fiamma” from the opera “I Pagliacci” by Ruggero Leoncavallo and “È strano, è strano“ from Giuseppe Verdi’s “La Traviata“. Second prize (€10,000) was awarded to the 21-year-old Argentinian bass Fernando Javier Radó, while tenor Diego Torre (27) from Mexico won third prize and €8,000. 1,100 young singers from 66 nations had auditioned in preliminary rounds held around the world, 47 had qualified for the final round in Gütersloh.

One Voice for Innocence and Experience

By ANNE MIDGETTE [NY Times, 28 October 2007]

By ANNE MIDGETTE [NY Times, 28 October 2007]

PAMINA is soft, gentle and lovely; the Queen of the Night is angular, cold and brilliant. Yet the German soprano Diana Damrau is to sing both of these roles, the female leads in Mozart’s “Zauberflöte,” at the Metropolitan Opera within two months.

Washington Post Names Interim Chief Critic

By Susan Elliott [MusicalAmerica.com, 27 October 2007]

By Susan Elliott [MusicalAmerica.com, 27 October 2007]

NEW YORK -- Anne Midgette, free-lance classical music critic, feature writer and reporter for The New York Times, is to step in for Tim Page as chief classical music critic at The Washington Post, starting in January. Page is taking a leave of absence to be a visiting professor at the University of Southern California. The Post has been interviewing potential successors for the last several months.

Radio 3 to video stream ENO's Carmen

Chris Tryhorn [Guardian, 26 October 2007]

Chris Tryhorn [Guardian, 26 October 2007]

BBC Radio 3 is to video stream an opera on its website for the first time, offering a performance of the English National Opera's current production of Carmen.

October 28, 2007

DONIZETTI: La Figlia del Reggimento

This brief, light-hearted opera, about a tomboy mascot for a group of soldiers who inspires one love-struck man to enlist just so he can be near her, doesn’t get quite the number of productions as Donizetti’s other comic masterpieces, L’elisir d’Amore and Don Pasquale. At one time, the Fille was more likely to appear as Figlia; in other words, in Italian translation.

That’s the version recorded by Naxos, featuring the orchestra and chorus of the Teatro Marrucino di Chieti. The tuneful charm of Donizetti’s score is irrepressible, but it’s no use pretending that the singing here possesses the personality and appealing tone that stars such as Dessay and Florez bring to the leading roles. The Maria, Maria Costanza Nocentini, produces a metallic, sharp-edged sound that may well carry with distinction in an opera house. As recorded, the effect is not especially appealing. Much the same goes for Giorgio Casciarri’s Tonio. He produces the high Cs at the end of his famous aria; everything before that - and after - feels rough and unshaped. Luciano Motti growls appropriately as Sulpizio. The comic effect of a role like the Marchesa de Berkenfeld carries best in the theater - Milijana Nikolic might be more amusing, seen on stage. The Teatro Marrucino forces are no more than capable.

Fans of the opera probably already have, at the very least, the Sutherland/Pavarotti recording. Anyone looking for a more recent version would be advised to wait until the opera’s latest round of successful productions appears either on CD or DVD. This particular version is no bargain, even at Naxos prices.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Figlia.png image_description=Gaetano Donizetti: La Figlia del Reggimento product=yes product_title=Gaetano Donizetti: La Figlia del Reggimento product_by=Maria, a vivandière: Maria Costanza Nocentini, soprano; Tonio, a young Tyrolean: Giorgio Casciarri, tenor; Sulpizio, a sergeant of the 11th regiment: Luciano Miotto, bass; La Marchesa de Berkenfeld: Milijana Nikolic, mezzo-soprano; Ortensio, major-domo of the Marchesa: Eugenio Leggiadri-Gallani, bass; Un Caporale (A Corporal): Arturo Cauli, bass; La Duchessa (The Duchess of Crackentorp): Giulia Martella, mezzo-soprano; Un Paesano (A Peasant): Franco Becconi, tenor; Un Notaio (A Notary): Alessandro Pento, tenor; Orchestra e Coro del Teatro Marrucino di Chieti, Marzio Conti (cond.). product_id=Naxos CD 8.660161-62 price=$11.98 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=3144&name_role1=1&comp_id=900&genre=33&bcorder=195&label_id=19The Magic Flute — English National Opera

Despite rumours to the contrary, English National Opera’s advertising material claims that this 12th revival of Nicholas Hytner’s popular production of ‘ The Magic Flute’ will be the last. Though it’s arguably better to get rid of a production in its prime rather than when it’s been done to death, it will be a sad loss. The staging has been popular with all sectors of ENO’s audience, as a result of its balance, clarity, wit and visual beauty. This staging more than any other has given me continual pause for thought over the years, leading me to better understanding of the piece.

The ‘ serious’ characters are well-rounded and balanced; after all, they are all supposed to be in some way human. The Queen of the Night is drawn in particularly fine detail; she believes that she’s acting for the good, or why would she afford Tamino the protection of the flute and the guidance of the three boys? Heather Buck’s threatening coloratura was like an explosion of simmering anger and frustration on top of a soft, warm-hued centre, not an all-guns-blazing outpouring of evil. Sarastro, too, has something to learn; as he gets to know Pamina better, he loses arrogance that he never knew he had, and comes to respect a woman as an equal.

Andrew Kennedy was a noble Tamino with lovely tone, though his oddly distorted vowel sounds are becoming increasingly irritating. Sarah-Jane Davies matched him well as Pamina, singing a beautifully poised ‘Ach, ich fühls’ (‘Now I know that love can vanish’). Brindley Sherratt’s Sarastro was perhaps a little weak on the bottom notes, but gave an imposing, centred performance, and Matthew Rose is such a fine Speaker that I long to hear him as Sarastro.

Roderick Williams was a congenial Papageno with considerable charm, delivering Jeremy Sams’s English dialogue in an approximation of a Yorkshire accent. Talking of accents, his disguised Papagena is conventionally played in this production as an elderly Irish tea-lady, which proved a verbal challenge too great for the Swedish soprano Susannah Andersson. Once she was out of ‘ character’ and into the duet, her diction was perfect and she sang very sweetly.

Sarah-Jane Davies (Pamina) / Brindley Sherratt (Sarastro) / Andrew Kennedy (Tamino)

Sarah-Jane Davies (Pamina) / Brindley Sherratt (Sarastro) / Andrew Kennedy (Tamino)

The chorus were on form and Martin André conducted with delicacy and lyricism, but the greatest joy of this production remains the staging. The live doves summoned by Papageno’s pipes; the flood of green light when Tamino is wandering in the woodland; the bears tamed by the flute; the majestic white pillars of the Temple of Wisdom and its glorious interior golden screens with cut-out hieroglyphics; Papageno’s marital nest full of baby birds. Given ENO’s tendency to replace serviceable and popular stagings of core repertoire with misguided ‘concept’ productions, could they not be persuaded to keep this lovely piece of musical theatre for a few seasons longer? I hope so.

Ruth Elleson © 2007

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Magic_Flute_ENO_2007.png image_description= Heather Buck (The Queen of Night) / Andrew Kennedy (Tamino) product=yes product_title=W. A. Mozart: The Magic Flute product_by=English National Opera, 6 October 2007 product_id=Above: Heather Buck (The Queen of Night) / Andrew Kennedy (Tamino)All photos © ENO and Robert Workman

“Apollo e Dafne” — the English Concert at St. Georges, Bristol.

He wrote it at roughly the same time as his first full-blown opera seria were starting to roll off that amazingly fruitful production line which was to dominate the English opera scene for decades, and it has music and drama of the same high quality, even if the quantity is more limited.

It is a delightful, if sobering, tale of out-of-control sexual desire which leads to loss and regret; an everyday tale of country folk set in the misty mythological past where nymphs, shepherds and passing gods wreak havoc in the Arcadian calm. The amorous god Apollo spots a nubile young wood nymph called Dafne. He becomes entranced and then besotted with her and in the end his unwanted advances force her to reject him in the only way left open to her: she turns herself into a sweet-smelling laurel bush, (forever after known to gardeners as “Daphne”) and Apollo is left to rue his heavy-handed technique, singing a heartbroken tribute to his lost love.

Although this cantata can be viewed as a simple morality tale — and most probably was in 1710 — Handel has lavished the full panoply of his skills upon it, though in miniature form compared to his greater vocal works. He actually started writing it, we think, whilst still in Venice where he was both working and networking among the nobility of that great musical centre of the time. The manuscript had to travel with him when he left for a brief sojourn in Hanover which was where it was completed. This break in the compositional timeframe is not noticeable — the arias and recitatives flow smoothly one to the other with all of the young German’s trademark felicity.

A recent national tour by the renowned baroque ensemble The English Concert has put the spotlight back on to Apollo e Dafne and a recent Friday evening saw them performing it as the semi-staged centre piece of an all-Handel programme for an appreciative audience at St. George’s, Brandon Hill, Bristol. This elegant and acoustically-blessed baroque ex-church was the perfect setting for the English Concert’s stylish and alert playing, where both spirit and refinement were found in equal measure. It was particularly interesting to see the band directed not from the violin, but from the fine baroque oboe of Alfredo Bernardini, who has both worked with some of the best period ensembles in the world, and he brought a touch of Italian musical fire to proceedings as he stood and played his instrument with astounding virtuosity in both the two concerti grossi (No 2 in B flat, and No 3 in G) and a shorter cantata for solo soprano “Ah crudel nel pianto mio”.

This lament was plangently sung by visiting Spanish soprano Nuria Rial, who has an ideal voice for this kind of work — clear, limpid and quite white in tone — and she gave a polished if perhaps musically unadventurous reading of it. What was needed was an injection of Italian brio — and we got it with the entrance of Fulvio Bettini as the importuning god Apollo in the main vocal work of the evening. Bettini is an experienced singer of not only Handel’s meaty baritone roles, but also of the earlier Italian masters such as Monteverdi, and his stage credits go from that period right through to Ravel, Weill and Glass. This kind of theatrical experience showed in his robust performance — his characterisation had a 360 degree aspect and his rich middle and lower range was used to the full, expressing not only the god’s passion, but also his frustration and almost comic exasperation with his unwilling beloved. His final aria, when he mourns his vanished love, “Cara pianta, co'miei pianti” revealed a matching ability with legato line. Nuria Rial was a most believable young wood nymph and her desperation and unease was effectively captured by some stylish and elegant singing with neat ornamentation, most noticeably in the lovely aria “Felicissima quest’alma” where her tone was entrancing. The two singers combined gracefully in the final duetto “Deh, lascia addolcire”.

Sue Loder © 2007

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Apollo_e_dafne.png image_description=Apollo e Dafne product=yes product_title=G. F. Handel: Apollo e Dafne product_by=The English Concert at St. Georges, Bristol.SHOSTAKOVICH: Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

The negative spiral of evil at the core of Shakespeare’s drama inspired Leskov to retell the story in prose for Russian readers of the nineteenth century and it, in turn, became the basis of the libretto by Alexander Preis Shostakovich, who gave it a contemporary setting. In telling the story of Katerina Ismailova, Shostakovich portrayed the woman, his Lady Macbeth, with perhaps more sympathy than his nineteenth-century predecessor. The comments by Shostakovich quoted in the notes that accompany this DVD give a concise statement of his intentions:

Leskov finds no moral or psychological justification for murder. I [Shostakovich], however have portrayed Katerina Ismailov as a strong, talented and beautiful woman who succumbs to the bleak surrounds of a Russia populated by merchants and serfs. For Leskov, she is a murderess; I depict her as a complex and tragic character. She is a loving woman, a deeply sensitive woman, by no means without feeling. . . .

In this opera the dissonant idiom Shostakovich used is effective as a sonic foundation for the passionate, if angular, vocal lines. The sometimes harsh orchestral accompaniments not only support the vocal lines, but also offer cues to the audience about the emotional pitch of the scenes, and the sensitive conductor Mariss Jansons offers a perceptive reading of this score. By no means an simple work. Jansons is clear in his interpretations, which offers a clear shape in each scene. At the same time the staging of Martin Kušej offers an appropriate foil for the story, with its outline-like structures of glass and metal that support the work. This DVD is based on the televised version of that staging, which Thomas Grimm directed for film. As a filmed opera, it preserves the sense of being on stage, yet reproduces some of the necessarily intimate blocking for some scenes, with close-ups that would be difficult to capture from a live performance of the work.

The staging itself is realistic and sometimes brutal in depicting murder or sexual longing, thus bringing out further the modernist aspects of Shostakovich’s work. As Kušej is quoted in the booklet that accompanies the DVD, “Orgasm and murder are two diametrically opposed poles, two extreme amplitudes of love and hate, the two fundamental relationships between human beings. This climactic and yet unfathomably deep essence of human behavior is the linchpin of my production. . . .” On this basis, the production brings out the sometimes primal striving of characters to survive both the situations in which they find themselves and also their or drives. Such a perspective is, perhaps, what makes the heroine Katerina intriguing, and Eva-Maria Westbroek succeeds in depicting the character as someone who is at once victim and perpetrator. She is the match for Sergei, whom Christopher Ventris plays convincingly. Early in the opera, a member of the crowd warns that Sergei is troublesome, but that does not deter Katerina in her liaison with him. It is too simple to make Sergei the scapegoat for Katerina’s actions. He is, rather, the enabler, whose passion for Katerina is at the root of her fateful response to her father-in-law’s discovery of their affair.

In performing their roles, the two principals display a command of the music and its nuances. Westbroek is as compelling in her solo numbers as she is when her entrance heightens the ensemble numbers. As much as the performance requires physicality, her voice matches those demands well, and remains inviting and vibrant. Ventris, whose own presence balances that of Westbroek, is equally adept at the role of Sergei, whose brutality is convincingly offputting. Yet his singing is, on the contrary, what makes Ventris’s Sergei memorable.

The chorus serves a actor and commentator, and the members of the Netherland Opera offer a vivid sense of the crowds when necessary. The involvement of the crowd in the sexual attack is stark, and the staging stops short of being graphic. Yet the rendering of Sergei’s liaison with Katerina benefits from the stop-action clips of the performers at various angles that suggests, rather than tells. As such, the stage action balances the musical content without overwhelming it.

Beyond the sensuality associated with Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the opera conveys a sense of the starkness that affects the characters in different ways. In interpreting the score Jansons is sensitive to that aspect of the music and maintains the intensity throughout the performance. This, in turn, drives the work to its conclusion, which is at once fitting and tragic.

This is a powerful production that makes available on video a fine production of the opera by performers who know the work well. The first two acts fill the first disc, with the third on the second. In fact, the latter contains a documentary about the film by Reiner Moritz, which offers some details about the production and the film itself. Recorded in 2006, this recent release is an impressive contribution to opera on DVD, and serves Shostakovich’s work well.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lady_Macbeth.png

image_description=Dmitri Shostakovich: Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

product=yes

product_title=Dmitri Shostakovich: Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

product_by=Vladimir Vaneev, Lani Poulson, Carol Wilson, Eva-Maria Westbroek, L'udovit Ludha, Christopher Ventris Mariss Jansons, conductor, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Netherlands Opera Chorus.

product_id=Opus Arte OA0965D [2DVDs]

price=$39.98

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=11167&name_role1=1&comp_id=10944&genre=33&bcorder=195&label_id=4585

WAGNER: Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

Music composed by Richard Wagner. Libretto by the composer.

First Performance: 21 June 1868, Königliches Hof- und Nationaltheater, Munich

| Principal Roles: | |||

| Hans Sachs, cobbler | bass-baritone | ||

| Veit Pogner, goldsmith | } | bass | |

| Kunz Vogelgesang, furrier | } | tenor | |

| Konrad Nachtigal, tinsmith | } | bass | |

| Sixtus Beckmesser, town clerk | } | bass | |

| Fritz Kothner, baker | } | Mastersingers | bass |

| Balthasar Zorn, pewterer | } | tenor | |

| Ulrich Eisslinger, grocer | } | tenor | |

| Augustin Moser, tailor | } | tenor | |

| Hermann Ortel soapmaker | } | bass | |

| Hans Schwarz, stocking weaver | } | bass | |

| Hans Foltz, coppersmith | bass | ||

| Walther von Stolzing, a young knight from Franconia |

tenor | ||

| David, Sach’s apprentice | tenor | ||

| Eva, Pogner’s daughter | soprano | ||

| Magdalene, Eva’s nurse | soprano | ||

| A Nightwatchman | bass |

Setting: 16th Century Nürnberg (Northern Bavaria [Nordbayern])

Synopsis:

Act I

Inside the church of St Katherine.

Walther von Stolzing, a young nobleman, has just come to Nuremberg and fallen in love with Eva, the daughter of Pogner, a rich goldsmith and mastersinger, one of the most important men of the town. After the church service Eva contrives a few minutes with Walther to explain, in answer to his eager questions, that, although she loves him, she is not free to marry. Her father has decided to offer her hand to the winner of a mastersinging contest to be held the next day, for the festival of St John, Midsummer's Day.

Eva's maid and companion, Magdalena, arranges for her sweetheart, the apprentice David, to prepare Walther for the contest, since only mastersingers are eligible to compete. David is horrified to discover that Walther knows nothing at all about the art of mastersinging and that he hopes to reach in one day a stage which requires years of painful study - such as he is undergoing himself as he studies singing as well as shoemaking under Hans Sachs, the greatest of the mastersingers.

Other apprentices are meanwhile arranging the church for a singing test. The mastersingers begin to arrive. First are Pogner and Beckmesser, the town clerk who wants to marry Eva and is trying to urge her father to put in a good word for him. Walther takes Pogner aside and explains that he wants to join the mastersingers guild. Beckmesser eyes him off suspiciously.

When the meeting begins Pogner announces that he intends to give his daughter and her dowry as a prize in the festival song contest. Sachs suggests that the people ought to have some say in the judging, since the contest is to be public, An argument develops between Sachs and Beckmesser,who clearly regards Sachs, a widower, as a rival for Eva's hand. Sachsenrages him by answering that they are both too old for a young girl. Pogner then presents Walther as a candidate for the guild. To prove his suitability he has to sing a song but is failed by Beckmesser, who acts as examiner.

Sachs defends the song and accuses Beckmesser of not being objective, but the other masters also reject the song, finding it too free and not in accordance with the strict rules of their craft. In the ensuing argument Beckmesser complains that Sachs should spend less time on poetry and more on the pair of shoes he has ordered for the next day.

Walther, failed in the test, leaves the church angrily.

Act II

A street between the houses of Pogner and Hans Sachs, the evening of the same day.

Eva, having learned of Walther's failure to become a master, goes along to Sachs to find out the full story. He, still reflecting on the strange beauty of Walther's song, tests Eva's feelings. She responds so hotly to his disparaging remarks about Walther that he realises she loves him. He is now able to plan how to help the lovers.

When Walther comes along to find Eva he is still very angry with the masters and persuades Eva to elope with him.

She goes inside to change clothes with Magdalena, so that she can escape unnoticed and also so that Magdalena can take her place at the window to listen to a serenade which Beckmesser is supposed to be singing to her that night.

Walther and Eva wait in the street for a chance to slip away but Sachs,inside his shop, has heard their plans and is determined to stop them from taking such a rash step, so he keeps a light shining across the street so they cannot get past unobserved. When Beckmesser begins his serenade Sachs begins to hammer and sing a vigorous cobbling song. To Beckmesser's objections he agrees to stop singing but points out that he has to keep hammering - to finish the shoes Beckmesser has been complaining about.

After some argument it is agreed that Sachs is to act as marker for Beckmesser's song, only hammering when he makes a mistake. But when Beckmesser sings the hammering is so fast and furious that the shoes are finished before the song.

Then David sees Magdalena at the window and rushes out jealously to attack Beckmesser. People open their windows to see what is going on. Apprentices from rival guilds rush into the street and a general brawl develops, only broken off by the appearance of the night watchman.

Sachs manages to bundle Eva into her own house and pull Walther with him into his house just as they are on the point of running away in the confusion.

Act III

Inside Sachs' workshop, the next morning.

Hans Sachs is in a reflective mood, thinking of the midsummer madness of the night before, but still eager to help Eva and Walther. Learning that Walther has had a dream he encourages him to make it into a song, teaching as he goes along how to frame it so as not to outrage too violently the mastersingers' rules and writing it down himself as Walther sings it. With the final stanza still uncomposed they go into another room to change their clothes, leaving the song on the bench.

Beckmesser comes in and pockets the song gleefully, thinking it is by Sachs. To his surprise, Sachs does not object when he finds out, but makes him a present of it. He is torn between gratitude, feeling certain that a song by Sachs will win him the prize, and distrust that Sachs has something up his sleeve - as indeed he does, though all Beckmesser's guesses are wide of the mark. He goes off to learn the song.

Eva comes in, ostensibly to complain about her shoes. Walther is inspired by her presence to finish the song, which Sachs, putting his own feelings for Eva aside and satisfied with his matchmaking, pronounces to be a mastersong.Eva and Walther are deeply grateful to him for his help. Sachs calls David and Magdalena in to help celebrate the new song and also promotes David to the status of journeyman, which means that he and Magdalena will be able to get married. They all set off for the festival.

The festival meadow.