August 29, 2008

A Muse for the Masses: Two Operatic Arenas in Review

Some popular fare was indeed provided in the Arena Sferisterio, the mid-19th-century building originally hosting a local variety of the pelota game. That destination accounts for the immoderate length of its 100-meter stage, a tough challenge to directors and set designers. The acoustics are miraculous, anyway, and the seating capacity, after the latest downsizing out of safety reasons, still amounts to a respectable 2,500, second only to Verona’s awe-inspiring 14,000. Yet even such huge venues are regularly sold out for Carmen and Tosca - those typical evergreens for outdoors arenas - as proved this Summer by their competing productions in Macerata and Verona, just days apart.

Ildiko Komlosi as Carmen in Verona (Photo by Tabocchini e Gironella)

Ildiko Komlosi as Carmen in Verona (Photo by Tabocchini e Gironella)

Macerata’s new Carmen marked the debut in opera direction for

the home-child Dante Ferretti, the set designer who scored no less than nine

nominations and two Oscar Prizes from the American Academy (he is currently

collaborating with Martin Scorsese on a film called Shutters Island,

from Dennis Lehane’s novel, due to be released within 2008). Despite his

involvement with Hollywood pageantry, Ferretti devised a minimalist set

drawing from Francoist Spain during the 1930s-40s, as depicted, among others,

by Luís Buñuel’s movies and Ernest Hemingway’s novels. A dusty square,

a humble fountain in cast iron, two period lorries in various degrees of

dilapidation, a few bicycles, two posters announcing a bullfight: that was

nearly all. No colorful dragoons were around, only Guardia Civil

policemen donning their ominous black monteras; therefore, with

handguns instead of sabers, the duel between José and Zuniga was confined to

a soon-aborted drawing. Lilas Pastia’s tavern in Act 2 was portrayed as a

pretentious bordello for the lower middle-class, where whiskey was sipped

instead of manzanilla and stylish French tango danced instead of

flamenco or habanera. Too bad, however, that some

shabbiness cascaded from the stage into the pit, where Carlo Montanaro’s

conducting sounded weak, almost defeatist. The singing cast fared well

overall, with Irina Lungu a sexier and more assertive Micaëla than usually

expected and Nino Surguladze vocally perfect but arguably too demure, even

lady-like, as Carmencita. If both ladies could exchange bodies or voices, as

in Thomas Mann’s The Transposed Heads, it would fare even better.

As a passionate and lightweight Don José, Philippe Do from Vietnam ventured

a high D in his “La fleur”. If not perfect throughout, his unconventional

performance was stimulating. Alexandra Zabala as a warbling Frasquita and

Simone Alberghini an Escamillo of funereal distinction rounded up the

company. To all that, Sergio Rossi’s clever lighting and prima

ballerina Anbeta Toromani from Albania contributed a touch of class.

Toromani’s amazingly long-limbed body seems a display of pinnacles and

acute-angled forms. Whether in a traditional pas de deux or in

modern free style, she can entice with serpentine motions of a very intimate

character, then suddenly whirl through the air like a winged flower.

Carmen in Macerata, start of Act II [left: prima ballerina Anbeta Toromani + right: Nino Surguladze as Carmen] (Photo by Alfredo Tabocchini)

Carmen in Macerata, start of Act II [left: prima ballerina Anbeta Toromani + right: Nino Surguladze as Carmen] (Photo by Alfredo Tabocchini)

At Verona, with Daniel Oren on the podium, Zeffirelli’s Disneyesque reconstruction of Spain after Bizet found a show-stopping protagonist in Ildiko Komlosi. The Hungarian mezzo sang with great precision and feeling: her capricious rubato was compelling for sensualism, as was the stubbornly dark sound of her lower register. Her presence seemed to inhabit the extra-large stage despite the presence of a distant snow-covered Sierra and the terrific overflow of side-action involving children, soldiers, toreadors and hosts of socially-coded extras, flamenco dancers, live animals. I counted no less than five horses and four donkeys of diverse breed and size, whose unplanned contribution to the stage props caused a thrill when Don José, holding a navaja in his hand during the duel scene in Act 3, barely avoided a slippery spot. With the only exceptions of a fresh Elena Mosuc as Micaëla and the bustling participation of El Camborio, a Verona-based company specializing in Spanish folk dance, the rest was just routine. Thumbs down for the male principals, regretfully. Portraying Escamillo, baritone Marco Di Felice lacked the macho appeal of the toreador who would lure Carmen away from Don José. His low pitches wobbled since his very entrance, thus spoiling his Toreador Song and making his appearance among the smugglers rather unmemorable. Early during his performance as Don José, Mario Malagnini showed intonation problems both in the lower and upper registers. Eventually, his voice opened up and acquired firmness during Act 3 (pretty late, indeed), which allowed him to build a respectable finale, when he poured out his murderous passion with some more convincing accents and a correct stabbing technique - i.e. with his knife moving upwards. In the end, the day was saved by Oren’s deftly balanced conducting, flexible enough to keep together the boisterous and the exotic with the lyrical in the overture and the entr’actes, while aptly emphasizing dance rhythms, shivers of tragedy, and even those finely-wrought ensembles (such as the dizzyingly counterpoint-ish quintet “Nous avons en tête une affaire” in Act 2) which easy-going conductors tend to treat as mere showpieces or perfunctory comic relief.

That a first-rate conductor may make the difference also in large arenas, where the patrons are supposedly more interested in lavish stagings and muscular voices, was equally proved true by Daniele Callegari at Macerata. Under his energetic and nuanced baton, the resident ensembles Orchestra Regionale delle Marche and Coro Bellini delivered a fine rendering of Tosca. Tutti bravi in the company, despite a cold start for both Tiziana Caruso in the title-role and Luca Lombardo as Cavaradossi. Besides singing bravely, Riccardo Massi (Spoletta) and Noris Borgogelli (Sciarrone) looked like a consummate duo of rogues, virtually indistinguishable from each other. But the biggest sensation was Claudio Sgura in the role of Scarpia. Still in his early thirties, the Apulia-born baritone couples firm tone, crisp utterance and dark fascination in the way he stares around or dons his silvery costume as the loveliest villain ever since Ruggero Raimondi’s heydays. Is he the next Raimondi, as his fans keep claiming? Time will tell. Massimo Gasparon’s integrated reconstruction of clerical Rome’s architecture and customs, if not faithful to the least detail, was fascinating and duly oppressive. Despite some controversial precedents, Pier Luigi Pizzi’s pupil (and freshly adopted son) seems to have reached the conclusion that, pace many a self-styled directorial genius, there is nothing wrong in trying to meet the librettists’ and the composers’ stipulations for any given opera as to its setting in time and space.

This is certainly the case with Tosca. “In Tosca, history is definitely in the foreground”, declared Hugo de Ana earlier in 2006. “Therefore I wouldn’t feel happy about making the soldiers wear Nazi uniforms, as is the fashion today, because the atmosphere I want to project is that of the early 19th century at war”. His sober statement strikes a dissonant note within the choir of his European colleagues, who usually delight in peppering their productions with dismissive arguments about “trashy [original] dramaturgy”, boring historical background, clumsy librettos, and so on. Actually, the plot of Tosca is firmly embedded in history: June 15, 1800, in the aftermath of Napoleon’s victory at Marengo, and against the backdrop of three extant landmarks in downtown Rome: Sant’Andrea della Valle, Palazzo Farnese and Castel Sant’Angelo. However, De Ana pushes his ‘provocation’ further: “I don’t think [Puccini] wished to convey a particular interpretation of the Church, the Vatican, or to project a negative idea of religion itself. It’s simply there, creating a background to history”. Good news is that, while giving up with fashionable ego-trips, a director needs not abjure his or her creative knack.

Tosca, Act I/ sc 4, in Verona (Photo by Tabocchini e Gironella)

Tosca, Act I/ sc 4, in Verona (Photo by Tabocchini e Gironella)

Being in total control of the Arena production of Tosca, revived this season with ever-growing acclaim, De Ana strikes the winning move by placing on the center-stage a clone of Rome’s Angelo di Castello, an 18th-century bronze statue of the archangel Michael towering on the top of Castel Sant’Angelo. Between the open arms of that gigantic lad from heaven, who is holding a drawn sword in his right hand and a rosary in the left, most of the action develops amidst a turmoil of Correggio, Giotto and Bernini masterpieces, while period artillery shoots scented salvos from the outer wings, and a backdrop resembling a bronze wall opens now and then, displaying faceless bishops (Roger Bacon-style), a jail and more. Without time machines or sundry brainwave, the outcome looks as surrealistic, avant-garde and disturbing as one could wish. As Cavaradossi, Marcelo Alvarez conquered once more through hyperdramatic singing and acting, granting the traditional encore of his climactic “E lucevan le stelle”. China’s Hui He delivered a vibrant Tosca. She lacks neither good looks, nor soft-grained lyrical tones, nor generous utterance, but appeared sometimes at loss with an unwieldy velvet cloak and did not concede an equally sought-for encore for her “Vissi d’arte”. Sensitive conducting from Giuliano Carella and ovations for everybody. Fifteen minutes of roaring applause, stamping and yelling in several languages from an audience of 14,000 suggest that opera can still count as a muse for the masses.

Carlo Vitali

image=http://www.operatoday.com/T-Caruso_Tosca.png image_description=Tiziana Caruso as Tosca [Photo by Alfredo Tabocchini] product=yes product_title=Georges Bizet: CarmenMacerata, Arena Sferisterio, July 31 (new production)

Verona, L’Arena, July 25

Giacomo Puccini: Tosca

Macerata, Arena Sferisterio, August 1st (new production)

Verona, L’Arena, July 24 product_by=Above: Tiziana Caruso as Tosca in Macerata

Photo by Alfredo Tabocchini

Wagnerian Score: Music 10; Drama 1

Despite the sometimes vociferous booing and hooting of “offending” production teams, year after year, show after show, the damn thing still sells out. So, either somebody likes this artistic philosophy, or perhaps hope springs eternal that somehow, sometime, something, no matter how weird, will actually “land” and illuminate a familiar piece with a fresh perspective. Let’s dispatch the bad news up front:

Director Christoph Marthaler’s “take” on Tristan und Isolde was more of a “took.” Or was it that we were being “taken”? Whatever the conjugation, his is a bare bones, stylized, confusing mounting that is quite bereft of engaging theatrical values. Or even sensible story telling of the “conjugation” of two of opera’s most complex and deeply felt characterizations. At least he had his remarkable soloists often iconically singing full front to maximum advantage, although that usually did pretty much negate any relationships developing.

Mr. Marthaler was abetted by the ugliest costume and set designs I ever hope to see from Anna Viebrock. Remember that name. And avoid it if possible. In fairness, she wins awards. She works a lot. But on the basis of this mess of a visually dreary “Konzept,” it beats me why. Act One’s ship deck was more a Bauernhof-as-waiting-room with scattered overstuffed chairs among overturned, well. . .lawn chairs I guess is the best description. The Sailor and Isolde are discovered hidden seated in the comfy seats, and the “open sky” above is hung with gently shifting and sputtering fluorescent light circles as “stars” (one guesses).

The generally murky lighting gradually (finally) gets bright enough to see that our Isolde is really a quite lovely woman, albeit gowned in a drab garment that is unflatteringly belted at the hips. Kurwenal is in a kilt, Brangaene in a plaid skirt and burgundy sweater. A cursing, agitated Isolde angrily overturned all the lawn chairs that were not already downed. Brangaene having subsequently righted them all, Isolde again deliberately put every last blessed one of them on their side when Tristan entered got up in some preppy blue blazer outfit that makes him look, not old, but too old for Buster Brown. Before the Sailor exited, he and Kurwenal faced front at separate upstage locations and played patty-cake in the air as the Sailor sang. (Are you following any of this?)

For Act Two, a layer of institutional walls had been placed under the ersatz farmer’’s courtyard of Act One which had been jacked up one story in the air. The fluorescent circles were back as proper light fixtures (one guesses) and Isolde spent the first part of the act sparring with Brangaenee as she threatened to turn off the lights via modern day wall switches. When she finally plunged the stage into darkness, it took a long. . .long. . .long time before we got enough light restored to see the lovers. The great love duet was mostly played on and around a silly gold Naugahyde double seater center stage, straight out of your doctor’s waiting room, and the only set piece in the entire empty space.

At one point, for no apparent reason, Kurwenal oh-so-slowly wandered the perimeter of the enclosing box set, touching the walls and looking at them with such intense concentration as if to wish to discover something. (Perhaps a cogent staging idea?) Once the pair were interrupted, the odd overhead light started flickering, with only Isolde noticing, daftly lying on her back and pointing at the stuttering fixtures. The stabbing of Tristan with what appeared to be a switchblade was particularly clumsy. And once Mister “T” impaled himself, damn if Melot did not really get into it, and violently stabbed the hell out our hero until he really seemed quite dead. Act Two closed then with Tristan-as-“door- nail.” Hmmmm, where to go with Act Three? How about “nowhere”?

Another layer of walls (“Dungeon”? “Catacomb?”) had been added to the mix so we now had all three unattractive sets on display for the price of one. Tristan was lying in state on a modern hospital bed on a slightly elevated platform, enclosed by a waist high brass railing. Think Lenin’s tomb. In fact, a line of lower-middle class men in work clothes filed past to view it. Servants? Friends? The Grey Line Tour? Who knows?

Kurwenal had aged noticeably, and now doddered around on wobbly legs. And he repeatedly traversed the perimeter of the railing. Oh, and once, in a demented flash-back moment, he played patty-cake with the air again, oh-so-briefly. (“Man, those were the good old days in Act One. Patty cake and potions.”). The fluorescent circles were hanging on bars on the walls now, occasionally flickering and trying to come to life, but really quite out of service. The electric bill had come due.

Oh sure, “T” finally died and “I” finally arrived, although she was attired in a trench coat over slacks and a blouse, and sort of strutted around with her hands in her pockets, not caring about her dead lover all too very much. The other soloists had wandered on, too, and ended up in various stage positions with backs to us, facing the wall like school kids being punished.

The sublime Love Death culminated with Isolde taking Tristan’s place on the hospital bed and pulling the sheet up over her expiring body, leaving us with a final image worthy of “CSI: Singing Victims Unit.” This was shabby, willful, inexcusable stage-craft- without-the-“craft.”

But. . .the ridiculous was thankfully compensated by the sublime, for this was the most persuasive musical performance I have yet heard of this masterpiece. Peter Schneider led a magnificent, expansive, rhapsodic reading with an orchestra that was in festival form. At the top, the elusive opening phrases may have seemed to be a bit fragmentary, more stand-alone than rhythmically connected, but once past those first few bars, there was an inevitably in the unfolding phrasings, and a passionate forward propulsion that never let up.

The love recognition after the potion has been drunk has never moved me more, and the opening bars of Act Three were brutally painful. The covered pit may not be to all tastes. It is true that some sharpness of detail in the winds and, especially, the brass are inevitable, but the gains in terms of a blended sound are significant. I had wished that the brass off stage at the end of Act One had not been prematurely muted by the curtain fall. And while I did find the odd moment when I thought that the estimable maestro might have showed more restraint when his soloists were dipping into lower registers, Mr. Schneider’s was nonetheless a memorable achievement.

And it would be difficult to field a better ensemble of soloists from among current interpreters. It is hard to believe that Swedish soprano Iréne Theorin was making her role debut as Isolde, so vocally persuasive was she. There are other ladies voicing it as well, to be sure, but Ms. Theorin found a good deal more nuance and variety of utterance than any other I have heard. If you could listen to her dramatic understanding and her fearless use of pauses in some some of the brief unaccompanied bars alone, you would immediately know just how much she “gets it.” She can ride the orchestra, 0most usually with thrilling results, but it is her meaningful communication of the text that won me over so totally. I wished sometimes that she would not over-shoot impassioned leaps to pulverizing high notes, but that seems to be standard issue these days. Suffice it to say hers is a remarkable talent.

No less so was her Tristan, Robert Dean Smith. While this is not a weighty sounding voice, it is the clearest, cleanest vocal production of any interpreter in my experience. I never once felt that he was past his limit, and although I don’t think he had any more to give, what he presented was right on the money, bright and focused, and of a good presence in relationship to the band. He, too, invested his lines with meaning and comprehension. His long death scene was solid and varied, far from the more usual “hope-I-make-it-to-the-end” rendition.

Michelle Breedt scored a big success with the public as Brangaene. But while I always enjoy this fine singer, and while she performed it very very well, I wasn’t sure she had completely mastered this curious and demanding role. She was assuredly not helped by the unimaginative direction she was given (or not given). Jukka Rasilainen was just a tremendous “Kurwenal.” His stentorian, emotionally rich declamations in Act Three zinged off the back wall like laser beams. What a horn! Powerful portrayal. Also fine was the orotund and commanding King Marke from veteran bass Robert Holl. Ralf Lukas made the most of Melot’s small role, and the fresh-voice Clemens Bieber did commendable duty as the Sailor.

Given these triumphant musical values, more’s the pity then that the theatrical side of this mounting was so wanting, with Richard Wagner’s concept of Gesamtkunstwerk (“integrated,” or “complete artwork”) little in evidence. How do producers rationalize “integrating” such astounding musical accomplishments with the deplorable visuals on display? How?

We should be thankful that the Festspielhaus is way up the Green Hill, some distance from Wahnfried, Wagner’s final home and resting place. While we had to suffer through Marthaler’s and Viebrock’s distractions, at least we were spared the ultimate distraction of the scraping sound of Richard turning over in his grave.

James Sohre

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tristan_Isolde.png image_description=Tristan & Isolde product=yes product_title=Richard Wagner: Tristan und Isolde product_by= Tristan (Robert Dean Smith), König Marke (Robert Holl), Isolde (Iréne Theorin), Kurwenal (Jukka Rasilainen), Melot (Ralf Lukas), Brangäne (Michelle Breedt), Junger Seemann (Clemens Bieber), Ein Hirt (Arnold Bezuyen), Ein Steuermann (Martin Snell). Conductor: Peter Schneider. Production: Christoph Marthaler. Costumes & Stage Design: Anna Viebrock. Chorus Director: Eberhard FriedrichAugust 26, 2008

Prom 34 — Puccini's Il Tabarro; Rachmaninov's Symphony no. 1

Although it's often labelled as a melodrama, Tabarro is more subtle than that – a study of unfulfilled, rootless people – and even besides the obvious orchestral sound-effects like the boats' horns and out-of-tune barrel-organ, the musical scene-setting has an impressionistic colour palette unmatched anywhere else in Puccini's canon. This strong and richly evocative raw material gives the opera an advantage in holding its own when scenery and costumes are stripped away and the piece is presented in concert form, as it was here.

Lado Ataneli's Michele was a bit stiff – the traditional concert dress of white tie and tails really doesn't encourage dramatic verisimilitude – but if anything this added to his portrayal of a man who has found himself the wrong side of an emotional barrier in his marriage. Barbara Frittoli conveyed youth more readily than the heavier lirico-spinto sopranos conventionally cast as Giorgetta, and she made a beautiful sound, remaining fully in character even when not singing. There was a warmth to her portrayal which gave a real sense of how out of place this young and passionate city girl is in her life of drudgery in the harsh world of the stevedores. Together, their vocal partnership was ideal; Ataneli's baritone had a dry darkness which only blossomed into warmer lyricism during his plea for Giorgetta to spend the evening with him as in days gone by, while at the same moment, Frittoli's expansive lyricism gave way to a colder, harsher delivery.

The Slovakian tenor Miroslav Dvorsky's full-force singing – sometimes to the extent that he cracked fortissimo high notes – had a brittleness which suited the embittered Luigi.

The smaller, 'character' roles were luxuriously cast, with Jane Henschel as Frugola, Barry Banks as Tinca (hamming up the waltz scene for all it was worth) and Alistair Miles as Talpa. The programme notes gave the names in their literal English translations – Ferret, Tench and Mole. Allan Clayton as the Ballad-Seller and Edgaras Montvidas and Katherine Broderick as the young lovers all gave good lyrical value.

Prior to the interval, the curtain-raiser – which, although it is perhaps unfair to refer to it so dismissively, is how it felt – was Rachmaninov's first symphony, a work which the 22-year-old composer considered a disaster at its premiere, and of which he remained deeply critical throughout his life. Here, after some fluffs and ensemble problems at the start of the opening movement, the BBC Philharmonic made a persuasive case for it; it had a propulsive energy and drive, and it is difficult to imagine any of the BBC's other orchestras producing such a forceful and rich brass sound in the cross-rhythmed fanfares of the last movement.

Gianandrea Noseda

Gianandrea Noseda

We had Gianni Schicchi at the Proms in 2004, also paired with a Rachmaninov piece – his opera The Miserly Knight (both performed by Glyndebourne Festival Opera). Is it too much to hope that Suor Angelica – which has never been performed at a Prom – might complete the triptych before too long? Perhaps, knowing the Proms' preoccupation with anniversaries, we will have to wait another ten years until its centenary.

Ruth Elleson © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Barbara-Frittoli.png

image_description=Barbara Frittoli (Photo by Chris Christodoulou courtesy of the BBC)

product=yes

product_title=Prom 34 — Puccini's Il Tabarro; Rachmaninov's Symphony no. 1

product_by=Barbara Frittoli (Giorgetta), Miro Dvorsky (Luigi), Lado Ataneli (Michele), Jane Henschel (La Frugola), Barry Banks (Il Tinca), Alastair Miles (Il Talpa), Allan Clayton (A song-vendor), Katherine Broderick (Young lover), Edgaras Montvidas (Young lover). BBC Singers, BBC Philharmonic, Gianandrea Noseda (cond.)

product_id=Above: Barbara Frittoli (All photos by Chris Christodoulou courtesy of the BBC)

“Ariadne auf Naxos” at Toronto Music Festival

In its third season, the Toronto Music Festival successfully produced Richard Strauss’ bi-parte opera-within-an-opera, Ariadne auf Naxos. Under the brilliant direction of Agnes Grossmann, also the festival’s artistic director, an assembly of talented young performers, and some more experienced ones illuminated the stage of the MacMillan Theatre for a few hours of dramatically exciting and expressively stimulating music.

Ariadne began as a joint project between Strauss and Hofmannsthal. Interestingly, the version that is now performed originated from three separate ideas. As a result, there are two extant versions: Ariadne I, in one act, to be performed after a German version of Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, and Ariadne II, in a prologue and one act. In this version, Hofmannsthal and Strauss combined the Ariadne myth with commedia dell’arte characters, juxtaposed with 18th Century operatic stereotypes.

Although, Ariadne herself was a point of obsession for Hofmannthstal, Strauss was equally focused on Zerbinetta, to whom he attributed a grand scena di coloratura, equitable to the pyrotechnics in Lucia’s Mad Scene. The original cast included Maria Jeritza as Ariadne, and Margarethe Siems as Zerbinetta. Equally enticing, however, is the young composer of the opera-within-the-opera. The Komponist’s intricate text and singing in the prologue is not only telling of Strauss’ personal connection to the character, but also lyrically masterful.

Melinda Delorme (Ariadne)

Melinda Delorme (Ariadne)

The TMF’s production began with a well-effected instrumental opening and

intended musicality on the part of Maestra Grossmann and the National Academy

Orchestra. She delicately controlled the voicing of the orchestra, and

managed dynamic inflections and colorations with ease and precision. The

dynamic thrusts that are elemental in Strauss where well handled and the

orchestral palette was never compromised.

“Lonely Island Resort,” inscribed on large lettering facing the back of the stage, and a resort lobby complete with a front desk, vacationing guests, and a circulating revolving door, set the stage for the prologue. The first scene lent itself to some fine singing by baritone, Gene Wu, who produced good tone and well-inflected accento puro. The diction coach for this production was Adi Braun, whose authentic instruction faired well on the singers. The stage director, Titus Hollweg’s design was brilliant and never boring, in an opera that can sometimes lack if the singing and inflection is not continually affective. This was not the case in this production, however.

After the Major-Domo, portrayed by The Direction, announces that an opera buffa will be performed after Ariadne before the nine o’clock fireworks, the young composer arrives in hope of a last-minute rehearsal. Dramatically performed by young mezzo-soprano, Erica Iris Huang, the Komponist was convincing in his actions and expressiveness. Huang has a golden tone that is equally beautiful in the lower and higher tessitura, however, her intelligent shaping, and use of messa di voce made the Komponist even more expressive and affective to the audience’s sympathies.

After some kafuffles, the Major-Domo rings again to announce that the two operas are to be performed “simultaneously!” Since such a combination would certainly mean several cuts to the score, the Ariadne soprano and tenor argue over cuts to their respective scenes. Soprano, Melinda Delorme and Tenor, Steven Sherwood make their first stage appearances while singing in a recitativo. Steven Sherwood’s diction was sometimes unclear; although his voice has many promising attributes, he tended to struggle with the overall tessitura of the role. Delorme expressed a warm golden-orange hue to her soprano, and although she sang in recitativo, it was evident that there was more to this voice, thus causing greater anticipation for the opera-within-the-opera.

Désirée Till (Zerbinetta)

Désirée Till (Zerbinetta)

To try and resolve the situation, Zerbinetta, portrayed by soprano

Désirée Till, sets out to extract the details of the opera seria

from its author, charming him into compliance while calculating where her

comedians can best intervene. She is at least intrigued, though not remotely

persuaded, by the impassioned metaphysical gloss he puts on the story. Till

has a lovely clear tone in the higher tessitura, as is often the case with

present-day Zerbinette, even though the role is not specifically written for

a soubrette, but for a lyric coloratura soprano. While in North

America we have somehow misconstrued the soubrette as commensurate

to the lyric coloratura, historically, it is not the same. While Till’s

voice is promising, there was a significant lack of legato in a role that was

written to equate to Bel Canto aesthetics and the type of

fioritura produced by those aesthetics. Till’s exuberance and

dramatic aptitude was, however, illuminating and brilliant. One might have

liked to see her “true self” come through more affectively in her

almost-love-duet with the Komponist.

After Zerbinetta’s tender moment with Komponist, Huang took center stage once more, and fashioned some tender moments of passion and intensity. His paean to “holy art music” is enough to touch any artist or music lover in the most intimate way. Although Huang had some more difficult moments here, contending with the orchestral palette in this section, she expressed a most beautiful lower register and some truly lovely sotto voce moments. In a brilliantly directed moment, the Komponist brings the orchestra into the diegesis. While singing of the sacred nature of music, he motions to the music that swells beneath him, gesturing to the orchestra, thus bringing the orchestra out of the typical mode of accompaniment or harmonic scaffold and making it a full-fledged character within the opera.

The opera Ariadne auf Naxos begins with a destroyed set from the prologue, and Ariadne standing on what had been the front desk, complete in a bridal gown and veil; behind her, an uncut wedding cake. A winding, melancholy overture in G-minor, with an allegro of dismay and alarm opens to the stage-within-a-stage. There were some unsteady moments in the tuning of the violins in this overture. Ariadne’s movements are spastic and she expresses a heavy burden. Although Delorme was dramatically interesting, the actions she effected asked for an even broader sense of abandonment. Three nymphs appear, with exquisite costumes, and lament Ariadne’s inconsolable state. Dramatically and vocally apt, Anna Bateman, Ada Balon, and Laura McAlpine gave solid performances. Until this moment, Strauss’ use of the harmonium has been, more or less, a sustaining factor, but he now entrusts piangente harmonies to the instrument.

The comedians appear with wonder at whether they can cheer up Ariadne. Kudos to Christopher Enns, David English, James Baldwin, and Stephen Bell, for their comical acting and competent vocal performances. Ariadne is unaffected by the comedians, and instead begins to recall Theseus-Ariadne in her soliloquy, “Ein schönes war.” Delorme finally demonstrated the instrument that she had given us small-tastes of in the prologue. A magnificent instrument, with spinto dramatic qualities, Delorme has a bright future ahead. Her continual sense of legato and expressive lyrical shaping left the audience excited for this young singer’s future. Although she had some inconsistencies in her sotto voce singing, the full-range of her instrument is tremendous and illuminating. She possesses a secure middle-voice and a very attractive tone.

The comedians are affected by Ariadne’s lament, as is Zerbinetta, who enters to convince Harlequin to try a little philosophical song. Baritone, Neil Aronoff, has a lovely voice and although he had some difficulty in his higher tessitura, he shows much promise and aptitude for lyrical singing. Ariadne, of course, ignores him and continues her elongated lament. The morbidity of her singing causes the comedians to jump into a Biergarten-like quartet with a descant by Zerbinetta, who quickly realizes that this has had no affect on Ariadne.

She sends the comedians away and addresses Ariadne herself, “Grossmächtige Prinzessin!” Zerbinetta tries to rationalize for Ariadne. “Do we not not all want each lover to be once-and-forever?” She recalls her own collection of amorosi in a brilliant coloratura showpiece, complete with recitativo, a couple of ariette, a rondo with variations, and competing flute. While Till was dramatically stimulating, her vocal production, here, was not as secure. She presented some illuminating moments, but by the end seemed a little vocally exhausted, which is understandable considering the difficulty of this scena. Zerbinetta’s music is a technical exercise and although there were moments of inconsistency, the audience warmly applauded in support of this promising young artist.

During Zerbinetta’s performance, Ariadne withdraws into her cave, refusing to listen. Perhaps this was Hofmannsthal and Strauss’ one error. With Ariadne not present, the intended comic friction between genres is not so evident and so the scene becomes an alternation of soprano styles, rather than a confrontation. Zerbinetta’s scena is followed by the comedian’s major scene, which was comically exciting and well performed, leaving only Harlequin to win Zerbinetta’s heart…or favours.

Suddenly, the nymphs appear to announce the arrival of Bacchus. From afar, his heroic tenor is heard, exulting from his escape from the witch-seductress, Circe. Tenor, Steven Sherwood had significant difficulty in this section, and although his voice shows promise, the high tessitura caused much strain and an absent legato. His arrival on-stage was visually spectacular, with a magnificent ocean-liner called the “Dewine,” crashing through the stage-set and illuminating the stage with its gargantuan presence. Bacchus stands in a stationary captain’s suit, from which he eventually steps down, and sings to Ariadne from above. At first, she expects death, but seems to welcome Bacchus tentatively. Bacchus tells Ariadne that he is a god and during their intense duet, she gives herself up to the stranger sent from heaven.

Delorme continued to express her magnificent instrument in the duet, although dramatically it left one aching for more raw passion and attraction between her and Bacchus. Sherwood struggled throughout, but had some vocally beautiful moments. The lover’s voices entwine and raise up to an epiphany in D-flat and the orchestra effects a pompous fortissimo, eloquently manifested by Maestra Grossmann.

The end of the opera brought Ariadne onto Bacchus’ ship and the return of the prologue and opera characters, including the Komponist, who says nothing but moves to express his affections for Zerbinetta, who finally show her true heart in a gesture of reciprocation. Overall, the production was successful and dramatically interesting. Maestra Grossmann kept exquisite balance between the voices and orchestra; one was never an intrusion on the other. In this production, Melinda Delorme and Erica Huang shone as bright Canadian lights with promise for future operatic success.

Mary-Lou Patricia Vetere © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Erica-Iris-Huang.png image_description=Erica Iris Huang product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: Ariadne auf NaxosToronto Music Festival, 14 August 2008 product_by=Ariadne (Melinda Delorme), Bacchus (Steven Sherwood), Komponist (Erica Iris Huang), Zerbinetta (Désirée Till),Musiklehrer (Gene Wu), Harlequin (Neil Aronoff), Brighella/Tanzmeister (Stephen Bell), Scaramuccio/Offizier (Christopher Enns), Truffaldin (David English), Perückenmacher/Lakai (James Baldwin), Najade (Anna Bateman), Echo (Ada Balon), Dryade (Laura McAlpine). National Academy Orchestra, Agnes Grossmann (cond.) product_id=Above: Erica Iris Huang (Komponist)

August 24, 2008

STRAUSS: Die Frau ohne Schatten — Covent Garden 1976

Music composed by Richard Strauss. Libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

First Performance: 10 October 1919, Wiener Staatsoper, Vienna.

| Principal Characters: | |

| Der Kaiser [Emperor] | Tenor |

| Die Kaiserin [Empress] | Soprano |

| Die Amme [Nurse] | Mezzo-Soprano |

| Geisterbote [Spirit Messenger] | Baritone |

| Die Erscheinung eines Jünglings [Apparition of Youth] | Tenor |

| Die Stimme des Falken [Voice of the Falcons] | Soprano |

| Barak der Färber [a dyer] | Bass-Baritone |

| SeinWeib [his wife] | Soprano |

| Der Einäugige [his brother, The One-Eyed] | Bass |

| Der Einarmige [his brother, The One-Armed] | Bass |

| Der Bucklige [his brother, The Hunchback] | Tenor |

Setting: The Emperor’s palace, Barak’s hut, fantastic caves and landscapes

Synopsis:

Act I

The Emperor’s gardens

The Nurse is visited by a Spirit Messenger sent by the Spirit King Keikobad to check whether the Empress has a shadow. The Empress is the daughter of Keikobad, who had given her a magic talisman enabling her to transform herself into any form she chose. It was while in the form of a white gazelle that she was hunted by the Emperor and struck down by his falcon. She regained her human form and they were married, but the talisman carried a curse, which she has forgotten, threatening that her husband will be turned to stone and she will return to her father if she fails to win a shadow, that is, become pregnant.

A year has passed and she has not conceived, as she and the Emperor are so wrapped in one another that they have not sought to produce children. The Messenger grants a delay of three days, but the Emperor tells the Nurse that he will be probably be absent for three days, hunting for his falcon, which had flown off when he wounded it in his anger at its attack on the gazelle/Empress.

The Empress laments her husband’s absence and her inability, since she has lost the talisman, to transform herself again. The lost falcon returns and weeps because, as it tells the Empress, if she casts no shadow, the Emperor must turn to stone. She now remembers that these were the words, carved on the talisman, and asks the nurse how she can obtain a shadow. With apparent reluctance, the Nurse answers that it is possible to buy shadows from mortal beings. Though she paints a grim picture of the world of men, she is unable to resist the Empress’ plea to take her there to find a shadow.

The Dyer’s house

The three deformed brothers of the Dyer are fighting, but when the Dyer’s Wife throws water over them, they turn on her. In answer to her complaints and threat to leave the house, Barak says that it is his responsibility to feed and care for his brothers. She is discontented and blames him for not having made her pregnant. He answers her vituperations calmly and benignly, but does not succeed in soothing her.

The Empress and the Nurse appear, disguised as serving maids, the latter pretending to be amazed at the beauty of the Dyer’s Wife, who is at first angry at this flattery, but becomes intrigued when the Nurse speaks of a bargain by which she can obtain her heart’s desires: if she will renounce her shadow, she will have slaves, fine clothes and many young lovers. The Nurse transforms the poor hut into a rich pavilion, summons slaves to adorn the wife and shows her her reflection in a mirror. She tells the wife that by renouncing the idea of child-bearing, of which she paints a gruesome picture, simply by selling her shadow, the wife will achieve a life of love and luxury. When Barak is heard returning for his supper, his wife says she will refuse to sleep with him, and the Nurse splits the conjugal bed into two parts and summons fish to appear in the pan, from which, strangely, the voices of unborn children beg their mother to let them in.

The wife tells the dyer that he must sleep alone, while her "cousins," who have come to serve her, will sleep at her feet. Although distressed, he takes it philosophically. Nightwatchmen bless the procreative love of husband and wife.

Act II

The Dyer’s House

As soon as the Dyer leaves for the market the next morning the Nurse offers to send a messenger for the Wife’s secret lover. Disconcerted because there is no such person, the wife confesses that she had once looked with interest at a young man she passed in the street. Using her magic arts, the Nurse summons the shape of a young man. The Empress, who had previously been eager to obtain the shadow, is now repelled by the means used to achieve it and distressed by the apparent corruptibility of mankind.

The wife is embarrassed at this granting of wishes she scarcely knew she had. The young man disappears when Barak returns, laden with food and followed by a troop of beggar children, whom he joyfully feeds, along with his brothers. Again he turns away with a mild answer the discontented reproaches of his wife.

The Emperor’s falcon house in a wood

The Emperor has found his lost falcon and followed it to the falcon house. He has received a message from the Empress that she will be spending the three days of his absence there, alone except for the Nurse. But he senses the aura of humanity surrounding his wife. Believing that she has lied to him, he thinks of killing her, but is unable to bring himself to do so and leaves sadly.

The Dyer’s house

Barak is at work and his wife and the Nurse impatiently await his departure. He asks for a drink and the Nurse gives a cup to the Empress who hands it to him. He falls asleep, but his wife is angry when she realises that he has been drugged, and tries to rouse him. She accuses the Nurse of spying out her deepest secrets and putting ideas into her head. Although apparently not averse to the idea of the young lover, she wants nothing to do with the Nurse’s machinations.

Nonetheless the Nurse summons up the young man and the wife seems inclined to listen to his wooing, but suddenly draws back and, assisted by the Empress, shakes Barak awake, blaming him for sleeping and leaving her at the mercy of thieves.

The Emperor’s bedroom in the falcon house

The Empress sleeps restlessly, haunted by the memory of Barak’s eyes, aware that she has sinned against him. She dreams that she sees the Emperor turning to stone, only his eyes crying for help, and blames herself.

The Dyer’s house

Although it is mid-day, darkness is falling. The Nurse realises that powers greater than hers are at work. The Dyer’s Wife finds the house unbearable, and Barak feels weighed down. The Empress, moved by his great humanity, decides to remain among mankind.

The wife tries again to provoke her husband, hinting at the adventures she has been experiencing and finally announcing that she will not have children, having renounced her shadow as a sign of this. As it is seen that she really has lost her shadow, Barak raises a sword to her and she falls at his feet, swearing that she has not sinned against him, only thought about it, but begging him to kill her. The Empress refuses to take the shadow, which has blood on it. A river rises, Barak and his wife are swallowed up by the earth and the Nurse leads the Empress to a boat.

Act III

An underground vault, divided by a wall

Barak and his wife are on different sides of the wall, unable to communicate, each regretting their estrangement.

A rocky terrace

The Empress and the Nurse are carried by a boat to the entrance to a temple, where the Spirit Messenger awaits them. The Nurse tries to resist, but the Empress knows that she is called to judgment by her father. The door leads to the Water of Life. The Nurse warns her against it, but she believes she has to sprinkle the Emperor with it, to save him from turning to stone. Declaring that she now belongs with mankind, she rejects the Nurse and goes through the gate. The Nurse is unable to follow her and vindictively misleads Barak and his wife as they search for one another. She tries to save the Empress from her fate, but is banished to earth and curses Barak and his wife.

The Empress awaits her father’s judgment, resisting the temptation to drink the Water of Life for the same reason as she rejected the shadow, because it has blood in it. She sees her husband turned to stone, but still has the strength to refuse to accept the shadow at the expense of the happiness of others. The spell is broken and the Emperor returns to life and the Empress throws a shadow. The voices of unborn children are heard calling to them.

A beautiful landscape

Barak and his wife can see one another, but they are on the opposite sides of a ravine. Her shadow turns into a golden bridge. Both couples rejoice and look forward to their children.

[Synopsis Source: Opera~Opera]

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/James_King_Kaiser.png image_description=James King as Der Kaiser audio=yes first_audio_name=Richard Strauss: Die Frau ohne SchattenFor best results, use VLC or Winamp. first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Frosch1.m3u product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: Die Frau ohne Schatten product_by=Emperor (James King)

Empress (Heather Harper)

Nurse (Ruth Hesse)

Spirit Messenger (Forbes Robinson)

Voice of the falcons (Eiddwen Harrhy)

Barak’s wife (Helga Dernesch)

Barak (Walter Berry)

One-eyed (William Elvin)

Hunchback (Paul Crook)

One-armed (Raimond Herincx)

Apparition of a youth (Robert Tear)

Royal Opera House, Georg Solti (cond.)

Performance: 5 April 1976, Covent Garden, London

August 21, 2008

Prom 40 – Boulez conducts Janáček

After the revelatory From The House of the Dead in 2007, it will come as no surprise that Boulez has very special insights, which grow from studying what the composer actually wrote, rather than following received wisdom. No artist with integrity can copy, and what there is of tradition in Janáček is of very recent vintage. Boulez’s ideas are shaped by the music itself, in particular the creative explosion of Janáček’s final decade. Significantly, Boulez came to Janáček through reading the score of The Diary of One Who Disappeared, arguably the beginning of that surge of inspiration. The Diary is an extraordinary work. It blends magic, lyricism and explicit sexual menace, complete with otherworldly off stage voices. Like the tenor, Janáček was embarking into the unknown.

With its confident opening fanfare, the Sinfonietta is dramatic. In the Royal Albert Hall it was visually stunning, for the 13 brass players stood up in a row : trumpets and horns catching the light, glowing like gold. Yet what was striking about this performance was how subtly it was achieved. Noise alone doesn’t mean passion. Janáček played down extremes of volume for a reason. This brass was bright and lucid, not brutalist, leading naturally into sweeping “open spaces” heralded by the winds. This piece was written for athletes celebrating the birth of the new Republic, so this clean vernal playing beautifully captured the spirit of optimism. Boulez understood context. The sassy, punchy turns were there like echoes of a military band en fête. Not violent, but impudent and full of joy.

This combined well, with Capriccio, written for a left handed pianist and small ensemble. It’s as playful, lithe as a cat. The mock heroic passages in the second part, and the deadpan downbeat figures throughout were played with warmth: Boulez’s dry humour proved that there’s more to fun in music than belly laughs. Capriccio isn’t heard too often. Perhaps we need to reassess Janáček’s quiet wit.

The Proms specialise in spectaculars like the Glagolitic Mass, with over 200 choristers, a huge orchestra, 4 soloists, and organ. The Royal Albert Hall organ has 9999 pipes, 147 stops and a height of 32 feet. It’s the second biggest in the world. Janáček was himself an organist and would have been thrilled. In a small Moravian church, this Mass would have been claustrophobic, but Janáček, an atheist who knew all about playing in churches, said his cathedral was “the enormous grandeur of mountains beyond which stretched the open sky…the scent of moist forests my incense”. Parallels with Boulez’s teacher Olivier Messiaen are obvious.

Again, Boulez brings insight. With forces like these, any performance is monumental, hence the temptation is to let sheer scale dominate. Instead Boulez maintains clarity, so the complex textures remain bright and clean. Orchestral details count, despite the magnitude of the setting. The four soloists could easily be heard above the tumult, and the massed voices of the choirs were not muddied. Good singing too, especially Fried and O’Neill. In any Mass, there’s a tendency to focus on lush excess : after all the “story” is pretty big. But as Boulez, himself an unbeliever said before the Prom, the composer chose to set the words in ancient Slavonic which few people understood. This creates a sense of distance, allowing the listeners some freedom of imagination. Of course words like “Gospodi” and “Amin” have obvious meaning, but the words are signposts. The action is in the music and how we listen. Janáček is also creating a temporal distance, as if the piece was a throwback to ancient times and ancient communities that had ceased to exist even in his time.

The version used in this Prom was an edition by Paul Wingfield based on the original score, wilder than the more refined edition we’re used to. Boulez responded to this well, sculpting angular blocks of sound, respecting the jagged, wayward rhythms. This was echt Janáček, that old curmudgeon ! The movement for solo organ seemed almost sedate in comparison, but this being the mighty Willits, there was no way it sounded tame.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/janacek_bohm.png image_description=Leoš Janáček by Gustav Böhm, 1926 product=yes product_title=Leoš Janáček: Mša glagolskaja [Glagolitic Mass] product_by=Jean-Efflam Bavourzet (piano), Jeanne-Michèle Charbonnet (soprano), Anna Stéphany (mezzo), Simon O’Neill (tenor), Péter Fried (baritone), Simon Preston (organ) , BBC Symphony Chorus, BBC Symphony Orchestra., London Symphony Chorus, Pierre Boulez (conductor).Royal Albert Hall, London, 14 August 2008

Torre - Torre - Torre

Oh, sure, once before I cooled my heels at Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw while Gergiev pushed that orchestra through some Shostakovich piece or another, imparting his last minute thoughts while we inadvertently watched it all on the closed circuitry meant for late-comers. But that was, well, Gergiev being Gergiev in a one-off, and this was the renowned annual festival dedicated solely to celebrating beloved local son Giacomo Puccini’s operatic output. Plus, the piece had been performed just the week prior. Hey, and at festival prices, shouldn’t they have “had it down” well before curtain time?

Happily, the performance turned out to be quite an unexpected delight, an old-fashioned confection in the very best sense. Nothing ground-breaking, no real once-in-a-lifetime performances, but Edgar was nevertheless solidly sung, handsomely mounted, and unfussily directed. If it smacked a bit (and just a bit) of “instant opera,” say like in the old start-up days of smaller American companies, never you mind. The audience was there to enjoy the show, “mille grazie,” in this season celebrating the 150th anniversary of Giacomo’s birth, and enjoy it they did.

We had reason to celebrate from the git-go, for once we got into the grounds we were able to fully appreciate the new open air theatre that opened just this summer. The raked seats were comfortable enough as these venues go, the sight lines are very good, the open-backed stage (shades of Santa Fe) reveals the lovely lake behind it, the large pit could seemingly fit in a Wagner band, and the public areas are well lit, uncrowded, and accommodating.

Future seasons will probably see some fine tuning of the acoustics, particularly as regards the orchestra. From my seat, the winds seemed muted and occasionally undefined, and the strings just a little dry. Even in this early opus, there was some lush Puccini string work that didn’t soar and throb the way it might have. The brass certainly had ample presence and prominence, although marked by several (mercifully) brief sections of rhythmic imprecision (if only they had had five more minutes of rehearsal!).

Pier Giorgio Morandi conducted very cleanly with excellent stage balance, though sometimes sacrificing the infectious youthful brashness of the score for tidiness of ensemble. At phrase ends here and there he was not always emoting in sync with his soloists, among whom Marco Berti gets pride of place for his consistently well sung title role. Mr. Berti has a true spinto sound, clearly focused and ringing, and he caressed his phrases with insightful musicality and a pleasing sense of Italianate line. Sustained high notes rang out with secure abandon. He is a large man, and was not always flattered by the schmatte-like tunic-’n’-tights outfit, nor by the long tangle of hair, eerily making him look at times like Mama Cass with a mustache. But, “Dio mio,” did he sing well.

He was almost matched in vocal excitement by the dark-hued mezzo of Rossana Rinaldi as “Tigrana.” She not only served up all the fireworks in the writing, but also encompassed highly affecting legato singing. “Tigrana” is a rather improbable dramatic entity, but Ms. Rinaldi got by with a brazen combination of selective elements of “Carmen” and “Jezibaba,” with a nod to Wicked’s Witch en route to “Baba the Turk.” The extensive tenor-mezzo duet that comprises most of Act II was arguably the high point of the night.

I was especially interested in finally hearing Cristina Gallardo-Domas, who has been singing all over the map, most notably in the Met’s much discussed Madama Butterfly. She is a lovely woman; petite, poised, and appealing, and she maintained a star presence throughout. Her pretty lyric voice was capable of some ravishing piano effects above the staff, every bit as good as the kind that Sills and Scotto used to do so remarkably well.

But while those two divas found a way to manufacture the impression of a bit more heft in their instruments, Ms. Gallardo-Domas seemed to be really stretching to meet “Fidelia’s” demands. Perhaps at the Met, with more grateful acoustics (?) she can fill the place, but in this open air theatre she was pushing her smallish tone to the limit, which at times induced an unwelcome wobble on arching lines that came perilously close to sounding like a musical saw. Pity. I suppose she is now on an irrevocable career path of her (and the major houses’) choosing, but I really hope that her lovely and considerable gifts don’t get burned out by spinto roles that are best left to larger voices. We do need her. But as “Manon.” Not as “Manon Lescaut.”

Strapping Luca Salsi was really all one could wish for as “Frank,” possessed of a ringing, easily-produced baritone of fine presence, that was passionately deployed. His famous aria gave much pleasure. The small role of “Gualtiero” was essayed with dignity and a rolling bass by Rafal Siwek, who looked too young, however to be father to “Frank” and “Fidelia.”

The new production featured an appealing and wholly functional set design by internationally-known artist Roger Dean. A large unit on a turntable is first seen as a quasi half-timbered fairy-tale house. The green-tinged roof that sort of puffs out over the gables is a Gaudi-meets-Grimm affair, a fanciful structure that would not be out of place in Munchkin land. The delightful playing space is further defined by moss- and vine-covered stone stairs stage right and left.

The unit revolved to reveal Act II’s love palace get-away, a playful blue-walled, orange- domed fantasy abode of that lust nest monster “Tigrana.” Turning once again, the Act I house had been removed to reveal Act III’s handsome rocky promontory with caves and stairs. It was visually interesting and afforded good levels for such things as the placement of two banks of trumpets for impressive on-stage fanfares. By adjusting and re-dressing the stairs, Dean came up with a very effective look for “Edgar” and gave the Festival an attractive and practical set that will serve the opera very well for years to come.

An amazingly effective lighting design was achieved with nothing but side lighting (save very sparing use of follow spotlights). It is puzzling why the new theatre did not include a lighting batten or two up front, but as of yet, it offers the challenge of getting an even wash and some appropriate effects with the resources at hand, a challenge that was met quite nicely.

Mr. Dean’s daughter Freyja Dean created the costume design. While the attractive garb for the principals (excepting that previously mentioned tunic), the colorful peasant dress, and the appropriate military outfits looked just fine, they seemed a little anonymous, as though they had been picked off the rack at a good rental house. One unfortunately funny costume moment occurred when our tenor tore open his monk’s robe disguise to reveal himself as the very-much-alive “Edgar,” unintentionally framing his generous belly unflatteringly just as “Fidelia” must scream a high note in shock. (Aw c’mon girlfriend, it’s not that big. . .)

Vivien A. Hewitt’s direction told the story clearly, if mostly uninventively. The movement and character interaction wanted specificity, and all soloists seemed to be left to wandering improvisation at times. “Tigrana” in particular had little to do but pace and act endlessly “trapped” when she was apprehended by the mob in Act III. The dumb-show of “Frank” and “Edgar” jousting on stylized rolling horse sculptures in the same act did not so much suggest “Edgar’s” (false) death, as it served to confuse us in an already squishy dramatic through line. The dagger play both on- and off-horseback was some of the least effective and most tentative I have ever encountered this side of a children’s playground. Still, the massive cast was impressively moved on and off with well-considered precision, and the stage pictures were appealing and dramatically informative.

And just how often does one get a chance to see the minor Edgar given such a major treatment with such an honest effort from a talented production team, a first-rate set of principles, and a well-led professional orchestra? Also deserving mention was the full-throated, precise singing from the Festival Chorus under the direction of Stefano Visconti.

The Puccini Festival offered up a very satisfying rendition of the master’s piece, and the partisan audience was still cheering it long after I made my way to the hotel shuttle van. They may be cheering it still.

James Sohre

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Puccini_Edgar.png image_description=Giacomo Puccini product=yes product_title=Giacomo Puccini: Edgar product_by=Edgar (Marco Berti), Fidelia (Cristina Gallardo- Domas), Tigrana (Rossana Rinaldi), Frank (Luca Salsi), Gualtiero (Rafal Siwek). Fondazione Festival Pucciniano. Pier Giorgio Morandi (cond.)August 19, 2008

Prom 18 — L’Incoronazione di Poppea

Richard Jones’s production of Macbeth last year, whose big blocks of set and full-chorus choreography didn’t made it to the Proms, ended up a shell of its former self, and the voices that had sounded impressively powerful in the intimate Sussex theatre were, if not lost, then at least diminished in effect when transferred to the Hall.

The fact that Robert Carsen’s production of L’incoronazione di Poppea was relatively austere to begin with, starting off at Glyndebourne with little more on stage than a big red curtain, meant that it was destined from the start to transfer successfully to the Proms, in a semi-staging by Bruno Ravella.

Alice Coote as Nerone

Alice Coote as Nerone

The central relationship between Nerone and the upwardly-mobile sex kitten Poppea was portrayed quite unconventionally. The two began the opera drunk with lust and longing for one another, but as the drama progressed, it was clear that Nerone was gradually becoming aware that Poppea’s lust for power and position had overtaken any genuine love towards him. His resentment grows to the point that as he promises to make her Empress, he barely stops himself from striking her – and though he still cannot resist her, most of the final duet was sung from opposite sides of the stage, with the two hardly looking at one another. Poppea gets what she wanted, but for Nerone it’s an empty celebration.

As thought-provoking as it was to see their relationship from that angle it isn’t a concept that’s borne out by the music. From the very beginning, we are told in no uncertain terms that it is going to be a victory for Love over both Virtue and Fortune, and at the end the sinuous intertwining lines of ‘Pur ti miro’ are clearly a musical evocation of a couple united in erotic love. Though historical sources relate that Nero later killed Poppaea by kicking her in the stomach while pregnant, this is not something that casts a premonitionary shadow over Monteverdi’s score. It is not even an idea which sits well within this staging, given the constant presence of Cupid (Amy Freston) as a sort of master of ceremonies.

In other respects it was a lively performance, with the comic episodes brought off really sharply. The two Nurses were both sung by men in drag – Poppea’s nurse Arnalta was the larger-than-life tenor Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke, while Ottavia’s nurse, sung by counter-tenor Dominique Visse, was a more subtle creation, all pursed lips and disdaining looks. The interchange between the Page (Lucia Cirillo) and the Damigella (Claire Ormshaw) was brought vividly to life.

Scene from L’Incoronazione di Poppea

Scene from L’Incoronazione di Poppea

Musically, Emmanuelle Haïm and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment never let the lengthy score drag, and the cast was very strong, with Alice Coote’s smoky-voiced Nerone particularly striking. Besides Coote, the other vocal highlight was Tamara Mumford’s warm-voiced, impassioned Ottavia, even if Nerone’s complaint about her ‘barren frigidity’ raised a laugh thanks to Mumford’s advanced stage of pregnancy. The role of Poppea seems to lie well for Danielle de Niese’s soft-grained soprano, and she looks wonderful although she does have a tendency to overact. Only Paolo Battaglia, as Seneca, sounded dry and uneven, though I did find myself wondering, given the forces – a chamber orchestra and smallish voices – quite how successful I would have found the performance if I’d been sitting up in the rear of the Circle or standing in the Gallery.

Ruth Elleson © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Poppea_Glyndebourne_deNiese.png image_description=Danielle de Niese as Poppea product=yes product_title=Prom 18 – L’Incoronazione di PoppeaGlyndebourne Festival Opera at the Royal Albert Hall, 31st July 2008 product_by=Danielle de Niese (Poppea), Alice Coote (Nerone), Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke (Arnalta), et al., Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Emmanuelle Haïm (cond.) product_id=Above: Danielle de Niese as Poppea

All photos by BBC/Chris Christodoulou

Singers from South Africa and Sweden win Seattle Wagner Competition

At the finals Elza van den Heever, a former Adler fellow at the San Francisco Opera, sang "Dich, teure Halle" from Tannhäuser and "Einsam in trüben Tagen" from Lohengrin. Sweden's Michael Weinius, winner of Gösta Winbergh and Birgit Nilsson prizes in his homeland, sang Walther's "Preislied" from Die Meistersinger and "Amfortas! Die Wunde" from Wagner's final opera Parsifal.

Van den Heever, a woman of tall elegance, gained praise in 2007 when she replaced the scheduled Donna Anna in a San Francisco Don Giovanni. She sang her first aria with the requisite exuberance and underscored the poignant melancholy of Elsa's recollections.

Michael Weinius (tenor)

Michael Weinius (tenor)

Weinius brings the richness of the baritone that he once was to his work as a tenor and his choice of the

Parsifal excerpt documented the intellect that goes into his work. Whether, however, his voice is large

enough for American houses remains to be seen. In the 2900-seat McCaw he was at best adequate.

Van den Heever and Weinius each received an award of $15,000 — along with prestige that will greatly further their careers. At the finals Van den Heever was also voted Audience Favorite. The German mezzo, Nadine Weissmann, was chosen its favorite by the members of the Seattle Symphony Orchestra for the program.

Nadine Weissmann (mezzo-soprano)

Nadine Weissmann (mezzo-soprano)

At the finals Weissmann sang "Weiche, Wotan, Weiche" from Das Rheingold and Waltraute's

narrative from Götterdämmerung. Weissman, who has sung several supporting roles in Wagner

performances, is also highly regarded for her incarnation of Carmen. At the competition it was her

command of the tragic undertones of Waltraute's account that was impressive.

Further finalists were American tenor Erin Caves, already a familiar figure in German opera houses, tenor Jason Collins, who has sung numerous supporting roles at Seattle Opera, Australian mezzo Deborah Humble, a member of the Hamburg Opera, British bass-baritone Darren Jeffery and Dresden bass Peter Lobert.

"The judges agreed that we had eight fine finalists," said OS general director Speight Jenkins in announcing the winners on the McCaw stage. " I feel that the level was even higher this year than in the first competition in 2006," said Jenkins." It was a hard-fought decision for the two winners, but a great one."

Israel's Ascher Fisch, SO principal guest conductor, was on the podium for the finals. He opened the program with an appropriately festive account of the Meistersinger Overture.

Jenkins and Fisch selected 30 semi-finalists from the 50 singers who had submitted audition recordings. They chose the eight finalists from this group at auditions in Munich and New York. The singers were between 25 and 39 years old and had not appeared in more than one major Wagner role in a major opera house. These competitiors arrived in Seattle a week before the finals for coaching with SO staff members David McDade and Philip Kelsey and also with Fisch.

Judges for the 2008 competition were Hans-Joachim Frey, general director of Theater Bremen, Wagner superstar Ben Heppner, tenor Peter Kazaras, now artistic director of SO's Young Artists Program, Pamela Rosenberg, former general director of San Francisco Opera and now managing director of the Berlin Philharmonic, Stephen Wadsworth, director of six SO Wagner stagings, and Eva Wagner-Pasquier, great-granddaughter of the composer and Bayreuth artistic consultant.

Founded in 1963, the Seattle has gained a reputation as one of the world's leading Wagner companies. Three production of the entire Ring des Nibelungen have been performed by the SO in 35 cycles since 1975.

The competition was made possible by a grant Seattle's Charles Simonyi Fund for Arts and Sciences. The Simonyi grant also supports other education outreach at Seattle Opera.

Detailed information on the program can be found on the Seattle Opera website, http://www.seattleopera.org.

Adding to the artistic excitement of the competition was the August 14 recital by Ben Heppner that brought a crowd to McCaw Hall. Born and raised in neighboring British Columbia, Heppner sang his first Walther von Stolzing in a Seattle Opera Meistersinger in 1989. He has been closely associated with the company since then and made his role debut as Tristan there in 1998. Unfortunately, at the recital Heppner was suffering from the effects of an laryngitis attack two days earlier and was not in best voice.

In the German section that opened the program — Wagner's "Wesendonck" Lieder, plus songs by Schubert and List, his voice sounded strained and metallic and was capable of only limited dynamic coloring. Far better were the five songs by Henri Duparc that opened the second half of the program. Here Heppner again sang with radiant warmth.

Heppner then turned master entertainer in several English-language songs. He tore off his tie, opened his collar and engaged the audience — to its delight — in easy banter between such favorites as Earnest Charles' "Let My Song Fill Your Heart" and "The House on the Hill," along with Sigmund Romberg's "Serenade" and Oley Speaks' "Sylvia." And although he sang Nicholas Brodzky's "Be My Love" with dedication, his work with the song did not cause elders in the audience to forget the manner in which Mario Lanza had belted out this once-popular song.

In half a dozen encores Heppner included two of Wagner's "greatest hits:" Sigmund's "Winterstürme" from Walküre and Walther's "Preislied" from Meistersinger. Lehar's "Yours is My Heart Alone" was warmly welcomed by the audience.

Ben Heppner and Asher Fisch in Recital

Ben Heppner and Asher Fisch in Recital

Yet one worries about the difficulties that frequent plague Heppner — such as the Tristan cancellations at the Metropolitan Opera last season. At only 52, he should still be free of such problems.

In the recital Heppner's impressive partner at the piano was SO principal conductor Asher Fisch, SO artist of the year in 2006/2007 and for over a decade music director of Tel Aviv's Israel Opera.

The two artists performed on a stage set for Verdi's Aïda, which removed them from the front of the McCaw stage.

Wes Blomster

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Elza_van_den_Heever.png image_description=Elza van den Heever (soprano) [Photo © Rozarii Lynch] product=yes product_title=Seattle Opera’s International Wagner CompetitionAugust 16, 2008, Marion Oliver McCaw Hall product_by=Above: Elza van den Heever (soprano)

All photos © Rozarii Lynch courtesy of Seattle Opera

August 18, 2008

Opera closes ranks against angry diva

Bryce Hallett [Sydney Morning Herald, 19 August 2008]

THE management of Opera Australia is set to dismiss assertions by the opera singer Fiona Janes that the company's musical standards have fallen under its music director, Richard Hickox.

Tenors in Training: The Next Generation

By KATE TAYLOR [NY Sun, 18 August 2008]

Luciano Pavarotti's death last year prompted much speculation about who will eventually replace the triumvirate of Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo, and José Carreras. Most of the discussion has focused on stars in their 30s, such as Juan Diego Flórez and Rolando Villazón. But what about even younger tenors whose careers are developing?

'Ariadne' a joyful jumble

T.L. Ponick [Washington Times, 18 August 2008]

With shabby-chic sets by Erhard Rom, witty direction by Thaddeus Strassberger and sharp conducting by Timothy Long, the Wolf Trap Opera Company's wacky new production of Richard Strauss' "Ariadne auf Naxos" ("Ariadne on Naxos") is an engaging, theatrically over-the-top showcase for the company's incredibly talented young singers.

Grant Park season closes with operatic standards and surprises

BY WYNNE DELACOMA [Chicago Sun-Times, 18 August 2008]

The Grant Park Music Festival closed its 74th season Saturday night with a vibrant helping of opera choruses, a fitting end to a strong Grant Park Orchestra season and a welcome contribution to last week's bountiful schedule of opera performances at Grant Park and the Ravinia Festival.

Cleveland Orchestra's "Rusalka" hailed at Salzburg Festival

Donald Rosenberg [Cleveland.com, 18 August 2008]

The first review of the Cleveland Orchestra's residency at the Salzburg Festival in Austria has arrived. Written by Christoph Lindenbauer of the Austrian Press Agency, it describes the full-scale production of Dvorak's "Rusalka" conducted by music director Franz Welser-Most at the festival's Haus fur Mozart. The production opened Sunday. The English version of the review is headlined, "First all around harmonious festival opera in Salzburg."

Santa Fe Opera hosts U.S. premiere of 'Adriana Mater'

By John von Rhein [Chicago Tribune, 17 August 2008]

SANTA FE—The more things change at the Santa Fe Opera, the more they remain the same.

On a quest to give female composers their due

By Emma Brown [Boston Globe, 17 August 2008]

Laury Gutiérrez has spent the last 16 years rescuing female composers from oblivion.

Berkshire's 'Figaro' opera a treat

By JOSEPH DALTON [timesunion.com, 17 August 2008]

PITTSFIELD, Mass. -- Spying through moist vision a neighboring audience member wiping her own eyes is a pretty good indication that something transcendent and timeless has happened onstage. It's all the more wondrous when the prompting is not a mournful overplayed death scene but two young lovers reconciling as they wrestle about on the ground.

Opera singer's career comes full circle

BY CHRIS SHULL [Wichita Eagle, 17 August 2008]

International opera sensation Joyce DiDonato began her career in Wichita.

The mezzo-soprano studied music at Wichita State University and earned her first stage credits there. She also sang church gigs and performed concerts around town. She graduated from WSU in 1992, and over the next decade worked diligently to become a consummate singing actress.

Puccini at 150, Still Capable of Revelations

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI [NY Times, 15 August 2008]

WHEN Giacomo Puccini died at 65 in 1924, he left behind an estate estimated in today’s currency at roughly $250 million. Has any living classical composer come close to amassing such a fortune?

Lucky star over the Arena

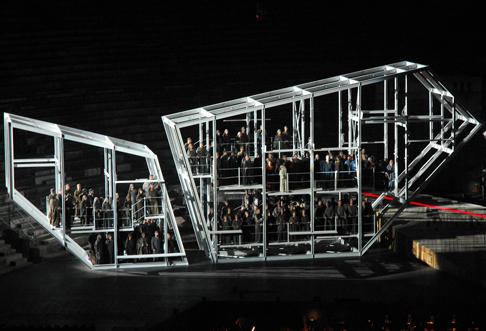

This solemn statement, drawing from Italy’s poet laureate Giacomo Leopardi, is ostensibly the key to Denis Krief’s vision of Nabucco, unveiled last year as the inaugural show for the 85th opera season at L’Arena di Verona and now being revived from late June to late August. By signing all alone direction, scenery, costumes and light design, the French-Italian polymath provided a consistent, almost austere, staging; one relying more on the clash of ideas than on traditional melodramatic gestures. Jerusalem and Babylon, two hostile worlds, are summarized by means of abstract symbols facing each other from opposite sides of the stage. On the left, huge pentagons in white metal resembling a library: Jehovah’s Word incorporated in long rows of books. On the right, gilded cylinder slices boldly pointing towards the sky: the tower of Babylon, obviously. As the conquering Assyrian king storms the Temple on horseback — a real horse, Arena-style, and a pretty skittish one at that — all the books abruptly fall from the shelves and tumble down to the ground with an ominous roar. The Temple is then plunged into the dark, with the Jews singing as if behind the bars of a multi-storied penitentiary. No less destitute in their ankle-length grayish overcoats, Assyrian troopers march to and fro along a steep platform stretching between both monuments. Their queer parade-step, an operette-ish caricature of the German Wehrmacht or the Soviet Red Army, conveys a touch of (unintentional?) humor, though.

After a first controversial reception from the popular outdoor audience, this production is now being paid growing success. Pity that, right on the first sold-out night on July 27, a meeting of stagehands called for a strike in support to a fired colleague and pitch-black clouds were amassing over the beautiful town on the green Adige river. “A stormy night at the Arena — past GM Claudio Orazi once told me — amounts to a thrilling experience. Challenging occasional downpours is part of the excitement, as long as they don’t wholly disrupt the performance. A much seldom occurrence, inasmuch we believe that a lucky star shines over the Arena”. Yet at 9.15 p.m., when Daniel Oren raised his baton for the overture, few among the 14,000-odd patrons filling the stone crater to the brink would bet on a happy end. True, this particular production could not suffer much from the desertion of stagehands. The books were not there, and that was nearly all the damage.

Scene from Act III of Nabucco

Scene from Act III of Nabucco