September 30, 2008

'Manon' gala makes spirits bright

Laura Emerick [Chicago Sun-Times, 30 September 2008]

When Manon, the heroine of Massenet's opera, extols the carefree life of luxury in the work's famous Act 3 gavotte, her joie de vivre virtually lights up the stage.

Classic 'Candide' is a vibrant season opener

By Valerie Scher [Union-Tribune, 29 September 2008]

Listening to Leonard Bernstein's “Candide” at the Birch North Park Theatre was enough to make you marvel at the composer's verve and variety.

Deborah Voigt's Bold Gambit

By FRED KIRSHNIT [NY Sun, 26 September 2008]

American soprano Deborah Voigt has had an up-and-down career over the last decade. Although some of her appearances at the Metropolitan Opera House have been powerful, especially her Sieglinde under both maestros Gergiev and Maazel, she has also disappointed as Elisabeth in "Tannhaeuser" and especially as Floria in "Tosca," where her rendition of Vissi d'arte on opening night was remarkably unmoving. At this point, she needs to prove herself at every appearance.

September 29, 2008

Les Pêcheurs de perles at the Washington National Opera

The 24-year old composer’s sixth and his second to be staged, this opera is a relatively little-known example of 19th-century French opera’s obsession with exotica. Its mostly Oriental stories are populated by savage primitives, and sexy virgin priestesses who in the course of the plot would invariably fall victim to forbidden love. In The Pearl Fishers, Bizet and his librettists were evidently feeling charitable: the guilty passion for once does not prove fatal for the soprano. Instead, she is saved by the villainous baritone, who belatedly discovers his inner hero, and of course gets himself shot for his trouble.

The 25 September performance was generally of good quality. The orchestra did well under the baton of Ciuseppe Grazioli. So did the chorus— when it was on stage and was able to watch the maestro’s baton, that is; the timing in the off-stage numbers was sometimes shaky.

Among the soloists, tenor Charles Castronovo as Nadir definitely stood out from the ensemble. His popular Act 1 romance “Je crois entendre encore” showcased the singer’s strong metallic timbre with excellent projection in all registers. His softly beautiful high notes might perhaps be criticized as too thin; I personally liked the pianos and thought they were stylistically appropriate for a French opéra lyrique, which really should sound different from middle-period Verdi, although it rarely does.

Baritone Trevor Scheunemann as Zurga offered a rich vocal timbre and good blending in the ensembles, of which the famous Act 1 duet “Au fond du temple saint” was a particular highlight of the evening. Scheunemann’s solos were solid, but not particularly memorable. It seemed to me that his concentration on the dramatic aspects of his part— specifically, his character’s inability to decide whether to play a village Count di Luna or Marquis di Poza of Ceylon— sometimes got in the way of sound production.

French soprano Norah Amsellem as Leila was another solid choice in casting. Despite her vocal excellence, however, the singer, like her colleague Mr. Scheunemann, also seemed trapped in the inner contradictions of her character. This time, the issue is not young Bizet’s inexperience as a dramatist, but rather the ideological “baggage” attached to the female lead in French Orientalist opera. Is she a virginal victim or an exotic seductress? One of these two favored clichés demands pure, crystalline high register and “floating” timbre with not much support; the other calls for a throaty, rich low and middle range, with rare but powerful highs. Although Ms Amsellem herself seemed to try charting some sort of middle ground, the casting of this singer, a dramatic soprano, indicates the director’s preference for the seductress image. As a result, in my opinion, this Leila often sounded much too heavy for Bizet’s delicate creation who, after all, is more Michaela than Carmen.

Norah Amsellem as Leila and Denis Sedov as Nourabad

Norah Amsellem as Leila and Denis Sedov as Nourabad

Bass Denis Sedov as high priest Nouraband cut an imposing figure, but despite occasionally powerful sound did not impress with either diction or articulation. In this production, however, the very tall singer’s towering physique was evidently more in demand than his vocal prowess. The stage director, Australian Andrew Sinclair, has attempted to both dramatize and modernize the story by superimposing a political intrigue à la Boris Godunov onto Bizet’s unsuspecting characters, with Mr Sedov’s Nouraband serving as the evil “old order” genius who masterminds the collapse of “liberal” Zurga’s rule. Since no one told the composer about this particular plot twist, there was little in the score to support it. Instead, it was delivered entirely via stage business, which required a lot of “extra-curricular” wandering about the stage from Mr Sedov who did manage to look suitably menacing most of the time.

Another directorial attempt to make Bizet’s dramatically challenging early work more palatable to modern audiences included the revamping of Act 3. It used neither the original love duet nor its common trio substitute, but did entail Leila partially disrobing, then getting assaulted during her duet with Zurga. Alas, the tedious scene was not at all improved by that spectacle. It did, however, allow Ms. Amsellem to showcase once again Leila’s fanciful costume of an orange sari wrapped around a classic “Oriental” ensemble of a skimpy pink top with bare midriff and the see-through harem pants.

The bright palette of reds, oranges, pinks, and turquoise greens dominated the vibrant décor by celebrated British fashion designer Zandra Rhodes. Among the often striking visual effects she created, enhanced by the excellent lighting by Ron Vodicka, particularly notable was the scene of Leila’s first appearance— carried on a live chariot by six men, immobile like a Buddha statue, her orange and gold veil spotlighted against deep purple backdrop. Rhodes’ design ideas were always vivid and always intriguing. What bothered me in her vision was the stylistic discontinuity between the sets and costumes. The latter were colorful, with a nod to geographic authenticity, and in tune with the production’s realist acting and staging. The former— deliberately perspective-less, two-dimensional, with fauvist-leaning color palette and a neo-primitivism-inspired images— were anything but “real.”

The designer’s closest stylistic ally in this production was John Malashock’s choreography, on display so much that it became almost as ubiquitous as Ms Rhodes’ sets. Indeed, even by dance-crazy French standards, ballet was often entirely superfluous, such as the number for what was evidently the “spirits of fire” that provided the background for the introduction to Leila’s Act 1 prayer. When staging The Pearl Fishers, Mr. Sinclair outlawed “proper” ballet as unsuitable for the subject; thus, there was not a pointed shoe in sight (or any kind of shoe, for that matter, as all the dancers performed barefoot). Rare nods to “Oriental” choreography were confined to women’s numbers, which unfortunately suffered from weak execution (this specifically refers to the quartet of Leila’s attendants). The male dances, in a counterpart to Bizet’s imaginary Ceylon, offered a picture of the “imaginary primitives” brandishing fighting pikes: their movements were athletic, aggressive, and purposefully inelegant, with ground stomping, angular hand and feet positions; pirouettes replaced by cartwheels. The Act 3 finale opened with a pas de trois in The Lion King-size animal masks— which was perhaps a little much, but it did save the director a major headache of having to come up with stage business for the endless choruses of this scene.

Norah Amsellem (top, veiled) as Leila, Trevor Scheunemann (foreground) as Zurga

Norah Amsellem (top, veiled) as Leila, Trevor Scheunemann (foreground) as Zurga

Overall, the Washington audiences were presented with a solid, colorful, mostly traditional Les Pêcheurs de perles, well performed (despite some misgivings on my part) by a consistently good cast. The production, which runs through 7 October, offers few vocal fireworks; nor can it boast a truly new word in staging. Yet, for an old-fashioned opera lover, after last season’s symbolist Dutchman and Nazi-fied Tamerlano, these realistic and suitably “Oriental” Pearl Fishers might be a welcome relief.

Olga Haldey

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Pearl_9-08_7.png image_description=Norah Amsellem as Leila and Charles Castronovo as Nadir in Washington National Opera’s The Pearl Fishers (2008). Credit: Karin Cooper. product=yes product_title=Georges Bizet: Les Pêcheurs de perles product_by=Leïla (Norah Amsellem), Nadir (Charles Castronovo), Zurga (Trevor Scheunemann), Nourabad (Denis Sedov). Washington National Opera. Giuseppe Grazioli (conductor). Andrew Sinclair (Director). Zandra Rhodes (Set and Costume Design) product_id=Above: Norah Amsellem as Leila and Charles Castronovo as NadirAll photos by Karin Cooper courtesy of Washington National Opera

September 28, 2008

Cool Cavalli at Covent Garden — La Calisto

No, this is not Berg or Birtwistle, nor some contemporary operatic essay on The Crunch, but the cool, clever and calculating Mr Cavalli and his “La Calisto”, first shown to the discerning and politically savvy public of Venice in 1651. Without a doubt, this production at the Royal Opera (Cavalli’s somewhat overdue debut) is a sizzling success, and shows that Covent Garden could and should embrace the genre of early opera (not to mention “mainstream” baroque) more whole-heartedly in future. If opening night audiences were on the thin side, especially in the more expensive seats, this was no longer true come the second and third performances – word of mouth (and print) has seen to that.

![Véronique Gens as Eternity [Photo © Bill Cooper]](http://www.operatoday.com/Veronique_Gens_Eternity.png) Véronique Gens as Eternity

Véronique Gens as Eternity

One of only two operas that Cavalli wrote with a mythological storyline, it is perhaps the best known today and has been revived several times, most notably by Raymond Leppard back in the 60’s at Glyndebourne. But since then early opera – or rather its interpreters – have galloped on, sometimes like a riderless horse, plunging on and off the track, but always seeking to find a permanent home in the stable of current repertoire. One of its greatest advocates on the stage is David Alden, director of many Handelian successes but new to Covent Garden, and with this “Calisto”, first shown in Munich, he has cemented his reputation for melding old music with modern sensibilities.

First and foremost, Alden is a collaborator. Not for him the roughshod riding of some European directors over text and musical line; rather, he works closely with his musical director (here the redoubtable Ivor Bolton renewing his acquaintance from Munich with the Torrente edition of the original threadbare score) , his long-time scenic associates Paul Steinberg (striking, colourful sets) and Buki Shiff (shimmering cat-walk quality costumes) and his rock-solid cast of experienced period performers led by Sally Matthews in the title role. This Calisto is sexy, cynical, funny and sad – you leave the theatre feeling both uplifted and a little wiser.

Ovid’s recounting of the story of innocent nymph Calisto’s seduction, abandonment, and final metamorphosis from a bear into a heavenly star system is well known, but Cavalli and his librettist Faustini brought in a whole raft of supporting mythic characters – mainly comic - and a secondary plot involving the apparently chaste goddess Diana and her earthly lover Endimione. The music is a roller-coaster of almost-speech, scatter-gun recitative alive with wit, tender ariosi and dramatic, textually replete song, all supported by and entwined with the artistry of the OAE and Monteverdi Continuo Ensemble, led by a visibly-involved Bolton on the podium. This is opera as complete team-work, from early rehearsal through to performance, and it shows.

The vocalists were period-perfect, all real actor-singers. Sally Matthews has an individual, robust yet light-footed soprano that was in wonderful form as Calisto. Her sparkling top was matched with a warm and agile middle voice, occasionally let loose in the second half with real depth of tone and volume to reflect her anguish and incomprehension – a totally human sound in contrast to her god-like tormentors. Chief of these is the eternally-lascivious super-god, Giove (Jove) sung by the very experienced baroque baritone Umberto Chiummo who uses his warm tone and natural agility to great effect. His long-suffering wife, Giunone (Juno) is a smaller part but sung with panache and aplomb by Veronique Gens, whilst the supposedly “chaste” Diana of Monica Bacelli is sung with a scampering delight in both text and music, shading her voice intelligently to reflect her inner conflicts. The only other human character besides Calisto is the rather dopey shepherd Endimione, love-lorn and languishing on various hillsides, and he is sung accurately but rather four-squarely by Lawrence Zazzo who doesn’t quite capture the elegiac elegance of what is Cavalli’s loveliest long-lined music.

![Dominique Visse as Satirino & Guy De Mey as Linfea [Photo © Bill Cooper]](http://www.operatoday.com/Visse_Mey.png) Dominique Visse as Satirino & Guy De Mey as Linfea

Dominique Visse as Satirino & Guy De Mey as Linfea

Unlike the later Handel, Cavalli’s characters have strength in depth right down to the supporting minor roles and it is here that this production really rises above the merely good and becomes excellent – not to mention downright salacious and sexy. Marcus Werba as Giove’s oily side-kick Mercurio, Guy de Mey in hilarious drag as the sex-mad overweight nymph Linfea, Ed Lyon as a stomping Pane, and probably the delight of the evening, the ever-green Dominique Visse hilarious and repulsive as the randy half-goat Satirino, his athleticism and mellifluous braying (do goats bray? they certainly trill) a remarkable tour-de-force that had us in stitches. A whole raft of actor/dancers filled out the scenes, each beautifully and intriguingly costumed as mythological creatures – the eye was filled in a way that was matched by the interwoven magic of the words and music. If you’re tired of grey and empty sets, dark spaces lit by bare bulbs, come and enjoy opera as it should be – Messrs Alden and Bolton and their team will see to that.

Sue Loder © 2008

“La Calisto” at ROH, Covent Garden, continues on 1st, 3rd and 10th October.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sally_Matthews2.png image_description=Sally Matthews as Calisto [Photo © Bill Cooper] product=yes product_title=Francesco Cavalli: La Calisto product_by= Giove (Umberto Chiummo), Mercurio (Markus Werba), Calisto (Sally Matthews), Diana/Destinio/First Fury (Monica Bacelli), Endimione (Lawrence Zazzo), Linfea (Guy de Mey), Satirino/Nature/Second Fury (Dominique Visse), Pane (Ed Lyon), Silvano (Clive Bayley), Giunone/L'Eternità (Vèronique Gens). The Monteverdi Continuo Ensemble and Members of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. Royal Opera House. David Alden (Director). Ivor Bolton (Conductor). product_id=Above: Sally Matthews as CalistoAll photos © Bill Cooper courtesy of Royal Opera House

STRAUSS: Arabella -- Dresden 2005

Music composed by Richard Strauss. Libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

First Performance: 1 July 1933, Sächsisches Staatstheater Opernhaus, Dresden

| Principal Roles: | |

| Count Waldner | Bass |

| Adelaide, his wife | Mezzo Soprano |

| Arabella, their daughter | Soprano |

| Zdenka, Arabella's younger sister | Soprano |

| Mandryka, a Croatian landowner | Baritone |

| Matteo, an officer | Tenor |

| Count Elemer | Tenor |

| Count Dominik | Baritone |

| Count Lamoral | Bass |

| Fiakermilli | Soprano |

| Fortune-Teller | Soprano |

| Three Players | Basses |

| Welko, Mandryka’s bodyguard | Spoken Role |

Synopsis:

The impoverished Count and Countess Waldner seek a rich suitor for their eldest daughter Arabella, and have disguised their younger daughter Zdenka as a boy to save money. Zdenka is in love with Matteo, one of Arabella's admirers, and has written him letters in her sister's name. Arabella believes she will recognise 'the right man', and is curious about a stranger who has watched her outside the hotel. She agrees to choose a husband by the end of the Coachmen's Ball that evening, and leaves for a sleigh-ride. Beset by creditors, the Count has written to a Croatian landowning friend, enclosing a photo of Arabella. The friend's nephew and heir, Mandryka, announces himself. He is bewitched by Arabella's portrait and has come to Vienna to woo her. The Count accepts Mandryka's suit and a loan for the gambling tables. At the ball, Arabella and Mandryka are attracted to each other - he is the stranger she had noticed. He describes a village custom in which a glass of water is offered by a maid to her betrothed to drink. She agrees to marry him, but begs a few hours to bid farewell to her youth. Arabella is proclaimed Queen of the Ball by Milli, the coachmen's darling, and takes leave from each of her former suitors. Zdenka arranges an assignation with Matteo, luring him with a key to Arabella's room. This is overheard by Mandryka, who notes Arabella's departure and falls into a drunken fury, outraging the Countess with accusations of Arabella's infidelity. The Waldners leave the ball and the Count commands Mandryka to follow. Back at the hotel, Matteo believes he has met with Arabella in her darkened bedroom, but in the foyer she is baffled by his allusions. Mandryka has lost his trust in Arabella, and in the growing confusion challenges Matteo to a fight. Zdenka appears in a nightdress and confesses her love for Matteo. Arabella seeks forgiveness from Mandryka and asks her father to bless the union of Zdenka and Matteo. Mandryka, alone, contemplates his feelings for Arabella and sends a glass of water to her room. She brings it down for him to drink, as a symbol of their love.

[Synopsis Source: Boosey & Hawkes]

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Arabella_Denoke_Dresden_Cre.png image_description=Angela Denoke as Arabella (Photo by Matthias Creutziger) audio=yes first_audio_name=Richard Strauss: Arabella first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Arabella3.m3u product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: Arabella product_by=Waldner (Alfred Kuhn), Adelaide (Christa Mayer), Arabella (Angela Denoke), Zdenka (Birgit Fandrey), Mandryka (Hans-Joachim Ketelsen), Matteo (Klaus Florian Vogt), Elemer (Martin Homrich), Dominik (Jürgen Hartfiel), Lamoral (Matthias Henneberg), Fortune-Teller (Andrea Ihle), Semperoper Dresden, Wolfgang Rennert (cond.)Live performance: 24 June 2005, Semperoper, Dresden product_id=For best results, use VLC or Winamp.

September 23, 2008

The new opera buff

By Anthony Tommasini [The Scotsman, 23 September 2008]

IT HAD to happen. Nudity is coming to opera. In recent years, with all the talk from general managers, stage directors and go-for-broke singers about making opera as dramatically visceral an art form as theatre, film and modern dance, traditional boundaries of decorum have been broken. Opera productions have increasingly showcased risk-taking and good-looking singers in bold, sexy and explicit productions.

Fleming Gala Opens the Met’s Season

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI [NY Times, 23 September 2008]

The Metropolitan Opera opened its 125th-anniversary season on Monday evening with a gala Renée Fleming showcase. Everything about the three-part evening was fashioned, quite literally, for Ms. Fleming.

A daring return to simplicity

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 22 September 2008]

Tradition is the new concept. Tired of extreme productions that mystify or alienate audiences, opera companies are returning to a pictorial style that tells the story with minimal fuss. The change is not a whim of fashion.

September 22, 2008

Analyzing music the digital way

By Tom Avril [Philadelphia Inquirer, 22 September 2008]

Ge Wang was every bit the image of an orchestra conductor. Clad all in black, with a dramatic mane of shoulder-length hair parted in the middle, he used fluid gestures to summon forth an auditorium full of sound.

Paer’s Leonora from Bampton Classical Opera

Based, like its more well-known successor, upon Jean Nicolas Bouilly’s play Léonore, ou L’amour conjugal, Paer’s opera has many textual similarities with Beethoven’s drama of heroic rescue and noble sentiments. The faithful wife who disguises herself as a boy in order to reach and rescue her unjustly imprisoned husband forms the core of both works; yet, in Paer’s opera it is not Leonora but the flighty daughter of the jailor who actually releases him from bondage. Indeed, from the light-weight dalliances of the opening moments to the exuberant, self-satisfied moralising of the final sextet (echoes of Don Giovanni or Così?), Paer reveals himself to be more comfortable with the world of petty intrigue and human foibles than with the exalted idealism of Beethoven’s utopian aspirations.

Michael Bracegirdle as Florestano [Photo © Anthony Hall]

Michael Bracegirdle as Florestano [Photo © Anthony Hall]

That said, this imaginative, focused production by Bampton Classical Opera, directed and designed by Jeremy Gray — and first presented under

gloomy summer skies at Bampton Deanery on 18 July — made a strong case,

both musically and dramatically, for this infrequently performed work. Act 2,

in particular, revealed serious musical and dramatic intent, the dramatic

momentum of the recitative and the emotional intensity of Florestan’s long

opening aria of darkness and suffering, proving surprisingly progressive.

Paer makes little distinction between the music of the two female roles, Marcellina and Leonora/Fidele; both are high sopranos, but the star on this occasion was Emily Rowley Jones, who expertly conveyed the spirited passion, tempered by an essential kindness and innocence, of the jailor’s daughter. Rowley Jones possessed the stamina required of this demanding role, and her voice remained well-centred and sweet throughout; virtuosic flourishes were dispatched with apparent ease, and intelligently nuanced to serve the dramatic situation. She brought Mozartian grace and wit to the opening scenes; her movements on the small stage were well-choreographed and deftly executed. It was through the dynamic contrast between Marcellina’s unrequited passion for ‘Fidele’ and her impatient dismissal of Giacchino’s courtship that the drama gained vitality.

Both female roles demand a wide range and much staying power — Marcellina requires the compass of a Queen of the Night; in the title role, Cara McHardy initially seemed ill-at-ease, her breath control a little insecure and the more virtuosic passages not always firmly controlled. However, as the performance progresses she showed herself on occasion more than capable of rising to the challenges of the taxing coloratura and bringing both meaning and beauty to her interpretation. Unfortunately her lack of confidence dramatically was noticeable in the ensembles where she appeared uncomfortable and at times vocally subdued.

Michael Bracegirdle as Florestano, Cara McHardy as Leonora [Photo © Anthony Hall]

Michael Bracegirdle as Florestano, Cara McHardy as Leonora [Photo © Anthony Hall]

As in previous Bampton productions, Adrian Powter, as Rocco, revealed his instinct for the dramatic moment, moving confidently and establishing a strong stage presence. He injected appropriate weight and bluff into his boasting tirades, which benefited also from excellent diction. Samuel Evans, as the hapless prison janitor, Giacchino, similarly demonstrated sound comic timing and nuance, and together they significantly contributed to the dramatic momentum, which might have been hampered by the many long reflective arias and by the extensive duet for Marcellina and Leonora in Act 2.

The challenges of the twenty-minute aria for Florestan which opens Act 2 are many; but Michael Bracegirdle proved himself able to shape the various sections of his painful, desolate lament on his lengthy suffering in the darkness into a convincing whole, employing an extensive dynamic range and sensitive tonal variations.

Jonathan Stoughton as Pizzarro [Photo © Anthony Hall]

Jonathan Stoughton as Pizzarro [Photo © Anthony Hall]

Despite the foreboding guillotine and imposing dungeon walls which

dominated the set, it was difficult for the cast to inject any real menace

into Paer’s drama. There is no prisoner’s chorus to emphasise the themes

of imprisonment and despair; and Pizarro, the prison governor, is a rather

unconvincing stage-villain — his comic arrogance emphasised here by his

Napoleonic cape and eye-patch. His bluster may be less than threatening, but

Jonathan Stoughton sang securely if a little blandly. It was not

Stoughton’s fault that, following a rather feeble confrontation with

Leonora, Pizarro found himself cast in chains, and one immediately forgot

about him. Indeed, there is a deflation of dramatic tension towards the close

of Act 2: the arrival of Marcellina, demanding a marriage proposal from

‘Fedele’ somewhat dispels the threat of violence, and the arrival of Don

Fernando, sung here with warm radiance by John Upperton, swiftly and

effortlessly restores harmony and accord.

However, Paer’s opera does have many notable features, not least its strong melodic character. This is evident from the first bars of the overture, a seemingly simple medley of forthcoming themes, which has an original feature in the heroine’s romantic ‘motto’ theme, heard three times here and subsequently reiterated most effectively at crucial points in the action. Throughout the orchestration surprises and delights: while the rather clichéd trumpet call introducing the sinister dungeon setting and the three percussive chimes announcing the hour of Florestan’s murder may fail to send a shiver up the spine, overall the writing revealed some striking colours, exploiting unusual instrumental combinations, especially for the woodwind. The score was well-executed by the London Mozart Players. Situated behind the imposing set, conductor Robin Newton led them in lively fashion; indeed, he set off at a pace which left the singers somewhat trailing in the orchestra’s wake, anxiously glancing at the distantly-placed monitors; but secure ensemble was quickly restored and the overall balance between soloists and orchestra was well-judged.

Paer’s Leonora is an excellent example of its genre — a semi-seria opera, in which the frivolous and tragic co-exist and interact. It may be that the comic plot slightly overshadows the high drama of wrongful imprisonment and tyranny, but this intelligent, well-paced production by Bampton Classical Opera made a convincing case for the composer’s melodic lyricism and left this listener eager for another opportunity to hear this unfairly neglected work.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Paer_Leonora1.png image_description=Emily Rowley Jones (Marcellina) and Samuel Evans (Giacchino) [Photo © Jeremy Gray] product=yes product_title=Ferdinando Paer: Leonora product_by=Rocco (Adrian Powter), Marcellina (Emily Rowley Jones), Giacchinno (Samuel Evans), Leonora (Cara McHardy), Don Pizzarro (Jonathan Stoughton), Don Florestan (Michael Bracegirdle), Don Fernando (John Upperton). The London Mozart Players. Conductor: Robin Newton. Director: Jeremy GrayPerformance of 16 September 2008, St John’s Smith Square, London product_id=Above: Emily Rowley Jones (Marcellina) and Samuel Evans (Giacchino) [Photo © Jeremy Gray]

Puccini's Il Trittico at Los Angeles Opera

The Bartok featured a spare set with ghostly lighting effects and puppets, and ended with Samuel Ramey's Bluebeard garroting Denyce Graves's Judith onstage with her flowing red scarf. Later, in his manic Schicchi, the bird puppets from the Bartok made a reappearance, linking the two productions.

In contemplating a full staging of Puccini's brilliant (if unwieldy in terms of length and staging requirements) Il Trittico, LAO decided to dispense with Friedkin's earlier Gianni Schicchi but to ask the director to create productions of the first two parts of the triptych, Il Tabarro and Suor Angelica. For the comedy, Placido Domingo realized a long-held desire to employ Woody Allen. This show opened the 2008-09 season, and as seen on Sunday, September 21st, it proved to be a successful venture, although with a striking difference in directorial approach between the two Friedkin sections and that of Allen.

Santo Loquasto's designed traditional sets for the first two operas, impressively scaled and detailed. Friedkin had a cramped front stage area for Il Tabarro, once Michele's barge has drawn up to the wharf. Without the option of theatrical effects, Friedkin proved to be a rather routine stage director, with nothing very imaginative in his handling of the actors. Licitra's Luigi stuck his thumbs in his belt like a member of the Lollipop Guild, and Mark Delavan's Michele looked ready to kill someone from the moment he barged off his barge. Anja Kampe, however, portrayed a truly touching Giorgetta, vital if not obviously young, and sensual without deserving the harsh judgement of her husband when he suspects her of adultery. Matthew O'Neill slightly overplayed the comedy of his drunken Tinca, if enjoyably so, but both John Del Carlo (actually luxury casting for such a small role) and Tichina Vaughn as the husband and wife Talpa and Frugola made an interesting dramatic contrast to the sordid triangle at the heart of the drama.

Besides taking the acting honors, Kampe also sang with a feminine power that suggests she should look into some other great Puccini roles. Licitra is finally gaining control of his spinto instrument, although when it came time for his final big moment on the folly of jealousy, his voice didn't ring out with quite the volume he had mustered earlier in the evening. Delavan had all the gruffness needed for the darkness in Michele, but the sad and lonely side that might evoke some pity hasn't developed yet. Friedkin did find a way to suggestively link his two operas, as he had done before: this time, when the songseller appears, two nuns join the crowd.

Il Tabarro: Anja Kampe, Salvatore Licitra [Photo by Robert Millard]

Il Tabarro: Anja Kampe, Salvatore Licitra [Photo by Robert Millard]

Loquasto's convent for Suor Angelica had one somewhat original touch, a grated entrance for the appearance of the Principessa, which also provided a dramatic exit after her character has delivered her devastating news to Angelica and gotten the desired signature on a legal document. Larissa Diadkova not only had all the imperiously dark tones for the role, but also a forbiddingly dark visage from the rear, as she walked away from her prostrate niece. Otherwise this was Sondra Radvanovsky's show, and she triumphed. Her huge voice didn't float the highest notes, but her threading down of the volume had the desired effect. Radvanovsky's Angelica appeared sad from the start, so her suicidal impulse made sense, but the singer also did well by the tricky moment when Angelica realizes she has committed a mortal sin and begs Mother Mary to save her. Here, Friedkin went full out, with a Mary figure in flowing robes descending from the rafters, as the son of Angelica appears from the chapel. Freidkin even had another sister appear to witness the miracle. That went over the top for your reviewer, but the amount of sniffling and sobbing in the audience provided evidence that it worked for many.

After two settings presented much as they might have looked at the opera's debut, Loquasto, for Woody Allen, went for an updating of Gianni Schicchi. We were somewhere in mid-20th century, in a huge room with a metal-works circular stair leading to a loft with no ostensible purpose. There was almost no bare space for an actor to sit, with knickknacks and housewares strewn everywhere, not to mention the spaghetti noodles still in the pot where the will would be discovered (and that spaghetti, dangling from the will, became a classic running joke that went on past its effective date). Allen has directed for the stage before, and his films tend to be more talk than action as well, so it may not be a surprise that he proved more adept than Friedkin at moving the singers around and getting individual performances from each of them. Jill Grove filled out (amply!) a truly malevolent, and ultimately murderous, Zita. Andrea Silvestri's muscular bass pushed other voices to the side as his former-mayor character strutted around the stage. Best of all, Allen found a way to make the two lovers interesting. Saimir Pirgu not only sang with the sort of hormonally-charged tenor voice needed for Rinuccio, but managed to be quite funny as well. Even better, instead of being an airheaded "daddy's girl," Jennifer Black (subbing for Laura Tatulescu) slunk on stage as a very physical Lauretta, with hips to kill, and if they don't work, a stiletto in her garter. But Allen didn't have to end the opera with the two youngsters getting down to business, or "up" to it, at the top of the circular staircase.

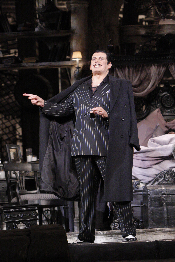

Gianni Schicchi: Thomas Allen [Photo by Robert Millard]

Gianni Schicchi: Thomas Allen [Photo by Robert Millard]

At the heart of all this farcical nonsense was Sir Thomas Allen, dropping trou with the best of them as a Sicilian underworld figure, in a dark pinstripe suit, black "wife-beater" t-shirt under his silk dress shirt, all topped by an imposingly shined and buffed head of black hair. Sir Thomas didn't hold back, and as should be, once he strutted onto the scene, all eyes were on him. But if only he could have talked his director out of the misbegotten concept just before curtain, when the enraged Zita reappears and sends Schicchi to Hades with a knife thrust. Here special credit must go to the young actor who portrayed Gherardo and Nella's son, Sage Ryan. This blonde tyke got thrown around the stage a lot, and when he cried over the dying figure of Schicchi, we shared his regret more than enjoyed any intended comic twist.

Since he came on board 2 seasons ago, James Conlon has made himself beloved here in Los Angeles, and the dynamic energy and sensitive shadings he provided these three great Puccini scores are typical of his fine work with the now first-rate LAO orchestra.

Il Trittico makes for a show of Wagnerian length (almost four hours on Sunday), but with as many merits as this production offered, it should figure in the repertory more prominently than it does. LAO now goes onto Madama Butterfly, for the third time in about 5 seasons. Your reviewer hopes this Il Trittico makes a comeback before Cio-Cio-san does.

Chris Mullins

| Il Tabarro | |

| Michele | Mark Delavan |

| Giorgetta | Anja Kampe |

| Luigi | Salvatore Licitra |

| Talpa | John Del Carlo |

| Frugola | Tichina Vaughn |

| Tinca | Matthew O’Neill |

| Song Vendor | Robert MacNeil |

| Suor Angelica | |

| Sister Angelica | Sondra Radvanovsky |

| The Princess | Larissa Diadkova |

| Sister Genovieffa | Jennifer Black |

| The Monitress | Tichina Vaughn |

| The Mistress of the Novices | Catherine Keen |

| The Abbess | Ronnita Miller |

| Gianni Schicchi | |

| Gianni Schicchi | Thomas Allen |

| Rinuccio | Saimir Pirgu |

| Lauretta | Jennifer Black |

| Zita | Jill Grove |

| Gherardo | Greg Fedderly |

| Nella | Rebekah Camm |

| Simone | Andrea Silvestrelli |

| La Ciesca | Lauren McNeese |

| Betto Di Signa | Steven Condy |

| Marco | Brian Leerhuber |

Music for the Court of Maximilian II

All three composers were variously attached to the Habsburg court in the middle of the sixteenth century and the music of all three amply reveals both the richness of the mid-century style and the careful craftsmanship they brought to it. Cinquecento’s program is devoted to a mass and several motets from the Habsburg orbit by these three with an additional motet by Lasso. The program coheres not only through contextual proximity, but more significantly by the way the pieces reflect music’s function within a web of patronage. Some of the motets (Maessen’s “Discessu” and Lasso’s “Pacis amans”) explicitly name Maximilian, and these form a direct salute to the House of Habsburg. The text of Vaet’s motet, “Ascendetis post filium,” is dedicated in praise of Maximilian; he is not named in the text specifically, although the theme is one of monarchical succession, possibly written for his assuming the throne of Bohemia or Hungary. This salute to Maximilian is furthered in Galli’s imitation mass based on Vaet’s motet, and significantly, the salute to the patron also becomes a salute to Vaet, as well--a two-fold doffing of the compositional hat!

The performances are sublime. Cinquecento offers a sumptuous sound, exquisitely focused and yet rich in tone, as the opening motet, Vaet’s “Videns Dominus,” reveals from its very first notes. The contrapuntal style of the pieces is generally dense, although the ensemble’s lines are unflaggingly lithe, taming the density with clarity. And the suppleness of line is matched with a fluid sense of melisma, as in the flowing passage work of the “Benedictus” in Galli’s mass. Other moments are characterized by the ensemble’s finely crafted control, as in the “Et incarnatus” from the mass, or the beautiful stillness of some of the final chords.

The bass of Cinquecento, Ulfried Staber, sings with an especially gratifying sound, a delight in itself, of course, but also a sound that seems foundational for the ensemble tone as a whole. It is as though his sound is “pulled up” through the other registers, yet remains in place as both model and fundament.

The Music of Maximilian II is a splendid recording of music that is refreshingly little-known, sung with consummate skill and artistry.

Steven Plank

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Max_II.png

image_description=Music for the Court of Maximilian II

product=yes

product_title=Music for the Court of Maximilian II

product_by=Cinquecento

product_id=Hyperion CDA67579 [CD]

price=$21.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Catalog?catalog_num=67579&x=0&y=0

September 21, 2008

STRAUSS: Arabella — Salzburg 1958

Music composed by Richard Strauss. Libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

First Performance: 1 July 1933, Sächsisches Staatstheater Opernhaus, Dresden

| Principal Roles: | |

| Count Waldner | Bass |

| Adelaide, his wife | Mezzo Soprano |

| Arabella, their daughter | Soprano |

| Zdenka, Arabella’s younger sister | Soprano |

| Mandryka, a Croatian landowner | Baritone |

| Matteo, an officer | Tenor |

| Count Elemer | Tenor |

| Count Dominik | Baritone |

| Count Lamoral | Bass |

| Fiakermilli | Soprano |

| Fortune-Teller | Soprano |

| Three Players | Basses |

| Welko, Mandryka’s bodyguard | Spoken Role |

Synopsis:

The impoverished Count and Countess Waldner seek a rich suitor for their eldest daughter Arabella, and have disguised their younger daughter Zdenka as a boy to save money. Zdenka is in love with Matteo, one of Arabella’s admirers, and has written him letters in her sister’s name. Arabella believes she will recognise ‘the right man’, and is curious about a stranger who has watched her outside the hotel. She agrees to choose a husband by the end of the Coachmen’s Ball that evening, and leaves for a sleigh-ride. Beset by creditors, the Count has written to a Croatian landowning friend, enclosing a photo of Arabella. The friend’s nephew and heir, Mandryka, announces himself. He is bewitched by Arabella’s portrait and has come to Vienna to woo her. The Count accepts Mandryka’s suit and a loan for the gambling tables. At the ball, Arabella and Mandryka are attracted to each other – he is the stranger she had noticed. He describes a village custom in which a glass of water is offered by a maid to her betrothed to drink. She agrees to marry him, but begs a few hours to bid farewell to her youth. Arabella is proclaimed Queen of the Ball by Milli, the coachmen’s darling, and takes leave from each of her former suitors. Zdenka arranges an assignation with Matteo, luring him with a key to Arabella’s room. This is overheard by Mandryka, who notes Arabella’s departure and falls into a drunken fury, outraging the Countess with accusations of Arabella’s infidelity. The Waldners leave the ball and the Count commands Mandryka to follow. Back at the hotel, Matteo believes he has met with Arabella in her darkened bedroom, but in the foyer she is baffled by his allusions. Mandryka has lost his trust in Arabella, and in the growing confusion challenges Matteo to a fight. Zdenka appears in a nightdress and confesses her love for Matteo. Arabella seeks forgiveness from Mandryka and asks her father to bless the union of Zdenka and Matteo. Mandryka, alone, contemplates his feelings for Arabella and sends a glass of water to her room. She brings it down for him to drink, as a symbol of their love.

[Synopsis Source: Boosey & Hawkes]

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DellaCasa_Rothenberger.png image_description=Lisa Della Casa and Anneliese Rothenberger audio=yes first_audio_name=Richard Strauss: Arabella first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Arabella1.m3u product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: Arabella product_by=Otto Edelmann (Count Waldner), Ira Malaniuk (Adelaide), Lisa Della Casa (Arabella), Anneliese Rothenberger (Zdenka), Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (Mandryka), Kurt Ruesche (Matteo), Helmut Meichert (Count Elemer), Georg Stern (Count Dominik), Karl Weber (Count Lamoral), Eta Köhrer (Fiakermilli), Kerstin Meyer (Fortune-Teller), Willi Lenninger (Welko). Chor der Wiener Staatsoper, Wiener Philharmoniker, Joseph Keilberth (cond.)Live performance, 29 July 1958, Festspielhaus, Salzburg product_id=For best results, use VLC or Winamp.

September 19, 2008

Pergolesi’s Home Service Really Delivers!

The United States premiere of Pergolesi’s Home Service will be presented by The Chamber Opera of Memphis in cooperation with the University of Memphis Rudi E. Scheidt School of Music on Thursday, October 16 at 7:30 p.m. in Harris Concert Hall (3775 Central Ave.).

Pergolesi’s Home Service Really Delivers!

Admission is free.

What happens to a tiny little opera company in times like these, when the arts are no longer so generously funded? In Bent Lorentzen’s opera Pergolesi’s Home Service, Impresario Umberto Pergolesi has created a mobile opera company that will perform pint sized productions in your own home: Norma in your roof garden, Tosca in your dining room, La Traviata in your bedroom or even Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman in your bathroom. Pergolesi’s Home Service is a sophisticated new version of the Baroque Opera La Serva Padrona.

Composer Bent Lorentzen, one of the outstanding figures in contemporary Danish music, will attend the premiere. Lorentzen’s music resists categorization into conventional slots. He has flirted with various styles, but their impact has not deprived his music of its personality and individuality of expression. He often collaborates with Michael Leinert who co-wrote the libretto for Pergolesi. School of Music faculty member Susan Owen-Leinert wrote the English translation of the work.

German stage director Michael Leinert will direct the production. Susan Owen-Leinert is cast as Theater Director Umberto Pergolesi. April Hamilton, a graduate student at the School of Music, performs as Serpina, an opera singer. Moira Logan, Associate Dean and Director of Research and Graduate Studies for the College of Communication and Fine Arts, takes the versatile role of Vespone, an actress and mime. School of Music professor John Mueller plays the virtuosic trombone part. Mark Ensley, Director of Opera Studies at the School of Music and Music Director of The Chamber Opera of Memphis conducts from the keyboard.

The Chamber Opera of Memphis, founded by Susan-Owen Leinert and Michael Leinert, was created to establish a forum for contemporary and experimental music theater. Their 2007-2008 production of Peter Maxwell Davies’ The Medium was performed at the School of Music, at the Hamburger Kammeroper and the Robert Schumann Hochschule Duesseldorf in Germany, where they received great reviews and public response.

Located in one of the nation’s most influential musical cities, The Rudi E. Scheidt School of Music at the University of Memphis is a different kind of music school. Here, students and faculty are committed to the essence of performance that is so unique to the region. This essence, regardless of genre, is the creativity, originality, quality and entrepreneurial spirit that are central to the rich musical heritage of Memphis.

Accredited by the National Association of Schools of Music, the School offers 20 degrees in more than 24 areas of concentration, taught by 45 world-class faculty members who are recognized from Carnegie Hall to The Grammys®. With more than 250 faculty, student and guest performances each year, we are where the music is.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Pergolesi_Home_Service.png image_description=Pergolesi’s Home Service Really Delivers! product=yes product_title=Pergolesi’s Home Service Really Delivers! product_by=The Chamber Opera of Memphis in cooperation with the University of Memphis Rudi E. Scheidt School of MusicOresteia at Miller Theatre

Now they are all grand old (mostly dead) men, and the public, which is as curious about new sounds in concert music as in popular music, having heard such sounds in the background of a hundred films, is no longer afraid of what they do not immediately understand. They are no longer being told that they should like it, or should ignore this or that from the past; they are freer to select and explore. We live in an atmosphere where the new no longer means just one sort of new (it never did, but it had that reputation); we have come to expect the unexpected, and appreciate it when it shows up.

Nowhere is this change in audience expectations and interest more startling than among the opera audience. This is good news for opera companies and for composers, though it may not be great news for traditional singers (few modern composers have their specific training or methods of expressivity in mind) and for the audience who loves the old-fashioned vocal style.

These reflections came to me after a spring whose chief Met Opera delight was Satyagraha, whose chief summer festival interest was Zimmermann’s Die Soldaten, and an autumn opera season commencing with Xenakis’s Oresteia. None of these are traditional operas performed in a traditional manner. None of them could easily fit into a typical opera house repertory season. And the audience, immensely various in age and style and attitude, has been tremendously enthusiastic for all three. Vocally they represent differing poles: Satyagraha provided some of the loveliest traditional opera singing of the year, showing that living composers can do this if they wish to, though some may carp that this particular drama was hardly of a traditional variety. (You could say the same about Parsifal, and Cosima Wagner did, come to think of it.)

Xenakis – like his fellows other than Henze – would have been reluctant to try to compose an opera of the traditional type, for performance by any traditional company. His setting of Aeschylus’s trilogy began life as incidental music for a performance of the three plays. Over the years, he set other sections of the play, responding to certain characters and situations within it. Only his death in 2001, at the age of 79, stopped his tinkering – who knows? Another twenty years and he might have completed an opera score. Most of the work as we have it is percussive background to scenes of the drama, or else settings of the choruses – there is only one solo singer, who declaims several roles.

To the ancient Greeks, of course, the chorus were always a principal character – indeed, the original one, chanting religious ritual and story, to which soloists enacting it were subsequently added. Many Greek plays take their titles from the chorus, who it represents (Suppliants, Bacchantes, Phoenicians, Knights, Wasps), and the puzzle over how they are to present the chorus, how their message is to be displayed to modern audiences more interested in the individual conflicts, is a stumbling block for modern revivals of the plays. It is less of a stumbling block when the plays are sung, as we are accustomed to choral singing, even drama in choral song, in ways we have ceased to accept choral chant.

In the performance of Oresteia that opened the thirty-fifth season of the Miller Theater at Columbia (an awkward place to stage any sort of theater, as the building was devised as a lecture hall, and sight lines for the stage – and, nowadays, surtitles – are not good), the chorus sat around the central stage with the orchestra high above them on three sides of it as well, and the central space was occupied by six dancers and one singer. In concert, as composed, this Oresteia might have been numbing to watch, but the acting out of the various legends under discussion by the six agile dancers held attention – as did the highly theatrical performance of the chief player of percussion on a tower stage right.

The actors, presumably, were giving us representations of the tales of Iphigenia’s sacrifice, Agamemnon’s homecoming and murder by his wife, Orestes’s vengeful homecoming and murder of his mother, and the Athenian compromise that allowed Orestes to escape the Furies aroused by his matricide – an Athenian mythic explanation of the replacement of primitive feud law (each murder causing another) with the rule of impersonal justice, and the sleep of blood lust sanctified by ritual remembrance and euphemism. Euphemism empowers what is too fearful to name, and in calling the Furies “the Kindly Ones” and libating to them on the family hearth, the Athenians paid tribute to the terror that remains below the surface, theoretically concealed and forgotten by the new dispensation.

When Ariane Mnouchkine staged the trilogy in Brooklyn a dozen years ago, she was asked why the chorus of feral dogs, representing unsatisfied blood lust, remained after the three Furies had departed, leading to an unforgettable final image as they leaped for the throat of their enemy, the defiant goddess of civilization, Athene herself, Mnouchkine replied, “Because they are always there.” Indeed, under the surface, the yearning for bloody personal vengeance does continue to lurk, unsatisfied by the artificial decrees of justice and the state. And in some places not far from Aeschylus’s Athens today, blood feud (after brief suppression in Communist times) has returned, and innocent sons of killers are forced to spend their lives in hiding rather than risk what their society still sees as necessary murder.

So Aeschylus’s tales are still relevant, and probably will remain so while the species endures. It is good to see them effectively staged, even if the staging was a bit of a puzzle. (There are operatic settings of portions – or all – of the trilogy; I have never seen Pizzetti’s Clytemnestra or all of Taneyev’s Oresteia.) At the Miller, I could never quite figure out which dancer was portraying which character, though I think the short, wiry, balding guy who did manic pirouettes was Orestes – perhaps if I’d been able to read the titles while the chorus chanted, this would have been clearer. In any case, their gyrations kept one rapt while incomprehensible sounds filled the air.

The singer was bass Wilbur Pauley, whom I have heard over the years in works of Handel, Kurt Weill, Meredith Monk and John Corigliano – Oresteia does not call on him for Handelian orotundity; more often he was obliged to leap between deep Agamemnon sounds to falsetto for Cassandra’s prophecies, and when he sang the lines of the goddess, he alternated both extreme registers. This was the third of three performances, and his falsetto was in trouble by the end of it, but his urgency and passion were always in evidence.

I did wonder if the men’s choruses (not the women’s shocking ululations, which burst in later, I think at Clytemnestra’s death) resembled the sound of the chants of the Greek Orthodox Church (which Xenakis would have known quite well), and in turn if that fabric derived from the ritual chant common to pre-Christian religions all around the Eastern Mediterranean, and then in turn if these bore any relation at all to the sounds Aeschylus heard at the premier of his trilogy. There is no way to know; my classicist and Orthodox friends do not think so – when the Christian liturgy was put together in Byzantine times, there was a conscious desire to break any link with the pagan past, and by that time the Greek tragedies were no longer performed; they had become a literary tradition. By the time the Renaissance intellectuals of Mantua attempted to reconstruct ancient tragedy, accidentally inventing opera in the process, they were over a thousand years removed from any memory of the sounds of tragedy, and two thousand years from the Oresteia. Like them, Xenakis invented his own style of play, and also like them, we can devise our own ways to make it theatrical for our sort of audience.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Oresteia25.png image_description=Scene from Oresteia by Iannis Xenakis (Photo by Richard Termine) product=yes product_title=Iannis Xenakis: Oresteia product_by=Wilbur Pauley, bass; David Schotzko, solo percussion; Oresteia Chorus, Young People’s Chorus of New York City, International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE). Directed by Luca Veggetti. Performance of September 17. product_id=Above: Scene from Oresteia by Iannis XenakisAll photos by Richard Termine courtesy of Miller Theatre

Souvenir of a Golden Era: The Sisters Garcia

Now Decca re-releases Marilyn Horne’s “Souvenir of a Golden Era,” which does Bartoli one better by also honoring Malibran’s younger sister, Pauline Viardot.

No direct comparisons can be made between Bartoli’s “Maria” and the first disc of Horne’s “Souvenir,” as the discs covers different selections. Bartoli tends to focus on more obscure repertory (with the exception of “Casta Diva”), especially pieces that play to her strengths in speed and agility. Horne chose selections that primarily highlight Malibran’s key roles in Rossini, from Rosina’s “Una voce poco fa,” to Tancredi’s “Di tanti palpiti.” She also sings as Bellini’s Romeo, and most surprisingly, delivers the “Abscheulicher!” of Beethoven’s Leonore.

Horne sings impeccably on each of three tracks, her lows weighty, the highs with a soprano’s confidence and security. Your reviewer found her Rosina curiously flat, as Horne earned a reputation as a woman of great humor and vivacity in roles that required those attributes (and offstage as well). Perhaps the uninspired direction of Henry Lewis (with the Suisse Romande orchestra) deserves the blame. However, even in the ostensibly dramatic scenarios of Tancredi and Semiramide, Horne’s seamless production can give a sensation of disassociation from the text. As pure vocalizing the singing can’t be criticized, and yet these pieces should scintillate more than they do. Again, Lewis might be the culprit here.

The second disc, dedicated to Pauline Viardot’s roles, covers a wider range of repertory, resulting in a more entertaining listening experience. The disc starts with more Rossini, then moves to French opera - Gluck, Gounod, Meyerbeer — before a wild swing back to Italy and Verdi’s Azucena. In the lusher French pieces, Horne’s gorgeous tone pays big dividends, although she can’t save “J’ai perdu mon Eurydice” from the risible effect produced by Lewis’s frantic, “pop”-like pacing. As for that final track from Il Trovatore, with the mad gypsy woman’s two big arias jammed together, surely there are scarier Azucenas. In the context of this recital, however, Horne’s version has such musicality that the familiar music rings out with a welcome freshness.

With more inspired musical leadership, “Souvenirs of a Golden Era” would be an indisputably great recording. And for listeners who only care about voice, that qualification need not apply. For others, the best of the selections here, especially on the second disc, earn the recording a strong recommendation.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Souvenir_Golden_Era.png

image_description=Souvenir of a Golden Era: The Sisters Garcia

product=yes

product_title=Souvenir of a Golden Era: The Sisters Garcia

product_by=Marilyn Horne, L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, Henry Lewis

product_id=Decca 475 8493 [2CDs]

price=$22.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=186927

September 18, 2008

Dr. Ulrike Hessler First Woman Appointed Intendant to Semper Oper in Dresden

For the first time in its 169 year history, the Saxonian State Opera — home to world premiere performances of most Richard Strauss and several Wagner operas — has appointed a woman as its General Director.

Dr. Ulrike Hessler First Woman Appointed Intendant to Semper Oper in Dresden

Today Saxony's Secretary of Science & Arts, Dr. Eva-Maria Stange, announced the decision that Mrs. Hessler will lead the house starting 2010, succeeding current intendant Gerd Uecker.

Ulrike Hessler (52) has been working at the Bavarian State Opera since 1984, working her way up from assistant to the press spokesperson's to director for public relations and program development. When the Bavarian State Opera was without a GM during the 2006/07 and 2007/08 seasons, she formed an interim directorship with Music Director Kent Nagano, running the day to day affairs of the opera house.

Before working in the world of opera, Mrs. Hessler, who wrote her Ph.D. thesis about Bernard von Brentano’s literature of exile, worked as a free lance journalists for Bavarian Radio and a has written for Harper’s and Vogue. She is a frequent guest lecturer at Universities abroad and has been an Overseas Member of the Board of Governors der Tel Aviv University since 1990.

According to the Saxonian Ministry of Science & Arts, the factor deciding in favor of Ulrike Hessler was “the way how Mrs. Hessler thinks about the future of an opera house like this and how a very active repertoire- and ensemble theater with such a long tradition will successfully the tough international competition.” Another important factor was the vision with which Mrs. Hessler has developed ideas for sharpening the company's profile and the importance she places on better communications of the house both internally and externally. Not the least her extensive leadership experience at the Bavarian State Opera and her range of contacts to singers, directors, dancers, and musicians has played a role. The former Director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, English National Opera, and Bavarian State Opera, Sir Peter Jonas, was among the advisers to the ministry in this decision. The famous tenor and conductor Peter Schreier welcomed the decision, describing his impressions of Mrs. Hessler as an “incredibly creative and decisive” collaborator.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Hessler.png image_description=Ulrike Hessler product=yes product_title=Dr. Ulrike Hessler First Woman Appointed Intendant to Semper Oper in Dresden product_by=Above: Ulrike Hessler (Photo courtesy of Creative Consultants for the Arts)September 17, 2008

Lawrence Brownlee Expands Repertoire in 2008-09 Season

He is lauded continually for the beauty of his voice, his seemingly effortless technical agility, and his dynamic and engaging dramatic skills. His schedule regularly comprises a varied array of debuts and return engagements at renowned music centers for appearances with the world’s pre-eminent opera companies, orchestras and presenting organizations.

Mr. Brownlee’s 2008-09 season finds him firmly ensconced in the bel canto music for which he is so admired, adding a trio of new characters to his repertoire: two by Rossini and one by Donizetti. His first engagements are performing what has become his calling-card role, Il Conte Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia, in three of Germany’s leading houses. At Dresden’s Sächsische Staatsoper (August 28, 30 & September 8) he courts and slyly plans his elopement with the lovely Rosina (Carmen Oprisanu), joined on stage by Fabio Maria Capitanucci (as the enterprising Figaro), Michael Eder (as the overprotective and slightly lecherous Don Bartolo), and Kurt Rydl and Georg Zeppenfeld (sharing the honors as the oily Don Basilio); the production is by Grischa Asagaroff and Riccardo Frizza conducts. For the Deutsche Staatsoper Berlin (Unter den Linden) he appears in the Company’s classic Ruth Berghaus production (September 16, 20, 26 & 30), donning various disguises in an attempt to fool his love’s guardian, in the company of Katharina Kammerloher, Alfredo Daza, Bruno de Simone and Alexander Vinogradov, with Julien Salemkour leading from the pit. For Mr. Brownlee’s first time at the Festspiele Baden-Baden (October 3 & 5) he treads the boards in the same Bartlett Sher Barbiere production in which he made his spectacular 2007 Metropolitan Opera debut. Here his colleagues are: Anna Bonitatibus, Franco Vassallo, Maurizio Muraro & Reinhard Dorn, all conducted by Thomas Hengelbrock. He participates in the Richard Tucker Music Foundation’s Annual Lincoln Center Gala (October 26) where he joins a starry roster that, as of this writing, includes: Maria Guleghina, Hei-Kyung Hong, Marcello Giordani, Željko Lučić and Paulo Szot, with Patrick Summers at the helm. (Mr. Brownlee’s has twice been recognized by the RTMF: in 2003, when he was the winner of a Career Grant, and in 2006, at which time he was the Foundation’s Award winner.) With the Opera Company of Philadelphia he appears as Lindoro in a Stefano Vizioli production of L’italiana in Algeri, conducted by one of his mentors, Company Music Director Corrado Rovaris (November 14, 16m, 19, 21, & 23m). Mr. Brownlee’s Lindoro ultimately escapes confinement and is reunited with his lady-love, the enterprising Isabella (Ruxandra Donose); Daniel Belcher (Taddeo) and Kevin Glavin (Mustafà) play Mr. Brownlee’s foiled rivals for the Italian lady’s affections. (His first OCP engagement was in November 2006 in Cenerentola.)

The tenor starts off the new year with a guest stint on a gala tribute to Plácido Domingo offered by the New Orleans Opera (January 17). Following that are three recitals, all accompanied by his long-time collaborator, pianist Martin Katz. January 24 marks his first time on the Spivey Hall Series at Clayton State University, outside of Atlanta, Georgia. Next is a joint-recital with soprano Sarah Coburn at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater (January 31) as part of the Vocal Arts Society’s series. (Washington has played an important part in the tenor’s career, having witnessed his artistry in: four recitals, including one as the recipient of the Marian Anderson Award; Carmina Burana with the National Symphony; as well as in three projects with Washington Concert Opera, La donna del lago, Tancredi & I Puritani). The final recital is for the University Musical Society in Ann Arbor, Michigan (February 7), site of his 2006 Tancredi with the Detroit Symphony. In Europe, Mr. Brownlee does another trio of Barbieres: for his return to the Wiener Staatsoper (February 12 & 15) in the venerable and much-loved Günther Rennert production with Michaela Selinger, Carlos Alvarez, Wolfgang Bankl & Janusz Monarcha, conducted by Marc Piollet. (His introduction to the Viennese public was in this same role in 2006); for a reprise run at the Unter den Linden (February 17 & 20), in which he joins forces with Katharina Kammerloher, Alfredo Daza, Renato Girolami & TBA, all led by Asher Fisch; and finally in a Gilbert Deflo production at the Staatsoper Hamburg (February 28) with Maria-Christina Damian, George Petean, Renato Girolami & Wilhelm Schwinghammer, with Alexander Winterson marshalling the musical forces. (The tenor’s Hamburg debut was in La fille du régiment in 2006, which he subsequently repeated in 2007). A new role follows, as Giannetto in La gazza ladra, for Bologna’s Teatro Comunale, March 22 – 31. (His initial time with the Company was in 2004 as Comte Ory). He performs this Rossini rarity with: Mariola Cantarero/Paula Almerales, Silvia Trò Santafe/José Maria Lo Monaco; Simone Alberghini/Luca Tittoto, and Alex Esposito/TBA; the director is Damiano Michieletto teaming up with conductor Michele Mariotti. Mr. Brownlee returns to the Metropolitan Opera, this time as a Prince, Don Ramiro in La Cenerentola (May 1, 6 & 9), reuniting him with his Met-debut conductor, Maurizio Benini, and Elīna Garanča as the rags-to-riches Angelina, his Rosina on their Sony recording of Barbiere. The remainder of the ensemble includes: Simone Alberghini (Dandini), Alessandro Corbelli (Don Magnifico) and John Relyea (Alidoro) in a production by Cesare Lievi. The last of these performances is part of the Met’s series of high definition transmissions to movie theaters around the world. Previously heard and seen in Trieste’s Teatro Verdi in Cenerentola, the tenor now brings his L’italiana Lindoro there, led by Bruno Campanella (May 29, 31; June 3, 9 [10]). He repeats a run of Barbieres in Hamburg (June 7, 20, 23 & 25) with a slightly different cast (Silvia Tro Santafé, Oleg Romashyn, Renato Girolami & Tigran Martirossian), before concluding his season in the U.S. with triple debuts: his introductory booking at the Caramoor Festival in New York, where he presents himself in two new roles: Nemorino in L’elisir d’amore (July 18) and Idreno in Semiramide, (August 1), both helmed by bel canto specialist Will Crutchfield. The remainder of the cast of L’elisir is still to be announced; Semiramide also features Angela Meade (as the guilt-stricken eponymous Queen of Babylonia), Vivica Genaux (as the warrior-prince Arsace) and Daniel Mobbs (as the murderous Assur).

The 2008-09 season sees the release of two of Mr. Brownlee’s most recently completed CDs, both on labels new for the tenor and centered around the works of Rossini: on Naxos, L’italiana in Algeri conducted by Alberto Zedda, taken from the live 2008 performances at the Rossini in Wildbad Festival; and, on Opera Rara, an exploration of the composer’s song output, for which he is joined by colleagues Mireille Delunsch, Jennifer Larmore, Catharine Wyn-Rogers, Mark Wilde and Brindley Sherratt, with Malcolm Martineau at the piano. The summer of 2008 saw the DVD release by Decca of a performance from the Covent Garden world premiere run of Lorin Maazel’s 1984, in which the tenor created the role of Syme.

For further information, please access Mr. Brownlee’s website at: www.lawrencebrownlee.com

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Brownlee.png image_description=Lawrence Brownlee (Photo by Dario Acosta) product=yes product_title=Lawrence Brownlee Expands Repertoire in 2008-09 Season product_by=Above: Lawrence Brownlee (Photo by Dario Acosta)John Adams: a composer as clever as he's courageous

Ivan Hewitt [Daily Telegraph, 17 September 2008]

A musician's memoir would probably not be your first choice for light reading, but make an exception for Hallelujah Junction, the memoirs of American composer John Adams, who last year turned 60.

September 16, 2008

A September Day Like No Other for a Downtown Family

By STEVE SMITH [NY Times, 16 September 2008]

Depicting the unimaginable on a theater stage is a daunting prospect. In the original production of the opera “Doctor Atomic,” the director Peter Sellars and the composer John Adams represented the detonation of the first nuclear bomb with an ominous countdown, a flash of light and a profound silence. For some viewers this solution was a striking evocation of an event literally too overwhelming for the human mind to process. Others found it a disappointing cop-out.

Prom 61 — Verdi's Requiem

This year it was the turn of the BBC Symphony Orchestra under their Chief Conductor Jiři Bělohlávek, along with the BBC Symphony Chorus, Crouch End Festival Chorus and a first-class line-up of vocal soloists.

What was truly remarkable, and frankly it should be something that can be taken for granted in high-profile professional performances, was the consistency in intonation and tone quality among the four soloists. They were big voices but there was not a wobble among them. The octaves between soprano and mezzo in the Agnus Dei were sung with such mutual sensitivity that the effect was almost one of a single voice (though ironically, the couple of bars where the two female voices are actually in unison revealed that they do not naturally blend). Joseph Calleja’s beauty and strength of tone made the Ingemisco searching and not in the least self-indulgent, while the pinpoint accuracy of Ildebrando d’Arcangelo gave the broken phrases of the Mors stupebit an authoritative finality which made the rests work at least as effectively as the notes.

Though Violeta Urmana's Libera me never quite sounded as though she was terrified for her mortal soul, the sheer power and accuracy of her delivery made for a hair-raising experience. Pace my reservations about this one-time mezzo’s ability to crown the orchestral sound with her top notes, even the quiet ones. Olga Borodina cancelled at short notice and was replaced by Michelle DeYoung, whose glinting mezzo in the Liber scriptus left the audience in little doubt that this WOULD be the fate in store for them.

For the Sanctus and Libera me fugues, Bělohlávek’s tempi were somewhat steady, perhaps due to the need to accommodate the substantial massed choral forces. As in many past performances of this piece, the trumpets of the Tuba mirum were arranged at various points throughout the Hall, with the third group being high up in the Gallery at the back; spatially it’s very effective, but musically it’s a mistake because of the sheer distance and resultant time-lag. They were never going to be in time with each other.

Generally, though, the orchestral sound was full and impressive, and the combined effort made for the finest and most powerful performance of the Verdi Requiem I can recall.

Ruth Elleson © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Verdi_standing.png image_description=Giuseppe Verdi product=yes product_title=Prom 61 — G. Verdi: Requiem product_by=Violeta Urmana (soprano), Michelle DeYoung (mezzo-soprano), Joseph Calleja (tenor), Ildebrando d'Arcangelo (bass). BBC Symphony Chorus, Crouch End Festival Chorus, BBC Symphony Orchestra. Jiří Bělohlávek (cond.)Royal Albert Hall, 31 August 2008

Prom 51 — St. John Passion

The centrepiece of the homage was a performance of the St John Passion, the shorter, tauter and more uplifting of Bach’s two extant Passion settings.

Sir John Eliot Gardiner was at the helm of this one, delivering a performance that was both exactingly schooled and dramatically compelling. Admittedly his firm-set ideas on historically-informed performance are a trifle predictable, and can be irritating after a while: the over-stressing of the first beat in every bar of the opening chorus was somewhat bothersome, as was the exaggerated running-through of the ends of phrases of the chorales wherever the text contains no comma.

The soloists were led by the experienced Evangelist of Mark Padmore, who always manages to convey a stark emotional connection with the music while still retaining a refined delivery. Other than Padmore, the singers were variable; Peter Harvey’s Christus was more than adequate, but the most interesting and dramatically compelling was the bass-baritone Matthew Brook as Pontius Pilate, whose role in John’s gospel is so much more prominent than in Matthew’s more detailed account.

Soprano Katharine Fuge sang with limpid tone, but her phrasing was short-breathed, and her voice is such a small sound that I wonder if she was audible at all in the further reaches of the Hall. I take issue with whoever came up with the idea for the ‘sobbing’ ornamentation in the B section of ‘Zerfließe, mein Herze’; it was the one really tasteless moment of the concert. Alto Robin Blaze was very uneven in his first aria, which is perhaps a little high-lying for him, but much more satisfying in his second, ‘Es ist vollbracht’ which comes at the moment of Christ’s death. Nicholas Mulroy and Jeremy Budd shared the tenor arias, Mulroy acquitting himself with more consistency.

The Monteverdi Choir, in which the soloists also participated, performed with vocal colouring and facial expression appropriate to each of the dramatic choruses. The choir were radiantly uplifting in the closing chorus and chorale, affirming Man’s confidence in the presence of a hitherto non-existent gateway to Paradise.

Ruth Elleson © 2008

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bach_Haussmann.png image_description=J. S. Bach by Elias Gottlob Haussmann (1748) product=yes product_title=Prom 51 — J.S. Bach: St. John Passion product_by=Mark Padmore (Evangelist), Peter Harvey (Christus), Katharine Fuge (soprano), Robin Blaze (counter-tenor), Nicholas Mulroy (tenor), Jeremy Budd (tenor), Matthew Brook (bass). Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Sir John Eliot Gardiner (cond.)Royal Albert Hall, 24 August 2008

September 15, 2008

Let's Go, Verdi! A Change-Up At Nats Park

By Teresa Wiltz [Washington Post, 15 September 2008]

Opera beamed into a ballpark has a distinctly different vibe than a concert-hall experience: It's T-shirts vs. tuxedos, baseball caps vs. opera glasses, chicken tenders vs. champagne, D.C. heat and humidity vs. central air.

'Bonesetter's Daughter'

Joshua Kosman [SF Chronicle, 15 September 2008]

"The Bonesetter's Daughter," which had its world premiere Saturday night at the San Francisco Opera, explodes onto the stage in a burst of circus extravagance: acrobats flying through the air, the nasal squawk of Chinese reed instruments from the balcony, elaborate visuals centered around elemental images of fire and water.

An Opera of an Epic, Composed in Stages

By ALLAN KOZINN [NY Times, 15 September 2008]

In his 11 years at the Miller Theater, George R. Steel has made creative programming an art form in itself and has constantly raised the bar. When he planned this season, his goal was to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the renovation of Columbia University’s old McMillan Theater and its reopening as the Miller Theater. As it turns out, it is also Mr. Steel’s valedictory season, though most of it will be in absentia.

Philip Glass: Confessions of a chameleon

By Fiona Sturges [The Independent, 14 September 2008]

As a child, the composer Philip Glass worked at his father's radio- repair shop in Baltimore, which doubled as a small record store. It was there that he was exposed to a huge variety of music, from Schubert and Bartok to Hank Williams and Elvis. "I liked nearly all of it," he said years later. "People forgot to tell me some stuff was better than others."

Expanding audiences and ambitions

By John von Rhein [ Chicago Tribune, 14 September 2008]

In its first five seasons of operation, the Harris Theater for Music and Dance has proved an enormous boon to its resident classical music groups, as well as others that use the acoustically admirable, state-of-the-art facility.

Why the critics swatted The Fly opera

Richard Ouzounian [Toronto Star, 13 September 2008]

There was an old lady who swallowed a fly.

Actually, It was a whole chorus of middle-aged male reviewers who did the dirty deed, but when they had finished with David Cronenberg and Howard Shore's opera of The Fly, which opened in Los Angeles last Sunday night, they had not only swallowed it, but regurgitated it onto the pages of the continent's papers as well.

Proms conclude with Last Night

[BBC, 13 September 2008]

The BBC Proms season has ended with the traditional Last Night concert in London's Royal Albert Hall.

Thousands of people also attended open-air events on big screens in Hyde Park, Belfast, Glasgow and Swansea.

Turandot, Hampstead Theatre, London

By Ian Shuttleworth [Financial Times, 11 September 2008]

Charm, wonder, beauty ... not words often associated with Bertolt Brecht. More often dour, didactic, dull. The Young Vic’s revival earlier this year of The Good Soul Of Szechuan impressed some but left many doubting whether there was continuing dramatic life to such works after the dismissal of communism as a global ideology.

September 14, 2008

The Second to Last Night of the Proms – Beethoven’s 9th Symphony

Wear a silly hat, wave a flag and maybe the cameras will spot you. Then Mom will see you on TV 10,000 miles away. The Second-to-Last Night though, is the “real” Last Night for music lovers and it’s traditionally observed with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Justly so, for there is no music more symbolic of the Proms ethos than this wonderful symphony. “Alle Menschen werden Brüder !” All men shall be brothers. No wonder it’s the theme song of the European Community. In these troubled times, Schiller’s message is even more relevant. Since this Prom is broadcast worldwide and available online, it will reach wherever technology permits – a universal experience that crosses boundaries, bringing people together for a moment of communal celebration.