November 30, 2010

Garsington Opera’s Glorious New Setting Unveiled With The Magic Flute

Press Release [30 November 2010]

Having taken up its new home on the Getty family’s magnificent Wormsley Estate in Buckinghamshire, Garsington Opera now announces its first season at Wormsley

(2 June - 5 July 2011). Three operas will be presented, beginning with Mozart’s much loved work, The Magic Flute, following with Rossini’s inspired comic opera, Il Turco in Italia and finally the British premiere of Vivaldi’s rarely performed work La verità in cimento.

November 29, 2010

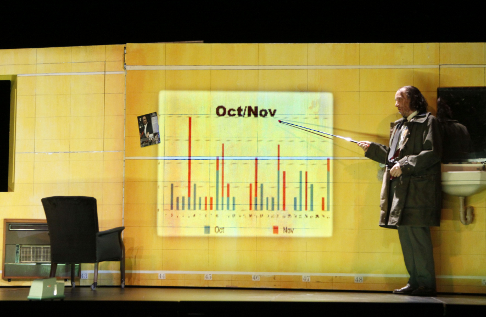

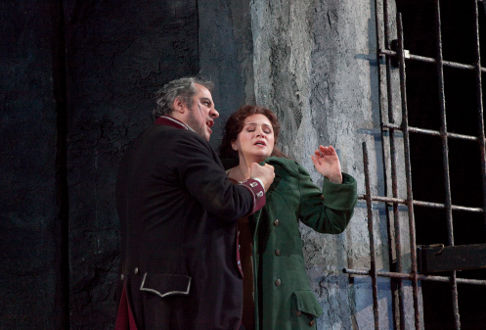

Rigoletto, Opera Australia

The revival is even more welcome thanks to the outstanding performances of Michael Lewis and Rigoletto and Emma Matthews as Gilda.

The swinging, cynical sixties Moshinsky creates is the perfect world for the Duke. Paparazzi swarm around his act one party where showgirls dance with bishops.

Act one springs along in this updated guise, the circus-like party music even sounding like the sort of music Fellini’s regular composer Nino Rota would have written had he lived a century earlier.

Michael Yeargan’s revolving ‘doll house’ set shows the Duke’s palace, the street where Rigoletto meets Sparafucile, Rigoletto’s house and Sparafucile’s inn. A quick quarter turn in acts two and four and you have some open space for Gilda’s abduction and the final father-daughter duet. It all works splendidly and is another of Opera Australia’s landmark productions. The set also concentrates the action close to the front of the stage so, when the many set pieces come along, the characters are conveniently up stage nicely placed to deliver their arias.

Michael Lewis is a model Verdi baritone, perfect diction, smooth legato and clear, ringing top. Lewis exploits every note of the music, sung and unsung, to convey character. Seen during the prelude, applying a grotesque clown make-up (anticipating Heath Ledger’s Joker from Batman), Lewis’s Rigoletto then stands to show this Rigoletto’s extra handicap. Crippled, Lewis beetles about on walking sticks. Lewis’s thirty years singing the role bring insights into the character’s words and music illuminate every dimension of Rigoletto’s tragedy big and small from his terrified freeze at Monterone’s curse to the perfectly timed pause and wild yowl when Gilda dies.

Emma Matthews is radiant as Gilda. Mentored in the role by Joan Sutherland, she now takes the highest alternatives at the close of “Caro nomo”, singing with a security and sophistication that would make her late, great predecessor proud. Matthews’s acting matches her singing and she creates an understandably fatalistic young woman out of Gilda. Her murder scene is actually shocking; she strides fearlessly into the tavern so Maddalena seems to see it is a woman, not a man, and shrieks with horror as Gilds is stabbed. Jacqueline Dark, in the unlikely double act of Gilda’s untrustworthy guardian and then co-assassin brings a Freudian undertone perfectly in keeping with the story.

Rosario la Spina makes less of the Duke than his colleagues seeming to sing without much involvement but this has the advantage of suggesting the Duke’s detachment from his many victims.

Michael Lewis as Rigoletto [Photo by Jeff Busby courtesy of Opera Australia]

Michael Lewis as Rigoletto [Photo by Jeff Busby courtesy of Opera Australia]

Conductor Marko Letonja and Orchestra Victoria do some splendid work with shaping the tender moments. The Rigoletto/Gilda duets are as lovingly shaped as they are sung and the often-repeated ‘curse’ theme and storm music are thrilling without being bombastic.

Michael Magnusson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/OA_Rigoletto.gif image_description=Scene from Rigoletto [Photo courtesy of Opera Australia] product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Rigoletto product_by=Rigoletto: Michael Lewis; Gilda: Emma Matthews (Natalie Jones 25 & 27 November); Duke of Mantua: Rosario La Spina; Sparafucile: Richard Anderson; Maddalena/Giovanna: Jacqueline Dark; Monterone: Jud Arthur; Marullo: Luke Gabbedy; Borsa: David Corcoran; Count Ceprano: Richard Alexander; Countess Ceprano: Jane Parkin; Usher: Clifford Plumpton; Page — Jodie McGuren. Director: Elijah Moshinsky (Revival Director: Cathy Dadd); Conductor: Marko Letonja; Set & Costume Designer: Michael Yeargan. State Theatre, The Arts Centre (November 22, 25, 27 December 1, 3, 7, 10, 18, 2010) product_id=Above: Scene from Rigoletto [Photo courtesy of Opera Australia]Le nozze di Figaro, Opera Australia

Armfield’s view of late eighteenth century life in Spain is a dark one. The Almaviva household is held in the same disdain as the then monarch Carlos IV and his dysfunctional family. Goya inspires Dale Ferguson’s costumes; Countess Almaviva in particular, in oyster satin (and thanks to Rachelle Durkin’s supermodel physique and bearing) has the devastating allure of Goya’s beloved Duchess of Alba. Goya even makes an appearance in act three to ‘photograph’ Figaro’s nuptials and, just as he did in his portrait of the Royal Family, captures a household in sexual, social and political turmoil.

Fergusson’s sets feature deliberate anachronisms that, to my eyes, show the contemptible attitude of the Almaviva’s to their staff. A shabby, vinyl reclining armchair dominates act one for Cherubino then the Count to hide behind or in. It’s the sort of out-of-date furniture that would normally be dumped but here is given to the servants to furnish their quarters. For the wedding celebrations the Count provides a battered tea urn and cafeteria crockery!

I prefer a deeper voiced Figaro contrasting the lighter voiced Count as here. With that gruff edge to his voice Teddy Tahu Rhodes exemplifies the peasant against the more refined voice of Peter Coleman-Wright’s aristocrat. In “Se vuol ballare” he embellishes the repeated theme. The result is a little ungainly but in terms of characterisation the growl works splendidly. Even better in “Non più andrai” he directs the second verse to the Count, seated smugly in the recliner chair, and, towering over the trembling Count, warns him his days of philandering are over too and reminding us how revolutionary this opera (and the play it derives from) was feared to be. Armfield fills the opera with insights like these and the principal singers — especially Coleman-Wright, Rhodes, Durkin and Tiffany Speight — integrate them into their performances with easy assurance.

Tall and sleek Durkin’s arms glide naturally into gestures both graceful and, at appropriate times, erotic. When, in act two, the Count tries to force her away from the door to force open the closet where Cherubino hides, he at first violently lays his gloved hands on her only to let them roam over her breasts and body making the sexual connection still existing between the two — despite their current marital problems — alarmingly obvious. Durkin’s response to this rare moment of contact with her faithless husband, melting at his touch, is simultaneously elegant and erotic. Erotic obsession is the basis of this opera after all and this insight into that eroticism created a frisson. The Countess’s attraction to Cherubino was insightfully played up too; the Countess wilting to his act two serenade like Gomez used to when Morticia spoke French.

Speight’s voice grows in size and stature with each appearance. Speight also has charming way with and special claim on Mozartian maids. Sian Pendry bravely displays the rampaging teenage sexuality of Cherubino behaving at times like a spaniel in heat! She neatly negotiates the rapid pace set for “Non so piu” beautifully enunciating the words as do he rest of the cast.

The secondary characters weave through the story with only occasional success. Elizabeth Campbell’s Marcellina is another character caught in a precarious situation. Her frustrations run deeper than mere anxiety over her age. Her favour with Count Almaviva, depends on her winning her case against Figaro. In Campbell’s hands there is that sense Marcellina is greatly relieved when she finds Figaro is her son and she can escape to bourgeoisie security as Bartolo’s wife. When Armfield’s production was first staged Don Basilio’s and Marcellina’s arias were cut. They were restored for the revival in Sydney, although Marcellina’s is excised for this Melbourne season. The tenor Robert Tear specialises in singing Basilio and devotes an entire essay to him in his book Singer Beware offering an illuminating analysis into “the quality of thought which might invest a small part with a fresh interest and, at the same time, probably alter the usual balance of the opera. “If the aria, is cut,” he writes, “the character becomes extremely hard to play simply because the chance of explaining his character to the audience is taken away, all the earlier behaviour seeming merely eccentric or stupid.” Basilio is a man of great intelligence, according to Tear, “more intelligent than anyone else in the Almaviva household” the seemingly bizarre aria “In quelli anni cui dal poco” is making a point about this “musician/thinker’s position in a philistine aristocratic house of the period.” While the near-revolutionary sentiments of Figaro’s are extrovertly apparent in Armfield’s clever twist in “Non più andrai”, there could have been similar possibilities with Basilio’s aria explaining his philosophy and how it helped him survive the “fooleries of class and politics” surrounding him. Conductor Marko Letonja actually highlights the ascending horn passages at the end of Balisio’s aria so they ring out with a confidence worthy of Beethoven and suggest maybe the triumphant Basilio is another plebeian hero. Kanen Breen plays Basilio primarily for laughs and by the time the aria arrives the character has become a rococo incarnation of Kenneth Williams. It’s an assured performance however; the character slithers around with decreasing fear of his betters.

There is a touch of early music practice from the orchestra; fortepiano replacing the usual harpsichord and the strings adopting that occasionally ‘wiry’ sound associated with early music practice. Acts one and two work the best in this current revival, the sexual and social strain made delightfully relevant by director and cast.

Michael Magnusson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/OA_Nozze_2010.gif image_description=Rachelle Durkin as Countess Almaviva and Peter Coleman-Wright as Count Almaviva [Photo by Branco Gacia courtesy of Opera Australia] product=yes product_title=W. A. Mozart: Le nozze di Figaro product_by=Count Almaviva: Peter Coleman-Wright; Countess Almaviva: Rachelle Durkin; Susanna: Tiffany Speight; Figaro: Teddy Tahu Rhodes; Cherubino: Sian Pendry; Marcellina: Elizabeth Campbell; Bartolo: Warwick Fyfe; Basilio/Curzio: Kanen Breen; Barbarina: Claire Lyon; Antonio: Clifford Plumpton; Bridesmaids: Katherine Wiles & Margaret Plummer; Director: Neil Armfield; Conductor: Marko Letonja Anthony Legge (November 23 & 27); Scenery & Costume Design: Dale Ferguson. State Theatre, The Arts Centre. November 17, 20, 23, 27, December 2, 9, 11 & 15, 2010. product_id=Above: Rachelle Durkin as Countess Almaviva and Peter Coleman-Wright as Count Almaviva [Photo by Branco Gacia courtesy of Opera Australia]Get with the contemporary classical programme? We already have

By Tom Service [Guardian, 29 November 2010]

There's already a healthy debate going on in response to Alex Ross's article. Some of the comments agree with him that music has a particular problem, or suggest that John Cage et al really are the equivalent of the emperor's new clothes; others - rightly, in my view - exhort the naysayers to "open your mind, experience the new, and you may find that you enjoy music a good deal more".

November 28, 2010

Is China poised to become next opera superpower?

By Bill Schiller [Toronto Star, 28 November 2010]

BEIJING—When Italian opera star Leo Nucci set off in 2009 on his first-ever working visit to China, he concedes he felt a measure of excitement.

Messiah at Community of Christ Auditorium, Kansas City

By Timothy McDonald [Kansas City Star, 28 November 2010]

The holiday season is replete with traditions, and the annual performance of Handel’s monumental oratorio Messiah is one of the region’s richest musical customs.

What would Mozart say? Storm over new Don Giovanni opera showing gang rape by men wearing Jesus Christ T-shirts

By Daily Mail Reporter [28 November 2010]

A new version of Don Giovanni which includes a gang rape by a group of masked men wearing Jesus Christ t-shirts was today causing a storm in the West End.

LA Opera’s Rigoletto

By Mark Swed [LA Times, 28 November 2010]

Around midway through Verdi’s “Rigoletto,” an odious cuckolded count asks the hunchbacked court jester in Mantua, "What’s the news," as Los Angeles Opera translated the Italian on supertitles Saturday night at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. "That you’re more annoying than ever," Rigoletto answers.

November 26, 2010

'Aida' by San Francisco Opera review: No subtlety

By Joshua Kosman [SF Chronicle, 26 November 2010]

Verdi's "Aida" returned to the War Memorial Opera House on Tuesday night to conclude the San Francisco Opera's fall season with a bang - a loud and often ungainly one, I'm afraid.

Hugh the Drover, Cadogan Hall, London

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 26 November 2010]

When Ralph Vaughan Williams set out, early in his career, to turn a boxing match into opera, he could hardly have chosen a more impractical challenge. In the event, he did rather well: the fight between Hugh and his rival in love brings the first half of Hugh the Drover to a rousing climax.

November 25, 2010

Die Entführung aus dem Serail, OAE, Queen Elizabeth Hall

By Alexandra Coghlan [The Arts Desk, 25 November 2010]

A problem child in any number of ways, Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail doesn’t always get the professional attention it deserves, certainly not from London companies. The opera’s last outing at the Royal Opera House dates back almost a decade, and you’d have to look even further back to find it in English National Opera’s performing catalogue.

November 23, 2010

A Dog’s Heart, ENO

‘The current climate’ is a dreary, defeatist phrase, generally an excuse for enemies of all that it is to be human to diminish our humanity further; nevertheless, it seems to inform so much of what we do and even hope for at the moment, that to have a new opera by an un-starry Russian composer, of whom most of the audience most likely will never have heard, performed at the Coliseum is worth a cheer or two in itself. (The current practice of many companies and orchestras in parochially commissioning works only from British artists is unworthy of organisations that would claim a place upon the world stage.) A couple more cheers — again, at least — must be granted the show’s resounding theatrical success. For more than anything else this is a triumph for Simon McBurney and Complicite. After a number of false starts in its current mission to import values from the non-operatic theatre, however one wishes to term it, ENO, in collaboration with the co-producing Holland Festival, really hits the target this time.

A fuller synopsis can be found elsewhere, but briefly, A Dog’s Heart reworks Mikhail Bulgakov’s satire. Cesare Mazzonis’s libretto is here translated by Martin Pickard. The opera opens with a stray dog — the superb puppet work inspired by Alberto Giacometti (click here for the sculpture in question) — mistreated by men, apparently rescued and promised a dog’s paradise by a distinguished scientist, Professor Filipp Filippovich Preobrazhensky. The parallelism between the new workers’ state and the animal’s condition is revealingly maintained and deepened throughout, likewise the repellent superior pretensions of Preobrazhensky — the name will be familiar to students of Bolshevism and Stalinism — both as scientist and as human. Eventually, the professor sees his chance for true scientific glory. Having fed up the dog, whom he has named Sharik, he transplants human testicles and a pituitary gland, to create a ‘new man’, Sharikov. Sharikov’s antics leave him, the professor notes, at the most rudimentary evolutionary level, yet that is hardly Sharikov’s fault; indeed he garners hope from association with proletarian organisations, further horrifying his creator. The professor disowns him and conducts a second operation. The creature is once again a ‘mere’ dog. I could not help wondering about a potential English play on words: is the dog man another representation of our desire to create a god man?

Peter Hoare as Sharikov

Peter Hoare as Sharikov

What marks A Dog’s Heart out from many collaborations is that

it was collaborative from the beginning, a joint project involving composer,

librettist, and Complicite. This tells; I suspected it must have been so before

I discovered that it was. A true sense of theatre is present from the very

outset, the opera opening without warning. Pacing is keen throughout and the

stage direction puts most to shame. The puppetry, previously mentioned, is

wonderful — this includes a cat, whom Sharikov cannot help but chase

— but so are mechanics such as scene changing, so often something hapless

to endure in the opera house. Sets from Michael Levine and his assistant, Luis

Carvalho, are exemplary: never fussy, but evocative both of period and of their

stage in the drama. The grandeur of the professor’s rooms — envied

by the proletarian house committee, but our scientist has friends in high

places — provides an apt link with an older Moscow, whilst Finn

Ross’s NEP-style projections make clear what has changed. The silhouetted

— in part — operation was very well handled, bringing subsequent

gore into greater relief.

This is, to my knowledge, the only opera whose first act closes with the injunction, ‘Suck my cock!’ Why, in the supertitles, coyly write ‘c*unt’ thus, when everyone could hear the word, and why suppose, especially in such a context, that the sensibilities of Daily Mail readers should be considered? The ‘profane language’ is not, in that bizarre circumlocution, ‘gratuitous’, but integral to the plot, above all to the dog-man’s characterisation. Where it can somewhat irritate in Ligeti’s Le grand macabre — though there is, of course, Dadaist (un-)reason for it there too — it would be several suburbanisms too far for anyone to object in the present case.

Music, it must be said, takes second billing, though that is not a unique phenomenon: Gérard Mortier’s parting shot at the Opéra national de Paris, Am Anfang, billed Anselm Kiefer’s installation before Jörg Widmann’s score, and Widmann is a more famed composer than Alexander Raskatov. And yet, though I flatter myself that I can be called a musician, I did not mind, which must say something about the sum of the parts. It was far from easy to discern where one ‘contribution’ began and another stopped. For instance, doubling of parts seemed to have a point beyond economy. This is not Lulu; there was none of Berg’s carefully-crafted parallelism and symmetry. But the taking on of different roles said something about anonymity, appearance from and disappearance into the proletarian crowd, and Warhol-like moments in the limelight.

Steven Page as Professor Filipp Filippovich Preobrazhensky and Graeme Danby as Fyodor/Newspaper Seller/Big Boss

Steven Page as Professor Filipp Filippovich Preobrazhensky and Graeme Danby as Fyodor/Newspaper Seller/Big Boss

I cannot imagine wishing to hear to Raskatov’s score outside the theatre — and whilst I should definitely be tempted by a subsequent dramatic project, I should find it difficult to evince enthusiasm for hearing his music in the concert hall. Nevertheless, it works in the theatre. (People say that of Verdi, but that apparent success has always eluded me.) It is recognisably ‘Russian’- sounding, closer perhaps to Schnittke than anyone else, though there may be other influences of whose work I am simply unaware. Often somewhat cartoonish, it occupies its (relatively) subordinate role cheerfully and has its individualistic moments, for instance in the use of bass guitar. Connections to earlier Russian composers are manifest too. This is not Prokofiev (certainly not Prokofiev at his operatic best, for instance The Gambler or The Fiery Angel), but it is a good deal more entertaining than most Shostakovich — or Schnittke, for that matter. I cannot say that I could hear much, or any, influence from late Stravinsky or Webern, such as David Nice suggested in his otherwise helpful programme note. (Incidentally — actually, not incidentally, but importantly — the programme features, McBurney’s contributions included, were of an unusually high standard.) Thinning of textures on certain occasions aside, it was difficult to discern any kinship with the iron discipline of those serialist masters. But Raskatov’s closed forms, whilst obvious, exert their own dramatic impetus in tandem with the events on stage, even if the vocal writing — melismata, scalic passages, and so on — swiftly becomes predictable. A passcaglia signals darkening of mood, likewise the odd Mussorgskian choral moment: again, perhaps, predictable, yet again, perhaps, ‘effective’: a word I recall my A-level music teacher counselling against using, but here undeniably ‘effective’.

Garry Walker’s command of the score sounded exemplary. The sweeping dramatic drive he imparted made me keen to hear him back at the Coliseum very soon. He certainly knew how to bring the best out of the excellent ENO Orchestra — who deserved a good number of cheers of their own. The musicians played their hearts out — perhaps an unfortunate metaphor in the context of the present work — so much as to make one tempted truly to believe in Raskatov’s score. Steven Page presented a convincing dramatic portrayal of Preobrazhensky’s dilemma: no hint of caricature here, though the vibrato may have proved a little much for some tastes. Peter Hoare did likewise, albeit in very different manner, for Sharikov, repelling and provoking sympathy. Other noteworthy performances included the aburdist coloratura part of Zina the maid (Nancy Allen Lundy) and the grotesque cameo of Frances McCafferty’s elderly Second Patient. How could anyone refuse? How could anyone not? The dog as dog has two voices: unpleasant, the distorted, loud-speaker-hailing soprano Elena Vassileva (also impressive as the professor’s housekeeper, Darya Petrovna), and pleasant, the fine counter-tenor, Andrew Watts. There was certainly no finer musicianship on stage than that of Watts, whose plangent tones inspired the most genuine sympathy of all without sentimentalising.

The theatre seemed full and the audience responded enthusiastically. I saw two composers — Raskatov aside — so I suspect there will have been more. So no, this was not a musical event to rank with the recent premiere of Alexander Goehr’s Promised End — English Touring Opera’s initiative rightly described by Michael Tanner in The Spectator as ‘astoundingly heroic’ — but as a musico-theatrical event, it scored very highly. Unlike, say, the dismal recent Rufus Norris Don Giovanni, which, had ‘theatre people’ come to see it, might well have put them off opera for life, this might just have intrigued some of them to explore musical drama further. Our political and financial masters would never understand this, let alone agree, but that is something to which one cannot affix a price.

Mark Berry

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DogHeart01.gif image_description=Steven Page as Professor Filipp Filippovich Preobrazhensky [Photo by Stephen Cummiskey courtesy of English National Opera] product=yes product_title=Alexander Raskatov: A Dog’s Heart product_by=Professor Filipp Filippovich Preobrazhensky: Steven Page; Peter Amoldovich Bormenthal: Leigh Melrose; Sharikov: Peter Hoare; Sharik the dog (unpleasant voice): Elena Vassileva; Sharik the dog (pleasant voice): Andrew Watts; Darya Petrovna: Elena Vassileva; Zina: Nancy Allen Lundy; Shvonder: Alasdair Elliott; Vyasemskaya: Andrew Watts; First Patient: Peter Hoare; Second Patient: Frances McCafferty; Provocateur: David Newman; Proletarians: Ella Kirkpatrick, Andrew Watts, Alasdair Elliott, Michael Burke; Fyodor/Newspaper Seller/Big Boss: Graeme Danby; Secretary: Sophie Desmars; Investigator: Matthew Hargreaves; Drunkards: Michael Selby, Christopher Speight. Old Women: Deborah Davison, Jane Reed; Puppeteers: Robin Beer, Finn Caldwell, Josie Dexter, Mark Down. Director, choreographer: Simon McBurney; Set designs: Michael Levine and Luis Carvalho; Costumes: Christina Cunningham; Lighting: Paul Anderson; Movement: Toby Sedgwick; Finn Ross (projections); Director of Puppetry: Blind Summit Theatre — Mark Down and Nick Barnes. Chorus of the English National Opera (chorus master: Martin Merry); Orchestra of the English National Opera; Garry Walker (conductor). Coliseum, London, Saturday 20 November 2010. product_id=Above: Steven Page as Professor Filipp Filippovich PreobrazhenskyAll photos by Stephen Cummiskey courtesy of English National Opera

Don Carlo, Metropolitan Opera, New York

By Martin Bernheimer [Financial Times, 23 November 2010]

Nicholas Hytner is a brilliant theatre director. But the demands of opera are quite unlike those of unsung drama, and his staging of Don Carlo - first presented at Covent Garden in 2008 and imported to the Met on Monday - is troublesome.

Tosca, Manitoba Opera

Puccini’s Tosca has everything: passionate love, consuming jealousy, undisguised lust, evil deceit, even murder and suicide. Manitoba Opera’s (MO) mostly Canadian cast rose to the occasion, leaving the audience emotionally spent but invigorated.

Conductor Tyrone Paterson led the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra from the pit in Puccini’s marvellously dramatic score that foreshadows much of the onstage action. Vigorous playing and superb solo section work throughout provided exactly the added finesse required, making this a first-rate performance.

Veteran director Val Kuinka worked her magic with the help of an exemplary cast. Wendy Nielsen as Tosca and Richard Margison as artist Cavaradossi outdid themselves, portraying the tragic figures with realism and relish. Margison hasn’t lost a step as his extensive career continues. With a tenor voice that’s easy to listen to, he floated effortlessly to his upper range in “Recondita armonia.”

His wistful rendition of the celebrated aria “E lucevan le stelle” in the final act almost broke our hearts, his powerful voice aching with love for his adored Tosca. Totally convincing and touching, Margison crafted this into a real tearjerker and the clarinet solo introducing it was splendidly sensitive, enhancing our anticipation of this favourite.

Talk about art imitating life! Nielsen was outstanding as Tosca — a great actress, putting her entire being into the demanding role of the opera singer title character. With her lovely, refined soprano, she lent her full vibrato and flexible style to the twists and turns of the plot, moving fluidly from jealous lover to desperate murderess. In “Non la sospiri, la nostra casetta,” she showed a diaphanous lightness to her voice, barely alighting on each note before flitting to the next.

Rich phrasing and fervent zeal highlighted her “Visse d’arte, vissi d’amore,” as she sang, collapsed on the floor, disconsolate and despairing, beseeching God for deserting her despite her lifelong piety and humanity. Nielsen is the consummate opera star, with a reliable, mature voice that is completely satisfying. Powerful beyond belief, her dramatic cries of pain reached right into the audience’s hearts.

Wendy Nielsen as Tosca and Richard Margison as Cavaradossi [Photo by R. Tinker courtesy of Manitoba Opera]

Wendy Nielsen as Tosca and Richard Margison as Cavaradossi [Photo by R. Tinker courtesy of Manitoba Opera]

Baritone Gaétan Laperrière returned to MO in the role of villainous chief of police Baron Scarpia. Dressed to the nines in black with gold braiding and trim, he looked every inch a self-indulgent scoundrel bent on getting his way. Yet Laperrière’s first entry was soft - barely discernible. His “Va Tosca!” was overly subtle, lacking power. And while his voice had agreeable resonance and flow, one wanted him to boom a little more, and strike fear into our hearts. Laperrière’s actions and words were suitably despicable, but his delivery belied his villainy. Frequent wooden movements were also questionable.

Peter Strummer’s droll Sacristan, on the other hand, was completely endearing. Announcing his arrival onstage with several healthy sneezes, he was a natural in this comic role. His bass-baritone made “E sempre lava!” a breath of fresh air before the drama to come. He has his gestures down to an art and gave us the only laughs of the evening.

Supporting roles by David Watson (Angelotti/Sciarrone), Keith Klassen (Spoletto) and Howard Rempel (jailer) were all solid and credible and Carson Milberg was a sweet-voice shepherd boy offstage. Acoustics can be tricky with offstage singing and it may be wise to station Milberg closer to the curtain to ensure the audience can fully appreciate this musical lad’s talents.

Wendy Nielsen as Tosca and Gaétan Laperrière as Scarpia [Photo by R. Tinker courtesy of Manitoba Opera]

Wendy Nielsen as Tosca and Gaétan Laperrière as Scarpia [Photo by R. Tinker courtesy of Manitoba Opera]

The chorus is not especially busy in Tosca but certainly came through well when called upon and costuming was truly impressive.

The three sets were amazingly ornate and detailed, transporting us easily to 19th century Rome, and but for some shaky spotlighting, Bill Williams lighting was mood-setting splendour.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tosca_tall_ManitobaOpera.gif image_description=Tosca poster [Manitoba Opera] product=yes product_title=Giacomo Puccini: Tosca product_by=Scarpia: Gaétan Laperrière; Cavaradossi: Richard Margison; Tosca: Wendy Nielsen; Sacristan: Peter Strummer. Director: Valerie Kuinka. Conductor: Tyrone Paterson. product_id=November 22, 2010

Loft and found: have you got a Vivaldi lurking in your attic?

By Tom Service [The Guardian, 22 November 2010]

Vivaldi. The world's most forgetful composer? Why on earth have so many of his manuscripts been turning up in obscure collections across the British Isles in the last couple of months? In October, it was a flute concerto called Il Gran Mogol ("The Great Mogul", if my Italian's up to snuff) discovered in the Marquesses of Lothian's family papers in Edinburgh, and this month, it's a couple of violin sonatas in a 180-page portfolio donated to the Foundling Museum in London, pieces that were probably originally written for amateurs, which could be heard for the first time in 270 years, played by La Serenissima in Liverpool on Sunday.

November 21, 2010

Adriana Lecouvreur, Royal Opera

Despite Adriana Lecouvreur being something of a rarity in the UK, having been absent from the stage of Covent Garden for more than a century, the prospect of Angela Gheorghiu taking on the title role for the first time was more than enough to justify the risk — though it is perhaps a sign of the times that it is a co-production with four other international houses, the largest number of collaborators I can ever recall seeing in an opera programme.

If I were producing an opera about theatre and actors, David McVicar is precisely who I would engage to direct it, given his knack for injecting opulent theatricality into the most naturalistic of dramatic situations. And if nobody had told me that this was one of his, it wouldn’t have been difficult to guess. The hallmarks were all there — the vast crowd of supernumeraries, the stage clutter, and Brigitte Reiffenstuel’s deconstructed-Baroque dance costumes to name but a few — but this time McVicar has gone one step, if not many steps further in the name of making a point about the nature of theatre and artifice.

Jonas Kaufmann as Maurizio

Jonas Kaufmann as Maurizio

It was heaven for a geek like me, thanks to the sheer number of references

to other shows — maybe a natural progression from the score itself. Cilea

was a contemporary of Puccini and Massenet, and most of the aural reminders are

from this milieu, but Act 4 in particular evokes a wider range of influences.

In McVicar’s staging, a balletomane friend of mine who attended the dress

rehearsal picked up on direct references (costumes and choreographic devices)

within the Act 3 ballet to Royal Ballet productions of La fille mal

gardée, Invitus Invitam and Sylvia. The chorus crowded

into their onstage audience-seating much as they did in McVicar’s

Alcina for ENO in 1999; then, a marble bust of Handel dominated the

stage; here the bust was Moliere’s. It was interesting that of all his

own works, this was the one McVicar chose to reference; another opera about the

blurred boundary between theatre and reality.

With Charles Edwards’s set dominated by a large box which for much of the opera served as a full-height, fully-formed stage-within-a-stage, the production seemed determined to underline that we were the audience, and what was happening before us was not reality. The mostly naturalistic scenery was garnished with little touches of artificiality; vividly ornate interiors, for example, were finished off not with heavy velvet draperies, but with curtains painted onto wooden flats. Even Act 2, whose stage directions contain no overt references to a theatrical setting, appeared to be taking place on a stage, with the men in particular giving a stylised feel to their entrances and exits. Only in Act 4 was this extra level of artifice dispensed with; though the spectre of the stage continued to loom large over Adriana, it was a bare shell, and suddenly (the ludicrous business of the poisoned violets notwithstanding) it was all a lot more immediate and credible.

So what of the much-hyped cast? Gheorghiu may not be an immediately obvious ‘humble handmaid of art’ but she was poised and charming, playing a very youthful version of this heroine who historically has been associated with the ageing diva. Her voice is very much on the small side given the scoring, and for the intimacy of the first and last acts (which frame Adriana’s two celebrated arias) it was often exquisite. But in the confrontation with the Princesse de Bouillon and again in her vengeful Phèdre monologue, Gheorghiu was a kitten when a tigress was needed. I can’t quite picture how she will hold her own when the role of the Princesse transfers to the mighty Olga Borodina later in the run.

Jonas Kaufmann always seemed on the edge of something spectacular, and the contained restraint with which he treats his large, dark-coloured voice would have been massively exciting had it been part of a broad palette. As it was, he seemed to be trying to demonstrate that a hot-blooded verismo hero can be sung with subtlety and intelligence, while also showing off some of his remarkable technical skill (particularly in his legato, and once, memorably, his impeccable ability to diminuendo on a top note). It was very, very impressive — but all too careful, too measured. It seemed a studied effort in avoiding stereotype (or perhaps he was reining himself in to avoid overpowering Gheorghiu) but I longed for him to let rip.

- Michaela Schuster as Princesse De Bouillon and Bonaventura Bottone as Abbé De Chazeuil

- Michaela Schuster as Princesse De Bouillon and Bonaventura Bottone as Abbé De Chazeuil

Michaela Schuster was a dramatically-committed if somewhat vocally undisciplined Princesse, though it was a misjudgement (probably the director’s) to have her exchange with Adriana in Act 3 played partly for laughs, which diminished the impact. Alone among the major principals, Alessandro Corbelli — as Adriana’s unrequited admirer, Michonnet — was alone in painting a full and touching character portrait.

Much of the interest, and there was plenty, came from the supporting characters. Janis Kelly (Mlle. Jouvenot) and Sarah Castle (Mlle. Dangeville) sparked off one another in Act 1 in an impeccably-judged battle of wills; Bonaventura Bottone (the Abbé de Chazueil) and Maurizio Muraro (the Prince de Bouillon) gave nicely-detailed character portraits in a production which made them quite stylised and more than a little camp.

Mark Elder’s conducting displayed many of the same characteristics as Kaufmann’s singing — lovely, delicate, but for this repertoire far too careful and finely-crafted. On opening night the Gheorghiu and Kaufmann fans were out in force, with every aria met with cheers. But for me, a bit less decorum and a lot more scenery-chewing, both on stage and in the pit, would have served the opera better, and improved a promising performance in a lovingly-crafted production immeasurably.

Ruth Elleson © 2010

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ADRIANA-2442-0317-GHEORGHIU.gif image_description=Angela Gheorghiu as Adriana Lecouvreur [Photo by Catherine Ashmore courtesy of The Royal Opera] product=yes product_title=Francesco Cilea: Adriana Lecouvreur product_by=Adriana Lecouvreur: Angela Gheorghiu, Ángeles Blancas Gulín; Maurizio: Jonas Kaufmann; The Prince of Bouillon: Maurizio Muraro: The Princess of Bouillon: Michaela Schuster, Olga Borodina; Michonnet: Alessandro Corbelli; L'Abbate di Chazeuil: Bonaventura Bottone; Poisson: Iain Paton; Quinault: David Soar; Madame Jouvenot: Janis Kelly; Madame Dangeville: Sarah Castle. Conductor: Mark Elder. Director: David McVicar. Set designs: Charles Edwards. Costume designs: Brigitte Reiffenstuel. Lighting design: Adam Silverman. Choreography: Andrew George. product_id=Above: Angela Gheorghiu as Adriana LecouvreurAll photos by Catherine Ashmore courtesy of The Royal Opera

The Met’s Don Pasquale: A treat for the eyes, a feast for the ears

By David Abrams [CNYCafeMomus.com, 21 November 2010]

No one knows whether W.C. Fields was thinking of Don Pasquale when he delivered the phrase, "never give a sucker an even break." But when it comes to the plot of Donizetti’s farce, the celebrated American comedian was right on target.

November 20, 2010

The Makropulos Case in San Francisco

Specifically she kicked the asses of the several men who materialized in her long, long life just as the effects of the longevity potion her father invented back in 1593 began to wear off. These unfortunate men had awakened those few moments when, over the centuries, her soul had been moved, and these rediscovered feelings conflicted with her instinct for eternal life as she had come to understand over the centuries the futility of her emotions. She finds resolution of this conflict in death.

This bizarre masterpiece is, all said and done, Janáček’s idea of a comedy. His uniquely middle European depressive poetic, melding philosophy with highly complex emotions took solid hold into the reaches of War Memorial Opera House by its third performance (November 17).

Universally vivid performances. Elina’s great, great, great, etc., grandson Berti sung by Slovakian tenor Miro Dvorsky touched the true tonalities of the Czech language, the Prus of German bass-baritone Gerd Grochowski found the suavity and confidence of an Austro-Hungarian aristocracy, the fumbling lawyer Dr. Kolenaty was enacted skillfully by stalwart San Franciscan buffo Dale Travis.

Karita Mattila as Emilia Marty and Gerd Grochowski as Jaroslav Prus

Karita Mattila as Emilia Marty and Gerd Grochowski as Jaroslav Prus

Touching were the performances of Adler alumni Thomas Gleen as Vitek and Brian Jagde as Janek, the callow young victim of Elina’s perfected sexual prowess. Adler alumnus Matthew O’Neill was caricatural pure perfection as Elina’s idiot lover Hauk, as was Kristina, the opera-star-to-be (Elina Makropulos’ protege) sung by Susannah Biller.

Dominating the stage equally were Janacek’s heroine Karita Mattila as Elina Makropulos and Janáček’s orchestra conducted by Jiří Bělohlávek. They were simply one and the same, one soprano embodying Mo. Bělohlávek’s seventy-three players. Yes, the performance was huge. She was huge, the enormity of 337 years of life graphically unravelling on the stage was quite real.

The story of Elina Makropulos is told musically rather than dramatically, the little lawsuit Gregor vs. Prus merely pretext for the inner life of Mme. Makropulos to explode in the orchestra, superseding the dramatic inconsistencies and general confusion of the libretto.

Mme. Mattila absorbed every musical movement in a dramatic performance so complete that it will become legendary as it traverses the world. For this she has partnered with conductor Bělohlávek who revealed the gamut of the depraved humanity Janáček had transformed into pure music in his preceding oeuvre. Like all Janáček heroines Elina Makropulos too attains a sort of salvation by reconciling herself to the futility of life and therefore accepting death.

Miro Dvorsky as Albert Gregor, Karita Mattila as Emilia Marty and Dale Travis as Dr. Kolenatý

Miro Dvorsky as Albert Gregor, Karita Mattila as Emilia Marty and Dale Travis as Dr. Kolenatý

The production by Viennese director Olivier Tambosi merely supported the Mattila performance, the stylishly directed supporting cast moving appropriately over the turntable set imagined by big-time designer Frank Philipp Schlössmann. Like the staging the set disappeared behind the Mattila performance. Its cartoon lines were self-consciously descriptive of a caricatural concept that the production flirted with but never fully absorbed. Maintaining this careful balance of caricature and expressionist comedy was however the strength of the production, allowing at least some perspective for the over-the-top Mattila performance.

*“Let’s kick ass” was Mme. Mattila’s term before attacking Salome last year on the Met’s Live in HD.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mattila2.gif

image_description=Karita Mattila as Emilia Marty [Photo by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Leoš Janáček: Věc Makropulos [The Makropulos Affair]

product_by=Emilia Marty: Karita Mattila; Albert Gregor: Miro Dvorsky; Baron Jaroslav Prus: Gerd Grochowski; Dr. Kolenaty: Dale Travis; Vitek: Thomas Glenn; Kristina: Susannah Biller; Count Hauk-Šendorf: Matthew O’Neill; Janek: Brian Jagde; A Stagehand: Austin Kness; A Chambermaid, A Cleaning Woman: Maya Lahyani. Conductor: Jiří Bělohlávek. Director: Olivier Tambosi. Production Designer: Frank Philipp Schlössmann. Lighting Designer: Duane Schuler.

product_id=Above: Karita Mattila as Emilia Marty

All photos by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera

November 19, 2010

Carmen, Arizona Opera

All of the action was moved into a bullring with choristers and even some audience members sitting above it in the arena seats. Uzan and Michael Baumgarten designed the scenery. Patricia A Hibbert created the period costumes and in Arizona, stage director Kay Walker Castaldo told the story in a more or less straightforward manner. Thanks to Baumgarten’s atmospheric lighting, one could imagine Lillas Pastia’s Tavern or a mountain pass on a dark night inside that bullring.

Artistic Director and Principal Conductor Joel Revzen led the Arizona Opera Orchestra in a brisk and powerful rendition of the score. The Carmen and Don José on Saturday evening were American mezzo-soprano Beth Clayton and Mexican tenor Fernando De La Mora. Clayton had considerable difficulty in the first act and her Habanera was sometimes out of tune but her seductive looks worked their magic on much of the audience. De La Mora has a robust voice and he used it to excellent effect. Both vocally and physically, he was a strong, virile lover.

Jossie Perez [Photo courtesy of Columbia Artists Management Inc.]

Jossie Perez [Photo courtesy of Columbia Artists Management Inc.]

Sunday afternoon’s cast offered Puerto Rican mezzo-soprano Jossie Perez as

Carmen and American tenor Garrett Sorenson as Don José. Perez is a sex kitten

who sings with colorful chest tones so she makes a fine Carmen. Sorenson, a

tenor with an exciting sound, was a dramatic José whose Flower Song garnered a

number of bravos. He is definitely a singer to watch. Another new singer who may

have a good career ahead of her is the radiant-voiced Janinah Burnett. Her

Micaëla was a brave young woman who tried her best to save José and sang her

aria with floods of iridescent tone.

Mexican baritone Luis Ledesma looked totally authentic as Escamillo, the bullfighter, and he sang with a strong polished sound. Peter Volpe was a stentorian Zuniga who commanded the stage. Studio members Cameron Schutza and Kevin Wetzel were eminently praiseworthy as El Remendado and El Dancaïro. Their feminine counterparts Rebecca Sjöwall and Stephanie Foley Davis suffused their phrases with emotion as Frasquita and Mercédès. Sjöwall has lovely high notes and they were most welcome in this opera where the title role is sung by a mezzo.

This production contained a good bit of Flamenco and ballet featuring Dance Captain Adam Cates and a group of nine powerful but graceful dancers. Peggy Hickey’s choreography evoked many images of France and Spain, even bringing to mind a painting or two. The performances of this Carmen next weekend in Phoenix should be a most worthwhile addition to the city’s fall season.

Maria Nockin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Beth-Clayton-as-Carmen.gif image_description=Beth Clayton as Carmen [Photo courtesy of http://www.bethclayton.info] product=yes product_title=Georges Bizet: Carmen product_by=Carmen: Beth Clayton (November 13, 19, 21), Jossie Perez (November 14, 20); Jose: Fernando de La Mora (November 13, 19, 21), Garett Sorenson (November 14, 20); Micaela: Janinah Burnett; Escamillo: Luis Ledesma; Zuniga: Peter Volpe; Frasquita: Rebecca Sjöwall; Mercedes: Stephanie Foley Davis; Remendado: Cameron Schutza; Don Cairo: Kevin Wetzel; Morales: Kevin Wetzel. Conductor: Joel Revzen. Director: Kay Walker Castaldo. product_id=Above: Beth Clayton as Carmen [Photo courtesy of http://www.bethclayton.info]Il Viaggio a Sicilia

Happily, once inside this spectacular architectural marvel, the production of Don Quichotte was similarly chockfull of awesome surprises and considerable beauty.

Palermo, to be sure, is one of Italy’s leading companies and they stake their reputation on a well-considered mix of tried and true stars, standard and adventurous repertoire. In this instance, they began by engaging the world-renowned director Laurent Pelly to work his magic with a lesser Massenet opus, one more famed in our imagination as the Cervantes source story than this diluted French opera rendition. As a piece of composition the work is curiously paced, at times rip-snorting, more often gently introspective as dictated by the librettist’s erratic choices of which iconic episodes to feature and, more telling, which to omit.

Mr. Pelly’s fertile imagination is fully engaged here, and he made me believe this is a more significant opera than it really is. His overall concept centers around the conceit that Massenet himself is onstage as the protagonist and he morphs into Quixote as he pens the work. He was ably supported by the ingenious scenery created by Barbara de Limburg Stirum. She featured heaping mounds of manuscripts that first formed a staircase of sorts to Dulcinée’s balcony, and later actually created the massive rolling hills of the countryside. Highly impressive and impressionistic, this proved a perfect complement to the score’s aural palette.

Pelly not only masterfully moved the large chorus through meaningful staged numbers, but maintained exceptional focus on the interaction of his principals. The fluidity of crowd scenes and the clarity of the story-telling were always infused with generous heart and good dramatic purpose. And wit. Let us not forget wit. To wit:

The famous “tilting at windmills” was arguably the visual highpoint of the night. First, a windmill blade flew in from on high, then another unfolded from it and in a twinkle there was a dazzling windmill in full rotation. But unlike, say, Man of La Mancha which relegates the actual battle to an offstage moment, Laurent and Barbara contrived a sensational visual effect, having Quixote first settle into what looks to be a rocky seat that is part of the landscape. But, whoa Nelly, this seat soon pokes forward from the hillside on a giant arm bearing our hero aloft toward the slicing blades. But that’s not yet all. It then begins a crazed dip-and-soar like the old Octopus ride at the county fair. It was so dazzling that it became a hard act to follow.

Irini Karaianni as Dulcinée and Ferruccio Furlanetto as Don Quichotte

Irini Karaianni as Dulcinée and Ferruccio Furlanetto as Don Quichotte

But the team had more in store. Act IV featured an extensive terrace and staircase placed neatly atop the hillside of papers, and was fleshed out with other highly evocative images such as having Dulcinée dance with three men sporting tall, skinny horse head masks/hats. Not only powerful sexual imagery, but also a nice touch of spice to flavor the drawn out conflict in the scene. If I had one wish scenically, it would be that they not have taken time to close the curtain, remove the terrace and restore the hills to their previous unadorned state for Act V. It took the dramatic momentum away when the piece could least afford it, and visually it did not make any notable effect.

Oddly, the director has the leading man die standing up, albeit leaning, skewed at an angle, obviously braced somehow. He was beautifully lit in a pool of golden light (did I mention the excellent, ever shifting lighting was by Joel Adam?) but I wondered if the effect was worth the effort or worth the wait. This production was shared with Brussels’ Theatre Monnaie/DeMunt, and re-staged by Diane Chèvre-Clément. Should it be re-mounted, I might suggest they simply pull Quixote and Sancho in front of the act curtain seamlessly after Act IV, light them in isolation, and just let Act V continue the emotional momentum and limpid musical atmosphere.

Evergreen bass Ferruccio Furlanetto showed splendid command of all his resources here, and his Don was noted for an outpouring of burnished tone, heartfelt phrasing, comic abandon (with no trace of buffoonery), and very decent French to boot. He effortlessly carried the show as any good Quixote must. And he was matched every step of the way by Eduardo Chama’s lively rendition of Sancho Panza. Mr. Chama has a bright, well-placed baritone that has good ping and responsive technique. He was a perfect foil for Mr. Furlanetto and the two set off dramatic sparks on many occasions. Too, Eduardo communicated a touchingly simple admiration for his master that illuminated every bit of pathos that Massenet intended. Furlanetto and Chama were a wholly winning, first-rate combination.

In the less well-written female role, the fetching Irini Karaianni brought much visual and aural pleasure to the proceedings with her quite bewitching Dulcinée. Her smoky mezzo has a hint of darkness overall, but the highest notes slipped into a rather bright upper extension. She does not press her chest voice, but nevertheless commands a decent amount of presence in the lower extremes. It is to her credit (and Pelly’s) that Ms. Karaianni manages to bring sympathy and a third dimension to one of the repertoire’s thinnest sketches of a character. The remaining quartet of principals was well-cast with Elisabetta Martorana a silver-voiced Pedro; Rachele Stanisci a persuasive Garcias; Salvatore Ragonese a secure Rodriguez; and first among equals, Gianluca Sorrentino, a honey-toned Juan.

Alain Guingal conducted lovingly and with such knowing detail that he seemed to wholly believe Don Quichotte is the masterpiece it isn’t. His players responded in kind with beautifully atmospheric ensemble work and solo passages ripe with musical personality. In a work that often relies on diffuse, languid effects Maestro Guingal found freshness and a pulsating arc from the first downbeat to the final cut-off. In tandem, Andrea Faidutti’s well prepared chorus sang cleanly even when frequently moving about in (slightly over-)choreographed scenes.

Teatro Massimo

Teatro Massimo

On the other side of the island, Catania’s Teatro Massimo Vincenzo Bellini was taking no chances with such novel repertoire, opting instead for a wholly competent La Bohème. The company seems to favor double- and even triple-casting the leads during the run, with an eye to including a handful of performances featuring a major star. In this case, that would be Sicilian Marcello Giordani’s Rodolfo.

Mr. Giordani is a known commodity, of course, a tenor whose substantial lirico-spinto voice is wedded to a reliable technique, persuasive stylistic acumen, ringing power, and sound delivery. Having brought his Rodolfo to many of the world stages, he knows this part inside out, and sings it exceedingly well. Would it be carping to say I would have appreciated even more a bit of spontaneity in his portrayal? Or a little more gradation of volume below a standard mezzo forte?

The first surprise of the evening to me was the young baritone Vincenzo Taormina as Marcello. Mr. Taormina has a rich, robust baritone of uncommon beauty and substantial power; unaffected stage presence; and possesses a fine understanding of the nuance of musical and dramatic effect that can be found in any role. He was easily Mr. Giordani’s equal and their Act IV duet was a high point of the evening. Vincenzo also has the benefit of conveying a youthfulness that was at odds with his other “young” Bohemians. To be fair, Fabio Previati’s well-sung Schaunard was almost as believable, but Alessandro Busi seemed miscast as Colline at this point in his career. His singing was sincere and secure enough, although veering a bit off-pitch in the upper stretches of the Coat Aria. But although he threw himself into the camaraderie completely, visually he looked as out of place as a fifty year old in the Student Union cafeteria.

The show’s major revelation was Donata d’Annunzio Lombardi as Mimi. Hers is a beautifully schooled soprano, capable of all the requirements Puccini sets out for his heroine. Conversational, introspective musings? Check. Ability to soar over the amassed vocal and instrumental forces? Check. Skill in floating delicate, secure, melting notes? Check. She may have a bit more edge than other recent definitive Mimi’s like Freni and Scotto. But Ms. Lombardi definitely has all the goods, not only for Mimi, but Butterfly and Liu and, and, and. Watch for her as her star continues to rise.

Sabrina Vianello contributed the sort of chirpy, light-voiced Musetta that we hardly ever encounter nowadays. Perhaps she brought more stage savvy and spunk than middle voice to the part, but she was always entertaining and, in the final scene, moving. The treasurable comprimario Angelo Nardinocchi did effective double duty as Benoit and Alcindoro (the former in as ill-fitting a skull cap as I hope to never see again).

In the pit, conductor Carlo Rizzari got everything settled down after a clumsy start. The band began out of sync for the first few bars, then plodded through a generally uninvolved, overplayed first act. But lo, once past a couple of minor ensemble hiccups in Act Two, the maestro and the orchestra seemed to relax, breathe with the singers, and go on to some truly luminous playing in the second half the show. Tiziana Carlini had prepared her large chorus well, and the children were especially effective.

Director Roberto Laganà Manoli (also costume designer) and set designer Pierluigi Samartini generally played it safe with a pleasingly traditional, no nonsense mounting that punched all the right tickets. And why not? Left alone, in the hands of such wonderful artists, it pretty much plays itself. Not to say that Signor Manoli didn’t have a trick or two up his sleeve. Marcello is discovered at curtain rise on a mini scaffold painting a rather large canvas with (what I presume is) a witty nod to the opening of Tosca. When Colline bursts in with his booty in Act I, it is so substantial that three delivery boys have to help carry it in. The amassed choral forces at Momus were well managed, especially the positioning of hen well-tutored youth who were heard to maximum advantage.

On a few occasions there were misfires. An odd positioning of actors and indecisive spatial considerations made for an awkward hand holding set up to “Che gelida manina.” And some of Three was place too extremely left or right so as to render singers momentarily out of sightlines for a third of the audience. Too, while the sets were pleasant, it took way too long to change them, with the combined intermissions being longer than the piece itself.

Still, the SRO audience did not seem to care, and lingered long after curtain fall in the beautiful auditorium (one of Europe’s loveliest) to lavish the performers with extended ovations.

James Sohre

Cast lists:

Don Quichotte

Dulcinée: Irini Karaianni

Don Quichotte: Ferruccio Furlanetto

Sancho: Eduardo Chama

Pedro: Elisabetta Martorana

Garcias: Rachele Stanisci

Rodriguez: Salvatore Ragonese

Juan: Gianluca Sorrentino

Conductor: Alain Guingal

Director and Costume Design: Laurent Pelly

Set Design: Barbara de Limburg Stirum

Lighting: Joel Adam

Restaged by Diane Chèvre-Clément

Chorus Master: Andrea Faidutti

Co-production with La Monnaie-De Munt, Brussels

La Bohème

Mimi: Donata d’Annunzio Lombardi

Rodolfo: Marcello Giordani

Musetta: Sabrina Vianello

Marcello: Vincenzo Taormina

Colline: Alessandro Busi

Schaunard: Fabio Previati

Benoit/Alcindoro: Angelo Nardinocchi

Parpignol: Michele Mauro

Conductor: Carlo Rizzari

Director and Costume Design: Roberto Laganà Manoli

Set Design: Pierluigi Samartini

Lighting Design: Salvatore Noè

Chorus Master: Tiziana Carlini

image=http://www.operatoday.com/TMassimo-Don-Quichotte-FOTO.gif

image_description=Ferruccio Furlanetto as Don Quichotte [Photo courtesy of Teatro Massimo]

product=yes

product_title=Il Viaggio a Sicilia

product_by=See cast lists below

product_id=Above: Ferruccio Furlanetto as Don Quichotte

All photos courtesy of Teatro Massimo

November 18, 2010

Karita Mattila: Helsinki Recital

Besides the DVD of the full recital and encores, Ondine provides a second disc basically constituting a sampler of studio Ondine recitals from the 1990s. Ms. Mattila is in gorgeous voice in these earlier recordings, singing Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms with exquisite tone and reserved but affecting emotion, and pouring out idiomatic splendor in songs from countrymen Jean Sibelius, Toivo Kuula, and Erkki Melartin (with Ilmo Ranta at the keyboard).

But does Ondine do any favors to Ms. Mattila with the inclusion of this second disc? The voice in the 2006 recital is not the same liquid, flexible instrument heard ten years earlier. The Finnish National Opera house looks to be a relatively intimate concert space, but it’s still a hall, as opposed to the confines of a recording studio with sensitive equipment that allowed Mattila to employ a wide range of dynamic effects. The opening set of the 2006 recital, Duparc songs, often finds Mattila’s voice hardening by the middle of a song, and even a sort of Slavic thickness developing. This is less of a hindrance in the Kaija Saaraiho set “Quatre instants,” dedicated to Ms. Mattila. Here the soprano’s instrument is put to more dramatic, mechanical use. Martin Katz gets to shine in the Saaraiho music, and the director often focuses on the pianist's hands at the keyboard as he deals with wild jumps, booming bass lines and skittering steps across the high keys. At the end of the set Ms. Mattila clutches the score to her chest and then welcomes the composer to the stage. It must be quite an honor to have a preeminent contemporary composer fashion a piece for oneself; nonetheless, anyone who wants to hear this set of songs more than once has a greater appetite for the gnarly and self-consciously arty than your reviewer does.

The second half makes for a more enjoyable experience, with that Slavic tinge put to fine use in some lovely Rachmaninoff settings and then the Dvořäk “Gipsy Songs.” Your reviewer actually saw a 2003 recital appearance by Ms. Mattila, in a shamefully under-attended recital at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles back in 2003. The program was virtually the same, only with the cherishable exception of Sibelius songs in place of the not-yet-completed Saaraiho. As fine an actress as Ms. Mattila can be, she does enjoy well-considered effects, and after a few years of doing this recital set, it seems fair to say that any spontaneity has gone out of the evening. She did the same tacky but fun encore back then (Victor Young’s “Golden Earrings”), as well as the sweet Finnish traditional that closes the evening. In Helsinki Ms. Mattila looks stunning, it should be noted, almost uncomfortably smooth-faced and glamorized in hair and make-up. The porcelain surface of her face barely creases, no matter how much effort she brings to certain passages.

Ondine’s presentation is immaculate, and the camerawork couldn’t be better, as we enter the gorgeous Helsinki house form outside and see the handsome crowd gather in the lobby, champagne glasses in hand. Your reviewer would have preferred subtitles to the translated texts in the booklet, but some people love nothing more than to rustle programs at a recital, so here’s their chance to do it at home.

If the DVD recital slightly disappoints, therefore, rejoice in the artistry caught forever in the bonus disc of Ms. Mattila’s 1990s recordings.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ondine_ODV4004.gif

image_description=Karita Mattila — Helsinki Recital

product=yes

product_title=Karita Mattila — Helsinki Recital

product_by=Martin Katz, piano; Karita Mattila, soprano; Ilmo Ranta, piano

product_id=Ondine ODV 4004 [DVD plus bonus CD]

price=$33.49

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=504927

The Forthright Tenor

By David Mermelstein [WSJ, 18 November 2010]

All opera stars endure the burden of expectation, but Roberto Alagna has felt that weight keenly. Dubbed "the fourth tenor" early in his career by unthinking handlers, he has found it difficult to shake unfair comparisons to Plácido Domingo, José Carreras and the late Luciano Pavarotti, none of whom he is heir to. Moreover, he has sometimes chosen parts that are too heavy for his essentially lyric voice. Yet he airily dismisses such concerns as he readies for the daunting title role in the Metropolitan Opera's new production of Verdi's "Don Carlo," which opens Monday.

Stellan Sagvik: An Interview

In addition to all this Sagvik devotes himself to producing and releasing recordings of contemporary Swedish music on the label he founded, Nosag Records. We spoke by Skype on March 29, 2010.

TM: Where were you born?

SS: I was born in 1952 in a little town called Örebro, in the middle of southern Sweden, but moved from there when I was only four years old in 1956, so I have no memories whatsoever from that time. I grew up mostly in Stockholm.

TM: Were there musicians in your family?

SS: Not really. On my father’s side they had good singing voices. My grandfather, I think, played the flute, and one of my cousins played the guitar and was also a piano builder. Not really any musicians, and no composers whatsoever. On my mother’s side everybody is tone-deaf.

TM: Including your mother?

SS: Including my mother. She cannot sing two notes in a row.

TM: How did you get started in music? With an instrument? Or was it singing?

SS: I am told that when I was little I was sitting behind a big armchair pretending that I was a little radio. I don’t know how old I was at the time — maybe four or five. I was singing and making music — hitting some cans, or drumming on a stool. If you are talking about real music, I started playing recorder, as most children do in Sweden, at about six or seven. But then I thought that the songs in the recorder book were tedious and not very interesting, so I wrote my own. I was not a wonder-child — my mother kept them, and still has them, and they were random notes on lines on the paper.

TM: I suppose that when you were pretending to be a radio that the family did not yet have a television.

SS: Yes — there were no televisions in Sweden until the very late fifties, and early sixties. I saw a television for the first time in my life when I was seven. It was a big thing — some people had televisions. My mother said “It won’t be in our lifetime” that we would get a television.

TM: Was the broadcasting service through the government?

SS: In Sweden we have a rather unusual system. It is only very recently that we got commercial radio. Before that it was not government radio — it was owned by the unions — working people owned the system of radio and television in Sweden. The state was a not an owner — they had some involvement on the boards. It was ten to fifteen years ago that commercial radio got started in Sweden.

TM: What sort of music were you listening to on the radio?

SS: When I was little, there was very little music. There was one “Gramophone Hour” a day. The rest was talking, talking, talking, talking. There were some concerts on Saturdays, but I was too little. Once I was aware of what music was, when I was ten or eleven, there started to be more music being broadcast on the radio, and there was also a second station — there had been only one at the beginning. The second one was filled with music. When I was fifteen, they started a third channel with pop music. That was terrible! according to most people, but I thought it was rather OK.

TM: You were playing recorders with the other schoolchildren. Did you move on to other instruments?

SS: Not at the beginning. I was eleven or twelve when I started to play saxophone, which I played for a couple of years, but I thought it was a very heavy thing to carry that big box around, so I started taking leave. I would leave the house with my saxophone, tell my mother I was going to my lesson, and never went to the lesson, so my teacher called my mother after a couple of weeks asking where I was. She wondered “what is this???” since every week I had been going to the lesson, but I had been walking around with my big box, doing nothing. So I was not very interested at that time. I started really to take it more seriously when I was fifteen. I had a girlfriend at the time who was playing violin, both folk music and classical music. She took me to concerts — there were free concerts for youngsters at the concert hall at the time. She took me there, and I started getting interested. I also got some records. I got my first LP from my mother’s boyfriend (my father had died when I was little). He gave me an LP with the Beethoven fifth piano concerto. He was not a very nice guy — he bought it because he wanted me not to listen to pop music. It was a sort of kick in the ass — instead of buying Beatles or jazz he bought me Beethoven, and thought I would be mad. But I enjoyed it. By the end I knew every note because I listened to it all the time. When I started the relationship with this girl, I was fifteen, and began to write some music for her violin. I remember that I drew lines on a normal blank sketchbook, the sort you use for drawing, and I started writing a piece that later became a canon for two violins. At the time it was for solo violin — that was my first piece, from about ’67, ’68.

TM: Had you been studying music theory in school?

SS: Nothing like that. Again, it was this girlfriend that inspired me to start thinking about maybe getting some education in music, because I was very bored with school at the time, and wanted to quit. I was thinking about different ways to turn, and she said “Why don’t you go to the music school and see if they have some courses?” I met a very nice man, who quoted Handel, and said you have to learn everything that there is, and then go your own way. I took his advice, and started playing clarinet, since I still had some technique remaining from the saxophone. I had a very nice teacher who helped me to see music as expression, not only as notes that you have to manage with your instrument, but also something that you can speak with. You can tell something, tell stories, express feelings…. That’s how it all started, and just kept on rolling. I did a lot of work in theaters in my youth, so now I play almost all the instruments that there are. It sounds strange, but I play almost everything — I am not an expert on any of them, but I know how they all function, I can play tunes, I can use them for world music — for that type of concert.

TM: It’s much easier to write for them if you know what they do well, and what they don’t do well.

SS: Of course -and how they sound in their various registers, and what they shouldn’t do. You cannot write for a trombone in the same way that you write for a clarinet, and yet people who are writing with synthesizers don’t realize this — they write the same thing, regardless of what instrument it is for. But you have to think of this all the time.

TM: This is what Telemann said — that you must give the instrument what it likes to do, and that way the players will be happy, and you will be too.

SS: Absolutely. If you don’t write something that puts down or diminishes the musician, the musician does much better work, because they feel that you are using their skills, their musicality — you don’t insult them by coming with stupidities. I always have in mind that you have to work with the musicians, not against them.

TM: What was the musical environment when you were taking up the clarinet? Certainly there was rock and roll, and jazz, and contemporary music going on in Stockholm.

SS: Like most of my generation the basics were pop music — we didn’t call it rock, we called it pop. What Michael Jackson was doing is now called pop, while what we called pop is now rock. Most young people listened to Merseybeat, but I was more interested in those who were not doing the middle-of-the-road stuff — I wanted music that was more developed, that used more resources, perhaps worked with orchestras, did longer suites — not just two or three minutes, but six or seven or eight. That was what I listened to. When I got older — fifteen, sixteen, seventeen — I started listening to experimental groups like Parsons, King Crimson, Zappa….

TM: You mentioned your canon for violins. Where did you go after that in terms of the music that you were writing?

SS: I tried almost all types of ensembles, and sizes — my third or fourth pieces was my first symphony. For example, I read that there several types of clarinets — A, B-flat, C, D, E-Flat, F, A, A-flat — I used all of these in my symphony, and I also used the bassett-horn, that was not so common at the time, and also alto clarinet, and bass clarinet. It sounds like a clarinet symphony — that was not the case — but for every movement I changed the tuning for the clarinets, because I wanted to I see if the D clarinet had a different sound than the B-flat clarinet. Of course it does, but nobody ever played the symphony, so I didn’t get to hear the difference, and I don’t think people would be able to get access to all those different instruments.

TM: Where did you go to study music formally?

SS: That was rather late — I was twenty-four when I started higher education in music. I played clarinet, I played flute, I played oboe, I played several instruments — but I was not really any good compared to those that specialized in one. I played all the instruments, and so I couldn’t specialize in any, and couldn’t pass the entrance exam. When I did enter higher education, I did so as a composer, and not as an instrumentalist. This was in ’75 that I started.

TM: At the college of music in Stockholm?

SS: I slipped in — that’s my theory, anyway. There was a new professor of composition that year, and I had a very good recommendation from the boss where I had worked. He was a well-known director, and a well-known personality in Sweden. His

recommendation rather impressed the professor, so that’s why I got in so easily as a composer.

TM: You had been working at the theater?

SS: I had written pieces for the plays at the theater, and played many instruments. The director put all this in the recommendation. By this time I had already written about fifty pieces.

TM: Who was the professor with whom you went on to study?

SS: Gunnar Bucht, who was born in ’27, I think. He was professor for ten years, and then became headmaster of the college and the university and so forth. As a composer and a teacher he is very academic — very strict and filled with rules. He told that I would go through the program pretty much undisturbed, but that he thought that I could prune a little in my exuberantly growing garden. He thought that I had too many ideas, and his main aim was to try to get me to focus on few ideas, and develop them more.

TM: What was his background in terms of pedagogy?

SS: He had studied in Germany with a serial composer, I don’t remember who, and had also had lessons from Blomdahl and Rosenberg.

TM: The music you were writing was not twelve-tone….

SS: I did some pieces, but mostly as spin-offs from my professor’s assignments. Some of them I reused in pieces later, but I was never much into this…I thought it was a waste not to use the music which I had done — I tried to reshape it and make it useful. I made a flute concerto, the first one, and a piece for flute and organ, which were twelve-tone. The flute concerto I wrote when I was nineteen, and finished it with this professor. The piece was really finished already in ’72, but I reshaped it a little — shrunk it from big orchestra to flute and strings only.

TM: Would you say that you are self-taught?

SS: No, I wouldn’t, because in spite of what I said earlier, I got quite a lot from Bucht, because he made me more aware of what I was doing. I had lots of ideas, and wrote a lot of music, but based on intuition and not so much on thought. He made me focus so that I was aware of what I was doing, and why. I won’t say that the music that I did before was very much different from what I did after, but at least I felt more in control after my education.

TM: What would be a typical work from the time when you were studying with Gunnar Bucht?

SS: I don’t know if there are any typical works from that time, because I continued writing in all genres of music, from simple songs with piano up to orchestral pieces and full-scale opera. So I don’t have any typical pieces. I wrote an orchestral piece that was meant to be played by the orchestra of the school, and Bucht managed to have an agreement to make all the parts and scores and printing and so forth, and also with the professor in conducting, Jorma Panula, to direct this piece. But when it came time to begin the rehearsals, the students didn’t turn up. I don’t know if was a misunderstanding, bad planning… but it was never performed then. It was performed later.

TM: To follow up on what you were saying about moving from an intuitive approach to a more considered approach, would you say that your approach to composition is a narrative one, moving from the details to the structure, or an architectural one, moving from the large structure to filling in the details?

SS: Neither of them, really. I work with intuition. I don’t plan details. I have a goal, and I know where I am going, and I know what kind of stations I will pass, but the exact way of traveling, and who I meet — that is more from intuition, and almost improvisation sometimes.

It’s funny that you mention this about architecture, because one of my colleagues made a presentation about a concert of my music, and he made a comparison with architecture, saying that I am not one who makes a drawing or a sketch, something that you have to follow in every detail, but that I am an architect who uses one technique to build a pool, another for building a school, and another for building a theater, because you have to use different tools, you have to imagine different audiences, so that you have re-draw your drawings. I think that I work mostly from intuition and improvisation, but with a very clear goal.

TM: Another composer described a long piece as a long journey to a final vista, which has more of an effect because of the path you have to take to get there.

SS: Earlier I worked with texts — poetical texts, lyrics of different kinds, and abstract texts in non-existent languages, which helped me to make a structure. I also wrote four or five op eras, and equally many pieces for the stage. Now, in later years, I work more and more with chamber music, for special musicians, or for a special occasion, or for a special tour, or a special audience. That makes other demands, and gives other possibilities. The pieces are shorter, more concentrated. I wouldn’t say sketchy, but like short-hand, drawing — you throw out the idea rather quickly. I could write a piece in a couple of hours to be used the day after. In earlier times, I could sit for four or five months over a one-hour piece. It’s a different way of working today.

TM: Perhaps you might say something about your chamber music. You have a considerable amount of music for flute. Did you work with a particular flutist or flutists?

SS: I worked with the flutist Mats Möller, who did the first performances of many of my pieces. I wrote many of them for him or his ensembles. My wife, whom I met in 1995, is a flutist as well, so there are many pieces written for her to premiere. Her name is Kinga Práda, and she is originally from Transylvania. So I get big bites every day.

TM: Hence the title Vampire State Building.