January 31, 2012

Beverly Sills Artist Award Goes to Angela Meade

By Frank Cadenhead [Opera Today, 31 January 2012]

The seventh annual Beverly Sills Artist Award, carrying with it a $50,000 prize, was awarded to American soprano Angela Meade.

Angela Meade Wins Beverly Sills Artist Award

Muffy Greenough, Beverly Sill’s daughter, presented Meade the award on Monday at a ceremony at the Metropolitan Opera.

The honor is given to young artists who have already appeared in featured roles at the Met. She is singing Elvira in Verdi’s Ernani which opens at the Met on Thursday. She is also expected to appear in this role when this opera appears in theaters on February 25 as part of the series “Live at the Met.” Previous award winners include Nathan Gunn, Joyce DiDonato and John Relyea.

More information about the artist is available at: www.angelameade.com.

Frank Cadenhead

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Meade.png image_description= product=yes product_title=Angela Meade Wins Beverly Sills Artist Award product_by=By Frank Cadenhead product_id=Above: Angela MeadeRienzi, OONY

The orchestra sounds good, lovely rich string sounds that prefigure Tannhäuser, and coarse versions of Wagner’s endless modulation, continually reworking musical material to disguise his slight melodic gift. But it went on and on, brass choirs and brainless choruses, lovers rejoicing or denouncing, nobles sulking and plotting, and it was difficult to be sure which singer was playing which role; no synopsis was provided and, in Wagner’s libretto from a Bulwer Lytton novel about fourteenth-century Roman politics, only the three leads have any individuality.

Rienzi rates a single paragraph in Ernest Newman’s Wagner as Man and Artist. Newman loved Wagner, and his books are the best front-line tomes for background and analysis. He approved Wagner’s distinction between the “romantic operas” (up through Lohengrin) and the “music-dramas,” and when he said Wagner was the greatest opera composer who ever lived, he meant aside from the total-art-works in their higher realm. Yet even Newman (who has a ten-page warm spot for Das Liebesverbot) couldn’t come up with a kind word for Rienzi. “Almost offensive” and “a sheer failure of the imagination” are his dicta on the opera’s musical language. “It is astounding how few phrases there are in all these six hundred pages.” He grudgingly admits the “rampant horse-power vigor” of the overture (the only bit of the work we generally hear), then returns to its “vulgarity, its intolerable prolixity.”

I can’t disagree with this assessment, though Rienzi does offer the intriguing spectacle of youthful genius finding himself…and not quite getting there yet, just as Mozart does with Mitridate or La finta giardiniera. And, to be fair, Rienzi achieved just what its composer desired: A hit at its premiere, it remained popular for years, whereas Fliegende Hollander and Tristan took decades to enter the general repertory. From the chatter around me, I gathered that the house was full of last-minute attendees, lured by a spate of ten-dollar tickets, and that these newbies were happy with what they encountered, with the performance’s sheer busyness. Can opera lovers be so shallow that huge performing forces in colorful costumes and martial formation making a huge noise in a huge room, the power of mere spectacle, overwhelms refinement of taste? Well, you know the answer to that one.

Rienzi Vowing to Obtain Justice for the Death of his Young Brother by William Holman Hunt

Rienzi Vowing to Obtain Justice for the Death of his Young Brother by William Holman Hunt

The Met last gave Rienzi in 1890; 122 years do not justify any call for its revival. Opera Orchestra of New York has given it in concert four times now, at least two more than curiosity could merit, but Eve Queler loves operas that have lots of moving parts, brasses scattered around the room, choral groups marching up and down the aisles, a long organ solo, and Rienzi gives her all that. Wagnerians used to sneer at Rienzi as “the greatest Meyerbeer opera,” but that is because they do not know Meyerbeer’s tuneful, elegant, dramatically pointed scores. The only thing Meyerbeerian about Rienzi is its grotesque length. (Queler cut it significantly, of course: An uncut Rienzi could last five hours easy.) Rienzi’s repetitiveness, the thrill in exploiting its slight substance, no one would deplore more than Meyerbeer, unless it be the mature Richard Wagner. Effects without causes—that’s what we have here.

The 27-year-old composer, weary of being an underpaid, over-indebted opera conductor and critic, wanted to demonstrate he was ready for hardball with the big boys. You know: Spontini, Auber, Halévy… Too, he wanted to write an opera on imperial themes to set pre-unified Germany afire, and he wanted to set it in Italy because … well, because. But he hadn’t yet visited Italy. So the local color of his medieval Rome is very beer hall. A loud beer hall. A loud, smoky, Germanic beer hall. Hitler is said to have adored Rienzi, but too much need not be made of that: He also adored Die Meistersinger and The Merry Widow.

So the orchestra was okay on this occasion, and the choruses rather good, but what of the singers? Ian Storey, a well-known mediocre Tristan, was in appalling shape, not an unforced tone all day. As no announcement of ill health was made, one must assume he just wasn’t up to the stentorian title role, though he sounded very sick and Queler may simply not have had a replacement handy. (Who learns this role any more? Why bother?) Geraldine Chauvet in the musico (i.e., trouser) role of Adriano Colonna—the only character in the opera with a dash of personality—had a far happier day and the applause to go with it. She sang the Prayer that is the only vocal number ever excerpted from Rienzi, and though not entirely in charge of it, produced fine phrases in a yearning style and got through her Wagner turns, the composer’s favorite ornamental figure, with credit. Elisabete Matos, who made a thrilling Met debut last year in Fanciulla del West but is better known in Europe for dramatic roles, sang Rienzi’s sister and Adriano’s girlfriend, Irene, a one-(very high)-note idealistic personality whose soprano must cut through the orchestra like a gleaming bread knife. Matos had the sheen and was usually on the right pitches, and her final, suicidally heroic outburst implied that she’d sing one hell of a Senta if she got the chance. Among the lesser figures, baritone Shannon DeVine and soprano Emily Duncan-Brown distinguished themselves.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ColaDiRienzo.gif image_description=Statue of Cola Di Rienzo by Girolamo Masini, erected in 1877 near the Campidoglio product=yes product_title=Richard Wagner: Rienzi product_by=Irene: Elisabete Matos; Adriano: Geraldine Chauvet; Rienzi: Ian Storey; Baroncelli: Jonathan Winell; Cecco del Vecchio: Shannon DeVine; Messenger of Peace: Emily Duncan-Brown. New York Choral Society and Opera Orchestra of New York, conducted by Eve Queler. Avery Fisher Hall. Performance of January 29. product_id=Above: Statue of Cola Di Rienzo by Girolamo Masini, erected in 1877 near the CampidoglioCosì fan tutte, Royal Opera

Reviewing the February 2010 production, I remarked that Miller balances comic artificiality with more serious purpose; and, indeed, in a short programme note the director observes that “the awkward improbabilities of the plot [long the cause of the opera’s neglect and denigration] can be seen as a device that helps to make the opera more, rather than less, serious”.

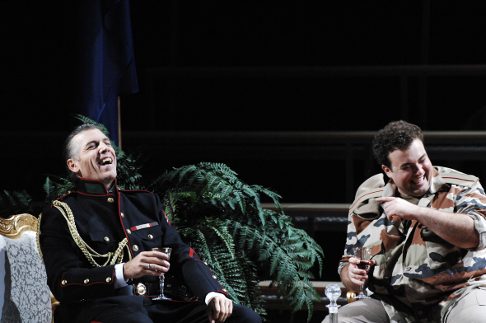

Despite this, there was much less gravity and momentousness on stage this time around, with the visual gags out-weighing the underlying moral solemnity. This was largely due to the self-indulgent, and thoroughly enjoyable, hamming of the two male leads — as alternately all-conquering UN blue berets and bandana-ed heavy metal aficionados; and to the comic artistry of Thomas Allen’s Don Alfonso, a suave and knowing master-of-ceremonies. Allen created this role in 1995, and having returned many times since he stepped effortlessly into the Machiavellian schemer’s Armani suit and shoes.

The quartet of lovers was accomplished if not stellar, with the men shining brightest. Returning to role of Ferrando, Charles Castronovo was in confident and engaging form; his tenor may lack tonal variety, but it is a flexible, pleasing voice, just right for the overly sentimental Ferrando. Lithe and limber of both voice and physique — he even punctuated a phrase or two with deftly executed press-ups! — Castronovo gave a consistent performance: his cavatina, ‘Tradito, schernito dal perfido cor’, was particularly affecting, the tender piano expertly controlled; and, in Act 2, ‘Ah, lo veggio’ attained even greater heights. His pairing with Nicolay Borchev’s Guglielmo was dramatically and musically effective; although Nicolay Borchev was perhaps overly robust and gruff at the opening, he soon settled down and his open sound aptly conveyed Guglielmo’s naivety and misplaced self-assurance.

The female pairing of Malin Byström, our indignant Fiordiligi, and Michèle Losier, a stroppy Dorabella, were less well matched vocally. Byström’s intonation was a little unsettled to begin, but once she got her vibrato under full control, she demonstrated more bite and focus. Her soprano has a limited palette and only one volume — fairly flinty and loud: this was apposite, however, for her melodramatic rendering of ‘Come scoglio’, which also showed off an impressively powerful lower register. Her phrasing might have benefited from greater melodic grace, but this was a striking representation of near-hysteria! Losier's voice is more opulent, and at first the girls’ sinuous interlocking thirds and sixths did not blend well. Dorabella was dramatically rather slight and superficial in Act 1 but Losier came into her own in Act 2; her duet with Guglielmo, ‘Il core vi dono’ was sweet and rich, and ‘È amore un ladroncello’ was full of character.

Thomas Allen as Don Alfonso, Michèle Losier as Dorabella, Malin Byström as Fiordiligi and Rosemary Joshua as Despina

Thomas Allen as Don Alfonso, Michèle Losier as Dorabella, Malin Byström as Fiordiligi and Rosemary Joshua as Despina

More satisfying, and exciting, was Rosemary Joshua’s Despina: striding forth in scarlet stilettos, she was not to be messed with. She patiently dismissed the spoilt hysterics of her employers, dealt deftly with Don Alfonso’s wandering hands, and relished the opportunity to don the Doctor’s gown and lap up the limelight as the be-masked doctor clad in green operating theatre garb, the cross-dressing role releasing Despina’s own exuberant theatricality. Agile and energised, both of her arias were expertly performed.

Allen himself was impeccable, his attention to musical and dramatic detail remarkable, especially in the recitatives. Indeed, having — intentionally or otherwise — taken an over-ambitious gulp of canapé, momentarily delaying his vocal entry in the opening scene, he had the audience eating out of his hand.

As Anne Ozorio put it, reviewing the September 2010 revival: “Sir Thomas Allen’s presence guaranteed success. Like Don Alfonso, he’s a grandee, elevated above the common run. The lovers strut and fret their hour upon the stage, but Don Alfonso’s seen it all before.” Suave, untroubled by events, assured of the outcome of his machinations, Allen’s dramatic urbanity was complemented by a relaxed, confident musical rendition of a role he must know backwards, upside down and inside out. His voice may not have quite the commanding presence of yesteryear, but experience and consummate ease goes a long to compensate for the odd ‘short cut’. Allen’s combination of musical nuance and dramatic credibility — as in the trio with Fiordiligi and Dorabella, ‘Soave sia il vento’, where he cynically and convincingly shares in their sorrow — confirmed him to be a true master of the theatre.

Charles Castronovo as Ferrando, Thomas Allen as Don Alfonso and Nikolay Borchev as Guglielmo

Charles Castronovo as Ferrando, Thomas Allen as Don Alfonso and Nikolay Borchev as Guglielmo

This production has been a good investment for the ROH; recalled at least every six months, perhaps the slightly distressed décor (white walls, white front drape, a sofa or two, a billow of cushions and an antique mirror affording our fickle foursome a narcissistic opportunity or two) is suitably cost-effective for this ‘age of austerity’. Modern and minimalist, elegant and economical, it may be; but, the Starbucks and mobile ’phone gags are wearing a little thin, and we’ve seen CNN cameramen rushing in to record unfolding events a few too many times now for this motif to retain its impact, or afford spontaneity to proceedings.

What was funny the first, or second, time around can, when repeated ad infinitum, become irritating: the snap-happy sisters are wedded to their camera phones, while Despina improvises a marriage contract on a laptop, and mobile ’phone ring-tones mingle with arpeggiated continuo chords. Admittedly, there has been some updating: Fiordiligi swiftly scrolls through her smartphone to find the perfect mugshot of Guglielmo, swiping the screen in perfect time to Mozart’s score.

But, there is a danger that such a plethora of visual gags will distract from the drama and from the emotional profundity of the music itself. Moreover, the staging lacks depth and variety of perspective: following the immediacies and energy of the opening trio, presented before the wafting white drape, the stage space beyond seems foreshortened and limiting. After all the busy phone-zapping, hair-coiffuring and Prozac-popping of the recitatives, with each aria or ensemble the principals invariably move to a stationary position at the front of a stage or settle gracefully and motionless on a pile of pillows. There is a surprising lack of direction in the substantial musical numbers, especially given the attention bestowed on the visual paraphernalia; this is particularly noticeable in the second act, where the drama becomes less frenetic and the sentiments more sincere. The chorus barely gets a look in, too often half-visible or practically ‘off-stage’.

Master Mozartian Colin Davis was in the pit, but while his reading has much elegance, the tempi were too slow; this did allow the twisting, sensuous woodwind melodies and timbres to shine, but the orchestra was repeatedly left behind by the principals, and it took until the finale to Act 1 for proceedings to reach a fittingly spirited romp.

Yet it mattered not, the evening was all about Allen, whose 40th year on the ROH stage the performance explicitly celebrated. Bouquets and a gigantic confection on wheels accompanied his curtain call. Allen threw several floral tributes back into the audience, declaring “I love this place”. I would not have been surprised to hear the answering cry, ‘We love you too”.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/COSI-FAN-TUTTE-2012JP_00907.gif image_description=Thomas Allen as Don Alfonso [Photo © ROH 2012 / Johan Persson] product=yes product_title=W. A. Mozart: Così fan tutte product_by=Ferrando: Charles Castronovo; Guglielmo: Nikolay Borchev; Don Alfonso: Thomas Allen; Fiordiligi: Malin Byström; Dorabella: Michèle Losier; Despina: Rosemary Joshua. Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Royal Opera House Chorus. Conductor: Colin Davis. Original Director: Jonathan Miller. Revival Director: Harry Fehr. Set designs: Jonathan Miller with Tim Blazdell, Andrew Jameson, Colin Maxwell, Catherine Smith and Anthony Waterman. Lighting design: Jonathan Miller and John Charlton. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Friday, 27 January 2012. product_id=Above: Thomas Allen as Don AlfonsoPhotos © ROH 2012 / Johan Persson

Le Roi et le Fermier

Opéra-comique began its long and significant existence as a sort of French opera buffa, with less grandeur in the musical requirements and spoken dialogue instead of sung recitative between numbers. Over the years this mixed genre evolved in many interesting ways, not always comical: Carmen began life as an opéra-comique.

Jeffrey Thompson as Lurewel

Jeffrey Thompson as Lurewel

Le Magnifique had pretty tunes but the presentation was undermined by two insurmountable problems: English plot summaries spoken between musical selections (instead of the original French dialogue) and a title character who never appeared on stage—horses don’t sing much in opera, even opéra-comique. Le Magnifique proved a great disappointment considering the company’s excellent track record without horses, but how do you solve the dialogue problem if the piece is not in the local language and you are unwilling to trust your singers as actors?

The company’s music director, Ryan Brown, evidently has a passion for the once-chic Monsigny, however, and this year (its 250th anniversary) he chose to give the composer’s 1762 opus, Le Roi et le Fermier. This piece has a simpler plot, drawn from an English play, and both title characters (king and farmer) appear on stage and even sing. Furthermore, Le Roi had legendary legs: A hit not only in Paris but in Vienna and St. Petersburg, Le Roi et le Fermier was revived in 1780 at the theater at the chateau of Versailles in a production designed for, and starring, Marie Antoinette, who sang the role of the put-upon Jenny, a virtuous farm girl besieged by a nasty milord. The queen’s brother-in-law, the future King Charles X, sang the not inappropriate role of a dim but valiant gamekeeper. The show was often given for a few years, before an audience as select as the cast to be sure, and—miracle of miracles!—the sets have survived, have been refurbished, and will be in use again later this winter—for Opera Lafayette’s French debut. So New York’s Rose Theater at Columbus Circle became, in effect, the site of the out-of-town try-out (without sets).

Dominique Labelle as Jenny, William Sharp as Richard and Thomas Michael Allen as Le Roi

Dominique Labelle as Jenny, William Sharp as Richard and Thomas Michael Allen as Le Roi

The plot is brief, basic, obvious, wry: The king (incognito) is lost in Sherwood Forest in a storm. A kindly farmer invites him to dinner. The king thus encounters honest subjects first hand, learning that the farmer’s fiancée’s dowry (a flock of sheep) has been stolen by the lustful milord. Meanwhile, the milord (his name is Lurewel, which must have been funnier in the original English), also lost in the woods, has been discovered by gamekeepers who think he’s a poacher. Brought to book, he recognizes the king, who then punishes him and ennobles the farmer—who rejects the title for the false tinsel it is. Kings reaching over the heads of the nobility to befriend ordinary folk was a theme very much in the air, though Louis XVI seems to have missed the point. Too bad; he’d have been good at it.

All this may seem artificial (is the average Western much better? The Good, the Bad and the Royal?), and Opera Lafayette rolled with it: Welcome, total artifice, so long as it is done with style. Didier Rousselet’s witty staging in projected sets (a wonderful dark forest) included silent movie bustle, mugging and mime, foolish costumes—it’s dark in that hut but would a king remain incognito in a jeweled silk waistcoat?—and a pair of intrusive but chic French narrators to speak the dialogue between the musical numbers, standing behind or beside the close-mouthed singers. One got used to this; it seemed part and parcel of the artifice.

The score is tuneful and rewardingly clever with very simple means: A duet for loutish baritone gamekeepers is followed by another for two foolish tenor fops, and then, since they are all lost in the same wood, have a quartet, devised by repeating the duets simultaneously! The three women in the cottage with their separate concerns (worried bride, puzzled mother, chattering child) become a lovely trio of contrasting vocal lines over a common melody in the orchestra. Simple ideas, these, but effective and, in the voices of an accomplished cast, delicious. Monsigny’s orchestration is lively and witty (a pre-Rossini storm, galloping horns for the king’s hunt, tinkling bells whenever money is mentioned), but his music is really not strong enough to carry the occasion on its own. The original run had singing actors not acting singers. Le Roi was probably known to—and inspired—Gluck, Mozart, Paisiello, even Beethoven and Rossini, but they each outdid their model. But it passed a charming evening, displaying another piece of the puzzle of how composers learned to use musical forms to dramatic effect, and how this blossomed into later, more elaborate opera. Marie Antoinette had her faults, but no one denies she had taste.

Scene from Le Roi et le Fermier

Scene from Le Roi et le Fermier

The Opera Lafayette cast sang French so well one was puzzled anew at their not being trusted to speak the dialogue as well. But many of these singers, who have impressed me on other occasions, in other halls, in far more difficult music (Handel, for example) seemed to lack bottoms to their voices in the Rose Theater. Does the hall cut off the lower notes (I sat in Row H) or were they not fully in command of their parts yet? Or did they underestimate the task required of them? Monsigny does not call for grand opera accomplishments and the ranges are smaller than Rameau or Gluck would demand, but miscalculation was in the air.

Dominique Labelle, in Marie Antoinette’s role of Jenny the shepherdess, was a case in point. Stunning as Handel’s Angelica in last summer’s Mostly Mozart Orlando, she had little use on this occasion for high notes or ornamentation, and her upper register was lovely—but low notes faded out. Her farmer, baritone William Sharp, was a suitable match for he suffered from the same defect: good phrasing, forthright mime, and a lower register that faded like woodland fog. They warmed up, but we did not warm to them.

The opera’s vocal bravado was given, as politics and tradition demanded, to its rankiest character, the King, tenor Thomas Michael Allen, obliged to sing of the glories of heroic battle because this is a fairy tale and the king must be brave as well as magnanimous. He did not have the serious grandeur, the glitter in alt that one might have hoped for in a monarch, and like the farmer hosts who insist that he sing for his supper, we were obliged to be indulgent.

Smaller roles were more happily filled. Yulia Van Doren, in stiff pigtails to symbolize her character’s age (fourteen), sang her little chanson deliciously (she’s kissed the king and been slapped by her mother) and made a convincing mime of childishness. Delores Ziegler held down the mother’s contralto lines well in the exquisite trio. The noble nitwits (who wears court wigs and satin in the woods?) were Jeffrey Thompson and Tony Boutté; the bluff and foolish deputies who arrest them (Charles X’s part) were Thomas Dolié and Jeffrey Newman, singing with great sturdiness. The Opera Lafayette orchestra was small but effective, making all Montigny’s delicate points with grace and Gallic lightness.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Le-Roi-8221.gif image_description=William Sharp as Richard and Thomas Dolié as Rustaut [Photo by Louis Forget courtesy of Opera Lafayette] product=yes product_title=Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny: Le Roi et le Fermier product_by=Jenny: Dominique Labelle; Betsy: Yulia Van Doren; La Mère: Delores Ziegler; Le Roi: Thomas Michael Allen; Lurewel: Jeffrey Thompson; Richard: William Sharp; Rustaut: Thomas Dolié; Charlot: David Newman. Opera Lafayette, conducted by Ryan Brown, at the Rose Theater. Performance of January 26. product_id=Above: William Sharp as Richard and Thomas Dolié as RustautPhotos by Louis Forget courtesy of Opera Lafayette

Vienna State Opera Keeps It’s Team

Meyer, born in the Alsace region of France, where German is a common second language, has worked in arts administration in France, including a period with the Opéra de Paris, and was the respected director of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris at the time he was given the job of Vienna’s “designated director” in June 2007. Only midway through his second season, his careful expansion of the opera’s repertory while giving attention to the conservative public has won him wide support.

Meyer’s hiring of Austrian-born Franz Welser-Möst, 51, as the General Music Director has also been a hit with audiences and critics. One of the top conductors of today, his music leadership has also been extended. Welser-Möst’s contract will now expire in 2018 but there is an option to renew until 2020. His current contract with the Cleveland Orchestra will draw to an end in 2018 also.

“Vienna has grown on me,” Meyer’s commented. “I have an excellent music director at my side, a wonderful team and I feel a lot of support from the audience. There is no better job in my profession than to lead the Vienna State Opera.”

Frank Cadenhead

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dominique-Meyer.gif image_description=Dominique Meyer product=yes product_title=Vienna State Opera Keeps It’s Team product_by=By Frank Cadenhead product_id=Above: Dominique MeyerVienna State Opera Keeps It’s Team

By Frank Cadenhead [Opera Today, 31 January 2012]

The recent announcement of the extension of the contract for Dominique Meyer, the General Director of the Vienna State Opera was a firm endorsement of his leadership by the Austrian government. Meyer, 57, the first French person to hold the office, will continue now through August 31, 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dominique-Meyer.gif image_description=Dominique Meyer product=yes product_title=Vienna State Opera Keeps It’s Team product_by=Frank Cadenhead product_id=Above: Dominique MeyerJanuary 27, 2012

Don Giovanni, Royal Opera

Thus, having kicked off in autumn with Puccini’s triptych, Il Trittico, we now have a triple dose of Mozart-Da Ponte, beginning with that delicious blend of the dissolute and the delectable, flavoured with a dash of the supernatural that, mimicking its slippery ‘hero’ himself, so often evades the directorial grasp: Don Giovanni.

Francesco Zambello’s staging, first seen in 2002 and revived several times since, is certainly full of fire, nowhere more so than in the final scene when flames literally threaten to lick the curtains and engulf the auditorium. But, although the ‘dissolute one’ is ultimately punished, this opera is about more than simply a ‘just’ meting out of hellfire and damnation; it is a ‘dramma giocoso’, and getting the right balance between menace and mischief, between horror and humour, is a tricky task.

Hibla Gerzmava as Donna Anna

Hibla Gerzmava as Donna Anna

Maria Bjørnson’s sets certainly tend towards the dark and dispiriting: a steely, curved wall suggests a suitably sepulchral edifice, festooned with crucifixes. Aloft perches a brooding, kitsch Madonna; it glowers judgmentally upon the degenerate goings-on, later prompting both a sacrilegious outburst from the frustrated sinner and a sentimental serenade from Don Ottavio. The ugly vertical construction revolves at the end of the first act to reveal a painted perspective of a grand banqueting hall, effectively transposing us from an abstract age scattered with assorted period allusions, to an unambiguous eighteenth-century Spain. By the beginning of the second act, the wall has crumbled into a pile of bricks and rubble.

This rather unappealing visual design is enlivened by the striking costumes whose deep, rich hues evoke the intense, contrasting palette of Goya, and integrate class signifiers and moral codes. The aristocrats sport royal blue and noble purple, while the peasants are dressed in simple (‘pure’?) white frocks; Don Giovanni is cloaked in crimson, as are his servants, excepting Leporello whose shabby, grey attire reflects the seediness and squalor of his existence.

Zambello’s ideas, though at times original and interesting, do not always add up to a complete whole; but if the show ‘works’, it is largely due to the musicality and muscularity of Gerald Finley as the eponymous philander, by turns imperious and charming, threatening and mesmerising. He is self-knowing but never self-pitying. Strikingly swathed in scarlet, from the first Finley is ruthless and dangerous, recklessly slaying the Commendatore, and later assailing Masetto with malice and spite. But, such viciousness is forgotten in a flash, as his voice enchants and allures. It is obvious why Zerlina submits so willingly, for ‘La ci darem’, like the subsequent Canzonetta, ‘Deh vieni alla finestra’, is breathtakingly sweet. Although we can see that the Don is oblivious to everything but his own satisfaction — sexual, gastronomic and material — Finley’s audacity, self-belief and independent spirit thrill us just as much as his vocal powers.

Matthew Polenzani as Don Ottavio, Hibla Gerzmava as Donna Anna, Marco Spotti as Commendatore

Matthew Polenzani as Don Ottavio, Hibla Gerzmava as Donna Anna, Marco Spotti as Commendatore

It is fitting that, following the ‘victors’ moralising fugato, it is the scorching silhouette of the wrong-doing reprobate bearing aloft a naked woman, anticipating continuing gratification, that is the image that brings down the final curtain; for it is Finley who has monopolised our attention and interest throughout. It is an image that neatly captures the irony that Mozart and Da Ponte surely intended, and the ambivalence that the score and libretto constantly declare.

Finley’s Leporello, Lorenzo Regazzo, could not match or, more appropriately, complement and counterpoise, his master’s dramatic or musical stature. In a disappointingly low-key performance, Regazzo’s fairly insubstantial bass offered neither comic capers nor buffo vengeance. There was much shoulder shrugging and miserable moping, but the catalogue aria was disappointingly dull — even Elvira looked bored, as she drifted about, disengaged and disinterested in the servant’s notebook flinging. However, Regazzo did perk up for the mock seduction of Elvira, enjoying his role-swapping adventures, his excited anticipation of the joys that his master’s costume endow, quickly turning to disillusionment when he gained not gratification but grief from the vengeful wronged.

Gerald Finley As Don Giovanni, Lorenzo Regazzo As Leporello

Gerald Finley As Don Giovanni, Lorenzo Regazzo As Leporello

But, underpowered vocally and dramatically, Regazzo got ‘lost’ in the chaos that concludes Don Giovanni’s party and in the final banquet scene, in which Leporello’s heartlfelt terror should serve to emphasise his master’s insouciant self-assurance, he went unnoticed.

The big surprise of the evening was Matthew Polenzani ’s Don Ottavio; this effete aristo was a far cry from the ineffectual posturer and grumbler of far too many productions. Indeed, Polenzani won the loudest applause of the night, for his pianissimo da capo of ‘Dalla sua pace’ which was truly refined.

There were strong performances too from Adam Plachetka (Masetto), a dark voiced bass-baritone of stature, and Marco Spotti, who was a commanding Commendatore.

The female leads were all making house or role debuts. Wearing a Havisham-esque gown, Katarina Karnéus was an overly melodramatic Elvira; with little help from the director, her perfectly plausible anger lacked focus, and often lapsed into deranged ranting and raving. Moreover, why is she borne in in a sedan chair? She is surely savagely incensed, rather than self-composed and sedate? Despite this, Karnéus did convincingly convey Elvira’s unpredictable mood swings: she has gloss and clarity at the top, but lacks weight and richness in lower range. And she didn’t quite have sufficient stamina, tiring in ‘Mi tradi’.

As Donna Anna, Hibla Gerzmava’s hard-edged tone was a good match for her ‘hard-to-get’ stance with Ottavio, but won her character little sympathy. Irini Kyriakidou was a mature, knowing Zerlina but, while mostly secure, she lacked variety of tone.

Zambello’s banquet scene is a mixture of the banal and the blood-curdling. There is no statue — although, puzzlingly, the chorus stand stock-still, like frozen figurines, when Don Giovanni invites his ghostly guest to dinner. Instead of an imposing effigy we have an enormous swinging, pointing finger - the hand of God, we suppose, or else that of the Commendatore himself, mocking the beguiling invitation of the Don’s seductive serenade.

Scene from Don Giovanni

Scene from Don Giovanni

While there were dazzling pyrotechnics on stage, there was disappointingly little fervour in the pit, despite the breakneck pace of the overture which promised so much. Constantinos Carydis, conducting from memory, let the momentum droop and drag, at times unsettling his soloists (even Finley, who surprisingly anticipated the start of ‘La ci darem’) and wrong-footing his chorus, who tripped and stumbled through the Act 1 finale. Carydis clearly possesses a detailed knowledge of the score but there was simply not enough attention to the overall ensemble, which was sacrificed for momentary nuances. The recitatives were enlivened by some witty continuo playing from Mark Packwood, and the ‘Girl-bands’ and other musicians at the Don’s wedding feast — playing from memory — provided impressive entertainment.

Ultimately, whatever the flaws of conception, design and performance, Finley’s masterful performance ensured a satisfying evening was had.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DON_GIOVANNI_10200_0165.png image_description=Gerald Finley as Don Giovanni and Katarina Karnéus as Donna Elvira [Photo by Mike Hoban courtesy of the Royal Opera House] product=yes product_title=Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Don Giovanni product_by=Don Giovanni: Gerald Finley; Leporello: Lorenzo Regazzo; Donna Anna: Hibla Gerzmava; Donna Elvira: Katarina Karnéus; Don Ottavio: Matthew Polenzani; Zerlina: Irini Kyriakidou; Masetto: Adam Plachetka; Commendatore: Marco Spotti. Royal Opera Chorus. Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Conductor: Constantinos Carydis. Director: Francesca Zambello. Designs: Maria Bjørnson. Lighting Design: Paul Pyant. Fight Director: William Hobbs. Movement: Stephen Mear. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Saturday, 21 January 2012. product_id=Above: Gerald Finley as Don Giovanni and Katarina Karnéus as Donna ElviraPhotos by Mike Hoban courtesy of the Royal Opera House

Basel Chamber Orchestra, Wigmore Hall

Directed by their energetic leader, Yuki Kasai, and joined by tenor Mark Padmore and horn player Olivier Darbellay, they offered a thought-provoking performance at the Wigmore Hall which was musically and intellectually satisfying.

The contemporary Swiss composer Lukas Langlotz was born in Basel, and stStudierte an der dortigen Musikhochschule Klavier (bei Jean-Jacques Dünki), Dirigieren (bei Wilfried Boettcher und Manfred Honeck) und Komposition (bei Rudolf Keludied piano, conducting and composition at the Conservatory of his home town, before further studies in Paris and Lucerne. His arrangements of three well-known songs by Henry Purcell, which opened the concert, presented very interesting instrumental combinations and colours - the strings of the Basel Chamber Orchestra extending the original lute accompaniment into a shimmering array of tonal and textural blends - allied to tense, explosive rhythms. Textures were often lucid and light, as the orchestra proposed independent musical ideas beneath and between the vocal declamations.

But, while intriguing, these arrangements were over-complicated and at times intrusive, disturbing the measured declamation of the vocal line and unbalancing the relationship between voice and accompaniment. For example, the textural and rhythmic complexities of the accompanying ensemble rocked the structural foundations provided by the five-bar ground bass in the ‘Evening Hymn’, obscuring the subtlety of the flexible dialogue between the vocal line and the repeating ground the asymmetries of which contribute so much to the expressive freedom and power of the song. ‘Let the night perish’ is perhaps more suited to exaggeratedly dramatic presentation; here Padmore ranged affectingly from despair - “May the dark shades of an eternal night/ Exclude the least kind beam of dawning light” - to devotion, concluding with a poignant prayer that all, from the richest monarch to the poorest slave may “Rest undisturb’d and no distinction have/ Within the silent chambers of the grave”. Padmore’s strong tenor was employed flexibly and with thoughtfully applied dynamic range. Overall, though, the balance between voice and chamber orchestra was not always ideal; there was undeniably much intensity, but little poignancy, joy or peace.

Britten’s Serenade for tenor, horn and strings is inevitably still haunted by the shadows of its first performers, Peter Pears and Dennis Brain, who premiered the work in this very Hall in 1943. Padmore and Darbellay gave a reading that was personal and individual, while remaining in tune with Britten’s vocal aesthetic which promotes the centrality of the text above mere ‘beautiful singing’. Indeed, Padmore’s own website avowals that “One of the great things I enjoy about singing is exploring texts”. That’s not to suggest that his singing is not beautiful … if occasionally a few of his textual emphases were a little mannered, Padmore’s tenor was always richly expressive, his diction clear without being overly emphatic or distracting. He dispatched the virtuosic demands of Britten’s vocal writing with ease, creating an array of wonderful vocal vistas to depict the changing poetic worlds. The sincerity and poise of the opening ‘Pastoral’, with the horn sensitively echoing and interweaving with the voice, evolved to a heightened dramatic tension in Tennyson’s ‘The splendour falls on castle walls’, and was transformed into an eerie darkness in Blake’s ‘O Rose, thou are sick!’, Darbellay perfectly matching the modulations of vocal tone. Daring and vibrant pizzicati enhanced the mood of apprehension and strain in the Dirge; indeed, throughout the evening the violins’ intonation was superb, and the players introduced much freshness to these familiar songs, if at times their timbre was somewhat austere, even abrasive. The final song, a sensuous setting of Keats’ sonnet to that ‘soft embalmer of the still midnight’, concluded the cycle in rapt intensity.

It’s only a small quibble - and one which may seem uncharitable given the technical finesse of Darbellay’s natural harmonics - but perhaps Darbellay was a fraction too authoritative in the horn introduction, which should surely sound mysterious and nocturnal, shrouded with a touch of vulnerability? The concluding off-stage reprise was, however, deeply moving: tender and poignant.

Darbellay returned after the interval to perform Mozart's Second Horn Concerto, once again producing a rich array of colours, most notably in the redolent lyricism of the opening movement where the soloist was accompanied by rhythmically buoyant, carefully phrased and feisty playing by the BCO. The final work of the evening, Haydn’s rarely performed Symphony No.52, was a little more untidy, although similarly charged with energy and exuberance. The Andante offered respite and relaxation after the stylish exuberance of the Sturm und Drang first movement, the players appreciating the density of the organically unfolding material and Haydn’s harmonic complexities. This was impressively committed playing.

Claire Seymour

Programme:

Purcell, arr. Lukas Langlotz; Thou wakeful shepherd (A Morning Hymn); Now that the sun hath veiled its light (An Evening Hymn); Let the night perish (Job’s Curse).

Britten: Serenade Op.31 for tenor, horn and strings.

Mozart: Horn Concerto No. 2 in Eb K.417.

Haydn: Symphony No.52 in C minor.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Yuki_Kasai.png image_description=Yuki Kasai product=yes product_title=Basel Chamber Orchestra, Wigmore Hall product_by=Basel Chamber Orchestra. Yuki Kasai, violin. Mark Padmore, tenor; Olivier Darbellay, horn. Wigmore Hall, London, Wednesday 18th January 2012. product_id=Above: Yuki KasaiLa Bohème in Toulon, Marseille and Genoa

Well, why not? Why not make La Bohème about 1968! 1968 was a long time ago, dim in memory but now that you mention it an exciting time to recall — the vehement anti-Vietnam war protests in the U.S. were small in comparison to Mai 1968, huge protests in Paris and around France against authority (any and all), a premise wildly cheered by American and Italian university students eager for any and all revolution, all this general excitement notably prompted by the politically pointed 1968 Prague Spring.

Maybe May 1968 is a mantle that La Bohème does not wear very well. But never mind, it was fun to revisit those exciting times even if the 2003 Nice Opera production by Daniel Benoin revived just now in Toulon was filled with much imagery that was maybe recognizable only by the French, and by now those French of a certain age (this seems to have been the case based on overhearing intermission conversations). It did leave us Berkeley-ites of a certain age mostly in the dark.

A bit of post-performance research into Mai 1968 explained that the rubber face-masked, caricatured Maoists who marched in at the end of Act II were deriding the French communists who joined the rightwing Gaullists to condemn the strikes. Riot police were everywhere in Mai 1968 (DeGualle had fled to Germany) thus they prefaced the third act by climbing onto the stage to be in place before the curtain rose onto a mesh fence with a gate that guarded some sort of internment compound and then inexplicably did not.

Mr. Benoin, director of the esteemed Théâtre National de Nice since 2002, is not a musical opera director, if he were musical he would know that you better not mess around with La Bohème at all. He would know that posters announcing the appearance of Country Joe and the Fish at the Café Momus would disqualify Puccini’s orchestra, that Musetta, a determined, militant revolutionary, could not croon her waltz into a microphone to a mute jazz trio accompaniment. He would know that if a corps de ballet did happen by the Café Momus it would not attempt to jive dance to Puccini’s trumpet fanfares.

But make no mistake, Mr. Benoin is a savvy director (making one curious if a little nervous about the Madame Butterfly he staged in Salerno [Italy] in 2007). He used his Act III wire mesh fence to sublime effect, separating his sets of lovers while allowing them to touch. His Act IV conceit was to clothe his entire cast in pure white, Rodolfo draping the windows with white cloth at the moment Mimi expired. All this packed a wallop.

If Daniel Benoin indulged himself in seemingly arbitrary forays into high theatrical style Toulon Opera music director Giuliano Carella indulged Puccini in some very powerful verismo that exactly magnified the opera’s emotive intent to huge proportion, real and pure embodiment of the verismo ideal of oversized sentiment. This an accomplishment rarely achieved on any operatic stage. Well, once we got to Act III that is. Acts I and II were rocky, evoking terrors that are usually dealt with at the dress rehearsal. And the maestro simply could not drag the Toulon chorus into a festive melée at the Café Momus.

Finally La Bohème rests on the charm and voice of its bohemians, and Toulon Opera did not let us down. The Bohème herself was Italian soubrette Nuccia Focile whose mannered Italian endowed Mimi with more personality than we may have wanted but whose voice rose to easy highs to insinuate a younger and simpler idea of this heroine. Sympathetic Polish tenor Arnold Rutkowski, easily the audience favorite, drew his musical lines with more than usual ease suggesting that Onegin’s Lenski is his innate character. Georgian born French soprano Anna Kasyan brought good, tough character to this unusual Musetta though she only sometimes seemed to have the requisite vocal heft. Italian baritone Devid Cecconi was a gruff, lovable, bumbling Marcello aided by countrymen Massimiliano Gagliardo and Roberto Tagliavini as the charming and vocally adept Schaunard and Colline.

Trailer for Toulon production of La Bohème

Well, why not translocate La Bohème onto the rooftops of Paris, maybe like a movie musical (Moulin Rouge for example)? These rooftops rarely have people on them for good reason (they are steep) so the trick just now in Marseille was finding a few flat places where bohemians could frolic and die.

Rooftops are just that so there was no way to sketch an artists’ garret, a café or an entrance to the city, after all these places are easily imagined. Maybe this lone rooftop location was a bow to the new austerity that has made opera companies worldwide feel as penniless as Puccini’s bohemians.

La Bohème is indestructible, or nearly. The holiday season Bohème at Marseille Opera toyed with that distinction. This Christmas Eve bonbon (well, the first two acts) might have survived the rooftop concept but it could not survive the attempt to turn Puccini’s thrusting emotions into the measured, percolated, precious movements of spirit that mark a Britten or Janacek opera. Like a driver willfully blocking the flow of traffic by driving too slowly to prove how careful he is, Irish conductor Mark Shanahan thwarted the very essence of verismo by rendering it into slow, almost frozen musical motion. The cathartic moment of Puccini’s tearjerker in Marseille finally was not a tear or two, it was pure and simple road rage at the conductor.

Were it not victim of the conducting this La Bohème probably would have succumbed at the moment Musetta’s waltz became a 1950’s movie musical production number, those Parisian rooftops disguised very symmetrical platforming that allowed a garishly costumed Musetta, let us say clownishly, to top a pyramid of snazzy Café Momus waiters executing some snappy choreography. Well, Café Momus was already a crazed showbiz, dayglo colored adult playground so why not.

It would be unfair to delve too deeply into the individual performances as there was obvious dissension between pit and stage, and not just between the singers and the conductor, also between stage management and conductor — changes in the lighting seldom occurred at the appropriate musical moment.

Promotional photo of Marseille production of La Bohème

Promotional photo of Marseille production of La Bohème

Suffice to say that French soprano Nathalie Manfrino was a vocally and physically attractive Mimi, though her ample sound was mismatched to Ricardo Bernal as the young, handsome Rodolfo. This Mexican tenor’s appropriately Italianate delivery was hampered by a voice more suited to the light lyric roles. Marcello, Schaunard and Colline were undertaken by Marc Barrard, Igor Gnidii and Nicolas Courjal respectively. All are accomplished in their roles though none found the youthful charisma of their characters as had the Mimi and Rodolfo.

The staging concept credited to Jean-Louis Pichon seems to have been to transform Puccini’s sad little tale into a slick musical with one nifty crowd scene, leaving the well known tunes elsewhere to fend for themselves as well they might and usually do. Marseille’s remarkable opera house, unequaled anywhere for its direct stage-audience rapport did respond from time to time to the obtuse staging with some enjoyable stage pictures.

Well why not? Why not place Puccini’s sad, gritty little story in an enchanted storybook world where fantastically dressed bohemians named Mimi, Rodolfo, Marcello, Schaunard and Colline have identically fantastically dressed child counterparts aged 5 to 9 who mirror their every move.

There was no message in Genoa just now, like innocence is transitory if not illusionary — “just wait until you grow up, kids, life gets complicated.” Instead it was simply the bi-polar Bohème pathology gone extreme. The first two acts of the opera are indeed childish play, as are the antics of the fourth act, and you know the rest of the story.

The juxtaposition of storybook and real seemed ridiculous but once you thought about it, well, thought about it quite a lot, you could make it make some sense. It was a justifiably abstracted bi-polar world that incorporated Puccini’s verismo, if uncomfortably, by separating the visual and sonic worlds. The musical was what is real, even tangible (like great verismo really is), and the visual became a metaphysical world that shadows and colors the real, like music ordinarily does (yes, this conclusion took some thinking).

So we were very much on edge, and maybe heard this great masterpiece with new ears, as we were seeing it with new eyes. There were other advantages that we will get to.

Scene from Genoa production of La Bohème [Photo by J. Morando]

Scene from Genoa production of La Bohème [Photo by J. Morando]

Teatro Carlo Felice invited Genoa born and culturally nurtured artist Francesco Musante to create this new production. Over his long career Mr. Musante has exploited op art and Viennese Succession influences, he has worked in water color, lithograph and particularly illustration. A specific reference in his oeuvre to this telling of La Bohème might be his comic book rendition of Lewis Carrol’s Alice in Wonderland (1980). Mr. Musante is not widely known outside Italy.

The Musante abbozzi, or renderings of the scenes displayed in the foyer of the opera house succinctly expounded the artist’s specific vision of La Bohème — a bright and noisy world animated by children. Act II was in fact an illustrated music box merry-go-round wound up by the children on the stage at the end of Act I.

On the Carlo Felice stage Mr. Musante’s sketches were made live by Italian actor Augusto Fornari who presumably was in cahoots with the artist. This obviously able stage director was hampered by the absence of professional child actors, here the extensive mimicry was supplied by members of the Carlo Felice’s Children’s Chorus (“coro di voci bianchi”). But what a chorus this was! The first in living memory to carry out hyper visual antics in perfect [!] synchronization with the Puccini’s musical antics — among them the entry of a 12 member (maybe more) marching band that capped the Momus act with utter visual and musical delirium.

Unaided by any visual realism whatsoever, conductor Marco Guidarini managed only a restrained verismo that fully supported Puccini’s needs but mostly missed finding a synergy with the stage. If this Bohème’s visual world was exuberant and extravagant, Mo. Guidarini’s Puccinian thrust was careful and by-the-book when it could have been pushed to and even beyond verismo extremes.

Musante’s stylized visual language obliterated the need for singers to look or be bohemians, thus they came in all shapes, ages and sizes but to a man on January 5 they had solid Italian schooling and gave big vocal performances with big mannerisms that might be considered tasteless in more restrained musical cultures. Three casts people its eleven performances over a two month period (into February). On January 5 Massimiliano Pisapia was the Rodolfo, though were it not for his musical postures he might have been singing Siegfried. Amarilli Nizza is an accomplished Tosca and Aida on big stages (Verona, Vienna) so she was hardly a retiring Mimi. Hers was a fully successful, vocally and musically splendid performance. Of special interest as well was the Musetta of Alida Berti whose vocal and presence actually matched the exuberance and innocence of the production, as did the remarkably vivid, full voiced Alcindoro of Fabrizio Beggi.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Toulon_Boheme.gif image_description=Scene from Toulon production of La Bohème product=yes product_title=Giacomo Puccini: La Bohème product_by=Toulon Production. Mimi: Nuccia Focile; Rodolfo: Arnold Rutkowski; Musetta: Anna Kasyan; Marcello: Devid Ceconi; Schaunard: Massimiliano Gagliardo; Colline: Roberto Tagliavini; Benoit & Alcindoro: Guy Flechter; Parpignol: Jean-Marie Bourdiol. Chorus and Orchestra of Opéra Toulon Provence Méditerranée. Conductor: Giuliano Carella. Mise en scéne: Daniel Benoin. Sets and costumes: Jean-Pierre Laporte and Daniel Benoin. Lighting: Daniel Benoin. (December 29, 2011)Marseille Production. Mimi: Nathalie Manfrino; Musetta: Gabrielle Philiponet; Rodolfo: Ricardo Bernal; Marcello: Marck Barrard; Colline: Nicolas Courjal; Schaunard: Igor Gnidii; Benoit: François Castel; Alcindoro: Antoine Normand. Chorus and Orchestra of Opéra de Marseille. Conductor: Mark Shanahan. Mise en scéne: Jean-Louis Pichon. Scenery: Alexandre Heyraud. Costumes: Frédéric Pineau. Lighting: Michel Theuil. (January 3, 2012)

Genoa Production. Mimi: Amarilli Nizza; Musetta: Alida Berti; Rodolfo: Massimiliano Pisapia; Marcello: Roberto Sèrvile; Schaunard: Dario Giogelé; Colline Christian Faravelli; Parpignol: Pasquale Graziano; Benoit: Davide Mura; Alcindoro: Fabrizio. Chorus and Orchestra of Teatro Carlo Felice. Conductor: Marco Guidarini. Scene and Costume Design: Francesco Musante. Stage direction: Augusto Fornari. Lighting: Luciano Novelli. (January 5, 2012) product_id=Above: Scene from Toulon production of La Bohème

January 25, 2012

The Enchanted Island, Metropolitan Opera

Another, Anna Bolena, was more than simply a new production to mark opening night. It was also a new addition to the company’s repertoire. Still another, The Enchanted Island, was a world premiere. In this final instance, the composer who was lucky enough to land such a high profile engagement was none other than…George Frideric Handel?

Danielle de Niese as Ariel

Danielle de Niese as Ariel

If this seems perplexing, don’t worry, it is. What’s even more confusing is, he is not the only composer to create this new work. The others, Antonio Vivaldi and Jean-Philippe Rameau, are just as old. The question then becomes: how can an opera be new if it utilizes music that is over two hundred years old? The answer is not as difficult as it would appear. The Enchanted Island, the brainchild of famed conductor and Baroque interpreter William Christie, with an English language libretto by Jeremy Sams, is meant to be a modern take on a Baroque genre known as pasticcio, in which multiple arias from one or more composers would be combined with occasional changes in text to create an entirely new plotline.

The idea of a modern pasticcio fits well into the scheme of the modern Baroque revival, which began in the latter half of the 20th century. However, despite the similarities between Baroque and Bel Canto opera, which was revived around World War II, Baroque works pose a greater challenge to modern audiences.

Lisette Oropesa as Miranda

Lisette Oropesa as Miranda

This is because all aspects of Baroque opera performance practice are closely tied to the promotion of the absolutist regimes of the 17th century. In our modern era, when audiences are so far removed from these institutions, the challenge becomes making these works speak to people with the same immediacy they did centuries ago.

In this light, this opera, which combines elements of The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream into a comedy of errors and mistaken affections, was a rousing success. The work manages to flawlessly combine the diverse aspects of Baroque opera, such as the da capo aria, the use of ballet, innovative stage craft, as well as the distinction between recitative, arioso and aria seamlessly. Its principal roles, sung by such lauded Baroque interpreters as countertenor David Daniels (Prospero), soprano Danielle De Niese (Ariel), and mezzo soprano Joyce DiDonato (Sycorax), made an excellent case for the emotive power of Baroque music, especially its ornamentation, while at the same time updating the somewhat stilted figures of tragic nobility which populate Opera Seria.

In contrast to a work like Handel’s Giulio Cesare, in which the just nobles, Cesare and Cleopatra, are pitted against the wicked nobles, here symbolized by Ptolemeo, the nobility of The Enchanted Island was neither totally sympathetic nor totally antipathetic. Instead, each aria focused on the humanity of the emotions each character was feeling. In this light, Joyce DiDonato stole the show. Her opening aria, “Maybe Soon, Maybe Now,” showcased her ability to draw the emotive colors of Baroque ornamentation, which included growls.

Joyce DiDonato as Sycorax, Placido Domingo as Neptune, and David Daniels as Prospero

Joyce DiDonato as Sycorax, Placido Domingo as Neptune, and David Daniels as Prospero

There were times when Danielle de Niese used her coloratura to explosive effect. In much the same way, David Daniels showed how improvised vocal technique could be used for emotional display. His legato showed vulnerability while his ornaments illustrated a fierce display of anger. Other standouts include Layla Claire as Helena and Elizabeth DeShong as Hermia; their voices blended excellently in their duet where they complain of their lovers’ rejection. Lisette Oropesa was a rather vulnerable Miranda. She gave an excellent turn in her arioso. Luca Pisaroni was comical yet sympathetic as Caliban. His role as Caliban allowed him to express the depth he is capable of. Countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo was brilliant in the brief but crucial role of Ferdinand. Lastly, Placido Domingo, singing on his 71st birthday, was thrilling as Neptune. It is good to see that despite his age, his skill as a consummate performer has not diminished. However, his diction suffered at the expense of the fast runs of his music. In the end, that did not reduce the overall effect of his performance.

The production, directed by Phelim McDermott, combined elements of ancient Baroque productions with modern technology. The audience was able to see the full extent of the Metropolitan Opera’s resources, both in costuming as well as in technology. This allows modern audiences to experience the opera as someone would have back in Baroque times.

Layla Claire as Helena and Luca Pisaroni as Caliban

Layla Claire as Helena and Luca Pisaroni as Caliban

I have only two criticisms. On occasion, the music didn’t fit the text. Naturally, this genre of opera is predicated on the da capo aria, with its contrasting A and B sections as symbolic of the Aristotelian view of rhetoric that was popular at the time. However, most often, in the music of Sycorax, as well as the early music of Ariel, the text seemed to depict the opposite of what the music was communicating. In the case of Sycorax, her text would be asking for pity when the music was bloodthirsty for revenge. Also, the opera is long, especially the first act. Prospero’s aria, which closes Act I, in which he expresses dismay at all the confusion he has caused, could just as easily have been moved to the beginning of Act II. This would have allowed Act I to end with the fanfare at the end of Neptune’s scene: a much stronger point for a finale.

When everything is taken into consideration, The Enchanted Island is indeed a new opera. Despite the fact that none of the music is original, it successfully recasts all the facets of the genre in a new light, which concentrates less on politics and more on artistic expression. If the multitude of young children at the performance was any indication, this opera met its goals with great success. As long as it can draw new audiences and demonstrate the staying power of its music, the Baroque revival is on track.

Greg Moomjy

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENCHANTED-ISLAND-Daniels-34.gif image_description=David Daniels as Prospero [Photo by Ken Howard courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera] product=yes product_title=The Enchanted Island (Devised and Written by Jeremy Sams) product_by=Click here for production information. product_id=Above: David Daniels as ProsperoPhotos by Ken Howard courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera

Haydn’s The Seasons at Barbican Hall

McCreech and his performers painted a collection of charming, detailed pictures of rural life, belying Hadyn’s own professed distaste for the text’s invitations to ‘word-painting’. The composer famously described what he considered the overtly mimetic sections depicting cocks growing, frogs croaking and so on as “Frenchified trash”, but here such sonic images brought much delight and were perfectly balanced with the more abstract reflections contained within Baron Gottfried van Swieten’s libretto.

After their success with The Creation (for which van Swieten had adapted and arranged episodes from Genesis and John Milton’s epic, Paradise Lost), the impetus for a new work seem to have come largely from van Swieten, who eagerly proposed another possible English language source to Haydn - John Thomson’s poem, ‘The Seasons’. The original comprises more than 4300 lines of poetry of a philosophical nature; Van Swieten selected, revised, re-ordered and translated, focus on the descriptive passages and producing a rather banal libretto, but one which did accord with the spirit of Enlightenment optimism, and which offered the composer much opportunity for illustrative detail.

However, The Seasons did not come easily to the once prolific Haydn. He reportedly found the text irritatingly simplistic; but, perhaps more significantly, the aging composer complained of weariness, lamenting his waning imaginative resources and “feeble memory and the unstrung state of my nerves so completely crush me to earth, that I fall into the most melancholy condition”.

The Seasons received its first performance in a private venue at the Schwarzenberg Palace in Vienna in April 1801. A month later it was rapturously received by the Viennese public. However, it was less celebrated in France and England, where Haydn had previously has such success and renown, and H. C. Robbins Landon has observed that this lack of interest may have heralded the decline and fall to the near oblivion that Haydn’s music would suffer in the nineteenth century.

Naturally, The Seasons falls into four parts. To begin, the “softest zephyrs, warm and mild” herald the rebirth of the dormant natural world, following a startling, large-scale orchestral introduction where explosive timpani strikes and syncopated rhythms evoke the shuddering passage from winter to spring. There are in fact instrumental ‘prefaces’ to each of the seasonal quarters; and the large Gabrieli Consort, with a rich brass ensemble of four horns, two trumpets, three trombones and full strings and woodwind, created varied, captivating soundscapes. Sweet flutes evoked spring’s mild airs during the opening accompanied recitative; gorgeously opulent horns rang triumphantly, first in Summer as the wakeful herdsman gathered up his cheerful flock, and later, joined by trombones, in a blaze of colour and energy in Autumn’s closing chorus, as “sound of the chase in the forests resound”. String playing was animated and nimble; accurate intonation characterised the unison chromaticisms which evoke the grey dawn indicating the beginning of Summer, while a glistening tremolo haze signalled that season’s fiercely blazing sun which “pours through clear and cloudless skies/A torrent of fire on the meadows below”. Textures were unfailingly crisp and clear, the four-note motif upon which Winter’s bleak Adagio introduction is founded wonderfully suggesting the wisps of swirling, freezing fog whipped up by the bracing wind.

The Seasons features three principal characters—Simon, a farmer (bass/baritone); Hanne, his daughter (soprano); and Lukas, a country lad (tenor) — who ruminate on aspects of peasant life, narrating personal anecdotes and reflecting on more abstract ideas.

As Simon, Christopher Purves’ full, round baritone carried the text powerfully to the furthest reaches of the Barbican Hall, every word of recitative crisply articulated and nuanced. In Autumn, the vigour and vitality of his singing inspired the chorus in their hymn to the joys of ‘industry’ (‘Thus nature rewards our toil!’). His aria, ‘See there on yonder open field’, was similarly enlivened and theatrical, as McCreesh judged the accelerandi and dramatic pauses that depict the dog as he “races in pursuit of his prey, then stops at once, and freezes, motionless as stone”, and the “terror swift” of the bird who takes wing “to escape th’approaching foe”, to perfection. In Winter, Purves effectively brought about a surprising change of mood in ‘Consider then, misguided man, the picture of thy life unfolds’, as the vivid immediacy of “icy blasts of piercing cold” are replaced by more abstract reflections upon the transitory nature of man’s life, leading to the final double chorus of praise to God for his gift of nature and its power of renewal.

Lukas’ cavatina, ‘Exhausted nature, faint ing sinks’, depicting the dazzling, debilitating heat of the midday summer sun, is one of the most beautiful numbers in the oratorio, and Allan Clayton’s serene, controlled pianissimo, supported by subdued low strings and gentle falling figures for flute and oboe, was supremely affecting. Clayton was unfailing alert to textual detail: at the start of Summer, the line “In darkness shrouded, steals the dawn, in pearly mantle” wonderfully expressed the intense anticipation and hope as “the weary night retires”. Lukas' Winter aria, ‘The wand’rer stands perplexed’, describing a traveller who falters and loses his way in the drifting snow, was especially poignant. Elsewhere Clayton’s fresh tone emphasised the works frequent affinity with folksong and Singspiel, as in the song of joy —a charming Andante dialogue between Lukas and Hanne — concluding Spring, which creates a mood of bucolic simplicity and delight recalling the unaffected world of Papageno and Papagena.

Christiane Karg’s Hanne was without affectation; a modest peasant girl, her well-centred soprano entertained the women spinning by the winter fire in an enchanting strophic Lied, as bubbling viola motifs depicted the “whirring” and “purring” of the spiralling wheel. Karg brought passion to her tone when joining with Lukas to relish the “bliss of love’s sweet rapture”; and she was not afraid to create a shriller sound to convey the “fear and trembling” of the pretty maid who fears the predatory nobleman but, as in all good folktales, uses her wile and wits to get the upper hand.

The principals are joined by a chorus of country folk, who provide glorious general hymns of praise at climactic moments, and form a dramatic cast of peasants, hunters, revellers and spinners. The Gabrieli Consort sang lustily and lustrously, relishing the more operatic moments of the score. The earth-shattering summer storm, and the exuberant hunting scene depicting the thrill of the chase and the riotous inebriation with which its success is celebrated, were impressively arresting. The Handelian fugues which conclude many of the seasonal sections were dynamic and uplifting.

All credit to McCreesh for inspiring his players and singers to perform with such startling energy and vitality. But, the moods were varied: equally striking was the clearing of the summer storm and the tolling of evening bells calling man and nature to rest. Despite the apparent increasing frailty and exhaustion of its composer, in this invigorating performance of The Seasons, there was evidence only of youthful vigour and joyful spontaneity.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Joseph_Haydn%2C_m%C3%A5lning_av_Thomas_Hardy_fr%C3%A5n_1792.png image_description=Franz Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy, 1792 product=yes product_title=Franz Joseph Haydn: The Seasons product_by=Gabrieli Consort & Players. Paul McCreesh, conductor. Christiane Karg, soprano; Allan Clayton, tenor; Christopher Purves, baritone. Barbican Hall, London, Saturday 14th January 2010. product_id=Above: Franz Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy, 1792.Charpentier and Purcell by Early Opera Company

Based upon a story from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, this ‘pastorale en musique’ tells the tragic tale of the unfortunate eponymous hunter who unwittingly stumbles upon the secluded bathing haunt of the goddess Diana and her attendant nymphs. He attempts to conceal himself but to no avail, and he is punished severely for his trespass by the angry goddess. Diana transforms him into a stag and Actéon is pursued and torn apart by his own hunting hounds.

It is a fairly lightweight piece, with some dramatic variety and pleasing emotional contrasts; Charpentier’s score is typically elegant, with regard to melodic phrasing, and rhythmically robust, most especially in the bucolic scenes enlivened by dance-like instrumental forms and textures. Here, the assembled soloists emerged from the one-per-part chorus, deftly moving to the forestage at appropriate points, skilfully diverting and sustaining the audience’s attention. All produced a fairly idiomatic pronunciation of the French text; but, while a graceful phrasing of the exquisite yearning phrases was achieved, there was little attempt to render the authentic ornamentation of the French baroque style.

Charpentier, an accomplished tenor, probably composed the title role for himself. Here, Ed Lyon, singing confidently and with obvious commitment to the drama, produced a beautiful youthful tenor, surely sufficiently warm and tender to melt even the most glacial goddess’s heart. If Lyon’s upper register sometimes lacked a little weight and substance, the touching vulnerability of his tender pianissimo in his transformation scene more than compensated; and, he exalted Diana’s loveliness with wondrous awe. His transformation aria was followed by a trio sonata for violins and continuo, exquisitely played by violinists Kati Debretzeni and Huw Daniel supported by Reiko Ichise on viola da gamba.

As Diana, Claire Booth sang with focus and clarity, but while she was admirably reliable in pitch and tone, at times she seemed a little too forceful for the role. The heart-rending action was rudely interrupted by the interjections of Juno (Hilary Summers), who confesses that, in a jealous rage aroused by Jupiter’s infidelity, she has brought about Actéon’s death. Summers enjoyed the extravagant dramatic aspects of the part, projecting powerfully from the Wigmore Hall balcony; but, her tone was rather strident and somewhat undid the mood of elegiac pathos.

Ciara Hendrick and Elizabeth Weisberg completed the line up of competent soloists; the seven singers joined to form a chorus characterised by neat ensemble, and clean, airy textures. After Actéon’s death, his hunting companions lament “the beautiful days cut short” of this invincible hero “in the springtime of his age”; unfortunately some poor flute intonation unsettled the overall tuning at the close of what had been an appealing and convincing performance of an attractive and stirring score.

Charpentier’s Actéon is an unusual yet complementary pairing with Purcell's Dido and Aeneas, the latter being inconveniently succinct and requiring a partnering work. Yet, Charpentier’s score preceded Purcell’s by only five years, and there are many affinities between them, not only of musical style - Purcell’s dance-textures and rhythms often sound distinctly French - but also of situation and mythic context, for Charpentier’s narrative is also related by one of Dido’s ladies-in-waiting in the aria “Oft she visits this lone mountain” in Purcell’s opera.

If Charpentier’s pastoral drama is ultimately rather frivolous, Purcell inspires considerably greater emotional weight and intensity. With Anna Stephany, the advertised Dido, indisposed, Susan Bickley stepped into the role at short notice, presenting a controlled, poised interpretation of regal bearing, betrayal and distress. If her early arias seemed overly guarded and reserved, a little lacking in affective gesture, by the closing lament her noble dignity was firmly established and her portrayal deeply poignant.

Claire Booth was a deliciously rich-toned Belinda, and Hilary Summers’ vocal exaggerations were more apt for the disconcerting devilry of the Sorceress. As Aeneas, baritone Marcus Farnsworth, made as much as is possible of the slim part.

Christian Curmyn led the ensemble in typically controlled and elegant fashion; perhaps his rendering was a little too restrained, more suitable for Charpentier’s relatively inconsequential drama, than for the emotional peaks and troughs of Purcell. There was grace and discipline, but few musical or dramatic surprises; in the Purcell especially, the emotional peaks were somewhat muted, the protagonists a little too self-possessed. Even in the Charpentier the dances lacked spontaneity; one longed for a looser rein which would permit the instrumental players the necessary freedom to inject an improvisatory quality. Purcell’s drunken sailors and grotesque witches were distinctly reserved.

Although we don’t know the circumstances and venue of the first performance of Charpentier’s Actéon, its brevity and intimacy, and the courtly ambience of the French baroque idiom, suggest a private setting. Similarly, while it was once firmly believed that Purcell’s opera was composed for girls’ school in Chelsea run by dancing master Josiah Priest, critics now question whether it was not in fact modelled upon John Blow’s masque, Venus and Adonis, and first performed at court in the 1680s. Whatever their origins, both works are ideally suited to the intimacy of the Wigmore Hall, and the Early Opera Group’s thoughtful, if rather conservative, performance, heightened the grace and eloquence of these elegant, affecting scores.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Acteon_Diana.png image_description=Actaeon Surprising Diana by Titian (1556-59) product=yes product_title=Marc-Antonie Charpentier: Actéon; Henry Purcell: Dido and Aeneas product_by=Actéon — Actéon: Ed Lyon; Diane: Claire Booth; Junan: Hilary Summers; Daphne: Ciara Hendrick; Hyale/Arthébuze: Elizabeth Weisburg; Deux Chasseurs: Jeremy Budd, Philip Tebb.Dido and Aeneas — Aeneas: Marcus Farnsworth; Dido: Susan Bickley; Belinda: Claire Booth; Sorceress: Hilary Summers; First Witch/Second Woman: Elizabeth Weisberg; Second Witch: Ciara Hendrick; Spirit/Sailor: Ed Lyon.

Early Opera Company. Director/harpsichord: Christopher Curnyn. Wigmore Hall, London, Thursday 12 January 2012. product_id=Above: Actaeon Surprising Diana by Titian (1556-59)

Otello in Zürich

These two gentlemen were at it again just now in Zurich, Mr. Vick staging a new Verdi Otello and Mr. Hampson attempting its villain Iago, a late career role debut that did not even require him to change costume from his convincing, indeed moving portrayal of Rick, the professional soldier cum World Trade Center hero.

In Pesaro Graham Vick exploited the explosive hostilities of the Palestinians and Jews in such graphic detail that some audience fled the theater in terror. The Cyprus Greek Turkish tensions do not carry as much emotional baggage or fearsome consequences, at least in the international psyche, but like Mosé in Egitto the contemporary metaphor, here the on-going Cyprus problem, is too striking to ignore. All this is to say that Verdi’s old story, no longer old, was told in contemporary terms.

Unlike the huge ethnopolitical tragedies of Mosé in Egitto, Otello is a personal tragedy that unfolds in war torn Cyprus, though the visible ravages of war could be anywhere. Its opening chorus is not watching the battle but immersed in it by slathering black soot on their faces, stripping off clothes exposing white bodies parts as if wounded.

Fiorenza Cedolins as Desdemona

Fiorenza Cedolins as Desdemona

To preface the opera however, Otello, not in blackface, presented himself alone on the stage thus forcing himself into our close focus for the duration. Maybe it was the lack of the expected blackface that planted the seeds of racism in our minds, and Vick finally allowed overt racism to burst forth only in Act III when a suddenly exposed back-of-a-stage flat said “nigger.” But Vick had made it a black and white opera long before, and on multiple levels. Desdemona appeared in Act I as a phantom bride, a white veiled wife, who moved as if in an Otello dream, his dream of a world of beauty and purity, a sanctuary from the burned black colors of war.

Act IV, the Desdemona act, placed Desdemona in the center of a black stage. She re-entered the wedding dress, covered herself with the bridal veil and became again Otello’s dream as she sang her song and prayer, standing and immobile. We now knew and felt with certainty that this was Verdi’s opera as the Othello tragedy and not the melodrama of a fallen woman.

Acts II and III were in fact the Desdemona acts when she presented herself as an emancipated, worldly woman, possibly unfaithful, even defiant thus taunting the sensibilities of this Venetian general whose Asian sensibilities imagine his woman as veiled, like the burka covered women who praised Desdemona’s exposed beauty in Act II. The opera had suddenly gone globally political and we knew then that its tragically violent outcome was to be understood in universal as well as personal terms.

Judith Schmid as Emelia and Thomas Hampson as Iago

Judith Schmid as Emelia and Thomas Hampson as Iago

Where, you may ask, did Iago fit into all of this? This is where the Zurich casting choices for this remarkable Graham Vick production come into question. Tenor Jose Cura was a gruff, hulking, brutal Otello who held forth magnificently in high Italianate vocal style and whose high style method acting transported his Otello to admirable histrionic heights. Soprano Barbara Frittoli is young and shapely and a formidable Italianate singer whose personal beauty and beauty and range of voice fulfilled the gamut of Desdemona’s expressive needs in this complex concept.

Thomas Hampson simply did not fill the bill as Iago. His size and age precluded a physicality that could color and magnify and therefore interest us in the ugly insinuations Iago dishes out to Otello. In his army fatigues he seemed still the aged Rick Rescorla of the World Trade Center, towering over everyone, and shouting out accusations to Otello like instructions for evacuation. His nemesis Cassio, played by 24-year-old Stefan Pop was equally out of place in age and size, thus depriving this pivotal character of his essential weight and meaning in Verdi’s drama. Vocally however this young singer made the most of Verdi’s musical points.