September 30, 2014

Anna Caterina Antonacci, Wigmore Hall, London

Elegant and restrained, she did not need fancy costumes or extravagant gestures to convince of her star quality; instead, she drew us into the distinct world of each of the thoughtfully selected series of songs - by Respighi, Poulenc, Ravel and de Falla - by means of deeply expressive singing and detailed acting. Resting at times on the piano, she effectively embodied the songs’ personae and voices, and conveyed precise moods and sentiments.

Carl Orff is one of the classical music world’s ‘one-piece’ composers; how many could name any of his compositions other than Carmina Burana? And, those who are familiar with his intense, richly scored scenic cantata would probably find the suggestion that he had anything in common with the Renaissance sensitivities of Claudio Monteverdi an improbably proposition. However, Orff’s Lamento d’Arianna (after Monteverdi), composed in 1925 and subsequently revised in 1940, reveals more shared threads than one might imagine: Orff’s freedom of metre recalls the flexible declamatory style of the Renaissance madrigal and opera, and while their harmonic language may appear incongruous, the directness of the dramatic and rhetorical expression also unites the two composers. Such correspondences were movingly communicated in this rendering of Orff’s own piano reduction of his original orchestral score.The opening bars of Donald Sulzen’s piano introduction were, however, striking and attention-grabbing: grand and opulent statements, encompassing a wide tessitura, alternated with sparser more intimate gestures, creating a dynamic and moving rhetoric.

Indeed, Antonacci sensitively balanced tenderness and magnificence throughout the lament. Dynamics were finely graded and judged: in the first verse Arianna professes her desire to reject life, ‘In così gran martire’ (in such bitter suffering), a line which faded into a whisper, while her impassioned cry ‘O Madre, O Padre mio!’ glistened sonorously. Antonacci tamed her vibrato in the more introverted reflection but allowed the tone to bloom in anguished outbursts of accumulating intensity; Sulzen was an alert commentator, the jagged punctuation and huge spread chords of the final section effectively complementing Arianna’s grief-stricken apostrophising. After a powerful chordal piano postlude, the final, gently placed tierce de Picardie was a surprise: an unexpected note of consolation and peace.

When Orff presented arrangements of Lamento d’Arianna and another Monteverdi composition, Ballo dell’ingrate, the early music revival was just beginning in Europe, and interestingly at this time Ottorino Respighi made his own performing version of Monteverdi’s La Favola d’Orfeo. It was a fitting choice, therefore, to following the Orff with seven songs by Respighi, in which Antonacci frequently floated fine threads of soaring sound. Sulven was sensitive yet always unobtrusive; his precise, clear textures skilfully underscored textual details, as when evoking the translucent rippling waters of ‘O falce di luna’ (O crescent) or when - by means of nuanced harmonic inflections and suspensions, and an oscillating pattern in the middle voice - suggesting the dark hues of the abandoned garden in ‘Crepuscolo’ (Twilight).

Antonacci revealed not just her expansive tessitura but also her multi-coloured tonal variety: in ‘Acqua’ (Water) she modulated the weight and focus of her voice most expressively to convey the soft brushing of the whispering reeds wiggling along the bank (‘Acqua, e, lungh’essi I calami volubili/ Movendo in gioco le cerulee dita’) and a wonderful sense of lyrical freedom captured the fleeting motions of the water (‘Tu che con modi labii deduci’). In ‘Stornellatrice’ (Singer of Stornelli) alternate lines of burnished low mezzo and higher, lighter soprano effectively suggested the singer’s inner conflicts and questioning, before a self-possessed close: ‘Quando poi l’eco mi risponde: mai?’ (When the echo answers me: never?) A highlight of the sequence was ‘Sopra un’aria antica’ (On an old aria): again registral contrasts were employed to powerful effect and Antonacci delivered both the florid melodies and the detailed text emotively. Sulven’s delicate trills conjured a neoclassical air and served to meld old and new.

Poulenc’s seven settings of Paul Éluard which form La fraîcheur et le feu (The coolness and the fire) concluded the first half; these miniatures capture a multitude of moods and the performers moved easily from the fiery drama of ‘Rayons des yeux et des soleils’ (Beams of eyes and suns) to the lyrical expanse of ‘Le matin les branches attisent’ (The branches fan each morning). In the latter Antonacci once more demonstrated her vocal control, steadily withdrawing to suggest the tranquillity of the evening trees, ‘Le soir les arbres sont tranquilles’. In contrast, her glossy soprano swooped luxuriantly in ‘Tout disparu même les même toits le ciel’ (All vanished even the roofs even the sky) to suggest the glistening stars which mimic the singer’s tears, ‘Soeurs miroitières de mes larmes’. Sulven’s jazzy harmonies and parallel chords created drama and depth in ‘Homme au sourire tendre’ (Man with the tender smile), complementing Antonacci’s tone of tendresse.

A languid, silky rendition of Henri Duparc’s La vie antérieure (A previous life) followed the interval; the crescendo and accelerando in the second stanza powerfully conveyed the singer’s growing excitement, as reflected in the swells of the sea which create a ‘mellow music’, portrayed by Sulven’s low, grand gestures. After an impassioned outburst as she recalled her life of ‘sensuous repose’, Antonacci retreated into recollections of ‘Le secret douloureux qui me faisait languir’ (the secret grief which made me languish), her sadness sensitively evoked by Sulven’s long, poignantly unravelling postlude.

Ravel’s Cinq melodies popuiaires grecques were vibrant in their simplicity and directness. The ostinato patterns of ‘Le réveil de la mariée’ (The bride’s awakening) created an excited air of expectation, while the flattened seconds of the modal ‘Là bas, vers l’église’ (Down there by the church) were sensuously nuanced. Antonacci’s folky rhetoric in the unaccompanied ‘Quel galant m’est comparable?’ (What gallant can compare with me?) was delivered with confidence, an affirmation which found equal but contrasting voice in the free vocalise of ‘Chanson des cueilleuses de lentisques’ (Song of the lentisk gatherers). The exuberant repetitions, ‘Tra-la-la!’, and Sulven’s revolving patterns propelled ‘Tout gai!’ (So merry!) to a jubilant conclusion. In ‘Kaddish’, one of Ravel’s Deux melodies hebraïques, Antonacci’s strong mezzo voice captured the rapturous spirituality of the devotional sentiments, culminating in a hypnotic, melismatic ‘Amen’, while 'Vocalise-étude en forme de habanera' showcased her vocal flexibility and virtuosity.

Finally, we turned from Italy and France to Spain, Manuel de Falla’s Siete canciones populares españolas concluding the recital. Antonacci’s dramatic temperament was to the fore in these seven songs: the accusative fury at the end of the ‘Seguidilla murciana’ (Seguidilla from Murcia) was thrilling, while the sentiments of the quiet lament, ‘Asturiana’, were conveyed by Antonacci’s serene presentation of the sorrowful, restrained melodic contours, long even rhythmic values and by the unpredictable dissonances in the accompaniment. The asymmetries of ‘Jota’ (a lively Spanish dance) were playful and the vigorous rhythms were nimbly executed, while in ‘Nana’ (Lullaby) the singer’s melismatic phrase-endings had a charming ‘oriental’ colour. The final song, ‘Polo’, was brisk and passionate, Sulven’s persistent repeating patterns evoking the rhythms of a flamenco guitar, and the final heated and heartfelt ‘Ay!’ serving as a reminder that Antonacci has proven herself an impressive Carmen!

Claire Seymour

Anna Caterina Antonacci, soprano; Donald Sulzen, piano

Orff: Klage der Ariadne (after Monteverdi’s Lamento d’Arianna); Respighi, ‘O falce di luna’, ‘Van li effluvi de le rose’, ‘Sopra un' aria antica’, ‘Stornellatrice’, ‘Acqua’, ‘Crepuscolo’, ‘Pioggia’; Poulenc: La fraîcheur et le feu: Duparc: ‘La vie antérieure’; Ravel: Cinq mélodies populaires grecques, Deux mélodies hebraïques, Vocalise-étude en forme de habanera; Falla: Siete canciones populares españolas

mage=h

image_description=

product=yes

product_title= Anna Caterina Antonacci, soprano; Donald Sulzen, piano, Wigmore Hall London 24th September 2014

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=

September 29, 2014

Il barbiere di Siviglia, Royal Opera

There’s not much subtlety but plenty of mayhem and mischief, and this third revival, which brings together familiar faces and new voices, raised many a guffaw — and, for once, the laughter was prompted as much by the shenanigans on stage as by the surtitles aloft.

Making his Royal Opera debut as Count Almaviva, the Italian-American tenor Michele Angelini took time to settle. He seemed a little nervous and tense in ‘Ecco ridente’; the phrasing lacked elegance and there was some gruffness and untidiness. Similarly, ‘Se il mio nome saper voi bramate’ sounded strained at times. Certainly, Angelini has vocal agility — and physical nimbleness too, springing spryly into the branches of the baobab three beneath his beloved’s balcony. In the cascades each individual pitch was clearly defined, but there was some unnecessary ornamentation which could not compensate for a lack of creamy evenness and brightness. Indeed, Angelini over-complicated his Act 2 ‘Cessa di piu resistere’ too, tiring himself out in the process. But, he seemed more at ease in his Act 2 personae and enjoyed some effective comic romping as the billeted squaddie and fawning music master, wheedling himself deftly into his inamorata’s domain.

American baritone Lucas Meachem was more at home as the eponymous coiffeur, even though this was a Royal Opera role debut, and offered a master-class in comic singing and acting. Meachem has a huge voice but knows when to turn on the power and when to hold back, blending easily in the ensembles. Bellowing his arrival from the rear of the auditorium, Meachem then startled the amused audience, stopping to admire a hairdo or two as he strolled nonchalantly down the aisle. In a carefully paced ‘Largo al factotum’ every word of pithy patter rang clearly, delivered to the far nooks of the auditorium as Meachem seemed to make eye-contact will all. Throughout, this barber was irrepressible and engaging; the moments of exasperation and frustration were entirely natural and convincing. And, in ‘Dunque io son’ Meachem and his Rosina, Serena Malfi, relished the comic fun, Figaro ruefully recognising his equal in guilefulness as Rosina shrewdly whipped the pre-composed letter for ‘Lindoro’ from her bodice.

Malfi’s Rosina gave much pleasure. The Italian has a rich, warm mezzo, with a dash of velvety darkness. The coloratura demands were effortlessly dispensed, Malfi’s technical assurance allowing her to focus on communicating the drama. In ‘Una voce poco fa’ the petulance (stamping, pouting and dart-throwing!) were well-judged, and there was a feisty control about this Rosina that left no doubt that she was more than a match for her hapless guardian, Bartolo. Ebullient of character, voluminous of tone, Malfi sparkled in her house debut.

As her crafty custodian, Alessandro Corbelli returned to the role he sang in the 2009 revival and demonstrated that he has lost none of his buffo nous. In ‘A un dottor delta mia sorte’ Corbelli winningly delivered the musical and dramatic tricks; a perfect portrait of preening presumption, this Bartolo’s comeuppance was richly enjoyed.

The sinister edge in Maurizio Muraro’s full bass added vocal interest to Basilio’s ‘La calumnia’, complementing the predatory rage, while Welsh baritone Wyn Pencarreg (another ROH debut) was strong as Fiorello, quickly pinning the characterisation and singing cleanly and mellifluously.

This production indulges in hyperbole, and I found the shrieks and sneezes of Ambrogio (Jonathan Coad) and Berta (Janis Kelly) a bit tiresome; but Kelly charmingly revealed the secret yearnings beneath the housekeeper’s apparent disapproval of the amorous goings-on, in a sweet-toned ‘Il vecchiotto cerca moglie’. Promoted, like Coad, from the ranks of the ROH chorus, Donaldson Bell and Andrew Macnair acquitted themselves very well as the Officer and Notary respectively.

Having conducted the original run in 2005, Mark Elder returns to the pit, leading the ROH orchestra in a detailed, nuanced performance. The overture’s Andante maestoso was stately, perhaps a touch on the slow side, but the textures were clear and there was some lovely playing, and an expertly controlled trill, from the horn. Things picked up niftily, though, at the Allegro vivace and the final Più mosso was not so much a Rossinian acceleration as a Mo Farah-style final-lap kick, a ferocious injection of pace that initially left a few instrumentalists trailing behind.

I’ve seen this production twice before, and on each occasion the Act 1 finale has come adrift with the ensemble between the stage and pit as wobbly as the Keystone-Cop capers on the tilting stage, as the PVC-caped coppers sway and swoon. Elder took things steady — which made the anarchy on stage even more surreal than Leiser and Caurier perhaps intended — but singers and players still parted company. Overall, though, Elder achieved clarity and nuance; the woodwind solos were drawn to the fore and complemented by stylish string playing, with controlled dynamic grading.

All in all, a surprisingly fresh and engaging revival.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Count Almaviva, Michele Angelini; Figaro, Lucas Meachem; Rosina, Serena Malfi; Doctor Bartolo, Alessandro Corbelli; Don Basilio, Maurizio Muraro; Fiorello, Wyn Pencarreg; Berta, Janis Kelly; Ambrogio, Jonathan Coad; Officer, Donaldson Bell; Notary, Andrew Macnair; Directors, Patrice Caurier and Moshe Leiser; Revival Director, Thomas Guthrie; Conductor, Mark Elder; Designer, Christian Fenouillat; Costume Designer, Agostino Cavalca; Lighting Designer, Christophe Forey; Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Friday, 19th September 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ROH_1413.png image_description=Michele Angelini as Count Almaviva and Serena Malfi as Rosina © ROH [Photo by Tristram Kenton] product=yes product_title=Il barbiere di Siviglia, Royal Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Michele Angelini as Count Almaviva and Serena Malfi as Rosina © ROH [Photo by Tristram Kenton]September 26, 2014

September 19, 2014

Gluck and Bertoni at Bampton

Required to devise a fitting entertainment to celebrate the second marriage of Archduke Joseph, later Emperor Joseph II, to Maria Josepha of Bavaria, at Schönbrunn in 1765, Gluck offered his regal employerIl Parnaso confuso, a perfectly proportioned single-act setting of a libretto by Metastasio typically drawn from Classical mythology. The action takes place on Mount Parnassus, home of the Muses, where Melpomene (Muse of Tragedy), Erato (Muse of Lyric Poetry) and Euterpe (Muse of Music) lethargically idle the hours away among the sacred groves. The lazy spirits are robustly roused from their lassitude by the arrival of the god, Apollo. With urgency, he shakes them abruptly from their indolence and demands that they compose celebratory entertainments for the earthly marriage of Emperor Joseph and his "stella bavara" (star of Bavaria). Moreover, their creative offerings are required by the very next morning.

Alarmed by the swift invention and resourceful demanded of them, the Muses’ self-doubt is complicated by their competitive drive to outshine each other. And, just when they have put aside their petty jealousies, their brief harmonious collaborations are rudely disrupted by Apollo’s frantic reappearance: the mortal marriage has in fact already taken place and they must present themselves at the matrimonial festivities … now!

Metastasio’s text is atypically ‘light-hearted’, full of topical and self-referential jests: for example, the Muses agonise over the short time available to put the piece together. (Metastasio also takes the opportunity to ridicule two earlier festa teatra by Gluck, Le nozze d’Ercole e d’Ebe and Tetide, the latter having been composed for the Joseph’s first marriage to Isabella of Parma in 1752. Neither had employed a libretto by Metastasio and the Muses resentfully dismiss these works as old-fashioned and uninventive.) It is a perfect vehicle for director Jeremy Gray’s characteristic dry wit. I saw Bampton’s Bury Court performance in August, but — despite the limitations of the stage space and acoustic at St John’s — this performance seemed to me even more persuasive and dramatically engaging.

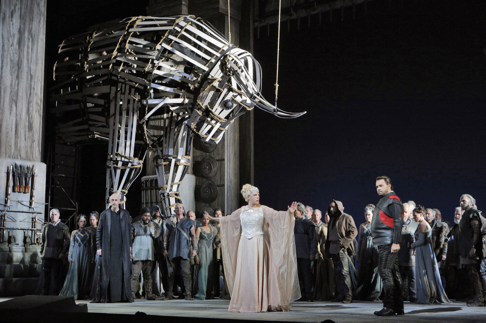

Orfeo, Euridice, Imeneo and Blessed Spirits

Orfeo, Euridice, Imeneo and Blessed Spirits

The cuckoo clocks and alpine vistas — a sideways glance at the location of the first performance — inform us that we are in the Swiss Alps; the cool blue lighting casts a glacial glow. The Muses are malingering languidly in a high-altitude hostelry until the arrival of ‘Fritz’ (the dull-witted tavern host, a silent addition to Metastasio’s cast, entertainingly played by Dudley Brewis), bearing a wicker basket of amusements triggers, some self-indulgent frolicking, skipping ropes and chocolate hearts keeping the idle artists occupied. Their trivial inconsequentialities coincide with the commencement of the overture, the bright strains of CHROMA, under the baton of Thomas Blunt, rising from behind stage screens adorned with snowy panoramas.

The idiosyncrasies and foibles of the three Muses — Melpomene (Muse of Tragedy), Erato (Muse of Lyric Poetry) and Euterpe (Muse of Music) were clearly delineated by Gray’s detailed direction and expertly embodied, dramatically and musically, by soprano Gwawr Edwards and mezzo-sopranos Anna Staruskevych and Caryl Hughes, respectively. The demanding, florid writing of Melpomene’s aria, ‘In un mar che non ha sponde’, requires much control, flexibility and stamina. (At the first performance, the four solo roles were taken by four royal princesses — Maria Elisabeth, Maria Amalia, Maria Josepha and Maria Carolina — the youngest of whom was no more than thirteen years old — and Maria Elisabeth, in particular, must have had real vocal talent to meet the challenges of Melpomene’s elaborate arias.) Edwards demonstrated superb breath control, encompassing the long, twisting lines effortlessly, and her gleaming, focused tone conveyed Melpomene’s haughtiness and ‘preciousness’ perfectly. She deftly balanced hauteur and humour, donning fluffy white ear-muffs to drown out her rivalries trivial pursuits and scorning Apollo’s offer of a restorative swig from an outsized tankard; but, Edwards also suggested a genuine melancholic sensibility in the heart of the tragic Muse when, dismayed and morose, she threatened to lay down her pen forever.

Staruskevych engagingly indulged in some mischievous larking about as the happy-go-lucky Erato but complemented blitheness with elegant phrasing and a rich, expressive mezzo tone. After some ham-fisted grappling with Euterpe’s lyre, Staruskevych gracefully communicated Erato’s lyric prowess, supported by a warm, elegant pizzicato accompaniment supplemented by entrancing violas and melodious solo bassoon. Hughes was a resourceful Euterpe, her soprano agile and bright, although occasionally I felt that she was a little under the note. But, she had calm presence in her graceful aria, unflustered by Fritz’s fruitless wrestling with her alpenhorn, and blended well with a lovely oboe obbligato.

Aoife O’Sullivan was outstanding as Apollo, boisterously interrupting the slothful Muses with a flourish of gold cape and a rousing call for creative ingenuity. O’Sullivan’s sweet-toned soprano is relaxed and warm across a wide register and she sensitively shaped the vocal phrases, especially when supporting the higher-lying line of Edwards in their closing duet. O’Sullivan can spin a mean trill too: and was no less adroit when whizzing the alka-seltzer to accompany Edwards’ own sparkling cadential embellishments.

The Orfeo myth may most immediately bring Gluck’s own 1762 opera, but on this occasion it was Bertoni’s 1776 account of the musical demi-god’s mythic mission which completed the operatic pairing on this occasion. In fact, it was at the behest of the castrato Gaetano Guadagni who had created the title role in Gluck’s opera that Bertoni commenced composition of the work; he acknowledged the debt he owed to Gluck, and there are some familiar moods and musical echoes.

Starushkevych was the eponymous quester and O’Sullivan the Euridice whom he pursues and seeks to restore to life; and the two principals and chorus (Edwards and Hughes were joined by tenor Thomas Hereford and baritone Robert Gildon and additional actors) beautifully captured the tenderness and solemnity of Bertoni’s score. The directorial details of the opening scene also did much to convince and engage the listener: sombrely attired mourners have gathered in a subdued chapel to grieve for the lost Euridice, and when Orfeo’s anguish overcomes him a fellow mourner imperceptibly intervenes to steer their choral lament to a consoling conclusion. In this instance the venue was an asset, the imposing columns and cool, shadowy reflections lending an air of restrained formality.

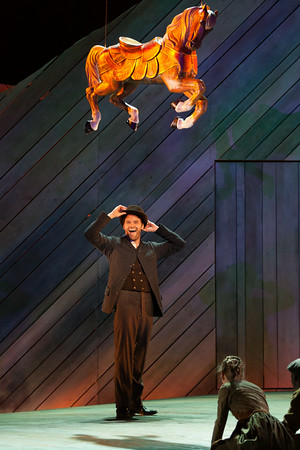

But, despite the gloom, there were flashes of directorial wit and visual gags to temper the despondency: a street new-seller hopes the day’s headline - ‘Snake Death: The Verdict!’ — will tempt a few passers-by, while Orfeo encounters not a raging Styx on his descent to Hadean realms but a team of road-diggers bearing ‘No Entry’, ‘One Way’ and ‘Narrow Road’ signs. A simple lighting design, contrasting infernal red and Elysian green, neatly underpinned the musical narrative.

In the title role, Starushkevych demonstrated why she won the 2012 Handel Singing Competition and also Bampton’s own inaugural Young Singers’ Competition in 2013. She exhibited excellent musico-dramatic nous and vocal stamina. This was a moving performance, in which the mezzo soprano drew upon her wide range and rich tone — her middle register is especially warm and firm — to inspire pity and affection; particularly moving was Orfeo’s third-act lament, accompanied sensitively by oboe, horns and strings. As Euridice, O’Sullivan sang with effortless ease: her airs danced freely and captured Euridice’s purity and innocence. The protagonists’ voices melded affectingly in their Act 3 duet. At Bury Court I had found Hereford’s characterisation of the role of Imeneo (in this production, a priest) a little understated, but here he was more animated — a wise and patient spiritual advisor, consoling and inspiring the bereaved Orfeo. Hereford also projected more effectively than at Bury Court, thus giving greater credibility to his role.

The entire cast communicated Gilly French’s economical and direct translation clearly. The diction was especially clear in Gluck’s secco recitatives which were stylishly accompanied by harpsichordist Charlotte Forrest. Placed behind the stage-screen panels which formed the simple set (in the second half, cold, grey bricks replaced the Alpine ice-peaks), conductor Thomas Blunt and the musicians of CHROMA maintained very good ensemble with the singers in the Gluck, although the Bertoni was less precise in this regard. Perhaps the cast tired a little, or maybe the more complex musical structures and accompanied recitative adopted by Bertoni presented fresh challenges.

But, once again, Bampton Classical Opera made a typically persuasive case for these neglected rarities, skilfully balancing wry irony with serious music-making.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Aoife O’ Sullivan, soprano; Gwawr Edwards, soprano; Caryl Hughes, mezzo soprano; Anna Starushkevych, mezzo soprano; Thomas Herford, tenor; Robert Gildon, baritone; Jeremy Gray, director/designer; Thomas Blunt, conductor; CHROMA. Bampton Classical Opera. St John’s Smith Square, London, Tuesday 16th September 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ba%3Bmpton_2014_02.gif image_description=Apollo, Euterpe, Melpomene (Gwawr Edwards) and Erato product=yes product_title=Gluck and Bertoni at Bampton product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Apollo, Euterpe, Melpomene (Gwawr Edwards) and EratoPurcell: A Retrospective

The eight singers (two sopranos, three tenors and three basses) assumed a variety of solo roles during the evening — roles which made contrasting technical demands and required a range of vocal registers and colours — and also united to form the ‘chorus’. The sixteen instrumentalists proved similarly chameleon in providing diverse accompanying textures and material in order to capture a gamut of dramatic moods. Christophers himself was the embodiment of musical joyfulness, guiding his players with lightness and grace.

The principal work presented was Purcell’s The Indian Queen which is usually termed a ‘semi-opera’. In fact, it contains much less music, dancing and spectacle than the composer’s other semi-operas, such as King Arthur, and is perhaps better described as incidental music for a play. Theatre politics and rivalries were responsible for the less elaborate form: the underpaid and disgruntled actors of the United Company (which, in the preceding few years, had staged Dioclesian, King Arthur and the Fairy Queen to great acclaim), led by Thomas Betterton, petitioned the King for permission to set up their own breakaway company. Ironically, their licence was granted by Sir Robert Howard, monitor of theatres for the Crown, who had been promised a revival of one of his dramatic works if he denied the rebels their request; as a consequence, the text of The Indian Queen was heavily trimmed, resulting in a much less satisfactory drama than Howard and his brother-in-law, John Dryden, had created 30 years earlier.

Set in Mexico (the Indies of the title) and Peru, it tells the tale of Montezuma’s ascent to the throne of Mexico, a convoluted path to power which embraced both fierce military battles and intense amorous rivalries. Some sprightly instrumental dances — played with clean, airy textures and sprightly rhythms — and a catch, ‘To All Lovers of Music’, introduced the sung Prologue in which an Indian girl and boy wake to find their country at war. Framed by a bright Trumpet Tune, the interchanges between tenor and soprano were supple and there was an easy fluidity as the individual sections unfolded. In the Act 2 masque of Fame and Envy, in which the Indian Queen Zempoalla’s inner conflicts are given outward expression — as her glory is eroded by jealousy and remorse — was characterised by the crystalline counterpoint of strings, recorder and trumpet and the harmonious choral blend supporting the solo voices.

Ismeron’s impressive Act 3 prayer, sung by a bass, presented an impressively diverse array of moods; initially the high-lying declamatory lines were embellished by David Miller’s elaborated theorbo continuo, but as the incantatory passion mounted, expressive word-painting (‘Earthy dun that pants for breath’) and flowing melisma (‘That along the cliffs do glide’) conveyed the growing intensity of feeling. The chromatic ascent, ‘From thy sleeping mansion rise/ And open thy unwilling eyes;’ was beautifully controlled and sensitive. Yet more new colours evolved in the ensuing soprano aria, ‘God of Dreams’, the walking bass of the bassoon providing a composed foundation for the oboe’s counter-melodies. After a contrapuntal Trumpet Overture, the duet for Aerial spirits was one of the highlights of the evening, the pure, glowing sopranos of Julie Cooper and Kirsty Hopkins complementing each other melodiously: dignified and elegant, the sopranos drew forth the telling nuances of the score, such as the shift to the minor tonality and slight pause in the phrase, ‘Cease to languish then in vain/ Since never to be loved again’.

Following the symphonic Air (Act 4), the final chorus of Act 5 was exquisitely crafted, inspiring pity and compassion for the historical sacrificial victims. Throughout, the choral passages were notable for clean textures and a seamless interplay of voices; diction was uniformly superb. Both singers and instrumentalists observed Purcell’s sometimes idiosyncratic rhythms precisely, but without rigidity; there were affecting contrasts between passages of legato grace and the vibrant syncopations of the scotch-snaps — the latter were repeatedly complemented by bite and brightness in the violins.

Born the son of a musician in Charles II’s retinue, Purcell himself went on to serve a series of regal employers — Charles II, James II and William and Mary — as chorister, organist, assistant organ builder, keeper of the King’s instruments, and supplier of festive anthems and odes for royal coronations, birthdays, weddings and repatriations. The first half of the concert presented some of these court commissions.

‘Swifter, Isis, swifter flow’, written to celebrate the return of Charles II to London from his annual sojourn at Newmarket, was only the second ode Purcell wrote. Once again, changes of tempi and mood were convincingly rendered; after the solemn opening symphony, with its subtly inflected falling chromatic harmonies, the fleet instrumental runs were agile and vibrant. The two recorders accompanying the bass solo ‘Land him safely on her shore’ evoked a wistful mood; the tenor air ‘Hark, hark! Just now my listening ears’ was especially engaging, commencing with a ringing vocal appeal, foreshadowing the bells which welcome back the returning monarch: ‘Let bells ring, and great guns discharge,/ Whilst numerous bonfires banish the night.’ The text of the concluding couplet of ‘Welcome, dread Sir, to town’ — ‘Your Augusta [London] will never be/ From your kinder arms debauched’ — was sensitively conveyed, such delicacy contrasting with the imperious and Italianate florid bass recitative of the subsequent air, ‘But with as great devotion meet’. An even, flowing legato enhanced the duet ‘The King whose presence’, the vocal lines once again underpinned by a smoothly running instrumental bass. The rich, grand chorus, ‘Then since, Sir, from you all our blessings do flow’, made for a grand, triumphant closing cry: ‘Long live the King!’

A sombre soprano duet ‘O dive custos Auriacae’, composed on the death of Queen Mary, followed; once again the soprano melodies mingled and rippled silkily, the surprising discords and angular lines adding piquancy to the sentimental lament. At its first performance The Indian Queen was followed by Daniel Purcell’s The Masque of Hymen. Here, the order was reversed, the masque ending the first half of the concert; ribald comedy — the married couple complain to the God of matrimony: ‘You told us indeed you’d heap blessings upon us,/ You made us believe you, and so have undone us.’ — preceding touching tragedy.

The concert was initiated in rousing fashion by cellist Joseph Crouch leading his fellow instrumentalists in a boisterous rendition of the catch ‘God save our sov’reign Charles’, an animated song which wryly refers to Charles’s dislike of his brother James, a Roman Catholic convert, who was exiled by Charles: ‘Preserve York’s duke, our King’s illustrious brother:/ Who to his pious votes denies his hand, I pray for him too, but wish him out o’ th’ land’!

Purcell was only 36 years old when he died; as with Mozart, Schubert and other prodigious musical talents of the past, we can only wondered ‘might have been’ had his musical voice not been so prematurely silenced. Yet, despite this, Purcell’s legacy is unique in English music and on-going; on this delightful occasion, Christophers and his musicians — the singers placed behind the instrumentalists but projecting efficiently — unquestionably communicated the delicate beauty and affecting power of his music.

Claire Seymour

Programme and performers:

Henry Purcell: ‘God save our sov’reign Charles’; ‘Swifter, Isis, swifter flow’ (Welcome Song for King Charles II); ‘O dive custos Auriacae domus’; Daniel Purcell: The Masque of Hymen; Henry Purcell: The Indian Queen.

The Sixteen Choir and Orchestra. Conductor, Harry Christophers; Violin, Sarah Sexton, Huw Daniel, Graham Cracknell, Daniel Edgar, Jean Paterson, Sophie Barber; Viola, Martin Kelly, Stefanie Heichelheim; Cello, Joseph Crouch, Imogen Seth-Mith; Oboe/Recorder, Anthony Robinson, Catherine Latham; Bassoon, Sally Jackson; Trumpet, Robert Farley; Harp, Frances Kelly; Theorbo/Lute/Baroque Guitar, David Miller; Organ/Harpsichord, Alastair Ross; Soprano, Julie Cooper, Kirsty Hopkins; Tenor, Jeremy Budd, Mark Dobell, Matthew Long; Bass, Ben Davies, Eamonn Dougan, Stuart Young. Wigmore Hall, London, Wednesday 17 th September 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Henry_Purcell.jpg image_description=Henry Purcell [Source: Wikimedia] product=yes product_title=Purcell: A Retrospective product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Henry Purcell [Source: Wikimedia]Mahler: Symphony no.3 — Prom 73

Unfair, because it would ignore the excellence of the playing and singing from the combined forces of Gerhild Romberger, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Children’s Choir, the ladies of both the Leipzig Gewandhaus Choir and the Leipzig Opera Chorus, and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra; but not because it would seriously misrepresent my impressions of Alan Gilbert’s conducting, nor indeed of his remarks in a programme interview. Mahler withstands, indeed rejoices in, a good number of interpretative options, and one should always be one’s guard, lest one reject, Beckmesser-like, something new, simply because it is something new. However, that does not mean that anything goes. The Achilles heel of Gilbert’s performance throughout was his lack of structural understanding, or at least his inability to communicate such understanding in performance. He seemed, indeed, to have taken Bernstein at his word — as opposed to following Bernstein’s excellent practice as a conductor — in the claim cited in that interview: ‘I heard Leonard Bernstein … rehearsing it once and he said: “You know what? Finally, after all these years, I’ve found the answer to this piece. It’s like a nightmare of marches. You shouldn’t try to connect them but just live in the moment.’ Perhaps you can do that once you have internalised the piece sufficiently, but, lack of score notwithstanding, Gilbert’s understanding seemed only superficial. As for his bizarre claim in that interview that there was no Viennese tradition of performing Mahler prior to Bernstein…

The first movement, then, sounded rather like Gilbert heard Bernstein described it, save for the fact that it was not very nightmarish. The Gewandhaus Orchestra played with greatly impressive attack, but seemed encouraged to sound brasher than usual, almost as if it were being asked to ape Gilbert’s — or Bernstein’s — New York Philharmonic. What was entirely lacking here was the formal inevitability — form should be understood in dynamic, not static, terms — one hears or has heard from conductors as different asAbbado, Boulez, Haitink, Horenstein, or indeed Bernstein. (I could have done without the Big Bird-style conducting gestures too; at one stage, I thought Gilbert was about to launch into flight. O for the elegance, the economy of the first three named of alternative conductors!) At least there was, for much of the movement, a strong sense of rhythm, even if its connection with harmony appeared to elude the conductor. That dissipated, however, with some unconvincing rubato and tempo changes later on, signalling instability in very much the wrong sense. Doubtless this will all be lauded as ‘exciting’ in some quarters, but without structural command, the excellence of the orchestral playing could not make a symphony out of what sounded more akin to a very lengthy suite. The rush to the finish, however, well executed by the players, was straightforwardly vulgar — as opposed to harnessing apparent vulgarity to higher ends.

The second movement strayed closer still to Simon Rattle territory (or rather recent Rattle territory). Necessary lilt soon became unduly moulded, variations in tempo excessive. Some material was taken very fast indeed, to the extent that it sounded almost balletic. Mahler as Delibes? A point of view, I suppose, but that is the best that can be said. The third movement veered weirdly between such ‘balletic’ tendencies and imitation Bernstein ‘house of horrors’, which would have been better left for the Seventh Symphony. The problem, really, was that they arose from nowhere, and that the whole movement was more than a little rushed. At least the post-horn solos were played beautifully — as indeed was everything else.

Gerhild Romberger gave an excellent rendition of ‘O Mensch!’ though she sounded very much a mezzo rather than a contralto. Hers was nevertheless a performance of compelling honesty, in which words and music amounted to considerably more than the sum of their parts. Gilbert’s conception, though restrained, I think, in the light of the soloist’s presence, seemed unduly ‘operatic’, missing the essential simplicity, however artful in reality, of this song. The fifth movement opened with as much coughing and shuffling as singing but, once that audience contribution was out of the way, the excellence of singing and playing alike could register. (That said, Romberger’s diction was noticeably less good here.) It was taken quickly, but at least it was not unduly pulled around.

Finally, the great Adagio — well, strictly speaking, Langsam — which came off surprisingly well. At least some of the time, it appeared to speak ‘for itself’. The Leipzig strings were wonderfully warm in tone, with the necessary depth to let Mahler’s harmony tell. Although it was not always as rhythmically solid as it might have been, the performance was a definite improvement upon most of what had gone before. And the sound of this great orchestra remained a wonder in itself.

Mark Berry

Gerhild Romberger (mezzo-soprano); Leipzig Gewandhaus Children’s Choir (chorus master: Frank-Steffen Elster); Ladies of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Choir (chorus master: Gregor Meyer); Ladies of the Leipzig Opera Chorus (chorus master: Alessandro Zuppardo); Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra/Alan Gilbert (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, Thursday 11 September 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/gustav_mahler.png image_description=Gustav Mahler product=yes product_title=Mahler: Symphony no.3 — Prom 73 product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Gustav MahlerLos Angeles Opera Opens with La traviata

On September 13, Los Angeles Opera opened its 2014-2015 season with a revival of Marta Domingo’s updated, Art Deco staging of Giuseppe Verdi’s La traviata. It starred Nino Machaidze as Violetta, Arturo Chácon-Cruz as Alfredo, and Plácido Domingo as Giorgio Germont. The conductor was Music Director James Conlon. During the overture a gentleman offered to accompany a rather reluctant lady standing under a streetlight. Then the curtain rose on Violetta’s opulent home. The contrast was enormous.

Machaidze looked gorgeous in her white 1920s “flapper” gown. Both she and tenor Chácon-Cruz started off slowly, but they came into top form in the Garden Scene of Act II. By that time they had relaxed and their voices blossomed. His “Deh miei bollenti spiriti” was smoothly spun out and he sang the cabaletta as if even its highest notes were easy for him. As the elder Germont, Domingo was stern with Violetta at first but showed his character’s softer side in a quiet moment. We missed his sun-drenched high notes, but he made a fine dramatic impression as a baritone.

Act III is the focal scene of this production and it was interesting to see the LA Opera Chorus dancing choreographer Kitty McNamee’s version of a Charleston to Verdi’s opening measures. Soloist Louis A. Williams, Jr. danced with spectacular height and spot-on landings. Here Machaidze, the “Twenties Violetta,” was in her element singing with silvered sounds, occasionally allied with the lustrous mezzo tones of Peabody Southwell, the Flora. As the enraged Alfredo, Chácon-Cruz showed his ire, but when castigated by his father, he collapsed into a heap on the floor. He and Domingo gave a fascinating portrayal of the relationship of a father to a grown son who still needs parental approval, whether he wants to admit it or not.

Louis A. Williams, Jr. (dancer)

Louis A. Williams, Jr. (dancer)

Machaidze was at her best in the final scene. Her reading of the letter and rendition of “Addio del passato” was heart wrenching. The audience felt the full meaning of her words, “è tardi” (it’s late). The letter came much too late for the fragile courtesan. When Alfredo finally comes to Violetta, she has only one moment of pure joy before lapsing into unconsciousness.

Vanessa Becerra, who sings a leading role on the recording of Daniel Crozier’s new opera, With Blood, With Ink was the caring attendant. Bass Solomon Howard, who will make his Metropolitan Opera debut as the King in Aida later this season, was an impressive Dr. Grenvil.

Music Director James Conlon conducted with great regard for the needs of the singers. Chácon-Cruz’s voice is not very large but it has a sweet, lyrical tone. Conlon made sure that the orchestra never covered his sound. The work of the Los Angeles Opera music director is one of the best reasons for attending the company’s performances. He makes each production of a popular opera say something new, no matter how many times it has been played.

After this evening’s performance, the opera presented Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky with an award for his service to the company. Since he had conducted the National Anthem, there were numerous jokes about his conducting ability, but he had earned the award by helping the opera get much needed funding from the city, which it has since paid back.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Conductor, James Conlon; Director, Marta Domingo; Lighting Director, Alan Burrett; Chorus Director, Grant Gershon; Choreographer, Kitty McNamee; Violetta, Nino Machaidze; Alfredo Germont, Arturn Chácon-Cruz; Giorgio Germont, Plácido Domingo; Flora, Peabody Southwell; Gastone, Brenton Ryan; Baron Douphol, Daniel Mobbs; Marquis d’Obigny, Daniel Armstrong; Dr. Grenvil, Solomon Howard; Annina, Vanessa Becerra; Solo Dancer, Louis A. Williams, Jr.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/La_Traviata_LA_2014_01.png

image_description=Arturo Chácon-Cruz as Alfredo and as Plácido Domingo as Germont [Photo by Craig Matthew]

product=yes

product_title=Los Angeles Opera Opens with La traviata

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Arturo Chácon-Cruz as Alfredo and as Plácido Domingo as Germont>br/>

Photos by Craig Matthew

Stars of Lyric Opera at Millennium Park, 2014

The concert featured works that will be part of the new season as well as selections of works that showcase the talents of the season’s singers and the Lyric Opera Chorus. Sir Andrew Davis conducted the Lyric Opera Orchestra on this evening, and the Lyric Opera Chorus was prepared by its director Michael Black.

The first half of the program featured two works that form part of the new season’s schedule: the Lyric Opera Orchestra played the overture to Tannhäuser (Dresden version) and a roster of six soloists performed the finale to Act II of Mozart’s Don Giovanni. In the overture the introductory alternation of brass and string parts was controlled smoothly; the transition to the solo for the first violin was especially well played, just as an overall tension built into the middle segment of the piece. In the concluding part of the overture Davis emphasized a unified, lush backdrop of strings while stately declamations from the brass led to the ending of the concert overture. The remainder of the concert’s first half introduced an ensemble of singers in Don Giovanni, which will open the 2014-15 anniversary season later this month, just as it began the first season sixty years ago. Mariusz Kwiecień sings the Don and Kyle Ketelsen his manservant Leporello; Donna Anna and Donna Elvira are sung by Marina Rebeka and Ana María Martínez; Don Ottavio was sung for this concert by John Irvin in place of an indisposed Antonio Poli; Zerlina and Masetto are performed by Andriana Chuchman and Michael Sumuel; the Commendatore / statua is sung by Andrea Silvestrelli. From the start of this ultimate scene and finale from Act II of the opera it was clear that an exciting, committed cast has been assembled for this new production. The interaction of Mr. Kwiecień’s Don, praising the banquet meal arranged for his epicurean taste, with Mr. Ketelsen’s Leporello assuring devoted service was entertaining and vocally taught. Kwiecień’s upper register was effective in suggesting an imperious and willful master, whereas Ketelsen’s deeper pitches in, e.g., “… che barbaro appetito!” underscored an amusing commentary. Indeed, as the other soloists joined in these final moments of Don Giovanni’s earthly existence, the multiplicity of emotions and personal destinies was interwoven into a large, vocal canvas. The efforts of Ms. Martínez to save her former seducer are expressed in yearning tones with appropriate embellishment as she pleads “L’ultima provo dell’ amor” [“The final test of love”]. When Giovanni refuses to reform, Elvira’s declarations of “Cor perfido” [“Faithless heart”] are sung by Martínez with credible forte pitches leading into a shriek when she, as the first, encounters the statua, or return of the slain Commendatore. This Don Giovanni’s cultivated, flippant tone in relation to both Leporello and Elvira changes, of course, when facing the challenge of the Commendatore. In the latter role Mr. Silvestrelli’s booming demands of “Risolvi!” [“Decide!”], and “Pentiti” [“Repent”] are a chilling ultimatum to the title character. Kwiecień responded with an acceleration of excited pitches in the vocal line culminating in his final shout of damnation. The concluding sextet reunites the two couples of Donna Anna and Don Ottavio, Zerlina and Masetto with Leporello and Donna Elvira. Both Ms. Rebeka and Mr. Irvin are fine exponents of Mozartean style; Mr. Irvin’s melodic line in “Or che tutti … vendicati” [“Now that all avenged”] was an excellent lead to Ms. Rebeka’s lyrical decorations in “Lascia, o caro” [“Allow me, my dearest”]. Both voices blended ideally in their verses “Al desio di chi m’adora” [“To the desires of one who adores me”]. Ms. Chuchman and Mr. Sumuel sang likewise in a convincing suggestion of renewed harmony. During the final lines of the sextet the female voices were especially well matched with a firm bass line sung by Ketelsen as a fitting backdrop.

The second half of the concert was introduced, just as the first part, with remarks delivered by the General Director Anthony Freud. The opening selections now featured the Lyric Opera Chorus in a familiar and in a less familiar excerpt. The latter piece, “Son Io! Son Io, la Vita!,” the Hymn to the Sun from Mascagni’s Iris with its locale fixed in legendary Japan. Touching lines, indicating sentiments such as “Through me the flowers have their scent,” alternated with lush, full scoring. The Chorus was well rehearsed throughout and it easily swelled upward to a glorious conclusion. The somber mood of “Patria oppressa” [“Oppressed homeland”] from Act IV of Verdi’s Macbeth was surely well captured in the second selection for the Chorus. A certain tension is, however, missing when the piece is not followed immediately by its usual, accompanying tenor recitative and aria (“O figli, o figli miei” [“O my children”]).

The two excerpts which concluded the evening brought onto the stage additional soloists as well as several from the first half of the concert. In the conclusion to Act I of Puccini’s Tosca Mark Delavan sang Scarpia’s final scene, “Va Tosca!,” together with the concluding Te Deum. John Irvin delivered the lines of Scarpia’s minion Spoletta. Mr. Delevan’s resonant baritone was fraught with emotion as he visualized the possible seduction of the singer Floria Tosca. As he repeated and lingered on the line “Va Tosca!” slight shifts in color indicated the growing anticipation of his desire. During the Te Deum in the church Delavan’s Scarpia was powerfully audible as he traced the line together with the Chorus. In the final selection, the last act from Verdi’s Rigoletto, Delavan sang the title role with Ms. Rebeka returning to sing the part of his daughter Gilda. The assassin Sparafucile and Maddalena were performed by Andrea Silvestrelli and J’nai Bridges. The Duke of Mantua was covered by Robert McPherson, who arrived in Chicago just before the performance to replace an ailing Mr. Poli. The trio of father, daughter and Duke made a promising start with McPherson sounding polished and at ease in “La donna è mobile.” He shows a good use of legato in the aria and sings excellent scales with decoration including an appropriate diminuendo; McPherson also holds the note on “pensier” without sounding forced. Ms. Bridges performed impressively as Maddalena both in her duet with Sparafucile and as part of the famous quartet. The volatility of the character Maddalena’s emotions is well suited to Bridges’s vocal range with ringing top notes used in pleading for the Duke’s life while her secure lower register was emphasized in rapid passages. The final scene between Rebeka and Delavan, as Gilda dies in Rigoletto’s arms, was movingly sung with ethereal, soft pitches suggesting indeed the daughter’s rejoining her mother in heaven.

The vocal splendors shared on this evening as a prelude or “appetizer” in Mr. Freud’s words certainly anticipate a fulfilling anniversary season to come at Lyric Opera of Chicago.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/LYR140906_069.png

image_description=(L.-R.) Kyle Ketelsen/Leporello, John Irvin/Don Ottavio, Marina Rebeka/Donna Anna, Sir Andrew Davis, Ana Maria MArtinez/Donna Elvira, Andriana Chuchman/Zerlina, Michael Sumuel/Masetto, from Don Giovanni finale [Photo by Todd Rosenberg]

product=yes

product_title=Stars of Lyric Opera at Millennium Park, 2014

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: (L.-R.) Kyle Ketelsen/Leporello, John Irvin/Don Ottavio, Marina Rebeka/Donna Anna, Sir Andrew Davis, Ana Maria MArtinez/Donna Elvira, Andriana Chuchman/Zerlina, Michael Sumuel/Masetto, from Don Giovanni finale [Photo by Todd Rosenberg]

September 18, 2014

Susannah in San Francisco

It is an opera some of us may now find to be a naive or simplistic artifact, nevertheless emblematic of those years.

Vanessa (1957), West Side Story (1957), The Saint of Bleecker Street (1955), and Susannah (1956) are the survivors from that decade. Like Vanessa, Susannah is a morbid short story though Vanessa is urban, subtle and twisted while Susannah is rural, obvious and brutal. At first Susannah may seem a bit like verismo, Cavalleria Rusticana for example, but it lacks the single physical blow and emotional resolution, dissolving instead into a sea of musically unsupported judgmental ironies.

Like West Side Story, Susannah is musical theater moreso than it is pure opera. It is a series of relatively brief, showy musical numbers that each illustrate a single emotion or situation. Its few action scenes are in elaborated recitative that is not integrated into larger musical structures.

West Side Story and The Saint of Bleecker Street are urban Americana composed by sophisticated New Yorkers (Bernstein and Menotti). These were the plights of poor immigrant Americans with strong ethnic accents, and music that eschewed the then current European complex serialism in favor of popular idioms and traditional forms.

Susannah composer Carlisle Floyd was born in South Carolina. He was a tenured professor at Florida State University and later founded the Houston Opera Studio. He writes about the American south (both words and music) in verbal declaration for which a strong regional accent is taken for granted. His musical idiom combines easy flowing tonal music with a big folksy overlay (hymns and mountain tunes) spiced with a bit of glowing dissonance.

Susannah may be the second most performed American opera but there is an immense gulf between the artistic intelligence and power of Porgy and Bess and the blatant moralism of Susannah.

Neither Gian Carlo Menotti nor Carlisle Floyd pushed the artistic envelope sufficiently to be discussed in Alex Ross’ history of music in the twentieth century, The Rest is Noise (2007). But make no mistake, along with these other works Susannah too is an operatic masterpiece in its way, and it is a quite modest way.

Patricia Racette as Susannah, Raymond Aceto as Blitch

Patricia Racette as Susannah, Raymond Aceto as Blitch

Susannah was composed for the reduced circumstances of post WWII and as a populist work of art consistent with the socialistic artistic politic of the time. Premiered in Florida it quickly made its way first to the New York City Opera, “the people’s opera” and then to the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair where it represented American culture. One can only question the wisdom behind the choice of specific, ugly content to portray American life to the world at large.

Just now San Francisco Opera rolled out a handsome new production that filled the War Memorial Stage. Canadian stage director Michael Cavanagh with his designer Erhard Rom created splendidly realistic expanses of southern mountains with scrims and projections. These lovely photographic impressions of nature were at odds with a modernistic cross, a huge, neon lighted (it seemed) cross typical of modern suburban mega churches that loom over the revival meetings. It screamed naiveté of concept.

Roaymond Aceto as Reverend Blitch

Roaymond Aceto as Reverend Blitch

A similar conflict arose in the stage direction, Mr. Cavanagh alternated between the presentational naturalism of the hayseed presences of Susannah, her brother Sam and the church elders, and clumsy solutions to managing the presentational needs of the crowd scenes at the picnics and in the church. Also clumsy were the several times a character was asked to silently act out conflicting emotions while we musically waited from him to make up his mind. Mr. Cavanagh is less to blame for these unsuccessful moments than Carlisle Floyd.

Soprano Patricia Racette, long a Carlisle Floyd heroine, still pulls it off, even in this latter day essay as Susannah. Because la Racette is usually associated with the great roles in the grand repertory it seems a waste to cast her in such simple music. The same can be said of tenor Brandon Jovanovich who gave us a superb Sam, Susannah’s brother, his performance utilizing but a tiny percentage of his capability (Lohengrin in 2012 for example). Of the three principals only bass Raymond Aceto as the Reverend Blitch did not find an un-self conscious Americana presence, his performance was purely big house look-at-me opera singing and acting. The smaller roles were well cast.

This little opera can pack quite a wallop in the right circumstances. Susannah simply does not blow up to grand opera proportions.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Susannah Polk: Patricia Racette; Sam Polk: Brandon Jovanovich; Rev. Olin Blitch: Raymond Aceto; Mrs. Mclean: Catherine Cook; Little Bat Mclean; James Kryshak; Mrs. Hayes: Jacqueline Piccolino; Mrs. Gleaton: Erin Johnson; Mrs. Ott: Suzanne Hendrix; Elder Hayes: Joel Sorensen; Elder Gleaton: A.J. Glueckert; Elder Mclean: Dale Travis; Elder Ott: Timothy Mix. Orchestra and Chorus of the San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Karen Kamensek; Stage Director: Michael Cavanagh: Set Designer: Erhard Rom; Costume Designer: Michael Yeargan; Lighting Designer: Gary Marder. War Memorial Opera House, September 12, 2014, seated seventh row center.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Susannah_SF1.png

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Susannah in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Brian Jovanovich as Sam, Patricia Racette as Susannah [All photos by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

In Bruges

By John Yohalem [16 September 2014, Parterre Box]

They say that Boston, despite many cultural distinctions, ain’t no opera town, and for some decades—generations?—this has been true. But tides of change will break, even on the shores of the Hub. There is a baroque opera revival, spawned by the Boston Early Music Festival (a Monteverdi trilogy arriving next spring) and leading to hi-jinks at the region’s many schools, and to Boston Baroque, which gives Handel’s Agrippina in April. The somewhat traditional Boston Lyric Opera presents everything from Lizzie Borden (last month) to La Traviata (next month), though confining itself to three or four productions a year.

September 17, 2014

Xerxes, ENO

Receiving its 6th revival on 15 September 2014, revival director Michael Walling, the production is looking as fresh as ever with David Fielding’s designs still bright and crisp. ENO fielded a strong cast mixing experienced singers and newcomers. Mezzo-soprano Alice Coote sang the title role; an experienced Handelian this was her role debut. Having sung Atalanta in the last revival of the production (in 2002) Sarah Tynan moved onto sing Romilda, the more serious dramatic of the two soprano roles. The soubrette role of Atalanta was sung by Harewood Young Artist Rhian Lois, whilst another Harewood Young Artist, Catherine Young sang Amastris. Counter-tenor Andrew Watts sang Arsamenes, with Neal Davies as Ariodates and Adrian Powter as Elviro. Michael Hofstetter conducted.

Hofstetter is the Principal Conductor of the Grossess Orchester Graz and made his ENO debut with La Traviata. But his background is also in early music and he launched the overture at quite a considerable speed. The ENO Orchestra responded brilliantly but I did rather worry about the health of the performance. In fact, I need not have worried and Hofstetter proved a responsive conductor, keeping the show moving but never rushing the singers off their feet.

Whilst the production is in good health, I did rather worry that the general tone had become a little more flippant and satirical than formerly. I was assured by others present that this was not so; Nicholas Hytner was in the audience and reputedly was happy with the revival. It is, after all, 29 years since I saw the opening run with Ann Murray and Valerie Masterson and not only does memory play tricks but my own conception of Handelian opera seria has changed.

Rhian Lois as Atalanta and Andrew Watts as Arsamenes

Rhian Lois as Atalanta and Andrew Watts as Arsamenes

Not that Xerxes is in any way typical of Handel’s opera. Handel always seems to have had a fondness for using librettos taken from 17th century Venetian operas, but in Xerxes he seems to have kept rather closer to the original. The opera has far more short arias and far fewer extended da capo arias than is general in Handel. And, whilst the piece is not strictly a comedy, it does mix the serious with the satirical in a way which is sometimes downright comic. But getting the tone right is essential. When Act 2 comes, and we have all five principals (Xerxes, Romilda, Arsamenes, Atalanta and Amastris) having problems in love and addressing us in serious tones, it is essential that we believe in them as people. They might get up to comic business, but their emotions are very real. By and large Walling got this right.

Alice Coote’s Xerxes was superbly sung, covering the full range from the short lyric arias through the virtuoso bluff and bluster to the intense pain of the extended da capo arias. Coote has a very personal way with Handel and her performance was a very individual one. Musically she took her time over some things, but showed herself equally capable of bravura passagework. Similarly, in terms of character, she projected Xerxes’ changeability quite brilliantly. Her conception of Xerxes might be rather more flippant than some, but she certainly brought out the idea that living with him was very much living on the edge. You never knew what might happen.

Equally captivating and profoundly poised was Sarah Tynan as Romilda. She started out giving the character a lighter, slightly satirical edge as if she had not left Atalanta behind, but Tynan’s Romilda develop a superb depth. Tynan’s Handel singing is still crystalline and clear, with a lovely sense of style. In fact, the Romilda she reminded me of most was the original one in this production, Valerie Masterson. Tynan didn’t just sing superbly, but brought a real depth to the bleaker moments when Romilda says that if she can’t be with Arsamenes then she will die. Tynan made us believe it, whilst sounding superbly beautiful.

Adrian Powter as Elviro and Catherine Young as Amastris

Adrian Powter as Elviro and Catherine Young as Amastris

Rhian Lois, singing her first Handel opera role, was a great delight as Atalanta. Her coloratura was pin sharp and she was wonderfully sparky (perhaps too much so at first) but she also brought out the more serious moments when the mask slipped. And she developed a very vital relationship with Sarah Tynan’s Romilda. Perhaps Lois took a little time to work up a full head of steam, but that is understandable.

Also singing her first role in Handel opera, Catherine Young made a strikingly tall Amastris. She has a lovely soft-grained voice which you sense will become a great asset in a number of trouser roles; a Xerxes in the making. But Amastris was written for a robust contralto voice and there were moments when, though singing musically and intelligently, Young lacked the necessary heft.

Arsamenes is one of the characters in the opera who gets virtually no comic moments. Andrew Watts was suitably intense and, in the more lyrical arias with great beauty and a lovely sense of Handelian line. But in the more stressful arias, he had a tendency to push his voice too much so that a hardness crept in and there were rather too many acuti which would have been better missed out. This was a shame, because this was a performance of great strength and intensity.

Adrian Powter made a delightful Elviro with good comic timing. He gamely appeared in a dress for act two (definitely not on the original production) and with his beard and long hair, looked startlingly like Conchita Wurst. Neal Davies made what he could of Ariodates giving him a bluff idiocy which was entirely apt and singing the more bravura moments finely.

Hofstetter and the orchestra were on fine form throughout the opera, providing a crisp and nicely historically informed accompaniment.

This was an admirably strong revival, showcasing some extremely fine Handel singing and a production in robust health. Here’s to another 30 years.

Robert Hugill

Cast and production information:

Xerxes: Alice Coote; Romilda: Sarah Tynan; Atalanta: Rhian Lois; Arsamenes: Andrew Watts; Amastris: Catherine Young; Ariodates: Neal Davies; Elviro: Adrian Powter. Director: Nicholas Hytner; Revival Director: Michael Welling. Conductor: Michael Hofstetter. English National Opera at the London Coliseum, 15 September 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENO-Xerxes--Coote_Tynan.gif image_description=Alice Coote as Xerxes and Sarah Tynan as Romilda [Photo ENO / Mike Hoban] product=yes product_title=Xerxes, ENO product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: Alice Coote as Xerxes and Sarah Tynan as RomildaPhotos © ENO / Mike Hoban

September 15, 2014

San Diego Opera Opens 2014-2015 Season

This performance was at the Balboa Theater, a reconditioned movie house with good acoustics. The auditorium was full and the applause greeting Carol Lazier, President of the Board of Directors, and Nicolas M. Reveles, Director of Education and Community Engagement, was almost as loud as the sounds that were heard last spring when the company almost disbanded.

On Friday evening September 5, 2014, tenor Stephen Costello and soprano Ailyn Pérez gave a recital to open the San Diego Opera season. After all the threats to close the company down as was the wish of former General Director Ian Campbell, it was a great joy to great San Diego Opera in its new vibrant, if slightly slimmed down form. This performance was at the Balboa Theater, a reconditioned movie house with good acoustics. The auditorium was full and the applause greeting Carol Lazier, President of the Board of Directors, and Nicolas M. Reveles, Director of Education and Community Engagement, was almost as loud as the sounds that were heard last spring when the company almost disbanded. San Diego was willing to let everyone in the world know it needed its opera company. That’s why it got contributions from all over the globe.

Stephen Costello and Ailyn Pérez had just released a new compact disc Love Duets and San Diego was the first stop on their tour of the United States. With collaborative pianist Danielle Orlando, Pérez entered in an exquisite scarlet-lined pink dress to sing lines from Act I of Verdi’s La traviata. Costello soon joined her as he might have had the scene been staged. His stage deportment has improved markedly since the last time I heard him and his “Un di felice” was as beautifully phrased as I have ever heard it.

She continued with songs by Reynaldo Hahn and he returned with Jake Heggie’s Friendly Persuasions, a group of songs that pay homage to Francis Poulenc. In one song Wanda Landowska worries about his giving her a concerto to learn the last minute. In another Pierre Bernac describes Christmas in 1936. Poulenc remembers Raymonde Linossier saying that his notes “like iron filings are pushed and pulled by the magnetic force” of Paul Eluard’s words. Costello’s French diction was laudable and the colors of his tones conveyed at least as much meaning as the words. These are wonderful songs and I hope more singers will soon perform them.

Pérez then sang a charming excerpt from Massenet’s Manon and her voice blossomed with silvered tones. Costello reminded this audience of the performances of Faust they performed together with “Salut demeure chaste et pure” which he ended with an exquisite, well controlled pianissimo. They brought the recital to intermission with an amusing duet from Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore.

After the interval the couple and their accompanist returned to perform the well-known duet from Mascagni’s L’amico Fritz, for which Pérez’s Suzel wore some very form fitting polka dots. She followed the duet with seven de Falla songs: El Paño Moruno speaks of stained cloth as a metaphor for a young girl of loose morals. In the Seguidilla Murciana Perez speaks of male inconstancy while in her other songs the colors of her voice and the textures of her music told of universal human conditions that are as true today as they were in the composer’s time.

Costello’s solo contributions were a combination of well known and lesser-known songs by Paolo Tosti. Most of the audience knew his Ideale, but his Non t’amo piu and Goodbye were new to many. The latter was actually written in English. Perez and Costello brought the recital to a close with Bernstein’s One Hand, One Heart, and its close was greeted with thunderous applause for them and for Orlando, their most capable accompanist, Their possessive audience would not let them go without three encores: Youmans’ Without a Song, Obradors’ Del cabello más sutil, and Rogers’ If I Loved You.

Maria Nockin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Love_Duets.png

image_description=Ailyn Pérez and Stephen Costello [Photo courtesy of Warner Classics]

product=yes

product_title=San Diego Opera Opens 2014-2015 Season

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Ailyn Pérez and Stephen Costello [Photo courtesy of Warner Classics]

Otello at ENO

David Alden’s new production of Verdi’s Otello is a stirring exercise in chiaroscuro. Boito may have omitted Shakespeare’s first Venetian Act but the jarring opposition the inflammatory imagery which Iago hurls at Brabantio — ‘an old black ram/ Is topping your white ewe’ — is powerfully embodied in the bold juxtapositions and gargantuan shadows of Adam Silverman’s superb lighting design, in the electrifying musical contrasts conjured by conductor Edward Gardner, and in the incontrovertible opposition of the murderous Otello’s black attire and Desdemona’s white night-gown.

There is little colour. Designer Jon Morrell has constructed a claustrophobic, monochrome set: high stone walls tower over dusty grey cobblestones, shutting out the exterior world, although the imposing portico occasionally slides aside to give a glimpse of distant sunsets. Costumes are similarly muted: Otello’s dull mustard war-coat is soon cast aside for anonymous black worsted (indeed, there is little to distinguish this Otello visually from those around him); Iago dons heavy, dark leather; Desdemona is shrouded in flowing black folds. Only Cassio’s bright blue uniform and Emilia’s rust-brown coat and cloche hat alleviate the subdued palette. Tellingly, there is a flash of fire, and it is sparked by Iago’s dropped cigar at the start of the raucous drinking song — by these means, he ignites his Machiavellian plot. The small flaming brazier returns in the final scenes: Iago’s evil has kindled the flames of jealousy to their tragic climax.

Stuart Skelton as Otello and Jonathan Summers as Iago

Stuart Skelton as Otello and Jonathan Summers as Iago

There is much to admire in this production, not least some fantastic singing from chorus and soloists alike. In Act 1, the ENO Chorus roared with exhilaration when their triumphant commander’s sail was espied and greeted Otello’s arrival with a thrilling outburst of excited passion, as Turkish flags were unceremoniously shredded. But, the decision to have the Cypriots’ hymn of praise to the beautiful, pure Desdemona sung off-stage was somewhat odd, necessitating extra dancers to bestow gifts upon Desdemona, the strewn ragwort suggesting a garden milieu.

Peter Van Hulle’s Roderigo was a portrait of preening solipsism, his smooth tenor aptly mellifluous. Roderigo’s dandyish white suit and Panama hat presented a sharp foil to the prevailing darkness, as he flopped foppishly in the margins. As Cassio, Allan Clayton sang with sincerity, the warm sound open and full, the phrasing elegant and lyrical. Cassio’s essential grace and goodness — as Shakespeare’s Iago admits, ‘He hath a daily beauty in his life/That makes me ugly’ — was powerfully communicated. Barnaby Rea had real stage presence and imperious dignity as the Venetian senator, Lodovico, while Charles Johnston was a resonant Montano.

Pamela Helen Stephen’s strait-laced costume made Emilia seem rather reserved; and as there was little attempt by Alden to establish any sense of the relationships that Emilia has with her brutish husband or with her noble mistress, Stephen was left on the periphery dramatically. But, the mezzo-soprano sang with characteristic clarity and vividness, particularly when Emilia’s angry despair finally found passionate voice in the closing moments, and Stephen made the most of every opportunity there was for dramatic nuance.

Leah Crocetto has a big voice and she sang with unforced power and much lyric beauty as Desdemona, in what was her UK debut. Crocetto’s Desdemona had grace and refinement; she demonstrated a fine feeling for a Verdian line, although at times I found the wide vibrato overly mature — Desdemona has, after all, barely left childhood. Initially calm and self-assured, Crocetto suggested that she might serve as a path to redemption for Otello; indeed, this inference was strengthened by Alden’s inclusion of a recurring visual motif — an altarpiece Madonna which reminded us of Desdemona’s chasteness and angelic purity, as well as recalling the Roman Catholic Italy where the opera was composed. And, thus, in Act 3 when Iago dupes both Cassio and the concealed Otello, the darts that he flung at the icon cemented his demonic status.

Crocetto modulated her tone effectively during the ‘Willow scene’ and in her tragic tussle with the deluded, deranged Otello, as she strained to assert her innocence, candour gave way to resignation. Why, therefore, was this tragic dénouement not more affecting? One problem is the setting: Alden retains the outdoor locale of the previous three Acts, and the murder takes place not in the bedchamber but in the street. This weakens the trajectory of Shakespeare’s play, which moves progressively, with a gradual tightening of the dramatic focus, from large public spaces to ever more claustrophobic private interiors, culminating in the domestic bedroom.

Moreover, in both play and opera, Desdemona has been banished by Otello to this bedroom — that the tragedy occurs in a matrimonial chamber emphasises the nature of Otello’s weakness: honoured, esteemed and mighty martial leader he might be, but he is also ‘Rude … in my speech, And little bless'd with the soft phrase of peace’ — it is his inexperience in matters of the heart and home which allows Iago to deceive and manipulate his commander, for dishonour in his marriage will blemish Otello’s reputation and thus destroy the public persona that is his edifice against racial discrimination and abuse. It is true that the conflict in Verdi’s Otello has almost no racial dimension; but, this alteration does remove an important element in the characterisation. And, there are still anomalies which result from Alden’s alfresco setting, chiefly the absence of the bed upon which Desdemona bids Emilia to lay her marriage sheets and nightgown, and upon which she dies.

In their despair, Desdemona and Otello clutched at facing walls, as Iago perched on a be-shadowed chair, watching his handiwork unfold; thus Alden, by sending the protagonists to the extreme reaches of the stage, emphasised their emotional separation but this also distanced us from their suffering.

Indeed, Alden conveyed little sense of the all-consuming love which must have existed for Otello and Desdemona to dare to defy paternal, social and cultural mores. In the title role, Stuart Skelton sang with marvellous lyricism and expressive range, finding soft tenderness in his end-of-Act 1 duet with Desdemona (‘Già nella notte densa s'estingue ogni clamor’) and heroic anger in his Act 3 vengeance duet with Iago (‘Sì, pel ciel marmoreo giuro’), in which the garish smearing of the men’s faces with blood made for a striking and ironic image of brotherly loyalty and love. But, Skelton’s Otello was overwhelmingly a man alone, and the tragic tangle of relationships was only sketchily drawn. Despite the booming vocal sonority of his first entrance, and his impressive physicality, even at the start Skelton did not capture the majesty and stately grandeur of the man entrusted to lead the Venetians to victory over the Turks. (Perhaps English, ‘We have triumphed!’, doesn’t quite have the magnificent ring of Italian, ‘Exultate!’?) Instead, Otello seemed distracted and withdrawn, and the signs of impending disintegration were evidence from the first. Psychologically and socially, this Otello was above all else an outsider and there was throughout a Grimes-ian angst and instability in the flashes of violence (the chairs strewn around the stage were a reminder of Otello unpredictability) and, as he tossed his papers of state furiously into the air, his indifference to social authority and judgements. (The reference to the Pleiades in Tom Phillips’ translation only seemed to underscore the parallels.)

It seems that focusing on Otello’s existentialism was a deliberate directorial decision; in a programme interview, Alden explained, ‘I think the portrait of Otello in the opera is a very interior one. It’s not so much about the social context but rather about the life of this man’. But surely, as for Grimes, it is the simultaneous desire to belong and defy that is Otello’s undoing? Removing him from his context weakened our understanding of Otello’s feelings and our empathy for his anguish.

One who did convey the full range of his character’s emotional flaws and twisted motivations was Jonathan Summers as Iago. Summers found a different vocal timbre for each of Iago’s ‘masks’: gruff soldier, loyal ensign, suave trickster and violent, malicious malefactor. There may have been only brief snatches of Verdian poetry, but this was fitting for a man who has no poetry in his soul. Having closing the shutters to block out the light, Summers also delivered an angry, bitter Credo that convinced of the blackness of his heart. But, no sooner had his master reappeared, than this ensign was amiably and smoking a cigar, a relaxed façade veiling his inner depravity and crookedness.

Gardner summoned wonderful playing from the ENO orchestra, sweeping forward in a whirl of Verdian melodrama. Despite the excellence of many of the parts, this Otello did not quite add up to a complete and compelling whole, but it’s still an impressive and thought-provoking show.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Stuart Skelton, Otello; Leah Crocetto, Desdemona; Jonathan Summers, Iago; Allan Clayton, Cassio; Pamela Helen Stephen, Emilia; Peter Van Hulle, Roderigo; Charles Johnston, Montano; Barnaby Rea, Lodovico; Director, David Alden; Conductor, Edward Gardner; Designer, Jon Morrell; Lighting designer, Adam Silverman; Movement director, Maxine Braham; Orchestra and Chorus of English National Opera. English National Opera, London, Saturday, 13th September 2014.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Otello_ENO_2014_01.png image_description=Stuart Skelton as Otello and Leah Crocetto as Desdemona [Photo by Alastair Muir] product=yes product_title=Otello at ENO product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Stuart Skelton as Otello and Leah Crocetto as Desdemona [Photo by Alastair Muir]September 14, 2014

Anna Nicole, back with a bang!

My initial impression of the performance on February 17, 2011 was somewhat disappointing. Mark Anthony Turnage's opera is funny, yes, deliberately and ostentatiously rude. It subverts everything traditional opera stands for in its glitzy celebration of the vacuous, but on first acquaintance it seemed disappointing, if only because Turnage's previous output had been so impressive.