May 31, 2015

Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari: The Jewels of the Madonna

But the company’s music director and opera director is the Austrian conductor Friedrich Haider, who is something of a Wolf-Ferrari expert having recorded Wolf-Ferrari’s opera Il segreto di Susanna (Susanna’s secret) and the violin concerto, and the house has a large permanent ensemble with a big choir from whom it was possible to cast the large number of important comprimario roles.

Rather impressively the opera was double case and we saw the premiere at SND’s New Building on Friday 29 May 2015 with Kyungho Kim as Gennaro, Denisa Šlepkovská as Carmela, Natalia Ushakova as Maliella and Daniel Čapkovič as Rafaele, conducted by Friedrich Haider, directed by Manfred Schweigkofler with sets designed by Michele Olcese and costumes by Concetta Nappi. The SND Orchestra and Chorus, was joined by the Bratislava Boys Choir, and the Pressburg Singers.

Kyungho Kim as Gennaro

Kyungho Kim as Gennaro

The plot is relatively straightforward, Gennaro (Kyungho Kim) is a young blacksmith who has three obsessions, his mother Carmela (Denisa Šlepkovská), the Madonna and his foster sister Maliella (Denisa Šlepkovská). This latter is rather wild, wanting to enjoy life but is kept confined by her family. She is being courted by Rafaele (Daniel Čapkovič) the head of the local Camorra.

The first act centres on a celebration for the feast of Our Lady, with a gloriously chaotic series of processions and lots of street characters, including an appearance from the statue of the jewelled Madonna. Act two is in the courtyard of Gennaro’s home and is a series of interactions, between Gennaro and Carmela, Gennaro and Maliella, Maliella and Rafaele. we learn that Carmela’s protective mothering of Gennaro arose because she nearly lost him as a child, and the fostering of Maliella was the result of a vow to the virgin if Gennaro survived. Gennaro tells Maliella of his obsession and she laughs at him, he vows to steal the jewels of the Madonna for her. Later Rafaele comes courting and the two have a love scene through the grill locking Maliella in. Finally Gennaro reappears with the jewels and the act closes with Gennaro covering Maliella with jewels before claiming her virginity. Act three is Rafaele’s gang’s hangout; an orgy in progress is interrupted first by the arrival of Maliella, traumatised by Gennaro’s taking of her virginity, and then by Gennaro with the jewels themselves. Though the gang has been having an orgy beneath an image of the Madonna, they are shocked by Gennaro’s sacrilege. But Wolf-Ferrari knew Jung and was cleaarly interested in the madonna/mother/whore parallels, and it is clear that for Rafaele, Gennaro has stolen the jewels (virginity) of his madonna (Maliella), and Rafaele loses interest in Maliella.

Though I gioielli della Madonna is commonly linked to the later Verismo school, the opera has both dramatic and musical differences. True the story has the dramatic shock value of a Verismo opera, but Wolf-Ferrari is like Verdi in being interested in the consequences of actions. Operas like Pagliacci end with the major dramatic coup, in I gioielli della Madonna Wolf-Ferrari continues into the remarkable third act where we explore the tragic consequences of actions and it ends in a mysterious and unnerving manner with Maliella’s disappearance (and presumed death) and Gennaro’s suicide; no big climactic moment. Musically there are similar differences, and certainly none of the driving passion and big, throbbing, orchestra supported tunes from Verismo.

František Ďuriač as Rocco, Natalia Ushakova as Maliella and Peter Maly as Ciccillo

František Ďuriač as Rocco, Natalia Ushakova as Maliella and Peter Maly as Ciccillo

Wolf-Ferrari was of mixed Italian and German heritage, and German trained in Munich under Rheinberger. His eclectic style is allied to a complexity in the orchestration and structure which makes for richness (when premiered the opera was far more popular in Germany than in Italy). There are tunes a-plenty including popular ones echoing the street celebrations, but all are melded into a remarkable synthesis ranging from Saint-Saens to Richard Strauss, with pre-echoes of Stravinsky and Shostakovich. Rather imaginatively, the Camorra are not depicted by dark music but they make their entrance to a jolly tune on the mandolins, though this can turn threatening when the knives come out.

The plot really requires the opera to be set in the correct period and location, intense devotion to the Madonna is a core component. Director Manfred Schweigkofler and designers Michele Olcese and Concetta Nappi moved the time forward to the 1950’s but wisely kept the basic structures, with Michele Olcese’s sets being formed of panels depicting scenes from Naples thus evoking the characteristic look and feel of the city. The production captured the liveliness and shabbyness of the street-life, but act one is not just about vibrant street life and processions, and Manfred Schweigkofler’s handling of the crowds enabled us to appreciate the quieter moments. He drew strong performances from his cast in all he more intimate moments. The large chorus threw themselves into the action with a will, and sang strongly. Perhaps there was a certain staidness in their manner, but this fitted in with the 1950’s setting, and the orgy was very effectively done yet firmly in period. The statue of the Madonna was a remarkable structure seemingly made of light, the design references became clear in act two when Maliella, covered with diamonds, began to resemble the twinkling brilliance of the statue.

Maliella is a big role, requiring a powerful lyric/dramatic voice. Natalia Ushakova’s repertoire stretches from Violetta through Tosca to Elsa and Salome. In the first act she brought out Maliella’s innate anger, even in the jollier moments such as her hymn to the joys of freedom, but she seemed a little careful and the rich orchestration threatened to overwhelm her. She seemed to relax somewhat in act two, in the series of powerful duets taunting Gennaro and flirting with Rafaele leading to an ecstatic duet with this latter. Natalia Ushakova seemed to throw caution to the winds and gave an incendiary account of her final scene.

Scéna

Scéna

Kyungho Kim’s Gennaro was a sober, intense young man with a neatly observed obsessive nature. Kyungho Kim’s voice had a richly powerful dark timbre allied to an heroic steadiness which brought forth a finely consistent account of the taxing role. His final scene, being castigated for sacrilege by the Camorra was as powerful as it was harmonically innovative with Wolf-Ferrari stretching tonality to breaking point. Though Gennaro’s obsessions make him a rather difficult to love character, Kyungho Kim’s performance went a long way towards eliciting our sympathy.

Daniel Čapkovič was neatly suave as the oily Rafaele, but allied to a powerful voice with a fine burnished tone. But the role need intensity and power as well as suaveness and a sense of line, and Daniel Čapkovič had the necessary reserves, but he always sang with the required seductivness so that Rafaele was attractive and dangerous, rather than boorish. Denisa Šlepkovská was a strong Carmela, warmly sympathetic of voice and monstrous in the intensity of her smothering love for Gennaro and indifference to Maliella’s will for freedom.

The numerous smaller roles were strongly taken, with lots of cameos on the first act such as Igor Pasek’s dim Biaso, Maxim Kutsenko’s charming Totonno, the Rafaele’s rather scary lieutenants Ciccillo and Rocco played by Peter Maly and Frantisek Duriac, the three girls providing lively entertainment to the Camorra played by Jana Bernathova, Maria Rychlova and Katarina Florova and many, many more.

Just as important was the orchestra, under Friedrich Haider’s strongly inspiring direction. Throughout the orchestral playing had an impressive sense of flow, with details brought out and a lovely timbre to the playing. This did not sound like an unfamiliar score, and clearly there had been a lot of preparation which paid off.

The performances are being recorded with the hope of finding a record company to issue a recording, let us hope that they are successful.

Wisely the production chose not to indulge in too many modish modernism, in such a complex and unfamiliar opera conveying the music and drama’s essential purpose was clearly a priority, and this was certainly achieved. I was in a press party, and was the only member of the group to have seen the opera before (at Opera Holland Park in 2014), and all were impressed both by the quality of the work and the performance.

The performance by SND was an immense achievement for the whole ensemble, but more than that it was a vividly, vibrant piece of musical theatre and showed that Wolf-Ferrari’s opera might yet achieve its place.

Robert Hugill

Cast and production information:

Gennaro: Kyungho Kim, Carmela: Denisa Šlepkovská, Maliella: Natalia Ushakova , Rafele: Daniel Čapkovič, Biaso: Igor Pasek, Totonno: Maxim Kutsenko, Ciccillo: Peter Maly, Rocco: Frantisek Duriac, Stella: Jana Bernathova, Concetta: Maria Rychlova Serena: Katarina Florova. Conductor: Friedrich Haider, Director: Manfred Schweigkofler Sets: Michele Olcese Costumes: Concetta Nappi. The SND Orchestra and Chorus, the Bratislava Boys Choir, the Pressburg Singers. Slovak National Theatre, Bratislava, 29 May 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Jewels_02.png image_description=Natalia Ushakova as Maliella and Ivan Ožvát as Biaso [Photo courtesy of Slovenské národné divadlo] product=yes product_title=Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari: The Jewels of the Madonna product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: Natalia Ushakova as Maliella and Ivan Ožvát as BiasoPhotos courtesy of Slovenské národné divadlo

May 30, 2015

Donizetti: Les Martyrs

Here in the UK, in recent years Opera Rara have introduced us to Belisario in the concert hall, conducted by Sir Mark Elder and subsequently released on CD along with Caterina Cornaro (conducted by David Parry). Even the touring companies have got in on the act, with English Touring Opera programming L’assedio di Calais and Il furioso all’isola di San Domingo this spring ( ETO spring tour 2015). The breadth of Donizetti’s achievement is now being recognised, matching the success which the composer realised in his day — when, mordantly, Berlioz would complain that ‘One can no longer speak of the opera houses of Paris, only of the opera houses of M. Donizetti’.

When Donizetti’s first grand opera, Les Martyrs, premiered at the Paris Opéra in April 1840 it was one of three works by Donizetti then entertaining the French capital, with La Fille du regiment playing at the Opéra-Comique and Lucia di Lammermoor keeping the seria fans happy at the Théâtre de la Renaissance. Les Martyrs was a re-working of Il Poliuto, after the latter had been rejected by the censors at the San Carlo Theatre in Naples. Spotting an opportunity to make use of his labours to fulfil a commission at the Opéra, the composer asked Eugène Scribe to expand and re-order Salvatore Cammarano’s three-act Italian libretto into a French grand opera of four acts with requisite spectacle, processional choruses and extravagant ballet.

The opera’s religious subject matter proved more of a hit with the Parisians than it had done with the blue-pencil wielding Neapolitans. The action takes place in the third century, in Mélitène, the capital of Armenia which is under Roman rule. The conflicts are both public and private. The violent tension between the two opposing factions — the fervent Christians on the one hand, and their persecutors, the tyrannical Romans on the other — is embodied more intimately by the protagonists, Polyeucte, a Roman convert to Christianity, shortly to be baptised, and his wife, Pauline, daughter of the Armenian governer, Félix, who secretly longs for her former beloved, Sévère, a Roman general feared to have perished on the battleground. Both suffer inner schisms: Polyeucte is torn between his love for his wife Pauline and that, which proves stronger, for his new God, while Pauline’s obedience to her father is tested by her loyalty to her husband and her lingering feelings for Sévère.

Even the latter faces his own dark night of the soul when, later, he has to choose between his duty to the Emperor and his love for Pauline. When he duly re-appears after his near-death — his bravery and survival celebrated by triumphal choruses and a gladiatorial display — Sévère is crowned proconsul by the Emperor for his heroic feats, and offered Armenia as a dowry for whomever he chooses as his wife. Distraught to find Pauline has married Polyeucte while he himself has been steadfastly serving the Empire, Sévère attends sacrifices in his honour at the Temple, during which Polyeucte declares his Christian faith (in order to save his fellow convert Néarque). Sévère now finds himself ordered to carry out the execution of his beloved’s new husband. Pauline, wracked by multiple allegiances, urges Polyeucte to renounce his God and acknowledge the Roman deities, but at the eleventh hour she experiences her own Damascene conversion. Despite the desperate please of Sévère and Félix, the Christian couple accept their martyrdom and the curtain falls to the entry of the lions.

Temples and palaces, vast amphitheatres, gladiatorial combat, Greek and Roman dance, with a pride of hungry lions thrown in at the close: it’s not surprising that it went down well with the Parisian grand opera crowd. The critical press was more mixed, however, and the production not quite as successful as Donizetti might have hoped. It received 18 performances but when it was revived in 1843 it closed after only two nights. In the ensuing years it resurfaced in an Italian translation, as I martiri, and then largely faded from view. Ironically, the more concise Il Poliuto, given its Naples premiere in November 1848 fared better and stayed in repertory throughout the nineteenth century.

Now we have an opportunity to compare both works, for in the same month that Glyndebourne Festival Opera have opened their 2015 season with the Italian ‘version’ of the work, Il Poliuto (Glyndebourne review), Opera Rara have issued a CD recording of Les Martyrs, having performed the opera in a concert version with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment conducted by Sir Mark Elder, at the Royal Festival Hall in November 2014 ( Opera Rara review). This recording presents the new critical edition prepared for that performance by Dr Flora Wilson of King’s College Cambridge and, as the CD booklet tells us, restores, ‘various cuts made to the score of Les Martyrs before the first performances in Paris … [allowing] us to hear several passages of music never before played in public, and to appreciate the opera in a version much close to Donizetti’s original intentions’. In the Festival Hall last November these ‘reinstatements’ included both short passages of extra recitative and arioso, as well as longer passages — for example, in the end-of-Act 1 trio with chorus and in Sévère’s Act 3 cabaletta. The ballets, which were not all heard in the concert performance, are here played in their entirety.

So, is Les Martyrs as lost master-piece? Not exactly, but in this committed, serious performance it has its thrilling moments. Sir Mark Elder’s pacing is decisive but flexible, and he gives characteristically meticulous attention to all details of orchestration and harmony. And, it’s a large orchestra: almost 50 string players are supplemented by double woodwind (stretching to a quartet of bassoons, 4 players of each brass instrument plus an off-stage complement, percussion, 2 harps — and, ophicleide.

The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, led by Matthew Truscott, play with enormous energy and verve. The reedy tones — valve-less horns and bassoons — at the opening of the overture establish a suitable air of righteous nobility, before warm bass pizzicatos and timpani repetitions inject forward movement, and before we know it the violins are scurrying and dancing with perfect synchronicity and crystal-clear incisiveness. The acceleration is seamless, as woodwind and brass interjections evolve into more assertive declamations; a spiralling bass descent takes us back to more restrained solemnity. Elder’s ability to move from intimacy to spaciousness is impressive throughout.

The recorded sound is bright and very ‘present’, perhaps a little too much so … but, it enables us to enjoy much superb instrumental playing. A wonderfully phrased clarinet solo introduces Pauline’s confessions before her mother’s tomb in Act 1, while her Act 3 meditations as she sits dreamily in her chamber are prefaced by beautifully intoned horn passages which give way to a silky flute solo, which is itself superseded by a snaky clarinet motif — a perfect musical representation of her avowals, fears and passions. The punchy precision and glossiness of the brass in the ‘Lutte des Gladiateurs’, complemented by vivacious timpani playing and taut string passagework, is stunning, and the subsequent dances, ‘Pas de deux’ and ‘Danse Militaire’, whip up a storm. There is effortless conversation between the various instrumental groups, as in the introductory bars of Polyeucte’s Act 3 aria, in which he foresees Pauline’s religious conversion: a legato prayer from the oboe, accompanied by low clarinets and punctured by a timpani bass, is transferred to the horns by way of a sinuous violin phrase.

The chorus (46 singers) are thunderously bombastic when volume and ebullience are required, as in the choral-finale to Act 3, or in Act 4 when the blood-thirsty crowd salivate over the of the sacrificial Christians who will be ripped limb from limb by the raging lions; but elsewhere they adopt a suitably restrained resonance, as in the balanced and well-blended Act 1 off-stage Chorus of Christians who witness Polyeucte’s baptism.

Michael Spyres is superb as Polyeucte, exhibiting infinite stamina, an incredibly strong chest register and an amazing top — demonstrated par excellence in the Act 3 ‘Oui, j'irai dans leurs temples!’, where his final top E pings electrifyingly before settling with consummate control down an octave; here Spyres’ elasticity and suave sound impeccably, and terrifyingly, capture the mesmerising self-belief of the zealous martyr-to-be. But, the tenor shows his awareness of the full range of bel canto gestures — not merely its show-stopping audacity — and there is subtlety and a perfectly spun pianissimo in the preceding ‘Mon seul trésor, mon bien supreme’.

The role of Pauline was one which was greatly expanded by Scribe, and Canadian soprano Joyce El-Khoury matches Spyres for passion and power, if not always for clarity and control. There is a beguiling joyful élan, though — not to mention impressive coloratura agility — to her expression of delight that ‘Sévère existe!’ in Act 2. And, El-Khoury’s Act III duet with David Kempster’s Sévère ‘Ne vois-tu pas qu’hélas! mon cœur succombe et cède à sa douleur?’ is something to savour. But, elsewhere I find Kempster’s rather wide vibrato sometimes disrupts the prevailing precision of Elder’s direction, although he copes well with the demands of the role — perhaps the most interesting dramatically — which repeatedly pushes the baritone voice high. Moreover, Kempster makes a terrific contribution to the Act 2 finale (not least because his French diction is excellent).

Brindley Sherratt roars impressively as Félix — his Act 2 aria, ‘Dieux des Romains’ has the portentous authority of a Sarastro — and he is matched for imperiousness by Clive Bailey’s Callisthènes, the priest of Jupiter who brings news of Sévère’s survival and promotion. The role of Néarque is very much that of ‘second tenor’, but Wynne Evans makes a strong contribution.

The recording is accompanied by a handsome book containing a synopsis, the libretto text in French and English, and informative articles by Flora Wilson and Jonathan Keates which establish the contemporary musical and political contexts and trace the genesis of the Les Martyrs and its relationship to Il Poliuto, lightened by plenty of anecdotes concerning the rivalries and ripostes of the day, as well as illustrations of Donizetti’s contemporaries and colour photographs of the modern-day cast and the OAE in rehearsal.

So, will Les Martyrs become an opera house staple in future? Probably not: the practical obstacles — length, scale and forces required — not to mention the general lack of character development might deter many an artistic director. And, while we’re quite used suspending disbelief in the opera house, modern audiences might find Pauline’s eleventh-hour transfiguration to be just one step too far beyond the bounds of credibility (and Donizetti doesn’t help, giving Pauline a waltz-like number which sounds far too ditzy). Then, what to do about the lions?

Elder gives us an exhilarating sound and sweeps us up in the melodramatic pell-mell. But, perhaps the more compact Il Poliuto will win the day?

Claire Seymour

Cast and other performers:

Polyeucte: Michael Spyres; Pauline: Joyce El-Khoury; Sévère: David Kempster; Félix: Brindley Sherratt; Callisthènes: Clive Bayley; Néarque: Wynne Evans. Conductor: Sir Mark Elder. Opera Rara Chorus, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. Opera Rara ORC52 [3CDs].

Click here for direct purchase from Opera Rara.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/lesmartyrs_cdcover.png image_description=Donizetti: Les Martyrs (Opera Rara ORC52 [3CDs]) product=yes product_title=Donizetti: Les Martyrs product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Opera Rara ORC52 [3CDs] price=$65.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=1740588

May 29, 2015

Il Trittico: Puccini's most underrated opera

By Rupert Christiansen [The Telegraph, 29 May 2015]

La Bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly - and oh yes, “the one with ‘Nessun dorma’ in it”, Turandot - make Puccini the world’s most popular opera composer, and one who earns ever more admiration as a musical dramatist and expressive melodist. Is there still some residual snobbery about his genius? Thirty years ago, I remember being shocked to hear William Walton confess in a television interview that in old age, he had come to love Puccini’s music even more than Verdi’s. Now I begin to sympathise.

May 22, 2015

Poliuto, Glyndebourne

It makes a powerful case for the opera, and also for Glyndebourne’s artistic vision. Poliuto isn’t standard repertoire — it’s nothing like L’elisir d’amore — but this brilliant production and performances show what a powerful work it is.

Political repression, religious intolerance and persecution are all too relevant today. Poliuto packs an emotional punch. We should heed its message

Donizetti’s source material was a play by Corneille, written two centuries previously. Polyeucte (Poliuto) was a nobleman in an outpost of the Roman Empire. The opera begins with brooding, murky music with a hushed but fervent chorus. Christians are meeting in secret. Three hundred years after the death of Christ, being a Christian was dangerous. Most early Christians were poor, an underclass inspired by the doctrine of heavenly rewards for earthly suffering. In a militaristic state like Rome, the idea that the meek might inherit the earth would have seemed dangerously subversive, tantamount to overthrowing the basic values of social order. Towering columns of what appear to be rough-hewn stone overwhelm the figures below, at once a depiction of the harsh conditions Christians faced, yet also the strength of their faith.

Igor Golovatenko as Severo and Ana María Martínez as Paolina

Igor Golovatenko as Severo and Ana María Martínez as Paolina

The opera begins with murky music suggesting shadows, and a hushed but fervent chorus. Into this darkness Poliuto (Michael Fabiano) appears. He’s a nobleman, an outsider. Is he a spy? His friend, Nearco (Emanuele D’Aguanno), is a convert. and Poliuto wants to find out why this strange new faith holds such allure. Poliuto’s troubled because he knows that his wife Paolina (Ana María Martínez) is still in love with Severo ( Igor Golovatenko), who she thought had died. Since Severo is now a Proconsul, with authority direct from Rome, this love triangle has toxic political complications. Severo’s costume suggests Mussolini, who defined Fascism. His guards resemble Mussolini’s secret police. With a wry tough sense of humour, director Mariame Clément has them smoking cigarettes.

Enrique Mazzola, a bel canto specialist, conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Last November, Mark Elder conducted Les Martyrs, the French version of Poluito which Donizetti created for Paris when Poliuto was banned in Naples. The LPO aren’t a period instrument orchestra like the Age of Enlightenment for Opera Rara, but Mazzola used that to advantage, creating an almost Verdian richness of colour from the relatively small forces of a Donizetti orchestra. Mazzola seems to inspire great enthusiasm from his players. Hopefully, we’ll hear much more of him at Glyndebourne (and in London) in the future.

Timothy Robinson as Felice and Michael Fabiano as Poliuto

Timothy Robinson as Felice and Michael Fabiano as Poliuto

Severo and Paolina snatch a few moments together. Martínez executed Paolina’s arias with such beauty that her voice seemed to shimmer. Good casting, since divine light seems to permeate this opera, despite the gruesome nature of the narrative. Donizetti gilds the vocal line with almost minimalist grace — delicately plucked strings, a single low flute, and the sound of the harp. For a moment, an image of a flowering tree is projected on the walls behind her Martínez’s voice blossoms with warmth that’s all too soon extinguished. When she and Golovatenko sing together, they’re singing love duets tinged with frustration and regret. Paolina, though, is a paragon of virtue, a concept both Roman and Christian.

Regimes that feel threatened turn to extremes. In the Temple of Jupiter, the crowds are whipped up to bloodthirsty frenzy. Some of the chorus had been singing Christians earlier, or Roman guards: interesting irony. Matthew Rose ‘s firmly focused bass created Callistene, the High Priest with great authority. With Severo wavering, and and Poliuto turning Christian, it’s up to him to hold up the foundations of the Roman Empire But Poliuto isn’t afraid of death. He believes in the resurrection: worldly concerns are no match. The purity of Michael Fabiano’s tenor rings so cleanly that Paolina is convinced that any faith that can conquer death is one worth having, even if it means leaving her father Felice (Timothy Robinson) singing from a wheelchair, to underline his inability to morally stand on his own two feet. When Poliuto and Paolina die, we don’t need to see blood and guts. Being True Believers, they’re simply transformed in a blaze of light. The designs (Julia Hansen and Bernd Purkrabek) with video projections, by fettFilm (Momme Hinrichs and Torge Möller) were extraordinarily beautiful. Gorgeous washes of colour. Sets that move as seamlessly as this, and transform with such subtlety are a thing of wonder. Like Paolina, I thought I could hear the angels sing.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Poliuto-Glyndebourne-3360.png image_description=Michael Fabiano as Poliuto [Photo by Tristram Kenton] product=yes product_title= Gaetano Donizetti : Poliuto, Glyndebourne Festival, Lewes, West Sussex, 21st May 2015 product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio product_id=Above: Michael Fabiano as PoliutoPhotos by Tristram Kenton

Carmen by ENO

Revivals can often bring productions into a different focus, and English National Opera’s current revival of Calixto Bieito’s production of Bizet’s Carmen (seen Wednesday 20 May 2015) had a new conductor, Sir Richard Armstrong, and new leads, Justina Gringyte as Carmen and Eric Cutler as Don Jose. Eric Cutler was making his ENO debut with Justina Gringyte making her role debut.

They were supported by a strong cast, with Leigh Melrose as Escamillo, Eleanor Dennis as Micaela, Graeme Danby as Zuniga, George Humphreys as Morales, Rhian Lois as Frasquita, Clare Presland as Mercedes, Geoffrey Dolton as Dancairo, Alun Rhys-Jenkins as Remendado and Toussaint Meghie as Lilas Pastia. Calixto Bieito’s production, designed by Alfons Flores (sets, realised by Kieron Docherty), and Merce Paloma (costumes), revived by Joan Anton Rechi and sung in Christopher Cowell’s English translation, is much travelled and originally dates from 1999. It sets the piece in the 1970’s in the dying days of Franco’s regime in a place which is recognisably Spain but is a grim marginal border region and lacking in the folkloric glamour we associate with the work. It is a bleak, dystopic vision which worked because of the grippingly vibrant performances which complemented the music.

Eleanor Dennis and Eric Cutler

Eleanor Dennis and Eric Cutler

Despite including a fine article by Hugh Macdonald, the programme book seemed entirely silent on the subject of the edition of the score being used. We seemed to have the standard Opera Comique version, though the spoken dialogue was cut to the bone, but it was there (I still have unhappy memories of the Sally Potter production’s complete excision of dialogue). Dialogue and its use, including melodrama, is an important factor in the work’s design.

This was a world of smugglers living in cars, bored soldiers being cruelly punished, fights, violence and sex for money. No-one was admirable, Carmen (Justina Gringyte) is clearly on the make using sex as a tool to work her way up, you were never sure when she was playing or when she was real. Don Jose (Eric Cutler) was a strong, silent giant who struggled with anger issues and was clearly not the brightest penny. Escamillo (Leigh Melrose) was more a two-bit spiv than a real super-star and very much just a local hero. It was shocking in its way, but the miraculous thing was that Calixto Bieito staged Bizet’s music just as it is. Unlike some productions, he did not falsify music or plot, he found what he wanted in Bizet’s score and made sense of the numerous little awkward moments which other directors have to finesse. It worked, because Bizet’s music became partly the character’s inner life, the vibrant colourful Spain which was more a concept than reality.

We opened with Lilas Pastia (Toussaint Meghie) in a dodgy white suit doing a cheap magic trick. He was clearly something of a pimp,and Bieito made the role both non-speaking and ubiquitous. Lilas Pastia’s bar was simply a case of drink by an open topped car for the use of the clients of his girls, Frasquita (Rhian Lois), Mercedes (Clare Presland) and Carmen. He cropped up at various times in curious places, a man with fingers in pies. Each act started with a visual gesture, Act 2 had Mercedes daughter all alone, dancing for her doll (she later pimped for her mother). Act 3, with its huge cut out bull advert, had a naked young man pretending to be a bull fighter. We never worked out if he was a real one or just pretend. Act 4 opened with Lilas Pastia organising the soldiers to dismantle the bull, ending up with him mock bull-fighting with the soldiers carrying the head of the bull.

Things got off to a good start with a tightly vibrant performance of the overture from Richard Armstrong and the orchestra. Throughout he kept the music on a tight rein, giving the melodies time but not allowing things to luxuriate too much or get flabby. This seemed to inculcate a similarly vibrant and vital performance from his singers. Singing her first Carmen, Justina Gringyte had a dark-toned mezzo-soprano voice with a vibrant, tight vibrato which she used to fine effect, and an admirably flexible top. This wasn’t a relaxed, sultry Carmen, but one who was uptight, on edge but still very sexy. Tall and slim, Justina Gringyte used her sex appeal as a weapon. The famous numbers were finely sung but not done in parentheses, they were woven into the dramatic fabric. Her English was communicative and characterful, with her accent giving her the necessary hint of otherness which Carmen needs, rather than getting in the way.

Eric Cutler was certainly a great find. He is moving into more dramatic territory (with Fidelio and Lohengrin coming up) and his Don Jose had a rugged, rough-hewn quality to it but with a vitality too. This matched the character, a tongue-tied bloke who exploded when he could not communicate. The flower song was nicely expressive and eloquent, and Eric Cutler knows how to shade off his voice at the top when needed. He and Justina Gringyte really struck sparks off each other. It helped that he is tall and well built (taller than Justina Gringyte in heels, and she is not small).

The role of Escamillo is all swagger and very little else, and here Leigh Melrose swaggered beautifully. His duet/duel with Eric Cutler’s Don Jose in Act 3 was full of wonderful posturing and thrilling music. Like most Escamillos, Leigh Melrose did not really have the bottom notes for the toreador’s song though he did well (you do wonder what type of voice the first Escamillo had). Leigh Melrose’s toreador’s costume in Act 4 did not really flatter him, but it is a look that few baritones could bring off.

Justina Gringyte and Eric Cutler

Justina Gringyte and Eric Cutler

Where, I think the production slipped was in the depiction of Micaela as a sassy but out of her depth Essex-girl type. Eleanor Dennis was convincing in her portrayal and made a touching Micaela who showed a vulnerability in the musical items. But the portrayal missed out on Micaela’s touching directness, and replaced it with a knowingness. Her duet with Eric Cutler’s Don Jose was finely done, with moments of humour, but without quite touching the heart the way it sometimes can. But Eleanor Dennis rose to fine heights in Micaela’s Act 3 solo.

The other singers were all vivid characters in the drama with their music part and parcel (with dialogue cut to a minimum we heard far less from some than is usual). Frasquita and Mercedes (Rhian Lois and Clare Presland) made two rather desperate tarts but their trio in Act 3 with Carmen was thrilling, the two girls attitudes contrasting aptly with that of Carmen, and with Justina Gringyte really making this count in her dark portrayal of Carmen. Graeme Danby made a gloriously sleazy Zuniga, with George Humphreys as a handsome moral-less Morales. Both Geoffrey Dolton and Alun Rhys-Jenkins looked their parts as Remendado and Dancairo, but he heard little from them except their musical characterful contributions.

The final act was brilliantly and economically staged. At the opening Lilas Pastia drew a huge circle on the ground, suggestive of the bull ring. For the big crowd scene, the chorus surged forward to the edge of the stage and we experienced the parade via the music and in the reflection of their intense reactions, In the final moments Eric Cutler and Justina Gringyte were alone, at the centre of the circle, for a powerful and evocative ending full of resonances.

The large chorus was on thrilling form with strong and disciplined singing throughout and some stunning moments, It wasn’t just the big crowd scenes which counted, but every little moment and they were firmly behind Richard Armstrong’s tight yet vibrant account of the score. They were joined by a large group of actors with many shirtless moments (and more), the men were generous with their physical charms. Under Richard Armstrong, the orchestra was in sterling form, giving a vital yet disciplined account of the score without a flabby moment.

I enjoyed Christopher Cowell’s imaginative yet direct translation. Cowell had found neat solutions to the stress problems caused by translating from French,and his language was demotically direct yet poetic. Diction was admirable throughout, this was one of those evenings when we hardly needed the subtitles.

Ultimately this was Richard Armstrong, Justina Gringyte and Eric Cutler’s evening, and between them they gave us some thrilling moments, in an evening of gripping drama.

Robert Hugill

Cast and production information:

Carmen: Justina Gringyte, Don Jose: Eric Cutler, Escamillo: Leigh Melrose, Micaela: Eleanor Dennis, Frasquita: Rhian Lois, Mercedes: Clare Presland, Dancairo: Geoffrey Dolton, Remendado: Alun Rhys-Jenkins, Lilas Pastia: Toussaint Mehie. Director: Calixto Bieito, Conductor: Sir Richard Armstrong, Revival director: Joan Anton Rechi, Set designer: Alfons Flores, Sets realised by: Kieron Docherty, Costume design: Merce Paloma, Lighting: Bruno Poet, Lighting revived by: Martin Doone. English National Opera at the London Coliseum, 20 May 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/12944.png image_description=Clare Presland,,Justina Gringyte and Rhian Lois [Photo © Alastair Muir] product=yes product_title=Carmen by ENO product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: Clare Presland,,Justina Gringyte and Rhian LoisPhotos © Alastair Muir

Jac van Steen in Conversation

We heard a good number of excellent performances, not least a superlativeFrau ohne Schatten from the Royal Opera and Elektra at the Proms, both, far from coincidentally, conducted by Semyon Bychkov. A fine Macbeth from Mark Elder and the LSO notwithstanding, there was not, though, so much in the way of rare, or even rarer, Strauss. For that, one would have had to travel further afield, or indeed — I should apologise for having slipped into ‘Fog over Channel: Continent Cut off’ mode — have been there in the first place. However, two eagerly anticipated treats for me this year will be Garsington Opera’s new production of Intermezzo and Die schweigsame Frau at the Munich Opera Festival, both works I shall see for the first time on stage.

Intermezzo has never fared well in this country, partly, I suspect, on account of unfounded fears concerning the speed of its dialogue. (If that be a problem, then so surely should it be in Der Rosenkavalier.) It came to Edinburgh in 1965, Glyndebourne in 1974, Buxton more recently still in 2012. Now a company that has long prided itself in Strauss performance has opted to perform it, staged by Bruno Ravella and conducted by Jac van Steen, whom I spoke to following rehearsals in East London. I began by asking why he thought the work, for which, following an initial approach to Hermann Bahr, Strauss wrote his own libretto, had been so neglected.

[Photo © Ross Cohen]

[Photo © Ross Cohen]

JvS: Let me start at the end of the answer. For me, it’s a challenge to prove that it is worth programming this opera more often. The reason I can only guess; it is not a symbolic, metaphorical opera with many layers, like those with libretti by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, which also have so much psychology, so much Freudian background. This opera with very domestic action stands, in the Strauss repertoire, pretty awkwardly. Also, if you look to the title, it isn’t a Traviata: it isn’t called Christine.

MB: Or Ariadne, Salome, Elektra, and so on…

JvS: Exactly. What happens is that in Intermezzo, he opens a new

path for conversational style in twentieth-century music, which is, in the

early ‘20s, a very courageous thing to do. In the meantime, we have heard so

many musical works that combine a play and opera that it becomes difficult to

take seriously something so trivial as a change of names [a mistaken conclusion

Christine draws from a letter written by her husband, the composer Robert

Storch] to be the cause of a great fuss in Robert’s life. But the score is so

brilliantly written that I want to convince everyone that it is worth listening

to and programming it more.

The other reason I think it is so little performed is that it is so hard, so

demanding, for everyone: all the singers have very difficult roles. The

orchestra has an even more difficult role; it plays very sophisticated themes

played against many other themes. So I try to find my way through the score to

make most of it possible to understand; meaning, we worked very hard on

understanding of the words. Not because it is in English, but because of the

conversational style Strauss asks for.

We perform it in English, not in German, but it is set in a German

parlando style, so now we have to adapt that style in translation, and

then to back to Strauss, and discover what did he want this or that theme to

sound like … so we discover that we need another word.

MB: … because it doesn’t work; it doesn’t sound as it should.

JvS: Exactly. The music is always number one.

MB: Which is interesting, given that the general idea is of a conversational piece. But then we see similar relationships in so many of the greatest opera composers when they ascribe greater importance to the poem: Wagner, Monteverdi. And there is Janáček too, who, in this case, we should think of as a contemporary.

JvS: Yes, indeed. Strauss took a lot of time over this work. For instance, he was on tour with the Staatskapelle Dresden. They had three weeks of touring in South America. If you go on tour, if I go on tour, I need a very good book and a good number of scores, because you are not there as a tourist but you have so much spare time. If you go to Buenos Aires, you have the atmosphere, but you are not a tourist; you do not go out because you know that, in the evening, you have to perform. So I imagine that he had so many creative ideas at this time. Of course, his life was composing, but at this time, his hobby was composing too, because he was there to conduct. He could ask himself: how can I make this character, how can I shape this theme? And I think that’s a special joy that composers feel. …

I’m very lucky in having a fantastic cast of singers and an excellent, thoughtful director, who is very sensitive to the text. He’s a very musical young man, who is very detailed, as detailed as Strauss is; and he makes the set and the setting so detailed that the combination of what you see and what you hear really fits together like it should, but as — let’s be honest — it does so rarely. And working every day six hours on that score must reflect a bit of the fun Richard Strauss had when he was in his hotel room in Buenos Aires. Performing a beautiful Strauss concert in the evening and then returning to write something very bright and intelligent.

MB: Also a little like the card games he so loved, which we see here in the opera. His love of skat, whose rules I’ve never been able to understand.

JvS: Yes, when we started to discuss the piece, he flew to Holland and came to my house. We had two lovely days and we said we’d play the game. I tried and it didn’t work, because it is so difficult. This is not a one-evening thing. But Bruno, he took a morning with the five card-players and explained the rules of the game. Not out of an idle desire to show off, to show how well he knew the rules, but to show the musical fun that Strauss knew in all of the biddings, the mistakes that colleagues make, all of which is in the music. They did that all morning. … What you see on stage now is the official game as Strauss wrote it out. It’s not just Figure 25: someone puts his hand down, and so on. They actually play the game. Someone loses a great deal of money, for example, and the audience will see that it means something, and that we have a lot of fun in playing the game.

MB: So it will convince?

JvS: Yes, it will convince. It’s not only performing as an actor and giving your hand because you are told to do so, you are playing the game, and during that game, you are singing your line. It’s one of the hardest scenes in the whole piece. Five people talking with each other, against each other, over each other, through each other, and as a conductor, you have to cue them all in. But as long as they do what Strauss writes, then it works.

MB: There’s a lesson there then?

JvS: Very much. There is no room for improvisation and that is the motto of the whole opera. I don’t let them improvise, and then it sounds like you and me sitting here talking about the opera, having a good conversation with music.

MB: Do you find the shortness of the scenes, their almost filmic — silent filmic — quality, followed by orchestral interludes, a difficulty?

JvS: I understand your question but I try not to see it as a problem. What I did, as a parallel to the director playing a game of skat without music, I did the opposite. I asked the singers not only to learn their own parts but … to learn the orchestral, instrumental liaisons between the parts. Sometimes just one beat, sometimes [and then he sang] a short motif, the Eternal Love theme, maybe four bars in the orchestra, to avoid this short-breathed conversational, cinematographic, cartoon-like style.

MB: … which can be a big problem.

JvS: It can be a very big problem. You then do not see the whole story. So what they do is now, the moment they stop singing [in rehearsals: the orchestra had yet to join them at this point in the rehearsal schedule], they sing in their heads the music from the orchestra. They will sing a clarinet line and carry it on until they sing once again. That helps out, so the conversational, short motif-style has a much longer line behind it. It’s all chopped up into pieces, but we try to convince by having the orchestra as a vocal part, and the vocal parts as an instrumental part. And Strauss is such a genius, that if you understand that trick, then it is all doable. Then the enormous mountain that singers initially have to climb — all this jumpy music: ‘where am I?’ — is part of something else. So long as you understand that process, it is doable. Ok, it takes a bit more time than Traviata, a bit more time than Tosca, but it is doable.

MB: What you say makes it sound a bit like Webern, where if you take notes pointillistically, in isolation, they mean nothing at all, whatever Stockhausen and certain others might have said. The moment you hear the line moving between different parts, then it’s like Mozart.

JvS: Yes, exactly. I did a lot of Webern earlier on in my career; now I seem to be asked more to do Bruckner and Mahler. But I’m convinced that you must respect the tradition — and then I’ll come back round to Strauss too — of Mahler, of Strauss, of Wagner, in Webern too, and don’t treat it as a note which is difficult to pitch, because unless you have perfect pitch, you can only work it out…

MB: … by interval…

JvS: … by interval. What I do with Strauss too is respect tradition, in that Strauss was a fantastic Kapellmeister, a fantastic conductor, so what you hear in the score is the relationship with Strauss’s role as Kapellmeister. It’s like the game of skat my director played: my assistant and I, we have tried to find the quotations that come from the repertoire of German opera houses. We come to Freischütz; we come to Forza del destino; we obviously come to Nozze di Figaro. It’s in the score; it’s a bit hidden, but it’s in the repertoire. And if you respect that tradition, respect that it is an opera composer writing a conversational piece, with the opera that he conducts in the back of his head, then you really get somewhere. It would be a fantastic quiz: to see who could pick out fifty quotations. Not five, not fifteen, but fifty! But what happened eventually, as we did this, my assistant and I — he’s a very intelligent young man, so he wanted to go further, to find another one, which I hadn’t, and so did I; I’m pretty ambitious — was, one evening, we came to a passage, and we said: ‘What is that? It’s absolutely a quotation, isn’t it?’ ‘Yes, it is. Shall I look it up?’ ‘Yes, look it up, and play it.’ ‘I can’t find it anywhere.’ And then we have walked into the trap that we are treating Richard Strauss — not Heldenleben or Also sprach Zarathustra, but Intermezzo — as a quotation. It’s archetypal, and we couldn’t think which opera it was from; suddenly we realised that it was the music in which one of the male characters talks about Christine — F minor, the key — now we think we have a quotation, but it is from the work itself. It has become part of us. … The writing is almost Mozartian. If you look at the manuscript for Nozze di Figaro, you don’t see a line to which he then added a harmony. It’s all one. That’s what Strauss does as well.

MB: And of course no one loved Mozart more than Strauss did.

JvS: And I’m sure there are more things in Nozze di Figaro — not just the motifs, the tunes that you and I can sing — to be discovered musically. I conducted the work a lot, and I made a tonal clock: I connected, as with seventeenth-century Affekt, which feeling he related to a certain tonality. Strauss is exactly the same. G minor is for her, when she’s bitchy. A-flat major is when they are in love. And it’s all the same sort of pattern as Nozze di Figaro. …

And then, of course, there is the descriptive quality. As you know, Strauss can orchestrate the opening of a door.

MB: That pictorial element: you can almost see what is happening on stage, just by hearing the score. Just as much as you can in Till Eulenspiegel or the Alpine Symphony.

JvS: In my Weimar years, I did a lot of Strauss, because he was there and everybody was very proud of Wagner, Liszt, Strauss having been in Weimar. I was the twenty-fifth Kapellmeister. And through doing that you understand the quality of the handwork, of how to write for an orchestra. He knew exactly what was good for the instruments, and what was possible, and how to go a little bit further…

MB: … to extend its capabilities just a little. The level of craftsmanship is something I always find astonishing in Strauss. He’s probably the only person who could have revised Berlioz’s treatise on orchestration.

JvS: Very true. And this opera is set for a very small orchestra. I only

know Le Bourgeois gentilhomme and Divertimento — of

courseAriadne is not so big, either — which need so small an

orchestra. Frau ohne Schatten — it needs a gigantic orchestra.

Intermezzo needs only Beethoven’s orchestra. It’s so abundant in

its instrumental writing. I’m looking forward to working with the orchestra

at Garsington, because for them, it is really tough. The London orchestras are

very good: they can play anything. So now my task is to give them the fun that

we have already had over the last four weeks. … There’s one thing that is

always very special in Garsington: they have a Mozart and Strauss accent to the

festival. I hope that the audience will not be afraid of the unknown aspect,

and that we can convince, once you are inside, that you will have a fantastic

evening: socially, Nature, the great music. …

What I would like is for the audience to feel what we did yesterday. We were

all moved, almost to tears, when Christine declared her love to Robert. She

sings six minutes of the most gorgeous music.

MB: That reconciliation is something quite special. As you were saying, the plot is trivial, but the relationship at this point doesn’t seem entirely unlike that of the Figaro Count and Countess — although responsibility is somewhat differently apportioned. It’s as if they’ve been dragged into the 1920s, have lost their titles, and have become a bourgeois couple; after all, Strauss calls the opera a ‘bürgerliche Komödie’, doesn’t he?

JvS: Very true. Everyone says that, in the opera, Strauss is giving his wife [Pauline, on whom Christine is based] a very bitchy character, but she has great love for him, and incredible respect. And, although she was a singer, she wanted very much to be a countess in life. They lived at the very height of Munich society. Strauss was a world star.

MB: That whole world of Thomas Mann…

JvS: …and Hofmannsthal, and so on. I think also of Prague, now, where I have a relationship with one of the orchestras. If you go to Prague and know that Alban Berg was there, Mahler too: they were all there: cultural centres with music of composers they loved to play every day.

MB: Mozart and Don Giovanni too.

JvS: Of course! Strauss is like that in Munich, Vienna, Dresden. All of these cities with such a rich tradition in opera. Prague had three opera houses, playing every evening.

MB: And so close to Dresden too, where this opera was first performed. One realises that when one visits, and sees the road signs, even the restaurants. Much more so than in much of the rest of Saxony, Leipzig for instance.

JvS: It’s a very interesting area. And in the 1920s, after the First World War, so alive! I love that era: I do a lot of Stravinsky, a lot of Alban Berg, a lot of Strauss.

MB: Schoenberg too?

JvS: Yes, although I’ve never done Moses. It’s very high on my list, but you need a good house that will let you do it, and I’m free on the market.

MB: The sort of work a Music Director will keep to him- or herself, then, as a statement?

JvS: Very much so. And as a guest, it is more the other repertoire.

MB: It would be wonderful to do Von heute auf morgen too, which is not entirely unlike Intermezzo with its ‘modern’, bourgeois plot. A similar dynamic, also a Zeitoper.

JvS: And the Hindemith opera, which resembles it a bit too, with a divorce situation…

MB: … Neues vom Tage.

JvS: That’s it. This conversational style has a very short history, but a very interesting one. With Pierrot lunaire, Schoenberg took Sprechstimme so far, but the 1920s offered something different, which we still know far too little.

Intermezzo at Garsington should offer a splendid opportunity for many of us to put that right.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Jac-4-kleur.png image_description=Jac van Steen [Photo by Jac Kleur] product=yes product_title=Jac van Steen in Conversation product_by=An interview by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Jac van Steen [Photo by Jac Kleur]May 21, 2015

May 19, 2015

Metropolitan Opera Stars Join Opera Las Vegas in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly

Four stars of the Metropolitan Opera will headline the Opera Las Vegas fully-staged, live orchestra production of Puccini’s tragic love story Madama Butterfly at Judy Bayley Theatre on the UNLV campus on June 12th and 14th.

Click here for additional information.

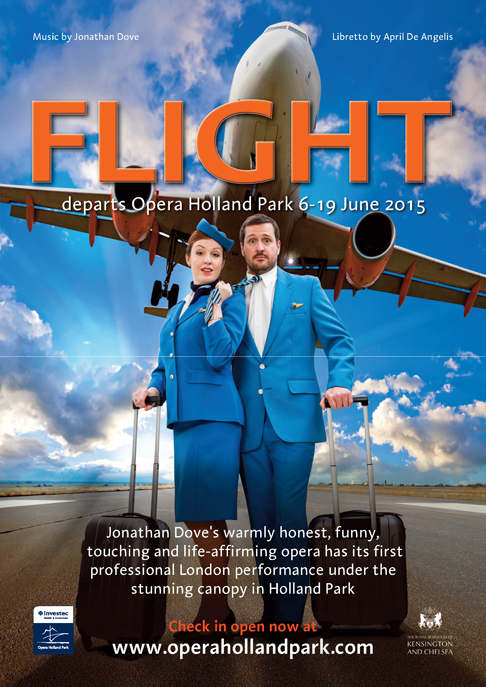

Jonathan Dove’s Flight, Opera Holland Park

Commissioned by Glyndebourne Opera and premiered in September 1998 by Glyndebourne Touring Opera, Richard Jones’ original production of Flight was subsequently staged twice in the main house, in 1999 and 2005. The opera was televised by Channel 4 in 1999, and there have since been more than 80 productions across Europe and in the US. The critical response has been near-universally euphoric.

Flight is a rarity in more ways than one. Modern-day operatic comedies are few and far between, and there can’t be many new comic operas that have received such universal acclaim since the days of Rossini and Donizetti. Moreover, how many operas are there set in an airport lounge or which feature on-stage childbirth? Yet, airports are places of transit through which pass representatives of all walks of life and in which relationships develop and unravel, and the libretto, by British playwright April de Angelis, presents an ensemble cast of 10 which serves as a microcosm of the human condition.

Glyndebourne’s General Director, Anthony Whitworth-Jones, wondered when commissioning the work whether Dove could create ‘A Marriage of Figaro for the 1990s’. Flight certainly shares Figaro’s integration of the serious and the comic. While there is much to raise a belly laugh, the Refugee’s own narrative is profoundly moving, his ‘imprisonment’ poignantly juxtaposed with the freedom of those inside the aircraft which we see take off, his life ‘on pause’ while those around him quite literally move forward.

Dove’s score is eclectic: by turns extravagantly ‘Romantic’ and restrictively ‘minimalist’, one can detect echoes from Shostakovich to Britten (not least in the word setting) to Sondheim.

Funny yet provocative, topical but also indebted to the past, Flight has become one of the most popular and oft-performed British operas of recent decades. As Fiona Maddocks, writing in the Observer commented: ‘One reason Jonathan Dove’s Flight was such a triumph at Glyndebourne is that he understands the marriage of theatre and music. He knows how to rouse passions and raise smiles. Tunes flow in abundance, and for him, creating a mood, capturing a feeling for an instant, are second nature.’

Flight will be performed at Opera Holland Park on June 6, 10, 12, 17, 19 at 7.30pm. Tickets for those under 30 years-of-age cost just £20.

Click here for an exclusive interview with Jonathan Dove .

Claire Seymour

Pacific Opera Project Presents Ariadne auf Naxos

Richard Strauss’s opera, Ariadne auf Naxos, is always a bit complicated. On May 14, 2015, Pacific Opera Project portrayed the opera’s setting as the actual opening of the Ebell Club in Highland Park, CA, in 1913. There were two contenders for the opening night’s entertainment: a newly commissioned opera, Ariadne auf Naxos, by an important new composer, and a very popular vaudeville show starring the well known entertainer, Zerbinetta. H.H. Meyer, husband of one of the club members, suggested having both shows run simultaneously. Members passed his motion so that all the indoor entertainment could conclude by 10:30 PM when technicians would set off a display of fireworks.

Pacific Opera Project, a small Los Angeles company, presented the production of the Strauss opera with an excellent group of young singers at the beginning of what should be good careers. Although the setting was 1913, the Ebell Club audience heard the 1916 edition of the opera rather than the far more difficult original version. The auditorium was set up so that the audience of two hundred sat at tables with refreshments while they watched the opera.

Sara Duchovnay as Zerbinetta with her troupe

Sara Duchovnay as Zerbinetta with her troupe

The main character in the first act was The Composer. Played by Claire Shackleton, she moved extremely well and had exemplary diction but her voice tended to be unsteady on longer notes. Dialoguing with her, Music Teacher Ryan Thorn sang with burnished bronze tones. After the intermission he and Timothy Campbell sang an amusing version of Cole Porter’s Brush Up Your Shakespeare to advertise the company’s next production: Falstaff.

Tracy Cox, the Ariadne, had a huge dramatic voice that seemed ready for a much larger space. Her sound was opulent and her top notes radiant. She did not have a great deal to sing in the first act but her glorious Act II aria, Es gibt ein Reich, was definitely worth waiting for. Her accompanying trio consisted of Maria Elena Altany, Kelci Hahn, and Sarah Beaty. Altany, the Susanna in Los Angeles Opera’s Figaro 90210, sang Naiad with honeyed tones. Hahn was an attractive Echo, and Beaty handled the low notes gracefully as Dryad. Dramatic tenor Brendan Sliger sang Bacchus, the god of wine and lover of Princess Ariadne. With powerful resonant tones and firm stagecraft, he took her from dark lamentation over the loss of Theseus into the light of new love and an eternal place in the heavens.

Brendan Sliger as Bacchus and Tracy Cox as Ariadne

Brendan Sliger as Bacchus and Tracy Cox as Ariadne

Sara Duchovnay sang Zerbinetta, the leading lady of the vaudeville company who finds herself onstage at the same time as the operatic tragedy. Duchovnay is a charismatic stage creature. Although she does not have a trill and she tossed some of the coloratura runs off rather lightly, she was a fascinating Zerbinetta. When she was onstage all eyes were upon her. Her troupe included Nicholas LaGesse as Harlequin, Jon Lee Keenan as Scaramuccio, Robert Norman as Brighella and Keith Colclough as Truffaldino. All were capable vaudevillians with the most interesting voices coming from Norman and LaGesse.

This production did not need a full sized orchestra because of the size of the hall. Christopher Fechteau’s reduction of each group to a single instrument was adequate accompaniment. Conductor Stephen Karr led his players in smart, brisk tempi while giving the singers enough leeway to create believable characters and bring out emotional expression. This production of Ariadne auf Naxos introduced an interesting young company and allowed the Los Angeles audience to hear some fine new singers.

Maria Nockin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ariadne-cox-9046-2.png

image_description=Tracy Cox as Ariadne [Photo by Martha Benedict]

product=yes

product_title=Pacific Opera Project Presents Ariadne auf Naxos

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Tracy Cox as Ariadne

Photos by Martha Benedict

May 16, 2015

Varispeed pushes the possibilities of opera forward with Robert Ashley’s Crash

According to Robert Ashley, the composer himself, “Well, if I say it’s opera, it’s opera! Who’s running this show, anyway?” The composer, who died in March of last year, was known for anecdotal libretti and “television operas” that invite close listening and that range in tone from tragic to comic to cosmically, bewilderingly existential.

Crash , the last of his operas, was performed at Roulette by Varispeed, an experimental music group consisting of a younger generation of Ashley disciples: Brian McCorkle, Dave Ruder, Gelsey Bell, Paul Pinto, Aliza Simons, and Amirtha Kidambi. First performed last year at the Whitney Biennial, Crash was reincarnated for four nights in April by director Tom Hamilton and producer Mimi Johnson. The opera is divided into six acts of fifteen minutes each, during which three of the speakers, in a Cageian fashion, take turns talking for 30 seconds each: “Thoughts” rambles, as if partaking in a phone conversation, about fourteen-year life cycles, evil short men, and the frustrations of neighbors; “Crash” swirls out a string of poetic fears and musings; “The Journal” stammers out descriptions of each year from Ashley’s life. Meanwhile, the other three voices murmur quietly in the background. The members of Varispeed rotated through the parts so that, by the sixth act, each had taken his or her turn assuming each of the voices and their varying tempos and amplifications.

Roulette TV: ROBERT ASHLEY // Crash: Act 1 from Roulette Intermedium on Vimeo.

Unlike other of Ashley’s operas, which feature loosely outlined piano or electronic parts, Crash is distinct in its accompaniment: each of the three trains of thought, which thread in and around each other like a braid of multicolored ribbons, is joined only by the quick but quiet mumbling of three other voices and an array of three different photo projections. This symphony of voices and abstract images allows the focus to fall not just on Ashley’s texts but on the spotlighted speaker and the hills and valleys of their inflections, vocal register and timbre, and unique embodiment of the “character”. So although the opera is sparse in requisites, it feels inordinately full and rich in tone as the six voices—four voices at any given moment—complement each other in continually new ways. (The interpretations of “The Journal” were most striking in their differences, as each of the members of Varispeed adopted the required stutter in a particular way.)

Despite this sense of evolution in the ever-fluctuating vocal combinations, there was an overall sensation of constancy and meditation throughout the comforting rhythms and switch-offs of the 30-second segments. Each time one of the characters started back up, no matter who was speaking, the carefully intricate yet seemingly stream-of-conscious themes and anecdotes of Ashley’s life fell into their familiar patterns. The mathematically predictable structure of the opera was the perfect framework for Ashley’s unpredictable and often humorous observations. Each of the vocalists managed to capture the ponderous, philosophical, and psychological ramblings—which in the case of “The Journal” were highly linear and easy to follow, while during “Crash” they were more obscure—with not just humor but sensitivity and musicality.

Another reason, aside from the scrupulous performance of Varispeed, that Ashley’s personal accounts and musings never felt heavy-handed or forced were the photographs by Philip Makanna, who collaborated with Ashley on the latter’s 14-hour video opera/documentary Music with Roots in the Aether. Throughout the “projection score” by Katie Cox, Eric Magnus, and Andie Springer, the abstract and peaceful visual component did not feel like a contrived, maladroit powerpoint sequence as so many new music projections do. Rather, the photographed landscapes not only depicted the American scenery so important to Ashley, but also allowed the audience to “hear the singing and the texts without the typical visual distractions”, as Ashley desired. In combination with lighting designer David Moodey’s skillful spotlight maneuvering and Kate Brehm’s stage management, the photo projections did not hammer home a message but allowed the viewers to form their own responses alongside their listening. This was the rare opera experience wherein the visual and aural experiences were united with not a blip of disjunction.

More straightforward than Ashley’s other operas, which can be oblique and convoluted in narrative and musical structure, Crash delivers a wondrous yet meditative experience. Written at the end of the sixth fourteen-year cycle of his life—and it’s surely no coincidence Ashley died just before his 84th birthday, considering his self-imposed significance on the number—the opera feels as if Ashley is looking back on his life while also looking towards the future, using the voices of young people to explore concepts of voice, story-telling, and, yes, opera.

Rebecca S. Lentjes

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ashley.png image_description=Robert Ashley product=yes product_title=Varispeed pushes the possibilities of opera forward with Robert Ashley’s Crash product_by=A review by Rebecca S. Lentjes product_id=Above: Robert AshleyRising Stars in Concert, Lyric Opera of Chicago

Excerpts performed by members of the Center had an emphasis on early nineteenth- and on twentieth-century repertoire. The Lyric Opera Orchestra was conducted by Michael Christie. Maureen Zoltek performed as the Ryan Opera Center pianist.

Among the first selections of the evening the aria “Ain’t it a pretty night” from Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah was sung by soprano Laura Wilde. Ms. Wilde’s interpretation showed excellent technique at appropriate emphatic moments. In describing the stars as they look “right down,” she placed pure high pitches on the text as a means of communion with celestial bodies. Her character’s wistful yearning “to be one of them folks myself,” who are beyond the mountains, was equally touching and led into softer passages at the close. Also from the American canon Anthony Clark Evans performed Billy Bigelow’s soliloquy from Carousel. Mr. Evans shows fine vocal projection and caused his voice to move with the rhythm of the piece, in which Billy expresses his thoughts on the news that he will become a father. The final note on “or die!” was held for an exciting end to the aria. The second act aria for soprano from Bizet’s Les pêcheurs de perles, “Me voilà seule … Comme autrefois dans la nuit sombre,” was sung by Hlengiwe Mkhwanazi. In this piece, performed as a solo less often than Leïla’s aria from the first act, Ms. Mkhwanazi observed transitions skillfully and built interest at appropriate moments, including a ravishing final trill. Jesse Donner’s performance of the lead character’s Act II aria from Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito, “Se all’impero, amici Dei,” showed not only an instinctive sense of arching line but also excellent diction throughout the aria. His use of appoggiatura as well as a polished melisma on the extended “altro cor” was impressively free of effort. The final selection in the first half of the evening was the duet for Lucrezia and Don Alfonso from Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia sung by Tracy Cantin and Richard Ollarsaba. As Lucrezia begs mercy for Gennaro, both Ms. Cantin and Mr. Ollarsaba were swept up in the emotional confrontation of this exciting duet. Cantin’s languorous variations on “Clemenza,” as she sought a hearing were rebuffed by Ollarsaba’s equally assertive “No, non posso.” When accused by Alfonso of an inappropriate attachment to the youth, Cantin’s protestations resounded on “guiro,” here and in the remaining exchange with clearly focused top notes. The concerted passage was especially effective for both singers: Ollarsaba’s accusatory “tu sei,” varied over several lines, reached impressive heights while Cantin’s decoration on the name “Borgia” proved to be every bit a spirited vocal match.

The second half of the evening began with Ms. Zoltek playing the piano part in the Eclogue for Piano and Strings by Gerald Finzi. Following this piece, a series of bel canto highlights provided consistent interest throughout the balance of the program. Two of these featured the tenor Jonathan Johnson in performances that demonstrated considerable promise. With Ms. Mkhwanazi he sang Nemorino’s part in the duet “Caro elisir, sei mio!” from Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore. Johnson has a marvelous sense of comic timing in a role to which he has clearly given considerable thought. His acting and facial expressions complemented a seamless line in the best tradition of lyrical vocalism. As Johnson’s Adina, Mkhwanazi was an impressive partner, her pointed notes and scales establishing a seductive charm for a lovelorn Nemorino. Johnson’s second offering was the florid aria for Ramiro, “Sie ritrovarla, io giuro,” from Act II of Rossini’s La cenerentola. This style of singing suits Johnson’s voice ideally, and his sense of Rossinian decoration was evident in an exciting performance. His overall approach is bright and open, top notes are secure and squarely on pitch. We can look forward to this singer assuming such a part as a featured artist in the future.

Similar reactions were garnered by Julie Miller in the excerpt “Se Romeo t’uccise un figlio … La tremenda ultrice spada” from Bellini’s I Capuleti e I Montecchi. Here the mezzo-soprano sang the Bellinian line as skillfully as the more rapid embellishments in the second part of the aria. Also by Bellini, the duet “Mira, o Norma” was performed by Laura Wilde and J’nai Bridges. Both women added sparks of color to the decorative continuity of this assured performance. Their voices remained distinctive yet contributed to a synthesis especially at those moments when they were interwoven by the vocal line.

The entire company of singers concluded a rewarding evening with the second act sextet, “Chi mi frena in tal momento?,” from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. It was an appropriate collective tribute to an evening of such promising individual as well as ensemble singing.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rising_stars.png

image_description=The Rising Stars Ensemble [Photo courtesy of Lyric Opera of Chicago]

product=yes

product_title=Rising Stars in Concert, Lyric Opera of Chicago

product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino

product_id=Above: The Rising Stars Ensemble [Photo courtesy of Lyric Opera of Chicago]

May 15, 2015

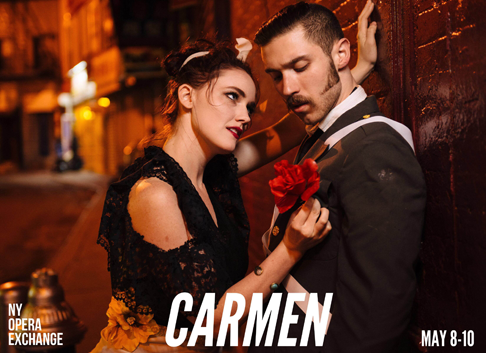

The Singers Sparkle in New York Opera Exchange’s Carmen

Audience members packed into the church hall at the Church of the Covenant on East 42nd Street to witness the spectacle of a small, emerging company taking on one of the grandest operas in the common repertory.

While not a traditional performance space, the production team managed to make this small church hall feel much like a genuine theater. Creative lighting placement added to the authenticity of the theatricality, and while the set was simple and unchanging for the duration of the opera, it was beautifully designed and offered a basic backdrop for the action of the opera. The stadium-style set suggested a metaphor oft-utilized in many previous Carmen productions — that Carmen and Jose are but two sparring members of a bullfighting ring.

Indeed, the entirety of the production existed in the realm of the traditional, taking very few liberties that might have contributed to a more creatively imagined Carmen. At the same time, the production found its strength in remaining traditional. The costuming was temporally nebulous and at times inconsistent, but in general costume designer Taylor Mills offered beautiful displays of craftsmanship, in particular with Micaela’s and Carmen’s attire. The score was well-preserved, with few cuts. This allowed for the audience to experience beautiful music often missing from productions by smaller companies, particularly the chorus numbers, which shimmered in this production, especially those sung by the female chorus.

The orchestra was on the same level as the audience, but partitioned to create a semblance of a pit. There are few things more pleasing than the opportunity to hear a full, unreduced orchestra; however, in this case, the orchestra provided proof that bigger is not always better. The orchestra, under the baton of music director Alden Gatt, grew increasingly ragged throughout the night, with some notable moments of unraveling that were obvious even to the untrained ear. Intonation and rhythmic problems were rampant throughout the night, while dynamics and musical variation were sorely underutilized. Gatt appeared at times oblivious to the breathing needs of his singers, forcing the singers into some awkward phrasing choices. There were moments of beauty, however, which hinted at the potential of this orchestra with some polishing, particularly during the overture and entr’acte.

It is to the credit of the fine group of singers that they managed as well as they did. The ensemble of singers struggled against a languid orchestra to stay on the beat, but they pulled it off admirably, especially in the jaunty smuggler’s ensemble at the close of Act II. The vocal talent was remarkable and the strongest element of NYOE’s Carmen. Avery Amereau (Carmen) has an effortlessly rich mezzo-soprano voice worthy of any professional stage in the industry, with the charisma to match. Victor Starsky’s Don Jose is terrifying and compelling, with a voice that performs vocal acrobatics with strength and beauty that remains undiminished through his final line. The scenes between Amereau and Starsky were electric like nothing else in the opera, both vocally and dramatically. The ensemble scenes sagged beneath banal and stiff staging, but vocally, each singer shone with professionalism and artistry. Of the smaller roles, Kate Farrar (Mercedes) stunned with a remarkably rich mezzo-soprano sound, while Kaley Lynn Soderquist (Micaela) soared through her high range.

Despite the kinks in this production, New York Opera Exchange is onto something, which is bringing together a community of artists, entrepreneurs, and culture-seekers. Artistic Director Justin Werner manages to infect others with his enthusiasm through sheer force of charisma and passion. Only four years old, New York Opera Exchange has serious potential to grow in excellence and artistry, and this vibrant production of Carmen suggested the beginning of this budding future.

Alexis Rodda

image=http://www.operatoday.com/IMG_0191.png image_description=Photo by Jiyang Chen product=yes product_title=The Singers Sparkle in New York Opera Exchange’s Carmen product_by=A review by Alexis Rodda product_id=Photos by Jiyang ChenMay 11, 2015

Lowering the tone

By Laura Battle [FT, 8 May 2015]

Given the enormous enthusiasm for countertenors and, increasingly, male sopranos that has flourished in recent decades, it is surprising how little attention has been paid to the female vocal range. Of course, the trend has been largely dictated by the range of available repertoire. Opera companies and period ensembles, keen to emulate the sound of 17th- and 18th-century castrati, are now spoilt for choice of high male voices. Over the same period of time, true contraltos, considered by many to mark the lower limits of the female vocal range, appear to have all but disappeared.

‘Where’er You Walk’: Handel’s Favourite Tenor

But, with their recent production of J.C. Bach’s Adriano in Siria at the Royal College of Music fresh in my mind and now this superb presentation of arias and instrumental pieces by Handel, Boyce, Arne and John Christopher Smith at the Wigmore Hall — in which Classical Opera were partnered by tenor Allan Clayton, a former Classical Opera Associate Artist — there seems little to bemoan.

The programme celebrated the 300th birthday of John Beard (1715-1791), the tenor who created more Handelian roles than any other singer of his day. Brought up in the Chapel Royal, after his debut in Il Pastor fido in 1734 Beard became Handel’s tenor of choice for the next thirty years, singing in many of the composer’s operas and oratorios. Some have made great claims for Beard, Winton Dean remarking that ‘The whole direction of the English oratorio was changed by his choice of Beard’s tenor voice for the part of Samson’, and others suggesting that his high technical ability and intelligent acting raised the profile of the tenor voice and shunted opera’s traditional ‘soprano hero’ into the side-lines.

This was a demanding programme but Clayton exhibited a relaxed demeanour throughout, somewhat diffident even. He demonstrated great stamina and diversity: as the programme led us on a chronological tour through Beard’s career, Clayton’s appealing tenor was by turns sweetly soothing, poignantly imploring and vigorously rousing. He used dynamics and registers with acute sensitivity and skill, and his quiet singing was particularly beautiful. His tenor is fairly light and climbs easily with no sense of strain, but it is flexible too and in the passages requiring virtuosic agility it had both litheness and focus. Clayton’s diction, too, was excellent.

All of these qualities were immediately apparent in the opening item, Silvio’s aria ‘Sol nel mezzo risona del core’ (The very core of my heart calls me) from Il Pastor fido. The long melodic lines of the first section were mellifluous and fluid, with octave leaps cleanly negotiated and well-judged swells of intensity, while the more vigorous passages in the central episode were precise rendered. Clayton’s open tone and easy manner conveyed perfectly the warm candidness of a young man whose heart will soon be turned from hunting hounds to seeking love. The Orchestra of Classical Opera, led superbly and with calm confidence by Matthew Truscott, provided an elegant but unobtrusive accompaniment, engaging sensitively with the voice in passages of gentle imitation.