July 31, 2015

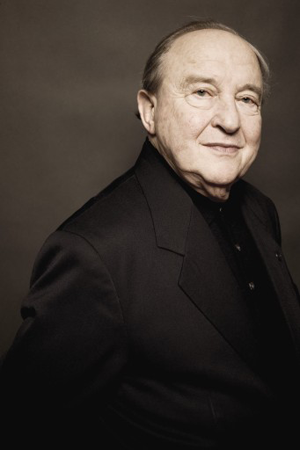

Stefano Mastrangelo — An Italian in Japan

A big man, oozing Italian warmth, he has been conducting in Japan for fourteen years, teaching in leading Japanese music schools, as well as finding time for master classes back in the Conservatorio Santa Cecilia, Rome, where he was a student in the past. He sees himself as a cultural ambassador, not just promoting Italian opera in Japan, but opening Japanese performers and audiences to a particularly Italian way of doing Italian opera.

He explains that he grew up “inside of the opera,” and has loved the medium as long as he can remember. Both his parents were opera singers. His father, the baritone Giulio Mastrangelo, travelled the world in the course of his operatic engagements; Stefano was conceived in England and has the middle name “Sydney” for his father was singing in Sydney, Australia, at the time of his birth in 1955. Many of his parents’ friends were opera people. He learned the French horn from an early age, and entered the Scala orchestra in 1977. He was drawn into conducting by Giuseppe Sinopoli, whose assistant he was for fifteen years. He remembers Sinopoli as “a very, very difficult person,” but also a huge inspiration; in his own conducting he considers himself “strongly influenced” by the older conductor and “continuing Sinopoli’s work in Japan.” Indeed he remembers Sinopoli saying that “the future of opera lay in Asia, and especially Japan.” Mastrangelo understands this to mean that not only was there a huge audience for European classical music in Japan, but a great willingness to cherish and nurture performance traditions.

Mastrangelo does indeed see the future of opera in Japan as a lot more promising than anything Europe has to offer. “Opera in Europe is finished,” he exclaims warmly at one point, before dilating at length on the problems facing the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome - problems that he feels are part of a wider cultural crisis. He is unsparing in his diagnosis of where opera in Europe has gone wrong. There has been far too much state subsidy, creating an unreal production atmosphere in which the audience was not considered to matter very much. The major European companies have bloated administrations, employing dozens of staff who may have little or nothing to do with music. And far too many productions have relied on striking, often shocking, visuals that have seldom done much to bring out the “emotional core” of the operas onto which they were expensively hitched. Mastrangelo contrasts all this nostalgically with the “simplicity” of the old impresario system that reigned in Verdi’s day. He feels that Japan has, so far, avoided most of the European mistakes.

He speaks very affectionately of the Japanese: “they have a lot of passion for opera; they want to make it their own.” At the centre of Japanese operatic life, he sees a hard core of wealthy opera lovers: people who will travel the world to see the operas they want to see, and who will invest time and money in operatic production in Japan. It was such people, he explains, whom he encountered in Italy, and who persuaded him to come to Japan in the first place. They were aware of the danger of insular standards, and wanted Mastrangelo to propagate “traditional Italian” values. To do this, he has set up what he has christened the Mirai Project, or “Future Project,” to educate singers, musicians and directors in Italian ways of doing things. The goal, he says, is to reach La Scala levels, and La Scala conveniently provides a symbol of steady progression: it is a matter of gradually ascending steps, or stairs, until Japanese performers are at the top. He sees no point in aiming at anything less.

Mastrangelo deplores the fact that German ideas about classical European music have had such a profound influence in Japan, so that Bach is considered the quintessential European genius in music in the same way Shakespeare is in literature. He feels this has led to an excessive emphasis on correctness as opposed to expressiveness; often what he calls “the heart” of the music is not brought out, or felt. He considers “creating emotion” to be central to the Italian musical ethos, and this lies at the heart of the Mirai Project. Music schools, he says, should teach literary appreciation as a matter of course. Singers need to understand exactly what they are singing, and be able to bring out not just the beauty of the words, but their particular dramatic inflection.

Getting back to Europe, I put it to Mastrangelo that though European productions may often rely too much on shock tactics, they do at least stir debate; while all the Japanese productions I have seen have presented operas as completely inoffensive classics to be savoured, above all, for their musical beauty. Should opera shock, at least a little bit? He pauses before replying, and when he talks about how opera has been shocking people for 400 years, I feel he is still trying to arrange a diplomatic answer. Finally he gets to the point: any opera should leave an audience thinking; it should seem relevant and contemporary to some extent. Behind this I catch the subtext that though Japanese directors are right to avoid shock tactics, they could attempt a bit more contemporary relevance.

Much of the opera produced in Japan relies on the enthusiastic contributions of amateur and semi-professional choruses: indeed it is the desire of such groups to be involved in opera that often sets the ball rolling, as in the “community opera” system of which Chofu is part. One of the problems with this, I suggest to Mastrangelo, is that the model massively favours operas with a big but not too tricky choral role, and in practice this usually means nineteenth-century works. He agrees with my diagnosis of the situation, but I feel he doesn’t see it as a problem as much as I do. It is a “business problem,” he maintains, slightly deflecting the question: “the Japanese don’t like taking risks.” He suggests that European opera houses are often “only half full” when modern works are staged; nevertheless, Japanese audiences could slowly learn to appreciate such works. As I understand him, he believes in a core repertoire of mostly nineteenth-century works, with Verdi at the centre, which will slowly expand as the audience for opera is built up. The closest he has come to straying outside the standard repertoire in Japan is Cimarosa’s Matrimonio segreto. He is at heart a popularist, and I detect no appetite for imposing modern works on audiences just because they have been pronounced historically significant by critics or championed by a small minority of music lovers.

I suggest that the Japanese and the British have a good deal in common when it comes to opera: they tend to think of it as an essentially foreign entity, best listened to in a foreign language. Mastrangelo strongly agrees, avoiding any comment on British opera apart from assuring me that he loves Britten, “a great composer.” “What of Japanese opera?” I go on, “should Japanese opera companies schedule more works by Japanese composers?” His answer is a surprisingly emphatic “no.” He explains that a lot of cultural familiarity with opera is needed before great operas are produced; the implication is that to Japanese composers - who, with one notable exception, only turned their efforts to opera after World War II - opera is still too foreign a genre for them to produce operas of a Verdian, international standard. They may have the technical resources, but they don’t yet have the feeling. This may be true, but I hear a lot of personal and national feeling in his answer: Mastrangelo wants a future in which Japanese audiences will go on deepening their understanding and appreciation of Italian opera in particular, and it is a future in which he sees a significant role for himself.

After the scheduled interview is over, we continue chatting about opera, and I put in a plug for Montemezzi’s L’Amore dei Tre Re as one of the most unjustly neglected operatic masterpieces. Mastrangelo warmly agrees: “Sì, sì! It is a beautiful, beautiful score! But …”

“But?”

“We could not get financial support for it in Japan.”

David Chandler

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lpict001.png image_description=Stefano Mastrangelo product=yes product_title=Stefano Mastrangelo — An Italian in Japan product_by=An interview by David Chandler product_id=Above: Stefano MastrangeloJuly 27, 2015

Proms Saturday Matinée 1

Yet I cannot help but wish that someone had shown the imagination and necessary determination to programme Boulez’s electronic masterpiece, Répons: for once, surely a work that might have been revealed to good advantage in the Royal Albert Hall. For that, one alas — as so often — has not only to go elsewhere, but abroad: be it to Paris, Amsterdam, Salzburg… (I have opted for Salzburg next month, and look forward to the Ensemble Intercontemporain under Matthias Pintscher revealing the work in the flesh to me for the first time.)

Anyway, missed opportunities aside — by the way, how about some Stockhausen? I’ve never heard a better-suited ‘RAH work’ than Cosmic Pulses — we heard a well-, often very well-performed Proms Matinée at Cadogan Hall, with no shortage of music that was either new to the country or new to the world. First up were three of Johannes Schöllhorn’s arrangements for ensemble of Notations (the piano originals, not Boulez’s extraordinary orchestral expansions). The Birmingham Contemporary Music Group under Franck Ollu sounded slightly unfocused to start with, but Notation X had a very keen rhythmic sense. La Treizième was a nice surprise: one bar from each of the twelve added together, to form another, intriguingly unified twelve-bar piece. It actually put me a little in mind of the revisiting of earlier waltzes in Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales, though perhaps I am just being a little sentimental there.I liked Schöllhorn’s sous-bois very much when I heard it at the Wigmore Hall last year; we need to hear more of him in this country. A Proms performance of a larger-scale work would be greatly appreciated another season.

Shiori Usui’s Ophiocordyceps unilateralis s.l. will surely face little competition for the foreseeable future in the world of nomenclature. We learned from a brief conversation between the composer and Tom Service that the piece is named after an infectious fungus which works its negative magic upon ants. (Whilst I remember, the printed programmes for the Saturday Matinées are, quite simply, a disgrace: not a single word on either the works or the non-Boulez composers. Can something equivalent to the evening concerts, or at least something better than that not be managed?) In five very short movements — ‘Camponotus leonarci’, ‘Spores’, ‘Pathology’, ‘The Grip’, and ‘Hyphae’ — we heard a considerable array of ensemble colour, very different in each case. There was perhaps a sense of Boulezian éclat, albeit more overtly, or at least conventionally, thematic, and also sometimes more tonal in language. It was elevating to see one newspaper critic rise from his seat and leave after that performance; it will be interesting to see whether his review covers the rest of the concert.

Betsy Jolas is but a year younger than Boulez. We seem to hear her music very little in this country; the United Kingdom premiere of Wanderlied was therefore especially welcome. Wanderlied was inspired by the idea of an old woman (the cello) travelling from town to town as storyteller, the tile borrowed from a 1943 poem by Jolas’s father. Crowds gather around the woman and comment, but two people in the crowd do not like her, yet continue to follow. What emerged was a long-breathed, humorous piece, assure both of craft and emotional expression, timbre not surprisingly an important connecting force between the two, insofar — a big ‘insofar’ — as they may be separated. I thought of it as, in a way, a song without words, or perhaps better a cantata without words. Jolas looked, by the way, almost incredibly sprightly on stage, so we have every reason to hear a good deal more from her, programming permitting.

I wish I could be so enthusiastic, or indeed at all enthusiastic, about Joanna Lee’s Hammer of Solitude. The idea fits, clearly a reference to Le Marteau sans maître — and the participation of Hilary Summers fitted too. Summers proved her usual self, that most individual of voices as communicative with words and notes as one could ask for. Alas, the three movements — ‘The hammer alone in the house’, ‘A presentiment’, and ‘A suicide’ — seem strangely childish, which is not to say childlike, in construction and expression. Word-painting is obsessive, yet basic, almost as if following a guide in a compositional exercise. The (very) sub-Berberian noises at the opening hint at a greater ambition, which yet remains unrealised. The final line: ‘Release complete, relief’. Quite.

Finally, Dérive 2. It is the Boulez work I still find the most difficult to come to grips with; I cannot claim to ‘understand’ it and indeed find it almost disconcertingly ‘pleasant’ in its progress. Boulez’s constructivism, albeit a flowing constructivism, came across clearly and, crucially, with structural as well as expressive meaning. The ghost of Messiaen seemed intriguingly to hover, or rather to fly, at times, not least in some of those gloriously splashy piano chords. The ‘lead’ taken by different instruments at different times was, perhaps, more than usually apparent, suggesting almost an updated sinfonia concertante, whereas, for instance, Daniel Barenboim’s performances (seehere and here; number three will come in Salzburg next month) have emerged, at least to my ears, as more orchestrally conceived. As is the way with even half-decent performances of such music, I noticed things I had never heard before. Something that especially struck me on this occasion was the timbral similarity — surely testament to Boulez’s work as conductor — to a passage in The Rite of Spring. I shall have to look at the scores to find where and when, or perhaps I shall never re-discover what my ears were telling me on that occasion. Such is a good part of the mystery and the magic of live performance.

Mark Berry

Programme and performers:

Boulez, arr. Johannes Schöllhorn — Notations II, XI, X (1945, arr. 2011, United Kingdom premiere); Schöllhorn — La Treizième (2011, United Kingdom premiere); Shiori Usui — Ophiocordyceps unilateralis s.l. (2015, world premiere); Betsy Jolas — Wanderlied (2003, United Kingdom premiere); Joanna Lee — Hammer of Solitude (2015, BBC commission, world premiere); Boulez — Dérive 2 (1988-2006, rev.2009).

Ulrich Heinen (cello)/Hilary Summers (contralto)/Birmingham Contemporary Music Group /Franck Ollu (conductor). Cadogan Hall, London, Saturday 25 July 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Pierre-Boulez.png image_description=Pierre Boulez product=yes product_title=Proms Saturday Matinée 1 product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Pierre BoulezThe Maid of Pskov (Pskovityanka) , St. Petersburg

At 11 a.m. on a Monday morning three priests sang a mass for a dozen elderly women and one man, all dressed in traditional peasant costume. As is Russian Orthodox custom, they stood at seemingly random spots on the stone floor. To complete the Dostoyevskian scene, one mentally challenged man sat in the corner rocking and mumbling to himself. As I slipped in, a priest turned to face an altar of icons and began to sing the liturgy. In that space, his deep bass rang forth smoother, warmer and more resonant than anything I have heard on an opera stage in several decades. After a few minutes, he signaled to the congregation, which joined him in perfect four-part harmony. The visceral power of full-throated human voices singing a capella rooted me to the spot, transfixed.

The music I heard that morning lies at the heart of the tradition of Russian epic opera, with its massive choruses, giant bells, grand bass roles and sweeping themes of sacrifice, guilt and redemption. Of such works, Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina are most commonly performed in the West, but the same tradition spawned an opera I had heard the night before at White Nights, Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Maid of Pskov (Pskovityanka, also known as Ivan the Terrible). Rimsky-Korsakov composed it alongside his roommate Mussorgsky, who was working on Boris at the time. It tells the story, well-known to Russians, of how the ancient town of Pskov lost its freedom to Tsar Ivan IV Vasilyevich in the 1500s. It recounts the death of a young maiden, Ivan’s lost daughter, who is caught between her lover, a diehard defender of ancient liberties, and her father the Tsar. The opera is a modest national treasure almost never performed outside of Russia.

Viktor Lutsyuk as Mikhail Andreyevich Tucha, Tatiana Pavlovskaya as Princess Olga Yurievna Tokmakova

Viktor Lutsyuk as Mikhail Andreyevich Tucha, Tatiana Pavlovskaya as Princess Olga Yurievna Tokmakova

The opera calls for a bass with great vocal and dramatic charisma to sing Ivan the Terrible. The Tsar’s initial scene, for example, contains mostly sung recitative of constantly changing moods: a sarcastic aside is followed by an imperious command, a sudden moment of tenderness, a request for food, and an expression of world-weariness. Fyodor Chaliapin, whose self-portrait still hangs on the wall of a practice room at the Mariinsky, was legendary in the part. Though we have no recording, one can imagine how he must have savored its theatrical potential, turning on a kopeck to inflect each line differently, and projecting it to the back row of this very same hall.

Yet where have the great Russian basses gone? Consider Alexander Morozov, who sang the role as I heard it performed on 5 July. Not only is he no Chaliapin (who is?); he does not even possess a basic instrument in the same league as that of Vasily Gorshkov, who sang the Boyar Matuta with fluency, feeling and reasonable fullness of sound. A Tsar Ivan the Terrible who cannot vocally overpower a local boyar of Pskov not only sucks the life out the musical score, but makes nonsense of the dramatic proceedings. At times Morosov was completely inaudible from the ninth row over modest orchestral forces, and in the final scene he gave up, bawling and hamming instead.

Mariinsky insiders told me that Morozov was second-best, though his name was on the cast list from the start. (Perhaps Alexei Tanovitski would have been preferable, despite rumors of recent vocal troubles.) Music Director Valery Gergiev did cancel, which is a widespread problem in St. Petersburg. In La Traviata, for example, superstar Anna Netrebko was replaced as Violetta by the darkly passionate but uneven young Oxana Shilova, evidently taking with her Latvian tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko and again Music Director Gergiev. Is the economic crisis is sapping internationally active artists from the festival? Until this is sorted out, those contemplating a trip to the (so-called) Stars of the White Nights should beware!

Yet the problem of basses is clearly more fundamental. Many Russian opera administrators voice deep concern about the lack of basses up to the standards of their illustrious predecessors. Even if we leave Chaliapin out of it, one can track that decline in the role of Ivan the Terrible from the standard a half century ago (Aleksandr Pirogov in the 1947 Bolshoi recording of this opera and Boris Christoff in live recordings from the 1950s and 1960s) to what has been on offer more recently (Vladamir Ognovenko’s solid portrayal in Gergiev’s 1994 recording and the basses mentioned above). A chasm has opened up between what one hears in Orthodox churches and what one hears on a Russian opera stage. Until it is closed, it will be difficult to do full justice to this vital repertoire.

Alexei Tanovitski as Tsar Ivan Vasilievich, Varvara Solovyova as Boyarinya Stepanida Matuta (Styosha)

Alexei Tanovitski as Tsar Ivan Vasilievich, Varvara Solovyova as Boyarinya Stepanida Matuta (Styosha)

Despite the gaping vocal hole at its core, the Mariinsky production was most other respects enjoyable. Best of all was the old theater itself (so-called Mariinsky 1), which dates from 1860. It is not only lovely to behold, with gilded gold, straight-backed chairs and a pale blue-green painted ceiling. It is also—to judge from what we heard from Row 9—one of the most acoustically live and well-balanced opera houses in the world, with full, immediate and pin-point directional sound. The visceral experience of opera there bears no resemblance to brassy yet distant impact of opera in big halls like the Met and the Bastille (or even the newly opened Mariinsky 2), or even the somewhat less immediate impact of opera in other great houses, such as the Wiener Staatsoper or Covent Garden. While the orchestra under the young Finn Kalle Kuusava was sloppy at times, certainly lacking the punch Gergiev gives such works or the romantic sweep imparted by Simon Sakharov fifty years ago, it sounded vital in the hall.

The Mariinsky Maid of Pskov is a Fyodor Fedorovsky production dating from 1952 (refurbished by Yuri Laptev in 2008) and its staging of the cities and landscapes of old Russia reminds us how much color, romance, grandeur and realism traditional painted flats can offer. Diehard advocates of Regietheater would have been bored by the straightforward, almost fairy-tale, nostalgia, but the approach seemed to me just right for this excursion into medieval life. Moreover, flat and closed sets reflect sound well, adding to the hall’s acoustical glow.

Aside from Morosov’s weak and Gorshkov’s strong showing, the singers acquitted themselves competently. Maxim Aksenov possesses a strong, somewhat metallic tenor, with a more burnished tone at the top than the bottom—the right kind of voice for Mikhail Andreyevich Tucha, the romantic young defender of a city doomed to servitude. Soprano Svetlana Aksenovа, who sang Princess Olga Yurievna Tokmakova (the maid of Pskov), sang in the modern way: evenly, correctly, well-projected, slightly pushed, with a bit of Slavic steel in the voice, and without a great deal of feeling or character. Veteran mezzo Lyudmila Kanunnikova used a large voice and idiomatic style to advantage in her Act One cameo as the wet-nurse. The other princes, boyers and officials, notably Yuri Vorobiev, as well as the chorus, sang with virility. While none of this could be mistaken for the top-flight vocalism that can be heard at Glyndebourne, Salzburg or other top-tier summer festivals in Europe, the whole was more than the sum of the parts, due to the fine acoustic, superb diction, idiomatic delivery, and the sense that singers were performing a well-known work from their distinct tradition that could only be heard here.

The sense of being at a distinctively Russian occasion was reinforced by the audience—a crowd for which those who seek to expand the appeal of opera (think Peter Gelb and his PR minions at New York’s Metropolitan) could only wish. This Sunday-night performance was all but sold out, and the audience contained quite a number of common people of various ages, including numerous families with children. Listening to a tale from their own history, they—even an older gentleman next to us who smelled strongly of vodka—were well-behaved, attentive and responsive. The clear impression is that, from the perspective of audiences, Russian opera remains vital in the country of its origin. Now all we need are some great basses.

Andrew Moravcsik

Cast and production information:

Tsar Ivan Vasil’yevich (The Terrible): Alexander Morozov; Prince Yuri Ivanovich Tokmakov: Yuri Vorobiev; Boyar Nikita Matuta: Vasily Gorshkov; Prince Afanasy Vyazemsky: Mikhail Kolelishvili; Mikhail Andreyevich Tucha: Maxim Aksenov; Yushko Velebin: Alexander Nikitin; Princess Olga Yur’yevna Tokmakova: Svetlana Aksenovа; Boyarinya Stepanida Matuta: Varvara Solovyova; Vlasyevna: Lyudmila Kanunnikova; Perfilyevna: Svetlana Volkova; Malyuta Skutatov: Gennadt Borchenko; A Watchman’s Voice: Denis Begansky. Revival of the 1952 Production with sets and costumes by Fyodor Fedorovsky. Revival Stage Director: Yuri Laptev. Conductor: Kalle Kuusava. Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg, Russia (5 July 2015).

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Maid_10.png image_description=Alexei Tanovitski as Tsar Ivan Vasilievich, Tatiana Pavlovskaya as Princess Olga Yurievna Tokmakova [Photos courtesy of Mariinsky Theatre] product=yes product_title=The Maid of Pskov (Pskovityanka) , St. Petersburg product_by=A review by Andrew Moravcsik product_id=Above: Alexei Tanovitski as Tsar Ivan Vasilievich, Tatiana Pavlovskaya as Princess Olga Yurievna Tokmakova [Photos courtesy of Mariinsky Theatre]Prom 11 — Grange Park Opera: Fiddler on the Roof

Perhaps this was a sign that I was in for an unusual evening: after all, it was Grange Park Opera’s first appearance at the Proms and the first time that Fiddler on the Roof — the 1964 Broadway hit by Jerry Bock (music) and Sheldon Harnick (lyrics), based on Yiddish tales by Sholem Aleichem — had been performed at the Proms. To add to the novelty, there was the casting of Welsh bass-baritone Bryn Terfel as the deep-thinking Russian dairyman, Tevye, who struggles to maintain his Jewish cultural traditions in the face of his daughters’ wishes to marry for love and the Tsar’s efforts to expel the Jews from the Anatevka shtetl in 1905.

But, then again, diversity of genres has become a staple feature of the Proms scheduling over recent years: European dance music, a ‘grime symphony’, Bollywood and bhangra music all feature this year. Moreover, opera companies are increasingly turning their attention to ‘popular’ repertoire which, one presumes, they hope will fill seats and win new audiences for opera (whether they are right or not is open to debate). Thus, Opera North will follow this season’s Carousel with Kiss Me Kate in 2015-16; at Welsh National Opera Sweeney Todd is scheduled for the autumn, hot on the heels of this summer’s production of Sondheim’s musical thriller at ENO. In the case of Grange Park Opera, they tested the waters ten or so years ago with productions of Anything Goes, Wonderful Town and South Pacific. This year, the opportunity to see a ‘star’ of Terfel’s calibre and renown may have tempted some of those who travelled to bucolic Hampshire in June to see director/designer Antony McDonald’s production of Fiddler at The Grange. Terfel’s certainly not new to the genre having shown his musical theatre calibre as the Demon Barber in several productions since 2007. So, maybe this was ‘first’ was simply a sign of the times rather than a revolution.

I’ll get my major criticism out of the way first. Not surprisingly, and perhaps necessarily, the performance was amplified; but, either the engineers seriously misjudged the volume level or the singers’ unfamiliarity with the venue led them to fear inaudibility, because the amplification was simply too loud. Ear-splittingly so at the start. I assume adjustments were made, or perhaps the singers adapted — because things did improve and were markedly better after the interval.

Terfel himself must take some of the blame. In contrast to his fellow performers with their light-weight music theatre voices, his Wagnerian bass-baritone can undoubtedly swell to the far reaches of the vast auditorium unassisted Yet, he boomed the opening dialogue, completely obliterating the solo Fiddler perched in the organ loft (a somewhat dishevelled and melancholy Houcheng Kian, who played suavely and linked the scenes effectively, but who, except when he was front of stage, might have benefited from some magnification himself), and encouraging the chorus members to strive to match his thunder. It would have been an exciting opening but for the painful rattling of my ear-drums. Perhaps if I was a habitual rave or gig attendee I’d have had no objection. Fortunately, things did improve but throughout the performance spoken text in particular was frequently yelled, sometimes at the expense of emotional intimacy between the characters on stage.

With that complaint out of the way, I should say that this was an absorbing and highly entertaining evening, one in which Terfel perhaps inevitably outshone his fellow cast members vocally, although there were some strong performances. Dressed in his milkman’s apron, lamenting the changes that were sweeping away heritage and homeland, but relishing a wedding knees-up, Terfel looked utterly at home in the role. The sung text was crystal clear, with a relaxed sense of rhythmic give-and-take which showed a natural feeling for the idiom.

Reviewing Terfel’s first essay as Dulcamara in the revival of Laurent Pelly’s production of Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore at the ROH last November, I expressed admiration for his comic judgement and pacing. I had feared that he would over-egg the sleaze and slap-stick but the bass-baritone showed discernment and imagination: his Dulcamara had seemed to be a ruthless conman with little care for his victims or his own personal hygiene but later revealed himself as a mischievous charmer with twinkling charisma. It was a winning transformation. Here, too, Terfel balanced worldly authority with familial warmth: his temper may have been quick to spark but it was just as readily tempered by love and reflection.

The big numbers all come early in the show. ‘If I were a rich man’ may have been a trifle stentorian in places — as Terfel stood like an imperious Wotan, each foot atop a milk churn — but he used his voice intelligently and during the evening conveyed touching, diverse emotions. And, there were more intimate moments, as in his lovely duet, ‘Do you love me?’ with Janet Fullerlove’s Golde; although there was some vocal mismatch in terms of timbre and projection, there was convincing feeling, and Fullerlove demonstrated her neat comic timing, deftly and wryly denying he husband a kiss in the song’s final moments.

Charlotte Harwood was a characterful Tzeitel, Tevye’s eldest daughter, and her scenes with Anthony Flaum’s Motel, the tailor who convinces Tevye to give both his blessing and his permission to their marriage, were touching. Flaum’s strong singing and responsive acting made him an appealing presence. Katie Hall sang Hodel’s ‘Far From the Home I Love’ sweetly and without affectation, abandoning the nasal twang and exaggerated American accent which had marred some of her earlier numbers (exacerbated by the miking — and, she was not alone in this regard); as her beloved, Simon Pollard was a dynamic Perchik. The more tentative sentiments of Molly Lynch (Chava) and Craig Fletcher (Fyedka) complemented the older pairings nicely. Rebecca Wheatley was the busybody matchmaker Yente, with a tendency to shriek her dialogue; Cameron Blakely proved nimble of voice and footwork as the butcher, Lazar Wolf, who believes he has won his dream bride only to be denied by Tevye in the face of Tzeitel’s sincere entreaty

Much of the driving momentum of the work comes from its wonderful ensemble set-pieces. The GPO Chorus sang with gusto and mastered the complex, inventive choreography (Lucy Burge) with aplomb. Even more impressive were the Cossack-leaps, bottle-balancing routines and wild whirlings of the dancers. The BBC Concert Orchestra, seated behind the performers, gave a sparkling reading of the score. They seemed to be having fun rendering the rich orchestrations, guided by nimble direction from conductor David Charles Abell.

The semi-staging was simple but serviceable — a few tables on wheels, assorted chairs and beds, and a fine chuppah for the matrimonial ceremony. The musical is somewhat imbalanced: the best-known numbers and the most up-beat ensembles are clustered into the long first part, with the emotional barometer swinging from festive to forlorn after the interval, as Tevye and his community face a battle for survive at home or uncertainty in the ‘promised land’ of America. It’s probably not the fault of McDonald, stage director Peter Relton, or the performers that the ending felt somewhat rushed, with the pathos of the uncertain ending not fully conveyed.

Though Terfel received a rapturous reception at the curtain call, he seemed keen to insist this was an ensemble performance, taking his place among the ranks despite the Prommers’ wish to laud his individual triumph. But, at the final reckoning it was Terfel’s vocal expertise and allure, and his stage magnetism, which made this such a heart-warming evening.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Tevye: Bryn Terfel, Golde: Janet Fullerlove, Tzeitel: Charlotte Harwood, Hodel: Katie Hall, Chava: Molly Lynch, Yente: Rebecca Wheatley, Motel: Anthony Flaum, Perchik: Jordan Pollard, Lazar Wolf: Cameron Blakely, Constable: Mark Heenehan, Fyedka: Craig Fletcher, Fiddler: Houcheng Kian; Conductor: David Charles Abell, Stage director: Peter Relton (based on the production by Antony McDonald), Choreographer: Lucy Burge, Costume designer, Gabrelle Dalton, BBC Concert Orchestra, Grange Park Opera Chorus. BBC Proms, Royal Albert Hall, London, Saturday 25th July 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/GPO_FiddlerOnTheRoof_2015_Robert_Workman_001.png image_description=Bryn Terfel as Tevye [Photo © Robert Workman] product=yes product_title=Prom 11 — Grange Park Opera: Fiddler on the Roof product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Bryn Terfel as TevyePhotos © Robert Workman

July 24, 2015

Saul, Glyndebourne

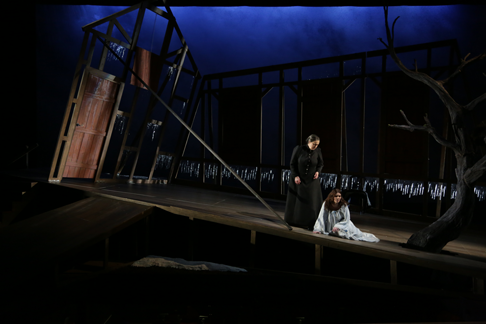

Barrie Kosky‘s much anticipated new production of Handel’s Saul opened at the Glyndebourne Festival on 23 July 2015, Kosky’s debut at the house and their first production of Saul. Though not an opera and never intended for the stage, Handel’s oratorio Saul is one of his most dramatic works and Kosky created from it a remarkable piece of theatre. A strong cast was led byChristopher Purves as Saul, andIestyn Davies as David, withLucy Crowe as Merab,Sophie Bevan as Michal,Paul Appleby as Jonathan, John Graham-Hall as the Witch of Endor and Benjamin Hulett as Abner, High Priest and Amalekite.Ivor Bolton directed the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment from the harpsichord. Designs were by Katrin Lea Tag, with choreography by Otto Pichler, and lighting by Joachim Klein.

Handel’s oratorio Saul was premiered in London in 1739. It has a libretto by Charles Jennens, who not only wrote the libretto for Messiah but was responsible for some of Handel’s most remarkable dramatic oratorios. The piece was intended as theatre of the mind, though premiered in the theatre it was performed in concert but Handel’s scores include stage directions clearly indicating the way his mind worked in these circumstances. What a piece like Saul gave him was a sense of real narrative clarity, this was a story everyone knew and which had a clear development from beginning, middle to end, very different from the convoluted scene based drama of the opera seria, where it was the effect of individual scenes which mattered rather than the (sometimes ludicrous) progression from scene to scene. Handel’s response was a dramatic meditation on the story, sometimes action proceeds at lightening pace (in the Glyndebourne programme book Barrie Kosky talks of the way, freed from da capo arias, Handel sometimes write music of extraordinary concision), but then there will be a long chorus when the action is frozen and the chorus almost steps out of the drama to consider it, and talk about it to us.

This gives the director remarkable freedom, there is a lack of specificity about the dramaturgy which can be filled in many ways. Of course, there are problems; you have to find something to do during the long choruses with all those singers on stage, and something which has a dramatic coherence and does not look like decoration merely added in. In 2012 I saw two very different stagings of Handel’s Jephtha (Frederic Wake Walker’s at the Buxton Festival, and Katie Mitchell’s at WNO) which showed quite how responses to the drama could vary.

Benjamin Hulett as the High Priest

Benjamin Hulett as the High Priest

If I say that Barrie Kosky had clearly listened to Handel’s music and created a piece of theatre based on it, then that is intended as a great compliment as too often I get the impression that directors stage the libretto rather than the musical drama. Kosky, designer Katrin Lea Tag and choreographer Otto Pichler created a semi-abstract, coherently thought through response to the music. Kosky and Ivor Bolton drew some remarkable performances from the singers and players. One of the themes that Kosky identified in the piece, which his staging brought out strongly, was the King Lear like resonances with a King who goes mad, and two warring daughters. Kosky had increased these resonances by conflating the small roles of Abner, the High Priest and the Amalekite into a single fool-like role.

I say advisedly that this was a remarkable piece of theatre because though Handel’s score was at the very core of the piece, Kosky had added two elements to it which gave the staging some of its specificity (and added the Marmite element too, you either loved or hated it with little in between).

First the sound, the whole piece had an extra aural sound-track ranging from the whoops and cries of the chorus, through the communal thumpings, bangings and shoutings, to the shouted extra dialogue and Saul’s ravings. Some of this was a response to the drama going on in counter-point to the music, for instance when Saul presented Merab to David she was furious and Saul and Merab had an encounter which, not in the score, was performed in dumb-show but with the odd sound which intruded on the music. Also, there were many moments when you felt that Kosky did not find Handel’s music quite enough, and needed to add something. The results added up to an extra aural component which was present enough for me to find unsatisfactory and disturbing. If you listen to a radio broadcast of the performance then you are likely to find it slightly strange at times.

Sophie Bevan as Michal and Iestyn Davies as David

Sophie Bevan as Michal and Iestyn Davies as David

The second element was visual, dance played a large part in the whole performance. There were six dancers who made a strong element to the overall drama. But Otto Pichler’s choreography extended to the singers too so that whatever you thought of his visual language, he and Kosky had folded movement into the whole ensemble rather than just adding a couple of dancers for window dressing. Like everything else in the production, this was the result of strong, thoughtful decisions which I appreciated. Unfortunately, I did not respond to Otto Pichler’s visual vocabulary and found the dance element neither expressive nor stimulating, feeling that his perky, energetic choreography rather trivialised the music.

The evening opened with a series of visual coups. First the overture was played with the curtain down, with just a huge bloody head of Goliath visible, definitely a big plus point. Then as the curtain opened we saw Iestyn Davies as David, stripped to the waist, bloodied and clearly traumatised, then suddenly the rear curtain rose to reveal a huge table set for a feast (like the 16th century Dutch still life printed in the programme book), on which the chorus was sitting and standing. For the opening sequence the chorus moved, in stylised way on this table and then the ensemble developed with the dancers coming on. Costumes were neo-baroque, creating an exotic, slightly a-historical feel and in the huge wigs and overdone white make-up, creating a sense of parody too.

The whole piece took place in this space, with it plain walls and the floor of artificial earth (clearly this season’s must-have for directors, following on from Covent Garden’s recent production of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell). The dinner interval was after the Act Two duet for David and Michal (O fairest of ten thousand fair) and its subsequent chorus. The second half opened the symphony and formed a clear divide with the second part as the dark part, opening in darkness with a field of candles and with the performers now dressed in black.

Christopher Purves as Saul and Lucy Crowe as Merab

Christopher Purves as Saul and Lucy Crowe as Merab

Though the visual language for the production was strong and pervasive, and at times I found it to be hyper-active, Kosky was responding to the music and when demanded gave us simplicity. David’s singing of his aria to sooth Saul, and then quietly cradling him whilst the harp played, or the Dead March performed with a stage strewn with bodies but no other accompanying action. And whatever you thought about the visual language, Kosky drew some truly remarkable performances from his cast.

Christopher Purves’ account of the title role was truly Lear-like, as he depicted Saul’s complete descent into madness. The occasional mad episodes in the first part turning into complete ravings in the second. It was a truly fearsome and mesmerising performance, and Purves was gripping in his singing of Handel’s music (Saul hardly gets a proper aria, the role is almost all recitative and arioso). But the performance came at some cost to the music, as Purves created the sense of madness by distorting the vocal line (thankfully only occasionally), and by adding extra spoken contributions to create intense theatre.

Iestyn Davies as David was slightly cool, calm and unreadable. He started with David traumatised and shell shocked, and there was a sense in which the character took most of the piece to recover from the opening drama with Goliath. This was counter-parted by the cool beauty of Davies’ singing and his account of O King, whose mercies are numberless was one of the highlights of the evening. But David’s character is also puzzling because of the dramaturgy of the piece, as he develops strong relationships with both Jonathan and with Michal. Kosky’s production gave a clear sexual element to the relationship with Jonathan (with the two in a steamy clinch at one point), but offered little in the way of explanation except to suggest that David was an opportunist schemer. But the beauty and intelligence of Iestyn Davies performance helped to bring the role alive in multiple ways.

Lucy Crowe made Merab a far more interesting character than can sometimes happen, and Crowe’s plangent tones, thrilling and beautiful yet extremely calculated, meant that even when at her most vicious we responded to Merab in a way. The bleached plangency and technical perfection of Crowe’s performance of Merab’s music ensured that the contrast with the two sisters was played up as Sophie Bevan’s Michal was all bubbly, running-around excitement. From the first moment Bevan set eyes on Davies, it was clear that Michal was obsessed with David and Bevan really brought this over. She was a complete delight in the arias, bringing a real sense of charm.

The young American lyric tenor, Paul Appleby was new to me. He brought a strong sense of interior drama to Jonathan, he too was very taken with Iestyn Davies’ David from the first moment and their relationship was developed and played out very clearly. In that sense he made a fine component to the drama, but Jonathan is perhaps an underwritten role and Appleby did not manage to make the music really count. He sang effectively, but without the specificity of the other performers and I have to confess that I found his phrasing a bit lumpy at times.

Benjamin Hulett was truly brilliant as the new fool-like character, welding his sequence of almost random arias into a clear role and having an omnipresent theatrical effect which gave a strong counterpoint to the drama. We never did work out why he was given artificially large bare feet (we have to assume that Hulett’s real toes are not that size!), perhaps to give a sense that this is a Pan-like observer and commentator. His interventions, and arias sung to the audience brought a real feel of extra commentary to the drama and his music performance was spot on and certainly showed him ready to take on larger roles.

Thankfully the role of the Witch of Endor was cast with a man, as it should be, and John Graham-Hall brought a wealth of experience to the role. Kosky seems to have seen the scene in Lear-like blasted heath terms. By now Christopher Purves’ Saul was stripped to his boxer shorts and John Graham-Hall’s witch appeared out of the ground and was an old crone also stripped to the waist with huge pendulous breasts on which Saul sucked, and the voice of Samuel spoke through Saul so that Purves sang both roles. It created an incredible piece of theatre from what is one of the strongest scenes in the oratorio.

The hard working chorus was amazing, singing Handel’s taxing, large-scale choruses with both strength and expressiveness. For the more serious ones, such as the big jealously on, their range of movement was restricted as Kosky clearly wanted us to concentrate on the music and there was a great deal to enjoy. For the livelier choruses in Act One we were treated to the sight of them dancing and singing, and this did on occasion cause some instability in the ensemble, but overall this was a powerful, strongly sung account of one of Handel’s finest oratorio choruses. Daniel Shelvey from the chorus took the small role of Doeg.

The organ solo in the symphony which opened part two was performed by James McVinne, on-stage and costumed playing a chamber organ on a platform spinning round in the midst of the field of candles - just one of the visual images which was inexplicable yet stunning. In the pit the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, with continuo from Luise Buchberger (cello), Chi-Chi Nwanoku (bass), Paula Chateauneuf (theorbo), Luke Green (harpsichord) and Bernard Robertson (organ), were directed from the harpsichord with aplomb by Ivor Bolton. He drew strong, characterful playing from the orchestra and the work gave plenty of scope for individuals to shine, but also clearly gloried in the varied sounds of Handel’s orchestra.

Barrie Kosky has a very distinctive theatrical language and the big virtue of his production of Handel’s Saul was the way he used it unashamedly but always expressively. The first night audience at Glyndebourne reacted extremely positively, and clearly enjoyed some of the elements (such as the dancing) which I found more disturbing. This was a truly memorable event, as Kosky and his collaborators and cast had created a strong theatrical event, really bringing Handel’s theatre of the mind to life on stage.

Robert Hugill

Cast and production information:

Saul:Christopher Purves, David: Iestyn Davies, Merab: Lucy Crowe, Michal: Sophie Bevan, Jonathan: Paul Appleby, Abner/High Priest/Amalekite Benjamin Hulett, Doeg: Daniel Shelvey, Witch of Endor: John Graham-Hall. Director: Barrie Kosky, designer: Katrin Lea Tag, choreographer: Otto Pichler, lighting: Joachim Klein. Conductor: Ivor Bolton, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment; Glyndebourne Festival Opera, 23 July 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/%C2%A9BC20150718_SAUL_147.png image_description=Christopher Purves as Saul [Photo by Bill Cooper] product=yes product_title=Saul, Glyndebourne product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: Christopher Purves as SaulPhotos by Bill Cooper

Roberta Invernizzi, Wigmore Hall

‘Here’ was Verona, just one of the Italian cities — Venice, Milan, Pavia, Rome and Mantua among others — in which Vivaldi had, since the performance of his opera Ottone in Villa in Vicenza in 1713, built ‘my name and reputation throughout Europe having composed ninety-four operas’, as he puts it in another letter, of 1739.

After his death, Vivaldi’s popularity waned; even the perennial concerti and instrumental works were little-known before the revival of interest in the composer’s music at the start of the 20th century. In recent years, that interest has stretched to his operatic oeuvre and around 50 operas have been rediscovered (some of the 94 mentioned were probably pasticci); there have been acclaimed performances and recordings by artists such as Cecilia Bartoli and Europa Galante, and by Roberta Invernizzi and La Risonanza (directed by Fabio Bonizzoni) who in 2012 released a CD of arias by Vivaldi (Glossa GCD922901).

This concert at the Wigmore Hall paired Vivaldi with Handel: a sort of operatic head-to-head. The programme was well-planned: each half focused on the vocal work of one composer, a selection of arias framing an instrumental work by the other composer. The arias themselves formed a sequence of contrasting moods and affekts, almost like movements of a symphony.

Invernizzi’s strengths were immediately on display in the opening aria, ‘Da due venti’ from Vivaldi’s Ercole su’l Termodonte, a fiery number in which Hippolyte, sister of the Queen of the man-hating Amazons, despairs in confusion having fallen in love with a man. Utterly committed to the drama, animated in delivery, Invernizzi has a real feeling for character and her portrayal of Hippolyte’s distress was visceral and intense. Her soprano has a thrilling glossiness and radiance; it is an immensely agile and she used it flamboyantly in the fierce fioiriture and wide leaps which conjure the ‘sea agitated by two winds’ to which Hippolyte compares her heart.

However, here and throughout the evening, vivid theatrical intensity was sometimes acquired at the expense of musical accuracy. Invernizzi employed a wide, weighty vibrato which — whatever one argues about ‘authenticity’ — adversely affected her control of pitch, and upper notes were repeatedly approached from below. In the slower numbers particularly, she struggled to shape the line: she tended to slide between notes rather than create a clean line, and there were some ungainly and distracting swells which tempered her bright, clean sound with a rather whiny edge. Her manner of performance could also be diverting: singing from the score in the Vivaldi-focused first half, Invernizzi whipped through the pages (presumably she was using an orchestral score rather than a vocal score) at great pace and with extravagant gestures, creating a great flapping and rustling, particularly as she raced back to the opening page for the da capo repeat.

‘Ombre vane, ingiusti orrori’ from Griselda was more reliable and show-cased Invernizzi’s rich tone and vocal intensity. There was an unearthly quality to the singer’s unaccompanied declamation, ‘Empty shades, iniquitous horrors’ as Constanza, Griselda’s daughter, expresses her fears, and also greater fluidity of line; the soprano’s strong, burnished lowered register was in evidence when Constanza cries in horror at the cruelty of fate. Problems of intonation and phrasing returned, however, in ‘Se mai senti spirarti’ from Cantone in Utica, where the tuning of the octave leaps was often approximate and where there was poor control of line. This is a ravishing aria of seduction, in which Caesar declares his passion for his enemy’s daughter, but the evenness and mellowness required were lacking, which was a pity as the muted violins and lone pizzicato viola of the accompaniment were deeply atmospheric.

The final Vivaldi aria, ‘Rete, lacci e strali adopra’, from Dorilla in Tempe made for a more confident and satisfying conclusion to the first half of the programme. Invernizzi’s coruscating soprano powerfully captured Filindo’s anger and frustration as, rejected by Eudamia, he compares his pursuit to a futile hunt. Here, the coloratura was both vivid and well-controlled; the soprano raced fierily through the wide-ranging scales, arpeggios and melismas with heroic fury and brilliance.

My reservations continued after the interval in the three Handel arias presented. ‘Piangerò la sorte mia’ from Guilio Cesare (in which Cleopatra laments losing both the battle against her brother Tolomeo and her beloved Caesar) suffered from a mannered emphasis on particular notes which disrupted the line, affected the tuning and thus weakened the dramatic intensity — although, as in the Vivaldi pieces heard earlier, the agitated ‘b’ section showed Invernizzi’s suppleness. Rodelinda’s expression of rhapsodic joy and longing for her husband, ‘Ritorna, o caro’, achieved a more tender simplicity and refinement. And, Invernizzi came into her own in the final aria, ‘Da tempeste’ from Guilio Cesare, conjuring great excitement as Cleopatra celebrates her liberation by Caesar from the clutches of Tolomeo and anticipates the victory that is sure to follow. Again, the soprano negotiated the coloratura with impressive agility and athleticism, and theatrical flair, and she used dynamics judiciously to shape the structure of the whole. Interestingly, Invernizzi stepped back from the music stand for this aria and, singing from memory, she seemed altogether more at ease.

La Risonanza, directed with verve and precision by Fabio Bonizzoni, were exemplary accompanists. Bonizzoni kept the pace pulsing and the strings alert, and his pounding continuo was invigorating. The players were attentive to every detail and played, by turns, with tremendous vigour and panache, and with grace and sensitivity. The string tone in the two instrumental interludes was beguiling. Handel’s Overture to Rodrigo was full-toned, but still airy and light, and was enhanced by lovely solos from leader Carlo Lazzaroni. String flourishes and florid ornaments were meticulously executed in Vivaldi’s Sinfonia to Dorilla in Tempe.

There were two splendid Vivaldi encores — from Ottone in Villa and the oratorio Juditha triumphans — in which Invernizzi seemed more relaxed. In the former, she at last found a floating, pure line of immense beauty. But, this fine ending to the recital could not quite dispel all my misgivings.

Claire Seymour

Performers and programme:

Roberta Invernizzi, soprano

La Risonanza: Fabio Bonizzoni (director, harpsichord); Carlo Lazzaroni, Laura Cavazzuti, Silvia Colli, Claudia Combs, Ulrike Slowik and Rossella Borsoni (violins); Livia Baldi (viola); Caterina dell’Agnello (cello); Vanni Moretto (double bass).

Vivaldi: Ercole su’l Termodonte RV710, ‘Da due venti’; Griselda RV718, ‘Ombre vane, ingiusti orrori’; Handel: Overture from Rodrigo HWV5; Vivaldi: Catone in Utica RV705, ‘Se mai senti spirarti sul volto’; Dorilla in Tempe RV709, ‘Rete, lacci e strali adopra’; Handel: Giulio Cesare in Egitto HWV17 ‘Piangerò la sorte mia’; Vivaldi: Dorilla in Tempe RV709, Sinfonia; Handel: Rodelinda HWV19, ‘Ritorna, o caro e dolce mio tesoro’; Giulio Cesare in Egitto HWV17, ‘Da tempeste il legno infranto’.

Wigmore Hall, London, Tuesday 21st July 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Roberta-Invernizzi-credit-Ribaltaluce-Studio-3.png image_description=Roberta Invernizzi [Photo by RibaltaLuce Studio] product=yes product_title=Roberta Invernizzi, Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Roberta Invernizzi [Photo by RibaltaLuce Studio]July 23, 2015

Apotheosis Opera to Stage Tannhäuser

The cast of 35 will be lead by NICHOLAS SIMPSON (Die Tote Stadt, Silent Night, Opportunity Makes the Theif) as Tannhäuser, AMBER SMOKE (Die Walküre, La Clemenza di Tito, Threepenny Opera) as Elisabeth, and JODI KAREM (Santuzza, Vesperae solennes de confessore, Requiem) as Venus. The production will feature a full orchestra lead by MATTHEW JENKINS JAROSZEWICZ (Flight, Gianni Schicchi, Suor Angelica), who is also the Artistic Director of Apotheosis. Jaroszewicz will serve as director, musical director, and conductor, with choreography by MAAYAN VOSS DE BETTANCOURT, scenic design by GALEN KIRKPATRICK, and costume design by NED CHRISTENSEN.

TANNHÄUSER is a unique and powerful dramatic opera in three acts with music and text by Richard Wagner. History and myth collide in Wagner’s renowned early masterpiece, which is set in 13th century Germany and based on the German legends of a real Minnesinger and his relationships with the goddess Venus and a pure young maiden.

Tickets are available for $15, $25, and $45, and can be purchased at tannhauser2015.org.

APOTHEOSIS OPERA seeks to bring fresh energy into the New York opera scene by connecting new performers with new audiences. They create affordable, fully-staged, English-language productions of large-scale works to make opera more accessible to a wider audience. Opera is hot when its stars shine brightly and Apotheosis productions give some of New York’s most talented young performers the game-changing opportunity to sing big roles for the first time. The upcoming production of Tannhäuser will largely feature college students, recent graduates, and other emerging artists in its cast and creative team.

Website: http://www.tannhauser2015.org/

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rehearsal-with-full-vocal-personnel%2C-7.15-4.png image_description=Apotheosis Opera rehearsal photo product=yes product_title=Apotheosis Opera to Stage Tannhäuser product_by=Press release by Apotheosis Opera product_id=Above: Rehearsal photoMontemezzi: L’amore dei tre Re

In Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges the King of Clubs, the ruler of an imaginary kingdom, tries to cure his son’s hypochondria with laughter. In Montemezzi’s vicious melodrama a blind king, Archibaldo menacingly guards his son’s wife from her former lover: there is none of Prokofiev’s colour, fairy-tale and satire, just abundant black fiendishness and slaughter.

Written in 1913, L’amore dei tre Re is a rich amalgam of musical influences: Wagner, Debussy, Puccini and Strauss — and the soaring melodic lines also recall the bel canto idiom of the early nineteenth century. The libretto (by Sam Benelli, based on his play of the same title) bears the heavy imprint of both Pelléas and Mélisande andTristan und Isolde, with, in the closing moments, a dash of Romeo and Juliet thrown in. But, Montemezzi whips up a psychological maelstrom more than equal to any of his operatic predecessors — and, in a matter of only 95 minutes. It’s surging, heady stuff — but not without musical sophistication, as Opera Holland Park confirmed in this splendid revival of Martin Lloyd-Evans’s 2007 staging.

The action takes place in the blind King Archibaldo’s castle following his occupation of the kingdom of Altura. (Archibaldo alludes to the figure of Otto the Great, who was Saxon King from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973, and who greatly extended his kingdom and power through foreign invasions and strategic marriages, conquering the Kingdom of Italy in 961.)

Princess Fiora of Altura has been forcibly wed to Archibaldo’s son, Manfredo; with the latter away at war, Archibaldothreatens and imprisons Fiora to prevent her meeting with her former betrothed, Avito. Needless to say, love finds a way … and learning that Fiora has been unfaithful to Manfredo, the King demands the name of her lover. When she refuses he strangles her and then orders her body to be borne to a tomb. Convinced that the secret lover will be unable to resist bidding his beloved a final passionate farewell, Archibaldo laces Fiora’s lips with lethal venom. True to form, Avito does return; but so does Manfredo, and both lover and husband succumb to the poison’s virulent potency.

This neo-medieval verismo, in which the distance of the Dark Ages shrouds the violence in patina of mystery, reaches extremes of psychological melodrama and emotional tension. Director Martin Lloyd-Evans and designer Jamie Vartan make the sensible decision to ignore the medievalism and minimise the set. They place an imposing constructivist concrete block centre-stage, with sloping ramps spanning the wide platform, and perilous stairways creating upper levels. The latter are sensibly used to raise the singers above the enlarged, resplendent and myriad-voiced forces of the City of London Sinfonia who project the relentless score (an almost unalleviated forte or louder) with power and passion. The effect is a visual echo of the monochrome, gravity-defying stairways of Escher’s lithographs, where those who live among each other occupy different planes of existence.

There are few gimmicks but many nice details, as when Archibaldo’s attire becomes increasingly more military as if to demonstrate the growing strength of his dictatorial grip and his monomaniacal ruthlessness. The grey is relieved only occasionally; but tellingly, when Fiora’s white silk veil — which Manfredo has asked her to wave as a sign of her love as he departs — billows from the height of the staircase and is embraced by Avito on the ground below. After Fiora’s death this veil becomes a ribbon of black. The reference to Mélisande’s luxurious hair in which Pélleas is enveloped is obvious, but deft. And, to keep the historical context in our minds — both that of the medieval past and the era of post-unification Italy when the opera was composed — two chorus members daub the castle walls with name of the 1920s anti-fascist resistance movement: ‘Giustizia e Libertà’.

It was only at the end of the opera as the chorus stirred themselves to revolutionary action and Fiora lay on a hospital trolley draped with the tricolour bandiera d’Italia that the focus seemed to turn a little too far from the private towards the political. I wasn’t sure, either, whether in the closing moments it was necessary for the masses, led by Archibaldo’s Italian guard Flaminio, to actually pull the trigger on their oppressor: we are left with the echo of gun-shot rather than the pathos of a blind tyrant with a pistol poised at the back of his head. Moreover, Archibaldo’s assassination is a directorial addition. In the libretto, Archibaldo enters the tomb and, finding Manfredodesperately kissing the infected lips of Fiora, assumes that he has trapped the guilty lover. When he discovers the truth, he wraps his arms about the body of his dying son, and it is the sightless old King’s lament with which the opera ends: ‘Ah! Manfredo! Manfredo! Anehe tu, dunque, Senza rimedio sei con me nell’ombra! Manfredo! Manfredo!’ (Ah! Manfredo! You too, then, with no hope of remedy, are with me in the shadows!).

As the focus for the violent passion of the ‘three kings’ — Avito, Manfredo and Archibaldo — and the catalyst of the triple tragedy, Fiora is also the opera’s single female role. Natalya Romaniw was more than up to the challenges and walked off with the vocal honours, though there was strong competition. The smooth arches of Montemezzi’s languorous melodic lines were excellently projected with no sign of a lessening of stamina. Romaniw’s tone was thrilling and radiant: but she was able to capture both Fiora’s sensuousness and her more ethereal delicacy — for upon her death the male chorus ask: ‘Who makes the lily, which has now come fall! The spring was killed among the flowers!’ (‘Chi ci rende il giglio, che venuto è ormai l'autunno! La primavera fu uccisa tra i fiori!’)

Initially I was not entire convinced by the supposedly all-consuming desire of Fiora and Avito, despite the erotic embraces on stage. Joel Montero’s characterisation of Avito was slightly one-dimensional to begin with but he found a true Italianate sound of great sweetness in the Act 2 duet and later a heroic, noble ring. His closing monologue — ‘Fiora, Fiora. È silenzio: siamo soli.’ (Fiora, Fiora. All is silent, we are alone.) — was captivating. Overcome by emotion, this Avito seemed genuinely close to death when he staggered from the bitter Manfredo and asked, ‘What do you want? … Can you not see that I can scarcely speak?’ (‘Che vuoi tu? Ma non vedi ch'io non posso quasi parlare?’)

Simon Thorpe used his lyrical baritone particularly well in the calamitous final scene; his tone was well-focused, revealing Manfredo’s humanity. As the blind patriarch, the American-Russian bass Mikhail Svetlov, reprised his role from 2007. This was a terrifying, threatening but mesmerising portrait: Mussolini meets a demented Arkel. In Act 1, Svetlov’s generous, dark-toned voice was occasionally covered at the bottom by the orchestra — one of perils of an open pit — but whenever on stage Svetlov was never less than utterly commanding. His convincing depiction of a blind man showed real dramatic intelligence: his infirmity added poignancy but also malignancy to his assertions of power. He paced the portrayal well too: we can see from the start that Archibaldo is insanely fanatical, but Svetlov slowly released his repressed, self-destructive desire for Fiora. This toxic lust culminated in a chilling and ferocious throttling: Archibaldo slumped over Fiora’s body in post-coital exhaustion, then — when discovered by Manfredo — brusquely kicked her dead body aside. Aled Hall also recreated his 2007 role and was excellent as Flaminio, pushing what is a fairly minor role to the centre of the drama.

Under Peter Robinson’s baton, the City of London Sinfonia surged with turbo-thrust towards a perennial precipice, much like the protagonists’ pulsing heartbeats. The score stabbed like a sword, and the outré harmonies swerved unpredictably. But, despite the orchestral extravagance and extroversion, the details didn’t get lost in the impassioned outbursts.

L’amore dei tre Re is melodramatic and certainly not subtle. It wouldn’t take much for a staging to slip into the realms of caricature and farce, but this OHP production never strays near parody and as the sun set over South Kensington we were all enveloped by the growing darkness. It’s compelling stuff.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Fiora: Natalya Romaniw, Avito: Joel Montero, Manfredo: Simon Thorpe, Archibaldo: Mikhail Svetlov, Flaminio: Aled Hall, An Old Woman: Lindsay Bramley, Ancella: Jessica Eccleston, Una Giovanetta: Abigail Sudbury, Un Giovanetto: Timothy Langston, Una Vecchia: Lindsay Bramley, Voce Interna: Naomi Kilby; Conductor: Peter Robinson, Director: Martin Lloyd-Evans, Associate Director: Rodula Gaitanou, Designer: Jamie Vartan, Chorus Master: John Andrews. Opera Holland Park, Wednesday 22nd July 2013.

L’amore dei tre Re will be performed on 25, 28 and 30 July, and 1 August.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/FS-Lamore-e1420651990372.png image_description=L’amore dei tre Re at Opera Holland Park: product=yes product_title=Montemezzi: L’amore dei tre Re product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: L’amore dei tre Re at Opera Holland Park:Prom 4: Andris Nelsons

I could really find nothing about which to cavil at the orchestral performance. Andris Nelsons’s conducting, however, remained distinctly mixed in quality. He eschewed fashionable ideas concerning tempo and offered a refreshingly slow introduction. The main body of the Overture started intriguingly post-Mozartian fashion, seeming — surprisingly — to hint at The Marriage of Figaro. However, Rossini soon, bizarrely, seemed to supplant Mozart, and we found ourselves in the world of Toscanini. The Beethovenian weight of Klemperer was nowhere to be heard. If ‘Italianate’ Beethoven were your thing, you would probably have liked it more than I did.

John Woolrich’s Falling Down, ‘a capricho for double bassoon and orchestra’, followed. The solo part was taken by Margaret Cookhorn, the dedicatee of this piece, first performed by the same forces in 2009 as a CBSO commission. They all seemed to play it very well indeed; I wish I could have thought more of the work itself. A colourful, spiky, somewhat Stravinskian opening augured well, its material reappearing throughout the quarter of an hour or so. Some harmonies put me in mind a little of Prokofiev, and there was indeed, something of a balletic quality. Antiphonally placed timpani had an important role, well taken. But once one is past the interesting ‘experience’ of a concertante piece for contrabassoon, Falling Down seems, at best, over-extended. There is only so much it can do as a solo instrument but, more to the point, what soloist and orchestra do soon seems repetitive. I have responded much more readily to the composer’s Monteverdi reworkings.

The performance of the Ninth Symphony grew in stature, but I am afraid this was not — for me, although the audience in general seemed wildly enthusiastic — that elusive, compelling modern performance we all crave. Daniel Barenboim’s Proms performance in 2012 was nowhere challenged — not least since there was no doubt whatsoever in Barenboim’s performance that the work meant something, and something of crucial, undying importance at that. There was good news in the first movement. First, it was not taken absurdly fast; nor was it metronomic in its progress. And yet, despite the undoubted excellence of the CBSO’s playing, I found myself at a loss as to what the music in performance might actually mean. Too often, extreme dynamic contrasts — somewhat smoothed over by the notorious Albert Hall acoustic — seemed just that; why was a phrase played quite so softly? There was wonderful clarity, enabling woodwind lines not just to be heard, but to sing. What, however, were they singing about? There was real menace, though, in the coda, even if it seemed somewhat to have come from nowhere. Applause: really?!

The Scherzo was taken fast, very fast: nothing wrong with that. My chief reservation remained, however, and ultimately this was a smoothly ‘reliable’ performance rather than a revelation. Where were the anger, the vehemence, the human obstreperousness of Beethoven? Applause proves still less welcome here. The slow movement was taken at a convincing tempo, its hushed nobility, with especial thanks to euphonious woodwind, greatly welcome. I was less convinced that the metaphysical dots were joined up, or even, sometimes, noticed. Whatever my doubts, though, there was no denying the beauty of the playing (an intervention from an audience glass towards the close notwithstanding).

Nelsons forestalled applause, thank goodness, by moving immediately to the finale. He and the orchestra fairly sprung into and through its opening: very impressive on its own terms, although it would surely have hit home harder, had it been properly prepared by what had gone before. The cellos really dug into their strings too. Nelsons had them and the double basses paly deliciously softly for their recitative; now, a true sense of drama announced itself, expectant rather than merely soft. Bass-baritone Kostas Smoriginas delivered his ‘proper’ recitative, ‘O Freunde …’, with almost Sarastro-like sincerity and deliberation. I liked the way the rejection of such ‘Töne’ was no easy decision. The soloists as a whole did a good job; that there remains a multiplicity of options, and dare, I suggest, a residual insufficiency to any one quartet, says more about Beethoven’s strenuousness of vision and humility before his God than performance as such. The CBSO Chorus, singing from memory, was quite simply outstanding. Weight and clarity reinforced each other rather than proving, as so often, contradictory imperatives. Nelsons imparted an unusual sense of narrative propulsion, almost as if this were an opera, or at least an oratorio: I am not sure what I think of such a conception, but it was interesting to hear it, and there was no doubting now the conviction with which it was instantiated. The almost superhuman clarity of the chorus’s words — ‘Und der Cherub steht vor Gott!’ a fitting climax to that first section — certainly helped. It was fun, moreover, to be reminded of the contrabassoon immediately afterwards. (Was that the tenuous connection with the Woolrich piece?) The infectious quality to the ‘Turkish March’ brought with it welcome reminiscences of Die Entführung aus dem Serail. And the return to ‘Freude, schöner Götterfunken’ proved exultant in that deeply moving way that is Beethoven’s own. (If only the abuse of this work by the European Union had not had me think of the poor Greeks at this point — but, on second thoughts, that was probably a good thing too.) If only Nelsons could have started again, and reworked the meaning he seemed to find here into the earlier movements, especially the first two, we might have had a great performance. As it stood, there remained a good deal later on to have us think.

Mark Berry

Programme and performers:

Beethoven —The Creatures of Prometheus, op.43: Overture; Woolrich — Falling Down (London premiere); Beethoven — Symphony no.9 in D minor, op.125.

Margaret Cookhorn (contra-bassoon); Lucy Crowe (soprano); Gerhild Romberger (mezzo-soprano); Pavel Černoch (tenor); Kostas Smoriginas (bass-baritone); CBSO Chorus (chorus master: Simon Halsey)/City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra/Andris Nelsons (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, Sunday 19 July 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/andris-nelsons.png image_description=Andris Nelsons product=yes product_title=Prom 4: Andris Nelsons product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Andris NelsonsBBC Proms: The Cardinall’s Musick

There was a sell-out audience for this first Chamber Music Prom of the 2015 season, at the Cadogan Hall in South Kensington, and the early music specialists The Cardinall’s Musick, directed by Andrew Carwood, delighted with a compelling performance of Latin and English motets and anthems by Tallis.

Fittingly, the Cadogan Hall began its life as a church. Established in 1907 as a New Christian Science Church, a declining congregation led to its closure in 1996 but it was purchased by the Cadogan Estate in 2000 and re-furbished as a concert hall four year later. Careful attention was paid to the environmental and performance acoustic during the refurbishment; and, if the resonance is not quite equal to that of the Reformation churches and cathedrals in which Tallis’s sacred compositions were first heard, the Cardinall’s Musick sang with full tone which reverberated richly, as they illuminated the diversity of Tallis’s vocal textures. Noteworthy too was the way in which individual voices emerged from the polyphonic ensemble, as Carwood adeptly maintained an excellent balance between soloists and the collective. His fluid, easy direction allowed the contrapuntal forms to evolve organically while sustaining forward momentum. And, although the Hall seats 950 people, the ensemble managed to create a surprising intimacy, drawing the listener into the performance, the sensitivity and dignity of which reminded one of the original function of these compositions - to express and inspire devotion.

The Cardinall’s Musick

The Cardinall’s Musick

The opening work ‘Videte miraculum’ (the responsory for Candlemas) took a little while to settle, perhaps because of the strange dissonances which characterise its opening point of imitation and its frequent alternations between soloist, solo groupings and full choir. But, the emergence of the unadorned chants between the choral sections were expressive and the multi-voice responses created energy as parts of the chant were repeated, blossoming in tone. The motet ‘Suscipe quaeso’ developed from the solemnity of its narrow-compassed beginnings into a stunningly lavish, beautifully balanced rhetorical appeal, and the repeated questions of the second part were absorbingly insistent. Perhaps there might have been more emphasis placed on the metrical and harmonic oddities of the brief ‘O nata lux de lumine’, though the concluding phrase was characterised by a beautiful simplicity and glow. In the 5-part ‘O salutaris hostia’ the short melodic ideas developed with vitality. The passing of the imitative motifs from the highest voice to the lowest created a sense of expanse, as the text expressed hope of heavenly salvation, while the intricate appeals for strength in the face of earthly enemies and woes in the latter part of the motet were elucidated with clarity, building to invigorating repetitions of the final phrase. ‘O Sacrum Convivium’ was utterly compelling in the way that the close imitation built in intensity while still remaining airy and lucid.

There were English anthems too, beginning with the 4-part ‘O Lord, give thy holy spirit’. Here, I’d have liked a little more emphasis on the harmonic nuances which underscore the textual meaning. However, the consistency of tone and intonation in the opening section of ‘Hear the voice and prayer’ made for a powerful entreaty, while the more extended sequential imitation of the appeal ‘That thine eyes may be open toward this house’ and the elision into the final prayer, ‘And when thou hear’st, have mercy upon them’, was persuasive. ‘Why fum’th in fight?’ was one of the works that Tallis contributed to the Psalter prepared by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker, in 1567, but is better known today as the melody of the work it inspired: Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis. The Cardinall’s Musick made the text dramatic, blending their voices beautifully, and the modal harmonies were powerfully expressive, stripped of some of the sentimentality which can colour Vaughan Williams’s work.

Contrast and complement was provided by another composition inspired by Tallis. Though it takes its name from Thomas Wolsey (the Roman Catholic Cardinal and Lord Chancellor who rose to eminence during the reign of Henry VIII before falling from favour when he failed to satisfy the King’s political and matrimonial whims), the Cardinall’s Musick frequently turns its attention to music of its own day, and has given premieres of works by composer such as Michael Finnissy and Judith Weir. On this occasion it presented the premiere of Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s ‘From the Beginning of the World’, a composition for 8 voices which takes it text from the ‘German Treatise on the Great Comet of 1577’ by Tycho Brahe (1546-1601). Speaking in the Hall to BBC Proms presenter Petroc Trelawny, Frances-Hoad explained that she had looked for a text which was representative of Tallis’s age but also spoke to our own times: the Great Comet was interpreted as heralding an apocalypse, a sign of God’s displeasure at man’s sinfulness, but also as a sign of rebirth, an opportunity to repent: ‘It thus behoves us to use well our short life here on earth, So that we may praise him for all eternity’ - a message that Frances-Hoad suggested modern politicians, and indeed we all, might do well to remember.