September 27, 2016

Oxford Lieder Festival: in conversation with Julius Drake

The fifteenth Oxford Lieder Festival (14-29 October 2016) will see the focus shift to Robert Schumann. This year’s ‘Schumann Project’ will present a unique survey of Schumann’s complete songs, exploring diverse aspects of the composer’s life and work: his innate Romantic sensibility; his complex, troubled personality - which, paradoxically fuelled such creative fertility; his life and times, friends and contemporaries; his influences and his legacies; and his literary and artistic interests. Alongside the core lieder repertoire, performances of Schumann’s chamber music and choral works, as well as study events, masterclasses, lecture-recitals, film screenings and talks, will place Schumann in the context of contemporary political, cultural energies and incidents.

Birgid Steinberger, with whom Drake will perform songs by Schubert and Brahms on 18 October at the Holywell Music Room, Oxford

Birgid Steinberger, with whom Drake will perform songs by Schubert and Brahms on 18 October at the Holywell Music Room, Oxford

In addition to Schumann's complete songs, the Festival will feature many works by his friends and contemporaries, including Mendelssohn and Brahms, and the 29 songs composed by Schumann’s wife, Clara, whose death 120 years ago is also marked in 2016.

One musician who has been involved with the Oxford Lieder Festival almost from its conception is pianist Julius Drake, with whom I recently met to discuss this year’s Festival and his passion for lieder - and chamber music - more generally.

Kynoch Sholto

Kynoch Sholto

Drake is full of admiration and respect for Sholto Kynoch. From small beginnings - a few performances, sparsely attended - has grown a thriving festival of international repute, and Drake notes that Kynoch, himself an esteemed pianist, has been the driving force behind this blossoming and achievement. Indeed, Drake observes that it is often such a single individual - and sometimes a figure whom one does not necessarily anticipate will possess such enabling energy and force - whose passion, commitment, stamina and practical foresight creates the environment in which music thrives and communicates with startling vividness and freshness; influencing and developing audiences year on year, despite what might seem initially inauspicious circumstances.

I ask Drake if Schumann’s lieder present different challenges and opportunities from those offered by Schubert. His observations are characteristically astute. Schumann’s 200 or so songs, he notes, date principally from the year 1840 - the Liederjahr during which he wrote no less than 138 songs. In the preceding years, 1832-1839, Schumann had written almost exclusively for the piano, but in February 1840 Schumann experienced a creative outbreak which was expressed almost solely through the medium of song - the piano, he wrote, was now ‘too narrow to express my thoughts’. It may be true that Schumann was looking for a new medium through which to express his overwhelming love for his new bride, Clara (née Wieck) but, as Drake observes, the songs are essentially a continuation of the piano miniatures which had preoccupied the composer in the preceding years:Kinderszenen Op.15, Kreisleriana Op.16, Arabeske Op.18, Blumenstück Op.19, Humoreske Op.20, Noveletten Op.21. Moreover, the vocal lines often double the upper voice of the piano texture, and Drake envisages Schumann extemporising these songs at the piano.

Prior to the 2015 Oxford Lieder Festival I met with baritone Mark Stone, who commented that he felt that the lieder genre makes particular demands upon the listener, and that thus there is a challenge to sustain an audience for this repertory. I ask Drake if he concurs. He agrees that lieder recitals make demands on audiences: the success of the final result relies on a triumvirate of contribution - from the composer, the performers, and the listeners. At venues such as the Wigmore Hall, which presents more lieder recitals than any other venue in the world, there is a dedicated and well-informed audience; a body of listeners familiar with the demands of listening to the music at the same time as reading the text (and its translation) and observing the singer’s physical demeanour and gesture. And, sympathetic to the cultural and moral endeavour.

To some extent, the Oxford Lieder Festival audience is similarly composed and devoted to the art form. The real challenge today is to build new audiences, especially among the young whose educational and creative experiences are perhaps unlikely to comprise exposure to the sort of concentration and immersion that live chamber music - in its intimacy and intensity - involves. Drake recounts an anecdote concerning the imminent demise of a Steinway piano in the possession of Brent council which, through the enterprise of a particular primary school teacher, ‘lived’ another day - albeit in the form of a ‘replacement’ Steinway D, offered by the company when the sound-board of the original was found to be cracked - to provide young children with a potentially life-changing series of classical music concerts, facilitated by Drake. As he says, there will always be musicians - they are driven from within; it is the audiences whose confidence, familiarity and enthusiasm is inspired from without, that society - and the education system - must nurture.

Julius Drake - Photo credit: Marco Borggreve

Julius Drake - Photo credit: Marco Borggreve

Which leads to Drake’s own musical education and career. After studies at the Purcell School, he entered the Royal College of Music anticipating a future career as a solo pianist. But, his first experience of chamber music put a stop to that, somewhat unexpectedly. He tells me that after that initial, revelatory experience of shared music-making he no longer had any desire to walk onto a stage alone; his future music-making would be a collective experience. An introduction to song followed and a pathway opened naturally.

When I suggest that a career as a ‘piano accompanist’ is not a typical ambition for an aspiring keyboard player Drake, quite rightly, disputes my terminology! He dislikes, in fact vociferously rejects, the notion of ‘accompanist’. And, while there are some pianists who are happy to ‘follow’ the ‘lead’ of singer or instrumentalist, Drake has never been one such. Indeed, when I re-read a review which I wrote of Drake’s Snape Proms recital this August with tenor Ian Bostridge, in which they presented songs by Schumann and Brahms, I remembered how much I had relished Drake’s creative contribution:

Drake was a superb accompanist, as alert as Bostridge to every nuance of the Romantic cast of mind which the songs embody - and equally equipped with the technique and artistry to craft those nuances into a unity which is both coherent and contradictory. The ‘dark splendour’ of the piano tone showcased the bright gleam of the singer’s flowering adoration in ‘Es leuchtet meine Liebe’, while the stature of the chordal postlude confirmed the inescapable tragedy of the gloomy folk-tale of love. In ‘Mein Wagen rollet langsam’ the tight, dotted rhythms of the rolling carriage alternated with a tender chord sequence, as the charms of nature lulled the poet-speaker into a seductively solipsistic dream; but, Bostridge’s murmured will-o’-the-wisps - who ‘hop and pull faces,/ So mocking yet so shy’ (‘Sie hüpfen und schneiden Gesichter,/ So spöttisch und doch so scheu’ - took on an ominous tone as the goblins whirled together like mist.

[…]

Drake’s accompaniments were inextricably fused with the vocal expression. The unstable modulations at the end of the second verse of ‘Alte Liebe’ (Old age), and the diminished harmonies which underscore the opening of the third were wonderfully expressive of what one scholar has called Brahms’s ‘masochistic nostalgia’, as the poet-speaker ponders, ‘Es ist, als ob mich leise/ Wer auf die Schulter schlug’ (It is as if someone tapped me on the shoulder). And, the piano postlude confirmed and enhanced the compulsion, derived from sadness and acceptance, which is expressed in Bostridge’s final phrase, ‘Ein alter Traum erfaßt mich/ Und fürht mich seine Bahn.’ (An old dream takes hold of me and leads me on its path). The entwining cascades of ‘Sommerfäden’ (Threads of summer) embodied both the exterior world - the gossamer threads of summer light which the poet-singer imagines as a tapestry of ‘Liebesträume’ (dreams of love) - and a dark interiority, as he sees his own fate hanging by such a brittle thread. Similarly, the spirals which surged from the depths in ‘Verzagen’ (Despair) were both the raging storm-sea and the poet’s lurching heart in love-sickness.

The Holywell Music Room, Oxford

The Holywell Music Room, Oxford

Although Drake spends a considerable proportion of his time working with singers, instrumental chamber music still forms a significant part of his music-making, and I ask about the respective challenges in terms of both preparation and performance. Drake explains that preparing for a song recital involves extra-musical dimensions: that is, one must not only have a technical and expressive grasp of the notes on the page, but one must also understand both the overall ‘meaning’ of the text and the precise intent and inferences of particular words.

We also discuss recital programmes. The Schubert/Schumann Project concerts at the Oxford Lieder Festival obviously focus on a single composer’s work, and I comment that, as a listener, I find of late that I am less captivated by programmes which offer works by various composers. Drake admits that when compiling and preparing a recital programme, it is important for the performers to devise a sequence which produces a natural, inevitable progression between songs - each of which may only last between one to three minutes. But, he argues convincingly that it is possible to construct multiple composer programmes - whose works may or may not be linked by a ‘theme’ - which create a fluent progression from song to song, even though diverse idioms and ages are represented.

To conclude our conversation, I ask Drake if there are any outstanding musical ambitions or challenges which he wishes to fulfil. Drake mentions that cellist Natalie Clein has asked him to perform Schubert’s last piano sonata at the Purbeck International Music Festival - the Bb major sonata, D.960. Although he loves the solo piano repertory, he has no burning desire to perform as a soloist, but Clein’s suggestion that she senses that this sonata is ‘your piece’, that ‘it sings’, is clearly seductive. But, Drake’s general response is both chastening and reassuring: there are no specific ‘landmarks’ to assail, but he wishes to keep discovering new music - after all, the song repertory is expansive - and to continue to perform with fellow, like-minded musicians. These are aspirations with which chamber music lovers and, especially, lieder enthusiasts will undoubtedly concur.

Claire Seymour

Julius Drake and Birgid Steinberger will perform music by Schubert and Brahms at the Oxford Lieder Festival, on Tuesday 18th October 2016: https://www.oxfordlieder.co.uk/event/636 .

image=http://www.operatoday.com/JD%202%20Sim%20Canetty-Clarke.png image_description=Julius Drake product=yes product_title= product_by= product_id=Above: Julius DrakePhoto credit: Sim Canetty-Clarke

September 25, 2016

Così fan tutte at Covent Garden

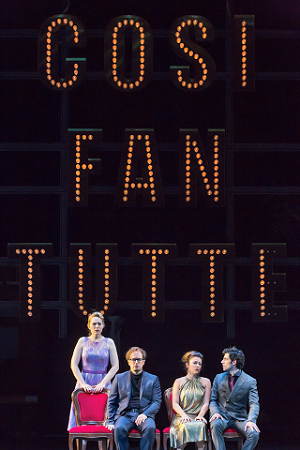

In case we don’t get it - and, perhaps, to guard against politically incorrect sexism - designer Ben Baur’s huge neon sign, Così fan tutti, looms didactically and disapprovingly over the closing scenes.

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Daniel Behle as Ferrando, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi, Alessio Arduini as Guglielmo © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Daniel Behle as Ferrando, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi, Alessio Arduini as Guglielmo © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

But, back to the beginning, which in fact is the ‘end’ - though not T.S. Eliot’s eternal wholeness - as five characters in elaborate period costume are encouraged by a master-of-ceremonies to accept the audience’s applause with self-congratulatory zeal and faux obsequiousness: the full eighteenth-century curtain-call monty.

There is a dash of unintentional irony, perhaps, given that at Covent Garden of late, the first-night call seems to have become an opportunity to hurl obligatory boos at the director and designer. But, more than that, bringing the ‘cast’ in front of the curtain, into the small space which (as the Anglo-Irish dramatist and critic Dion Boucicault wrote in 1889) belongs to both the stage and the auditorium, placed these singers/actors in a liminal space between the characters they represent and their real selves.

And, the conduit between reality and artifice was further strengthened by the arrival of the ‘real’ cast in the aisles of the auditorium itself, dressed in contemporary attire and flapping their ROH programmes as they anxiously sought to locate their allocated seats. Presumably in these fashionably tardy fashionistas we were supposed to recognise ourselves; and so here, and at other times, the house-lights rose, to ensure that we didn’t miss the point that this show is about ‘us’.

Leaving their belles behind, Ferrando (Daniel Behle) and Guglielmo (Alessio Arduini), awkwardly negotiating the knees of those seated in the front row of the stalls, clamber onto the front-stage to join Don Alfonso (Johannes Martin Kränzle) - the latter no longer an ‘old philosopher’ but a stage-manager/impresario who retains his period costume and, donning a black high-crown hat, all too often resembles the Witch-finder General.

Gloger and Baur then take us on a time-journey which lurches back and forth through the ages, from the Garden of Eden to behind-the-scenes mechanics of the very opera that is unfolding before our eyes. The allusions - cinematic and cultural, theatrical and theological - raise interesting questions, and to encourage us to reflect and relate we are consistently made aware of the self-conscious theatricality before us, as stage-hands in dungarees and doc martins stamp through proceedings, hoisting ropes, shifting sets and carrying out Don Alfonso’s commands.

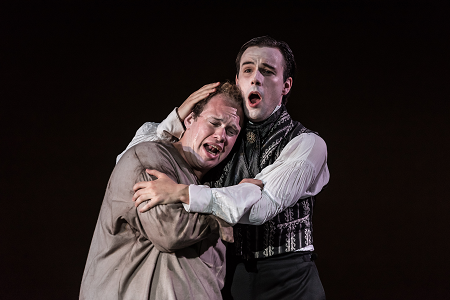

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Daniel Behle as Ferrando, Alessio Arduini as Guglielmo, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Daniel Behle as Ferrando, Alessio Arduini as Guglielmo, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

The histrionic departure of the two men takes place on a replica of the set of that timeless classic of repressed emotion, Brief Encounter, complete with mist-shrouded buffers, hanging nineteenth-century clock and a platform peopled by a crowd of Celia Johnson-Trevor Howard couples clutching each other in desperate duplicate.

Dorabella (Angela Brower) and Fiordiligi (Corinne Winters) first encounter the minimally masked men in a swish cocktail bar framed by Moulin Rouge -style cabaret lights. A wisp of a moustache suffices to convince the girls that they’ve never before met the two charmers in skinny ties and drainpipe trousers. Sabina Puértolas’s Despina - a cynical bartender rather than saucy soubrette - shakes a mean cocktail and delivers ‘In uomini, in soldati, sperare fedeltà?’ with panache worthy of Sally Bowles, atop the bar, astride the bar-stools, pausing only to whip out a blackboard on which to instruct the ladies in lessons of love - in case we’d forgotten that the opera’s subtitle is ‘ossia La scuola degli amanti’. Fun and frivolity were largely dispensed with, though, and as the colour scheme faded from shocking pink to flat grey at the end of the scene (Bernd Purkrabek’s lighting is beautiful throughout), the words uttered by Don Alfonso upon his entry, ‘what a sad and silent atmosphere’, seemed apposite. The gloom escalates and by the Act 2 duet which marks Fiordiligi’s capitulation, ‘Fra gli amplessi’ the storm-clouds are descending, lowered from the flies by Don Alfonso. When Despina’s blackboard later re-appears, her chalk scribbling, ‘Amor cos’è?’ assumes an accusatory, cynical tone.

© ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

© ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

Next stop on our time-travel adventure is the Garden of Eden, complete with fallen apples hastily strewn by a stage-crew caught on the hop, and a serpent-twined tree atop a rounded mound - whose steep slant subsequently provides a convenient ‘slippery slope’ down which the near-errant lovers can slide. When Despina arrives with her magnetic cure for the arsenic-imbibing men, she resembles a biblical prophet who’s wandered in from the wilderness.

ROH. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

ROH. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

During Act 2 we are led behind and before the curtain, venturing backstage and deep into the bowels of the theatre, where Don Alfonso and Despina smoke cigarettes amid the detritus of dismantled props. Ferrando and Guglielmo now don stock oriental garb - high boots, salvars and turbans - so, fittingly, we visit the costume department and as the girls spin mannequins it’s made clear that Fiordiligi and Dorabella are fully aware of the true identity of their ‘Albanian’ suitors - a problematic directorial decision for when Dorabella removes Guglielmo’s shirt she has no doubt, or qualm, about her own disloyalty and it’s not clear who is being ‘seduced’. An interesting twist, perhaps, but one which robs the final ‘revelation’ of its relevance and piquancy.

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi, © ROH. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi, © ROH. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

In a recent interview (Guardian), Gloger commented, ‘Every director of Così fan tutte has to deal with the question of why the women don’t recognise their lovers through their disguises, especially since they get right up close to them … [b]ut if the women are led into a theatrical, imagined space at the very beginning, and if they are seduced into believing fictions, then this contradiction no longer applies’. This suggests that the director thinks that this, or indeed any, opera is ‘real’. Whatever happened to that quintessence of theatre, especially opera, the suspension of disbelief - Shakespeare’s ‘imaginary puissance’?

Whatever. We are duly led through an exquisite eighteenth-century bucolic tableau, down into some shabby green rooms, arriving eventually in an auditorium which presents us with a ‘reflection’ of ourselves, as a line of theatre-goers assembles for Don Alfonso’s ‘Tutti accusan le donne’.

Johannes Martin Kränzle as Don Alfonso. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Johannes Martin Kränzle as Don Alfonso. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

The cast of young singers - billed as ‘up-and-coming - are unanimously good, though on occasion they are almost felled by the fatal flaw in this production, conductor Semyon Bychkov’s snail-like tempi. It was as if Bychkov was so concerned, admirably, to ensure that we heard every instrumental gesture with utmost clarity, that he forgot that he was not painting a picture but a sculpting a drama.

Winters’ Fiordiligi is indeed as ‘steady as a rock’ vocally: she has a bright, ringing top and she agilely leapt through ‘Come scoglio’. But ‘Per pietà’ was so sluggish that I half-expected to hear a hectoring cry, ‘For pity’s sake, get a move on!’

Ferrando’s ‘Un'aura amorosa’ was similarly robbed of its emotional depth by the listless tempo, which was a real pity as Behle exhibited a beautifully sweet and light tenor throughout. He just about coped with Bychkov’s weary pace, but only by reducing his tenor to an almost-whisper in places - the pianissimo was impressive, but the overall effect was to suggest an ambiguous fine-line between emotional tenderness and frailty.

Angela Bower’s Dorabella was rather under-directed. Gloger had apparently decided that the usual hysterical mock-heroics of ‘Smanie implacabili’ were ill-suited to his conception but he did not know what to put in their place, and some table-top antics and arm-swinging did not fill the gap. Alessio Arduini suffered similarly as Guglielmo, lingering in Ferrando’s shadow dramatically, but Arduini has a strong baritone and made a good stab at conveying a credible and independent character.

Sabina Puértolas as Despina. © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

Sabina Puértolas as Despina. © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

Johannes Martin Kränzle showed a good sense of timing and stage-craft, and his baritone is both full-bodied and fluid. It wasn’t Kränzle’s fault that this Don Alfonso was hardly a figure-of-fun; indeed, by the end he seemed a rather smug and self-satisfied nasty-piece-of-work. Sabina Puértolas has quite a weighty soprano and this Despina was well-sung but rather hostile and unforgiving towards the duped duo.

Gloger’s meta-theatrical exploits are all very sophisticated, and not without wit and wisdom, but often they are out of kilter with what the music is saying - and, in fact, with what the libretto itself speaks. When Despina sings to the ‘ladies’, lamenting her own exclusion from their feminine romantic indulgences, the two girls are not actually on stage; the two men may be dressed as West-End wide-boys from the 1950s but their lovers’ can’t tell whether they are ‘Wallachians or Turks’. It might have been better to dispense with Da Ponte completely and start from scratch; it certainly would have been more coherent.

Beethoven may have lamented that in Così Mozart had squandered his genius but to complain that the work is a frivolous fantasy seems to miss the precise point of the opera. The scepticism of Così may seem attuned to our own disenchanted age of disbelief, but surely to appreciate Mozart’s exquisite blend of irony and sincerity we need to wholly abandon verisimilitude, suspend our disbelief and enter the fantasy created by Da Ponte - a world both impossibly absurd and authentically reflective of its time. We may charge the librettist with superficiality and simplification, but Mozart’s music delves deeper and restores truth in all its complexity. Mozart’s score reveals the poetry - the beautiful poignancy - of the inexorable co-existence of hope and doubt in the human heart. Gloger’s Così is simply too clever for its own good.

Claire Seymour

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Così van tutte

Fiordiligi - Corinne Winters, Dorabella - Angela Brower, Ferrando - Daniel Behle, Guglielmo - Alessio Arduini, Don Alfonso - Johannes Martin Kränzle, Despina - Sabina Puértolas; Director - Jan Philipp Gloger, Conductor - Semyon Bychkov, Set designer - Ben Baur, Costume designer - Karin Jud, Lighting designer - Bernd Purkrabek, Dramaturg - Katharina John, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Royal Opera Chorus.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 22nd September 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/1%20JOHANNES%20MARTIN%20KR%C3%84NZLE%20AS%20DON%20ALFONSO%2C%20DANIEL%20BEHLE%20AS%20FERRANDO%20%C2%A9%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20STEPHEN%20CUMMISKEY.png image_description=ROH, Mozart’s Così fan tutte product=yes product_title=ROH, Mozart’s Così fan tutte product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Johannes Martin Kränzle as Don Alfonso, Daniel Behle as Ferrando.Photo credit: © ROH Stephen Cummiskey

September 24, 2016

Plácido Domingo as Macbeth, LA Opera

They premiered it in 1847, a few years before the play appeared in Italian. A lifelong lover of the English Bard’s plays, in 1865, Verdi revised and expanded the opera with the help of Andrea Maffei for presentation in Paris. All of this was before Verdi wrote Otello, which he staged in 1887 or Falstaff, his last opera, which premiered in 1893.

In his program article on Macbeth, Music Director James Conlon notes, “It has been observed that Verdi’s opera is a tragedy for the royal couple but a comedy for the witches.” Director Tresnjak and costume designer Suttirat Anne Larlarb have the dancers representing witches wearing stretch fabrics and long tails. From climbing holds placed high on Tresnjak and Colin McGurk’s shallow set, these witches enjoy watching people fall prey to the machinations of the Macbeths. The set took up the full width of the stage and had an upper level that often accommodated the singing members of the chorus. Its lower level had entrances which included mirrors that reflected the comings and goings of cast members. Matthew Richards' lighting design underscored most of the situations appropriately, but it could have been more subtle for the apparitions.

Placido Domingo as Macbeth

Placido Domingo as Macbeth

Tresnjak told the story in a literal manner that worked well for most scenes. Los Angeles Opera cast the production with glorious voices that filled the auditorium, both literally and figuratively. Plácido Domingo was a baritone Macbeth. Lately, his timbre has become a bit more baritonal and he has resonance on notes below the usual tenor range. Someday members of this audience will tell their grandchildren that they heard Domingo as Macbeth. He sang his part with a robust sound and his portrayal made this fierce king a real person whose lust for power had eaten away much of his soul.

Ekaterina Semenchuk did not have the ugly voice Verdi said he wanted for Lady Macbeth. Hers is a strong instrument with gorgeous overtones that made her duets with Domingo moments to be treasured. She was an ambitious wife who would help her husband attain his goals even if he faltered and she had to act for him. She sang her arias with power and a smooth opulent tone that bloomed in various vocal colors. The Banquet Scene showed her character’s mental progress while the Sleepwalking Scene showed her mind’s disintegration as she emitted clear, colorless tones with little vibrato and a staccato high note at the end.

Placido Domingo (center) as Macbeth and Ekaterina Semenchuk (left) as Lady Macbeth

Placido Domingo (center) as Macbeth and Ekaterina Semenchuk (left) as Lady Macbeth

Arturo Chacón-Cruz was a poignant Macduff who sang with a lyrical sound and exquisite grace. He seemed surprised by the warm reception his aria garnered. Roberto Tagliavini was an understated Banquo who sang with virile dark tones. Two singers from the Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artists Program, Summer Hassan and Theo Hoffman, were notable for their excellent tonal quality and understandable diction. I hope to hear a great deal more from each of them.

Ekaterina Semenchuk as Lady Macbeth

Ekaterina Semenchuk as Lady Macbeth

The Los Angeles Opera Chorus, led by Grant Gershon, was an integral part of the opera's action as they sang their intriguing harmonies. Director James Conlon, who gave a fascinating per-performance lecture, brought out the myriad abilities of the soloists by always keeping the orchestral volume low while they were singing. When they were silent, Conlon’s most impressive orchestra let loose and showed their huge talents. At Macbeth’s last battle there is a little fugue at which the members of the Los Angeles Opera Orchestra brass section showed that they are all capable soloists. Macbeth is an opera that can be seen from various points of view. This production was from the witches’ perspective and it gave the audience a wonderful evening of entertainment.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Conductor, James Conlon; Director, Darko Tresnjak; Scenic Design, Darko Tresnjak and Colin McGurk; Costume Design, Suttirat Anne Larlarb; Lighting Design, Matthew Richards; Chorus Director, Grant Gershon; Fight Director, Steve Rankin; Climbing Consultant, Daniel Lyons; Macbeth, Plácido Domingo; Lady Macbeth, Ekaterina Semenchuk; Banquo, Roberto Tagliavini; Macduff, Arturo Chacón-Cruz; Malcolm, Josh Wheeker; Lady in Waiting, Summer Hassan; Doctor/First Apparition, Theo Hoffman; Second Apparition, Liv Redpath; Third Apparition, Isaiah Morgan; Valet, Reid Bruton; Assasin, James Martin Schaefer.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/KA1_100.png image_description=Ekaterina Semenchuk (Lady Macbeth) and Placido Domingo (Macbeth) in LA Opera's 2016 production of Verdi's "Macbeth." (Photo: Karen Almond / LA Opera) product=yes product_title=Plácido Domingo as Macbeth, LA Opera product_by=A review by Maria Nockin product_id=Above: Ekaterina Semenchuk (Lady Macbeth) and Placido Domingo (Macbeth)Photos by Karen Almond / LA Opera

September 22, 2016

The Rake’s Progress: an Opera for Our Time

The composer and his duo-librettists based their story on William Hogarth’s eighteenth century paintings and engravings. Stravinsky was living in West Hollywood when he wrote the music. Librettists Auden and Kallman were also in the US at that time.

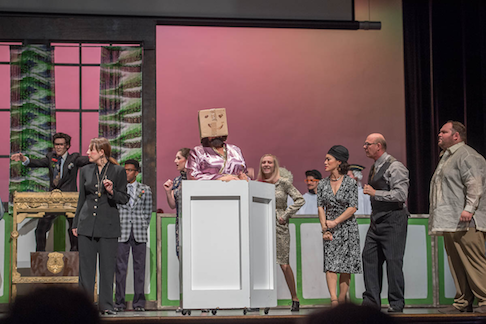

Because The Rake’s Progress requires a chorus and a larger orchestra than POP usually offers, these performances were held at Occidental College, a charming school located in the hills north of Los Angeles. Director Desiree La Vertu guided about a dozen choristers from the college glee club through Stravinsky’s unusual harmonies while POP co-founder and conductor Stephen Karr led twenty-five of the school’s excellent instrumentalists as they accompanied the singers.

POP co-founder, stage director, and designer Josh Shaw updated his show to the 1970s but kept it in England. His simple settings effectively placed the action in the opera's various locales: the Cyprian Queen Pub, Mother Goose's seedy London strip club, Tom’s house, a wildly active auction yard, a cemetery and finally, the day room of the Elysian Fields Asylum. Marie Mawji’s ambient lighting design and Maggie Green’s seventies era costumes helped secure the time and place of each scene.

In Act I, Tom Rakewell works in Father Trulove’s pub along with Anne, but when Nick Shadow tells him he has an inheritance waiting for him in London, he goes off to pursue whatever pleasures the money can buy. In a thoughtless moment, Tom agrees to pay Nick for his services at the end of "a year and a day." Brian Cheney was a sympathetic, clear voiced Tom who—at the beginning—merely wanted a good life for himself and Anne, the girl on whose love he knows he can depend.

Rachele Schmiege was a strong Anne who held her ground both vocally and histrionically. Her aria “No word from Tom” probably brought back memories to a great many audience members who have waited for silent phones to ring. Patrick Blackwell sang Father Trulove with luxurious bass tones that made me want to hear a great deal more of him. Hope POP has him back in a larger part very soon. Adrian Rosas was a wily Nick whose solid voice and unctuous character seemed related to Gounod’s and Boito’s devils. One of the reasons for POP’s popularity is Shaw’s insistence on hiring the best voices available.

Adelaide Sinclair was a loquacious Baba the Turk with a strong voice and a constantly flapping black beard. When Tom dropped a box over her head, the audience had a good laugh and he finally got a chance to complete a sentence. Danielle Marcelle Bond was an alluring bawdyhouse manager, Joel David Balzun a memorable madhouse keeper and Robert Norman a fascinating auctioneer whose minions wheeled him around together with his outsized desk.

In the final scenes, especially the epilogue in which various characters warn listeners, often humorously but sometimes seriously, of the evil that can befall those who look for easy money. The audience could easily draw parallels between the final scene of this opera and that of Mozart’s Don Giovanni.

The artists and craftspeople who make up POP managed to make their work look easy while service people made sure audience members never lacked for creature comforts or glasses of something cool and tasty. A Pacific Opera Project performance is a fine place for a visitor to Los Angeles to relax on a fall afternoon or evening.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Music Director, Stephen Karr; Stage Director and Designer, Josh Shaw; Costumes, Maggie Green; Director of Occidental College Glee Club, Desiree La Vertu; Lighting Designer, Marie Mawji; Tom Rakewell, Brian Cheney; Nick Shadow, Adrian Rosas; Anne Trulove, Rachele Smiege; Father Trulove, Patrick Blackwell; Baba the Turk, Adelaide Sinclair; Sellem, Robert Norman; Mother Goose, Danielle Marcelle Bond; Keeper of the Madhouse, Joel David Balzun.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/rake-Press%205.png

image_description=Photo by Martha Benedict

product=yes

product_title=The Rake’s Progress: an Opera for Our Time

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=All photos by Martha Benedict

Classical Opera: Haydn's La canterina

The principal attraction on this occasion was Haydn’s intermezzo, La canterina (The singer) which Classical Opera have recently performed at the Eisenstadt Haydn Festival.

Opera is not the first genre that comes to mind in connection with Haydn, but the composer wrote (according to Grove) thirty dramatic works for the stage, most of which date from the period when he was in the employ of the Princes Esterházy, whose passion for the stage was evidenced by the daily performances that were arranged in the beautiful 400-seat theatre - equipped with the most advanced technical apparatus - at Esterház castle.

After early essays in opera seria Haydn turned from mythological subjects and tried his hand at the emerging buffo form. La canterina is a farcical tale concerning the double-dealing of would-be singer, Gasparina (Susanna Hurrell), aided by her friend Apollonia (Rachel Kelly) who is disguised as her mother. The two tricksters are renting rooms from the singing teacher Don Pelagio (Robert Murray). They exploit his obvious affection for Gasparina to their advantage, but don’t neglect also to tease the smitten Don Ettore (Kitty Whately). When her two lovers discover her deception, Gasparina plays the old game of feigning a faint and her threats to kill herself expel her lovers’ wrath anger and arouse their compassion. The smelling salts cannot be found, but the scent of their gifts of money and jewellery effect a surprisingly swift recovery - ‘How lovely is the aroma of diamonds’ - and Gasparina is absolved by the self-congratulatory dupes: ‘I forgive your many faults for pity is truly heroic.’

Haydn’s music is graceful and the aria forms show invention and dramatic insight - as when Apollonia’s aria, in which she instructs her protégé in the art of make-up, is interrupted by recitative. This performance was billed as ‘semi-staged’; and, it’s true that, despite the music-stands positioned stage left and right, the cast sang off-the-score and made a lively attempt to bring some individuality and definition to what are essentially commedia stereotypes. But, the end result was limited both by the lack of space offered by the crowded Wigmore Hall platform for choreographic invention and by the rather superficial nature of Haydn’s dramatic gaiety.

Fortunately, the vocal performances more than compensated for any dramatic short-comings. Rachel Kelly’s bright, warm mezzo conveyed Apollonia’s mischievous spirit beneath the simplicity and artlessness of Haydn’s melodic line and the flexible rhythmic sway of her ‘make-up aria’ had a folky nonchalance which was enhanced by perky playing from the flutes and horns. Robert Murray had vivid presence and did a good job of capturing Don Pelagio’s nervousness when he arrives to perform the new aria he has composed for Gasparina, anxiously snatching glances at the score and then, ironically, closing it and singing confidently from memory with affected portentousness. Murray’s tenor was relaxed, with a strong baritonal range, and the melodic ornamentation was delivered with insouciance. In Act 2, the disillusioned Don Pelagio attempts to evict the two women and here Murray sang impressively through the line with an even strength and focus across all registers.

Soprano Susanna Hurrell was superb as Gasparina. Her clear lyric quality and sweet-sounding sighs, allied with plaintive cors anglais, softened the angular piquancy of the melodic line, successfully swaying the affections of her offended lover. And, her inflated wistfulness was matched by her thrilling, sparkling timbre in the more melodramatic passages as Haydn ridicules his seria model, until, ‘tormented and grief-stricken’ she had ‘no more voice left’!

Haydn ends both short acts with a lively finale and Page kept up the urgent momentum at the end of Act 1, aided by scurrying strings in unison (though I did wonder if there was a need for the Orchestra of Classical Opera to re-tune between the two acts, given their brevity). I was impressed by the poise and polish of the continuo playing, especially by the unobtrusive precision of cellist Jonathan Rees’ pithy, vibrato-less punctuation of the secco.

Having recently relished Opera Rara’s Proms performance of Rossini’s Semiramide ( review), I thought I was pretty familiar with the tale; but, no, the Metastasio libretto set by Josef Mysliveček (1737-81) - and also by Porpora, Jommelli, Hasse and Gluck, among others - wanders down some twisting byways.

Nowadays, the Prague native is generally considered only in the context of his friendship with Mozart, who greatly admired the older Czech musician’s work. But, Mysliveček might lay posthumous claim to being one of the most successful opera seria composers of his day, and the four arias - characterised by melodic freshness and rhythmic vitality - from his first opera Semiramide that were presented in the first half of this concert showed why. The opera was performed in Venice just two and a half years after Mysliveček had arrived there, having given up his career as a miller to try his hand as a professional musician.

The back-history is convoluted, but as the opera commences Semiramide, having eloped with an Indian prince Scitalce and then survived his jealousy-fuelled assassination attempt, has just assumed the Assyrian throne, disguised as her son Nino, after the death of her husband the King of Assyria.

Tamiri (Whately), a princess from Bactria, must choose from three suitors who have arrived in Babylon to advance their claims. First up was Murray’s Ircano, a ‘wild and unruly Scythian prince’. Murray exhibited impressive vocal strength and evenness, allied with expressive, vigorous delivery and assured breath control in the long, but fairly bland, lines which convey Ircano’s unjustified overconfidence. Murray felt obliged to indulge in bravura display but it did not consistent come off: the heights attempted in the da capo were somewhat strained and not always secure.

Tamiri is more impressed by Scitalce, though. However, to her exasperation, he refuses her for he has espied Semiramide whom he had previously been duped into believing had been unfaithful. Whately’s tone in ‘Tu mi disprezzi’ was rich and formed a nice counterpoint to the horns. She also coped well with the aria’s flexible tempo, shaping a fluent line from disjointed material. Rachel Kelly’s multi-layered mezzo conveyed Semiramide’s ardour, and she was accompanied by beautifully focused, well-tuned flutes and horns who conjured a pastoral idyll. Kelly had no trouble negotiating the floridity of the da capo repeat, singing with vibrant dynamism. Hurrell displayed admirable agility, fluidity, colour and brightness as Mirteo (the brother of Semiramide, who believes his sister is dead), and produced some stylish trills and cadential ornaments. Her vibrato was dynamic but never distorted the pitch, and Hurrell could also ease naturally into gentler moods too.

Haydn’s Symphony No.34 opened the concert. This is one of Haydn’s lesser known symphonies, but like the productions of Norma that have been rattling around the UK during the last six months, this symphony proves to be like a London bus: you wait for ages, and then several turn up at once. Having enjoyed the BBCSO’s Proms performance under Sakari Oramo ( review), it was good to have an opportunity to hear the work with smaller forces in a more intimate venue than the cavernous RAH. Under Page’s guidance the opening Adagio felt ponderous and weighty - though I also sensed in the pulsing D minor strings, intimations of the opening of Mozart’s future Requiem Mass. The lines did have a flowing continuity, but it was not until the second movement Allegro that the sporadic bursts of energy, striking dynamic contrasts, punchy horn playing and shimmering string tremolos lifted the music above the mundane. The strings running scales were superbly precise and well-coordinated, the clear-edged sound creating a dramatic contrast with the preceding clouded darkness. The Menuet and Trio were cheerfully melodious: the motifs slithered easily, coloured by the occasional faux-ominous semitonal inflection. The whirling strings were countered by sturdy horns in the final Presto assai and the brightness and excellent ensemble of the coda brought things to an impressively unified close.

2017 will see Classical Opera step into 1767, and Mozart ‘take centre stage’. The programme for next year includes stagings ofDie Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebots, which the company recorded in 2013 (review) and Apollo in Hyacinthus, as well as performances with Kristian Bezuidenhout at the Wigmore Hall of Mozart’s first four keyboard concertos.

Claire Seymour

Classical Opera: conductor/artistic director, Ian Page.

Haydn - Symphony No.34 in D minor; Myslivecek - Arias from Semiramide (‘Talor se il vento’, ‘Tu mi disprezzi ingrato’, ‘A pastor se torna’, ‘Fiumicel che s’ode appena’); Haydn - La canterina (semi-staged).

Ailish Tynan (soprano, Gasparina), Rachel Kelly (mezzo-soprano, Apollonia), Kitty Whately (mezzo-soprano, Don Ettore), Robert Murray (tenor, Don Pelagio); Orchestra of Classical Opera.

Wigmore Hall, London; Monday 19th October 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/La_Canterina.png image_description=Classical Opera at the Wigmore Hall product=yes product_title=Classical Opera at the Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=September 21, 2016

Dream of the Red Chamber in San Francisco

The Tutino opera was said to be a co-production with Teatro Regio di Torino though there is no trace of it in upcoming Torino seasons. Dream of the Red Chamber is a co-production with the Hong Kong Arts Festival where it will be performed in English. It is said that if there are additional performances in China Mr. Sheng will re-cast it in Chinese, with the intriguing question of how this English language Gian Carlo Menotti-like theater piece will sound sung in Mandarin.

The Bright Sheng Dream of the Red Chamber is a very Chinese indeed, based on a famous Chinese novel of the same name by one Cao Xueqin of the 18th century Qing Dynasty, his novel considered one of the four pre-modern Chinese classics.

As it came down to those of us sitting in the War Memorial Opera House it is the story of a family who owes the emperor money. The debt can be repaid if the family scion will marry a rich heiress. He however prefers to write poetry with a pretty cousin. He has a dream sleeping in a red chamber in which the two young women appear, confusing him.

Yijie Shi as Bao Yu seized by imperial guards

Yijie Shi as Bao Yu seized by imperial guards

San Francisco Opera’s publicity enthused that this is the Chinese equivalent of Romeo and Juliet, though it really is the equivalent of Richard Strauss’ Die Liebe der Danae, originally titled A Marriage of Convenience.

Unlike the motivic subtleties Richard Strauss exploits, Bright Sheng has based his musical story telling on the tunes of Chinese folk songs, and there are four or five of them that appear and then reappear, one in particular stood out sung to the words “A woman's only chance for happiness is to marry well.”

Mr. Sheng’s style is middle-of-the-road, mid-last-century with strong moments of Stravinsky and Hindemith et al, though there is a strong dose of mid-range brass and jazz chords that adds a big-band feel from time to time. What makes his style unique are the lurid colors of the orchestration, glissandos and oriental intervals. Mr. Sheng is a very able composer, and of prolific invention when expanding his folk song material.

Most characteristic of his vocal lines was the leap of a major 7th to a high note, and there were high notes aplenty, delivered always forte to fortissimo.

Like musical comedy, Mr. Sheng and his famed Chinese-American co-librettist David Henry Hwang (Broadway’s M. Butterfly) set up situations and then sang songs about what had happened. There were lots and lots of songs. It is a very long opera.

A scene from the opera

A scene from the opera

Like musical theater, the sets, designed by Tim Yip (the film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon), were cloth drops that flew in and out and small wagons of set pieces that rolled on and off so that locations could quickly and easily be changed without breaking the pace of the opera’s musical theater song structure. Obviously there was much bright red color, and much richness in the imperial decor that threatened the debtor family. Mr. Yip, an Academy Award winning art director, supplied the costumes as well, of required 18th century Chinese dynastic splendor.

Of note in the large cast was tenor Yijie Shi who brought a fine level of operatic professionalism to his role as the family scion.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Dai Yu: Pureum Jo; Bao Yu: Yijie Shi; Lady Wang: Hyona Kim; Bao Chai: Irene Roberts;

Granny Jia: Qiulin Zhang; Princess Jia: Karen Chia-ling Ho; Aunt Xue: Yanyu Guo; The Monk/Dreamer: Randall Nakano; Lady-in-Waiting/Flower: Toni Marie Palmertree; Lady-in-Waiting/Flower: Amina Edris; Lady-in-Waiting/Flower: Zanda Švēde; Eunuch/Stone:

Pene Pati; Eunuch/Stone: Alex Boyer; Eunuch/Stone: Edward Nelson. San Francisco Chorus and Orchestra. Composer and Co-librettist: Bright Sheng; Co-librettist: David Henry Hwang; Conductor: George Manahan; Stage Director: Stan Lai; Production Designer: Tim Yip; Lighting Designer: Gary Marder; Choreographer: Fang-Yi Sheu. San Francisco War Memorial Opera House, September 18, 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/RedChamber_SF1.png

product=yes

product_title=Dream of the Red Chamber

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: A scene from the opera, Tim Yip designer [All photos by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

San Diego Opera Opens with Recital by Piotr Beczala

Their sold-out presentation was the first performance of this new Shiley Detour Series, which will continue in November with the David T. Little’s new opera Soldier Songs and will return in March with Peter Brook’s The Tragedy of Carmen.

Beczala sang a few songs along with numerous lyric and dramatic arias, pouring forth a feast in Italian, French, German, and Czech for the city’s vocal music connoisseurs. He began with Ruggiero Leoncavallo’s simple serenade, Mattinata, which opened the door to his smooth, lyrical rendition of “Dei miei bollenti spiriti,” from Verdi’s La traviata, and a more dramatic and exciting presentation of “Di’ tu sei fedele” from the same composer’s Un ballo in maschera.

Beczala and Katz followed the Italian selections with Antonin Dvořák’s bittersweet Gypsy Songs and the Prince’s Aria from the same composer’s Rusalka. Although the Czech song texts may not be easily deciphered, the tunes are as familiar as cookies from grandma. Both singing and accompaniment were insightful, sometimes joyous and at other times plaintive. In the Rusalka aria, the Prince has fallen in love with a spirit and even thought he knows his enchanting vision is not real, he begs it not to end. Beczala and Katz continued with a rousing version of Franz Lehar’s “Dein ist mein ganzes Herz” from Das Land des Lachelns and a more introverted interpretation of Richard Strauss’s Cäcilie. I wondered why he did not end the first half of the program with the better-known operetta aria.

The Balboa Theater is not large and San Diego music lovers filled every conceivable seat. Perhaps next time the opera presents an equally important concert, it can be held in a larger hall. This recital was one of the best to be heard in many years. For the second half of the program, Beczala and Katz offered magnificent performances of three French arias: “Pourquoi me reveiller” from Jules Massenet’s Werther,“Ah leve-toi Soleil” from Charles Gounod’s Romeo et Juliette, and The Flower Song from Georges Bizet’s Carmen. Again, Beczala mixed lighter and heavier arias, showing that he could handle both with unusual ease. Few tenors can sing the Flower Song’s high note pianissimo but Beczala sang it the way Bizet wrote it. From this audience of long time operagoers, the applause was almost deafening.

The last group was again Italian, and included the artist’s enchanting delivery “Quando le sere al placido” from Verdi’s Luisa Miller and their captivating depiction of tenor Cavaradossi’s arias from Puccini’s Tosca. They exuded charm in the character’s joyous ode to feminine beauty, “Recondita Armonia” and underscored the tragedy of his realization that he will never again see the stars in the sky in “E lucevan le stelle.” Although some handkerchiefs were evident at the end of this concert, they were soon back in their pockets as the appreciative audience called the artist back and stood to show its admiration for the smiling artists.

Over the last few years, we have not heard Martin Katz in recital very often. He teaches, he conducts, and he edits, but he still has the agility and the artistry to make his mark as a top-level recital collaborator. Beczala and Katz continued with three encores: Italian-born American Salvatore Cardillo’s Core ‘ngrato (Ungrateful Heart), Polish composer Miczyslaw Karlowicz’s Pamietam ciche, jasne, zlote dine (I Remember Quiet, Clear Golden Days), and operetta composer Robert Stolz’s unforgettable “Ob blond ob braun, ich liebe alle Frau'n” from the movie of the same name. That last song with its powerful final high note sent every lady in the theater out with the thought that the tenor appreciated individual beauty. It was a wonderful way to end this exquisite recital. Hopefully Beczala will again appear in Southern California the next time he tours the United States.

Maria Nockin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Piotr_Beczala_Frers.png

image_described=Piotr Beczala [Photo by Anja Frers/DG]

product=yes

product_title=San Diego Opera Opens with Recital by Piotr Beczala

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Piotr Beczala [Photo by Anja Frers/DG]

September 20, 2016

Andrea Chénier at San Francisco Opera

Andrea Chénier is a masterpiece of many styles — of verismo, the micro-second before emotion explodes; of melodramma, the moment emotion is expressible only by singing; of post-Romanticism where emotional colors overwhelm all dramatic impetus. Its libretto is a triumph of latent lyricism that dissolves into a musical magic that possesses your mind, body and soul.

And it all happened on the War Memorial stage. Well almost.

The eight-year so far tenure of San Francisco Opera music director Nicola Luisotti has imposed a resplendent warmth and suppleness to this superb orchestra, attributes that responded most comfortably to the ample tempos the maestro imposed onto Giordano’s opera, tempos that fused easily and naturally with the musical impulses of the singers.

It was this sometimes problematic maestro at his finest, his hyper-Italianate musicality flowing unabashedly and unstoppably for the two hour, too brief duration of this magnificent opera.

Second from left Anna Pirozzi as Maddelena, third from left J'Nai Bridges as Bersi, choristers and supers, Yonghoon Lee as Chénier

Second from left Anna Pirozzi as Maddelena, third from left J'Nai Bridges as Bersi, choristers and supers, Yonghoon Lee as Chénier

Andrea Chénier is a tenor showpiece, and actually little more than that, four gigantic arias that are an exposé of voice and style and pose. It was once whispered in War Memorial corridors that tenorissimo Roberto Alagna would be our Chènier, but even his splendid swagger could not compensate for the uncomfortable phrasing of his 2013 concert attempt at the role (Opera Orchestra of New York). Tenorissimo Jonas Kaufman was the original Chénier of this Covent Garden production brought now to San Francisco, but this oh-so-famous tenor does not find his way to the operatic provinces.

And all the better because San Francisco Opera fielded South Korean tenor Yonghoon Lee as the doomed poet Andreas Chénier. If lacking the ethnicity of the Italian tenor, Mr. Lee’s distilled mastery of the style was exquisite. The vocal gestures were elegant moreso than mannered, the posing more for vocal and musical necessity than tenorial vanity. Mr. Lee’s performance satisfied on every level, he proved himself a connoisseur's tenor.

Yonghoon Lee as Chénier, George Gagnidze as Gérard

Yonghoon Lee as Chénier, George Gagnidze as Gérard

Blue chip casting continued with the Gérard of Georgian baritone George Gagnidze. Famed as a Rigoletto (L.A. and Aix-en-Provence in my experience), Gagnidze finds the deep humanity of this footman infatuated both by the poetry of the revolution and by the beautiful daughter of the soon-to-be annihilated aristocratic family he serves. Beautifully sung and sensitively acted he upheld the artistically aristocratic tenor of the performance.

Outstanding among the fine cast were the charming Bersi of J’Nai Bridges, the confident Roucher (Chénier’s friend) by David Pershall, and the gruff and rough Mathieu (the sans culotte), not to overlook Joel Sorensen’s sly Incroyable. The cameo of the blind Madelon offering her grandson to the revolution was satisfyingly delivered by Jill Grove. Finally much appreciation must be extended to the San Francisco Opera Chorus for the splendid execution of its sizable role in the opera,

Problematic were the performances of Catherine Cook as the Countess of Coigny who made the role broad caricature, a tone that clashed with the overall mood of the opera. The role of Maddalena (daughter of the Countess in love with Chénier) was taken by Italian soprano Anna Pirozzi who sang the notes adequately without evoking either musical or dramatic character. Much reference was made to her golden hair though her wig read as mousy brown (from my seat in Row 16).

The production was by British director David McVicar who stages most everything of size and importance at San Francisco Opera (and the Met and Covent Garden and elsewhere). His productions are well researched, beautifully designed, skillfully executed and always very big (but not too). And entirely generic.

The scenery for this Andrea Chenier was designed by Robert Jones, well known to the world’s major operatic venues. The solid constructions were rich in period detail, creating the very specific environment of late 18th century France. The costumes designed by Jenny Tiramani were rich in period detail, though the white dresses worn by Maddelena and Bersi in the first act (1789 eve-of-Revolution) seemed a bit similar to the white dresses of the merveilleuses (fashionable women who survived the Reign of Terror) of the second act (1794). Hear/tell the costumes were also constructed in period technique (no zippers, only hooks) if not, hopefully, in actual Lyonnaise silk.

As a David McVicar production is haute gamme so was the lighting, a virtuoso accomplishment of lighting designer Adam Silverman who struggled nonetheless to create a sense of mood. The play of lights and shadows remained, like the McVicar production, an exercise in theater technique rather than a dramatic and musical discovery of Giordano’s magnificent opera.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Andrea Chénier: Yonghoon Lee; Maddalena di Coigny: Anna Pirozzi; Carlo Gérard: George Gagnidze; Bersi: J’Nai Bridges; L'Incredibile: Joel Sorensen; Mathieu: Robert Pomakov; Roucher: David Pershall; Madelon: Jill Grove; Contessa di Coigny: Catherine Cook; Pietro Fléville: Edward Nelson; The Abbé: Alex Boyer; Dumas: Brad Walker; Fouquier-Tinville: Matthew Stump; Schmidt: Anthony Reed; Major-Domo: Anders Fröhlich. San Francisco Opera Chorus and Orchestra. Conductor: Nicola Luisotti; Stage Director: David McVicar; Set Designer: Robert Jones; Costume Designer: Jenny Tiramani; Lighting Designer: Adam Silverman. San Francisco War Memorial Opera House, September 17, 2016

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Chenier_SF1.png

product=yes

product_title=Andrea Chénier in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Yonghoon Lee as Chénier, Anna Pirozzi as Maddelena [All photos by Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

September 19, 2016

A rousing I due Foscari at the Concertgebouw

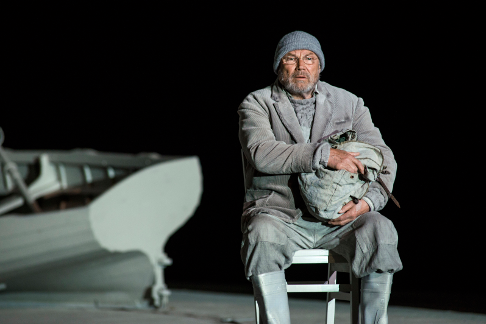

Verdi thought his 1844 opera about a fifteenth-century Venetian Doge torn between political expediency and filial love suffered from persistent gloom. Indeed, apart from a couple of reveler and gondolier choruses, doom and darkness dominate. However, the main shortcoming of the libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, who would collaborate with Verdi on those consummate dramas, Rigoletto and La traviata, is that it introduces the characters in the midst of their predicament and leaves them there until the tragic ending. At the start of the opera Jacopo Foscari is in prison, awaiting trial for the murder of Ermolao Donato, head of the Council of Ten. Donato had had him exiled for conspiring with enemy states. Francesco Foscari, the Doge, believes his son is innocent, but feels constrained to bend to the patricians’ will. Jacopo’s wife, Lucrezia Contarini, fervently and fruitlessly urges him to pardon his son. Jacopo is found guilty, but his execution is mitigated to renewed exile. The Doge’s hope is restored when Donato’s actual murderer confesses the crime on his deathbed, but he then hears that Jacopo has committed suicide on the way to Crete. Having lost the last of his children, the Doge also loses his power when the Council declares him too broken to continue ruling. His heart succumbs and he dies.

The music has a simple but effective transparency and offers several glimpses into Verdi’s future compositions. The Doge’s heartbreaking aria after his son’s sentencing is a precursor of Rigoletto’s anguish for his abducted daughter. A downcast clarinet solo representing Jacopo, here played with silken plangency by Arjan Woudenberg, ends in a trill that reappears in La traviata. Even removed from the context of the composer’s maturation, however, I due Foscari has plenty of merits. Verdi’s gift for translating psychological states into captivating melodies is very much in evidence. The vocal writing is firmly anchored in the first half of the nineteenth century, and conductor Giancarlo Andretta was ever mindful of its technical demands on the singers. He gave them expressive space while maintaining rhythmic tautness. His unfussy, eye-on-the-ball conducting served the music exceedingly well. The Netherlands Radio Philharmonic’s supple playing brought out the score’s ominous melancholy and its evocation of the Venetian waterscape, not least in Ellen Versney’s ravishing harp. Sobbing orchestral rubati intensified the pathos of the final scenes. Equally impressive, the Netherlands Radio Choir clearly differentiated their collective characters as they alternated between dour statesmanly mutterings and carefree barcarolles echoing on the lagoon.

The soloists all brought valuable qualities to this roaringly applauded performance. Verdi mostly uses the supporting cast in the concertato ensembles, yet they all made fine appearances, however brief. Soprano Aylin Sezer displayed a glowing timbre as Lucrezia’s confidante Pisana. Tenor Andrew Owens and bass Giovanni Battista Parodi as, respectively, senator Barbarigo and the Doge’s political rival Loredano, injected all the drama they could muster in their scenes, which are mostly of the “enter a messenger” type. In the Doge’s robes Sebastian Catana was richly sonorous and lyrically introspective. His is not a conventionally beautiful baritone, but it has a firm core and can envelope a concert hall. His Francesco was passive and homogenous of hue in the first two acts. One could argue that this suited a character hobbled by political impotence. Appropriately, Catana saved his most heart-rending singing-acting for Act III, when the Doge crumbles.

As his son Jacopo, Roberto De Biasio had no truck with such inward subtlety. And why should he? He was, after all, the tenor-hero in extremis. De Biasio had reliable high notes and was on sure ground when singing forte. At lower pitch and volume his voice was less responsive and lost power, sometimes disappearing altogether. His instinct for style and theatre, however, compensated for the limited flexibility. He went for broke emotionally and won the audience over, shaking the thunder sheet when Jacopo is beset by horrific hallucinations and singing a stirring farewell to his wife. Tamara Wilson had temperament and voice in spades for the impassioned Lucrezia. Apart from less than ideally defined trills and sustained high notes occasionally tapering into shrillness, Wilson’s performance was dazzlingly secure. As malleable as her soprano sounded in the cavatinas, she had even more control in the raging cabalettas, skimming gracefully op and down scales and firing full-voiced high B flats and pointed high Cs. Lucrezia is a two-mood character — she is either angry or miserable. Working within these limits, Wilson managed to add poignant shading to the grand gestures. Her interrogative diminuendo on the words “mio prence” (my prince) when greeting her freshly deposed father-in-law, for example, contained a world of compassion. It was a bravura performance with plenty of heart.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and other performers:

Francesco Foscari: Sebastian Catana; Jacopo Foscari: Roberto De Biasio; Lucrezia Contarini: Tamara Wilson; Jacopo Loredano: Giovanni Battista Parodi; Barbarigo: Andrew Owens; Pisana: Aylin Sezer; Attendant on the Council of Ten: Mark Omvlee; Servant of the Doge: Lars Terray. Netherlands Radio Choir, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic. Conductor: Giancarlo Andretta. Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, Saturday, 17th September 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/FrancescoFoscariBastiani.png image_description=Francesco Foscari, by Lazzaro Bastiani [Source: Wikipedia] product=yes product_title=A rousing I due Foscari at the Concertgebouw product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=Above: Francesco Foscari, by Lazzaro Bastiani [Source: Wikipedia]September 17, 2016

A double dose of Don Quixote at the Wigmore Hall

In this well-balanced, entertaining programme at the Wigmore Hall, the English Concert under their director Harry Bicket celebrated the 400th anniversary of the Spanish writer’s death with musical accounts of Quixote’s anarchic fantasy dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Thomas D’Urfey’s extravagant dramatic adaption of Cervantes’ novel was originally presented as three separate plays, lasting seven hours in total, at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane in 1694. Music was a standard addition to Restoration spoken drama and on this occasion Purcell provided the lion’s share with John Eccles and other less well-known composers contributing further songs and entr’actes. Selected songs were subsequently published, but the complete music from Don Quixote was never collected together and much of the instrumental and dance music is now lost. However, almost all of the songs have survived, and the English Concert presented some of those by Purcell which are included in the posthumous tribute to the composer, Orpheus Britannicus, interspersed with instrumental music from The Married Beau, another of the Theatre Royal’s 1694 productions.

Bass Matthew Brook showed real showmanship in his two arias: he relished Purcell’s earthy theatricality, every word was crystal clear and his bass retained beauty of tone even in the moments of exaggerated musical and dramatic bravura. ‘When the World First Knew Creation’ is sung by a galley slave, Gines de Passamonte, to thank Quixote for releasing him and his fellow criminals from imprisoned servitude. Brook remained poker-faced through this ode to his Redeemer - ‘When the word first knew Creation/ A Rogue was a top Profession;/ When there were no more in Nature but Four,/ There were Two of them in Transgression’ - relishing the pithy rhymes and letting his characterful bass convey the irony. ‘Let the Dreadful Engines of Eternal Will’, in which misguided Cardenio expresses his misery that his beloved Luscinda has abandoned him, was a tour de force of vocal rhetoric. Brook showed impressive flexibility in the florid madrigalianisms - ‘Within my Breat far greater Tempests grow’ - and the declamatory passages were imperious: ‘Ye pow’rs, I did but use her Name,/ And see how all the Meteors flame.’

Brook moved slickly between passions. The lowest reaches of his bass conveyed profound solemnity: ‘And now the Globe more fiercely burns,/ Than one at Phaeton’s Fall. There was touching melancholy in his lament, ‘Ah! where are now those Flow’ry Groves,/ Where Zephir’s fragrant Winds did play?’, complemented by an eloquent cello counter-melody and mournful lute. Then, anger vivified his grievance, ‘I glow, I glow, but ‘tis with hate:/ Why must I burn for this Ingrate?’ From vengeful resonance, Brook retreated to blanched despair: ‘Cool, cool it then and rail,/ Since nothing will prevail.’ Gesture, facial expression and posture all contributed to an utterly convincing account, and Brook’s eyebrows worked as hard as his voice to capture the caustic mockery of music and text: ‘And so I fairly bid ’em, and the World,/ Good Night.’

Anna Devin has a full-bodied soprano but at the start of ‘From Rosie Bower, where sleeps the God of Love’ there was a slightly harsh edge to the tone and the diction was unclear. The scene depicts Altisidora’s jealous Don Quixote as he is going to bed, feigning insanity in the face of his rejection of her love in favour of the Princess Dulcinea. With agility and athleticism Devin negotiated the vocal line’s large leaps of the first section of the five-part air, to the accompaniment of luthier William Carter, and enjoyed the rhythmic robustness of the following dance - ‘With a Hope and a Bound/ And a Frisk from the Ground,/ I’ll trip, trip like a Fairy’ - as Altisidora seeks to out-pirouette the dainty Dulcinea. In the recitative that followed, Devin’s soprano relaxed and her fears that ‘Ah! tis in vain’ were persuasively dramatic. She further demonstrated that she could shift smoothly through the changes of emotional-gear in the final sections, culminating with the extravagant avowal, ‘A thousand Deaths I’ll die,/ E’re thus in vain adore’.

Brook and Devin came together for the final number, ‘Since Times are so bad’, in which, returning to their home town, they are duped by the Duke that Dulcinea has been bewitched and that her release from enchantment depends on Sancho Panza subjecting himself to 3000 lashes, after which he will become Governor of the island of Barataria! The lure of social elevation inspire his wife and a Clown to song, and both singers entered vigorously into the spirit of the characters’ foolish but heady hopes for ambition and advancement.

The instrumental interludes were similarly spirited, with vibrant bow strokes bring the first Aire to life and the second Hornpipe fizzing excitedly. The Jigg was airy and light, and contrasted with a trumpet-less but resonant ‘Trumpet Air’ in which the energised bass line of Joseph Crouch and Jonathan Byers (cello) and Christine Sticher (double bass) added depth and dynamism.

Telemann’s Suite burlesque de Don Quichotte is a lively instrumental account of the penniless nobleman’s deluded adventuring. A ‘tone poem’ to rival Till Eulenspiegel, Quixote’s merry mishaps are vivaciously depicted and the diversity of colour and texture of Telemann’s characterful movements emphasises the chasm between the chivalric romancer’s fanciful imagination and humdrum reality.

The members of the English Concert made good story-tellers, drawing listeners into the narrative with an assertive Overture whose cadences were richly double-stopped and rhetorical in tone. The strings revealed their tender side in ‘Le Réveil de Quichotte’, their compound-time lilt gently nudging the knight from his dreams; then, a solo quartet’s sweet sighs nestled quietly beneath Danann McAleer’s decorously restrained narration, conveying Quixote’s deluded love for Princess Dulcinea. This was truly lovely playing by leader Nadia Zwiener, whose ornamentation was idiomatic and refined. A furious attack on ‘les moulin à vent’ showcased the group’s superb ensemble and precision, and bows flew vigorously in sweeping surges as Sancho Panza was tossed in a blanket for his master’s sins, after the latter had crept from an inn without paying his host for his hospitality. An erratic minuet represented the lurching canter of the Don’s exhausted horse, Rocinante - all lopsided accents and dynamic contrasts - followed by a more agile and fluid trio section, and the Suite closed with Quixote’s fitful dreams, ‘Le couché de Quichotte’, a light-fingered romp suggestive of the deluded Don’s heroic wishful thinking.

McAleer, seated centre, steered us beguilingly through the musical narrative, but one couldn’t help feeling that Telemann had done the work for him.

This was a performance of real vitality and freshness. There was much humour, both ribald and affectionate, but honesty and warmth too. An evening of delightful joie de vivre and high-spirited élan of which the fictional hidalgo would certainly have approved.

Claire Seymour

Henry Purcell: Suite - The Comical History of Don Quixote Z578 (excerpts) including incidental music from The Married Beau Suite Z603; Georg Phillipp Telemann: Ouverture-Suite - Burlesque de Quixotte TWV55:G10

The English Concert: Harry Bicket (director, harpsichord), Anna Devin (soprano), Matthew Brook (bass-baritone), Danann McAleer (narrator).

Wigmore Hall, London; Wednesday 14th September 2016.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Matthew_Brook_-_photo_credit_Richard_Shymansky.png image_description=The English Concert at the Wigmore Hall product=yes product_title=The English Concert at the Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Matthew BrookPhoto credit: Richard Shymansky

September 15, 2016

Bampton Classical Opera: A double bill of divine comedies

With characteristic ingenuity and wit, the company presented two little-known but musically rewarding operas, each under an hour in length, in which meetings between mortals and deities give rise to conflict and confusion but conclude, inevitably, with Love triumphant. Bampton director Jeremy Gray has treated these classical allegories with a healthy dose of insouciance. And, with so much to-ing and fro-ing between earthly and celestial realms, where better to set the action than a terrestrial portal - an airport arrivals lounge - and an airplane in transit to the heavens. At Bampton in July, RAF Brize Norton had contributed some all too realistic supplementary sound effects, but we were safe from unscheduled flypasts inside St John’s and the Corinthian columns of the nave provided an appropriately classical ambience.

Gluck composed Philémon e Baucis in 1769 for the extended festivities which accompanied the marriage of his long-term Hapsburg employer Ferdinand, Duke of Parma (who was the grandson of Louis XV of France) and Maria Amalia, Archduchess of Austria, the sister of Marie Antoinette. The myth tells of two young lovers, the eponymous shepherd and shepherdess, who show great respect and care for the god Jupiter when he appears before them disguised as a pilgrim. In return, the rustic couple are blessed by Jupiter with everlasting life and elevated to the status of demigods. At the same time, he curses their fellow Phrygians who had refused to help him.

Catherine Backhouse (Philemon) and Barbara Cole Walton (Baucis). Photo Credit: Jeremy Gray.

Catherine Backhouse (Philemon) and Barbara Cole Walton (Baucis). Photo Credit: Jeremy Gray.

In Gray’s neat and natty production, Philemon (mezzo Catherine Backhouse) and Baucis (soprano Barbara Cole Walton) have cast aside their shepherds’ smocks and crooks for an immigration officer’s uniform and cleaner’s mop respectively. Last through customs is a scruffy, irascible Jupiter (tenor Christopher Turner) who wastes no time in making clear his displeasure at having to travel in economy, and his disgruntlement with the failure of Arne Airways (‘the low-cost airline - no frills, plenty of trills!’) to offer him some complementary champagne.

Fortunately, the musical musings of the two lovers are sufficiently dulcet to sweeten the tetchy deity’s mood - he is even inspired by Philemon’s melodious strain to take up his guitar and strum a gentle accompaniment - and tea and biscuits prove an effective substitute for Dom Perignon.

Backhouse’s mezzo was rich and vibrant, full of character and expressively phrased. It’s a lovely clean sound and blended perfectly with Cole Walton’s crystalline soprano in the roulades of thirds and sixths which spun deliciously in their duets. Both singers acted well: their joyful smiles and affectionate teasing conveyed an innocent wonder that they had been so lucky in love. And, Cole Walton wowed in her florid coloratura aria, ‘You are my shepherd and lover’, by climbing to heights which I had thought were beyond the reach of human voice (top G?). She leapt and glided into dog whistle territory without the slightest hint of strain, as if propelled ever higher by infinite ardour and delight; the intonation was spot on and the tone pleasing as she slithered and curled back down again. Stunning!

Christopher Turner as Jupiter. Photo Credit: Jeremy Gray.

Christopher Turner as Jupiter. Photo Credit: Jeremy Gray.

Christopher Turner was fittingly snappish and petulant as the peeved god, but puffed up proudly with gilded self-importance when revealing his true identity to the lesser mortals. Turner’s tenor is a versatile instrument and his diction was excellent (though we were, helpfully, given a copy of Gilly French’s pithy translation).

Bampton’s trademark visual gags and irony were present in abundance. An air-traffic controller in high-vis vest semaphored the plane across the runway to the overture’s perky rhythms. A sign warned against sleeping in the multi-faith chapel before the latter was transformed by Jupiter into a ‘Templvm’; giant Toblerones grabbed from the duty-free shop by the returning travellers’ chorus (soprano Aoife O’Sullivan, tenor Robert Anthony Gardiner and baritone Robert Gildon) formed a perfect nuptial arch to frame the married couple. Turner’s impressively authoritative aria di furia prompted a clamorous storm sequence and both raging god and thunder were calmed only after extensive, robust fanning, umbrella twirling and a cooling spray from a fire-extinguisher. There was some minor ‘funny business’ and mime during the instrumental episodes which did not feel entirely natural or necessary, but I suppose there was a need to invent ‘activity’ to keep the visual drama running.

Christopher Turner (Jupiter) and Aoife O’Sullivan (Chorus soprano). Photo Credit: Jeremy Gray.

Christopher Turner (Jupiter) and Aoife O’Sullivan (Chorus soprano). Photo Credit: Jeremy Gray.

Thomas Arne’s The Judgment of Paris, which Bampton first performed during the 2010-11 season was first performed in London on 12 March 1742, and it has been suggested that it may have been intended to upstage Sammartini, the protégé of Frederick the Prince of Wales, for the Italian’s own The Judgment of Paris had been performed at Cliveden in 1740 alongside Arne’s masque, Alfred.

William Congreve’s droll libretto relates the episode in which Paris, a shepherd, is obliged to choose the fairest among the three goddesses, Juno, Pallas and Venus. During the competition, Paris finds himself the subject of various enticements as the goddesses attempt to persuade him in turn to award them the symbol of victory, a golden apple. Far from displaying bucolic gaucheness, Paris demonstrates unanticipated wile in delaying his judgement for long enough to incite the impatient goddess into singing several arias and engaging in a degree of disrobing. Just how is a director to treat Paris’s line, ‘When each is undrest, I’ll judge of the best’?

Demoted from omniscience to mortality, Turner again impressed as the vacillating protagonist who - clearly a flying-phobic - was escorted through security by a smooth-voiced Mercury (Robert Anthony Gardiner), an Arne Air pilot, and charged with the task of deciding which of the three air hostesses deserved the prize - a golden i-Apple. The cast relished the easy melodiousness of Arne’s vocal lines and at St John’s I was able to appreciate even more than in the open-air acoustic at Bampton the instrumental invention evident in the accompaniments, which are often quite light in texture and make beguiling use of obliggato instruments. There was some fine playing by the members of CHROMA, by turns animated and expressive, always lucid. Paul Wingfield conducted with alertness and sensitivity - all the more impressive given that he couldn’t actually see his singers.

Catherine Backhouse (Pallas), Barbara Cole Walton (Juno) and Aoife O’Sullivan (Venus). Photo Credit: Jeremy Gray.

Catherine Backhouse (Pallas), Barbara Cole Walton (Juno) and Aoife O’Sullivan (Venus). Photo Credit: Jeremy Gray.

Soprano Aoife O’Sullivan was excellent as the lewd and lustful Venus. The fact that O’Sullivan is seven-months pregnant added a further dash of drollery; and it perhaps wasn’t fanciful to imagine that the hormones also furnished her wonderfully glossy soprano with even more shine. O’Sullivan produced an easy, full tone, and the high-lying lines were attractive of tone and purposefully shaped. When Venus’s charming aria, ‘Stay, lovely Youth’, enticed the bewildered Paris into the passenger toilet, the rival hostesses knew all was lost.

Movement director Triona Adams and Gray have crafted some waggish and witty routines. Who knew that aircraft safety paraphernalia - seat-belts, whistles, life jackets and the like - had such erotic potential? Paris’s air-sickness during the storm whipped up by Pallas’s musical call-to-arms suggested that perhaps he wasn’t cut out to be a hero after all.