June 27, 2017

Kathleen Ferrier Remembered

Bruno Walter accompanies Ferrier in two Schubert and two Brahms songs. Walter was a major influence on Ferrier, developing her style and repertoire and bring her to international prominence. Reputedly, she was so overcome rehearsing for Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde that she wept inconsolably. Perhaps it was that emotional directness that Walter recognized that convinced him that the relatively unknown young singer had potential. In these songs, recorded in the Edinburgh studios of the BBC, Ferrier's sincerity shines, though her delivery is more enthusiastic than refined. But that was part of her charm. Walter responds in kind, his playing particularly free and invigorating.

Ferrier's recordings of Mahler's Rückert Lieder and Kindertotenlieder are classics, but on this disc, she sings Urlicht, from Mahler's Symphony no 2. in the version for voice and piano. This recording was made on 28th September 1950. The following year, Ferrier sang the part with full orchestra in the recording of the symphony with Otto Klemperer and Jo Vincent in Amsterdam. The closer focus of this version concentrates attention on the voice and its distinctive colouring. Ferrier's vibrato is used to evoke fragility, in keeping with the nature of the piece. A worthwhile addition to the discography, since she didn't record this version for Decca. This recording predates the Christa Ludwig recording of this version of Urlicht by 13 years.

Apart from one track on this disc - C Hubert Parry's Love is a bable op 152/3 with Gerald Moore - all the other selections feature Ferrier with Frederick Stone. Ferrier sang a lot of Schubert and Wolf, her contralto richness is most effective in Brahms. Her Sonntag op 47/3 here, recorded in December 1949, is particularly impressive. Although Ferrier found fame, she was, at heart, down-to-earth and unaffected, rather like the "Das tausendschöne Jungfräulein" standing by her doorway, innocently capturing hearts. For this reason, perhaps, Ferrier is often most endearing when she sings traditional songs in the English language. This remastering makes Parry's Love is a Bable bright and shiny!

On this SOMM disc, we have Edmund Rubbra's Three Psalms op 61, which Ferrier recorded for Decca with Ernest Lush, in performance with Frederick Stone, from 1947. The piano settings are minimal, displaying the voice unadorned, suggesting private prayer. In Psalm 150, Rubbra writes extravagant lines, which let Ferrier's voice fly exuberantly free. SOMM has also uncovered a special rarity: Maurice Jacobson's Song of Songs, quite probably the original recording, which has lain in the BBC sound archives long known but hitherto unreleased. The text comes from the Book of Solomon, and the setting makes clear reference to Jewish tradition.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/SOMMCD264-cover-Naxos-1024x1024.png

image_description=Kathleen Ferrier Remembered

product=yes

product_title=Kathleen Ferrier Remembered

product_by=SOMM Recordings

product_id=SOMMCD 264 [CD]

price=$16.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?ordertag=Perfrecom26738-2248248&album_id=2253572

Saint Louis Butterfly Soars

That is not to say there weren’t some distinctive touches. But here was a tradition-honoring, dramatically safe production of an evergreen classic that was first of all cast from strength. Cio-Cio San is a “big sing” and Rena Harms proved more than up to the task.

This, in spite of the fact that Ms. Harms was announced as indisposed with allergies. Since Cio-Cio San begins singing offstage, there is an especial emphasis on her voice alone, and owing to the circumstances, the first impression was that it was a bit guarded. Once she entered, we were able to observe that Rena is physically ‘right’ for the role, able to suggest a waif-like fifteen-year-old. In Act One, it seemed that she might be pacing herself, and her limpid soprano was prone to a slight flutter. That could also be owing to her affectation of innocence and naiveté.

Beginning in Act II, Ms. Harms really began to rally and go from strength to strength. Un bel di was touching and full voiced, and a spinto sheen began to evidence itself. Act III evolved into a no holds barred finale, with the diva hurling out full-throated, impassioned phrases that thrilled the ears and stirred the heart. The totality of her achievement was overwhelming, and the audience rose to their feet as one to laud her with an especially vociferous ovation.

(L to R) Michael Brandenburg as B.F. Pinkerton, Christopher Magiera as Sharpless and John McVeigh as Goro

(L to R) Michael Brandenburg as B.F. Pinkerton, Christopher Magiera as Sharpless and John McVeigh as Goro

Michael Brandenburg was a smarmy, self-interested Pinkerton, nevertheless tall and handsome with a clear, muscular tenor. When he wasn’t ringing out over the full orchestra, he caressed his phony protestations of love with honeyed faux conviction. He also injected a tone of characterful cynicism into his early scenes that indelibly defined him as one of opera’s biggest cads.

It was wonderful to hear Christopher Magiera again. His mellifluous, burnished baritone has taken on new weight since last I heard him, and he brought gravity and a sympathetic, bungled paternalistic concern to Sharpless. Mr. Magiera’s assured presence and luminous vocalizing were one of the evening’s great strengths. Renée Rapier was also luxury casting as a potent Suzuki. Ms. Rapier's plummy mezzo radiated authority and her poised singing was a perfect partner for Ms. Harms, the two melding beautifully in their duet.

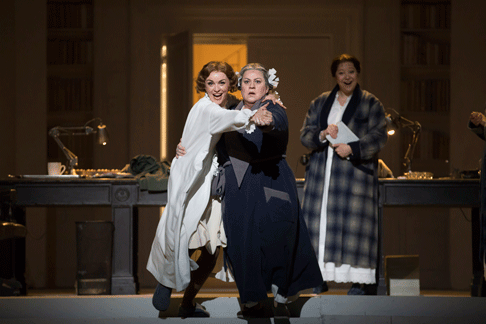

(L to R) Rena Harms as Cio-Cio-San, Sam Holder as Sorrow, and Renee Rapier as Suzuki

(L to R) Rena Harms as Cio-Cio-San, Sam Holder as Sorrow, and Renee Rapier as Suzuki

John McVeigh has a striking lyric tenor voice, but here he effectively subdued its polish to make Goro a mean-spirited, manipulative moneygrubber. Matthew Stump was an imposing, firm-voiced Bonze; Benjamin Taylor a somewhat stoic, though beautifully sung Prince Yamadori; and as Kate Pinkerton, Anush Avetisyan’s distinctive soprano contributed a pleasantly contrasting vocal quality.

In spite of the director’s program notes, Robin Guarino did not seem to re-define the roles of the three named women characters as much as she aspired. What Ms. Guarino did achieve was a cornucopia of effective business that helped define the established characters, as well as developing illuminative subtext that allowed them occasionally interact in fresh ways. She devised effective stage pictures and well-motivated movement, although the love duet curiously reverted to rather stock pairing poses.

Laura Jellinek’s set design was well considered, the upstage mountain appearing to be made of an origami collage. The house was positioned on a turntable to be able to suggest the “public” and “private” life of the heroine. This worked better at some times than others, and the long, flat structure got visually tiresome after a while. Too, there were times that it was turned and slightly angled to no real effect. Still, the suicide “inside” the house, followed by the revolve to allow Butterfly to stagger out the “public” side of the house superbly underscored the final effect.

Candice Donnelly devised and assembled a splashy, colorful set of costumes for the wedding, as well as more subtle, subdued garb for the principals. Tom Watson’s lovely, comprehensive wig and make-up design was notable for a tasteful lack of clichés. Christopher Akerlind’s reliable lighting provided the finishing touches to the look of the production.

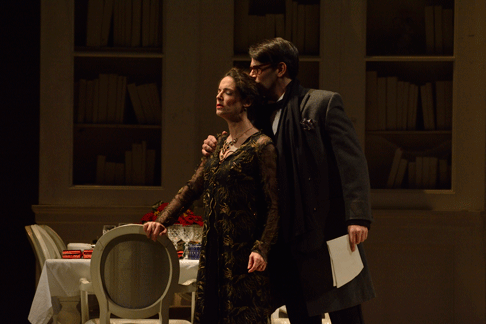

Anush Avetisyan as Kate Pinkerton and Michael Brandenburg as B.F. Pinkerton

Anush Avetisyan as Kate Pinkerton and Michael Brandenburg as B.F. Pinkerton

Michael Christie started off like gangbusters in the opening fugue, with a crackling downbeat. His urgent, breathless beginning soon mellowed out, and by the time we got to the expansive love duet, the Maestro’s pendulum seemed to have swung to the more languid realm. Whatever the tempi, Mr. Christie clearly knew what he wanted, and boy, did he get it! In the small Loretto Hilton theatre, the full scope of Puccini’s orchestral colors had a stunning immediacy, and his partnering with the singers was impeccable. Cary John Franklin’s chorus performed with its accustomed distinction.

In total, OTSL lovingly served up this timeless classic with an accessible translation, top tier talent, and conviction in a fool-proof formula that allowed Madame Butterfly to be a soaring achievement.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Pinkerton: Michael Brandenburg; Goro: John McVeigh; Suzuki: Renée Rapier; Sharpless: Christopher Magiera; Cio-Cio San: Rena Harms; Cousin: Andrea Núñez; Mother: Caitlin Redding; Uncle Yakuside: Dominik Belavy; Aunt: Stephanie Tritchew; Imperial Commissioner: Phillip Lopez; Office Registrar: Benjamin Dickerson; Bonze: Matthew Stump; Prince Yamadori: Benjamin Taylor; Kate Pnkerton: Anush Avetisyan; Conductor: Michael Christie; Director: Robin Guarino; Set Design: Laura Jellinek; Costume Design: Candice Donnelly; Lighting Design: Christopher Akerlind; Wig and Make-up Design: Tom Watson; Chorus Master: Cary John Franklin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BFLY_3318a.png

image_description=Rena Harms as Cio-Cio-San and Michael Brandenburg as B.F. Pinkerton [Photo by Ken Howard]

product=yes

product_title=Saint Louis Butterfly Soars

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Rena Harms as Cio-Cio-San and Michael Brandenburg as B.F. Pinkerton [Photos by Ken Howard]

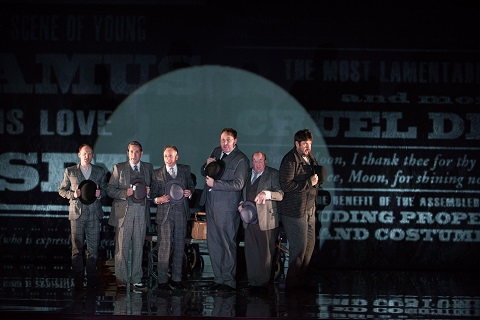

Saint Louis: Gordon’s Revised Grapes

Not a festival goes by that OTSL does not present a world premiere, U.S. premiere, or an important second look at a recent notable composition, in this case Ricky Ian Gordon and Michael Korie’s The Grapes of Wrath.

Based on the celebrated Steinbeck novel, the sprawling masterpiece would seem difficult to tame. The Tony-winning play version produced by Steppenwolf Theatre Company succeeded, but even without music the show was overlong and occasionally hard to follow. The risk seems to be in trying to include too much.

Gordon’s Grapes premiered at Minnesota Opera in 2007 in a lengthy three-act version. In the intervening years, the creators have tightened the narrative considerably. The current two-act version distills the story to all the big moments strung skillfully together with well-defined character relationships and spare, meaningful dialogue. Thrilling choral moments lend an epic, almost cinematic sweep to the piece, elevating and ennobling the human suffering of the humble characters.

Tobias Greenhalgh as Tom Joad and Katharine Goeldner as Ma Joad

Tobias Greenhalgh as Tom Joad and Katharine Goeldner as Ma Joad

Mr. Gordon’s evocative, sometimes eclectic score is inspired by many another composer’s sound palette, including Copland, Bernstein, and Sondheim. Indeed some of the jauntier, folksier numbers recalled a miners’ number from Sondheim’s recent musical about the Meizner Brothers. (Or is it vice versa?) But no matter, Gordon has amalgamated these divergent influences and made this score sing with his own voice, thank-you-very-much. Orchestral writing is in turn varied, atmospheric, soaring, pulsating and colorful, and the vocal lines are grateful and illuminative of the characters’ outward plight as well as their inner feelings.

James Robinson has no equal when it comes to directing such sprawling, episodic contemporary works, and he has once again covered himself in glory as he drew the large ensemble into constant focus even as scenes and situations were in constant flux. When the action settled into an introspective aria, or a sensitive duet, Mr. Robinson deftly framed the moment to create a successive string of pearly ‘set pieces’ even as he preserved the forward motion of the narrative.

Set Designer Allen Moyer has provided an omnipresent soup kitchen as an overall metaphor, an environment in which all the various locales are suggested. As the audience enters the theatre, much of the cast is seated at tables in a parish hall, others loiter and converse in various groupings. A stage with US flag and red grand drape such as is often found in such venues, is up center. As the focal point, this platform is continuously re-dressed effectively to support many imaginative effects.

The cast constantly moves furniture and set pieces about with choreographed precision. At first, I wasn’t sure I was going to enjoy this rustic approach, and the first few scenes did not give me a good sense of time and place. I was won over in very short order, largely owing to the nonpareil lighting design by Christopher Akerlind.

(Center) Tobias Greenhalgh as Tom Joad

(Center) Tobias Greenhalgh as Tom Joad

If I haven’t ever said before that Mr. Akerlind is a company treasure, I should have. His arsenal of effects was the beating heart of the physical production. To name just one heartrending visual: When slow-witted son Noah decides to drown himself to rid his family of the burden to feed him, he first “wades” in wash buckets lit from within. A large white cloth swoops in to cover him as he climbs on the platform. The cloth rises in front of him, and an intense blue spot backlights him as he ‘drowns’ as a floating shadow. All this is complemented by Ma Joad in an isolated special down right, sitting in a rocker with the infant Noah in her arms, a flashback to when she crooned him to sleep not that long ago. So searing, so simple, so profound.

Over the years, costume designer James Schuette has often dazzled us with attire of ravishing beauty. Here, he engaged us with a panoply of earthy, practical period street wear, work clothes and uniforms that aptly communicated the characters’ station in life. Is there room for a company to have two “treasures”? Hell, yes.

In the pit, Conductor Christopher Allen ruled with a sure hand and a full heart, wringing passion and pathos out of his musicians in equal measure. Maestro Allen not only embraced the sweeping cinematic phrases, he also injected sass and wit into the folk-like sections. Best, he managed to support and propel the soloists as they strove unrestrained to reach the emotional jugular in their arias and confrontations. He expertly shepherded the opera’s immense forces, including Cory John Franklin’s meticulously prepared chorus.

In the afore-mentioned Broadway play version of Grapes, Tom Joad got the last star bow. Here, Ma Joad was given that honor. It is easy to see why. While the piece is Tom’s journey (and he has one of the most famous inspirational speeches in all literature), Gordon, Korie, and Robinson have clearly made Ma the guiding force and (pace Steinbeck) I am convinced they are right.

Nathaniel Mahone as The Boy in the Barn

Nathaniel Mahone as The Boy in the Barn

This role was such a perfect fit for Katharine Goeldener’s interpretive gifts, it is hard to know where Ms. Goeldener ended and Ma Joad began. Her Earth Mother presence swept all before it, barking orders one moment, comforting the sick another, healing the hurt as needed, and above all, trying to claw the family together with finger tips of steel. Here is a skilled vocalist with a sound technique who knows what her large, pointed mezzo-soprano can (and can’t) do. She takes some thrilling risks, pushing the voice for dramatic effect, and the results are often electrifying. But Katharine can also draw you in with sustained, floated pianissimi, so private and delicate that she breaks your heart. It is not often we are privileged to witness such a perfect marriage of artist and role.

In the same league, Tom Joad might have been written for baritone Tobias Greenhalgh, who dispatches the rangy role with solid commitment and vibrant vocalization. Mr. Greenhalgh has power to spare, but I did wonder if some of the role’s middle voice passages might not be too densely scored, especially if the piece were given in a larger house. Tobias’ sincere acting, handsome presence, pointed diction and strikingly rich voice made for a powerful impression, none more so than in his memorably sung I’ll be there aria.

Deanna Breiwick was an enchanting presence as Rosasharn. Her secure, silvery soprano floats effortlessly above the staff (and everywhere else, for that matter), and her slight physique and poised singing make her totally believable as the love struck, pregnant young wife. She infuses the opera’s final moments with such heart and hope and humanity that the tears I had been fighting for about the last twenty minutes came flooding like the ravaging rainstorm onstage.

As the Paterfamilias, Levi Hernandez brought tragic authority to Pa Joad, his rolling baritone a comforting presence. Geoffrey Agpalo creates another deeply affecting impersonation as Jim Casy, a former preacher with cheeky observations about life and living. His delectable lyric tenor was suavely deployed, and his opening aria accompanying himself on ukulele was a highlight. Andrew Lovato made the most of his stage time with a neatly sung Connie Rivers, Rosasharn’s restless husband. Mr. Lovato and Ms. Breiwick’s two duets were beautifully rendered, their effortless youthful timbres blending seamlessly.

Michael Day’s petulant Al Joad was wiry in demeanor, but smoothly sung with an assured, honeyed tenor. The waitress Mae has the most musical comedy-like aria with her humorous commentary on truckers and tipping, and Jennifer Panara delivered it with panache and a gleaming mezzo. Veteran Robert Orth used his experience and sometimes, sheer force of will to limn a memorable portrait of the crusty drunkard Uncle John.

Truth to tell, there was really no vocalist who did not excel in the many assignments they essayed. Please read the cast list below and know that each and everyone of them gets a personal bravo from me.

With this performance of The Grapes of Wrath, which closed the 2017 festival, I mused that this year’s four operas were perhaps the finest collection of my many OTSL experiences. While this will be a hard act to follow, I already can’t wait for what comes next.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Rosasharn: Deanna Breiwick; Ma Joad: Katharine Goeldner; Pa Joad: Levi Hernandez; Uncle John: Robert Orth; Connie Rivers: Andrew Lovato; Ruthie: Hannah Dishman; Winfield: Devin A. Best; Noah Joad: Hugh Russell; Al Joad: Michael Day; Tom Joad: Tobias Greenhalgh; Jim Casy: Geoffrey Agpalo; Pete Fowler: Michael Miller; Joe/Pump Guy 1: Evan Bravos; Fred/Pump Guy 2: Samuel Weiser; Hank/Lou: Matthew Dalen; Oklahoma Senator: Daevyd Pepper; Mulley’s Wife: Megan Callahan; Gramma: MaryAnn McCormick; Man in Suit/Agricultural Inspector: Alex Rosen; Constable/Trucker Joe: Dominik Belavy; Traffic Cop/Peach Checker: Phillip Lopez; Trucker/Striker Jim: Jeff Byrnes; Pump Guy 3: Matthew Swensen; Mae: Jennifer Panara; Val: Alexander McKissick; Trucker Bill/Commissary Clerk: Benjamin Dickerson; Cropper Woman/Hooverville Squatter: Nicolette Book; Cropper Husband/Washroom Guard/Vigilante George: Robert Stahley; Deputy: Rafael Helbig-Kostka; Cabin Mistress: Simona Genga; Striker Jake: Philippe L’Esperance; Soprano: Erica Petrocelli; Boy in Barn: Nathaniel Mahone; Conductor: Christopher Allen; Director: James Robinson; Set Design: Allen Moyer; Costume Design: James Schuette; Lighting Design: Christopher Akerlind; Wig and Make-up Design: Tom Watson; Chorus Master: Cory John Franklin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/GOR_0576a.png

image_description=The Joad Family [Photo by Ken Howard]

product=yes

product_title=Saint Louis: Gordon’s Revised Grapes

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: The Joad Family [Photos by Ken Howard]

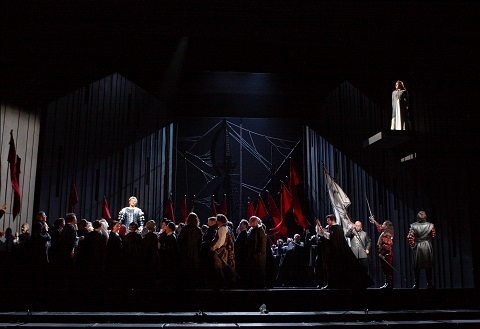

Titus Lightens Up in Saint Louis

It made me laugh (and in a “good way”).

Productions of this least performed of Mozart’s mature operas usually are stiffly formal, with somber recitatives serving mostly as a respite from one extended aria after another, often posing as more a costumed concert than a viable dramma per musica.

Director Stephen Lawless and a witty translation by Daniel Dooner may have changed all that forever. Political intrigue still looms large in the telling of the story (how could it not?), but the plot twists hinge on a sex-kittenish Vitellia leading Sesto around by his . . .da capo aria. Have you ever laughed out loud as this villainess vamps the conflicted patrician? Has anyone? We did!

René Barbera

René Barbera

This does not mean to suggest that Mr. Lawless has encouraged gratuitous schtick. No, rather he has rooted the character relationships in truthful interaction, underscoring the naughty, lethal game being played out by a vengeful, power hungry daughter of the deposed emperor. He also understands that there is much about the piece that is uncompromisingly dramatic, infused with profound human emotions. He trusts that those moments will take care of themselves and be even better for some light-footed balance. His effective use of the playing space included having the chorus positioned in the house aisles for the more formal court scenes.

The director has been gifted with a cast that is nigh unto perfection. As Vitellia, Laura Wild seems well on her way to becoming the Mozart soprano of choice. Her creamy, evenly produced tone had outstanding presence in every register and she colored it beautifully to reflect her changing moods, starting out teasing and urging, and ending up repentant and confessorial. Ms. Wild is also highly adept at executing the florid writing and ornamentations, suggesting a woodwind-like quality that illuminated every extended melisma. Her dramatic gifts equal her splendid instrument, most especially her deft, subtle comic timing.

The title role can often be eclipsed by the musical machinations swirling around him, but not so here. René Barbera returned to OTSL, having scored early career successes here in comic roles in The Daughter of the Regiment and The Elixir of Love. Happily, Mr. Barbera found just as congenial a fit with the clement, benevolent emperor, his gleaming tenor ringing out with alluring, stylish aplomb. His is one of the most easily produced, engagingly warm male voices currently before the public, and his ingratiating charisma makes his every performance a joy.

Monica Dewey and Emily D’Angelo

Monica Dewey and Emily D’Angelo

Whereas many practitioners of this role limit themselves to projecting the high-handed nobility of the emperor, René also incorporates all of the conflicted humanity, the deep hurt of his betrayal, and a convincing personal debate of whether or not to execute his beloved friend. You simply won’t see a more persuasive, well-rounded performance of the titular hero than that by René Barbera.

The two trouser roles were uncommonly well cast. Sesto has much of the opera’s very best material, and Cecelia Hall was more than up to the task. Her pliant, plangent mezzo created a convincing case for a lovesick, gullible youth, blind to the fast that he is being manipulated not only to betray his best friend, but also to commit a heinous crime. Ms. Hall made Parto, parto into a finely detailed musical journey as she mused and debated her inevitable course of action.

Emily d’Angelo was a potent match with her assured traversal of Annio. Her vibrant, focused tone was flexible and expressive, but also had a nice hint of metal in it that convinced us Annio was a headstrong foil for Sesto. Ms. D’Angelo’s demonstrative reading of her dramatically florid aria won one of the show’s biggest ovations. Icing on the cake: Both ladies-as-boys were lanky and trim, and were utterly convincing as two juvenile men.

(L to R) Laura Wilde, René Barbera, Monica Dewey, and Emily D’Angelo

(L to R) Laura Wilde, René Barbera, Monica Dewey, and Emily D’Angelo

Rounding out the soloists, Monica Dewey was a jewel of a Servilia. Ms. Dewey doesn’t have as much stage time, but her gleaming, poised soprano and delightful stage manner immeasurably enhanced every scene she was in. As Publio, Matthew Stump’s solid bass-baritone and imposing stature provided a welcome balance.

Leslie Travers has provided a handsome set design that suggests ancient Rome, counter-balanced with a luxurious costume design that is more rooted in the time of the opera's composition. The rather severe formal attire for the chorus and most principals was rather severe, with black and white waistcoats, capes and tri-corn hats for the men (of both sexes) and chorus, and formal gowns for Servilia. Titus and Vitellia were afforded luxurious, red raiment, although Titus' costumes straddled both color palettes.

The environment includes a huge rectangular platform, subtly painted with a Roman street map, presided over by an immense suspended eagle sculpture suggestive of the Roman SPQR standard, with olive branch and arrows in its respective talons. This eagle de-constructs remarkably as the city is consumed by fire, and crumbles to the floor in four separate pieces as black “ash” confetti falls from the flies. Adding to the dramatic effect was Christopher Akerlind’s masterful lighting design.

Last but most certainly not least, this performance of Titus marked Stephen Lord’s last appearance on the podium as longtime Music Director. Maestro Lord has given us a lot to be grateful for over his tenure, but none more so that this lovingly rendered, stylistically correct, and dramatically propulsive reading of a Mozartean gem. His rapport with the singers and instrumentalists alike was remarkable and his inspired leadership was of the highest order. Bravo, Maestro, e buona fortuna!

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Vitellia: Laura Wild; Sesto: Cecelia Hall; Annio: Emily d’Angelo; Publio: Matthew Stump; Tito: René Barbera; Servilia: Monica Dewey; Conductor: Stephen Lord; Director: Stephen Lawless; Set and Costume Design: Leslie Travers; Lighting Design: Christopher Akerlind; Wig and Make-up Design: Tom Watson; Choreographer: Seán Curran; Chorus Master: Cary John Franklin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/TITUS_0288a.png

image_description=(L to R) Cecelia Hall and Laura Wilde [Photo by Ken Howard]

product=yes

product_title=Titus Lightens Up in Saint Louis

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: (L to R) Cecelia Hall and Laura Wilde [Photos by Ken Howard]

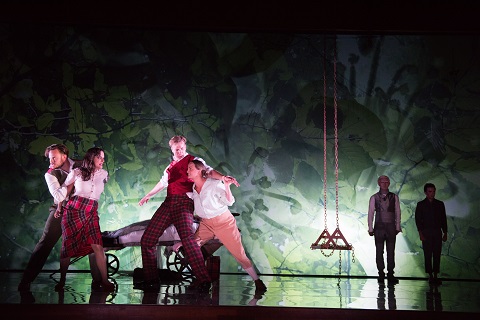

Il turco in Italia: Garsington Opera

The production is set in a Naples of the 1950s. But this is a witty picture-postcard Naples, with clean-cut healthy gypsies, and sunny temperaments all round; Francis O'Connor's giant postcard forming a backdrop from which Fiorilla (Sarah Tynan) and Geronio's (Geoffrey Dolton) house appears, and the prow of Selim's (Quirijn de Lang) yacht dramatically pierces through. Prosdocimo's (Mark Stone) balcony overlooking the bay is always in view, and we see Prosdocimo at work constantly throughout the opera.

Duncan's production was very much a combination of music and movement, not for nothing was Nick Winston movement director and assistant director. Each solo and ensemble was carefully and wittily choreographed, in a way which charmed and delighted yet emphasised the artificiality of Rossini's drama. Yet Duncan and Winston never pulled focus, and the show was a brilliantly entertaining piece of musical theatre which ensured that we always concentrated on the right people on stage. The large set pieces mirroring Rossini's big ensembles were a particular delight.

As yet the production seems slightly under-cooked, as if there has not been quite enough rehearsal time on the Garsington stage. I was aware of small ensemble problems, and the fact that complex vocal ensembles are accompanied by complex movements does make the production a particular challenge. For the first time since coming to Garsington Opera's new home, I was aware of the sheer width of the stage, perhaps because Francis O'Connor's set, with its large postcard back drop set at an angle, was rather acoustically unhelpful, projecting sound at an angle.

In many ways Il turco in Italia is one of the most human of Rossini's comedies, and the character's less cardboard cut-out than some. But Duncan's production seemed to be encouraging us to enjoy the piece as a mechanism, and it did not always bring out the humanity of the characters. Perhaps, once the production has bedded in this will happen more, but you felt that the cast were concentrating more on performing a show for us rather than interacting as characters. There were, however, strong individual performers and those returning to the production (Quirijn de Lang, Mark Stone and Geoffrey Dolton) were most successful at making us care for their characters.

Geoffrey Dolton (Geronio),Mark Stone (Prosdocimo),Luciano Botelho (Narciso). Photo credit: Alice Pennefather.

Geoffrey Dolton (Geronio),Mark Stone (Prosdocimo),Luciano Botelho (Narciso). Photo credit: Alice Pennefather.

Mark Stone, on stage for most of the time and often acting as puppet master, really made the show. His is not always a natural Rossini voice, but he brought a frankness, openness and vivid sense of character to Prosdocimo which made you care for him, and made his need to find a plot and write his play really matter.

Quirijn de Lang in the title role as Pasha Selim really looked the part, even managing to look suave, elegant and sexy in a series of embarrassing be-jewelled mini-turbans. De Lang moved with suaveness and elegance, and really encapsulated the sort of untrustworthy lounge-lizard familiar from films (though to characterise a Turk like this seemed, perhaps, borderline racist). But this is a Rossini buffo bass part (the original singer also created Mustafa in L'Italiana in Algeri), and whilst I can understand the wish to try to re-invent the character somewhat, I would have liked a little more vocal swagger from De Lang. He sang Rossini's vocal lines efficiently though his passagework was a trifle smudgy, I would have liked more vocal bravura.

Geoffrey Dolton (Geronio), Quirijn de Lang (Selim). Photo credit: Alice Pennefather.

Geoffrey Dolton (Geronio), Quirijn de Lang (Selim). Photo credit: Alice Pennefather.

Sarah Tynan brought real vocal fireworks to the role of Fiorilla and her account of Fiorilla's final aria, when she thinks she is being divorced by Geronio, managed to combine bravura singing with the right degree of pathos. Selfish and uncaring of the men around her, Fiorilla is not the most sympathetic of characters, and for most of the opera we could admire the beauty of Tynan's singing and the incredibly stylish figure she cut on stage without really caring for Fiorilla. But perhaps this is churlish given the complexity and elegance of Tynan's singing.

Sarah Tynan (Fiorilla). Photo credit: Alice Pennefather.

Sarah Tynan (Fiorilla). Photo credit: Alice Pennefather.

Katie Bray, as Selim's former lover Zaide, had perhaps an easier job to make her character sympathetic as the wronged innocent, but Bray really made Zaide count. She combined a vivacity with warmth of tone, and created a real sense of character. Geoffrey Dolton had the gift of being able to be terrifically funny, whilst still making us care for poor put-upon Geronio, constantly being imposed upon by his wife. Luciano Botelho bravely essayed the challenging role of Narciso with its high-wire acrobatics (it was written for Giovanni David who created Rodrigo in Otello and whose range went, easily, up to high F). Botelho has an attractive lyric tenor voice with a delightful stage presence, but when singing in alt his voice had a tight, edgy quality. Some of this may indeed be first night nerves, but you felt that a more acoustically helpful set might have added a little warmth. Jack Swanson made a very personable Albazar and you wished that he had more to do.

In the pit, David Parry drew some not unstylish playing from the orchestra, though we were also aware of the challenge of keeping some of the ensembles on track.

This was an enjoyable evening in the theatre, with some brilliant theatrical moments and engaging singing. Most of the audience will have gone home happily entertained, but I felt that the production had the capability of being something much more.

Robert Hugill

Rossini Il turco in Italia

Selim: Quirijn de Lang, Fiorilla: Sarah Tynan, Prosdocimo: Mark Stone, Zaida: Katie Bray, Don Geronio: Geoffrey Dolton; director: Martin Duncan, conductor: David Parry, designer: Francis O’Connor.

Garsington Opera, 26 June 2017

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Garsington%201.jpg image_description=Il turco in Italia, Garsington Opera 2017 product=yes product_title=Il turco in Italia, Garsington Opera 2017 product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id= Katie Bray (Zaida) with members of the chorusPhoto credit: Alice Pennefather

Glyndebourne's wartime Ariadne auf Naxos

When, in the Prologue, the Dancing Master jokes that the commedia dell’arte troupe’s vaudeville would be better performed after the new opera that His Lordship has commissioned - because once ‘the great and the good’ have stuffed themselves at dinner they will be bored stiff by the opera, nod off, and be ready for some more zippy entertainment - Glyndebourne patrons might feel that the self-referential nudges are getting a bit sharp.

I’m not sure how many meta-layers one has to plunge through before we’re into surreal territory, but there is certainly plenty of scope for farce during Thoma’s Prologue. The Composer, an over-sensitive idealist, becomes desperate and distraught when he learns that his patron - originally a nouveau riche in eighteenth-century Vienna - has decreed that his maiden opera, a lofty rendition of the myth of the god Bacchus rescuing Ariadne from Naxos, must, owing to time pressures over the dining arrangements, be performed simultaneously with a low-brow comic romp.

During the orchestral prelude, the Music Master and a few lackeys fuss about with malfunctioning front curtains. As the fraught preparations unfold, servants mount step-ladders to pin up patriotic bunting choreographed to the gloriously sensual peaks of Strauss’s score, while grumpy army personnel and petulant singers whizz back and forth slamming doors behind them. The palm tree on the ‘set’ of Naxos wilts, emasculated by drought or by the thought of the entertainment ahead, who knows. A barbershop quartet in natty green-and-white striped blazers put their feet through their paces and try out their poses (Strauss’s score indicates that they enter in ‘goose-step’ which despite the period setting Thoma wisely eschews), while the Prima Donna dons a leopard skin coat and, towering over the haughty Major-Domo, threatens to flounce out in pique.

The only one with a cool head is Thomas Allen’s Music Master and even he is momentarily wrong-footed by the butler’s announcement of His Lordship’s unusual request. As unswervingly dependable as ever, Allen’s diction and acting is superlative in the secco recitative: he placates the chest-puffing Tenor, destined for the role of Bacchus, and cajoles the diva soprano - she’ll be deemed even more sublime when judged against such riff-raff - and all prepare to get the show underway.

As the troupe’s leading lady, Zerbinetta, tries to win round the despairing Composer with a kiss, Strauss and Hofmannsthal entwine the opera’s two themes: the role of art in society and the nature of true love. Is this kiss, as Zerbinetta suggests, just a fleeting instant never to be relived or, as The Composer hopes, an eternal moment never to be forgotten?

Four comedians (Daniel Mirosław, Björn Bürger, Manuel Günther, François Piolino), Dancing Master (Michael Laurenz) and Zerbinetta (Erin Morley). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Four comedians (Daniel Mirosław, Björn Bürger, Manuel Günther, François Piolino), Dancing Master (Michael Laurenz) and Zerbinetta (Erin Morley). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Attention is diverted, however, by looming shadows which are cast by the wings of a Luftwaffe squadron that swoops low over the gardens. The House takes a direct hit, the blast of explosive sparks usurping the promised firework display. Dinner guests, downstairs staff and artistes evacuate the burning building, with just the Composer left behind, writhing in despair, clutching his score and begging to be allowed to die with his integrity and artistic ideals intact: ‘Tod und Verklärung’ indeed.

At this point, Strauss asks us to sit back, watch the ‘hybrid entertainment’ and judge for ourselves between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, and between unwavering faithfulness and cheerful promiscuity. Thoma, however, does not present us with the opera-within-an-opera but side-steps into a different narrative. The director professes to wish us to imagine that ‘something major happens between Parts 1 and 2’ and that the catastrophe of war has thrown The Composer ‘into a more urgent situation’.

So, we return to the manor house a few months later and discover that it is now serving as a hospital for the wounded and traumatised. Instead of naiads we have Florence Nightingales who tend to the nightmare-afflicted PTSD sufferers. To account for the presence of Zerbinetta and the harlequinade, Thoma turns them into ENSA entertainers who are preparing a wartime variety show to perk up the patients.

I’m not sure that soft shoe shuffles and musical hall ditties are the best kind of music therapy for the severely traumatised. When the sleeping Ariadne wakes, she entreats her entertainers to be relieved of the heartbreak of life; for a moment, I was reminded that the popular translation of the acronym ENSA was ‘Every Night Something Awful’.

In fact, the dapper quartet - Björn Bürger (Harlequin), François Piolino (Scaramuccio), Daniel Mirosław (Truffaldino) and Manuel Günther (Brighella) - croon charmingly and gambol with panache. And, taken on its own terms Thoma’s concept works well. The problem is that it has nothing to do with Strauss and Hofmannsthal’s intention that after the ‘realism’ of the Prologue we should be offered an artifice, the juxtaposition cleverly guiding us to interrogate the relationship between art and life. In literalising the question - making the Composer ‘face the reality that not only artistic interferences but the outside world are breaking into his ivory tower’ - Thoma disturbs the subtle balance and interplay devised by the original creators.

That said, this cast are so good that one can push such matters aside and simply enjoy the fantastic singing. Angela Brower’s Composer has theatrical presence and flashes with fury when his dream debut is being sabotaged. Brower is convincingly elevated and ecstatic when singing of the redeeming power of music, shaping the arioso beautifully.

Erin Morley’s frivolous, flirtatious Zerbinetta injects some vitality amid the misery and morbidity. When teasing The Composer, Morley apes his lyricism with tenderness, and her soprano sparkles through the roulades of her virtuoso showpiece, in which she advises Ariadne to adopt a laissez faire worldliness in her romantic liaisons. Her agility and reliability at the top did not seem to merit the punishment - being locked into a straitjacket - that the staid ward sisters inflict upon Zerbinetta.

Lise Davidsen (Ariadne). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Lise Davidsen (Ariadne). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

To say that Lise Davidsen is head-and-shoulders above the rest is not just a reflection on her statuesque height. Davidsen’s gloriously full and shining soprano transforms Ariadne - draped in a black hospital dressing-gown - back into a ‘goddess’. It’s no effort for Davidsen to swell through Strauss’s elated vocal peaks, her soprano bursting with lustre, but she can hold her huge voice back, too, shaping cool threads of sound to convey Ariadne’s vulnerability. Her reminiscence of love with Theseus was one of those moments when time seemed to stand still, triggering thoughts that at the premiere of the lament’s progenitor, Monteverdi’s 1607 setting of the same myth, it was recorded that ‘There was not one lady who failed to shed a tear’. And, in her joyful anticipation of death, Davidsen retained a grace and nobility which rose above the context.

Thoma struggles to make Bacchus’s arrival and subsequent wooing of Ariadne convincing. Bacchus has escaped from the sea nymph Circe and when he is spied approaching Naxos, Ariadne mistakes him first for Theseus and then for Hermes the Messenger of Death for whom she has been calling. AJ Glueckert’s Bacchus is not water-borne - the hospital is clearly not located by the seaside - but arrives by air. He’s a Battle of Britain pilot and it’s not clear who or what he’s escaped from, but once he has clambered through the window he’s quickly urged by the dulcet trio of Naiad (Hyesang Park), Dryad (Avery Amereau) and Echo (Ruzan Mantashyan) to continue his song and assuage Ariadne’s grief.

AJ Glueckert (Bacchus). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

AJ Glueckert (Bacchus). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

When Hofmannsthal wrote to Strauss clarifying the ‘meaning’ of the end of the opera, the composer encouraged him to publish what has become known as the ‘Ariadne letter’: the librettist explains that Ariadne and Bacchus are ‘transformed through mutual influence - she was prepared to die but reborn as immortal heavenly body; Bacchus realises the full nature of his divinity’. In the hospital ward, such thoughts seemed a long way off. Believing that she is about to be conducted to the land of the dead, Davidsen blindfolds herself and kneels before Hermes/Bacchus, but he seems unconcerned during her appeal to be released her from earthly suffering, preferring to read the newspaper. Fortunately, Glueckert’s appealing tenor is youthful and rich, and he has the stamina required to survive Strauss’s seemingly endless denial of the need for a perfect cadence. The final, lengthy duet certainly was ‘godly’.

Conducted by a sprightly Cornelius Meister, the London Philharmonic Orchestra played with airiness and clarity, the chamber-like forces rising to the challenges of Strauss’s instrumental sonorities. The lead clarinet and horn were especially elegant.

In a programme article, Thoma describes the opera as both a debate about merit of high and low art and ‘a journey from despair and disappointment to hope’. Her white hospital robe effectively becoming her wedding gown, Ariadne retreats behind the bed-curtains - which have been miraculously hoisted to the ceiling and are being gently stirred by wafts of air (has Bacchus left the window open?) - where she and Bacchus can be heard in rapturous celebration of their love.

The Composer reappears bearing a suitcase - he’s been discharged having apparently recovered from his mental anguish - and is amazed to espy his former idol canoodling with a fighter-pilot cum Greek god. In his astonishment, he spots the score of his opera lying on the table and flicks through to the final pages. There is a pause, a wry smile, a quick glance back at the transfigured couple, before our ‘hero’ departs reconciled, redeemed, restored. It is as if, in the opera’s final moments, Thoma has remembered The Composer’s climactic phrase from the Prologue: ‘Musik ist eine heilige Kunst’.

Claire Seymour

Richard Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos

Ariadne - Lise Davidsen, Composer - Angela Brower, Zerbinetta - Erin Morley, Bacchus - AJ Glueckert, Music Master - Thomas Allen, Dancing Master - Michael Laurenz, Scaramuccio - François Piolino, Harlequin - Björn Bürger, Brighella - Manuel Günther, Truffaldino - Daniel Mirosław, Naiad - Hyesang Park, Dryad -Avery Amereau, Echo - Ruzan Mantashyan, Major-Domo - Nicholas Folwell, Lackey - Edmund Danon, Officer - John Findon; Director - Katharina Thoma, Conductor - Cornelius Meister, Set Designer - Julia Müer, Costume Designer - Irina Bartels, Lighting Designer - Olaf Winter, London Philharmonic Orchestra.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/The%20Composer.jpg image_description=Ariadne auf Naxos, Glyndebourne product=yes product_title= Ariadne auf Naxos , Glyndebourne product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Angela Brower (The Composer)Photo credit: Robert Workman

June 25, 2017

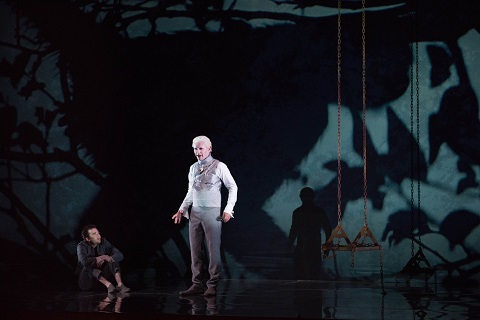

On Trial in Saint Louis

This lean, mean, darkly humorous lyric piece is based on Franz Kafka’s story as adapted by librettist Christopher Hampton and composed by the prolific minimalist Philip Glass. Its disturbing relevance proves at once contemporary and cautionary.

Josef K., you see, is being arrested for an unspecified crime. He is under constant observation, his every move is questioned; his every statement parried or parsed. Innuendo and supposition substitute for evidence. Swirling around him is an ever-morphing ensemble of quirky, murky grotesques.

The anchor of the production is the physically slight, vocally towering performance of Theo Hoffman as Josef K. Seldom off stage, Mr. Hoffman deployed his ringing baritone to tremendous effect, mining every nuance out of a wide-ranging, emotionally draining characterization. His beautifully internalized acting made K a wholly engaging personality, a sympathetic patsy whose victimization was first cruelly comical, then horrifyingly tragic. His beautifully modulated singing was even throughout all registers, and was as notable for its powerful bursts of indignation as for its introspective, whimpering cries of disbelief. Theo has created as thrillingly definitive a rendition of this central character as is likely possible.

Theo Hoffman, Susannah Biller, Keith Phares, and Joshua Blue

Theo Hoffman, Susannah Biller, Keith Phares, and Joshua Blue

And OTSL, being such a reliably renowned company, has surrounded their riveting star with an equally accomplished cast of supporting players, all of whom assume multiple roles with equal success.

Joshua Blue and Robert Mellon set the bar very high with their initial appearances as the arresting officers (Guards) with secure vocalizing, theatrical energy, and uninhibited comic business. Both had notable success in their “name” roles as Block (Mr. Blue) and the Priest (Mr. Mellon), the latter having a penultimate scene with K that drew powerful, unrestrained vocalizing from Mr. Mellon.

Matthew Lau’s weighty bass brought a smarmy gravitas to the Inspector, and a sinuous presence to Uncle Albert. Sofia Selowsky was such a free-wheeling, sexed-up Washerwoman, her stage antics almost upstaged her beautifully free, rich-toned mezzo. She also shone in her doubling as Frau Brubach and Woman. Soprano Susannah Biller offered silvery singing and detailed acting in the dual roles of . Fräulein Bürstner and Leni. The latter especially highlighted Ms. Biller’s gifts, allowing not only for awesome vocal flights but also gripping acting.

Keith Phares seemed to be having a field day with the triple challenges of the Magistrate, Assistant, and the bed-ridden (or is he?) Lawyer Huld. Mr. Phares’ fluid baritone is warm and ingratiating, and it has adopted a pleasing patina over the years. Brenton Ryan was a solid Berthold, and a willing Flogger (don’t ask), but his bright tenor and unrestrained acting chops really packed a wallop as the eccentric painter Titorelli.

The cast of The Trial

The cast of The Trial

The Expressionistic set and costume designs by Simon Banham were notable for their smart starkness and highly effective in their blunt simplicity. A square platform was placed like a baseball diamond right up to the edge of the pit. It was backed by a floor-to-ceiling wall, both constructed with rustic, light gray wooden planking. The wall has a high window, a couple of doorframes, and double barn doors dead center that open and close to reveal changeable insets.

Late in the show, the wall parts and tracks off stage, leaving only the island of the platform, almost “floating” against the all-black background. Costumes were mostly black and white, and clearly communicated each character. The brilliant lighting design was one of Christopher Akerlind’s best, with its intentionally limited use of color, and its incorporation of cock-eyed, disorienting trapezoidal projections. The simple combination of carefully selected furniture and its seamless incorporation into the staging were admirable.

Director Michael McCarthy has brilliantly harnessed all this talent into a tightly focused, beautifully controlled whole. He has seized on the Big Brother concept. When actors are not directly involved in a scene, they are observing, hovering, menacing in an intriguing variety of stage pictures. Mr. McCarthy has created an awesome ensemble with these singers, able to turn on a dime, serving as a solo character one minute, observer another, and set changer yet another, before plunging back into the action as a totally different character. This high level of ensemble playing simply does not happen without a skilled director of the caliber of Michael McCarthy.

And speaking of a “high caliber of ensemble playing” (and I was), Conductor Carolyn Kuan worked equal magic in the pit. Maestra Kuan elicited the all-important, pulsating, rhythmically precise orchestral execution, to be sure. She also drew an abundance of color from her players and singers alike, achieving a varied palette of satisfying musical effects. In a score that has a fair share of twitchy, angular components, Ms. Kuan managed to cue each and every entrance with an incredible accuracy.

The Trial may not send you out of the theatre humming a tune, but owing to this illuminating production, it cannot help but leave you challenged and changed.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Josef K.: Theo Hoffman; Franz (Guard 1)/Block: Joshua Blue; Willem (Guard 2)/Court Usher/Clerk of Court/Priest: Robert Mellon; The Inspector/Uncle Albert: Matthew Lau; Frau Grubach/Washerwoman/Woman: Sofia Selowsky; Fräulein Bürstner/Leni: Susannah Biller; Magistrate/Assistant/Lawyer Huld: Keith Phares; Berthold, a Student/Flogger/Titorelli: Brenton Ryan; Conductor: Carolyn Kuan; Director: Michael McCarthy; Set and Costume Design: Simon Banham; Lighting Design: Christopher Akerlind; Wig and Make-up Design: Tom Watson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/TRIAL_0591a.png

image_description=Robert Mellon, Theo Hoffman, Joshua Blue, Susannah Biller, and Keith Phares [Photo by Ken Howard]

product=yes

product_title=On Trial in Saint Louis

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Robert Mellon, Theo Hoffman, Joshua Blue, Susannah Biller, and Keith Phares [Photos by Ken Howard]

A Traditional Rigoletto in Las Vegas

On June 9, 2017, Opera Las Vegas presented a traditional production of Verdi’s Rigoletto conducted by Music Director Gregory Buchalter with a cast headed by veteran baritone Michael Chioldi. Before the curtain rose, however, Artistic Director James Sohre presented a beautiful glass plaque to retiring General Director Luana DeVol. One of the world’s most successful dramatic sopranos and an able fundraiser, it will be extremely difficult to find a replacement for DeVol.

The Judy Bayley Theatre is a five-hundred-fifty-seat venue at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas. The stage is reasonably wide but it isn’t very deep, so singers could easily be heard from upstage. Designer Lily Bartenstein’s set consisted of shoulder-high platforms with stairs on one side and frames that turned open spaces into windows. Minimal but functional, they allowed Director Cynthia Stokes to tell her story. The Duke had his court, Gilda and her father an apartment, Sparafucile a workspace and Maddalena, as she herself sings, had no roof over her bed.

Kirk Dougherty as the Duke and Danielle Marcela Bond as Maddalena

Kirk Dougherty as the Duke and Danielle Marcela Bond as Maddalena

Chioldi, a most convincing Rigoletto, was a man in psychological pain from the begining of the opera. His fear and his vulnerability to the whims of the nobility were evident in every meaty, well-colored phrase he sang. His sweet innocent daughter was his only joy, so when she was harmed he had nothing left. In his second act aria, “Cortigiana, vil razza dannata,” he lashed out at the courtiers with fiery tones that could have brought on his arrest, but he finished by revealing his heartbreak over the abduction of his daughter.

Kirk Dougherty was a robust Duke, both vocally and physically. A young, rich, athletic member of the nobility, no law could come between this character and pleasure. Onlookers could understand how he managed to fascinate Gilda. His Duke sang with brilliant, energetic tones that helped make the rendition of the famous quartet a delight. Having paced his performance well, he still had plenty of voice left for the final round of “La donna è mobile” that told Rigoletto the Duke was still alive.

So Young Park has all the technical skills Gilda demands and in this performance she combined them with the utmost in artistry. She sang her “Caro nome” with total clarity, liquid phrasing and a long trill that crowned the scene with tonal beauty. Park has a complete arsenal of coloratura skills that is hard to match.

A proud noble who had been condemned to death for having confronted Mantua’s most powerful duke, Eugene Richards was a commanding Count Monterone with a well-burnished bass-baritone voice. Bass Rubin Casas was a mean and evil Sparafucile who had no compunction about killing a nobleman. He simply said his fee was higher for a duke. He sang with rich dark sounds that helped evoke interest in his character.

Emily Stephenson and Michael Parham as the Count and Countess Ceprano, along with Marco Varela as Borsa and Travis Lewis as Marullo, filled out the Mantuan Court's vocal riches. Stephanie Sadownik was a mendacious Giovanna and Danielle Marcelle Bond gave a fine rendition of Maddalena’s low-lying phrases.

Conductor Gregory Buchalter had a small group of instrumentalists to work with, but he drew a fine blend of Verdian sound from them. Together, they captured the work’s melodic greatness and its essential dramatic points, from its intense beginning and the forward motion of its many bright scenes to its culmination in darkness and death.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Conductor, Gregory Buchalter; Director, Cynthia Stokes; Duke of Mantua, Kirk Dougherty; Borsa, Marco Varela; Countess Ceprano, Emily Stephenson; Count Ceprano; Michael Parham; Marullo, Travis Lewis; Rigoletto, Michael Chioldi; Monterone, Eugene Richards; Sparafucile, Rubin Casas; Maddalena, his sister, Danielle Marcelle Bond; Gilda, So Young Park; Giovanna, her nurse, Stephanie Sadownik; Chorus Master Joseph Svendson; Set Design, Lily Bartenstein; Lighting, Ginny Adams; Costumes, Stephen dell’ Avesano @ Tri-Cities Opera.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rigoletto_Vegas_01.png

image_description=Michael Chioldi as Rigoletto [Photo by Richard Brusky]

product=yes

product_title=A Traditional Rigoletto in Las Vegas

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Michael Chioldi as Rigoletto [Photos by Richard Brusky]

Thumbprint, An Amazing Woman Leaves an Indelible Mark

The opera, Thumbprint, originated with a play called Seven, a documentary work first performed in 2008 at New York City’s Ninety-Second Street “Y.” Seven tells the stories of seven women around the world who fought for the rights and wellbeing of women and girls. Susan Yankovich told of Mukhtar Mai, a Pakistani survivor of gang rape, who became a campaigner for women's education and won a 2006 Global Leadership Award.

Beth Morrison of Beth Morrison Projects suggested that Yankovich make her section of the play into an opera libretto for Indian-American composer Kamala Sankaram. Beth Morrison Projects commissioned Thumbprint as a song cycle that was first heard in 2009. As an opera, it received its world premiere in New York in 2014 and its West Coast premiere on Thursday, June 15, 2017. This reporter saw the first Los Angeles performance of Thumbprint as part of Los Angeles Opera’s “Off Grand” series performed at the REDCAT Theater.

Phyllis Pancella (Mother), Kamala Sankaram (Mukhtar Mai) and Leela Subramaniam (Annu)

Phyllis Pancella (Mother), Kamala Sankaram (Mukhtar Mai) and Leela Subramaniam (Annu)

Indian-American composer Kamala Sankaram wrote a strong score for this opera. Her music is powered by short rhythmic phrases that drive it forward and undergird it with dramatic force. A singer herself, Sankaram wrote fine ensembles as well as arias and her music utilized the most colorful parts of each artist’s range. With soprano Leela Subramaniam as Annu singing above her and mezzo-soprano Phyllis Pancella as the Mother singing below her, Sankaram’s Mukhtar begins her story as a charming young girl in a loving family. When Mukhtar’s twelve-year-old brother was accused of a sexual offense, she volunteered to apologize for him. Her apology was not accepted and she was physically assaulted. Sankaram’s music, which had been delightfully decorated by the flute, then lost its light hearted charm to become stark and dramatic.

Sankaram's exquisitely colorful score gave Music Director Samuel McCoy six players to accompany the singers: percussionist Brian Shankar Adler, bass player Greg Chudzik, pianist and harmonium player Mila Henry, flutist Margaret Lancaster, violinist Andie Springer, and violist Philippa Thompson. Although they were few in number, they presented Sankaram’s fascinating and repetitive fusion of Western and Indian music with ever increasing intensity.

Kamala Sankaram (front) as Mukhtar Mai, with Phyllis Pancella (Mother)

Kamala Sankaram (front) as Mukhtar Mai, with Phyllis Pancella (Mother)

Director Rachael Dickstein, Scenic Designer Susan Zeeman Rogers, and the video designers of Automatic Release showed Mukhtar’s road to social redemption both on a screen and as a route around the stage. She walked across rectangular platforms that were also used to represent home furniture, a desk in a police station and the dock of a Pakistani Court. Kate Fry’s colorful Pakistani costumes featured long pants under full skirts and headscarves with intriguing designs for the women. The men wore light weight long shirts over slim pants.

Thumbprint is a dramatic piece in which the voices convey a story rather than concentrate on aural beauty. Sankaram, Subramaniam, and Pancella colored their tones so that they told of the events in Mukhtar's life with sound as well as words. Tenor Steve Gokool’s bright, powerful voice was the perfect foil for actor Manu Naroyan’s evil characters, while Kannan Vasudevan’s aptly created smaller characterizations filled out the roster of villagers. Although there were no supertitles and some words were hard to understand, Dickstein made sure that no member of the audience missed Mukhtar’s message.

At the end of the performance there was a Talk-Back at which the opera’s heroine, Mukhtar Mai, was present. Through a translator, she told us that her attackers were free on appeal and would probably never serve time in prison. She has put together a foundation, however, that provides education and support for women in Pakistan. She noted that little by little the tide is turning as village women begin to realize they have the power within themselves to ameliorate their situation.

Maria Nockin

Cast and production information:

Composer, Kamala Sankaram; Librettist, Susan Yankowitz; Creative Producer, Beth Morrison; Director, Rachel Dickstein; Music Director, Samuel McCoy; Lighting Design, Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew; Scenic and Object Design, Susan Zeeman Rogers; Costume Design, Kate Fry; Mukhtar, Kamala Sankaram; Mother, Minister of Justice, and other roles, Phyllis Pancella; Father, Judge, and other roles, Steve Gokool; Faiz, Police Chief, and other roles, Manu Narayan; Abdul, Shakur, Imam, other roles, Kannan Vasudevan; Annu and other roles; Leela Subramaniam.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/thumbprint-0613-01.png

image_description=Kamala Sankaram as Mukhtar Mai [Photo by Larry Ho]

product=yes

product_title=Thumbprint, An Amazing Woman Leaves an Indelible Mark

product_by=A review by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Kamala Sankaram as Mukhtar Mai [Photos by Larry Ho]

June 23, 2017

Kaufmann's first Otello: Royal Opera House, London

Iago’s gesture of vehement vexation opens the drama with the shattering of a symbol of deception and artifice that complements Iago’s masking of his ‘self’ - ‘I am not what I am’. Then, at the close of Act 2, Otello is confronted by a mirror which reflects back at him a masked figure. Finally, prone and emasculated, following a seizure brought on by Iago’s ‘proof’ of his wife’s unfaithfulness, the Moor is himself wreathed with this mask by his puppet-master. But, the destruction of this theatrical adornment at the start of the opera reminds us, too, that Iago’s iniquity will be exposed, as Shakespeare’s Iago himself foresees: ‘when my outward action doth demonstrate/ The native act and figure of my heart … I will wear my heart upon my sleeve/ For daws to peck at’.

Moreover, in placing Iago, rather than the eponymous Moor, centre-stage in the initial moments, Warner foregrounds an equality of dramatic status which mirrors Shakespeare’s text. Iago speaks by far the greater number of lines and it is his compelling soliloquies which make the audience almost complicit in the villain’s stratagems. And, in a letter to Boito, Verdi described Iago as ‘the Demon who moves everything’, noting that ‘Otello is the one who acts: he loves, is jealous, kills and kills himself.’ Despite Otello’s titular status, in Warner’s production Jonas Kaufmann’s introspective Moor and Marco Vratogna’s vengeful ensign are equal participants in the tragic unfolding, in a production which embraces the protagonists within a strong ensemble.

Jonas Kaufmann (Otello). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jonas Kaufmann (Otello). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

That said, it was undoubtedly Kaufmann whom the multi-national audience had come to see. And, tackling the role for the first time, he did not disappoint. Otello’s fairly low tessitura suits Kaufmann’s tenor which has baritonal resonances and he was pretty fearless in approach, holding nothing back vocally at the challenging peaks. Otello’s fears were passionately exclaimed in ‘Ora e per sempre addio sante memorie’; in contrast, ‘Dio mi potevi scagliar’ was distressingly meditative - often the barest whisper conveyed wistful introspection - though perhaps lacking a full palette of colour. Kaufmann’s Act 1 duet, ‘Già nella notte densa s'estingue ogni clamor’, with Maria Agresta’s Desdemona was particularly beautiful, though in general I wasn’t entirely convinced by the chemistry between the doomed lovers; here, as they narrated the tale of their courtship, their desires seemed aroused as much by their own vocal mellifluousness as by their memories of romance and adventure.

Kaufmann’s Otello is no commanding hero, though. His ‘Esultate!’ is not a thunderous entrance that would silence a storm; rather, this Otello surfaces within the crowd, though the victor’s cry rings with bright strength. Moreover, if he does not convey imposing ascendancy then neither is Kaufmann’s Otello petulant, despite the fact that Boito has his ‘hero’ repeatedly burst into rage. Indeed, the brevity and orchestral power of our introduction to Otello suggests that, in Verdi’s eyes at least, he is a figure of more than simply military might and physical power.

Boito and Verdi have created not a ‘noble savage’ - whom Shakespeare’s contemporaries might have considered overcome by his innate bestial sensuality (and Kaufmann is not blacked up, which is unproblematic given that Boito does not draw much attention to the Moor’s race and colour) - but a man of solipsistic susceptibility, which Kaufmann’s quiet anguish captures perfectly. His fragile pianissimos become an apt representation of the linguistic fragmentation of the text’s ‘Othello music’, as the grandiose imagery of ‘Olympus-high’ oceans ruptures into stuttering banality - ‘ Pish! Noses, ears, and lips.’ Verdi cannot disrupt the beauty of the vocal line in the way that Shakespeare deconstructs the linguistic metre and syntax, and so, in this way, Kaufmann’s reticence becomes almost a rhetorical strategy.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

And, it is a strategy echoed in Boris Kudlička’s minimalist designs which profess Warner to be more concerned with the internal than the external workings of the drama. The walls of Kudlička’s ‘black box’ slide inwards, their trellis-tracery allowing figures to eavesdrop furtively, while also elegantly referencing Moorish filigree lanterns. We are presented with a psychological chamber in which we seem to explore what Melanie Klein termed ‘projective identification’: that is, the projection onto others of feelings that inspire suffering or thrill within a subject. If we view the opera in this way (as Richard Rusbridger does in his article in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis , February 2013), Warner’s opening gesture identifies the storm with the emotional turmoil in Iago’s mind, and not, as in Shakespeare’s play, the ensuing breakdown of natural, civil and domestic order.

Marco Vratogna (Iago). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Marco Vratogna (Iago). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Indeed, Marco Vratogna’s Iago is undoubtedly hellbent on Hades. There is nothing clandestine about his malignity, though I’d suggest that in fact a little more serpentine slipperiness would not go amiss: after all, his ‘honesty’ as perceived by those around him, must be credible. Vratogna has a strong upper register - such as can provide propelling drive in the Brindisi - but his occasional hoarseness fittingly reminds us that Iago is a rough soldier, whose coarseness may have inclined Otello to promote the more urbane Cassio to be his lieutenant. That said, Vratogna’s light-breathed insinuations floated into Othello’s ear with the elegance of a lover’s discourse.

If Iago is ‘the Devil’, rejecting God in his Credo - ‘I believe that the righteous man is a mocking actor both in his face and in his heart, that all in him is a lie, tear, kiss, glance, sacrifice and honour’ - then Desdemona is his antithesis, an angel of saintliness, whose innocence and grace Iago is driven to violently expunge. There is little of Shakespeare’s playfulness or feistiness in Boito’s characterisation. Maria Agresta, often pushed to the hinterlands of the production, until the final scenes, sings with a rhapsodic lustre and fullness of tone that perhaps betrays a sensuality less than innocent, but her Willow Song and Ave Maria are composed and restrained, an acceptance of the inevitable and a welcoming of the hereafter.

Jonas Kaufmann (Otello) and Maria Agresta (Desdemona). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jonas Kaufmann (Otello) and Maria Agresta (Desdemona). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The rest of the cast are by no means ‘secondary’. Frédéric Antoun’s Cassio is elegantly persuasive but Iago’s duet with Cassio in Act 3 highlights the latter’s narcissism and superficiality. Thomas Atkins’ Roderigo and Kai Rüütel’s Emilia are finely drawn. A sense of Venetian grandeur is offered by Sung Sim’s noble Lodovico and Simon Shibambu’s courtly Montano.

Pappano conjures blazing intensity from the ROH players. Not everything is precise, but there is a visceral quality to both the orchestral and choral climaxes which is countered by subtleties such as the string sonorities of the Prelude to Act 3.

Warner’s vision does stumble at times: the arrival of the masted ship and the extending of the high gangplank for Desdemona’s disembarking lack refinement; the shattering of the winged lion seems cliched; and, perhaps because there is a focus on the interior rather than the exterior, some of the movement blocking, excepting the Chorus, is uninventive.

But, Iago’s greatest masterstroke is respected. He can literally turn white into black: ‘So will I turn her virtue into pitch,/And out of her own goodness make the net/ That shall enmesh them all.’

And, so, in the final moments, the ‘black box’, inflamed by Bruno Poet’s illumination, is made to contain a snow-white pearl - the white-upon-white canvas of Desdemona’s doom. The sumptuous bed is, perhaps inevitably, smeared with a painter’s flourish of red blood. This serves as a visual emblem of the tragedy’s catalyst and its conclusion (but the neon ‘halo’ is superfluous, surely?). For, it is the strawberry-spotted handkerchief which is Iago’s prime tool of deception and it is this antique token of affection which subsequently serves as an agent of truth, exposing his iniquity. Thus, it is, paradoxically, a delicate symbol of overpowering destiny. As Othello despairs, ‘Who can control his fate?’

Claire Seymour

Verdi: Otello

Otello - Jonas Kaufmann, Desdemona - Maria Agresta, Iago - Marco Vratogna, Cassio - Frédéric Antoun, Roderigo - Thomas Atkins, Emilia - Kai Rüütel, Montano - Simon Shibambu, Lodovico - In Sung Sim, Herald - Thomas Barnard; Director - Keith Warner, Conductor - Antonio Pappano, Set designer - Boris Kudlička, Costume designer - Kaspar Glarner, Lighting designer - Bruno Poet, Movement director - Michael Barry, Fight director - Ran Arthur Braun, Royal Opera Chorus (Concert Master - Vasko Vassilev), Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Wednesday 21st June 2017.

Image=http://www.operatoday.com/2796ashm_0914%20JONAS%20KAUFMANN%20AS%20OTELLO%2C%20MARCO%20VRATOGNA%20AS%20IAGO%20%28C%29%20ROH.%20PHOTO%20BY%20CATHERINE%20ASHMORE.jpg image_description=Otello, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product=yes product_title=Otello, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Jonas Kaufmann and Marco VratognaPhoto credit: Catherine Ashmore

June 22, 2017

Don Carlo in Marseille

Metteur en scène Charles Roubaud is nearly synonymous with the Opéra de Marseille, having initiated his opera career there in 1986 (an acclaimed Don Quichotte, seen in San Francisco in 1989). This Don Carlo is his 20th mise en scène for Marseille.

Roubaud is a minimalist. Eschewing all metaphor he favors image. Thus in recent stagings he has made much use of video washes projected onto substantial, abstract architectural shapes. His stagings occur in abstract ambience rather than specific locale. For this Don Carlo he was joined by long term collaborators, Avignon based set designer Emmanuelle Favre and Marseille based costume designer Katia Duflot. The video designer was Virgile Koering (of Montpellier origins).

Roubaud is also a conceptualist, imagining Verdi’s auto de fé spectacle as a relatively intimate court encounter between father and son, overseen by church and state, courtiers were lined up as observers. Finally he imagined a video procession of Flemish youth marching to their martyrdom. Nothing more.

Yolanda Auyanet as Elisabetta, Teodor Llincal as Don Carlo

Yolanda Auyanet as Elisabetta, Teodor Llincal as Don Carlo

Based on intimacy and privacy such conceptual simplicity informed every scene. Don Carlo lay supine at the feet of Elisabetta for much of their fraught, post Fontainebleau encounter (this was the 4 act version). Eboli lay supine at the feet of Elisabetta to confess her betrayal. Every scene deployed its actors in abstract, emotionally charged positions, or abstract, strategically defined positioning rather than in active dramatic encounter.

Roubaud’s found Verdi’s theater not in Schiller’s drama, but in the expansion and implied collision of emotional worlds. Thus the theatrical climax fell onto the string of four huge arias that cap Verdi’s opera. Philip II’s Ella giammai, m’amò, Eboli’s “O don fatal,” Posa’s “Per me giunto è il di supreme, Elisabetta’s “Tu che le vanità conosce” riveted us to the complexity and richness of existentially separate human worlds. Roubaud made Verdi’s theater not in dramatic encounter but in the discovery and definition of these coexisting worlds.

Yolanda Auyanet as Elisabetta, Jean-François Lapointe as Rodrigo, Sonia Ganassi as Eboli, Carine Sechaye as Tebaldo

Yolanda Auyanet as Elisabetta, Jean-François Lapointe as Rodrigo, Sonia Ganassi as Eboli, Carine Sechaye as Tebaldo

This concentration was only possible with the complicity of the pit. Conductor Lawrence Foster found Verdi’s empathy with his tormented souls, and allowed it to expand and elaborate without boundary. Dramatic moments were indeed pointed, but only to extend possibility of amplitude and expansion of the existential moment.

With such an operatic poetic occurring simultaneously on the stage and in the pit the historical veracity of Verdi’s actors was far less significant than the actors abilities to live the moment. And that they did without exception. If bass Nicolas Courjal is too young to be an actual Philip II, he is vocally able to find an immediacy of plight with an energy and passion that were not resignation. His was the presence and the urgency of character that declared Philip II the central force of Verdi’s opera, not its tired victim.

Jean-François Lapointe brought unusual intelligence to Marquis de Posa with a maturity of male vitality, purity of resolve and duplicity, establishing himself as the moral equal of Philip II in beautiful, powerful voice. Italian mezzo Sonia Ganassi as Eboli unleashed sophisticated, mature vocalism and Rossinian confidence (plus solid, secure high notes) to make Eboli grovel magnificently in self pity. Spanish soprano Yolanda Auyanet’s Elisabetta had the purity of voice to project marital, maternal and filial innocence and the power of character and voice to explode in her confusion.

Physically and vocally robust, Romanian tenor Teodor Ilincai established a full voiced and straight forward confidence for history’s troubled young prince. And he was well able to appropriately soften and manipulate his tone as needed, This solid Don Carlo was the powerful catalyst for Elisabetta, Eboli, Rodrigo and Philip II to achieve the epitome of great lyric theater — a seemingly infinite state of simultaneous, suspended realities.

Immobile, directly in front of a huge white light cross bass Woytek Smilek’s Grand Inquisitor assumed terrifying terrestrial authority, A 2014 Operalia winner, soprano Anaïs Constans promised celestial peace for his victims in truly heavenly voice.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Elisabetta: Yolanda Auyanet; Eboli: Sonia Ganassi; Tebaldo: Carine Sechaye; Une Voix Céleste: Anaïs Constans; Don Carlo: Teodor Ilincai; Philippe II: Nicolas Courjal; Rodrigo: Jean-François Lapointe; Le Grand Inquisiteur: Wojtek Smilek; Un Moine: Patrick Bolleire; Comte de Lerma: Éric Vignau; Députés Flamands: Guy Bonfiglio, Lionel Ddelbruyere, Jean-Marie Delpas, Alain Herriau, Anas Seguin, Michel Vaissiere; Un Araldo: Camille Tresmontant. Orchestre et Chœur de l’Opéra de Marseille. Conductor: Lawrence Foster; Mise en scène: Charles Roubaud; Scénographie: Emmanuelle Favre; Costumes Katia Duflot; Lumières: Marc Delameziere; Vidéos: Virgile Koering. Opéra de Marseille, June 17, 2017

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DonCarlo_MRS1.png

product=yes

product_title=Don Carlo in Marseille

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Nicolas Courjal as Philip II [All photos by Christian Dresse, courtesy of the Opéra de Marseille]

June 21, 2017

Diamanda Galás: Savagery and Opulence

Now 61 years of age, the voice is as powerful, as cyclonic and ferocious as it was when I last heard her over a decade ago in Defixiones, Will and Testament. If anything, the mezzo layer of the voice is even more deeply impressive; she bevels her vocal range so masterly to the lowest mezzo F and beyond but it’s as solid as steel; you have to return to the recordings of some of the greatest Wagnerian mezzos to find comparable depth. The projection remains fabulous - though this is a voice as brilliantly and uniquely human as it is one that is filtered through microphones and some digital processing. That it never seems micro-managed, but a genuinely kaleidoscopic prism of the extremes of the human voice remains a formidable achievement (the difference being what is possible for Galás is impossible for others). Her stunning octave range remains as secure and formidably exact as before, though with that unique hard edge, like a saw against metal, that seems in part more Bel Canto than purely lyrical.

It’s only when you come to the folk song O Death (which some might know from the Coen Brothers) towards the end of the concert that the sheer vocal range and the extended techniques make an unforgettable impression. Many will never forget the thrilling sound of her floating long phrases - absolutely Straussian in their beauty - and the pyrotechnic vocal somersaults that enshrine the psychodramatic narrative that slices like a scythe through sonics crackling like a current of electricity or a semi-tuned radio. If this wrenching performance made you feel like glass is being crushed under a lethal stiletto or gravel is being fed down the throat until you howl - then it’s because that’s exactly how she sings it. There’s no question that this is still a voice that empowers women in a starkly dramatic way, though as so often is the case with this singer sentimentality is eschewed.