January 30, 2019

Diana Damrau’s Richard Strauss Residency at the Barbican: The first two concerts

As the first recital amply demonstrated, there is a linear path - in German lieder especially - that reaches its Romantic highpoint with Strauss. But as Debussy himself said it’s also impossible to resist the overwhelming power of his music and whether this is on the smallest or biggest of scales (both of which we had here) Strauss’s music can seem almost cinematographic. Debussy had in mind Ein Heldenleben when he pointed to the “book of images” that Strauss’s music resembles - and it was this very work which closed the second concert.

Diana Damrau, it should be said, is not one of those sopranos whose voice easily resonates in a hall the size of the Barbican. The lack of power, and sheer heft, the occasional unwillingness to project the voice more dramatically, can sometimes make the sound she produces seem uncommonly small. But the depth, and range, of her register is quite remarkable despite this one drawback, and it’s certainly not one that is evident all the time. The big notes might feel a little compressed, but her pianissimos are astonishing. As quiet as some of her singing can be, the clarity of what she is singing is like a perfectly cut diamond. On the other hand, the shimmering, almost silver-like tone, the ability to convey youthfulness and warmth, and the unmannered phrasing, places her in a different league to many lieder singers performing Strauss today. Those floating high notes, the perfectly sustained legato and the ability to draw you into the music is often quite magical. Here we have a singer much closer to Lisa Della Casa, Lucia Popp and Margaret Price rather than, for example, Jessye Norman - who in one of her last Wigmore Hall recitals sang Strauss with such power you could feel the waves of sound washing over you.

Damrau opened her first recital with five songs by Liszt. Liszt’s canon of lieder, and his place in the pantheon of great song composers, has never seemed as assured, even today, as those written by Schubert, Wolf or even Strauss. And yet, the line between Liszt, Wolf and Strauss - all of which appeared in this first recital - couldn’t really be clearer. Although perhaps not immediately obvious at first, this intuitive and clever programming of Damrau’s opening concert pointed towards the climax of the second. This was entirely about perspective, about the revolution in Romanticism, and the Neo-German path of lieder and orchestration which went beyond lyricism and opened up the gates towards drama and expressionism in song, and the great Tone Poems that Strauss composed at the close of the Nineteenth Century.

One of the dominant features of this recital was how much the piano mirrored so much of the text - and it began with Liszt. Helmut Deutsch was certainly much more than an accompanist in these opening Liszt songs - though perhaps the somewhat symphonic nature of some of the piano writing, allied with Damrau’s slightly more introspective singing, made him overly dominant at times. In ‘Die Loreley’, for example, the sweeping, flowing - even unrelenting - power of the Rhine was a little more turbulent and overwhelming than one sometimes hears in this song. A stronger voice might have made the piano writing seem less overloaded - but it was thrilling, even if the magic shifted from the voice to Liszt’s piano scoring. But despite this, Damrau often embraced the Homeric - in ‘Die Loreley’ the luring of sailors to their deaths conjured up allusions of the Sirens in The Odyssey: she was at once seductive and devastating in her ability to wreak torment as a temptress of fate. If the vocal strength sometimes fell a bit short, there was never a shred of doubt that Damrau was as fine a storyteller as we’re likely to hear in the concert hall today.

If there was death, these lieder embraced nature too. Schiller - never perhaps the most luminous, or most inspired, of poets - paints a landscape of innocence and boyhood in ‘Der Fischerknabe’. This opening song set the trajectory of where Damrau was going with her Liszt lieder (which was almost to become a microcosm of the two concerts themselves). Just as the voice takes you inwards, the shifts in tonal and vocal colour fuse a distinct narrative. Perhaps more suited to Damrau’s quicksilver, lighter voice the shimmering movement of the water achieved greater reflection, and more balance with Deutsch’s playing, than in the third song ‘Es war ein König in Thule’ which sometimes seemed to elude Damrau altogether. If there’s a simplicity to Goethe’s text here, the depths to which Liszt has gone are exceptionally more demanding on a singer. One never quite felt that the nobility of this piece, or the darker, and more mysterious palette, really quite suited her, or lay easily within her range. There’s something Faustian about this song - perhaps better achieved here by Deutsch’s lugubrious blend of darkness and weight - a distinct contrast to the magnificent second song, ‘Die stille Wasserrose’ where Damrau had been so successful in being so overtly feminine, youthful and - yes - unabashedly erotic. Of all the Liszt songs this was the one which probably hit the mark best of all - one where both Damrau and Deutsch achieved a level of harmonic unity that they never quite managed in the other Liszt lieder. The softness of the piano, the breath-taking beauty of the voice was spellbinding.

There is no question that Damrau made a very persuasive argument for these Liszt songs, even to the extent that one could argue that Liszt’s setting of ‘Die stille Wasserrose’ sounded finer than the same song by Schumann. One certainly felt at times that Damrau and Deutsch were not entirely in unison - though in part this has much to do with Liszt himself who explores significantly more drama in the piano - and Deutsch wasn’t shy in displaying this. I didn’t necessarily find Damrau’s German precise or exact - in fact, it often seemed to be quite the opposite. A tendency to meld phrases into one another, clip words here and there, became a touch grating at times. This was a noticeable problem in ‘Die Loreley’ where you often expected (or should have expected) a more rounded sound and it was simply missing. The penultimate lines of the fifth stanza, for example, ‘Er schaut nicht der die Felsenrisse/Er schaut nur hinauf in die Höh’ were flexed to a state where they were pretty much inaudible.

The Vier Lieder der Mignon by Hugo Wolf were largely magnificent, however. Why Damrau should have been so strong, and compelling, in these Wolf songs isn’t hard to understand. Her gift as a singer lies in her ability to convince the listener that you are very much involved in the psychological complexity behind a composer’s imaginative re-contextualising of the words. In the case of Wolf, these Goethe settings felt incredibly well articulated and almost operatic in their depth of interpretation. Put simply, Damrau just drew you in like a viper does to its prey.

If Liszt had begun to rebalance the voice and the piano in his lieder, Wolf takes it just that bit further - and with it explores the dramatic and sensual power of a composer like Wagner, notably in Tristan, but on a much smaller scale. You sometimes felt in the Liszt songs that Damrau and Deutsch were splitting apart at times; in the Wolf lieder the effect was quite the opposite. Here, if the piano moved one way with its motivic material Damrau chose to follow it. But the obverse was also true. If in the Liszt songs Deutsch had shown he was willing to go-it-alone with the piano writing, his tendency in the Wolf lieder was to mirror more closely with Damrau’s voice.

There is certainly something disturbing, almost pathological, about Wolf’s characterisation of the Mignon setting. Helmut Deutsch instinctively sees the piano part as gravitating towards menace; Damrau, if she didn’t convey enough mystery or darkness in a song like Liszt’s ‘Die Loreley’, here enshrines Mignon with a profound sense of grief and sorrow that is manifestly deeply emotional. They were gripping to hear. Sometimes you got the feeling of a profoundly unstable relationship happening on stage (in the best possible way, it should be said). In ‘Kennst du das Land’, for example, as Damrau sang out ‘Dahin! Dahin’ you felt that Deutsch was each time on the brink of overwhelming and crushing her. Damrau would have none of it and pushed back against this ruinous cruelty by soaring above the keyboard. Wolf had sought to rebalance the relationship between his two protagonists on stage - and this was achieved with mesmerising effect by Damrau and Deutsch where neither singer nor pianist dominated the other. It was all in beautiful, perfect symmetry.

The second half of Diana Damrau’s opening recital was devoted entirely to the lieder of Richard Strauss. The chronological path of Damrau’s programme of lieder - and in the case of the second concert the Vier Letze Lieder - in one sense diverts attention away from Strauss’s singularity as a composer moving in a definite musical direction. Strauss’s songs undoubtedly look back towards the Romanticism of Liszt and Wolf - but they also embrace the Expressionism that was a hallmark of his great single-act operas, Elektra and Salome, only for Strauss to, again, look back to the Nineteenth Century in some of his final works. His output can certainly seem uneven - but so is that of Liszt and Wolf - but Strauss’s great gift was to turn a miniature piece of writing into something that was hugely impressionistic and vivid. It rather confirms the view of Strauss the composer, as described by Debussy, as one who thought largely in images and pictures.

Diana Damrau. Photo credit: Peter Meisel.

Diana Damrau. Photo credit: Peter Meisel.

If there is one thing that many of Strauss’s songs have in common - and this, too, follows on from Liszt - it’s that the accompaniment can often seem orchestral. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the song which ended the recital - ‘Cäcilie’. A highpoint of this recital - perhaps the highpoint - it was simply majestic. The demands placed on both singer and pianist are huge, but here both Damrau and Deutsch had reached a state of symbiosis that was inspired. The lushness they both brought to this song was exceptional, but so was the artistry and refined technique. If you detected agility in Deutsch’s quicksilver fingers it was because he was identifying so closely with the movement of the text. Likewise, Damrau’s breath control was exceptionally precise. If she had struggled in Liszt, her Bavarian German was much more aesthetically pure in Bavarian Strauss. Some of Strauss’s phrases in ‘Cäcilie’ can seem uncommonly long, almost meandering, but perhaps none tax the singer more than the final one and to Damrau’s credit her singing of it (“wenn du es wüsstest, wenn du es/wüsstest, du lebest mit mir!) was a miracle of voice control and pristine enunciation.

‘Einerlei’ had been the shortest of introductions to this Strauss part of the recital - almost a bon-bon in its paradigm brevity - though it wasn’t until the third song, ‘Ständchen’, that the depth of Damrau’s immersion into Strauss became more apparent. There is far more urgency to the rhythms here - Strauss’s writing for the voice often paralleling the text itself in a far more descriptive and visual way. The impact that both Damrau and Deutsch brought to this felt as if both were painting the music with brushstrokes rather than simply singing or playing the notes - trees bent in the breeze, a brook babbled. ‘Mädchenblumen’, a set of four lieder in which the singer is metaphorically transformed into a garden of flowers, can sometimes seem a touch monochrome in performances. These are songs that stretch the imagination, songs which ask a soprano to walk a tightrope between simple sentimentality and deeper thinking. Strauss certainly doesn’t make life easy for his singer launching into the first song ‘Kornblumen’ without any piano introduction whatsoever. If Damrau was fractionally behind Deutsch here she more than made up for this by managing the long, even tortuous, first phrase so well. ‘Mahnblumen’ fizzed, with Deutsch especially displaying a lightness in the piano trills. With ‘Efeu’ the dynamic changes again. In a great performance of this song you want singer and pianist to intertwine with one another, the phrasing to both feel mysterious but borne of a single, irreplaceable event: “Denn sie zählen zu den seltnen/Blumen, die nur einmal blühen”. It’s exactly what we heard here, a moment of blossom that felt so very singular. With the final song, ‘Wasserrose’, we get Strauss at his most impressionist. Damrau and Deutsch rippled through the water, cadences expressed through small waves of inflected tone in the voice, with long chords on the piano that pushed Damrau to soar through them.

The Drei Lieder der Ophelia in some ways mirror the Wolf Mignon songs which Damrau had sung earlier. Taxing they may be, but they also impress with their dramatization of a character on the brink of madness and paranoia. Overwhelming in their depiction of mortality, of a death in the making, Damrau was often shattering. The huge, expansive leaps in the voice, the lurching between moments of sanity and the impending doom-laden hysteria and psychosis which will result in her impending drowning, they were visceral - like a Goya painting. She never held back for a moment in vocalising the existential crisis facing Ophelia. If the theme of water in her earlier Strauss had focused on its natural beauty, its movement, here the darkness in the voice, so often lacking in the Liszt, was elemental.

There were three encores - Liszt’s ‘es muss ein Wunderbares sein’, and Strauss’s ‘Nichts’ and ‘Morgen’. In a sense, ‘Nichts’ came closest to Damrau’s Bavarian roots - and the legato she displayed was exemplary. ‘Morgen’ was both fragile - rather as it should be - but also inhabited by a glorious pathos in which Damrau scaled down her voice to make the song seem almost endless.

Diana Damrau’s second concert as part of her Strauss residency consisted of a single work, his Vier Letze Lieder accompanied by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra under Mariss Jansons. I think that even if you accept that some of the works for voice and piano which Strauss subsequently orchestrated (and which Damrau had included in her first recital) - such as ‘Cäcilie’ and ‘Morgen’ - are superlative examples of Strauss’s mastery as an orchestrator none quite rival the sheer scope, or beauty, of the four songs which Strauss wrote in 1948. Few singers in my experience of hearing this work in the concert hall seem to manage to make all four songs work - though perhaps Felicity Lott has come closest. Damrau didn’t quite achieve this either - and nor did you always really feel a sense of deep and profound involvement in her singing of them.

This was one of those performances which did have moments of greatness - but it was also one which leaned heavily the other way. ‘Frühling’, so often the song which causes sopranos the most problems, was extremely fine mainly because Damrau’s more lyrical voice is so ideal for it. The sense that this music had momentum was inescapable - though Jansons had set a very fleet tempo to begin with in the strings and woodwind which Damrau was in part forced to follow. There was undeniable sweep to the voice, so when she soared above the orchestra at the end of the first stanza (‘von deinem Duft und Vogelsang’) the purity of her sound became more apparent. Likewise, there was little effort required to sustain that wonderfully ethereal extended note on “Gegenwart” which closes the song. The more autumnal mood of ‘September’ proved elusive for Damrau, not helped by a lack of poise, with much of the song’s quivering inflections coming from the orchestra’s woodwind and horns - indeed the first horn’s wonderfully played solo in the final bars seemed to dramatize Hesse’s solemn, hymnal text so much more exquisitely.

‘Beim Schlafengehen’, as in so many performances of these songs, was where this performance might have proved uneven - but it shifted into something rather special. The expectation that the voice might be rather light was misplaced mainly because Damrau has such an innate ability to think beyond the words themselves. There was considerable art on display here, as well as a beautiful technique. As with so much of her Strauss and the Wolf in her first recital, what made ‘Beim Schlafengehen’ so deeply impressive was the emotional context in which she placed this Hesse poem. The elegant way in which she managed the hugely long phrases, the impeccable pronunciation and the (mostly) unbroken lines were flawless. If she didn’t quite manage to sustain the final line “Tief und tausendfach zu leben” in a single breath without breaking the phrase at “zu” (but almost no soprano is able to do this) we were compensated with a glowingly lengthened final note on “leben” that was thrilling (and all too often abbreviated in some performances).

‘Im Abendrot’ worked too, largely because Damrau is a singer who understands that what Strauss what trying to convey in this final song is the simplicity of love. Again, the phrasing was impeccable - the voice lush enough against the orchestral backdrop but able to ride effortlessly above it, and at times merge into it. It was a magnificent ending to a performance that had unevenness, but moments of inspiration which showed such depth and beauty.

I have often found Mariss Jansons to be an uneven conductor - even a rather wilful one - but his Richard Strauss is exceptional. If his accompaniment to the Strauss songs had been almost minimalist, but imbued with a sense of wonderful clarity, it came as no surprise that his performance of Ein Heldenleben should display a similar sense of brilliance. No matter how you look at this performance - from the point of view of the conducting, the interpretation or the playing - it was magnificent. The virtuosity of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra is in many ways in a class of its own - at a famous, and utterly memorable, performance of Ein Heldenleben given at the Proms in 2004 under Jansons, the orchestra played on a blacked-out stage much of the Battle Scene when the lights in the hall malfunctioned. No such problem happened during this Barbican concert but the brilliance of the orchestra, that sumptuous sound, the expressive range of its principals leaves an unforgettable impression on the listener.

Ein Heldenleben can sometimes seem an over-long and densely orchestrated work but Jansons has a gift for making this masterpiece seem neither. The clarity he brings to it is quite remarkable, in fact. Rarely have I heard the harps play with such definition in this piece - and the characterisation he asks of the woodwind is stunning. Whole desks of flutes, clarinets, oboes and bassoons are voiced - not simply played as instruments. Strauss is so specific in what he demands of his players it often requires an exceptional orchestra to bring if off and so you get the shriek of a piccolo, the snake-like hiss of a cymbal or the arrogance of some of the lower brass. The solo horn - played here by Eric Terwilliger - was dazzling, with breath control that was effortless. That beautiful lower string sound, the very foundation of this orchestra on which everything else is built, is like crushed velvet. That searing love music which Strauss writes for ‘Der Helden Friedenswerke’ and ‘Der Helden Weltflucht und Vollendung’ has rarely sounded so intense or voluptuous when played by the Bavarian strings, with soaring horns playing meltingly above them. Dynamics are so accurate that you can imagine every detail of this vast score in your mind - and Jansons’s control over the orchestra is absolute. Radoslaw Szluc’s solo violin was so beguiling you couldn’t but be entirely hypnotised by the playing.

One anomaly with Janson’s performances of Ein Heldenleben - and it’s been one ever since I can remember him conducting this work - is the insertion of two unmarked timpani strokes in Strauss’s score. The first (in my ancient Leuckart/Leipzig edition of the score) occurs just before M.93 at the Im Zeitmass marking and the second in the very final bars of the work when the timpani should fade from a ff to a p . I can’t think of another conductor - going as far back as Toscanini and Rodzinski in the 1940s - who does this. I think most listeners scarcely notice it - and in a performance as exceptional as this one was one can overlook this intervention.

These two concerts were largely events of some stature, placing Strauss’s vocal works in a wider historical perspective. There were flaws here and there, but the quality of the singing and, in the second concert, the brilliance of the Bavarian orchestra made for two events that were entirely memorable. Diana Damrau will return to the Barbican in March to complete this Strauss series when she will sing the closing scene fromCapriccio and give the world premiere of a new work, The Hidden Place, by Iain Bell.

Marc Bridle

Diana Damrau (soprano) and Helmut Deutsch (piano)

Franz Liszt: ‘Der Fischerknabe’, ‘Die stille Wasserrose’, ‘Es war ein König

in Thule’, ‘Ihr Glocken von Marling’, ‘Die Loreley’; Hugo Wolf: Vier Lieder der Mignon; Richard Strauss: ‘Einerlei’, ‘Meinem

Kinde’, ‘Ständchen’, ‘Mädchenblumen’, Drei Lieder der Ophelia,

‘Der Rosenband’, ‘Wiegenlied’, ‘Cäcilie’

16th January 2019, Barbican Hall, London

Diana Damrau (soprano), Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Mariss Jansons (conductor)

Richard Strauss: Vier Letze Lieder, Ein Heldenleben

26th January 2019, Barbican Hall, London

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Diana_Damrau_Helmut_Deutch_Barbican_0463%20%281%29.jpg

image_description= Diana Damrau’s Richard Strauss Residency at the Barbican

product=yes

product_title=

product_by=A review by Marc Bridle

product_id=Above: Diana Damrau and Helmut Deutch

Photo credit: Peter Meisel

January 27, 2019

De la Maison des Morts in Lyon

These seven performances at the Opéra de Lyon wrap up the run of the Warlikowski production of From the House of the Dead that started last spring at London’s Covent Garden and continued in the fall at the Brussel’s Monnaie. Veteran bass Willard White has remained the prisoner Goriantchikov, Warlikowski’s protagonist for the full run as has Czech tenor Stefan Margita (San Francisco Opera’s Loge) as the prisoner Luka. Both artists are veterans of the 2007 Patrice Chéreau Aix Festival production also seen at the Metropolitan Opera in 2009.

Note that spellings of the Russian names have been Anglicized for this review.

It is ironic that black, “veteran” (the critical adjective for the past 20 years) bass White is both Chéreau and Warlikowski’s choice for the only prisoner to be freed from the horrors of modern penal servitude. For Chéreau it was a release from a physically detailed world of drudgery and degradation and suffering, for Warlikowski the prisoner’s release is a metaphorical death, the abandonment of a vibrant, intense, and principled world in which wounded human souls can truly soar. Warlikowski with conductor Pérez find, finally, the essence of Janacek’s most forgiving line “a divine spark (a soul) shines in every being” and it was an emotionally and intellectually thrilling, in fact mesmerizing conclusion to this evening of unrelenting brutality.

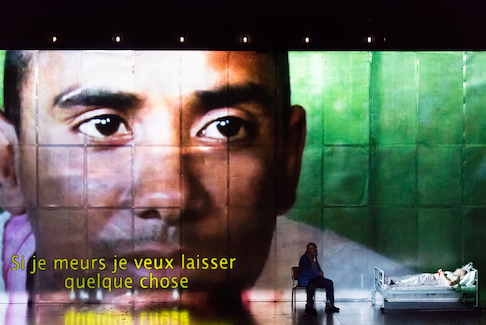

Warlikowski inaugurates his From the House of the Dead with a video of the late French philosopher Michel Foucault musing about justice and the police. He speaks over Janacek’s introductory music, the intense pace of concept and the inflection of the French is exponentially enlivened by Janacek’s already boiling motives. Janacek then drives a commanding musical climax to which the video expands the monumental gates of a soaring castle — and it is a prison!

Willard White as Goryantchikov (far left), Nicky Spence as the Fat Prisonor with Ladislav Elgr as Shuratov (center)

Willard White as Goryantchikov (far left), Nicky Spence as the Fat Prisonor with Ladislav Elgr as Shuratov (center)

A basketball court is revealed, a black player (a “pro” equivalent) dribbles and shoots a basket, among the prisoners who enter are four break-dancing acrobats (of the various skin tones that populate Western prisons) who project an unbridled spirit of freedom in their movement and in their energy, a canny take on the wildness of the Janacek score. A fight breaks out, the basketball player is wounded. We understand that the basketball player is Dostoevsky’s taunted eagle as we know that an eagle is a visual epithet of freedom.

The player will remain in a wheelchair until the final moments of the opera when he stands, shoots the ball and misses, then he takes it to the rack. Blackout.

Unnamed South African gangster (video), Willard White as Goryantchikov, Pascal Charbonneau as the wounded Alyeya

Unnamed South African gangster (video), Willard White as Goryantchikov, Pascal Charbonneau as the wounded Alyeya

Warlikowski separates the acts of the opera with a video from American film director Teboho Edkins’ Gangster Backstage in which a black South African gangster (a real gangster) muses during the musical silences about death, knowing that he wishes a legacy and that legacy might be, he imagines, saving a small boy from danger. We know now why the prisoner Goriantchikov (Willard White) will teach the young prisoner Alyeya to read and write, his legacy and gift to the spirited, truly human world that he must leave. And why he is the opera’s protagonist though he has very little to say or sing.

Warlikowski’s frenetic intellectual and physical world is deeply embedded into the continuum of Janacek’s sonic world, a world in which stories are told — Luka who stabbed the abusive commander of his prison, Skuratov who shot the rich man his mistress married, Shapkin who robbed a rich man and was tortured, and finally Shishkov who murdered his wife because she dishonored him.

Finally, more than the merely recounted violence, Shishkov elevates Janacek’s narrative opera to action — Shishkov resolutely murders Luka who he has learned is the man who had falsely denounced his new wife as unchaste. Janacek’s continuum hammers Shishkov’s revenge and his remorse, and the bravado and regret of the other raconteurs. Shishkov’s action is finally release. Violence and brutality redeemed. And Janacek drives the pathos ever deeper in the Old Prisoner’s epithet of the dead Luka, “he too had a mother.”

That Warlikowski’s plays (Kedril and Don Juan and The Lovely Miller’s Wife) within Janacek’s play added gratuitous grotesquery and violence to his prison world can be attributed to blind, probably necessary adherence to the dictums of “regietheater.” Unfortunately these attributes also became boring, detracting from the honest, effective intellectualism of the Warlikowski concept.

Lyon’s Opéra Nouvel (named after it’s architect, Jean Nouvel) offers a very present, very bright acoustic. The Opéra de Lyon’s fine orchestra was well rehearsed and poised to deliver. Conductor Pérez, new to the production, was able to exploit (to the hilt) the quite detailed urgencies of the Janacek’s orchestral continuum, giving Warlikowski a musical force to well support the overwhelming physical and intellectual energy emanating from the stage.

From which there had been no escape. That final basket was deeply felt liberation.

Much of the sterling cast survives from the Covent Garden premiere, including the Luka of Stefan Margita and the Skuratov of Ladislav Elgr. Karoly Szemeredy was new to the production as a truly riveting Shishkov (he was Warlikowski’s Captain in last summer’s The Bassarids at Salzburg), as was the Shapkin of Dmitry Golovnin.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Alexandre Petrovitch Goryantchikov: Sir Willard White; Alieïa: Pascal Charbonneau; Filka Morosov (Louka Kouzmitch): Stefan Margita; Le grand forçat (prisoner): Nicky Spence; Le petit forçat / Le forçat cuistot / Tchekounov: Ivan Ludlow; Le commandant: Alexander Vassiliev; Le vieux forçat: Graham Clark; Skouratov: Ladislav Elgr; Le Forçat ivre: Jeffrey Lloyd‑Roberts; Le forçat jouant: Don Juan et le Brahmane / Le forçat forgeron: Ales Jenis; Un jeune Forçat: Grégoire Mour; Une prostitiuée: Natascha Petrinsky; Kedril: John Graham-Hall; Chapkine: Dmitry Golovnin; Chichkov / Le pope: Karoly Szemeredy; Tcherevine / Une voix de la steppe: Alexander Gelah; Un garde: Brian Bruce; Un garde: Antoine Saint-Espès. Orchestre et Chœurs de l’Opéra de Lyon. Conductor: Alejo Pérez: Mise en scène: Krzysztof Warlikowski; Décors et costumes: Malgorzata Szczęśniak; Lumières: Felice Ross; Chorégraphie: Claude Bardouil; Vidéo: Denis Guéguin; Dramaturgie Christian Longchamp. Opéra Nouvel, Lyon, France, January 23, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dead_Lyon4.png

product=yes

product_title=From the House of the Dead in Lyon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Karoly Szemeredy here as the bearded Orthodox pope (later he is Shishkov), Stefan Margita as Luka (far right in red) [All photos copyright Stofleth, courtesy of the Opéra de Lyon]

January 26, 2019

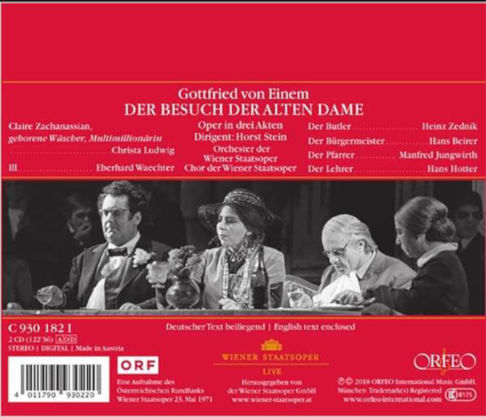

A First-Ever Recording: Benjamin Godard’s 1890 Opera on Dante and Beatrice

Many recent Godard recordings have been made possible with support from the Center for French Romantic Music, located at the Palazzetto Bru Zane (Venice).

What Godard’s several operas are like as a whole, though, has been hard to guess. The only number from any of them to survive through the years was a tenor aria, entitled Berceuse, from Jocelyn. That lovely lullaby has been recorded by an astonishing range of singers, including Bing Crosby (with, yes, Jascha Heifetz) , Plácido Domingo (with Itzhak Perlman), and my favorite: the Belgian tenor André d’Arkor, recorded in 1930 (and including, for once, the marvelous introduction and recitative).

Now a Godard opera, Dante—an imaginative tale about the poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) and his beloved, Beatrice—has been committed to disc, and in a first-rate performance . (Click here for a video containing some excerpts from the work.) I really had little idea what to expect. Yet what greeted my ears was one of the most confidently written and stylistically consistent operas I have recently encountered. The work’s basic manner might be compared to that of Gounod, but I was led to think at times also of Saint-Saëns’s Samson et Dalila and of some passages in middle Verdi. A few moments reminded me of Tchaikovsky (prelude to the final scene) and Musorgsky. But this only goes to show that Godard took solid models and that they worked well for him.

Samson (with its magnificent choruses of Hebrews and Philistines) occurs to me especially when I listen to Act 1, which consists in large part of big, oratorio-like choral tableaux, involving the struggle between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines in Renaissance Florence, and the question of whether Dante will be voted to become the city’s political leader. A direct influence of one opera on the other is perhaps unlikely, given that Saint-Saëns’s masterwork went unperformed in France until 1890, two months before the premiere of this opera. Still, Godard may have managed to see a score of Samson in the thirteen years since the its premiere in Weimar (1877).

Despite the heavy presence of chorus in Act 1, there are also extended, stirring solos (quasi-arias) for two of the main characters, Dante and Beatrice. Dante’s can be heard and seen on YouTube. The beginning of Act 2 brings a similarly gratifying solo scene for the third main character, Simeone Bardi. The latter is (as operatic tradition demanded) a baritone and stands in the way between the somewhat idealized lovers, who are of course a soprano and tenor.

(Bardi loves Beatrice and is already betrothed to her when the opera starts, thus setting up the major plot-conflict. The fourth major role is Gemma, a confidante of Beatrice who, for further complication, is in love with Dante.)

Picking up the plot where I left it: in the middle of Act 2, Dante and Beatrice get to have a passionate love duet . The act ends with an event that is historically accurate, namely the invasion of Florence by the French, who condemn Dante to exile. Bardi consigns Beatrice to a convent. Act 3 escapes history entirely. Here Dante wanders in the mountains, falls asleep, and has two dreams: first of Hell, then of Heaven. In short, Dante’s frustrated love is shown as inspiring the Inferno and Paradiso sections of his literary masterpiece, the Divine Comedy. (The genre of opera, with its love of excess in either the negative or positive direction, clearly left little room for a middle-of-the-road Purgatory dream.)

The two dream scenes contain much skillful and varied writing for orchestra and chorus, bringing the work, again, very close to oratorio. Indeed, the portrayal of Hell was so powerful (great opportunities for the brass!) that I feared that Heaven would be a disappointment, but I should have known better from a composer who wrote programmatic and “descriptive” symphonies (“Gothic,” “Oriental,” “Legendary,” and one based on the life of Renaissance poet Torquato Tasso), some of which incorporate solo and choral singing. The Heaven dream is of course colored by traditions of French religious music (well handled by Godard), but then links up with the main plot by allowing Dante to see an apparition of Beatrice, who—in eloquent musical phrases—expresses confidence in his ability to complete his epic.

In Act 4 (back in real life), Bardi, having agreed to give Beatrice up, leads Dante to her, but by this point she is sick and dying. She and Dante have a final love duet, which brings back material from the one in Act 2, and she repeats words that Dante had heard her voice uttering in the midst of the Heaven dream. Beatrice dies, and Dante commits himself to completing his literary work in her memory.

All of this would not perhaps amount to much if the music weren’t good. But it is better than good: clear in intent, melodically memorable, secure in harmony, and full of inventive accompanimental figures. Most gratifying are the short orchestral commentaries that punctuate the work: not just preludes before scenes but also statements in between phases in the action or between declarations by one character and responses by another. The opera repeatedly shows a deft ability to integrate the symphonic and the dramatic, in ways very different from the procedures advanced by Wagner. Godard is said to have wanted to have nothing to do with Wagnerianism. (He was of Jewish origin and utterly opposed to Wagner’s antisemitic polemics.)

The performance is splendid. The Palazzetto has here re-hired two of its most successful vocalists from previous volumes of their “French Opera” series. Gens is perfection itself as Beatrice. Montvidas (from Lithuania) makes a plangent Dante, secure in loud passages and especially touching in soft, doubt-filled ones. (Gens and Montvidas were superb as the central figures in Félicien David’s Herculanum, and Gens revealed a particularly wide range of emotions in Saint-Saens’s Proserpine.)

The big new discovery for me is the alto, Frenkel (from Israel), who commands the necessary low register for the role. Baritone Lapointe, as Bardi, lacks strength in his low notes. In his middle register, the vibrato can get a bit wide and slow. Lapointe is splendid, though, when things go high. Andrew Foster-Williams does a capable job as an Old Man and as the Ghost of Virgil (who guides Dante on the tour of Hell and Heaven). His voice is not ideally steady, but perhaps one excuses this somewhat because one of the characters is aged and the other is a vision rather than flesh and blood. Diane Axentii sings well in the role of “a schoolboy,” who offers a strophic ode to the greatness of Virgil in Act 3 (shortly before the spirit of the great writer arrives in order to guide Dante on a tour of Hell and Heaven).

The Munich orchestra and chorus under Schirmer respond with total assurance, as if they have known the work for years. The one weakness, I felt, was a certain start-and-stop quality in Act 4. I had just finished reviewing Berlioz’s Les Troyens and noticed how much more adroit Berlioz was at ensuring continuity from one section of a scene to the next (i.e., not requiring much adjustment on the part of the conductor). Perhaps Act 4 would flow more persuasively if the pauses between musical numbers could be kept shorter. I did not notice any such problem in Acts 1-3. This is the kind of problem that gradually get “fixed” (in both senses of the word: repaired and also standardized) as an opera finds its way into the repertory. For example, conductors make all kinds of unmarked but by-now-traditional tempo shifts in middle Verdi to help a work be fully effective. I noticed this while listening to a recent and relatively conventional live recording of Il trovatore from the Macerata Festival: back-and-forths between characters are often underscored by pointed adjustments in tempo (from conductor Daniel Oren) that suit each character’s current emotional state and that thus integrate the dramatic arc into the sung and played music.

The Palazzetto’s scholarly team prepared the score and parts and commissioned and edited the first-rate essays in the accompanying hardcover book.

Imagine what a stage director and designer could do with the Heaven and Hell visions of Act 3! Let’s just hope they don’t try to update or alter the onstage action in the rest of the opera. Perhaps they could even do something that today might be considered daring: set the opera in fourteenth-century Florence and try to evoke the afterlife, in Act 3, in ways that would have suited the era of Dante himself, or of the composer and librettist, rather than how we might imagine them today. (Late bulletin: a stage production is scheduled for February 2019 at the opera house in the French city of Saint-Etienne, about an hour from Lyons.)

Or perhaps the work is best suited to performance “in concert” (i.e., without sets or costumes). That way, each audience member can imagine a Hell and a Heaven that speaks to him or her.

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide . It appears here by kind permission of ARG.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and the second is also available as an e-book. His reviews appear in various online magazines, including The Arts Fuse , NewYorkArts , and The Boston Musical Intelligencer .

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dante_front.jpg image_description=Ediciones Singulares ES1029 product=yes product_title=Benjamin Godard: Dante (opera) product_by=Véronique Gens (Beatrice), Rachel Frenkel (Gemma), Edgaras Montvidas (Dante), Jean-Francois Lapointe (Simeone Bardi), Diana Axentii (schoolboy), Andrew Foster-Williams (an old man, ghost of Virgil), Andrew Lepri Meyer (herald). Munich Radio Orchestra and Bavarian Radio Chorus, conducted by Ulf Schirmer. product_id=Ediciones Singulares ES1029 [2 CDs] price=$30.09 product_url=https://amzn.to/2DBSGpw

January 24, 2019

La Nuova Musica perform Handel's Alcina at St John's Smith Square

Were the expectant punters enticed by promise of a ‘prelude’ to the 2019 London Handel Festival - which runs from 27th March to 29th April - sung by a superb cast of soloists, or by the appearance of Joanna Lumley as the ‘narrator’ reading June Chichester’s recitative-replacing inter-aria text?

For, the evening’s performance was an “experiment”, one which, according to Katie Hawks’ programme article, “dipped in the waters of authenticity” by following the practice of German opera houses in Handel’s day of singing the recitatives of opera seria in the native language, while retaining the original Italian text of the arias. Here, though, the Italian recitative was done away with altogether, replaced by spoken English summaries which were “intended to convey the drama better”.

Certainly, the romantic entanglements of Alcina do require intricate unravelling. The opera premiered at Covent Garden in April 1735 during Handel’s first season at the Theatre Royal and presents episodes from Ariosto’s Orlando furioso in which the eponymous Sorceress lures heroes to her enchanted island, quickly becomes disenchanted with their merits and charms, and so casts spells which turn her former lovers into animals and trees, rocks and streams. The virtuous Bradamante - disguised as her brother Ricciardo - arrives on the island with her friend Melisso to rescue her fiancé, the bewitched Ruggiero. Complications ensue when Morgana, Alcina’s sister who is loved by the Sorceress’s steward, Oronte, falls in love with ‘Ricciardo’. Her jealousy aroused, Alcina sets out to turn the latter into a wild beast. Magic rings and Ruggiero’s moral awakening intervene, and the Sorceress finds herself suffering the afflictions of true love.

This drama, somewhat absurd and sometimes confusing, is presented in the recitatives; and, even if one does not understand the sung language, one can appreciate the tenor of the situation and action, the changing nature of the relationships, the pace of the drama. The recitatives provide the contexts for the emotional effusions of the arias. And, they provide contrasts of musical colour. Take them away and you’re left with the jewels without a chain to thread them together.

Joanna Lumley and William Berger. Photo credit: Nick Rutter.

Joanna Lumley and William Berger. Photo credit: Nick Rutter.

Descending from her armchair-throne behind the instrumentalists, Joanna Lumley read June Chichester’s text - which often seemed simply to summarise the arias - with judicious lip-curling, eye-brow raising wryness. Occasionally she addressed a singer directly, at other times she re-positioned a music stand in advance of an aria. But, despite the clarity and nuance of her delivery (was amplification really necessary?), the musico-dramatic focus and momentum drooped during the spoken text. Conductor David Bates worked tremendously hard to drive the drama forwards and drew playing of tremendous rhythmic élan and textual clarity from La Nuova Musica. But, the performance didn’t have the sort of dramatic fluency that can carry the listener through the admitted irrationalities of some of the libretto’s romantic muddles and misunderstandings. I wasn’t convinced that the ‘experiment’ clarified the action, and the omission and re-ordering of some arias did not help in this regard.

John Caird (who is an Honorary Associate Director of the RSC and Principal Guest Director of the Royal Dramatic Theatre, Stockholm) was billed as the ‘director’, but I struggled to discern his contribution. The singers, most of whom used scores, simply did what good singers do; that is, respond naturally to the dramatic situation through voice, gesture, manner. They sang their arias in turn, sometimes standing amid the instrumentalists, sometimes behind them, often seated - unfortunately so in the latter case, given the poor sight-lines in SJSS. Even a simple lighting design would have enhanced our sense of the mystery and menace of Alcina’s fantastical realm, of the Sorceress’s struggle to control her victims and to understand the growing affections of her own heart. And, her devastation when both her magic powers and her former lovers, restored to human form, have vanished, leaving her alone and bereft. There was an elaborate display of candles above the seated singers at the rear, but it wasn’t clear what this was supposed to represent or evoke.

Anaïs Chen and Patrick Terry. Photo credit: Nick Rutter.

Anaïs Chen and Patrick Terry. Photo credit: Nick Rutter.

Fortunately, the musical performances more than made up for these frustrations. Particularly impressive was countertenor Patrick Terry who conveyed both Ruggiero’s initial boyish need for reassurance and affection, and his subsequent self-knowledge when he comes to appreciate the emptiness of his earlier happiness. Handel’s original Ruggiero, the castrato Giovanni Carestini, so the story goes, was dissatisfied with the simplicity of the plaintive ‘Verdi prati’ - in which Ruggiero recognises that the beautiful green island is an illusion which will soon dissolve into a barren reality - and sent it back to Handel, whose riposte was that if Carestini didn’t sing the aria he would be paid nothing. I admired Terry’s singing when I first heard him perform in the Kathleen Ferrier Awards Final in 2017 (when he won the Song Prize), and the fullness of his tone and smoothness of line that I noted on that occasion have grown even more beguiling. ‘Verdi prati’ was the emotional heart of this performance, in which Ruggiero’s regret was enhanced by leader Anaïs Chen’s exquisite violin solo, but Terry was just as stirring in ‘Sta nell’Ircana’ - to which the natural horns of Anneke Scott and Joseph Walters offered a vibrant, colourful complement - phrasing the exuberant runs stylishly and powering sonorously to the final cadence.

Madeleine Shaw, Rebecca Bottone and Leo Duarte. Photo credit: Nick Rutter.

Madeleine Shaw, Rebecca Bottone and Leo Duarte. Photo credit: Nick Rutter.

Rebecca Bottone was a characterful Morgana, her upper register shining. Morgana’s initial mischievous flirtatiousness was engagingly embodied by oboist Leo Duarte’s juicy obbligato, while the expressive phrasing of Morgana’s later plea for forgiveness was complemented by the gracious muscularity and plaintiveness of John Myerscough’s cello obbligato. Not surprisingly, Christopher Turner’s Oronte could not resist his wayward beloved’s entreaties, the nuanced legato line of his subsequent ‘Un momento di contento’ expressing the assuagement bestowed by true love. As the hollow-hearted Sorceress, Lucy Crowe sang with characteristic liquefaction and limpidity, but while Crowe’s elegance was unwavering, at times I found her tone rather ‘white’, and not fully expressive of Alcina’s wide-ranging emotions.

As Bradamante, Madeleine Shaw conveyed a feminine warmth beneath ‘Ricciardo’s’ vengeful anger, and baritone William Berger - who, like Terry, sang from memory - projected Melisso’s single aria well, displaying strength at the bottom of his range, and rising easily with even colour. I look forward to hearing both Berger and Terry again when they join the cast of Berenice, at the ROH’s Linbury Theatre, during the forthcoming London Handel Festival ‘proper’.

This performance of Alcina was warmly appreciated by the SJSS audience, and certainly whetted the appetite for this year’s LHF. But, oddly, the real ‘enchantment’ on this occasion occurred during the instrumental obbligatos, which were performed from memory with the solo players moving forward to participate in the ‘action’; here was real musical magic.

Claire Seymour

La Nuova Musica: Alcina

Alcina - Lucy Crowe, Ruggiero - Patrick Terry, Morgana - Rebecca Bottone, Bradamante - Madeleine Shaw, Ornote - Christopher Turner, Melisso - William Berger, Narrator - Joanna Lumley, Director - David Bates, Director - John Caird.

St John’s Smith Square, London; Tuesday 22nd January 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Alcina%20rehearsal.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Alcina, La Nuova Musica (London Handel Festival) product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: La Nuova Music at St John’s Smith Square (in rehearsal)Photo credit: Nick Rutter

January 23, 2019

Ermonela Jaho is an emotively powerful Violetta in ROH's La traviata

Conductor Antonello Manacorda didn’t inject much life or spirit into the overture: uncharacteristically, the ROH Orchestra seemed drained of colour, the cellos neither bloomed nor ached, and tempi were sluggish. The lacklustre opening certainly wasn’t a case of ‘aging’. Eyre’s production may be 25-years-old but it’s still handsome in conception and design, Bob Crowley’s sets sculpting gracious spaces.

Violetta’s Parisian apartment has a stylish grandeur which brings to mind the art deco entrance hall at Eltham Palace - the overarching dome, through which light seems to burst, highlighting the beautiful veneer and marquetry. Subsequently, the Act 2 rural retreat exudes classy minimalism and artistic taste, while the crimson is still pulsing in the gambling scene, voluptuously lit by Jean Kalman who bathes his frolicking gypsy girls and strutting matadors in rich hues of complementary red and green. Then, finally, the vivacity is blanched and bleached for the death scene, which takes place in a grey, bare room dominated by a huge slanting mirror, its glass blackened and rotting - a photo negative of Violetta’s inner physical decline.

These are images and spaces which conjure passion, excitement and fear. And, given the strong cast assembled it was a surprise that there were few genuine on-stage emotional frissons in Act 1. There was some fine singing but even the redoubtable ROH Chorus, while as vocally secure as always, seemed rather staid and sturdy. Indeed, though on previous occasions I’ve not been troubled by the way the set often pushes the cast and Chorus forwards to the fore-stage, throughout this performance there seemed to be a disappointing predominance of stand-and-sing non-choreography.

Eyre’s production has had countless revivals with numerous divas in the title role. The Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho first stepped into Violetta’s shoes at Covent Garden when she deputised at short notice for an indisposed Anna Netrebko in 2008, and she returned to the role here in 2010 and 2012. Internationally, Violetta Valéry has become one of her most successful roles. But, in Act 1 Jaho and Charles Castronovo - who was Jaho’s Alfredo in Paris last autumn - seemed to be singing ‘at’ rather than ‘to’ each other: there was more emotional spark from the central ice sculpture around which the revellers swirled.

Ermonela Jaho (Violetta). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Ermonela Jaho (Violetta). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

I wondered if I’d simply seen too many Traviatas of late, after performances by Opera Holland Park , the Glyndebourne Tour and Welsh National Opera in the last few months. But, I think my initial disenchantment has a different root. Jaho is a superb dramatic communicator, but she lacks the sort of lyric sumptuousness that can convince us of Violetta’s captivating allure - such as is required in ‘Ah, fors’ è lui’ and ‘Sempre libera’, which Jaho approached somewhat tentatively. Conversely, the more infirm and fractured Violetta becomes, the more credible is Jaho’s communication of physical and mental vulnerability through vocal slenderness - her frailty, of body and utterance, is compelling. We might expect a singer to use colour and muscular strength to shape a line, phrasing and projecting to convey character; Jaho’s expressive impact seems to be achieved by the inverse. Her tone is rather monochrome, but she can withdraw her soprano until it is the merest whisper - the scant thread which holds Violetta in this world, as the afterlife beckons. And, it is breathtakingly beautiful and touching at times, if occasionally repetitive.

That said, Violetta’s Act 3 demise was heart-breaking. Every tremor, every brief flame, was piercingly emotive. If her Act 2 exchanges with Alfredo’s father were less successful, than that is partly owing to Igor Golovatenko’s inflexible phrasing and overly pressing sound: the tone was strong and true, but it was unwaveringly loud, and this Giorgio Germont came across as a heartless patriarch whose condescension and cruelty - his iron-rod back, and iron-hard delivery - simply overwhelmed Jaho’s brittle delicacy. Golovatenko was more dramatically effective in his subsequent exchanges with Castronovo. And the latter, if he seemed to be lacking the party spirit in the Act 1 brindisi, was chillingly vicious in his humiliation of Violetta in the gambling scene, conveying a truly hurting heart battling with spitefulness.

Charles Castronovo (Alfredo), Ermonela Jaho (Violetta), Catherine Carby (Annina), Simon Shibambu (Doctor Grenvil). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Charles Castronovo (Alfredo), Ermonela Jaho (Violetta), Catherine Carby (Annina), Simon Shibambu (Doctor Grenvil). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Overall, though, this was effectively a one-woman show. There were consistent, well-considered performances from Catherine Carby as Annina, and Simon Shibambu as Doctor Grenvil. And, the two Jette Parker Young Artists also impressed: Aigul Akhmetshina was a vivacious Flora, while Germán E. Alcántara showed confidence and presence as Baron Douphol.

But, it was Jaho who, in Acts 2 and 3 at least, commanded and demanded our attention. If a wrenching portrait of physical and psychological demise is what you’re after, this is a Traviata for you. There are, however, two casts for this production , and Angel Blue and Plácido Domingo may throw some different ingredients into the mix.

Claire Seymour

Verdi: La Traviata

Violetta Valéry - Ermonela Jaho, Alfredo Germont - Charles Castronovo, Giorgio Germont - Igor Golovatenko, Annina - Catherine Carby, Flora Bervoix - Aigul Akhmetshina, Baron Douphol - Germán E Alcántara, Doctor Grenvil - Simon Shibambu, Gastone de Letorières - Thomas Atkins, Marquis D'Obigny - Jeremy White, Giuseppe - Neil Gillespie, Messenger - Dominic Barrand, Servant - Jonathan Coad; Director - Richard Eyre, Revival director - Andrew Sinclair, Conductor - Antonello Manacorda, Designer - Bob Crowley, Lighting designer - Jean Kalman, Director of movement - Jane Gibson, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Monday 21st January 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Charles%20Castronovo%20as%20Alfredo%20Germont%20and%20Ermonela%20Jaho%20as%20Violetta%20Val%C3%A9ry%20%28c%29%20Catherine%20Ashmore.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=La traviata, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id= Above: Charles Castronovo as Alfredo Germont and Ermonela Jaho as Violetta Valéry

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore

January 22, 2019

Garsington Opera’s 30th anniversary season: four new productions including an Offenbach premiere

The season culminates

with concert performances of Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610,

celebrating the start of a partnership with The English Concert. The season

runs from 29 May to 26 July.

Garsington Opera remains committed to engaging great singers from around the world as well as showcasing the best talent from the UK. They are joined by the Garsington Opera Chorus and Orchestra, and for the performances of The Bartered Bride, the Philharmonia Orchestra.

The UK stage premiere of Offenbach’s little-known opera Fantasio celebrates his bicentenary year. A

beguiling tale of love and mistaken identity, it will feature Hanna Hipp, who sang Clairon in Capriccio last

season, in the role of the Jester, a melancholy,

moon-struck dreamer yearning after Princess Elsbeth, performed by Jennifer France, winner of the Critics Circle Emerging

Talent Award 2018, the Leonard Ingrams Foundation Award 2014 and praised

for her appearance as Susanna in John Cox’s legendaryLe nozze di Figaro. They are joined byHuw Montague Rendall (Prince of Mantua),Timothy Robinson (Marinoni),Brian Bannatyne-Scott (King of Bavaria) and Bianca Andrew (Flamel). Three singers, formerly on the

Alvarez Young Artists’ Programme, Benjamin Lewis (Sparck),Joseph Padfield (Hartmann) and Joel Williams (Facio) complete the cast. This fantastical

story is performed in a lively new English translation byJeremy Sams. The creative team of directorMartin Duncan and designer Francis O’Connor return after many admired productions at

Garsington Opera, and are joined by lighting designerHoward Hudson and choreographerEwan Jones. Making his Garsington Opera debut, Justin Doyle, Artistic Director of

RIAS Kammerchor

, Berlin, will conduct.

The Bartered Bride

, a celebration of Czech culture and identity, will be reimagined into the

heart of the English countryside, and will open the season.Natalya Romaniw, last seen at Garsington as Tatyana inEugene Onegin, sings the heroine Mař enka who uses all her charm and cunning to marry the man she loves

- Jeník, sung by American tenor Brenden Gunnell. The cast

includes Joshua Bloom (Kecal) last seen as Figaro (2017),Stuart Jackson (Vašek), Peter Savidge (Krušina), Heather Shipp

(Ludmila), Brian Bannatyne-Scott (Mícha),Anne-Marie Owens (Háta), andJeffrey Lloyd-Roberts (Circus Master). Lara Marie Müller, a former Alvarez Young Artist, sings

Esmeralda. Dance is at the heart of this sparkling work from the vibrant

overture to the riotous and festive polka; Jac van Steen,

who returns after his success with Pelléas et Mélisande (2017),

will conduct the Philharmonia Orchestra. The creative team

of Paul Curran (director) and Kevin Knigh

t (designer), whose production of Death in Venice (2015) was much

acclaimed, returns with Howard Hudson (lighting designer)

and Darren Royston (movement director).

Mozart's enduring masterpiece Don Giovanni will feature several role debuts including Jonathan McGovern in the title role, David Ireland (Leporello), formerly an Alvarez Young Artist, Australian soprano Sky Ingram (Donna Elvira) and Welsh tenor Trystan Llŷ r Griffiths (Don Ottavio). The cast also includes two UK debuts - Brazilian soprano Camila Titinger (Donna Anna) and Canadian soprano Mireille Asselin (Zerlina).Paul Whelan (Commendatore) and former Alvarez Young Artist Thomas Faulkner (Masetto) complete the cast. Garsington Opera’s Artistic Director Douglas Boyd conducts and former Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare CompanyMichael Boyd (director) returns to direct together withTom Piper (designer), after their success withPelléas et Mélisande (2017) and Eugene Onegin (2016) with Malcolm Rippeth (lighting designer).

The Turn of the Screw

with a libretto by Myfanwy Piper, based on the novella by Henry James, is

considered to be one of Britten’s finest stage works. The gripping story of

a young governess, performed by Sophie Bevan, sent to a remote country house to care for two children,

also features the tenor Ed Lyon (Prologue/Quint), making

his role debut. Also in the cast are Kathleen Wilkinson

(Mrs Grose) and Katherine Broderick (Miss Jessel).

Emerging American director Louisa Muller makes her UK

debut together with two-time Olivier and Tony Award-winnerChristopher Oram (designer) andMalcolm Rippeth (lighting designer). Richard Farnes, conductor of last year’s admired Falstaff, will conduct.

Celebrating the start of a new partnership, the renowned Baroque and

Classical chamber orchestra The English Concert makes its

Garsington debut playing on period instruments in three concert

performances of Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610.

They will be joined by soloists Mary Bevan,Sophie Bevan, Benjamin Hulett,Robert Murray and James Way.Laurence Cummings returns to conduct with the Garsington Opera Chorus.

Marking the end of the 30th anniversary season, on the three

concert days there will be an afternoon cricket match, tours of the Walled

Garden and Green Theatre Recitals showcasing the Alvarez Young Artists, as

well as the opportunity to visit the Getty Library.

OPERAFIRST AND FANTASIO

As part of an extensive Learning & Participation Programme, there will

be a full performance of Fantasio by the Alvarez Young Artists for

local school pupils and adults, all of whom take part in preparatory

workshops to introduce them to opera and deepen their enjoyment of the

performance.

GARSINGTON OPERA AT WORMSLEY

Opera patrons are invited to arrive from 3.30pm to enjoy the extensive gardens and Deer Park of the Wormsley Estate in the heart of the Chilterns, before performances begin in the early evening. Those arriving early can take a short trip in a vintage bus to the 18th century Walled Garden. On their return, they can enjoy traditional afternoon tea overlooking the cricket pitch, admire the spectacular views across the Deer Park and lake from the Champagne Bar, or stroll around the Opera Garden and grounds. In the long dinner interval patrons can dine in the elegant restaurant marquee overlooking the famous Wormsley Cricket Ground or they can have a picnic by the lake, in the garden or in one of the private picnic tents. Performances resume as the evening light begins to fade and end around 10.15pm. A minibus service connects with High Wycombe station, a half hour train journey from London. A short open-air recital by Alvarez Young Artists awaits Saturday patrons in the Green Theatre in the Walled Garden (weather permitting).

WIDENING ACCESS TO GARSINGTON OPERA

Garsington Opera is passionate about widening access to a young audience

and has a much sought-after GO≤35 membership scheme which offers subsidised

tickets, priority booking, free train transfers, pre-performance parties

and half price programmes.

DIARY OF EVENTS AT WORMSLEY

The Bartered Bride

- 1 29, 31 May, 6, 8, 11, 15, 20, 23, 30 June (start time 6.05pm)

Don Giovanni

-

30 May, 1, 7, 13, 24, 29 June, 3, 6, 12, 14, 18, 21 July (start time

5.45pm)

Fantasio -

14, 16, 22, 27 June, 5, 8, 11, 17, 20 July (start time 6.05pm)

The Turn of the Screw -

1, 4, 7, 13, 15, 19 July (start time 6.35pm)

Vespers of 1610 - 2

4, 25, 26 July (start time 8.30pm)

Tickets £60 - £225 including a suggested but non-obligatory donation of £70 (Vespers £30).

Public booking opens Tuesday 19 March 2019. Book online: www.garsingtonopera.org or Telephone 01865 361636.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Garsington%2030%20logo.pngJanuary 21, 2019

Vivaldi scores intriguing but uneven Dangerous Liaisons in The Hague

No wonder that, by the end of the evening, they have all defected to join the revolution. As imaginative and ambitious as their previous projects, OPERA2DAY’s latest production is a pastiche of vocal gems from Antonio Vivaldi’s operas, his Stabat Mater and Juditha triumphans, his only surviving oratorio. Sonatas and concertos provide the instrumental intermezzos. The libretto, by Stefano Simone Pintor and Serge van Veggel, is an adaptation of that fecund inspiration for plays, films, operas and ballets, Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’s 1782 epistolary novel Les liaisons dangereuses. Arias were reworded and recitatives added. Composer Vanni Moretto threaded it all together and scored the recitatives, which at times sounded more like Mozart than Vivaldi. Despite an uneven cast and a debatable finale, the production was visually entertaining and had many striking moments.

Since Vivaldi supplied the music, the setting was moved from France to Venice. Otherwise, the quintet of soloists more or less sticks to the original tale. Two jaded aristocratic ex-lovers, the Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont, casually ruin a young couple in love while chasing the real prize, Madame de Tourvel, a morally spotless judge’s wife. It all starts off light-heartedly, with much innuendo about the storming of citadels. Things turn grim, however, when Valmont unexpectedly falls in love with Marie de Tourvel and the Marquise is consumed with jealousy. Perhaps alluding to this green-eyed monster, the mixed-era costumes are in every shade of green imaginable, from wrinkled pea to deep olive, contrasting with the set’s scarlet-and-gold palatial splendor. Actors and extras play an army of servants, constantly fetching and carrying props. Van Veggel, who also directs, marshals them with droll inventiveness. When the flunkey-flogging Valmont seeks out Madame de Tourvel in church, one of his men carries in a huge cross and, like Christ on the road to Calvary, buckles under its weight. The theatrical high point is the consecutive conquests by the older couple of the Chevalier Danceny and Cécile de Volanges. Under the guise of lessons in the art of seduction, the convent graduate and her music teacher are deflowered on a canopy bed with a perfect mix of eroticism and humor. Coloratura leading to orgasm is a mainstay of Baroque opera, but Stefanie True’s Cécile atop countertenor Yosemeh Adjei’s Valmont did it in the best of taste, while warbling “Sperai la pace qual usignolo” from Orlando, finto pazzo.

True was a charming Cécile. The core of her pleasant soprano was a tad flimsy, but it rose clearly to a flute-like top. As Danceny, male soprano Maayan Licht displayed a bewildering flexibility. Apart from his unusual voice type, he had the technical proficiency to deliver the role’s musical witticisms in the most natural manner. Adjei’s highly amusing Valmont swaggered around on high-heeled boots with complete confidence, even when fornicating with a fortepiano. He sang very well, but, his voice not having the cut for the furious arias, was much more convincing in lyrical mode. Contralto Candida Guida showed plenty of temperament as the Marquise. Unfortunately, on opening night she was not in good voice. Uncertain intonation and imprecise runs marred such virtuoso challenges as “Nel profondo” from Orlando furioso. Singing with a velvety legato, mezzo-soprano Barbara Kozelj as Madame de Tourvel made her every appearance an event, including the favorite “Sposa, son disprezzata”, filched by Vivaldi from Geminiano Giacomelli. In the pit, the Netherlands Bach Society under Hernán Schvartzman were limber and expressive and gave one of the best musical performances of the evening.

The opera hops along nicely until the seventh and final scene, when swathes of spoken dialogue provide the denouement. Suddenly, we’re in a play rather than an opera. The disillusionment of the young couple when they realize they’ve been used, the Marquise humiliating Valmont, Valmont allowing Danceny to kill him in a duel—all this happens without a single sung note. No doubt this was a deliberate choice, but it felt as if the writers had lost faith in opera as narrative. Laughing hysterically, the Marquise prepares for her final ball. In a gown of iridescent raven feathers, she dances to Moretto’s arrangement of the Trio Sonata in D minor Op.1 no.12, “La Follia”. It’s the perfect soundtrack for the Marquise’s breakdown and the ancien régime collapsing all around her. Moretto’s orchestration highlights the dissonants in La Follia’s wild conclusion and the opera ends with an arresting pairing of sound and visuals, which could have done without the wordy lead-up. Instead, more great vocal stuff was called for, such as when Cécile and Madame de Tourvel both retreat to convents, the former to take the veil and the latter as a mental patient. Their lonely cries rose forlornly out of the darkness in the echo aria “L’ombre, l’aure e ancora il rio” from Ottone in villa—piercingly beautiful. Dangerous Liaisons continues to tour the Netherlands until the 16th of March. Performances are subtitled in English and Dutch.

Jenny Camilleri

Vivaldi: Dangerous Liaisons

Marquise de Merteuil: Candida Guida; Vicomte de Valmont: Yosemeh Adjei; Présidente de Tourvel: Barbara Kozelj/Ingeborg Bröcheler (February 13 and 21); Chevalier Danceny: Maayan Licht; Cécile de Volanges: Stefanie True/Emma Fekete (February 1 and 8); Victoire: Emma Linssen; Azolan: Merijn de Jong; Lahaye: Fabian Smit; Serafia: Emma van Muiswinkel; Faubourg: Luciaan Groenier. Direction and Concept: Serge van Veggel; Libretto: Stefano Simone Pintor and Serge van Veggel. Additional Music: Vanni Moretto. Set Design: Herbert Janse; Costume Design: Mirjam Pater; Lighting Design: Marc Heinz. Conductor: Hernán Schvartzman. Netherlands Bach Society. Seen at the Koninklijke Schouwburg, The Hague, on Thursday, 17th of January, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dangerous%20Liaisons.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Dangerous Liaisons, Koninklijke Schouwburg, The Hague product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=January 20, 2019

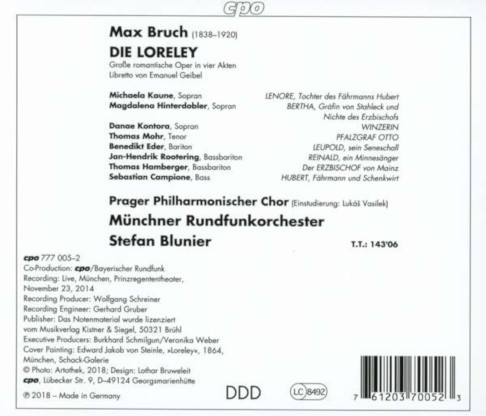

Between Mendelssohn and Wagner: Max Bruch’s Die Loreley

Bruch (1838-1920) may be best known for his Violin Concerto no 1, but this first ever recording of his full opera should broaden interest in his output as a whole. Bruch's Die Loreley is a very early work indeed, written between 1860 and 1863, and shows how the composer responded to the influences around him. The text, by eminent poet Emanuel Geibel (1815-1884), was conceived for Felix Mendelssohn, whose music Geibel loved dearly. He so identified the text with Mendelssohn that he was reluctant to give Bruch permission to use the libretto. But Bruch (in an era before copyright enforcement) was not deterred. The Mendelssohn connection is significant, because it shows the context in which the opera was written, which shapes the way in which the opera should be assessed. Far from being retrogressive, Bruch was in tune with the values of German music theatre, as represented by Mendelssohn, Carl von Weber, Heinrich Marshner (whose 1833 opera Hans Heiling addresses the Lorelei legend) and even Robert Schumann. Though Bruch's Die Loreley doesn't, understandably, have the astonishing originality of mid and late period Wagner, it can be heard as a young composer's response to the "new", heralded by Richard Wagner.

Immortalized by Heinrich Heine's poem Die Lorelei (1822) the Lorelei legend epitomizes the aesthetic of the early Romantic era, where Nature spirits inhabit idyllic landscapes where humans encounter extraordinary adventures. Seduced by beauty, mortals meet their doom. The Romantic spirit wasn't "romantic", but haunted by a sense of death, mystery and inevitable change. In Heine's words, "Ich weiß nicht, was soll es bedeuten, Daß ich so traurig bin".

In Geibel's libretto, Leonore, (sung by Michaela Kaune), daughter of a ferryman who works on the Rhine, sings a love song for a hero of her dreams, as she sits on a rock above the river. Hearing her voice, Pfalzgraf Otto (Thomas Mohr) becomes entranced, but he's due to be married the next day to Bertha the Gräfin von Staleck. Leonore is so pure that when she sings, she's accompanied by an angelic chorus who sing the Ave Maria. Leonore lives in a world of the imagination, so Geibel introduces, for contrast, Leonore's father Hubert (Sebastien Campione), the boatmen and the vintners, busy at work on the river bank. Bruch uses energetic, simple rhythms to suggest physical labour and stability, with choruses for men, women and combined voices. A procession passes by, bearing Gräfin Bertha (Magdalena Hinterdobler,) who is loved by the villagers for her kindness. Banners fly, and presumably horses prance, suggested by jaunty march.

Act II is short, but pivotal. A storm gathers and the Spirits of the Rhine rise up from the waters.; Surging figures in the orchestra evoke Mendelssohn, choral lines swaying wildly. Heartbreak has changed Leonore's personality. She calls on the Spirits to avenge her : they echo her words, leading her on. "Mein Herz versteine wie dieser Felsen!" If she cannot have Otto, her heart will turn to stone. She throws her golden ring to the Spirits and pledges herself to them if they'll enact a curse on the unwary. In Geibel's version, Leonore herself initiates the curse, and suffers for it., and the Spirits of the Rhine are both male and female. In Wagner's Der Ring der Neibelungen, the Rhinemaidens were innocents, tricked by Alberich, who placed a curse on the Rheingold. But such is the nature of art : each approach to the legend inspires new ideas.

In the Pflazgraf's castle, the wedding feast is being celebrated with cheerful choruses. A Minnesänger, Reinald (the veteran Jan-Hedrik Rootering, still in good form) sings of love and fidelity. Otto is terrified, but no-one knows why. Suddenly, Leonore materializes, singing the song of the Loreley. Otto can hold himself back no longer and claims Leonore, raving and starting a fight among the knights. The Archbishop (Thomas Hamberger) and priests accuse Leonore of witchcraft and have her sent, in chains, for trial. But she sings her defence so beautifully that all who hear it are enchanted. Otto still rages, and is excommunicated and driven away. Bertha dies of a broken heart. In Hubert's village, the boatmen and vintners mourn her. Otto sits outside the church , hearing their hymns but still cannot escape the curse. He heads back to the rock where he first encountered Leonore , begging her forgiveness, but she's no longer of his world, her lines plaintive and keening. "Zwischen dir und mir steht einfort eine dunkele Macht. The orchestra surges, and the Spirits of the Rhine well up around her. Their curse is fulfilled, and they claim her for their own, the "Köningin vom Rhein".

Given the connection between Geibel and Mendelssohn, it's almost impossible not to hear echoes of Mendelssohn in Bruch's score, though it's clear that Bruch was responding to Wagner, with echoes of Tannhäuser, and to much else popular in the period. Geibel's libretto for Die Loreley is superb, so well written that Bruch can set each scene to catch the atmosphere. The Grand Scene of the Spirits, which forms the Second Act, is quite an achievement for a composer in his early 20's. Though the opera is not a major milestone, it is well worth hearing as part of the evolution of German music theatre in this period. Stefan Bunier and the Münchner Rundfunkorchester give a rousing account, which probably won't be improved upon for some time, since the opera was only recently revived in full. A good cast all round. Kaune and Mohr are particularly impressive, she at turns meek and ferocious, malevolent and wistful, epitomizing the complexity of Leonore's character. Mohr's clear tenor rings as though Otto were a hero, which he is, in a way, since he was cursed through no real fault of his own.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Loreley_front.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Max Bruch: Die Loreley

product_by= Stefan Blunier, Münchner Rundfunkorchester, Michaela Kaune, Magdalena Hinterdobler, Thomas Mohr, Jan-Hendrick Rootering Prager Philharmonischer Chor.

product_id=CPO777 005-2 [3CDs]

price=£32.89

product_url=https://amzn.to/2CyKhBs

January 18, 2019

Porgy and Bess at Dutch National Opera – Exhilarating and Moving

Gershwin’s folk opera, with a libretto by Ira Gershwin and DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, has been accused of many wrongs–cultural appropriation, propagation of minority stereotypes, too many musical-like numbers. One can refute or accept these assertions, but Gershwin’s love for the music of the black South Carolina population, among whom he spent a whole summer composing, bursts through his scintillating score. So does his admiration for their strength in the face of adversity. The residents of Catfish Row continue to speak to new generations because they struggle with ever-relevant issues–intergenerational poverty, addiction and violence. At the same time, the solidarity within this marginalized community is uplifting. Although poor, they don’t think twice about donating money for a funeral or raising an orphaned child as their own. At the heart of this communal portrait is the disabled beggar Porgy, whose unstinting efforts to keep Bess away from cocaine and her no-good boyfriend Crown are nothing short of heroic.

Booming bass-baritone Eric Owens as Porgy started out a bit stiffly, but his voice freed up after the optimistic banjo ditty “Oh, I got plenty o’ nuttin”. For the love duet, “Bess, you is my woman now”, Owens was in resplendent voice, matched by the full, penetrating soprano of Adina Aaron as Bess. In the final scene, when Porgy discovers that Bess has left for New York with her drug dealer, Owens was heart-rending, releasing a flood of raw emotion that left him visibly drained at the curtain call. Besides singing formidably, Aaron encompassed all aspects of the tragic Bess–her physical attractiveness, kindness and ongoing struggle against her weaknesses. Bass-baritone Mark S. Doss was to sing the violent Crown, but had to cancel due to illness. Luckily, DNO was able to fly in Nmon Ford from the States to replace him. Ford, who had sung the role in London, was wholly persuasive as the brutish drunk who kicks off the plot by killing a man over a game of dice. When, on the run from the law, Crown seduces Bess away from Porgy, he was sexy and dangerous. He and Aaron made the stage sizzle. Perhaps fighting jetlag, he seemed to tire towards the end and did not have enough volume to project the racy “A red-headed woman”.

Tenor Frederick Ballentine was a class act as the slippery cocaine dealer Sportin’ Life. He turned the irreverent sermon “It ain’t necessarily so” into a spectacle of vocal suppleness and style. Another star turn was Latonia Moore’s golden-voiced Serena, harrowing as the keening widow in “My man’s gone now” and powerful when leading the faith healing session for the ailing Bess. Donovan Singletary and Janai Brugger were an engaging Jake and Clara, her soprano clear as a bell in the lullaby “Summertime”. The powerhouse Maria of mezzo-soprano Tichina Vaughn put Sportin’ Life in his place with a flawlessly inflected “I hates yo’ struttin’ style”. The singing got even better in the ensembles, above all in the rousing spiritual harmonies. The especially assembled chorus, more a set of soloists really, also took the smaller roles. They were all taken beyond reproach, with outstanding performances by tenor Ronald Samm as Peter the honey seller and sopranos Sarah-Jane Lewis and Pumza Mxinwa as, respectively, Annie and Lily. As a chorus they were galvanizing, deeply moving as mourners at the wake, infectious in foot-tapping numbers such as “Oh, I can’t sit down”. As for the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra under the expert baton of James Gaffigan–they got rhythm. Gaffigan approached the score respectfully while delighting in its exhilarating mix of jazz, Jewish religious melodies and spirituals. All sections of the orchestra were firing on all cylinders from the first bar, but special honors go to the killer xylophone.