November 30, 2019

Saint Cecilia: The Sixteen at Kings Place

But, no matter. This performance by Harry Christophers’ ensemble at Kings Place was characteristically accomplished and well-composed, in terms of, respectively, the singers’ assurance (though I’m not sure why Christophers needed to employ pitch pipes between items, given the singers’ experience and the harmonic clarity and focus of the works performed) and the balance of compositional styles presented.

Britten’s ‘A Hymn to the Virgin’ (1931) opened proceedings, and here the strengths of The Sixteen were obvious: the clarity of diction; the persuasive nuance of suspension and dissonance; the give and take between phrases which creates fluency; the independence of voices where necessary which injects drama and vigour.

The programme included works by many women composers of the 20th and 21st centuries. Ruth Byrchmore’s ‘Prayer of St Teresa of Avila’ was noteworthy for the way harmonic stasis and movement were opposed, creating a dynamism that flowered in rich timbral majesty. In contrast, the lines of the composer’s ‘A Birthday (St Cecilia)’ seemed at times to be swimming against each other, resulting in no less dynamic urgency. The latter climaxed in a sustained proclamation, “my love is come to me”, through which the female voices seemed to evolve from a human to an instrumental to an almost abstract timbre.

We had two works by Cecilia McDowall, ‘Now may we singen’ and ‘Of a Rose’, both of which recalled carolling traditions - and the spirit of John Rutter - in their combinations of melody and drone, and the temporal flexibility which seems to be a direct representation of linguistic veracity. Similarly, there were two works by Margaret Rizza: ‘O speculum columbe’, which sprayed its harmonic light like a fan of colour in the opening stanza, and ‘Ave generosa’ which was one of the evening’s more individual and engaging offerings, bringing together soprano and alto solos in a complementary partnership and culminating in a blaze of jubilation: “Dei Genitricem. Amen.” (Mother of God. Amen)

The programme did evince an occasional waft of ‘English gentility’: Elizabeth Poston’s ‘Jesus Christ the apple tree’ was an exquisite dose of Christmas-come-early; The Sixteen’s Kim Porter showed her choral nous in ‘Christmas Eve’, combining contrapuntal dialogue with harmonic nuance. But any sense of comfort or complacency, however beautiful, was challenged most creatively by Alissa Firsova’s ‘Stabat Mater’, which foraged through piquant harmonic landscapes and sonorities, exploiting false relation and flattened ‘blue notes’, and sculpting an architectural expanse of quiet dignity. Similarly Peter Maxwell Davies’ ‘Lullaby for Lucy’ made its mark without undue ceremony: as the text spoke of “plants and creatures of the valley” which “Unite,/ calling a new/ Young one to join the celebration”, so the music expanded organically from tenor solo to tender intertwinings, culminating in startling luminosity: “Lucy came among them, all brightness and light.”

Ironically, if there was one item that left me feeling a bit ‘bristly’ it was Britten’s Hymn to Saint Cecilia. Though the text was well articulated throughout, I longed for more rhythmic swing and suaveness at the opening, to avoid the impression of English-country-house etiquette and stiff-upper-lips. In the second section, “I cannot grow”, there was precision but not tension: the counterpoint was precise but prim. The tuning of some of the unison refrains was not entirely settled, though there was a persuasive organ-like timbre and sonority at time for the appeal, “Blessed Cecilia, appear in vision”; the pause on “Love me” at the close of this second section was distinctly troubled intonation-wise.

With the arrival of the concluding Auden poem, “O ear whose creatures cannot wish to fall”, I longed for more fluency of line: all was absolutely accurate, but, for example, the men’s stepwise lines came across as separate notes rather than a melodic sweep. And, this may be an entirely personal preference or predilection, but I found soprano solo - though powerfully sung by Julie Cooper - too empowered and vibrant: this is surely an angelic song, and if we can’t have a boy soprano then we might have a voice which approximates the abstract elevation of such? Similarly, when it came to the poetic ‘punchline’, so to speak, I felt that Jeremy Budd’s solo tenor proclamation, “O wear your tribulation like a rose”, needed greater spaciousness to take in the import of the text; and that more precise tuning of the chord supporting the fanfare-like declaration was required. This work highlighted, too, the tendency of The Sixteen to over-sing in this venue; they did not need to cast their utterances into a cathedral’s sonic void that would magnify and return and enrich; the acoustic in Hall One is excellent, the space fairly intimate. Less would have been more at times.

Most affecting of all was Herbert Howells’ ‘Take him, earth, for cherishing’, which is often said to have been commissioned following the death of John F. Kennedy, though the real dedicatee is surely Howells’ son, Michael, who died 28 years earlier from polio. The initial unison challenged; imperatives, “Guard him well”, compelled; the counterpoint was simultaneously knotty and dynamic: “Comes the hour God hath appointed/ To fulfil the hope of men:” The plea to the Lord, “O take him, mighty Leader, Take again thy servant’s soul”, was expansive and compelling. The final prayer, “Take him, earth, for cherishing.”, was quietly touching. Christophers sculpted a cathedral of sound, simultaneously gracious and fragile.

Claire Seymour

The Sixteen:

Saint Cecilia

Harry Christophers (conductor)

Britten - Hymn to the Virgin, Ruth Byrchmore - Prayer of St Theresa of Avila, Britten - Hymn to Saint Cecilia, Cecilia McDowall - Now May We Singen, Margaret Rizza - O Speculum Columbe, Alissa Firsova - Stabat Mater, Howells - Take Him Earth for Cherishing, Kim Porter - Christmas Eve, Byrchmore - A Birthday (St Cecilia), McDowall - Of a Rose, Roxanna Panufnik - Prayer, Elizabeth Poston - Jesus Christ the Apple Tree, Maxwell Davies - Lullaby for Lucy, Rizza - Ave generosa.

Kings Place, London; Friday 29th November 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/The%20Sixteen.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=The Sixteen at Kings Place: Saint Cecilia product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: The Sixteen

November 29, 2019

Liszt Petrarca Sonnets complete – Andrè Schuen, Daniel Heide

Since no complete edition of the Liszt songs exists apart from the Alexander edition for Breitkopf and Härtel in 1919-21, this may be more than an ordinary completist series. There could be as many as 145 variants, with questions of classification, since Liszt did not not assign opus numbers. This recording seeks to highlight the connections between Liszt’s three settings of Petrarch’s Sonnets 47, 104 and 123. Recorded in the Marküs -Sittikus Saal in Hohenems, these are performances of great sensitivity, as we’d expect from Schuen, and Heide.

Andrè Schuen is easily one of the more promising young baritones around, and one whose genuine love for repertoire leads him to in-depth performances of more eclectic material. He recorded an outstanding Frank Martin Sechs Monologe aus Jedermann as well as Schumann, Beethoven and Wanderer, an excellent collection of Schubert Lieder. At the Wigmore Hall on Saturday 23rd November, Schuen and Heide are giving a recital of Schubert and Mahler (Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen and the Rückert Lieder).

Liszt’s first settings of the Petrarch sonnets date from 1842-6 while the second settings were completed between 1864-1882. Composed decades apart, these are far more than simple “variations” but thoroughly thought-through new works, showing the evolution of Liszt’s approach though time. The order of songs is also transposed. In the first Sonetto 104, (Pace non trovo) is declamatory, each verse clearly separated by a piano interlude. The line “equalamente mi spiace morte et vita” rises with operatic flourish, before a hushed ending, marked by two assertive chords on the piano for emphasis. The second Sonetto 104, better reflects the brief phrases in the poem, which flow in succession, building up tension towards the line “né mi vuol vivo, né mi trae impaccio” expressing the poet’s frustration. The line “in questa stato son, donna, por voi” is all the more moving because it expresses love, tenderly complemented by a gentle piano postlude.

In the first Sonetto 47 (Benedetto sia ‘l giorno), the mood is gentler, suggesting the purity of the beloved. Elaboration is focused on the third strophe “Benedette le voci tante” where phrases are repeated, adding lustre to the name “Laura”, which Schuen projects with glowing awe. The second setting of this sonetto is even more sensitive, Liszt’s attention even better attuned to the scansion of Petrarch’s flowing phrases, “‘l giorno, e ‘l mese, e l’anno, e la stagione, e ‘l tempo, e l’ora, e ‘l punto”, which are all connected, since they underline the meaning of the poem. Schuen’s perfect diction underlines the melodious nature of the text. Only in the line “E le piaghe, ch’infino al cor mi vanno” is there a hint of the pain the poet is going through. With such subtlety, Liszt has no need to decorate the third strophe: its impact comes from the sincere, direct expression of emotion. This makes the final strophe even more moving, as it gradually decelarates into quietude. For the poet, nothing matters but the beloved: “Ch’ è sol di lei” sings Schuen with deep feeling, “si ch’altra non v’ha parte”. As the song subsides, the word “benedette” is intoned, like a prayer.

An extended piano prelude introduces the first setting of Sonetto 123 (I’ vidi in terra), the genly rocking melody taken up in the vocal line. The beloved is now a memory, “par sogni, ombre e fume”. Though there are differences in the two settings for voice and piano, the focus is now on the poet, alone. For Liszt as composer, such personal expression would have favoured the piano. Given that the versions for solo piano from Années de Pélerinage, Année II (Italie) S 161 no. 4 to 6 were written shortly after the first settings of the songs for voice and piano, S 270a, it is natural that the resemblances are strong. The popularity of the pieces for piano thus derives from the emotional power inherent in the songs, even shorn of text. Hearing all three sets together enhances understanding of their context and the role they play in the development of Liszt’s oeuvre. Paradoxically, this also means a greater appreciation of the later set, known as S 270b, but much more mature, subtle and sophisticated than mere variation.

Appositely, Schuen and Heide conclude this first volume in the Liszt Lieder series with Liszt’s setting of Victor Hugo, Oh! Quand je dors, S 282, here in the second version, completed in 1859. Many of Liszt’s songs are standard repertoire, but the time has come for a re-evaluation of all the songs, in context. Recently, Cyrille Dubois and Tristan Raës presented Liszt Lieder together with his Mélodies in the French style, demonstrating how original Liszt was, a composer “beyond boundaries”, so to speak. Please read more about that here. Essential listening for all.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/8553472.png image_description=Avi-Music 4260085534722 product=yes product_title=Franz Liszt : Petrarca Sonnets product_by=Andrè Schuen, baritone and Daniel Heide , piano. product_id=Avi-Music 4260085534722 [CD] price=$17.21 product_url=https://amzn.to/34z9JmRNovember 26, 2019

Insights on Mahler Lieder, Wigmore Hall, Andrè Schuen

Everyone has heard the Schubert favourites Schuen and Heide chose, maybe hundreds of times, but Schuen and Heide made them feel fresh and personal. An den Mond D259, illuminated with subtle restraint, Im Frühling D882, full-throated and free-spirited, Abendstern D806, gently contemplative. Schuen and Heide know how to programme, varying songs of introspection with exuberant outbursts like Der Musensohn D764. The second half of the recital was even better: a particularly tender Sei mie gegrüsst D741 and Dass sie hier gewesen D775. Together they demonstrated Schuen’s range, which effortlessly reaches the upper limits of baritone, to near-tenor brightness. He’s still young but has huge potential – definitely a singer to follow.

Schuen and Heide have often explored less familiar parts of the repertoire, like their outstanding Frank Martin Sechs monologe aus Jedermann so it was interesting to hear how they’d do Mahler Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, which just about everyone has done, not always to best effect. This is very much a young man’s adventure, as it was for Mahler himself, setting out on his own journey. Despite a slightly cautious start, understandable enough, Schuen soon got into his stride. Schuen’s diction is agile, an energetic, even stride in his phrasing. The poet sets out, upset because he’s been rejected by a girl, but his love may have been little more than teenage fantasy. Almost immediately he is drawn to Nature and the world beyond himself. “Ziküth, Ziküth” here rang strong and pure, as if modelled on hearing bird song ringing in the wild, for the bird symbolizes destiny – Siegfried, heading off down the Rhine, led by a wood dove in the forest. Thus revitalised, the poet looks ahead. Schuen breathed into the phrase “Blümlein blau! Verdorre nicht!” making the words glow with wonder. Anyone who’s seen gentians in Alpine regions, growing out between rocks, know exactly why they can feel miraculous. No surprise then that Schuen and Heide gave the second song “Ging heut’ Morgen über’s Feld” such heartfelt vigour. Flowing, decorative phrasing in “Wird’s nicht eine schöne Welt?Zink! Zink! Schön und flink! Wie mir doch der Welt gefällt!” Sparkling piano figures lead into a new, more serene mood, where lines stretch smoothly, held for several measures, as if basking in Sonnenschein.

With “Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer” the mood shifts, like sudden storm, descending on a mountain. The dark resonance in Schuen’s lower register highlighted the drama. But yet again, Mahler doesn’t dwell on angst: the drama here is almost as if the poet were reminding himself to be angry – as teenagers do – when he has in fact moved on. In the final song, Schuen showed the lyricism and tenderness in his timbre, which in many ways is even more impressive than the volume he can achieve when needed. The Lindenbaum reputedly has narcotic qualities, that can intoxicate those inhaling the scent of its leaves and flowers. Perhaps the poet might die (as suggested in Winterreise) but for Mahler, the song is lullaby. Sleep can refresh and re-invigorate. Schuen’s style is direct, with clear-eyed focus, totally appropriate to this cycle.

Mahler’s Rückert-Lieder are not a cycle, as such, and the sequence can be altered. Schuen and Heide put the more overt songs of love together forming a miniature cycle of their own, followed by Um Mitternacht, in which the poet confronts mortality, and Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen, in which the poet comes away from the cares of the world. The Rückert-Lieder are in an altogether more sophisticated league than Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, but Schuen and Heide rose to the challenge. Their performance here was the highlight of the whole evening. Lovely as these songs are, loveliness alone means little. What impressed me most was the emotional maturity and artistic insight Schuen and Heide brought to this interpretation, which can elude some bigger-name celebrities.

A particularly beautiful Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft. Again, a Lindenbaum, whose scent is powerful, but invisible. Subtlety is of the essence: Schuen and Heide seemed to make the music hover, shaping lines without forcing them, Schuen breathing carefully into each phrase, using air itself, like an Äolsharfe. Vowel sounds surged, consonants softened. It is significant that Rückert’s poem is almost minimalist, images suggested with as few words as possible. Similar gentleness in Liebst du um Schönheit. Rückert’s lines are again deceptively simple, almost childlike. Schuen understands that less is more, allowing the song to reveal its purity as it unfolds.

Um Mitternacht thus operates as contrast, not only in purely musical terms, but also to emphasize meaning. If the poet dies, his dilemma is even more poignant if he had had a good life. While the other songs are near lullaby, Um Mitternacht is an anthem, ringing out with impassioned dignity, connecting the individual to the cosmos. “Um Mitternacht hab ‘ ich gedacht Hinaus in dunkle Schranken.” All that separates life from death is the beating of the heart, “ein einz’ger Puls”. An image of fragile humanity, reminding us that all the powers of this world can come suddenly to nothing. As so often in Mahler, bombast is inappropriate. Instead, humility and respect for something greater than the individual. “Herr über Tod und Leben Du hältst die Wacht Um Mitternacht!”. Heide’s lines are firm and steady: Schuen’s voice rings with dignity and affirmation. Thus the logic of concluding with Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen : after the storm, the calm of true wisdom. The protagonist isn’t actually dead but has learned that wasting time on pettiness is futile. “Ich bin gestorben dem Weltgetümmel..... ich leb’ allein in meinem Himmel, in meinem Lieben, in meinen Lied”. This was an excellent performance, but in time, Schuen will develop and find even more in this group of songs.

Thus, the logic behind the choice of encore, Urlicht, Mahler’s setting of Nietszche, which he incorporated into his Symphony no 2, heard here in the version for voice and piano. In the symphony it serves as a transition between the “worldy cares” evoked in the quotation of Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt in the previous movement and the resolution, the “resurrection” in the finale. “O Röschen rot!”, an image of beauty that must, inevitably fade, Schuen’s voice warming the “o” sounds, so they felt sensual, which occur again in the next phrase, but with a chill. But this nadir of suffering is but a phase. Even angels cannot divert the supplicant from his/her goal. “Ich bin von Gott und will wieder zu Gott!” Schuen sang with resolve, suggesting great inner strength. God will light the way to “das ewig selig Leben!”.

Franz Liszt’s S290, Morgens steh’ ich auf und frage, a setting of Heinrich Heine, provided the second encore. Again, a deceptively simple text, suggesting more than mere words, Liszt’s setting more pianistic than Schumann’s. Schuen and Heide are planning a complete series of Liszt Lieder, the first volume of which features all three versions of the Tre Sonnetti de Petrarca (Petrarca Sonnets). Please read my review of that HERE.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Andre_Schuen_1_cGWerner_v.jpg image_description=Andrè Schuen [Photo © Guido Werner] product=yes product_title=Mahler and Schubert Lieder. Andrè Schuen (baritone), Daniel Heide (piano) Wigmore Hall, London, 23rd November 2019. product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio product_id=Above: Andrè Schuen [Photo © Guido Werner]Ermelinda by San Francisco's Ars Minerva

Sig. Freschi’s little divertimento was a but a small part of a much bigger evening that went on, I assume, to include at least a naval battle on the villa’s pools, grandiose entertainment for a multitude of invited dignitaries.

A larger perspective of Venetian opera finds Monteverdi’s complex Coronation of Poppea premiere in 1643. Francesco Cavalli’s racy, slice-of-debauched-aristocratic-life operas that we see these days come from the 1650’s (his famed Parisian misadventure with theatrical machinery, Ercole Amante, was in 1662). Antonio Vivaldi, the resident musician of a Venetian orphanage for musically talented girls, came onto the local opera scene as an impresario of the newer Neopolitan style in 1712, and later (1727) wrote his own Orlando furioso based on Ludovico Ariosto’s 1513 epic poem that had established a psychopathology of love that more or less endured until the Romantics.

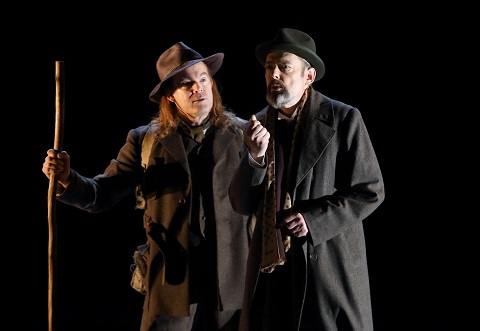

Sara Couden as Clorindo, Kindra Scharich as Rosaura

Sara Couden as Clorindo, Kindra Scharich as Rosaura

All these threads converge in Sig. Freschi’s little comedy for the Doge’s son Marco whose country estate included an orphanage for talented girls. Possibly this orphanage resource is why the Ars Minerva production made use of only treble voices — one male lover was a trouser soprano, the other was a trouser contralto. Ermelinda and her friend Rosaura were duly female. Ermelinda’s father was a male mezzo-soprano (countertenor).

In short, Ormondo loves Ermelinda, Armidoro does too. Ermelinda loves Ormondo, Rosaura does too. Ormondo becomes the mad Clorindo who pretends to love crazy-in-love Rosaura. Aristeo, Ermelinda’s father, intervenes. Ermelinda tries to kill herself for love. Unlike a Cavalli plot this one is quite simple, and unlike Cavalli’s variety of musical forms Sig. Freschi limits himself to recitative, arioso and through composed arietta. There were a few ritornellos and only one sort of duet in the string of solo numbers that told the story very simply and very directly. The dignity of early Venetian opera had long since been thrown into the canals and the grandiose, embellished arias of the Baroque are many years away,

There was no need for theatrical machinery. We were either indoors or out. The Ars Minerva production covered the huge back wall of the 171 seat ODC Theater (a fine dance venue in San Francisco’s Mission district) with projected images created by Entropy (a person’s name) that colorfully abstracted architectural detail vaguely reminiscent of the period.

The elaborate costumes, wittily abstracted from period shapes were designed by Matthew Nash, now retired from the San Francisco Opera costume shop. Stage director Céline Ricci deftly moved her actors around simple, portable props in the center of the expansive dance floor, the Ormondo gone mad — as Clorindo — teased theorbo player Adam Cockerham who was seated with the harpsichord, cello, and three da braccio viols far stage left.

The program booklet does not credit an edition of Sig. Freschi’s little opera, thus we may assume that early music harpsichordist and conductor Jory Vinikour organized the production musically based on a manuscript found at Venice’s Marciana Library. It is lively music that flows in very natural speech rhythms enhanced with very inventive melodic riffs that tease and amuse us and become upon occasion quite specific songs. These players were a confident lot that gave us great delight in their ritornellos. The three instrument continuo cleverly supported the excellent performances center stage.

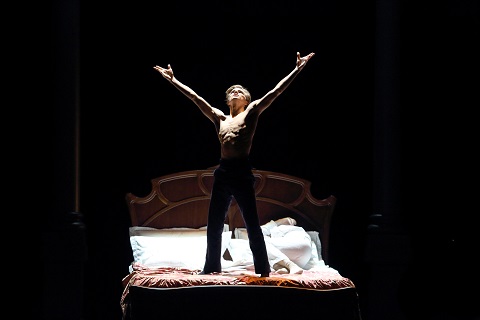

Nikola Printz as Ermelinda, lighting design by Thomas Bowersox

Nikola Printz as Ermelinda, lighting design by Thomas Bowersox

Those 17th century dignitaries will have been mightily amused as we were with the broad comic antics of a nicely matched cast. Ermelinda was sung by mezzo-soprano Nikola Printz who brought rich tone and informed period inflection to her femme fatale role, and created, with Sig. Freschi’s help, convincing musical pathos in her attempted suicide. Her friend and rival Rosaura was sung by Kindra Scharich who made this love sick character a comic masterpiece, every sung phrase an insidious calculation, every movement a neurotic gesture, and all in beautiful voice that flowed naturally over composer Freschi’s finely chiseled lines.

Contralto Sara Couden sang Ermelinda’s suitor Ormondo who disguised himself as a peasant named Clorindo to fit into pastoral life. Mlle. Couden possesses a rare contralto voice that offers her a wide range of roles — from this vocally convincing castrato role, to the nurses, grandmothers and witches of later repertory. She gave herself to the creation a truly rustic Clorindo who goes out and in of feigning madness. Clorindo’s rival for the love of Ermelinda, soundly thwarted, is Armidoro sung by soprano Deborah Rosengaus who created one of the most beautiful musical moments of the evening in her final lament, singing composer Freschi’s fine music with exquisite phrasing.

And what would an Italian opera of this period be without a countertenor! Thus male mezzo soprano Justin Montigne sang Ermelinda’s father Aristeo! Not exactly gender bending, but possibly representative of the musical norms of a time gone-by where voices interacted and competed musically rather than theatrically.

Ars Minera is in its fifth year of presenting the modern world premieres of forgotten operas (one opera each year)!

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Ermelinda: Nikola Printz; Ormondo/Clorindo: Sara Couden; Rosaura: Kindra Scharich; Aristeo: Justin Montigne; Armidoro: Deborah Rosengaus. Conductor/Harpsichord: Jory Vinikour. Stage Director: Céline Ricci; Projections: Entropy; Costume Designer: Matthew Nash; Lighting Designer: Thomas Bowersox. ODC Theater, San Francisco, November 23, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ermelinda_SF1.png

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Ermelinda by San Francisco’s Ars Minerva

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Kindra Scharich as Rosaura

Photos by Teresa Tam courtesy of Ars Minerva

Wozzeck in Munich

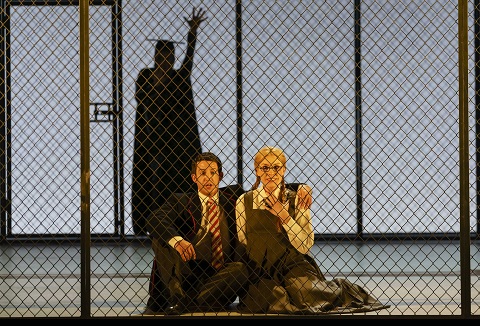

At its heart, in every sense, lay Christian Gerhaher’s Wozzeck, Gun-Brit Barkmin’s Marie, and their child, touchingly sung by Alban Mondon.

Christian Gerhaher (Wozzeck)

Christian Gerhaher (Wozzeck)

I have heard some fine Wozzecks over the years; Gerhaher must surely rank alongside the finest. He has been selective in his opera roles; it would, however, be an over-simplification verging on distortion to say that he is more at home in the concert hall. Wozzeck is, of course, a very different role from his fabled Tannhäuser Wolfram and is surely the sterner dramatic test, perhaps especially for someone with so heartbreakingly beautiful a voice. Or so it might seem on first glance, but Gerhaher is an artist at least as celebrated for intelligence and humanity. His way with words, music, and gesture too simply had one believe that this was the character he was playing. Verbal nuance without pedantry, attention to musical line without a hint of self-regard, harrowing facial expression that demanded our sympathy: yes, this was a compleat Wozzeck. Barkmin’s Marie, equally well sung (and spoken), equally sympathetic, made for a fine complement indeed. Through her artistry one felt her hopes as well as her devastation, her pride as well as her capacity for love. Wolfgang Ablinger-Speerhacke’s Captain, John Daszak’s Drum Major and Jens Larsen’s Doctor skilfully trod the line between character and caricature, no mean feat in a production that often called upon them to accentuate the grotesque. Kevin Conners as Andres and Heike Grötzinger as Margret impressed too, carving out their own dramatic potentialities, even as we knew them no more likely to succeed than the opera’s central couple. Cast from depth, this was a fine Wozzeck for singing-actors.

Hartmut Haenchen’s conducting proved efficient most of the time, albeit with a few too many discrepancies between sections of the orchestra as well as between orchestra and pit. To be fair, there were also passages—often the interludes—in which all came together to offer something considerably more than that. Haenchen’s reading was not for the most part, however, one to offer any particular revelation. He clearly knew ‘how it went’, yet the post-Wagnerian orchestra as dramatic cauldron had its juices emerge only fitfully.

Gun-Brit Barkmin (Marie) and Ensemble

Gun-Brit Barkmin (Marie) and Ensemble

Andreas Kriegenburg’s production seemed conceptually a little unsure of what it was trying to achieve. Straddling the divide between Expressionist grotesquerie—some arresting images there—and social realism—with a curious twist of Brechtian image, not dramaturgy—is a perfectly reasonable strategy. Communication of how the two might intertwined proved more elusive. Updated to what seemed to be more or less the time of composition, the production left no doubt of the gross injustice and poverty pervading the world in which these events took place. I could have done without all the splashing round in the lake below. Kriegenburg often scored, however, in particular dramatic touches: above all, the acts of Wozzeck’s son, keen to learn from his ill-fated father: watching, listening. and in some cases, acting, as when this evidently wounded child broke his mother’s heart by painting the accusation ‘Huren’ (‘whore’) on her wall. All was lost, then: a moment of devastation. Already we knew what fate, or rather society, had in store not only for Wozzeck and Marie, but for their child too. ‘Wir arme leut’ ...

Mark Berry

Alban Berg: Wozzeck

Wozzeck - Christian Gerhaher, Drum Major - John Daszak, Andres - Kevin Conners, Captain - Wolfgang Ablinger-Speerhacke, Doctor - Jens Larsen, First Apprentice - Peter Lobert, Second Apprentice - Boris Prýgl, Fool - Ulrich Reß, Marie - Gun-Brit Barkmin, Margret - Heike Grötzinger, Marie’s Child - Alban Mondon, Lad - Jochen Schäfer, Soldier - Markus Zeitler; Director - Andreas Kriegenburg, Conductor - Hartmut Haenchen, Set Designs - Harald B Thor, Costumes - Harald B Thor, Costumes - Andrea Schraad, Lighting - Stefan Bolliger, Choreography - Zenta Haerter, Dramaturgy - Miron Hakenbeck, Bavarian State Opera Chorus (chorus director: Stellario Fagone), Bavarian State Orchestra.

Nationaltheater, Munich; Saturday 23rd November 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Barkmin%20Daszak_W._Hoesl.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Berg, Wozzeck - Bavarian State Opera, Munich product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Gun-Brit Barkmin (Marie), John Daszak (Drum Major)Images © W. Hösl

November 25, 2019

Une soirée chez Berlioz – lyrical rarities, on Berlioz’s own guitar

The booklet notes by Bruno Messina, the Berlioz scholar, read like poetry, evoking what an intimate evening with Berlioz himself might have been, in the company of those closest to him, making music for their own pleasure. “Ni festival, ni requiem, ni symphonie, ni opéra, mais une invitation à partager une soirée chez Berlioz et quelques impressions musicales, de celles qui ne font pas beaucoup de bruit mais qui s’inscrivent dans le cœur (comme ces inflexions “des voix chères qui se sont tués”) et qu’on porte longtemps avec soi…”. Though this soirée chez Berlioz is refined and lyrical, and can be enjoyed on its own terms, this recording includes many lesser known works, which enhance our appreciation of the breadth of Berlioz’s art, sensitively and beautifully performed. A must for true Berlioz aficionados.

Indeed, the instruments played here are not only period but unique. The guitar belonged to Berlioz himself, who used it regularly, and to Paganinni before him. The maker was Jean-Nicole Grobert, whom the composer knew well. Given its significance, Berlioz inscribed the guitar with his signature when he donated it to the Conservatoire de Musique. The piano was made by Ignace Pleyel and was used by Chopin and is beautifully preserved. More technical details in the notes.

The evening begins with Plaisir d’amour. It is heard here in the 1784 original for voice and piano by Jean-Paul-Égide Martini. Berlioz liked it so much that he made an arrangement for voice and small orchestra, with flutes, clarinets, horns and strings. As a child, Berlioz enjoyed the tales of the poem’s author, Jean-Pierre Florian. Around 1859, he made an arrangement for voice and small orchestra, but he would undoubtedly have heard and played the original for voice and piano. Williencourt’s technique makes this Pleyel grand from 1842 sound as agile and delicate as a fortepiano. Viens, aurore and Vous qui loin d’une amante are settings of other poems by Florian in troubador style. Roussel’s background in lute and early stringed instruments enhances his way with Berlioz’s period guitar. Viens, aurore is a setting by Lélu (1798–c1822) and Vous qui loin d’une amante a setting by François Devienne (1759–1803).

Berlioz’s La captive is best known in its orchestral version H60 from 1848, but is heard here in Berlioz’s adaptation for voice, piano and violincello (Bruno Philippe) made soon after the first version for voice and piano, from 1832. Seven songs for voice and guitar follow and three for solo guitar, interspersed with settings by Berlioz and Liszt. These are well worth including since this rare opportunity to hear Berlioz’s own guitar should not be missed. The timbre is distinctive, warmer and less strident than guitars made for different repertoire, particularly sympathetic to French style and to the elegance of D’Oustrac’s voice. These relatively unknown works also provide context for Liszt’s L’Idée fixe LW A16b an Andante amoroso “pour le piano d’après une mélodie de Hector Berlioz” making further connections between Berlioz and Liszt. Though Liszt generally preferred an Érard, this Pleyel is still closer to the instruments Berlioz knew so well, and appropriate for the the intimate feel of this “soirée chez Berlioz”.

Also included are Liszt’s transcriptions for piano (LW 205) of Berlioz’s “Danse de Sylphides” from The Damnation of Faust, and “Marche des Pèlerins” (LW A29) from Harold en Italie Berlioz’ Le Jeune Pâtre breton H 65C to a pastoral text by Auguste Brizeux (1803–1858) a poet and man of the theatre who popularized the language and heritage of Brittany. Hence, perhaps, Berlioz’s use of the cor naturel, (Lionel Renoux), evoking the sounds of Breton lovers calling to each other over mountains and valleys, “semble un soupir mêlé d’ennuis et de plaisir”. Berlioz’s Fleuve du Tage (H.5) for voice and guitar is very early Berlioz indeed, written at the age of 16. The Élégie en prose H.47 for voice and guitar sets a translation of a poem by Thomas Moore and comes from Berlioz’s Neuf mélodies irlandaises, op. 2, H. 38.

Anne Ozorio

[Click here for album contents.] image=http://www.operatoday.com/71nMFiiNhAL._SX522_.png image_description=Harmonia Mundi HMM902504 product=yes product_title=Une Soireé Chez Berlioz product_by=Stéphanie D'Oustrac (soprano), Thibaut Roussel (guitar), and Tanguy de Williencourt (piano). product_id=Harmonia Mundi HMM902504 [CD] price= $16.99 product_url=https://amzn.to/2OK2BxpKorngold's Die tote Stadt in Munich

Some of Korngold’s music I have responded to warmly, some less so. (It

would still take some persuasion, though now less than before, to drag me

to another performance of Das Wunder der Heliane.) My experience

with Die tote Stadt has been mixed too. That, however, is bye the

bye, for this new production and still more the performances within it,

superlatively conducted by Kirill Petrenko, made for a splendid evening

that more or less had me forget reservations hitherto entertained.

Petrenko’s conducting and the playing of the Bavarian State Orchestra could

hardly have been bettered. There was no doubting the care taken in his

preparation, nor his ability vividly and meaningfully to communicate

understanding of the score in the theatre. Once the harmony becomes more

interesting, during the second and third scenes, Petrenko showed himself

equally alert to its shorter-term expressive potential and, score

permitting, longer-term tonal implications. There is greater progress in

such terms here than in, say, Schreker’s more harmonically—and

dramaturgically—adventurous Die Gezeichneten, which ends up going

round and round in circles, having one thank God for Schoenberg and

Stravinsky. Petrenko likewise showed skill surpassing that of any conductor

I have heard in communicating Korngold’s motivic working as dramatic past,

present, and future. The orchestra, moreover, offered a far more variegated

sound than I heard from the Vienna Philharmonic in Salzburg in 2005; if

that calorific frenzy impressed in its own way, this was ultimately a more

revealing sound as part of an overall dramatic conception. Where some

performances of what we may broadly call ‘late Romantic’ music—a term I

generally avoid on account of chronological absurdity and levelling

generalisation—all too readily become congested, here was a panoply of

orchestral colour that shifted before our ears so as to suggest, at least

during the most skilfully composed passages, ready understanding of

Straussian phantasmagoria.

Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl.

Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl.

For whereas in Salzburg, Willy Decker’s staging (later seen at Covent

Garden too) was very much in ‘period’ keeping not only with Korngold but

also with George Rodenbach’s Bruges la morte, Fernand Khnopff, et al.—and as such will I suspect greatly have appealed to

enthusiasts—Stone’s production offered a welcome contemporary—to

us—alternative for those who, like me, find the opera’s laboured symbolism

both stifling and a little empty (as well as curiously dated for 1920).

Here, Paul’s house (no.37: no evident symbolism to me, though you may know

otherwise) is the focus for a cancer bereavement—as we learn when we later

behold Marie’s apparition—from which he shows no sign of recovering. One

room’s every wall is covered with pictures of her; he hangs her hair in his

bedroom; some of the house, furniture covered, goes unused; and so on. His

housekeeper, Brigitta, and friend, Frank, are clearly, justifiably

concerned. However, a psychonalytical dream sequence appears to offer the

route to recovery. Having at least begun to work out some of his issues

with Marie/Marietta in a dream in which all manner of strange things can

happen and do—the dead town comes into its own, multiplying Doppelgänger, Pierrot-troupes, accusations thrown as freely as

underwear, etc.—there is perhaps some hope for the future in what uncannily

looks and sounds like the morning of a fresh start. Ralph Myers’s revolving

set permits the house to transform itself, almost as if it were turning

itself inside out, as do the characters, their acts, and their neuroses.

‘It was all a dream’ may or may not be a satisfactory solution; if not,

that remains a problem with the work itself. Stone’s production makes

uncommon, if arguably reductive, sense of a text that can readily seem

somewhat silly.

Marlis Petersen, Corinna Scheurle, Mirjam Mesak, Manuel Günther. Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl.

Marlis Petersen, Corinna Scheurle, Mirjam Mesak, Manuel Günther. Photo credit: Wilfried Hösl.

Vocally, this was unquestionably an evening to savour. Jonas Kaufmann’s

voice is a very different instrument from that of a few years ago. Sounding

more baritonal than ever, Kaufmann had lost nothing, however, of his

ability to float and turn a long line, nor to forge from word and tone that

particular, peculiar alchemy of song. In opera, further alchemy is

required, of course, with the art of gesture; this was as compelling a

stage performance—and I have seen a few—as I have seen from him. Kaufmann’s

Paul remembered, lived in, and came close to final suffocation from times

past, but in its final freshness, shared in the hope suggested, if only

suggested, by Petrenko and Stone alike. Marlis Petersen’s Marietta proved

the perfect foil, a high-spirited heir to Strauss’s Zerbinetta, albeit with

the vocal reserves and finely spun line of something more Wagnerian. Her

acting skills proved just as impressive, as did those of other partners

onstage. Jennifer Johnston’s no-nonsense yet compassionate Brigitta,

Andrzej Filończyk’s sympathetic and beautifully sung Frank, the rest of an

excellent supporting cast, estimable choral forces: all contributed to a

dream performance in every sense. In the intelligence of its accomplishment

of values both musical and theatrical, I suspect this Munich Tote Stadt will set a gold standard to successors.

Mark Berry

Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Die tote Stadt Op.12

Paul - Jonas Kaufmann, Marietta/Marie’s Apparition - Marlis Petersen,

Frank/Fritz -Andrzej Filończyk, Brigitta - Jennifer Johnston, Juliette -

Mirjam Mesak, Lucienne -Corinna Scheurle, Gaston/Victorin - Manuel Günther,

Count Albert - Dean Power; Director - Simon Stone, Conductor - Kirill

Petrenko, Assistant Director - Maria-Magdalena Kwaschik, Set Designs -

Ralph Myers, Costumes - Mel Page, Lighting - Roland Edrich, Dramaturgy -

Lukas Leipfinger, Chorus and Children’s Chorus of the Bavarian State Opera

(chorus director - Stellario Fagone), Bavarian State Orchestra.

Nationaltheater, Munich; Friday 22nd November 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Die_tote_Stadt_c__W._Hoesl.%202jpg%20%281%29.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title= Korngold, Die tote Stadt, Bavarian State Opera product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Ensemble

Photo: Wilfried Hösl

Exceptional song recital from Hurn Court Opera at Salisbury Arts Centre

Established in 2017, Hurn Court Opera was founded to give performance opportunities and showcase emerging young soloists at the start of their professional careers. Achievements so far include critically acclaimed productions of Die Zauberflöte and Acis and Galatea, along with two influential competitions that have produced a wealth of talented singers, some of whom are already making their mark on the operatic stage.

Siân Dicker (soprano) and Michael Lafferty (baritone), both former prize winners of the scheme, devised a tour d’horizon of English song, lieder and operatic excerpts under the banner ‘A Shropshire Lad and a Wiltshire Lass’, the whole accompanied by rising pianist and conductor Ashley Beauchamp. Familiar and seldom-performed songs framed an intriguing cocktail of comic, poignant and whimsical offerings to form a compelling evening that could have found an equally attentive audience in London’s Wigmore Hall.

Both singers, already equipped with considerable experience in opera, oratorio and recital work conveyed admirable poise, intelligent musicianship and flawless techniques. They also possessed an easy rapport with the audience in spoken introductions claiming rapt attention while clearly inhabiting differing musical personalities. This last was most evident in the two Mozart duets where Siân Dicker was a feisty Pamina and Michael Lafferty an earnest Papageno in ‘Bei Männern’ ( Die Zauberflöte). It was handsomely sung, as was ‘Là ci darem la mano’ (Don Giovanni), the latter convincing for the not-so innocent protests of Dicker as Zerlina to Lafferty’s seductive Giovanni.

Michael Lafferty. Photo credit: Sebastian Charlesworth.

Michael Lafferty. Photo credit: Sebastian Charlesworth.

There was no doubt about Dicker’s full throttle engagement, with each song oozing characterful expression, vividly so in Libby Larsen’s witty ‘Pregnant’, Mendelssohn’s ‘Hexenlied’ and Walton’s jazzy ‘Old Sir Faulk’, all dashed off with dramatic flair that bodes well for future operatic projects. She was in her element for Jonathan Dove’s ‘Adelaide’s Wedding’ (The Enchanted Pig) where she managed to combine a haughty grandeur somewhere between Mozart’s Queen of the Night and Hyacinth Bouquet. The song could almost have been written for Dicker. But despite ample tones, gorgeously rich in the middle and fruity at the bottom, I would have liked to have heard something less ‘produced’ for Lisa Lehman’s whimsical ‘There are fairies at the bottom of our garden’.

Where Michael Lafferty began warmly yet somewhat diffidently, his well-upholstered baritone found expressive outlet in songs by Otto Nicolai, Duparc and Schubert. But it was in George Butterworth’s A Shropshire Lad (the most substantial group of songs in the programme) where he found his form. There was melting warmth in ‘Loveliest of trees’, swagger in ‘The lads in their hundreds’ and sepulchral tone for ‘Is my team ploughing?’ Best of all was the wonderfully evocative ‘Sicilienne’ by Giacomo Meyerbeer, sung with demonstrable affection and involvement.

Throughout the evening, accompanist Ashley Beauchamp was a sensitive collaborator with a chameleon-like ability to adapt to the numerous musical styles crowding this generously conceived programme.

David Truslove

Siân Dicker (soprano), Michael Lafferty (baritone), Ashley Beauchamp (piano)

Salisbury Arts Centre; Thursday 21st November 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Si%C3%A2n%20Dicker.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Hurn Court Opera at Salisbury Arts Centre product_by=A review by David Truslove product_id=Above: Siân DickerPhoto: Sebastian Charlesworth

Lohengrin in Munich

It was also—and perhaps more surprisingly to me—exceptional in that fine

musical performances rescued the evening from one of the silliest and most

bizarrely irrelevant productions of the work I have ever seen. (For what it

is worth, staging Lohengrin is an issue to which I have given a

good deal of attention; it is, for instance, the subject of a chapter in

one of my books,

After Wagner

.) Increasingly, I have felt that opera performances working only as

music—shorthand, I know—and not as theatre have little interest for me any

more; I may as well stay at home and listen to a recording or read the

score. This, however, was exceptional in that orchestra, singers, and

conductor managed to convince me that I had experienced a dramatic

performance of Lohengrin, acting included, that had little or

nothing to do with what Richard Jones had served up.

Karita Mattila (Ortrud), Anja Harteros (Elsa von Brabant).

Karita Mattila (Ortrud), Anja Harteros (Elsa von Brabant).

Jones presented a banal tale, if one may call it that, of a middle-aged,

middle-class heterosexual couple—a neglected group of whose experience we

all should hear more—marrying somewhere provincial and building a new house

there. That seemed to be it, save for when the house project did not work

out as planned and the house was no longer present. There was occasionally

promise of something else: brown-shirted uniforms suggested something

obvious at the start, yet disappeared in favour of an eccentric

combination—at least in any circles I know—of Tracht and

tracksuits. (Maybe savings needed to be made to finance the crane that

hoisted the roof onto the house.) For some reason, a difficult-to-read

floral inscription in the front garden imitated that on the front of

Wagner’s Wahnfried villa. Doubtless one could propose all manner of

symbolic explanations concerning what various things might have meant; one

would have to, really, since the production appeared not to bother. I am

sure we are all, ‘in a very real sense’, as an Anglican bishop might have

it, building a house, and so on and so forth, but really. King Henry the

Fowler appeared to be a marriage celebrant, not unreasonably confused by

proceedings around him; quite who most of the others were eluded me. Swords

sat awkwardly with the narrative, to put it mildly, yet at least reminded

us that Wagner’s opera has a more involving story to tell. All was blocked

well: credit where credit is due to the Abendspielleitung

(Georgine Balk) and, presumably, to the original production. I cannot

imagine otherwise what else, if anything, ran through Jones’s head. O for a

Hans Neuenfels, a Peter Konwitschny, a Stefan Herheim…

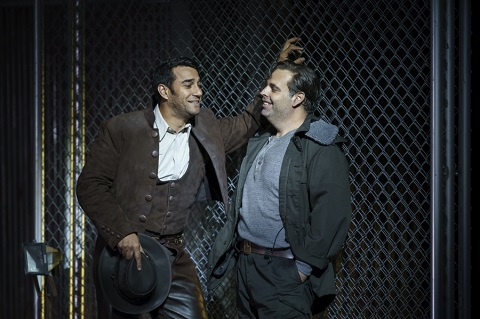

Lohengrin ‘itself’ fared much better. Anja Harteros took a while to warm up, her first act Elsa veering in and out of focus, verbally as well as musically. Once focus had been achieved however, hers was a battle royal with rival Schillerian queen—and sometime Elsa—Karita Mattila. To see and hear the two was to experience something akin to a duet between finest woodwind principals, timbres contrasting yet complementary, albeit with finely honed words and gesture too. The greatest Ortruds command attention even during the first act, the character onstage yet having little to sing. Waltraud Meier did the first time I saw her on stage; so here did Mattila, her interpretative and communicative zeal amply compensating for the vacuity of Jones’s production. Klaus Florian Vogt’s Lohengrin did not settle immediately and is famously not to all tastes. For me, it works considerably better than his other Wagner roles, a sense of unearthly ‘purity’ not at all inappropriate; like his Elsa and Ortrud, he offered a consummately professional performance throughout. So too did Wolfgang Koch as Telramund. An estimable, always likeable artist, he sometimes seemed slightly out of sorts, but there was no doubting the intelligence of his properly Wagnerian blend of word and tone; likewise Christof Fischesser’s King Henry. Gantner’s excellent Herald fully lived up to expectations, as did the Tölz trebles acting as pages and their Brabantian noble colleagues.

Klaus Florian Vogt (Lohengrin), Anja Harteros (Elsa von Brabant).

Klaus Florian Vogt (Lohengrin), Anja Harteros (Elsa von Brabant).

If the orchestra was not always quite on peak form, the first act Prelude a

little bumpy at times, one would have had to be wishing to find fault to be

disappointed. Its strings sounded golden, more Vienna or Dresden than, say,

Berlin, though there were naturally darker passages too, not least during

the Prelude to the second act. Characterful woodwind and a brass section

capable of sometimes breathtaking tonal variegation offered further

orchestral pleasure and insight. Lothar Koenigs’s direction of the whole

was sane, sensitive, and unassumingly purposeful. It certainly never drew

attention to itself, which, after

a certain conductor at Bayreuth this summer

was more than welcome, but instead gave the impression of ‘natural’

communication of Wagner’s melos. There were a few cases of

surprising disjuncture between pit and chorus, but they were rectified soon

enough and did little to spoil one’s enjoyment of some fine choral singing.

All in all, then, an interesting evening—if not quite in the way one might

have expected.

Mark Berry

Richard Wagner: Lohengrin

King Henry the Fowler - Christof Fischesser, Lohengrin - Klaus Florian

Vogt, Elsa - Anja Harteros, Friedrich von Telramund - Wolfgang Koch, Ortrud

- Karita Mattila, King’s Herald - Martin Gantner, Four Brabantian Nobles -

Caspar Singh/ George Virban/ Oğulcan Yilmaz/ Markus Suihkonen, Four Pages -

Members of the Tölz Boys’ Choir, Gottfried - Lukas Engstler; Director -

Richard Jones, Conductor - Lothar Koenigs, Designs - Ultz, Lighting - Mimi

Jordan Sherin, Video - Silke Holzach, Choreographical Assistance - Lucy

Burge, Chorus and Extra Chorus of the Bavarian State Opera (chorus

director: Stellario Fagone), Bavarian State Orchestra.

Nationaltheater, Munich; Thursday 21st November 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lohengrin%20Munich%20title.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Lohengrin, Bavarian State Opera product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Ensemble, Bavarian State OperaPhotographs courtesy of Bavarian State Opera

November 22, 2019

Hansel and Gretel in San Francisco

The grand foyer of the San Francisco opera house was already decked out in green boughs and red bows though Thanksgiving has yet to come. It’s the time of year when some adults think about exposing their children to high art, albeit art that is perceived to be accessible to their innocent psyches. And opera and ballet companies want to take this urge to the bank.

This production by British designer Anthony McDonald, a veteran of several British Nutcracker productions, does wish to tug a bit at your heartstrings more than frighten your children. During the overture you learn that a poor family living in a quite lush and scenic Alpine meadow has insufficient food on its dinner table.

But the two resourceful children in search of strawberries conjure a quite wonderful adventure for themselves in an enchanted forest of golden hued trees filled with fanciful spirits. It was fun to identify these witty additions to the story — I saw Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood and Rapunzel, but there were more.

A lively wood sprite ballerina opened hidden doors on the ornate frame that was a false proscenium to bring on a charming hook nosed, miniature soprano sandman to sedate the children and later a lovely, white dew fairy to awaken them. Atop the ornate frame was an elaborate cuckoo clock that revolved backwards during the overture taking us back to another time, and of course later participating in the children’s musical games.

The Gingerbread House

The Gingerbread House

Though the gingerbread house did not look very tasty (an all brown Victorian cottage with a great big illuminated cherry on its top), it revolved to expose a huge marmite that broke open to reveal a boiled and charred witch, the only macabre moment of the evening and it seemed out of place. For the record the witch was first female, then male thus avoiding a stereotypical witch branding.

There was gorgeous horn playing to begin the evening (and in fact throughout the evening), conductor Christopher Franklin evoking very bright playing from his orchestra that made the performance far more folksongish than Wagnerian. All the familiar pieces of the opera were in great relief, though the beautiful little prayer was uncomfortably soft and somehow the chorus of reanimated children at the end lacked meaning, possibly because we never really felt that Hansel and Gretel were threatened to begin with.

The wanted charm of the evening did not overcome the prevailing atmosphere of boredom I felt. And if I was bored I assume that all those targeted families will be a bit bored as well. For the record the audience was not families (I did saw three or four children) but the usual San Francisco opera audience who are now offered but eight annual operas. This could be a sufficiently satisfying number if all eight were of sufficient weight.

Hansel and Gretel with the Witch

Hansel and Gretel with the Witch

Hansel was mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke of beautiful voice and strong tone, Gretel was soprano Heidi Stober who brought infectious energy and fine singing to her role. Mlles. Cooke and Stober are regulars at San Francisco, as is Michaela Martens who was effective as the mother. Alfred Walker, a bass-baritone from New York, provided a beautifully sung father while underlining the ethnic diversity we take for granted in opera. Tenor Robert Brubaker brought charm rather than menace to the Humperdinck witch. Adler Fellows Ashley Dixon and Natalie Image were, respectively, the Sandman and Dew Fairy. Ballerina Chiharu Shibata offered lovely sous-sus and graceful pas de chat to the Woodsprite.

Hansel and Gretel was sung in an English language translation by David Pountney.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Hansel: Sasha Cooke; Gretel: Heidi Stober; The Witch: Robert Brubaker; Gertrude: Michaela Martens; Peter: Alfred Walker; Sandman: Ashley Dixon; Dew Fairy: Natalie Image; Will-o'-the-wisp: Chiharu Shibata. Childrens Chorus and Orchestra of the San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Christopher Franklin; Stage Director & Production Designer: Antony McDonald; Associate Stage Director: Danielle Urbas; Associate Designer: Ricardo Pardo; Lighting Designer: Lucy Carter; Revival Lighting Designer: Neill Brinkworth; Choreographer Lucy Burge. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, November 21, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/HAnselGretel_SFO1.png

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Hansel and Gretel at San Francisco Opera

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Heidi Stober as Gretel, Sasha Cooke as Hansel

Photos by Cory Weaver courtesy of the San Francisco Opera.

An hypnotic Death in Venice at the Royal Opera House

Aschenbach’s gesture, in the opening scene of David McVicar’s astonishingly hypnotic production of Benjamin Britten’s final opera, anticipates a symbol which does not appear until the latter scenes of Mann’s text, when, following the vulgar musical performance of a group of ‘beggar virtuosi’ in the front garden of the Hotel des Bains, he steals a glance at the young Polish boy Tadzio and reflects, in what Mann describes as ‘that sober objectivity into which the drunken ecstasy of desire somethings strangely escapes’: ‘He’s sickly, he’ll probably not live long.’ Into Aschenbach’s mind intrudes a memory of his parents’ house, many years ago: ‘he suddenly saw that fragile symbolic little instrument as clearly as if it were standing before him. Silently, subtly, the rust-red sand trickled through the narrow glass aperture, dwindling away out of the upper vessel, in which a whirly vortex had formed.’ [1]

Thus, with subtle symbolic foreshadowing, McVicar begins to tell Mann’s and Britten’s tale. Like the rust-red hair shared by the sinister figures who cross Aschenbach’s path in the action which unfolds, the vanishing sand is ominous. “My mind beats on and no words come,” sings Aschenbach. Time is running out: “No sleep restores me.” Repeated references to the passing hours infiltrate Mann’s text and in McVicar’s production the defiant clock makes its presence felt, nowhere more so than when an outsize pendulous clock-face descends and hangs in suspended motion above the gondola in which Aschenbach sits, agitatedly, his attempt to depart from Venice thwarted by the misdirection of his luggage.

The Hotel Barber may promise to restore his youthful looks but Aschenbach’s creative spirit is sterile, guttering like the candles on his desk. His journey to the South, driven by the Strange Traveller’s encouragement that he might quench his spiritual thirst - “a leaping, wild unrest, a deep desire! […] a sudden desire for the unknown” - is an attempt to return to the past: “I am led to Venice once again,” Aschenbach sings, later fearing, “O Serenissima, be kind, or I must leave, just as I left before.” But, the sand runs steadfastly downwards.

Gerald Finley (Traveller) and Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Gerald Finley (Traveller) and Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The tremendous achievement of McVicar, his creative team and a superb, extensive cast, is to simultaneously portray the mythical aura of the city of Venice and present a disturbing portrait of a psychology laid bare. The naturalism of the 1910s setting and the astonishingly detailed realism of Vicki Mortimer’s designs are intruded by the surreal, the grotesque and the demonic. The result for Aschenbach is catastrophic.

McVicar, Mortimer and lighting designer Paul Constable exercise masterly control of these two intersecting energies, capturing in form and flux both the wretched reality and the mythic grandeur of Venice. A prevailing darkness is punctuated by sudden illuminations of light. The golden glow that greets Aschenbach when the Hotel Manager reveals the glorious view from the window of his room, for a brief moment bathes the drama in hope. But, elsewhere, for all the vivid colour that Apollo’s sunrays reveal, the Lido often seems to shimmer with a secret sickness. When the vista opens to reveal the glistening teal waters of the limitless sea, the easefulness that the brightness offers is tempered by a thick, unmoving green glow. The sky above is cloudless, but it is muted by a patina of soft grey or pink flush.

When Aschenbach arrives by gondola through the swirling mists, we can almost smell the pungency - what he later describes as a “sweetish medicinal cleanliness, overlaying the smell of still canals”. Even the clarion purity of the cry of the Strawberry Seller (Rebecca Evans) as she advertises her wares is deceptively sweet, for her red fruit is laden with choleric juices.

Gerald Finley (Gondolier) and Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Gerald Finley (Gondolier) and Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

As within Aschenbach’s own imagination and consciousness, nothing is still in the city or its lagoon. A stage-length gondola is expertly manipulated across and around the stage, twisting through the inky blackness; beyond pillars and arches which slide with the slick slipperiness of the boatman’s oar we glimpse piazzas, arches, basilicas, as our emblematic Charon carries Aschenbach towards his fate. The stagnant waters dominate, and McVicar repeatedly lets a black drop fall, to isolate Aschenbach as he sinks further into the abyss of his own mind and soul. Venetian hordes bustle and barter: tourists from across Europe gather in the cafés and on the strand; lace-sellers and glass-makers press their wares upon the repulsed Aschenbach, crowding beneath the claustrophobic arches. The individuals of the company excel, and deserving of especial note are Dominic Sedgwick’s English Clerk, who is the lone deliverer of the truth of Venice’s innate corruption, and Colin Judson’s Hotel Porter, though the latter’s middle-aged censoriousness belies the youthfulness of Mann’s original.

Amid the restlessness, though, there is statuesque motionlessness: in the form of the young Polish boy, Tadzio, holidaying with his mother, the Lady of the Pearls (Elizabeth McGorian), and his siblings. And, it is to this Hellenic apparition - what Mann’s narrator describes as ‘a statuesque masterpiece of nature’ - that Aschenbach is drawn, a vulnerable moth to a flame, increasingly convinced that, in the words of Mann’s narrator, ‘it was inevitable that some kind of relationship and acquaintance should develop between Aschenbach and the young Tadzio’.

In both novella and opera, Aschenbach is repeatedly reassured by moments, actual or self-delusory, in which the respective gazes of man and boy are locked together, and McVicar emphasises this ‘looking’ and ‘knowing’, not just through the frighteningly confident stare with which Leo Dixon, First Artist of the Royal Ballet, fixes the elderly writer with eyes that tempt and dare, but also through more subtle symbols: the small round spectacles which Aschenbach clutches and fumbles; the Brownie box-camera positioned on the beach, its single-focus lens shrouded from the sun’s heat. “So, my little beauty, you notice when you’re noticed do you?” Aschenbach’s imagined private contact with Beauty hypnotises him, inducing a mental, visual and moral stagnation: he cannot look away and, incapable of moral resolution, abandons himself to his apocalyptic destiny.

As the self-tormented protagonist, Mark Padmore gives a performance of unwavering acuity and accomplishment. For all his achievements as Bach’s Evangelist and as an interpreter of Schubert’s and of Britten’s songs, he surely has done nothing finer than this. The sweetness of his tenor, which launches lightly and cleanly into the ethereal but also communicates the pain and pathos of the actual, makes his Aschenbach a more sympathetic sufferer than we might imagine possible.

Aschenbach may be isolated from his fellow travellers in Venice but the directness of Padmore’s delivery, as he dominates the forestage, and the exemplary articulacy of his diction, hold the fictional artist and the real audience in a compelling communion. Mann described his protagonist’s inner maelstrom, with autobiographical resonance, as a combustible creativity in which the thoughts and spirit of the writer’s aged and youthful self, circled each other animatedly. [2] And, this creativity, which is both fertility and conflagration, is what Padmore, and McVicar, capture so persuasively. Padmore’s Aschenbach is not so much animated as agitated and consumed, as evidenced by the cruel glow of barber’s red cheek-rouge. The writer’s descent from novelistic speculations and the belief that beauty will enable him to “liberate from the marble mass of language the slender forms of an art”, to the desperate recognition that he “can fall no further”, is consummately controlled and paced.

Leo Dixon (Tadzio). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Leo Dixon (Tadzio). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

At the start Padmore demonstrates surprising depth and vigour of voice, as when he celebrates his reputation - “I, Aschenbach, famous as a master-writer, successful honoured, self-discipline my strength”. It’s an almost fiery self-assertion which seeks to deny and defy encroaching self-knowledge: “Why am I now at a loss? … Would not the light of inspiration had not left me.” During his Act 2 pursuit of Tadzio and his family through the fetid waterways and alleys of Venice, occasionally Padmore is subsumed within the acrid agitation. But, it is the tenor’s vocal nuance, perspicacity and control which most astounds: that, and the stamina - this is an enormously demanding sing and Padmore’s tenor is no less penetrating or well-supported at the excoriating close of the opera than it was three hours previously, when Aschenbach had sat alone in his darkened study.

‘“You see, Aschenbach has always only lived like this” - and the speaker closed the fingers of his left hand tightly into a fist - “and never like this” - and he let his open hand hang comfortably down along the back of the chair,’ reports Mann’s narrator. And, so, Padmore’s hands in many ways communicate Aschenbach’s distress and demise. Initially, he holds himself with the rigid conformity of his class, hand behind back, spine ram-rod rigid. Later, he grips his ornate leather-bound notebook, in which he seeks to translate his emotive response to Tadzio’s beauty into Platonic art, with clenched fingers; similarly, he contorts his hat’s rim and twists its crown in febrile fists. And if, when accepting the offerings of the city he exults as “Serenissma”, Aschenbach’s arms are outstretched, his palms open, then he later acknowledges his moral degeneracy with the same welcoming, or resigned, gesture.

Dixon’s Tadzio is introduced to us as a ‘real’ boy, somewhat petulant, proud and aware of the effect of his posture and pose. In fact, McVicar might have made the Polish family’s entrance more markedly gaze-grabbing, for they seem to slip into the hotel foyer without undue notice; only in Aschenbach’s feverish imagination does Tadzio almost instantly become an immortal emblem of Hellenic beauty and form. And, what is so compelling thereafter is the way the statuesque is always hovering on the cusp of motion: this Tadzio is the union of art and life for which Aschenbach longs.

Tim Mead (Apollo), Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Tim Mead (Apollo), Mark Padmore (Aschenbach). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

McVicar does not shy from the potential difficulties posed by the dance elements of Britten’s opera and, just as the opera assimilates both realism and surrealism, so the dance segues seamlessly from naturalism to artifice. In the children’s beach games, cartwheels and tumbles twist into pirouettes and entrechats, the youths’ athleticism suggesting both freedom and rebellious danger. Dixon’s duets with Olly Bell’s Jaschiu shift between aggression and sensuality. The crouches, curves and curlicues are quite simply mesmerising to behold. The Games of Apollo have a choreographic persuasiveness which beguiles. I was not entirely convinced, though, by McVicar’s notion of an Apollo-cum-gym teacher; Garsington's 2015 production seemed more forthright and more successful in this regard. But, Tim Mead was penetrating and dulcet in equal measure, if a little dour for the sun God.

From his first uncanny entrance, as the Stranger-Traveller in the graveyard, understated but suggestive in his intimations to the troubled Aschenbach, Gerald Finley injected the grotesque, ghostly and mysterious into the drama. His incarnations accrued symbolic and disturbing resonance: his lewd, lecherous Elderly Fop appalled; the vanishing gondolier alarmed; the crude balladeer - the Leader of the Players - shocked, as much for the faux-dwarf deformity that he relished brandishing as for the menacing taunt, “How ridiculous you are!”, with which he and his troupe flagellated the flinching Aschenbach.

Gerald Finley (Leader of the Players). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Gerald Finley (Leader of the Players). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The culmination of Aschenbach’s struggle to reconcile the aesthetic with the homoerotic is a Dream sequence of terrifying viscerality. Apollo and Dionysus fight for supremacy as Aschenbach writhes on a bed between them; Tadzio mounts the sleeping Aschenbach’s counterpane and strikes a pose of proud confrontation.

Lee Dixon (Tadzio). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Lee Dixon (Tadzio). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

But, McVicar and Padmore save something, perhaps everything, for the opera’s closing sequence, which is both transcendent (symbolic and mythic) and real (psychologically penetrating). Dixon’s beautifully muscular Tadzio stands upright - poised or posed - against the horizontal line where the sea meets the sky: a symbol of the Beauty which exerts a fatal fascination over Aschenbach’s fading creating imagination. The boy is a ‘perfect’ form, but one which leads Aschenbach into the formless nothingness of the Venetian waters, and on to the sea, and onwards to oblivion.

In Mann’s novella, Aschenbach strains to identify the young boy’s name: is it ‘Adgio’, or ‘Adgiu’, with a long u, the ‘euphony befitting to its object’? In the opera, the children’s affectionate “Adziù!” merges with the demonic cries of Dionysus's “Aa-oo”. The Hellenic idol, Tadzio, has a name which trickles like the sands of time: Adziù - Tadziu - Todesengel. The angel of death. But, even as we watch Padmore’s Aschenbach slump into eternal slumber, we see Dixon’s Tadzio scoop and spin, an emblem of Beauty eternal. And, we remember that Aschenbach, watching the children’s beach games, had rejoiced: “Ah, how peaceful to contemplate the sea, immeasurable, unorganised, void. I long to find rest in perfection.”

Claire Seymour

Gustav von Aschenbach - Mark Padmore, Traveller/Old Gondolier/Hotel Manager/Elderly Fop/Hotel Barber/Leader of the Players/Voice of Dionysus - Gerald Finley, Voice of Apollo - Tim Mead, Tadzio - Leo Dixon, Lady of the Pearls - Elizabeth McGorian, Jaschiu - Olly Bell, Strawberry Seller -Rebecca Evans, Lace Seller - Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha, Danish Lady - Elizabeth Weisberg, English Lady - Katy Batho, Russian Nanny - Rosie Aldridge, German Mother - Hanna Hipp, Russian Spinster - Amanda Baldwin, French Mother - Rebecca Lodge Birekebaek, Hotel Porter - Colin Judson, Boy Player - Andrew Tortise, Glass Maker - Sam Furness, Steward - Andrew O’Connor, English Clerk - Dominic Sedgwick, German Father - Michael Mofidian, Lido Boatman - Byeongmin Gil, Russian Father - Dominic Barrand, Russian Boy - Mathew Prichard, Tadzio’s Sisters - Corey Annand/Alice Guilot, German Boy - Lewis Bondu, Polish Governess - Sirena Tocco, French Girl - Adrianna Forbes-Dorant, Russian Girls - Fleur Hinchchliffe/Henrietta Howley, Dancers (David Stirrup, Arnau Velazquez, Aitor Viscarolasaga López, Hayden Davis, Euan Garrett, Matthew Humphreys, Zavier Linstrom, Leonardo McCorkindale, Casper Mott, Alfie Pearce, Harry Sills), Actors (Josephine Arden, Irene Hardy, Marcos James, Simon Johns); Director - David McVicar, Conductor - Richard Farnes, Choreographer - Lynne Page, Designer -Vicki Mortimer, Lighting Designer - Paule Constable, Associate Director - Leah Hausman, Associate Choreographer - Gareth Mole, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 21st November 2019.

[1] Translated by David Luke, ‘ Death in Venice’ and Other Stories (Secker & Warburg, 1900)

[2] ‘Sein Geist kreiste, sein Gedächtnis warf uralte, seiner Jugend überlieferte und bis dahin niemals von eigenem Feuer belebte Gedanken’, in Die schönsten Erzählungen der Welt (The most beautiful stories in the world ) (1938).

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore

November 20, 2019

A Baroque Christmas from Harmonia Mundi

Daucé and Ensemble Correspondances are among the finest of many very specialists in French baroque. Please read here about their Le Concert Royale de la Nuit, their recreation of the extravaganza with which Louis XIV dazzled his Court. They have also focused on Charpentier and in particular the Histoires sacrées (Please read more here), which have roots both in sacred oratorio and in the mystery plays of the Middle Ages. Their performances are outstanding: paragons of the art, presented with stylish flourish. This set is worth purchasing for this superlative Charpentier.

Charpentier’s patron was Marie de Lorraine, Duchesse de Guise, an independent woman whose tastes were freer and more informal than those at the royal Court. In the Pastorale sur la Naissance de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ, H. 483, Charpentier adapts the pastoral style into a work of piety, somewhat unusual at the time. Between 1684 and 1686 he created three versions, with different second parts, all of which are recorded together for the first time on this disc.

“The first part of the pastorale is imbued with solemnity”, writes Daucé. “The protagonists evoke the condition of humanity, permeated by sin, violence, darkness and death, and, in this state of extreme wretchedness, call for a divine sign bringing light, peace, justice and redemption.”. The exquisite balance of voices in the ensembles suggests rapture, and the restrained power of the soloist in “Ecoutez-moi, peuple fidele” suggests emotional authority. Charpentier’s instrumental writing is equally meticulous, marking the “contrast between the tenuousness of the recitative and the plenitude of the chorus, and above all of the device of silence”. The instrumental interlude that is the “Simphonie de la Nuit” marks in many ways the spiritual core of the first of the two parts of this Pastorale. A sublime “Paix en terre” completes the first half: voices and instruments in glorious harmony.

The second part of H.483 is a series of vignettes illustrating the Nativity scene. Particularly attractive is the section “Cette nuit d’une vierge aussis pure que belle”, the countertenor line lambent and clear, haloed by female voices. All three second parts follow the same pattern but each section within is different. In version H.483a, “We encounter the naïve and folklike elements which the first part of the work had completely avoided”, writes Daucé. “Here the musical gesture draws on the same popular imagery with which painters and designers have always depicted the Nativity scene.” Especially impressive is “Heureux bergers” for tenor with ensemble. This version ends joyously, voices accompanied by pipes, strings and percussion. “Faisons de nos joyeux cantiques”, “Menuet de la Bergère” and “ Ne laissons point sans louanges”. There are just four sections in the second part of version H.483b. “Le Soleil recommence à dorer nos montagnes” is contemplative, introducing a more reverential character. The infant Jesus is addressed as “Ouy Siegneur” framing the last section which is along as the first three sections put together, for it celebrates the “Source de lumière et de grâce”.

Also included on the Ensemble Correspondances disc is Charpentiers’ Grands antiennes de O de l’avent (1693) – ten anthems, each beginning with the word “O” on the veneration of Advent. The best -known piece on this set will be Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (Weihnachts-Oratorium) BWV 248 with René Jacobs conducting the RIAS Kammerchor and Akademie für Alte Musik with soloists Dorothea Röschmann, Andreas Scholl, Werner Güra and Klaus Häger, all then at their prime. Recorded in 1997, this performance evokes the spirit of early 18th century Lutheran piety. In modern times, we’re overwhelmed by commercialized Christmas kitsch and consumerist excess, and the banality of the seasonal music that comes with it. All the more reason then to turn to performances like this which reflect the real values of Christmas, and the promise of hope in dark times. Strong stuff, but necessary. The fourth disc on this set is a collection of pieces by Corelli (Concerto Grosso), Johann Rosenmüller, Buxtehude, Heinrich Schütz (Heute ist Christus geboren, Concerto Vocale/René Jacobs), Louis-Claude Daquin, Domenico Zipoli, and Claude Bénigne Balbastre from performances recorded between 1976 and 2004.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Baroque_Christmas.jpg image_description=Harmonia Mundi HMX2908984.87 [4CDs] product=yes product_title=A Baroque Christmas product_by=Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin; RIAS Kammerchor; Concerto Vocale; René Jacobs - Direction; Ensemble 415; Chiara Banchini - Direction; Jesper Christensen - Direction; Ensemble Correspondances; Sébastien Daucé - Direction; Cantus Cölln; Concerto Palatino; Konrad Junghänel - Direction; René Saorgin - Orgue. product_id=Harmonia Mundi HMX2908984.87 [4CDs] price=$18.69 product_url=https://amzn.to/2QENIz4November 19, 2019

Bampton Classical Opera's Young Singers' Competition - Winner Announced

The decision was reached after a superb final on Sunday 17 November at the

Holywell Music Room, Oxford. The adjudicators were renowned British singers

Bonaventura Bottone and Jean Rigby, and the esteemed accompanist and

conductor Phillip Thomas.

Lucy is awarded £1,500, Daniella and Carolyn £300 each. Dylan is awarded

£500.

This biennial competition was first launched in 2013 to celebrate Bampton

Classical Opera’s 20th birthday, and is aimed at identifying the

finest emerging singers currently studying or working in the UK. From an

initial entry of over 50 young singers aged 21-32 and after two preliminary

rounds, six were chosen to compete at the public final in the Holywell

Music Room. The finalists were Natasha Page (soprano), Jade Moffat

(mezzo-soprano), Daniella Sicari (soprano), Lucy Anderson (soprano), Giulia

Laudano (mezzo-soprano) and Carolyn Holt (mezzo-soprano). Unfortunately

Jade Moffat was unable to participate in the Final due to ill health.

Lucy Anderson’s varied programme included Smetana’s ‘Och, jaký žal!...Ten

lásky sen’ from The Bartered Bride, Fauré’s ‘Nell’ from 3 Songs Op.18, Richard Strauss’ ‘Cäcilie’ from 4 Lieder Op 27, James MacMillan’s ‘Ballad’ from 3 Scottish Songs and Ben Moore’s The Audience Song.

The judges were impressed with Lucy’s overall performance, and her