12 Mar 2010

The Nose, New York

When the orchestra re-tuned itself between the intermissionless acts of the Met premiere of The Nose last week, many in the audience were uncertain whether they were hearing practice or prelude.

When the orchestra re-tuned itself between the intermissionless acts of the Met premiere of The Nose last week, many in the audience were uncertain whether they were hearing practice or prelude.

Should they talk or should they shush? Was it time to recharge the cell phone? Would that just sound like more of Shostakovich’s raucous, blurting score?

True, no one was singing at that moment but people hardly do sing in this opera, and the leading character — Kovalyov, a faceless bureaucrat who has just awakened to discover that he is noseless as well — performs much of his role in falsetto or in oaths and exclamations and excited jabber. Paulo Szot, who’s been singing Ezio Pinza’s role in South Pacific next door to great acclaim (with a microphone) might not be impressive as Don Giovanni in so huge a house as the Met, but he’s splendid in what is largely an acting part and in a staging that stints nothing on the acrobatic shenanigans it demands of all the performers. The actual title role — Kovalyov’s nose, portrayed by Gordon Gietz — runs about committing antics, getting into fights, picking up strange women, but hardly sings at all except when impersonating an officer.

When the opera premiered in 1930, Shostakovich had the happy advantage of being certain everyone in his audience — and every literate Russian — would know Gogol’s classic short story by heart, and therefore be able to follow the surreal twists and turns of a plot that echoed Gogol’s in detail. (Those planning to attend might want to read the story, too — it’s easy to find on the Internet.) Much of the opening night audience appeared to be Russian, but those who were not were often uncertain whether director/designer William Kentridge was making fun of them or just being silly. Madly inventive as his creations are, Kentridge was following Gogol (and Shostakovich) pretty closely in the storyline, though his sets seemed more inspired by the “Constructivist” epoch of early Soviet art during which Shostakovich wrote the opera.

You may or may not care for Shostakovich’s anti-lyrical — indeed, anti-operatic — score, which lacks the yearning, emotional center that endears his Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, composed four years later, to audiences around the world. In any case, here we have an appropriate production for this strange, unoperatic opera. This isn’t the only way to present it, but it’s a way that takes the work seriously and deals with it in terms of contemporary stagecraft. The contrast to, say, the awkward, undramatic production of Verdi’s Attila that premiered at the Met a week earlier was striking: Though often handsome, nothing about that staging suited the opera being performed or helped make sense of it to a public who did not know it. The Met, it seems, will only suit the production to the work if that work is modern and alien to grand opera tradition.

Paulo Szot as Kovalyov and Gennady Bezzubenkov as the Doctor

Paulo Szot as Kovalyov and Gennady Bezzubenkov as the Doctor

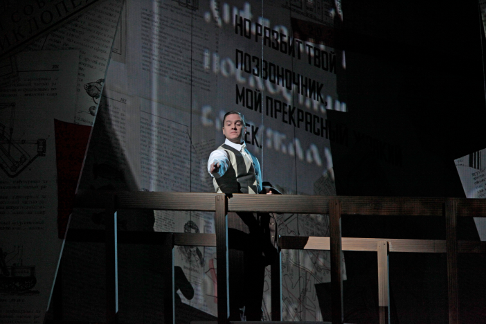

The set of The Nose is a wall of newsprint and graffiti, crisscrossed by bridges and inset with rooms, houses, offices, railway stations. The newsprint with its excitable but meaningless headlines seems to emphasize that the events of the opera are at once the very latest news and as insignificant as the filler of so much popular journalism. A man’s nose has run off — or been sliced off by a drunken barber (Vladimir Ognovenko, growling superbly) — and the hapless legal owner has pursued the runaway appendage to church and been snubbed in his polite request that it return to its place. The nose has not even admitted to working in the same bureaucratic department! And now our hero hardly dares approach the haughty lady whose daughter he was hoping to marry because — well, it’s plain as the nose on your face — he really can’t right now, can he? The authorities are unsympathetic and the newspapers will not print this story, even as a paid advertisement — he might be faking it, after all — and when the police do apprehend the runaway schnoz (attempting to leave town with a passport to Riga), poor Kovalyov has to bribe them in order to get it back. And then, at first, it won’t stay on!

Gogol’s depiction of the dullness and egocentricity of everyone in this world when faced with impossible events is precise and funny — and a forerunner of such writers as Kafka, Borges, Calvino and Barthelme. Shostakovich has set the tale with fiendish glee, in percussive explosions and astringent parody of popular song styles. The instruments often seem to sneeze or whine or fart as much as they play music. Pretty “vocalism” is a sure sign of hypocrisy — as in the case of the snobbish mother and daughter, sweetly sung by Barbara Dever and Erin Morley, or the police inspector serenely warbled by Andrei Popov — or of brainlessness, as in the charming serenade sung to balalaika by Sergei Skorokhodov as Kovalyov’s uncomprehending valet. Claudia Waite is both the barber’s shrewish wife and a bagel-seller raped by the police (a scene very like the rape of Aksinia in Lady Macbeth), Gennady Bezzubenkov is Kovalyov’s unsympathetic doctor, Adam Klein is Kovalyov’s sympathetic friend. There are twenty minor parts in the passing parade Kovalyov encounters — all too busy with their own problems to notice his — and all of them seemed to be sharing the high old time.

Gordon Gietz as the Nose

Gordon Gietz as the Nose

Yet, well before the end of the evening one tired of the shenanigans of both plot and score. Gogol’s story is short. So is the opera (less than two hours when played, as here, with no intermission), but I can’t say it flew by — it’s draining. One joke, since there is never an explanation for it, hardly sustains an entire evening.

All the singers and actors and dancers merited their applause, but the musical star was Valery Gergiev, who kept the joint jumping from start to finish with an energy that never seemed to wear out. It wore me out, but Gergiev could clearly have played a few Shostakovich symphonies as encores.

John Yohalem