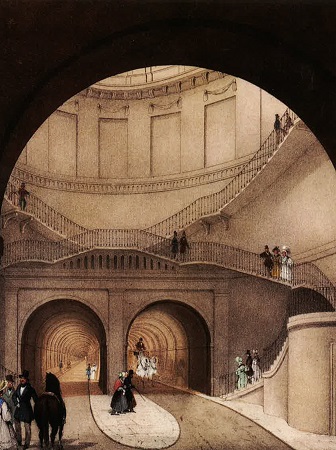

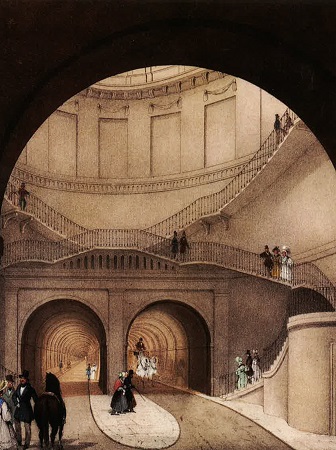

In fact, Brunel’s Grade II* listed Grand Entrance Hall has rung with the

sounds of serenades before: as Brunel Museum director Robert Hulse explained during his interval talk, it was

the venue for the world’s first underground concert party in 1827. Though

its engineering was both remarkable and rock-solid, the Tunnel’s finances

were more ropey: the money ran out before the ramps needed for horse-drawn

freight had been built and when it finally opened in 1843 it was accessible

only to pedestrians.

Ever the showman - and not deterred by the fact that he himself had

almost drowned in the shaft when a collapse during construction

resulted in a flood that killed six men - Brunel turned the Tunnel into

a sort of underground pleasure-garden. Acrobats and singers entertained

the millions of Londoners who paid their penny to enter the first ever

road tunnel under a river - it became known as the ‘Eighth Wonder of

the World’ - and wander through the bazaars, fun fairs and food stalls.

Photo credit: Archive image, Brunel Museum.

Photo credit: Archive image, Brunel Museum.

Then the steam trains came. The Tunnel was purchased in September 1865 by

the East London Railway Company and that was the end of the subterranean

show business. Until, in 2016, 190 years after construction began, the

fitting of a free-standing, cantilevered staircase made the ‘sinking’ shaft

accessible to the public once again and London gained a new underground

performance space.

On this occasion, The Opera Box had teamed up with The Music Troupe to

perform two short operas, as part of the Totally Thames Festival 2017.

As music director Edward Lambert seated himself at the piano, I

reflected that it must have taken ingenuity of which Brunel himself

would have been proud to get the Bechstein down the ‘ship-in-a-bottle’

staircase. But, the new concert space certainly provided Lambert with a

fittingly eerie performance space for his new opera, The Oval Portrait, the prose libretto of which is drawn from a short story by Edgar Allan Poe.

‘The Oval Portrait’ is one of Poe’s shortest stories, barely two pages

long. A wounded man, the Narrator, seeks shelter in a ruined chateau

where he ponders the strange paintings adorning the walls of his room.

He is particularly captivated by the astonishing verisimilitude of one

portrait, in an oval-shaped frame, depicting a beautiful young girl on

the threshold of womanhood. He finds a book under his pillow which

tells him that the young bride in the picture was the wife of the

painter; she was life-loving, jealous of his art; he was obsessed with

capturing her likeness, neglectful of his living wife. Dispirited, she

weakened but ‘smiled on and still on’, ever eager to please her

husband. When he finally finished the portrait, the painter exclaimed,

“This is indeed Life itself!” He turned to his wife, only to find that

she had died.

Lambert’s twenty-minute opera has less to say about the tale’s

philosophical intimations on the complex relationship between art and

life, and is a simpler, cautionary tale. Poe does not give us a ‘moral’

at the close; his story ends abruptly, with the book’s declaration that

the painted “turned suddenly to regard his beloved:- She was dead!” Lambert ignores

Poe’s essential ambiguity, and gives us an ‘afterword’, the first time the

voices of the Narrator and The Book - comprising a chorus of four singers -

are overlain:

Narrator: And, as I read how the last brush stroke and the list tint had

taken away the life of the lade of the oval portrait …

The Book: So let it be now that you who have read these words/ And have

gazed on the portrait of the lady shall also die.

So, instead of a reflection on the dangers of aestheticism we have a more

straightforward gothic tale. But, the five singers of The Opera Box told

this tale effectively. Samuel Pantcheff’s Narrator was intensely, vividly

alert. He swept through the lyrical vocal lines with strong

characterisation and his diction was impressively clear given the extremely

resonant acoustic. In the manner of a Greek chorus, attired in black, ‘The

Book’ processed in, smeared their faces with white streaks and then took

their places at four music stands to recite the book’s text.

The Grand Entrance Hall, Brunel Museum.

The Grand Entrance Hall, Brunel Museum.

The venue helpfully aided both blend and projection, so it’s difficult to

comment on the ‘quality’ of the singing, but the intonation was secure and

the delivery compellingly urgent. The Book’s polyphonic opening - rather

like a Renaissance motet - was controlled and the entries clear. The

homophonic repetitions emphasising the painter’s neglect of his young bride

as she sat in the dark turret for many weeks while his gaze was fixed on

his easel - he did not see that “the light in that lone turret/ Withered

the health and spirits of his bride who pined visibly to all but him.” -

became increasingly disturbing, and confirmed Lambert’s effective

text-setting.

Lambert’s piano reduction (the work is scored for piano, clarinet, bass

clarinet, viola and cello) was evocative, largely comprising extended

episodes of contrasting ‘patterns’ - anything from neoclassical Alberti

bass-type figuration to Nyman-esque repetitions. At times, the

accompaniment seemed rather dense in texture, and the rapid, pounding

chords resonated rather too loudly, competing with the rumbles of

London Overground trains overhead and leading the singers to push their

voices rather too forcefully. I don’t know how much time the company

had to rehearsal in the performance space, but a little more

consideration might have been given to the effect of the

extraordinarily generous acoustic, for the overall sound-mass was

occasionally overwhelming.

The same was true for the subsequent performance of Mozart’s

Der Schauspieldirektor

(The Impresario), in which Lambert’s enthusiastic overture established

a dynamic platform from which it was difficult for the singers to

retreat, although later arias had greater lucidity. The work was

commissioned by Emperor Joseph II to entertain the guests attending a

private luncheon in the orangery of Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, in

1786. A public opera competition was held which both Salieri and Mozart

presented one-act operas which took an ironic swipe at the world of

opera. Salieri’s opera buffa Prima la musica e poi le parole, which was full of jibes about Mozart’s frequent collaborator Da

Ponte, triumphed over Mozart’s

Singspiel (the composer called it a ‘comedy with music’).

A parody on the professional and personal vanity of singers and other

theatre-folk,

Der Schauspieldirektor (given here in a new translation by director Mark Burns, which teases

out some topical tropes) presents a theatre director, Mr Frank

(Pantcheff), who is having troubled raising funds to engage some new

actors. Mr Phil Anthropist (Daniel Joy) promises to help but only if

his lover, Madame Heartfelt (Jennifer Witton), can be the prima donna.

Along come Miss Silverklang (Elizabeth Karani) and Mr Buff (James

Schouten), to vaunt their vocal wares. Exasperated by their egos and

eccentricities, Mr Frank is ready to give up but agrees that the

audience should decide who should be hired.

Witton coped well with the diva’s challenging runs and hit the

stratospheric heights with sparkle, but the acoustic magnified every

rough edge on the way up: less really would have been more - the venue

would have done all the work. Karani, her fitness-freak challenger, was

her match in their vocal duels, displaying lots of vocal colour and

evenness across the registers. Exuberantly attired in mis-matched pink,

yellow and scarlet Daniel Joy was a self-serving, self-absorbed

‘philanthropist’ whose appealing tenor was complemented by dramatic

nous. I’m not sure I’d describe James Schouten as a buffo bass, but his

Mr Buff had plenty of puff and bluff. Pantcheff provided strong focus

and presence for the rest of the cast, and his extended stretches of

dialogue were fluent and engaging.

There were plentiful gags about singers’ status, salaries and

self-love, as well as the relevance of opera in the modern world. But,

while Burns can turn out a neat triple-rhyme and tap fruitfully into a

contemporary lexicon, his direction made less of an impact. Arias

tended to be delivered from the centre of the stage-space, with the

rest of the cast manically mincing, arm-waving and engaging in

histrionics behind, with little meaningful interaction between them.

There was potential here for some really sharp satire and tightly

focused drama but, in the event, we had horse-play and lightweight

cattiness.

Moreover, the company need to give some thought to what might be termed

professional procedures. After Mr Hulse’s interesting but extended

mid-way presentation, I assumed that we were ready to get on with the

show, especially as we were invited at its conclusion to applaud and

welcome back The Opera Box. In the event, another 25 minutes passed

before things got underway, during which time a stage-hand had wandered

about with some chairs and seemed to be preparing a new set, but got

distracted by some friends in the audience. It’s all very well to

cultivate a ‘friends and family’ ambience but, given that the costume

changes must have taken just a few minutes, when barely 60 minutes of

music extends to an event lasting nearly two hours you are in danger of

stretching the audience’s patience.

That said, the talented young cast sang and hammed valiantly. The Opera

Box put on a good show which was welcomed by an appreciative audience.

Claire Seymour

Edward Lambert - The Oval Portrait: Narrator - Samuel Pantcheff, The Book - Jennifer Witton, Elizabeth Karani, Daniel Joy, James Schouten

Mozart - The Impresario: Madame Heartfelt - Jennifer Witton, Miss Silverklang - Elizabeth Karani, Mr Phil Anthropist - Daniel Joy, Mr Frank - Samuel Pantcheff, Mr Buff - James Schouten

Director - Mark Burns, Music Director/Pianist - Edward Lambert,

Lighting Designer - Fridthjofur Thorsteinesson, Assistant Director -

Morgan Richards

Brunel Museum, Rotherhithe, London; Thursday 7th September

2017