December 30, 2005

Washington Opera to Perform Wagner Series

WASHINGTON, Dec. 30, 2005(AP) An Americanized version of Richard Wagner's "The Ring of the Nibelung," a series that long has been a symbol of German nationalism, will open March 25 with the Washington National Opera's production of "Das Rheingold."

WASHINGTON, Dec. 30, 2005(AP) An Americanized version of Richard Wagner's "The Ring of the Nibelung," a series that long has been a symbol of German nationalism, will open March 25 with the Washington National Opera's production of "Das Rheingold."

Berg's Wozzeck at the Met — Three Reviews

An Expressionist Fervor, Illuminated by Levine

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI [NY Times, 29 December 2005]

If James Levine could zap himself back in time and conduct the premiere of any opera in history, what among his favorites might he choose? Perhaps the Vienna premiere of Mozart's "Nozze di Figaro." Or the Milan premiere of Verdi's "Otello." How about the Munich premiere of Wagner's "Meistersinger," a work he conducts magnificently? I love the idea of Mr. Levine's giving a sublime account of this humane comedy and forcing the anti-Semitic composer to confront his twisted prejudices.

Click here for remainder of article.

Levine's Fine Judgment

BY JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 29 December 2005]

James Levine did what he was expected to do on Tuesday night: conduct a superb performance of Berg's "Wozzeck." The Metropolitan Opera has revived Mark Lamos's production of 1997.

Click her for remainder of article.

Wozzeck, Metropolitan Opera, New York

By Martin Bernheimer [Financial Times, 29 December 2005]

'Tis the season to be jolly. But no one seems to have told that to the masterminds at the murky and quirky Metropolitan Opera. Apart from a few flighty Fledermice and loony Lucias, the final weeks of 2005 are dominated by bleakness and gore. Nearing the end of its premiere run, Tobias Picker's sordid An American Tragedy served as a matinee-broadcast vehicle on Christmas Eve. Tuesday night Alban Berg's eternally grim Wozzeck returned in preparation for transmission on the afternoon of New Year's Eve. Luckily it is a very good Wozzeck.

Click here for remainder of article.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/bergmain.jpg

image_description=Alban Berg

December 29, 2005

Mario Del Monaco at the Bolshoi

More than official Decca sets, where voices often were somewhat equalized, it shows the power of the tenor’s voice which often overwhelms most of the others on the scene. Pavel Lisitsian, who is a bit of a cult figure among Western collectors as he was so rarely allowed to leave the Soviet Union — one Met-performance in an untypical Amonasro-role — shows a fine though very idiosyncratically coloured voice; but it is clear from this recording that the voice is less powerful than on records. And one notes too that though the top is brilliant there are almost no low notes and his voice is simply not at ease in this role which better suits a bass-baritone. Irina Maslennikova as Micaëla has a rather small shrill lower middle voice and is dwarfed by Del Monaco but gets stronger the higher she sings. The only person on the scene who could give Del Monaco tit for tat is the formidable Irina Archipova, though as a result she sometimes forces the voice and becomes rather vulgar.

By 1960 decades of isolation resulted in Soviet singers more and more going for noise than for musicality. Lemeshev, Kozlovsky, Obukova all studied before the war; often with teachers who themselves had lived through extensive contacts in the West. By the time Archipova studied most of those teachers were deceased and almost no Western records were available. An exception to that rule were the movies by Mario Lanza and Mario Del Monaco, as Soviet censure considered them to be completely harmless. And a lot of Soviet singers took their clues from these examples.

And it was not the La Scala visit of 1964 with Carlo Bergonzi that changed Russian perception on Western singing. After all only members of the party’s nomenclatura got tickets for those much heralded performances; but ordinary Russians didn’t go crazy for Bergonzi, as he was just another tenor and not a star like Mario Del Monaco who had played the title role in Italy’s answer to Lanza’s The Great Caruso (in reality he only lent his voice) and in those popular movies on Verdi , Mascagni and that German pot boiler “Schlussakkord”. Therefore the coming of Del Monaco to Moscow was a major event in 1959 and the tenor met all expectations as he gave them what they thought was the one essential element of tenor singing: strong top notes, kept on as long as possible.

Del Monaco must have felt he was returning to his early days. At that time every high note in the Italian province theatre was still roundly applauded, if necessary in the middle of an aria or a duet and the Muscovites can easily compete with many an Italian theatre. As a result Del Monaco, who even at his best behaviour was always milking for applause, feels no restraint at all. There is of course no denying the richness of the sound, the formidable beauty when he remembers to sing like he did in some of his best moments with strong conductors. But time and again the coarseness takes over and he often uses an ugly glottal stop. In the second act he really has a field day, changing from Italian to French and vice versa whatever part of the role he remembers best in one of these languages. And that fine conductor Melik Pashaev has the great honour to accompany the tenor and keep the orchestra in check so that it patiently waits for the moment Del Monaco has finished his note and it can proceed further. Anyway, the Russians at the time were wildly happy as proven by the well-known video-recording of this performance (2nd and 4th act only).

The Pagliacci of a week later is stylistically better as he can sing in his own language in a role that will accept some sobs. And sob he does whenever he has the opportunity. And once again he is above all showing off his volume and his top notes. “Vesti la giubba” starts off really well, showing the intrinsic beauty of the voice in his last year of grace as all real Del Monacistis will agree with. But then, just after his “Ridi Pagliaccio” he breaks the line in “sul tua amore infranto” by taking a deep breath between “amore” and “infranto” just to score an extra-decibel on that last word. His “No, Pagliaccio non son” starts well and even a little bit restrained; but in the middle section of “Sperai, tanto il delirio” he simply reverts to shouting. The end of the opera is well worth hearing. Del Monaco has decided to improve the score and correct Leoncavallo’s forgetfulness. After “La commedia è finite” his shouts of Nedda followed by magnificent sobs repeated for half a minute probably led to her resurrection. This time Leocadia (and not Irina) Maslennikova has the honour of assisting the tenor and she has a metallic strong voice. The Tonio, Alex Ivanov, was probably a KGB-informer as I see no other reason why he got this role. He is wretchedly bad, more speaking in a dry tone, than singing.

The bonus is spread over two CD’s and is a recital Del Monaco recorded for Melodia on a ten-inch record. The arias from Otello, Tosca and Pagliacci are fine though he has sung them better for Decca; especially the Pagliacci-prologue but I’m sure Del Monaco-lovers will definitely enjoy the Moscow-version with a big “hahahaha” in the middle of the aria. And I’m surprised that Myto, always looking for the best sound possible, couldn’t find a better copy of that record as there is a giant tick in the middle of the recording that makes you sit up.

Jan Neckers

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Del_Monaco_Bolshoi.jpg

image_description=Mario Del Monaco at the Bolshoi

product=yes

product_title=Mario Del Monaco at the Bolshoi

(1) Georges Bizet: Carmen

(2) Ruggero Leoncavallo: Pagliacci

product_by=(1) Mario del Monaco; Irina Archipova; Irina Maslennicova; Pavel Lisitian, Orchestra e Coro dell’Opera Bolshoi di Mosca, Alexandr Melik Pashayev (cond.) Live recording: Moscow, June 13, 1959.

(2) Mario del Monaco; Leocadia Maslennicova; Alex Ivanov; Orchestra e Coro dell’Opera Bolshoi di Moscow, Basiliev Tieskovini (cond.). Live recording: Moscow, June 20, 1959.

product_id=Myto 3MCD053311 [3CDs]

Macabre, magical and magnificent

[Daily Telegraph, 29 December 2005]

[Daily Telegraph, 29 December 2005]

Rupert Christiansen reviews Hansel and Gretel at the Leeds Town Hall

With its gruesome fascination for the evils of starvation and gluttony, not to mention its rampant depiction of child abuse, Hansel and Gretel ranks among the more macabre of Christmas pantomimes.

ENO changes tune on music director

· Caetani may have been limited to six weeks a year

· Caetani may have been limited to six weeks a year

· Questions raised over 'coronation' appointments

Charlotte Higgins [The Guardian, 29 December 2005]

Things could not get much worse for English National Opera. But having lost its artistic director a month ago, and its chairman a week ago, yesterday the company managed to lose its music director - before he had even taken up his job.

Barenboim hints at La Scala encore

· Conductor fuels rumours he will be musical director

· Conductor fuels rumours he will be musical director

· Milan in raptures over his Christmas concert

John Hooper in Rome [The Guardian, 29 December 2005]

Speculation is rife in the Italian music world that Daniel Barenboim intends to crown his career by becoming musical director of the world's most famous opera house, La Scala in Milan.

SCHREKER: Christophorus oder “Die Vision einer Oper”

How easy it might be to overlook this lesser-known Schreker opera, composed in 1928 and dedicated to Schreker’s good friend Arnold Schoenberg, here in its recorded debut. It has a quite curious libretto, complex and multilayered, and Schreker moves between what are at times quite disparate styles. The whole thing comes off at first blush like a kind of soup made of the leftovers of earlier post-romantic and expressionist idoms, and were it not for our warming sympathies on repeated listening, we might have happily consigned it to the dustbin of history.

Repeated listenings have not been sufficient to entirely sort out the improbable libretto. The story, set in large part in a sort of composer’s atelier, concerns three principal characters, Anselm, Lisa, and Christoph. Anselm is at work upon an opera about the legend of St. Christopher, in which Anselm himself, Lisa, and Christoph, a fellow composition apprentice, are all to play roles. Christopher, Christoph, fiction, real life–the thing’s a narrative muddle, from the dramatic Prelude on. The story comes off like a befuddled Pirandello: half a dozen characters, having found a librettist, now desperately in search of a composer.

Despite the curious nature of the narrative–no let’s get this straight, indeed uninhibited by the narrative–Schreker is in close to full form here. The score is well turned, moments of Berg’s Wozzeck blended with the later Strauss–Ariadne or Arabella . The characters are probable, believable in a kind of irritating way, since they demand a better story line. Anselm’s character, in its developing anger and cynicism, is a model of modernism, and his impassioned interactions with Lisa in Act I are very good operatic duets.

The opera is in two short acts, the first act and its dramatic prelude running just shy of an hour, the second running on 40 minutes. The latter is the tighter of the two: it contains several scenes of good drama and the run away characterizations of the first act settle down here into real persona. Throughout the opera, there is an unusual amount of dialogue, much of it accompanied–a sort of modernist melodrama, where spoken lines are cushioned by a lush, often quietly dissonant orchestral pad. In the whole of Act II, in fact, there is really only one “number,” per se, Scene 3 (track 4), Rosita’s lied. This is Schreker’s portrait of jazz (worthy of comparison with jazz portraits by Weill and Stravinsky), with lisping saxophones and a limpid barrelhouse piano. The lied, in fact, is structured like a duet, and set to a divided stage, on one side Rosita, on the other Christoph in a kind of evaporated opium dream that gradually takes over the stage. Elsewhere operatic “numbers” make an initial appearance, seem to hesitate, and then morph into something else. Now this is nothing new; in German opera, it has been going on at least since Weber’s Euryanthe . But Schreker turns it to his own modernist advantage. Scenes 5 and 6 constitute a lengthy operatic conjuring with a half a dozen characters (and what sounds like a theramin [but may be only a musical saw] and a creepy mandolin obligato) that, in its intensity, harkens back to Weber’s Freischutz Wolfglen scene. And there is a tiny Kinderlied (scene 8), reminiscent of Wozzeck , as well as a lengthier song for child’s voice in the Epilogue, responding in similar fashion to a hazy lied-like passage for Christoph (tracks 14 and 15).

The orchestral writing throughout the work is nothing short of excellent. Orchestral interludes, motivated or not, crop up repeatedly, and beg symphonic treatment. One of the longest of these extends from the end of scene 8 into scene 9 and then moves smoothly into a curious orchestral recitative of a selection from Lao Tzu, before moving into the conclusion of the opera.

On the whole the performance is smooth and competent, if the voices are mostly unexceptional. Hans Georg Ahrens does a most sympathetic Anselm, Susan Bernhard an occasionally uneven Lisa, and Joerg Sabrowski a rather cardboard Christoph. Two voices stand out as very good: Roland Holz, in a speaking role as the critic Starkmann, spoken with a lovely Berliner nasal, gritty and nicely irritating; and Hans Georg Ahrens, bass, as the composition master Johann, with a deep, noble resonance. The live recording is sensitive, with a minimum of boots clumping around on stage and a good set of microphones in the pit.

The booklet is of good use here, explaining the opera’s misfortunes in terms of the years after the First World War, Schreker’s career, the stylistic turns of fortune in which the opera got caught up, and a nice excurse on the stylistic politics of the day. For good measure, the booklet reproduces an “Introduction” penned by the composer, which would seem to explain the need for this twisted narrative (sometimes in unabashedly personal terms), but instead merely adds to the confusion. Schreker’s introduction reads like an apology, but in truth the only thing to be regretted here is the storyline.

It would be a shame to make this work simply an historical artifact, a product, warted, of its day and its composer’s traumas. There is enough good writing here, however, to make the opera worthy of our admiration without recourse to history. What we need now (now that most of Schreker’s opera are available in modern scores and good recordings) is a critical overview. It would be good to compare Christophorus with the “hits,” the better known Schreker operas such as Der ferne Klang , Die Gezeichneten , and Der Schatzgräber , not merely in historical terms (a subject interesting in their own right) but as possible entries into the canon of twentieth-century opera.

This recording stems from a three-part Schrecker cycle at the Kiel Opera from 2001 to 2003, under the artistic director, Kirsten Harms, the other two operas being the premier in full score of Die Flammen , Schreker’s first opera, and Das Spielwerk und die Prinzessin from 1913, perhaps the moment at which Schreker’s career was in fullest flower. The latter two operas are also available on the CPO label.

Murray Dineen

University of Ottawa

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/christophorus.jpg

image_description=Christophorus oder “Die Vision einer Oper”

product=yes

product_title=Franz Schreker: Christophorus oder “Die Vision einer Oper"

product_by=Ahrens, Bernhard, Sabrowski, Chafin, Klein, Gebhardt, Schöpflin, Pauly, Arnold, Kieler Opernchor, Kieler Philharmoniker, Ulrich Windfuhr (cond.)

product_id=cpo 999-903-2 [2CDs]

December 28, 2005

SPITZER & ZASLAW: The Birth of the Orchestra — History of an Institution, 1650-1815

The Birth of the Orchestra — History of an Institution, 1650-1815 by Spitzer and Zaslaw is an outstanding study of the origins of one of the defining ensembles for serious music. As the authors summarize the various elements that play into the evolution of the orchestra succinctly:

Besides the instruments and performers in the pit or on the stage, the process [that culminated in the modern orchestra] involved repertories, performance practices, administrative structures, system for training players, techniques of scoring and orchestra, the acoustics of theater and concert halls, and many other things. Finally, the birth of the orchestra as a matter of people’s beliefs – what people thought orchestras were and what orchestras meant. (p. 531)

In light of the rich traditions that combine in the modern orchestra, those beliefs mean a lot and evoke much fine music. The evolution of the orchestra into the ensemble as it is known today is part of a tradition that continues, and this book is evidence of its persistence in culture. At the same time, this book addresses a need in music history to trace the evolution of the orchestra from the seventeenth century to the early nineteenth, as this grouping took shape for various kinds of music in multiple venues. At the same time the study benefits both from fine research and excellent writing, two aspects of scholarship that do not always coincide as well as they do in this volume.

While the focus of the book is the period identified in the subtitle, the authors have wisely chosen to begin with a consideration of the idea of the “orchestra” as ensembles were envisaged as part of opera at the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Taking as a point of departure various operas that dealt with the Greek myth of Orpheus and Euridice, Spitzer and Zaslaw identified the scope and size of the instrumental ensembles involved, from the relatively smaller forces associated with Peri’s Euridice (1600) to a slightly larger grouping for Monteverdi’s Orfeo (1607). In moving through the seventeenth century, composers returned to the story to create their version of the story in opera and in doing so involved increasingly larger and diverse ensembles to accompany their works. Thus, the orchestra that Lully required for Le ballet des muses (1666) presumes a more clearly defined core of string instruments, the sound of which would be enhanced by winds, brass and percussion for Haydn’s opera Anima del filosofo (1791) – the forces required for the latter work resembling more the sound associated with the so-called classical orchestra.

This exploration of the nature of the orchestra begs the questions that authors address about what to call the earlier ensembles that functioned in the manner of a modern orchestra. The historical perspective that emerges from this discussion is important for distinguishing between the groups of instrumentalists that were used to accompany opera and discussing in substantively the nature of the orchestra as it became understood in the Common Practice Era. At the same time, the discussion of the word “orchestra” offers some insights into its meaning, as the ensemble took shape as a vehicle for music performance that also served as a focal point for a critical body of music literature.

The authors also discuss the transition to the formal orchestra in the chapter on “Pre-orchestral Ensembles,” a deftly written article on the growing place of instrumental performance from the late-sixteenth century to the late seventeenth. This chapter offers a masterful perspective on the stylistic choices that helped to shape the evolving orchestra, as decisions about performing the music influenced the literature that also took shape at the time. While the annotations document the information, they should also point the reader to exploring the volume of research on this topic.

In the subsequent chapters, Spitzer and Zaslaw discuss the various ways in which both composers and conductors dealt with orchestras. After discussing the role of two major figures, Lully and Corelli, the authors review the various national styles one by one, so that the reader gains a sense of the treatment of the orchestra in Italy alongside the function of the ensemble in France. The chapter on Germany is notable for the distinctions the authors make about the circumstances in the orchestra found its place in the German courts and principalities as the various groups changed from emblems of modernity based on Italian and French models to increasingly strong components of native German culture. The strength of their influence was such that by the late eighteenth century the German orchestras were a model for the rest of Europe.

Likewise, the discussion of the orchestra in England offers some insights into the cultural milieu in which it gained ascendancy as part of the country’s contribution to music-making. The inclusion of references to the state of orchestras in the colonies is welcome, as it shows the ways in which music arrived in North America. Such connections are known, but not often expressed well enough to suggest the continuity which existed as the arts took root in the new world. The situation resembles that which exists in South America, where opera took root from the Iberian colonization and developed quickly in that soil. At the same time, the discussion of festival orchestras and their place in the musical culture of England and on the Continent is another element of this study.

At the center of the book, the authors expound upon makeup of the classical orchestra (pp. 306-42) which is supported by several chapters that deal, in turn, with seating arrangements and acoustics (pp. 343-60), performance practices (pp. 370-97), the role of the orchestral musician in the eighteenth century (pp. 398-435), and the technique of orchestration (pp. 436-506). This section of the book stands apart form other studies for the clarity which guides the writing. While some might quibble with a few details, the exploration offers a sound treatment of the topic that should be a model for other, similar studies.

In addition to the tables and graphs that support the research, the authors have selected some excellent illustrations to reinforce the points that they make in their texts. Their comments about the various plates offer some guidance toward understanding the images, especially the ones that have some telling iconography about the placement and relative size of ensembles (a useful point occurs on pp. 345-46). In fact, it is laudable that Oxford University Press used a relatively larger size for this book than some of its other monographs, since it afford a more comfortable presentation of the various illustrations in the book.

The music examples are equally well-chosen and reflect the focus that occurs elsewhere in the book. Eschewing some recent tendencies to publish extensive passages in monographs and articles, the authors use the examples to fine effect. It is laudable when the examples invite further exploration of the very points that the authors want to make. The authors and the Press wisely chose to have the examples set uniformly, thus making them immediately legible. Again, they avoid the temptation of inserting facsimiles of historical prints that represent a variety of hands and styles. With the uniform presentation that occurs here, the examples comfortably support the text and the points that they authors want to make.

Further, the bibliography (pp. 553-91) is significant for the depth of scholarship it represents. The literature represents some of the finest research on the orchestra for the period discussed, including some classic articles by such figures as Emanuel Winternitz, Thurston Dart, Mary Cyr, Henry Prunières, and others, along with some fine recent writers as Luca Della Libera and Kate Van Orden. As lengthy as the references are, the authors wisely choice to avoid segmenting the information into what are ultimately arbitrary categories. Thus, readers will find in the bibliography literature from the period, like Charles Burney, Samuel Pepys, Johann Mattheson, Leopold Mozart, alongside more modern sources. In some cases there citations refer not to only primary and secondary literature, but also, editions, like the oeuvres of Arcangelo Corelli. Those intrigued by this book may want to explore the bibliography to become acquainted further with other research and materials on the topic covered in this volume.

All in all, this fine study should be of interest to scholars, performers, and anyone interested in understanding more about the origins of the orchestra and the way it evolved. Thoroughly documented, with much information in tabular form, the scholarship is highly accessible. As valuable as this work is as an exemplary piece of scholarship, its accessibility makes it useful to anyone interested in the orchestra as a cultural institution. To see the directions that intersected in Western culture as the orchestra took shape gives a glimpse at the incredibly rich traditions that tie together generations of lives, inestimable talent, social and political forces, and other elements. Besides the extraordinary literature that it produced, the strong tradition of orchestral performance is a crucial part of culture. It is fortunate, indeed that Neal Zaslaw and John Spitzer devoted years to distill that sense in this important new book.

James L. Zychowicz

Madison, Wisconsin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Birth_orchestra.jpg

image_description=The Birth of the Orchestra — History of an Institution, 1650-1815

product=yes

product_title=John Spitzer and Neal Zaslaw: The Birth of the Orchestra — History of an Institution, 1650-1815.

product_by=Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

product_id=ISBN13: 9780195189551 | ISBN10: 0195189558

price=$45.00

product_url=http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/Music/MusicHistoryWestern/?view=usa&ci=0195189558

GOUNOD: Faust

First performance: 19 March 1859 at Théatre-Lyrique, Paris

Principal characters

| Marguerite | Soprano |

| Faust | Tenor |

| Méphistophélès | Bass |

| Valentin | Baritone |

| Wagner | Baritone |

| Mr Siébel | Soprano |

| Marthe | Soprano |

Synopsis

Act I

Faust's cabinet.

The philosopher Faust is profoundly depressed by his inaptitude to reach fulfillment through knowledge and thinks of committing suicide. He pours the contents of a poison phial in a cup, but stops suddenly drinking the deadly liquid when he hears a pastoral choir. He damns happiness, science and faith and calls on Satan to guide him. Méphistophélès appears (duet: " Me voici "). Faust confesses to him that he looks for youth, more than wealth, glory and power. Méphistophélès agrees to fulfill the wishes of the philosopher, in exchange for his services in the infernal regions. As Faust hesitates to accept this condition, Méphistophélès has Marguerite appear to him sitting at her spinning wheel. Faust signs then the document and is transformed into a noble young person.

Act II

The carnival at the city gates. One sees a cabaret on the left.

The curtain rises on a joyful choir of students, soldiers, bourgeois, girls and stout women (choir: " Vin ou Bière "). Valentin enters, holdin in his hand a medal which his sister Marguerite gave to him; he is about to leave for war, and is giving instructions to his friends, notably to Wagner and Siébel, so that they take care of her. They sit down to take a last glass. Méphistophélès appears suddenly, and amuses them with a song on the golden veal (round dance: " Le veau d'or "). Valentin gets angry when Méphistophélès talks lightly about his sister, but his sword breaks in the air before reaching its target. Confronted with a supernatural power, Valentin and his companions brandish crossshaped knobs of their swords in front of the devil (choir: " De l'enfer "). Méphistophélès remains alone, soon joined by Faust and by a group of village waltzers (waltz and choir: " Ainsi que la brise légère "). When Marguerite appears among them, Faust offers her his arm; she refuses with modesty and goes away deftly.

Act III

Marguerite's garden.

Siébel is in love with Marguerite and sets down a bouquet for her (stanzae: " Faites-lui mes aveux "). Faust and Méphistophélès enter the garden; while the devil is in charge of finding a present for Marguerite, Faust shouts out to Marguerite's house and to the defending embrace of nature (cavatina: " Salut, demeure chaste et pure "). Méphistophélès returns and sets down a casket with jewels for the girl. Marguerite arrives, wondering who was the young gentleman who approached her earlier. She sings a ballad on the king of Thulé, discovers the bouquet and the casket of jewels and, quite incited, tries earrings and necklace (scene and air: " Il était un roi de Thulé "). Marthe, Marguerite's governess, tells her that these jewels have to be the present of an admirer. Méphistophélès and Faust join the two women; the first tries to seduce Marthe, while Faust converses with Marguerite, who shows herself still very reserved (quartet: " Prenez mon bras "). While Faust and Marguerite disappear for a moment, Méphistophélès casts a fate to the flowers of the garden. Marguerite and Faust return and she allows Faust to kiss her (duet: " Laisse-moi, laisse-moi, contempler ton visage"); however, she steps back suddenly and asks him to go away. Convinced of the insignificance of his efforts, Faust is resolved to abandon his project altogether. He is stopped by Méphistophélès, who orders him to listen to Marguerite at her window. When hearing that she hopes for his quick return, Faust shows himself and takes her hand; as she drops her head on Faust's shoulder, Méphistophélès cannot refrain from laughing.

Act IV

Marguerite's room.

Marguerite has given birth to Faust's child and is ostracised by girls in the street. Saddened because Faust abandoned her, she sits down at her spinning wheel (air: " Il ne revient pas "). Siébel, always faithful, try to encourage her. A square. The return of Valentin is announced with soldiers' walking, and it becomes clear that things are going to deteriorate. Having heard Siébel's evasive answers to the questions he asked about his sister, Valentin rushes furiously in the house. While he is inside, Méphistophélès satirically plays the role of lover, giving a serenade under Marguerite's window (serenade: " Vous qui êtes l'endormie"). Valentin reappears and demands who took his sister's innocence. Faust pulls his sword; during the ensuing duel, Valentin is lethally wounded. As he dies, he throws back all responsibility on Marguerite and damns her for the eternity. A cathedral. Marguerite tries to pray, but is prevented from it by,first, the voice of Méphistophélès, then by a devils' choir. She finally succeeds in finishing her prayer, but faints when Méphistophélès releases a last curse.

Act V

The mountains of the Harz. The night of Walpurgis.

One hears a choir of will o' the wisps when Méphistophélès and Faust appear. They are quickly surrounded by witches (choir: "Un, deux et trois"). Faust tries to run away, but Méphistophélès hurries to take him somewhere else. A decorated, populated cave of queens and courtesans of the Antiquity. In the middle of luxurious banquet, Faust sees Marguerite's image and demands for her. While Méphistophélès and Faust leave, the mountain closes and the witches return. The inside of a prison. Marguerite is imprisoned for killing her child, but, thanks to Méphistophélès's help, Faust obtains the keys of her cell. Marguerite wakes to the sound of Faust's voice; they sing a duet of love (duet: "Oui, c'est toi que j'aime") and Faust asks her to run away with him. Méphistophélès appears and begs Faust and Marguerite to follow him. Marguerite resists and calls for divine protection. Desperate, Faust watches and falls to his knees in prayer, while Marguerite's soul rises towards heaven (highlight: "Christ est ressuscité").

Synopsis courtesy of Charles Gounod — His life, his works.

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Gounod_Henri_Lehmann_1841.jpg

image_description=Charles Gounod by Henri Lehmann, 1841

audio=yes

first_audio_name=Charles Gounod: Faust

first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Faust1.m3u

product=yes

product_title=Charles Gounod: Faust

product_by=Nicolai Gedda, Heather Harper, Nicolai Ghiaurov, Robert Massard, Africa De Retes, Luisa Bartoletti, Orchestra e Coro del Teatro Colon, Gianandrea Favazzeni. Live performance 8 May 1971, Buenos Aires.

Review: 'Wozzeck' Works for the Holidays

By RONALD BLUM [Associated Press, 28 December 2005]

By RONALD BLUM [Associated Press, 28 December 2005]

NEW YORK - Berg's "Wozzeck" does not fit with the frothy and festive fare many classical music institutions regularly offer during the holiday season.

ENO woes continue with new sacking and strike

By Jack Malvern [Times Online, 28 December 2005]

By Jack Malvern [Times Online, 28 December 2005]

English National Opera received a double blow today when its newly appointed music director was sacked weeks before he was due to start and its staff voted overwhelmingly to go on strike.

Celebrating a Quarter-Millennium of Mozart

Gaby Reucher (jen) (Deutsche Welle, 28 December 2005)

Gaby Reucher (jen) (Deutsche Welle, 28 December 2005)

2006 is the 250th anniversary of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's birth, and classical Europe is looking to party. A look at one of the geniuses of the German-speaking world.

Unhappy birthday? It's his 250th anniversary, but Mozart is too 'chocolate-boxy' for Radio 3

By Ciar Byrne [The Independent, 27 December 2005]

By Ciar Byrne [The Independent, 27 December 2005]

For lovers of Bach, Radio 3's decision to play the composer's entire works was a stroke of genius, garnering glowing responses from listeners and critical acclaim.

Music writers put an ear to the ground

By FT music critics [Financial Times, 27 December 2005]

By FT music critics [Financial Times, 27 December 2005]

The mighty Metropolitan

By Martin Bernheimer

A new year beckons, a year rife, no doubt, with joy and rapture, disappointment and disenchantment. It is always like that in the wonderful, irrational world of opera.

December 27, 2005

SCHUBERT: Winterreise

Those familiar with René Kollo’s work might associate him more with opera, but he has recorded other kinds of works as well. This release is Schubert’s Winterreise is a recent effort that was created for and released by Oehms in 2004. Kollo recorded it between 17 and 19 February. His statement about the performance is included in the booklet that accompanies the CD, and in it he calls attention to his perspective of the music. As he states,

With my interpretation of Winterreise, I hope to present listeners with a new view of Schubert’s Lied cycle. For me, Winterreise is not primarily a story of farewell and the longing for death. I see it much more as the wrathful flight of a man, who – beset by the realities of class differences – must leave the one he loves. He fails in the face of social tensions; the rich girl is unattainable for him. . . . At the end, I sing of a beginning – not of a standstill. In the person of the hurdy-gurdy grinder, the search finds one who has certainly traveled a similarly fateful path. He now sings his songs with him. The mood is lighter and tends slightly towards optimism. . . .

Yet in concluding his remarks, Kollo acknowledges that the CD is expressly intended as a fund-raiser for the Deutsche Kinderhilfe Direkt (the German Direct Children’s Aid Association). The purpose is stated on the cover of the CD, and the first thing that one finds inside is the statement by Georg Ehrmann that the purchase of the recording is intended to benefit German Children’s Aid, with the address, contact information and even Konto codes for further donations. As a means of calling attention to a cause, this is certainly a unique involvement of the arts, which are often concerned with raising money for their own purposes.

Notwithstanding the reasons for the recording, it merits attention for the mature and well-thought perspective that Kollo brings to a familiar work. This is a sound approach to the work that the performers have borne out well in this recording. As a studio recording, the performance is lacks hall noise and other distractions that sometimes occur, even in the best of circumstances. Yet the sound levels are sometimes extremely close to the voice, thus missing the ambiance that comes from having some distance between the performances and the microphones. The kind of resonance that has been preserved in some other recordings of Schubert’s Lieder is not easy to find on this CD, and it is sometimes difficult to hear the accompaniment blend with the voice.

As to the accompaniment, the performance on this recording suggests that Oliver Pohl has much to offer in the area of Lieder. The nuances that Pohl brings into the fourth song, “Erstarrung,” the one which Kollo holds to be the turning point in the cycle, is effective. This stands in contrast to the sometimes relentless execution he gives to the first three songs, the ones that Kollo states depict the angry flight [zornige Flucht] of the protagonist. The lighter tone that the performers introduce after the first songs culminates in an exceptionally thoughtful conclusion, with the final song “Der Leiermann” fading away in a manner that fully contrasts the opening pieces. Pohl is responsible for this convincing dénouement, and he has clearly worked out the interpretation with Kollo. Overall Pohl supports Kollo solidly, matching the tenor’s intensity with similarly strong playing, which is evident in the exposed passages for piano, like the one in the center of “Der Lindenbaum.”

The liner notes for the CD include the full text of the song cycle, but without any translations. With a familiar work like this, the lack of a translation is not a problem, but it points, perhaps, to the intended audience of the CD in Germany or, at least, in German-speaking countries. In fact, the note by Pohl appended to his biography reinforces the intention of the performers’ support of the Deutsche Kinderhilfe Direkt, and this leads into Kollo’s statement about the interpretation of the cycle.

All in all, this recording has much to recommend, not the least of which is the overtly divergent approach that Kollo offers. In a mature, polished singer conveys his well-considered approach to familiar music. Enthusiasts of Lieder and specifically Schubert’s music may find this recording of interest. At the same time, those familiar with Kollo as an opera singer may want to hear him in the context of this fine recording of Schubert’s Winterreise.

James L. Zychowicz

Madison, Wisconsin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/kollo_winterreise.jpg

image_description=Franz Schubert: Winterreise, D. 911

product=yes

product_title=Franz Schubert: Winterreise, D. 911

product_by=René Kollo, tenor, Oliver Pohl, piano.

product_id=Oehms Classics OC 904 [CD]

A Trio of New Year's Concerts

For many years now people have been laughing with the queer and often unintended humorous translations in the interesting issues produced by Bongiovanni; but their records are made on a shoestring budget. La Scala has more means, witness the designer cassette this DVD is wrapped in, but money for good translators still seems to be scarce. The English text of the booklet consequently uses the word “symphony” when an “overture” is meant (sinfonia is either overture or symphony in Italian). The booklet, too, reproduces a photo of the playbill of the evening which clearly proves whose show it is. The name of conductor Riccardo Muti is printed in exactly five times the size Freni and the other singers get. And of course the camera is fixed for lots of time on the face, hands and body language of the conductor; and I cannot say it is a sight I much enjoy. Not that Muti collapses in hysterics or throws tantrums; just that I think he strikes poses. I don’t believe in conductors who in a concert of separate arias, overtures and choruses act as if they have reached another world, even another cosmos where they are deciphering the innermost secrets of the human condition. Looking at Muti who often conducts with his eyes closed reminds me too much of Karajan who introduced this kind of close-up.

Muti was at the height of his powers (as a conductor and theatre boss) when this concert was recorded nine years ago. He is more than ably assisted by orchestra and chorus who play at their best; and La Scala at its best is indeed outstanding. When one hears the chorus singing as if each of its members is a great soloist in its own right and yet blending the sound, one realizes how less exciting and musically strong most other opera choruses are. In this aspect the La Scala Chorus (and probably its orchestra as well) is its own worst enemy as the unions have always been asking for so much money that most gramophone companies preferred cheaper help and we are all the poorer for it.

Muti was at the height of his powers (as a conductor and theatre boss) when this concert was recorded nine years ago. He is more than ably assisted by orchestra and chorus who play at their best; and La Scala at its best is indeed outstanding. When one hears the chorus singing as if each of its members is a great soloist in its own right and yet blending the sound, one realizes how less exciting and musically strong most other opera choruses are. In this aspect the La Scala Chorus (and probably its orchestra as well) is its own worst enemy as the unions have always been asking for so much money that most gramophone companies preferred cheaper help and we are all the poorer for it.

As the title tells this concert is something of a re-enactment of the famous re-opening in 1946 after allied bombs had destroyed the house three years earlier. That concert is now more famous for the legendary discovery of a young new exciting soprano, Renata Tebaldi, than for the return of Toscanini. He placed the soprano who had to sing “voice of heaven” during a rehearsal of the Te Deum at the top of the chorus because “ I want this voice of an angel to truly descend from heaven”. Thus was born the still continuing legend that Toscanini said Tebaldi had the voice of an angel.

Muti, the booklet tells us, gives us the same programme with one exception. He replaced the “La Gazza ladra” by the William Tell overture, no reason is given, though I have an inkling the conductor feels it is a better vehicle for a star of the first magnitude like himself. Anyway it must be admitted that it is a fine and spirited performance. Nevertheless there are far bigger differences with the original concert. Toscanini didn’t give “La vergine degli angeli” from Forza as Muti does and the older conductor had the whole of act 3 of Manon Lescaut performed after the intermezzo from the same opera. That act is deleted here and the ubiquitous intermezzo is followed by one aria, the “In quelle trine morbide” from the second act. This may make this DVD somewhat more interesting as it gives the real star of this evening more to sing. Mirella Freni looks decidedly somewhat old in a not very flattering gown but the 61year old soprano is in fabulous voice singing all soprano parts (in 1946 apart from Tebaldi there was Mafaldo Favero) except those few angel-phrases. There is not a hint of breathiness and the famous silvery sound is there from bottom to top, easily riding the concertato in the Mosé prayer and dominating the Forza scene with chorus and bass. Sam Ramey is a fine Mefistofele in the prologue in a role he always performed well. The wobble that so marred many of his later performances was absent and he cuts a convincing figure as well.

This DVD originally was a TV registration and by now we already know that directors either can read a score or have an assistant next to them who points out which instrument is coming on so that everything runs smoothly without abrupt changes or pointless zooms.

The Venice DVD has somewhat more to look at but my first thought went to the music and I wonder why conductors show so little fantasy in some of these galas. Of course they need not play Alban Berg in a New Years’s Concert but even in those surroundings it could be possible to have something else than once again the Manon Lescaut intermezzo or the “Va pensiero”. The star of the evening is 80+ French conductor Georges Prêtre who even starts the DVD by playing a few phrases from an operetta he wrote 50 years ago. But for the rest, Prêtre seems to be an older Muti; he too looks like he is trying to resolve all human mysteries while conducting arias and intermezzi he has probably conducted hundreds of times and which can be played by the orchestra as well without any conductor at all. At the same time the TV director has no problem giving us a shot of the tenor’s back during most of “Nessun dorma.”

In Europe it has now been a tradition for more than 40 years that on the first of January all public TV-stations broadcast the Vienna Philharmonic New Year’s Concert with mostly Strauss-music. This has slowly become big business and, where for many decades Willy Boskovsky, the orchestra’s Concertmeister, conducted his colleagues, some twenty years ago famous conductors started to kill for the honour and the exposure of conducting this concert (Maazel, Muti, Harnoncourt etc). From simple music making, this show has now become an opportunity to show clips with ballet and Vienna tourist traps while the orchestra plays on. And now the Viennese have some competition from the Venetians who use the same tricks — some shots of the city and three nice and very traditional ballet items mostly danced in the splendid building of the restored La Fenice, while an Asian girl dances on her own with the chorus humming along in the Butterfly “coro a bocca chiusa.” The sung pieces are somewhat rare: a rather provincial “Nessun dorma” by Albanian tenor Gipali and a better Butterfly aria by soprano Annalisa Raspagliosi. And then we go for a half-hour of popular orchestral opera pieces before everything ends with the inevitable “Libiamo” from Traviata. Then the 60 minutes of this concert are over and the happy few who assisted (and are sometimes taking photographs from their boxes) can run to the reception. Probably I’m a little too severe as it is a nice souvenir of the theatre and the orchestra and chorus and the picture quality is excellent.

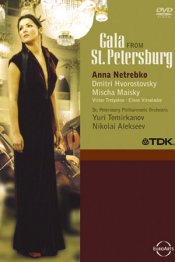

But it is understandable that in a world of clichés the St. Petersburg concerto comes somewhat as a relief. The people in the Philharmonic Hall don’t wear gowns or tuxedos and their dresses, faces and bodies show that most of them do not belong to the jet set. The principal conductor behaves like a normal being, concentrating on his music without pulling strange faces. He lustily applauds with everybody else after a good solo and when he only gets one kiss from Netrebko he almost bows double to get a second one. All the time the sphere is very relaxed and conductor and soloists laugh, make small jokes and amuse themselves and there is less stiffness on the scene than in the clean but sceptic Western concerts. Still there is a lot of good music-making and, though it is not exactly unhackneyed repertoire, it is somewhat refreshing after the Italian perennial favourites. Victor Tretyakov plays a fine Saint-Saëns piece and Elisso Virsaladze proves that her left hand is not her weakest in the Ravel concerto. But it is violoncellist Mischa Maisky who really steals the show with some warm and inspired tone in Respighi and Bruch. And of course there are some singers as well. Anna Netrebko looks far more like a (beautiful) young Russian with less than perfect skin than in the babe-like video registrations from the West. And she wears the same outfit before and after the intermission. The voice is clear, sweet and bell-like and resembles young Mirella Freni a lot, as it is a brilliant lirico with coloratura facility. A pity for us she only sings Italian arias, though maybe her Russian public appreciates this more than we do. I like the small mistake at the end of the first strophe of “quando rapito” as it proves there is no tampering with the recording as some stars nowadays routinely demand in a commercial registration. The voice of Hvorostovsky is becoming more dramatic and voluminous as I noted myself a few years ago in Antwerp. The sound is less youthful but completely homogeneous; and there is a new depth in the lower register so that this fine Onegin has no problems with the bass aria of Prince Gremin. The duet between Silvio and Nedda is passionately sung and acted as well. All in all a nice concert to while away two hours.

But it is understandable that in a world of clichés the St. Petersburg concerto comes somewhat as a relief. The people in the Philharmonic Hall don’t wear gowns or tuxedos and their dresses, faces and bodies show that most of them do not belong to the jet set. The principal conductor behaves like a normal being, concentrating on his music without pulling strange faces. He lustily applauds with everybody else after a good solo and when he only gets one kiss from Netrebko he almost bows double to get a second one. All the time the sphere is very relaxed and conductor and soloists laugh, make small jokes and amuse themselves and there is less stiffness on the scene than in the clean but sceptic Western concerts. Still there is a lot of good music-making and, though it is not exactly unhackneyed repertoire, it is somewhat refreshing after the Italian perennial favourites. Victor Tretyakov plays a fine Saint-Saëns piece and Elisso Virsaladze proves that her left hand is not her weakest in the Ravel concerto. But it is violoncellist Mischa Maisky who really steals the show with some warm and inspired tone in Respighi and Bruch. And of course there are some singers as well. Anna Netrebko looks far more like a (beautiful) young Russian with less than perfect skin than in the babe-like video registrations from the West. And she wears the same outfit before and after the intermission. The voice is clear, sweet and bell-like and resembles young Mirella Freni a lot, as it is a brilliant lirico with coloratura facility. A pity for us she only sings Italian arias, though maybe her Russian public appreciates this more than we do. I like the small mistake at the end of the first strophe of “quando rapito” as it proves there is no tampering with the recording as some stars nowadays routinely demand in a commercial registration. The voice of Hvorostovsky is becoming more dramatic and voluminous as I noted myself a few years ago in Antwerp. The sound is less youthful but completely homogeneous; and there is a new depth in the lower register so that this fine Onegin has no problems with the bass aria of Prince Gremin. The duet between Silvio and Nedda is passionately sung and acted as well. All in all a nice concert to while away two hours.

Jan Neckers

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Dynamic_33482.jpg

image_description=New Years’ Concert 2005 in Venice

product=yes

product_title=(1) New Years’ Concert 2005 in Venice

(2) La Scala 50th Anniversary Concert

(3) Gala from St. Petersburg

product_by=(1) Annalisa Raspagliosi, Giuseppe Gipali, Orchestra e Coro del Teatro La Fenice of Venice, Georges Prêtre (cond.)

(2) Performances by Mirella Freni, Samuel Ramey, Vincenzo La Scola, Elizabeth Norberg-Schulz and Luciana D'Intino. Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala, Riccardo Muti (cond.)

(3) St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, Yuri Temirkanov (cond.) with Anna Netrebko, Dimitri Hvorostovsky, Mischa Maisky, Eliso Virsaladze, Viktor Tretjakov

product_id=(1) Dynamic 33482 [DVD]

(2)La Scala LSB56043 [DVD]

(3) EuroArts 2053408 [DVD]

December 25, 2005

BERLIOZ: La damnation de Faust

First performance: 6 December 1846 at Opéra-Comique, Paris

Principal characters

| Marguerite | Mezzo-soprano |

| Faust | Tenor |

| Méphistophélès | Bass or baritone |

| Brander | Bass |

Synopsis

Part One

Faust, alone on a plain at sunrise, praises the awakening spring day, nature's renewal and his own life in solitude, far from the madding crowd. In a nearby village, merry country people celebrate spring with singing and dancing while an army equipped for battle marches by. Faust withdraws untouched by all.

Part Two

Having returned to his study pensive and unhappy, Faust sinks into profound melancholy and pessimism. Intent on suicide, he is about to drink a cup of poison when from outside he hears the Easter hymn. Faust remembers the purity and piety of his childhood. His faith is reawakened and he reaffirms his commitment to life.

Suddenly Méphistophélès appears and, scorning Faust's sentimentality, suggests that he go out into the world rather than dwell in philosophical speculation. He promises Faust, who is mistrustful at first, to fulfill his most extravagant desires. Faust follows this diabolical companion.

The first stop is Auerbach's Cellar in Leipzig. Faust dislikes the drinkers' raucous singing, Brander's coarse song about the "Rat in the Cellar," and Méphistophélès' cynical reply with his "Song of the Flea." He insists they leave without delay.

Méphistophélès next leads him to the banks of the Elbe and sends him to sleep on a bed of roses. Méphistophélès concocts seductive dreams that beguile Faust, showing him a picture of his mistress-to-be, Marguerite. On awakening, Faust demands to be taken to the girl. Méphistophélès promises to arrange it. He advises Faust to join the soldiers and students going into town and to follow them to Marguerite's house.

Part Three

In Marguerites' room, Faust is filled with a sweet premonition of his romantic adventure. When Marguerite appears, he conceals himself. Marguerite has already seen her lover-to-be in a dream. She sings the ballad of "The King of Thule," in which she gives expression to her longing. As soon as Marguerite has fallen asleep, Méphistophélès appears. His band of beguiling spirits seduce and lead Marguerite to her destruction. With a sarcastic song, Méphistophélès delights in his certain victory.

Faust and Marguerite meet and declare their love for one another. They are interrupted by Méphistophélès who urges Faust to flee as the neighbors have become suspicious and want to warn Marguerite's mother. Méphistophélès assures them that they can meet again the following evening.

Part Four

Marguerite has been jilted by Faust. She longs for his return but senses that he will not come back. The singing of the students and soldiers can be heard from the street below. This makes Marguerite even more conscious of her loneliness.

Meanwhile, Faust finds renewed strength in the midst of nature.

He learns from Méphistophélès that Marguerite is in prison awaiting execution for killing her mother — a crime for which Faust is responsible. Faust implores Méphistophélès to rescue Marguerite. He is prepared to do this on condition that Faust seals their pact with his signature. Faust walks into the trap. They charge off on Méphistophélès' magic horses, but not to Marguerite's dungeon. Instead they descend into the depths of hell amidst earthquakes, thunder, and bloody rain, where diabolical spirits are awaiting their arrival. Faust, dammed until eternity, is thrown into the flames; Méphistophélès is triumphant.

In heaven the angels welcome Marguerite who has been absolved of her sins.

Synopsis courtesy of Los Angeles Opera.

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/mephistopheles_delacroix.jpg

image_description=Méphistophélès dans les airs by Eugène Delacroix, 1828

audio=yes

first_audio_name=Hector Berlioz: La damnation de Faust

first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Damnation_Faust.m3u

product=yes

product_title=Hector Berlioz: La damnation de Faust

product_by=Nicolai Gedda, Marilyn Horne, Roger Soyer, Dimiter Petkov, Orchestra and Chorus of Rome Opera, Georges Prêtre (cond.).

Live performance, Rome, 11 January 1969.

Great News! It's the Dawning of the Atomic Age

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI [NY Times 25 December 2005]

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI [NY Times 25 December 2005]

IT'S easy to fault the major institutions in classical music for being stodgy and averse to risk. Yet music lovers count on the leading opera companies and orchestras to be custodians of the repertory. Take the Metropolitan Opera. Recalling the first half of this season, among many rewarding nights, I'll remember James Levine's buoyant and insightful performance of Mozart's "Così Fan Tutte," with a splendid youngish cast that gave you hope for the future of Mozart singing.

December 24, 2005

Review 2005: opera

Successful productions failed to hide organisational crisis, says Rupert Christiansen

Successful productions failed to hide organisational crisis, says Rupert Christiansen

[Daily Telegraph, 24 December 2005]

Earlier this week, Martin Smith stepped down from his ill-starred chairmanship of English National Opera - a decision greeted with widespread relief in the arts world. Now that he's gone, I can't help dreaming of a wholly new management and leadership for the company, spearheaded by a team of enlightened young musicians and theatre practitioners, supported by some wise old heads skilled in administration and fund-raising.

December 23, 2005

The Year in Music

By Raymond Stults [Moscow Times, 23 December 2005]

By Raymond Stults [Moscow Times, 23 December 2005]

Best Operas: Though Helikon Opera, Novaya Opera and the Pokrovsky Chamber Musical Theater all came up with one new production apiece of more than routine interest and merit this year, it was the Bolshoi Theater that produced the real fireworks of 2005 on the local operatic front.

Soprano Cancels Carnegie Recital Debut

NEW YORK Dec 22, 2005 — Anna Netrebko, the glamorous young Russian soprano, has canceled her debut recital at Carnegie Hall, saying she's not ready to perform a solo concert there.

NEW YORK Dec 22, 2005 — Anna Netrebko, the glamorous young Russian soprano, has canceled her debut recital at Carnegie Hall, saying she's not ready to perform a solo concert there.

The Order in the Chaos of 'Wozzeck'

BY FRED KIRSHNIT [NY Sun, 23 December 2005]

BY FRED KIRSHNIT [NY Sun, 23 December 2005]

Alban Berg realized that he and his mentor Arnold Schonberg were in the process of revolutionizing music, and so, when he came to write "Wozzeck," he clung steadfastly to the late 19th-century Romantic tradition still holding sway in the first quarter of the 20th, incorporating many devices from the most beloved operas. This organization creates grounding for the ear in an otherwise phantasmagoric musical world.

JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU: THE SORCERER OF THE STAGE

By Olivier Rouvière. Translated by Marcia Hadjimarkos [Goldberg No. 28]

By Olivier Rouvière. Translated by Marcia Hadjimarkos [Goldberg No. 28]

Jean-Philippe Rameau’s (1683-1764) first opera was staged when he was fifty years old; his last, written when he was over eighty, was not given until the twentieth-century.

Rameau’s aesthetics are thus characterised by maturity, density, homogeneity, and chronological clarity. His early works were already accomplished to a high degree and his operas occupied the French stage for more than thirty years, only to disappear after his death. To quote Girdlestone’s incisive summing up, Rameau wrote “more than ninety acts of dramatic music” - that is, three acts, or tableaux, a year - during the last third of his life.

December 22, 2005

Tragic Indeed — An American Tragedy is yet another contemporary-opera-by-the-numbers rehash

By Peter G. Davis [New York Magazine, 26 December 2005]

By Peter G. Davis [New York Magazine, 26 December 2005]

The Lit 101 school of American opera continues to proliferate. Little Women, Of Mice and Men, The House of the Seven Gables, Sophie’s Choice, The Last of the Mohicans, The Postman Always Rings Twice, Rappaccini’s Daughter—the list of ambitious operas based on all those classic novels you read in school (or were supposed to) goes on, even if the success rate has been marginal. Right now, the Metropolitan is presenting the world premiere of Tobias Picker’s An American Tragedy, adapted from the 1925 novel by Theodore Dreiser. Not that long ago we were debating the merits of John Harbison’s operatic version of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Can a Met production about a great white whale be far off?

OPERA HOT — The Met’s fall season

by ALEX ROSS [New Yorker, 26 December 2005]

by ALEX ROSS [New Yorker, 26 December 2005]

Joseph Volpe, whose sixteen-year tenure as the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera ends this season, may be remembered as a man who stayed true to his title: he managed. Performances went off with maximum efficiency, seven each week. World-class singers showed up in mostly suitable roles, and if they misbehaved they were shown the door, or at least treated brusquely. James Levine was kept happy. Electronic subtitles appeared on the backs of the seats. Modest efforts were made in the direction of fresh production styles, novel repertory, and premières—Tobias Picker’s “An American Tragedy” bowed this month—but not enough to ruffle anyone’s feather boa. Through various crises—a singer dying onstage, a bloated superstar cancelling, attendance figures falling in the wake of September 11th, a Cuban billionaire patron turning out to be neither a billionaire nor a Cuban—Volpe kept the great old house trundling along. Was he a visionary? No. Did rival American companies—particularly the San Francisco Opera, with its history-making productions of Messiaen’s “Saint Francis” and John Adams’s “Doctor Atomic”—challenge the Met’s preëminence? Yes. But the chaos that has surrounded many big houses elsewhere has been absent from the Met, and in this business the absence of chaos is a considerable achievement.

LUTOSLAWSKI: Twenty Polish Christmas Carols

It is based on the collection of twenty Christmas carols for voice and piano that Lutosławski arranged in 1946, a time when the politics dictated that the arts create works like this for the people. Only someone as steeped in Polish culture as Lutosławski could approach arrangements of these carols with the aplomb that they deserve and, at the same time, introduce elements that do not make them caricatures. The collection is as reminiscent of some of the folksong settings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and the appeal of the music resides in the masterful settings that he gave each piece.

While some of the melodies may be familiar, others are more insular in nature. The carol entitled “Hurrying to Bethlehem” The delicate timbres and floating harmonies of “Lullaby, Jesus” is one of the outstanding selections on this recording. Likewise angular melody of “This is our Lord’s birthday” evokes a Slavic idiom that hints at the kind of choral number a composer like Prokofiev have used in one of his cantatas, while Lutosławski’s orchestration suggests Shostakovich’s style. The wind colors used in “Shepherds, can you tell?” is engaging, especially when they occur with the interplay between solo voice and choral writing. The arrangements by Lutosławski make some wonderful Polish carols available to a broader audience.

This masterful combination of the familiar with a modern touch makes the collection attractive not only as a recording, but also for performances during the Christmas season. The performance preserved on this recording is taken from concerts given on 5 December 2001. In fact, the other pieces on the CD were part of another concert, which was given on 15 January 1997) and include Lutsławski’s Lacrimosa for soprano, choir, and orchestra, as well as his Five Songs for female voice the 30 solo instruments.

The Lacrimosa is one of two settings from the Requiem completed in 1937 by Lutosławski, and as a fragment it offers a glimpse at the composer early in his career. The melody given to the soprano is reminiscent of some of the music Ginastera used in his Bachianas Brasilieras. The overt simplicity that Lutosławski uses in this piece is part of its attraction. As much as it is unmistakably modern, the Lacrimosa is also engaging in its clear presentation of the text, and masterful use of solo voice in contrast to choral passages, all of which are supported by a carefully composed accompaniment. It is unfortunate that the other setting from the Requiem was destroyed and that Lutosławski did not pursue the setting of the entire piece. Those unfamiliar with the work will find this performance to be extremely effective.

Another work that deserves further attention is the set of Five Songs to texts by the contemporary poet Kazmimiera Iłłakowicz (1892-1983). The only nominally secular pieces on this CD, the Five Songs are essentially revisions of children’s verses that have a modern slant, and Lutosławski’s music accentuates that aspect of the texts. Composed in 1957, the Five Songs are a product of a time when Lutosławski benefited from the cultural openness that occurred after Stalin’s regime ended. As with the other pieces collected in this recording, the performance is convincing and conveys the spirit of the music well.

This and the other pieces are performed by the Polish Radio Chorus, Kraców, and the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra (Katowice) conducted by Anoni Wit. The soprano for the set of Twenty Polish Christmas Carols and the Lacrimosa is Olga Pasichnyk, with the alto Jadwiga Rappé serving as soloist for the Five Songs. The diction is clear and serves the texts well, but it is unfortunate that the texts and translations are not provided with the recording. With the exception of Lutosławski’s Five Songs, the texts are available at the Naxos website (www.naxos.com/libretti/20carols.htm), the publication of the materials with the CD makes a difference. At the same time it would also be useful at least to have the titles of the pieces and their components in the original language and also in translation. Nevertheless, this recording makes available some fine music and in turn, it shows yet another side of one of the most important Polish composers of the twentieth century.

James L. Zychowicz

Madison, Wisconsin

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/lutoslawski-Carols.gif

image_description=Witold Lutosławski: Twenty Polish Christmas Carols; Lacrimosa; Five Songs

product=yes

product_title=Witold Lutosławski: Twenty Polish Christmas Carols; Lacrimosa; Five Songs

product_by=Olga Pasichnyk, soprano; Jadwiga Rappé, alto; Polish Radio Chorus, Kraców; Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra (Katowice); Antoni Wit (cond.)

product_id=Naxos CD 8.555994 [CD]

December 21, 2005

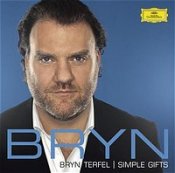

Christmas with Renée and Bryn

She judiciously mixed some of these songs with specific Christmas items and made it a bestselling classical album. Since that time all major singers have recorded recitals of “canti sacri.” Depending upon the number of carols, these were sometimes presented as Christmas albums, though even then there was usually no escaping the two Ave Marias, Louis Niedermeyer’s Pieta Signore, Franck’s Panis Angelicus, Händel’s ode to the shade of a tree and a few Mozart or Bach items — none of which has anything to do with Christmas. Decca’s marketing division and Renée Fleming have decided that it’s better to split these things more rigorously and so together with these “sacred songs” she recorded a “carol album only,” which corresponds with her current concert tour.

Fleming’s repertoire on this CD is almost wholly traditional, while Terfel is more adventurous, though it nevertheless roams along in the same sphere. And there is indeed no escaping Bach/Gounod, César Franck or Amazing Grace on both records. So why did I feel such a marked difference when listening to those two great vocalists? It starts with the title of their albums. I don’t think there is anything sacred to Humperdinck’s Hänsel and a lot of the other items on Fleming’s CD were definitely written by their composers to catch some not very sacred money. Therefore a less pretentious title like “Songs of Faith and Devotion” would maybe have been a better idea. Though “The Lord” and “God” is as much present on Terfel’s CD, his “Simple Gifts” someway makes a more sympathetic impression. Then there are the sleeve photographs: just Terfel looking earnestly into the camera while Fleming is photographed with eyes closed into what looks far more to be an orgasmic moment than a prayer of faith; and I have a feeling that some of the less enthusiastic reactions to Fleming’s CD were initiated by title and photo.

But of course Fleming got a lot of flack on her singing as well. Some comments on those venomous opera-forums spoke of Händel à la Duke Ellington. This is simply not fair as she doesn’t glide or scoop. True, she uses all kinds of allowable vocal tricks like rubato and a good trill, which are arms not all sopranos have. The first impression after her first tracks Ave Maria and Jesus bleibet is one of “how exquisite, how refined” and then first weariness and finally boredom makes its entrance. So what’s wrong in a CD-recital that would not have been boring on 78-records? Well, by the third track one realizes that she is not going to use her full voice and that she will never sing out; that everything will stop at mezza-voce while in that half voice she tries hard to unveil all hidden meanings in each word, if necessary in each syllable by voice inflexions. Moreover as she is nowadays the female star of the label, she suffers from what I’d call Kohnanization, though Domingo and Eugene Kohn are not the only perpetrators. Classical stars nowadays prefer to bring either their own maestros with them or otherwise want to be indulged by the conductor whom they honour by allowing him to have their name as well on their records. So Andreas Delfs nicely follows Fleming but definitely was not engaged to tell her some truths and to bring some vitality to the recording sessions. Once upon a time, Karajan conducted the Price Christmas recital, Gavazzeni led Bergonzi in his début recording and Molinari-Pradelli put the fear of the gods in Sutherland and no singer would have got away with these kind of easy tempi. Levine, Solti, Mackerras, Eschenbach, Tate were the conductors of Fleming’s many successful earlier recordings; and in retrospect one realizes that they were sympathetic to the artist without sapping all rhythmic liveliness from the CD, indulging every whim of the singer (and you didn’t need a looking glass to find their names on the sleeve).

That too is one of the differences with the Terfel recording. Barry Wordsworth may not be a big name either as a conductor but he doesn’t linger on and at least gets his photograph in the booklet (or Terfel himself has a far better sense of tempi). Not that everything is perfect in this record as it shows some serious vocal problems. The bass-baritone who came in second after Dmitry Hvorostovsky in the Cardiff competition in 1989 has made some far fetching decisions. Though the voice has the tessitura of a real bass-baritone (I heard him do a fine Dulcamara in Amsterdam a few years ago), Terfel was blessed with good top notes and he couldn’t keep his hands off real baritone territory. His Amsterdam outing as Scarpia was not really a success. Moreover he has now stepped into heavy Wagner with some successes in Rheingold and Walküre but recently he withdrew as Wanderer in Siegfried. The low and middle register are still very beautiful but the voice really makes a clearly unmusical jump which sometimes almost becomes a shout to reach an F; and, as he does it several times on this record, it is clear he has somewhat damaged his vocal means.

Terfel doesn’t have Fleming’s intrinsic beauty of voice, indeed his timbre is somewhat indistinct, but his sense of phrasing and words is far greater. His Sondheim-song is particularly impressive. He too sings a lot in warm toned pianissimo but realizes that parts of some songs demand full voice. And then there is the repertoire: maybe not very adventurous but still known to most opera buffs who collect drawing room songs and ballads by Crooks, Kullmann and friends; and one can easily savour Terfel’s fine English pronunciation without his losing the vocal line. The CD offers us two duets with baritone-colleague, Simon Keenlyside, who clearly makes a bigger noise than Terfel (on record at least), though the voice has nothing of the beauty and the subtlety of the Welsh singer. Clearly I could easily have done without his part; but it is a nice reminder that Terfel, notwithstanding some vocal problems, is still a great artist.

Jan Neckers

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/Fleming_Sacred_Songs.jpg

image_description=Renée Fleming: Sacred Songs

product=yes

product_title=(1)Renée Fleming: Sacred Songs

(2)Bryn Terfel: Simple Gifts

product_by=(1)Renée Fleming, with Susan Graham and Mark O’Connor, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Andreas Delfs (cond.).

(2) Bryn Terfel, with Simon Keenlyside, John Williams and Aled Jones, London Symphony Orchestra, Barry Wordsworth (cond.).

product_id=(1) Decca 475 7177 (US and Australia); 475 6925 (Int'l) [CD]

(2) DG 477 5563 (Int'l) 4775919 (UK)

RACHMANINOV: The Miserly Knight

Each of these productions has been released separately on DVD; though the operas themselves are less than 70 minutes long, each DVD also features bonus material, including interviews with conductor, director, and stars. Even at less than full price, the 95-minute long The Miserly Knight DVD may not seem like a bargain, but for an outstanding performance of a rare repertory piece, it offers good value indeed.

In the first of three short scenes, all apparently only slightly adapted from the original source material by Rachmaninov, we meet a young knight plagued by debts. A moneylender suggests that he arrange for the murder of his father, a baron (the eponymous character) who hoards his fortune and keeps his profligate son on a tight budget. The young knight refuses, and decides to protest his case to the Duke. The second scene, a long dramatic monologue for the father, has no action whatsoever. Then, in the confrontation before the Duke, the father accuses the son of desiring his death. The son denies it (and is carted away by the Duke’s men in this production), and then the father collapses and dies.

Not exactly a narrative arc of Puccinian drama and characterization. Undoubtedly the challenges of staging the work have contributed to its neglect. Rachmaninov would go on to write one more one-act opera, Francesca di Rimini, and along with the earlier Aleko, all three works reflect his mastery of orchestral texture and drama, and give some evidence of his melodic genius. And yet none really quite makes a case for itself as a total success. Recordings led by Neeme Jarvi of all three have recently been released on the DG “Trio’ series, and they make for fascinating listening.

But seeing The Miserly Knight in this Glyndebourne production, directed by Annabel Arden, makes one wish more opera companies would search out interesting one-act operas to be paired with the more successful ones, as Glyndebourne did by presenting the Rachmaninov with Puccini’s classic. Director Arden has fully bought into the tormented drama of Rachmaninov’s score, and the dark, monochromatic sets effectively partner the excellent acting of the cast.

Arden’s riskiest move, and a brilliant success, involves an "aerialist” (Matilda Leyser), who dangles from ropes and clambers around the multi-level sets. An androgynous figure, with the skin and hair of an old man but the youthful, impish face of a youth, this figure appears briefly at the start and then throughout scene two, managing to enhance the long monologue, so brilliantly delivered by Leiferkus, without distracting from the focus on the knight. A booklet explaining the links between the two productions describes the aerialist as “the spirit of greed, the Baron’s conscience and death itself…” One can experience this supernatural figure on that level, or one can simply revel in the eerie effect created by Leyser’s amazing physical dexterity and truly astounding facial expressions.

Richard Berkeley-Steele, a fairly good Siegmund in the recent Barcelona Ring DVD set, does even better here, sounding comfortable with both the language and tessitura of the role. As the Duke, Albert Schagidullin creates a character in a few short lines, a self-satisfied, cold-hearted ruler who adopts a pose of fairness to cover his own avaricious nature (Arden has him claiming the Baron’s wealth after his death). Viacheslav Voynarovskiy sings with appropriate unctuousness as the Moneylender, a role that in the unexpurgated original apparently veers into anti-Semitic characterization (this according to a recent Gramophone review of a Chandos recording of the opera). Here, he is just one more loathsome figure in a misanthrope’s daydream…or nightmare.

Vladimir Jurowski, clearly relishing both the score and his own youthful, handsome self (those tresses are something else), leads the LPO in a riveting performance.

Glyndebourne by reputation is seldom an easy ticket to acquire, even if one happens to be taking the summer in the UK. To have a new production from last year available on DVD is wonderful in itself, and when it is the quality of this particular one, then generosity can be said to be at the heart of this Miserly Knight.

Chris Mullins

Los Angeles Unified School District, Secondary Literacy

image=http://www.operatoday.com/content/miserly_knight.jpg

image_description=Sergei Rachmaninov: The Miserly Knight

product=yes

product_title=Sergei Rachmaninov: The Miserly Knight