June 30, 2015

Guillaume Tell, Covent Garden

Which is a shame for on the first night there much fine singing, strong musical direction from Antonio Pappano in the pit, and a convincing central trope. But, there was also a wealth of redundant stage business and an absence of meaningful stagecraft, with a series of tableaux replacing genuine dramatic development. And, then there is the director’s decision to foreground the sexual brutality of war, which so many in the audience — myself included — found sensationalist, distasteful and gratuitous.

Paolo Fantin’s plain white-cube set, with its soil-strewn sloping floor, evokes recent Balkan conflicts, though the context is widened by the costumes of Carla Teti which range from the 1940s to the present day. There is certainly nothing very pastoral about the opening Shepherd’s Festival — even though Michieletto repeatedly hammers home the need to connect with the spirit of one’s homeland as embodied in its earth. The villagers’ weddings celebrations are rather muted as they sit at bare tables, the dull brown alleviated by just a single unexceptional tree.

Sofia Fomina as Jemmy, Enkelejda Shkosa as Hedwige, and Eric Halfvarson as Melcthal

Sofia Fomina as Jemmy, Enkelejda Shkosa as Hedwige, and Eric Halfvarson as Melcthal

But, this tree is Michelietto’s big idea. Uprooted at the end of Act 1 by a marauding Austrian soldier, the tree returns to dominate the stage in the subsequent acts: horizontal and enlarged, its twisting branches and gnarled roots etch and score sharp gothic shadows onto the bare skies beyond. It is a striking symbol of the threat posed by colonial terrorists to a land and its people, but Alessandro Carletti’s lighting design is fairly unadventurous — a few juxtapositions of yellow and blue but otherwise muted — and over the succeeding three and a half hours the shadows blend into the prevailing greys and browns. More problematic is the fact that the tree is a hindrance to movement; so, the fallen trunk can revolve to reveal different locations but there is little meaningful choreography within those locations.

Perhaps we are supposed to imagine the various scenes as a sequence of story-book stills? For, as is made clear to us by the film projection which accompanies the overture, what we are witnessing is actually taking place in the imagination of William Tell’s son, Jemmy. This also helps to explain how and why the silent Robin Hood-figure who roams the stage, flamboyantly stabbed arrow-heads and later a shining cutlass into the table tops and soil, has found himself amid these rather bland mid-twentieth century insurgents. Thus, this feather-hatted, red-cloaked archer has stepped straight from the Illustrated Classics tale that Jemmy has been reading while manoeuvring his lime green and mustard yellow toy soldiers into strategic battle formations. And, the legendary medieval marksman provides a benchmark by which young Jemmy can measure his own father’s achievements and courage, culminating — when Tell has been captured — in a petulant outburst in which Jemmy rips the pages from his book, while the comic-strip narrative is projected on a front-stage screen.

Nicolas Courjal as Gesler

Nicolas Courjal as Gesler

The red-cloaked figure comes into his own in the mimed scenes with which Michelietto replaces Rossini’s original dance sequences. In 1820s Paris, Rossini’s Opéra audience welcomed, indeed expected, lengthy ballet scenes; but the diegetic dance music presents a challenge for the modern director. In this production, the divertissement of Act 1 is an archery competition in which Jemmy finesses his skills, but even the presence of the master-archer cannot stop a few of the arrows falling shy of the bull’s-eye. And, such child’s-play is not entirely harmless, Michieletto suggests, when in Act 2 the Austrian soldiers try to teach the Swiss children how to a cross a sword or pull a trigger — not so dissimilar to the lesson in weaponry that Tell gives his son.

There’s a lot of superfluous business in these mime episodes, but they trundle along without causing undue alarm, until we reach Act 3. Now, the forest floor is decorated with, first, the genteel soft furnishings of Mathilde’s Habsburg palace, and then the elongated table and sparkling chandelier of the occupying Austrian officers’ banqueting room. The sadistic Austrian Governor, Gesler, orders festivities to mark the Empire’s benign sustenance of the pitiful Swiss nation; one would expect some innocuous folky stuff to follow. But, Michieletto gives us a prolonged sexual attack during which a female actor is abused by the officers, force-fed champagne, molested with a pistol and then stripped naked and gang-raped atop the banquet table.

These unwarranted, distasteful antics are not only entirely completely at odds with the spirit and style of Rossini’s music, but on this opening night they also upset a large proportion of the audience who proceeded to make their condemnation piercingly known; and as the jeering and hissing escalated, the hecklers were themselves barracked by those disapproving of such mid-performance raucousness. Pappano and the cast ploughed on regardless, only to be greeted with more hooting at the end of the dance sequence.

Cat-calling at the curtain has been common of late at Covent Garden but, clearly rattled by such an unprecedented mid-performance outburst, Kasper Holten subsequently felt obliged to issue an explanatory, mollifying statement: ‘The production includes a scene which puts the spotlight on the brutal reality of women being abused during war time, and sexual violence being a tragic fact of war. The production intends to make it an uncomfortable scene, just as there are several upsetting and violent scenes in Rossini’s score. We are sorry if some people have found this distressing.’

Malin Byström as Mathilde

Malin Byström as Mathilde

In truth, the sexual violence was probably no more explicit than that presented in any number of modern opera, theatre or cinema productions; but, it was prolonged and uncalled-for. Few can be unaware of the ‘brutality, the suffering [people in war zones] have had to face’ (which Michieletto has insisted it was his intent to illuminate for us) given the newsfeed from war-torn lands which we see on a daily basis. But, the heckling was excessive too, and it made it difficult for Pappano and the cast to establish a fittingly poignant mood for the beautiful duet between Guillaume and Jemmy which follows, as the former prepares for his apple-target challenge.

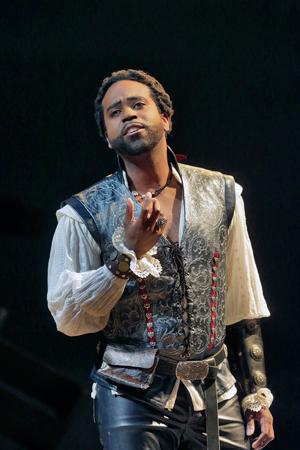

The sneering of a few malcontents threatened to resume at the start of Act 4, just as John Osborn prepared to tackle one of the most demanding scenas in the opera, indeed in the repertoire, but it was silenced by the hushings of the majority. In the role of Arnold Melcthal, Osborn gave the performance of the evening, surmounting the registral challenges with confidence and security. Arnold was understandably tense in Act 1, and he tended to launch vigorously at the top notes, sometimes over-reaching and the tone a little taut. But, he relaxed into the role — his Act 2 duet with Mathilde, ‘Oui, vous l'arrachez à mon âme’ (Yes, you wring from my soul) was beautifully phrased — and he showed great stamina, going from strength to strength as the drama unrolled. Osborn has both the dark weight and bel canto lyricism that the role demands, and he exhibited flexibility, bright clarity and superb enunciation in the stirring lament that opens Act 4, and tremendous power and projection in ‘Amis, amis, secondez ma vengeance’ (Friends, friends, assist my vengeance) despatching the repeating top Cs with dramatic and musical conviction.

Malin Byström was clear-voiced as Mathilde, using varying tone to convey emotion and passion. She and the other soloists were not always sympathetically supported by Michieletto: at the start of her first aria — ‘Sombre forêt, désert triste et sauvage’ (Somber forest, sad and savage wilderness) in Act 2 — Byström was asked to climb onto the twisted tree trunk at a time when she must have had other, more important, musical matters to contemplate than focusing on not slipping from her precarious platform. It was also unclear why she needed to take off some of her clothes during this aria — surely it was cold in the forest — unless it was to embrace the tree with her bare flesh in order to imbibe the spirit of her fatherland?

Gerard Finley’s William Tell is a rather dejected and jaded people’s champion, seemingly worn out by the struggle both to resist his oppressors and to inspire his countrymen. But, while at times dramatic low-key, Finley was a characteristically dignified musical presence; each phrase was carefully considered and his legato phrasing and even tone production gave Tell stature and won our compassion. His anguished guidance to Jemmy, ‘Sois immobile’ (Stay completely still), before his young son must face his father’s cross-bow, was deeply moving. And, Finley was a striking figure at the end of Act 2 as, stripped to the waist and smeared with the blood and earth of the Swiss brotherhood, he raised his fist aloft, urging his fellowmen to revolution.

John Osborn as Arnold Melcthal

John Osborn as Arnold Melcthal

If Tell was rather world-weary at times, his son Jemmy bounced about in his knee-length trousers like a boisterous Hansel who’d strayed into the wrong opera. Sofia Fomina sang with fresh sweetness, but her caricature Jemmy was out of kilter with the general tone.

There were strong performances from the supporting cast. Enkelejda Shkosa was a convincing Hedwige, Tell’s wife; in the Act 4 trio in which she is reunited with her son, and in her premature aria of mourning for the husband she fears is dead, ‘Sauve Guillaume! Il meurt victime de son amour pour son pays’ (Save William! He died a victim of his love for his country), the Albanian mezzo-soprano showed that she is a genuine singing actress. Jette Parker Young Artist Samuel Dale Johnson was a confident, smooth-toned Leuthold and Michael Colvin’s rich lyrical tenor evoked the sinister cruelty of Rodolphe, Gelser’s commander. Nicolas Courjal’s Gesler is vivid, though perhaps a shade too close to becoming a comic-book sadist; but Courjal used the words and his black-hued bass effectively. Ruodi’s harp-accompanied fisherman’s song was delivered with a gentle lilt by Mikeldi Atxalandabaso, and Eric Halfvarson’s Malcthal senior had strong presence, once he’d got his rather wayward vibrato under control.

Given the dearth of dramatic drive on stage, Pappano worked hard to maintain the musical momentum. The overture was somewhat disappointing: the five solo cellos’ ‘Dawn Prelude’ was a little tentative and the trombones’ running scales in the Storm lagged behind the beat. But, things settled down and Pappano exploited Rossini’s emotive textures and colourings to the full. The horns, particularly, were on terrific form all night — heartily bombastic in the Act 2 huntsmen’s chorus — and there was finely nuanced playing from the woodwind complemented by accurate rapid passagework in the strings.

Rossini relies heavily on the chorus in this opera, but the Royal Opera Chorus gave an inconsistent performance. At their best — when the men of the three Swiss cantons swear to fight or die for the freedom of Switzerland at the close of Act 2 (when they were illuminated by the blinding gleam of revolutionary fervour), or in the triumphal choruses of Act 3 — they sang with vigour and heartiness; but the Act 1 choruses of young people and villagers were pretty lacklustre, and the chorus were persistently adrift of Pappano’s beat; almost irretrievably so in Act 4. It was perhaps not entirely the chorus’s fault that they failed to make a more dependable impact. Given that the stage was dominated by the fallen tree, there was barely room for them to stand, let alone move; and it was not clear why Michieletto thought that asking the down-at-heel Swiss rebels to remove their shirts, revealing their greying old vests, would enhance their image as valiant revolutionaries.

There is nothing very epic, heroic or spectacular about this Guillaume Tell. Michieletto misses the target by a mile, though the final image perhaps offers some consolation. The chorus sift through the soil rejoicing at the resurgence of their homeland and as the toppled tree is raised aloft, a young boy comes to the fore-stage and, in a bright spotlight, plants the sprigs of a sapling: the roots of a culture can never be entirely expunged. One must hope that the same is true for Covent Garden itself: that, as it continues in good musical health, new directorial roots will forge down into the achievements of the past and revived shoots will emerge.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Guillaume Tell: Gerald Finley, Arnold Melcthal: John Osborn, Mathilde: Malin Byström, Walter Furst: Alexander Vinogradov, Jemmy: Sofia Fomina, Hedwige: Enkelejda Shkosa , Gesler: Nicolas Courjal, Melcthal:Eric Halfvarson, Rodolphe:Michael Colvin, Leuthold: Samuel Dale Johnson, Ruodi: Enea Scala , Huntsman: Michael Lessiter; Director: Damiano Michieletto, Conductor:Antonio Pappano, Set designs: Paolo Fantin, Costume designs: Carla Teti, Lighting design: Alessandro Carletti, Royal Opera Chorus, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, Monday 29th June 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/150623_1096-tell-2-adj-GERALD-FINLEY-AS-GUILLAUME-TELL-%28C%29-ROH.-PHOTOGRAPHER-CLIVE-BARDA.png image_description=Gerald Finley as Guillaume Tell [Photo: ROH / Clive Barda] product=yes product_title=Guillaume Tell, Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Gerald Finley as Guillaume TellPhotos: ROH / Clive Barda

Sara Gartland Takes on Jenůfa

A few weeks ago, when I spoke with her by phone, she told me her story and why she thought she was ready to add this new role.

MN: Where did you grow up?

SG: I was born and grew up in a suburb of St. Paul, Minnesota. Both my mom and dad are from there. Even now, I’m the only one in the family who no longer lives in that area, although my parents spend winters in Florida. They come back for the summers, which, unfortunately, are no longer what they used to be. Now it rains more and does not get warm until August. We are lucky if we get one good week before the leaves begin to turn.

Sara Gartland [Photo by Marysol Flores]

Sara Gartland [Photo by Marysol Flores]

MN: Did you study piano?

SG: Yes, my mom had me take piano as a child and although I can’t play well enough to accompany myself, I can play chords and my vocal line. That was very helpful in college because I had to pass piano proficiency tests for both my bachelor and master’s degrees. I started voice lessons the summer before I entered high school. At that time I was participating in so many activities that my mom let me drop piano. Now I wish I had kept up those lessons because I would like to be better able to accompany myself.

MN: When did you see your first opera?

SG: I saw Bizet’s Carmen at Minnesota Opera when I was a senior in high school. I don’t remember the cast but I loved the dramatic staging. The action and music made a big impact on me. I still love Carmen. It has everything in it.

MN: Where did you go after high school?

SG: I did my undergrad work at the University of Wisconsin at Madison and my master’s degree at the University of Colorado at Boulder (CU). In 2004, when I had just finished my master’s, CU implemented an opera certificate degree. They accepted me into their program and I became the first official recipient of CU’s Professional Certificate in Opera and Solo Vocal Performance. For me it was a fine opportunity because I needed time to marinate and learn more about my voice. Eventually, I went on to become an Adler Fellow at San Francisco opera. The opera certificate program at CU was very helpful to me because I worked on refining my languages and learned many roles there.

A scene from La bohème at San Diego Opera [Photo by Ken Howard]

A scene from La bohème at San Diego Opera [Photo by Ken Howard]

MN: What did you learn from your teachers that you would like to pass on to the next generation of singers?

SG: My current teacher, Anthony Manoli, talks about a suppressed yawn and deep, low, connected breath. My first teacher, Ilona Kombrink, taught this way as well. These concepts are fundamental to singing. Understanding breathing is of maximum importance. Singing should be as natural to a singer as crying is to a baby. Breathing for singing really is that simple. Babies don’t worry about being heard . . . and they most certainly are heard.

MN: How finished an artist should a young singer be when leaving school?

SG: Young singers need to know what they want from this career, and whom they trust with their instrument. The teacher is everything. Opera companies and Young Artist programs want to be able to plug them into existing holes in their programs. Most expect their young artists to be ready to perform onstage.

A scene from Roméo et Juliette at Des Moines Metro Opera

A scene from Roméo et Juliette at Des Moines Metro Opera

MN: Did you sing at Irene Dalis’s Opera San Jose?

SG: I did. I was most fortunate in the opportunities that were available to me. When I had completed the Adler program at San Francisco Opera (SFO), Maestro Joseph Marcheso who works at both SFO and at Opera San Jose, asked if I would be interested in singing Gretel in Hansel and Gretel. He had heard me when I was a cover in the SFO Nixon in China because he was the cover conductor for that production. I had already sung Gretel in German in college. Opera San Jose was presenting it in English and I relished the fact that I would learn it in my own language. The program at San Jose is fantastic and I loved my time there.

MN: Do you sometimes say no to a role because you don’t think it suits your voice?

SG: Not so far. Jenůfa, which I will be singing in July at Des Moines Metro Opera, is a change for me, but I don’t find it to be a problem. The music is incredible, and the Czech language feels so good to sing. It is really an Italianate language. Janáček wrote these beautiful verismo-like passages with dense orchestration. It is everything a singer wants in a role. The production, led by director Kristine McIntyre and conductor David Neely, is truly epic. They pay every possible attention to detail and drama. The cast, which includes Brenda Harris, Richard Cox, Joseph Dennis, and Joyce Castle, is phenomenal. It is going to be a real ride for the audiences at Des Moines Metro Opera this season.

MN: What is your interpretation of the title role?

SG: When approaching a role like this, I always focus on the language first. Speaking the Czech text and translating it helps the meaning and emotion sink in. Then I listen to every single recording I can find. Once I begin to learn the music, I take it to my teacher, Anthony Manoli, in New York City. He knows my voice and temperament, and he helps to mold and guide my vocal journey through every new character. A strong solid vocal technique is the key. With Tony’s technique and ears, I’m able to use my voice to communicate the composer’s musical intention without compromising my vocal integrity.

Click here for information regarding Des Moines Metro Opera’s production of Leoš Janáček’s Jenůfa

Click here for information regarding Des Moines Metro Opera’s production of Leoš Janáček’s Jenůfa

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Gartland_01.png

image_description=Sara Gartland [Photo by Marysol Flores]

product=yes

product_title=Sara Gartland Takes on the Dramatic Role of Jenůfa

product_by=An interview by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Sara Gartland [Photo by Marysol Flores]

June 26, 2015

Aida, Opera Holland Park

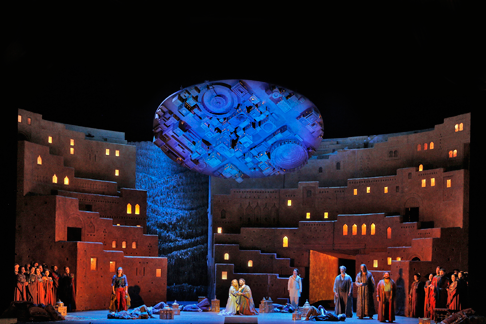

But the wonderfully taut plot, tensions between public duty and private desire, strongly drawn characters and challenging music can provide a highly satisfying experience, especially as the leading roles are some of the most challenging and rewarding in the repertoire. Opera Holland Park has a track record for daring, producing operas which stretch the limited technical resources of their stage, so it was with great interest that I went along to the company’s very first production of Aida, which debuted on 24 June 2015. Daniel Slater directed, with designs by Robert Innes Hopkins and lighting by Tim Mascall, with Gweneth-Ann Jeffers as Aida, Peter Auty as Radames, Heather Shipp as Amneris, plus Graeme Broadbent as Ramfis, Jonathan Veira as Amonasro, Keel Watson as the King and Emily Blanch as a priestess. Manlio Benzi conducted the City of London Sinfonia.

Inevitably we could not expect pyramids, camels and large scale theatrical effects. But Daniel Slater’s production was certainly not without surprises. The basic set consisted of a museum-like using the Holland Park House façade as backdrop and with statues from Ancient Egypt in a museum display. During the prelude, the chorus in modern dress (dinner suits and long dresses) exploded onto the stage and the opening scene was a party. Clearly we were in a modern Kingdom, albeit one obsessed by the past as Radames was inducted as general by dressing him in Ancient Egyptian garb, and for much of the second half the populace were dressed in neo-Ancient Egyptian fancy dress. Aida was a cleaning lady, busy cleaning up after the party-goers. The production was secularised, with Ramfis becoming a rather nasty political fixer. But the production had more surprises for us, when the captured Ethiopians are brought on in a small huddle they were dressed as service workers - cleaning ladies, janitors etc. Were they real Ethiopian captives who had been dressed like that to demonstrate that they were unimportant, or was the war on invading ‘Ethiopians’ really a border war with illegal immigrants? It was never made clear, but I inclined to the latter. Whichever, the Egyptians were displayed as rather nasty, selfish and unsympathetic.

Heather Shipp as Amneris and Peter Auty as Radames

Heather Shipp as Amneris and Peter Auty as Radames

But the removal religion from the plot, and the modernisation of the milieu also removed an essential element from the plot, the tension between public duty and private desires. In Daniel Slater's production I was not clear what Radames meant when he says he is renouncing his duty to his country, certainly he seemed to be emptying his wallet? The end result was gripping theatre, but it wasn't quite the Aida that Verdi envisaged.

When staging the opera the biggest question is not where to set it, after all Verdi’s plot works in a whole variety of situations, but what to do with the triumph scene. Aida came between the grand French version of Don Carlos and the first Italian version of that opera, Don Carlo. In Aida, with its combination of intimate scenes, and a conflict between public duty and private emotional desires in the context of a grand historical narrative, Verdi would seem to have been interested in re-working the French grand opera form to suit the Italian stage. This means that the triumph scene functions very like some of the large scale historical scenes with ballets in French grand opera. Wherever you set it, it needs large forces to bring it off, and frankly a lot of the music is not top-notch Verdi. A logical step would seem to be to cut it, but no-one does. Daniel Slater and movement director Maxine Braham gave us an orgy like party scene in which the Egyptians seemed to over indulge in everything in celebration of their ‘triumph’ over the Ethiopians. It made dramatic sense, and the chorus was clearly having fun, but the scene went on far too long, yet it was clearly appreciated by most of the audience.

The production worked because Opera Holland Park had assembled a strong and balance team of soloists under conductor Manlio Benzi. Whatever you thought of the ideas behind the production, the musical values were very high indeed and Daniel Slater had drawn vibrant performances from all concerned.

Aida is rather a passive role, and one of Gweneth Ann Jeffers (many) strengths was that even before she sang a note she had conveyed much of the character’s interior life. Throughout the opera her face, eyes and body language were profoundly expressive and gave us real insight into Aida’s mental stress. Gweneth Ann Jeffers has a substantial, vibrant voice (previously she has sung La Gioconda, Leonora in La forza del destino and Santuzza at Opera Holland Park and she has performed Aida at a number of theatres including Finish National Opera), yet she was also able to spin a beautiful long line. The Nile scene was sung with real expressive finesse with some finely extended quiet high notes. Throughout there was this sense of line, combined with a vibrant, well filled feeling for Verdi’s phrasing. She and Peter Auty’s Radames developed a really intense relationship, again using eyes and body language well before they sang a note together. Both brought out the secure core of the underlying relationship, the ending was never in doubt. The final scene gave us some finely sinuous lines in Verdi’s glorious melodies, though Daniel Slater did not help matters here by making both of them fatally ill and having the scene performed crawling about the floor. This was one area where I felt that less would have been more.

Graeme Broadbent as Ramfis and Peter Auty as Radames

Graeme Broadbent as Ramfis and Peter Auty as Radames

If I said that Peter Auty’s Radames was a good steady portrayal of the hero, making him solid and dependable, then though sounds unexciting then it must be set into context of a role which few tenors today can sing with any degree of credit. Peter Auty gave a robust account of Celeste Aida with a climax which was secure, and expressive even if a trifle louder than ideal. But once past this hurdle he developed in strength, intensity and a feeling of the heroic, this was no stand and deliver performance.

Heather Shipp was a powerful Amneris, combining a vibrant vocal performance with a highly musical personality. She was very much an Amneris who chewed the scenery, but did so with a musical sense too. The Act 2 scene with Aida, where Amneris tricks Aida into revealing she loves Radames, was particularly strong with the two singers making a balance pairing. And Heather Shipp’s performance revealed what we already knew, Amneris was a complete bitch goddess - attractive, powerful, power-dressed and vicious. Her wonderful final solo scene was superbly done, Heather Shipp really held the stage with her strong, vibrant voice and intense dramatic presence, but the effect was weakened by making Peter Auty’s Radames run around, fleeing from the priests. Another example of the feeling that Daniel Slater was over-egging the drama.

Jonathan Veira made highly sympathetic Amonasro, bringing intensity to the role but he seemed to want to punch each note out so that his performance though vibrant rather lost any sense of line. He and Gweneth-Ann Jeffers poignantly brought out the tension in their relationship.

Graeme Broadbent's Ramfis was a far stronger personality, far more involved in the drama than is sometimes the case and he turned in a wonderfully vivid, at times alarming portrayal of a nasty piece of work. Keel Watson brought his large voice to bear on the King to create a really larger than life musical personality.

Emily Blanch made a fine impression in the small role of the priestess, now reduced simply to a cabaret vamp, and Peter Davoren was the messenger in Act One.

The chorus (chorus master Nicholas Jenkins), with no extra dancers involved in the production, were hard working and delivered a really strong musical performance throughout, singing with strong, vividly focussed tone. Whilst I might have had doubts about the staging of the Triumph scene, the quality of the musical and dramatic performance from the chorus was never in doubt. In the men only sections of the opera, the male chorus made a fine, firm sound and had a nice line in threatening behaviour. The women were seductive in the extreme in their scenes.

I was slightly worried about balance at first, as Manlio Benzi seemed to encouraging a strong and colourful account of the score from the orchestra but this settled down after a while and we were able to sit back and enjoy a vibrantly dramatic account of the score.

Robert Hugill

Cast and production information:

Aida: Gweneth-Ann Jeffers, Radames: Peter Auty, Amneris: Heather Shipp, Ramfis: Graeme Broadbent, Amonasro: Jonathan Veira, the King: Keel Watson, priestess: Emily Blanch, messenger: Peter Davoren Conductor: Manlio Benzi with the City of London Sinfonia. Director: Daniel Slater, Designer: Robert Innes Hopkins, Lighting: Tim Mascall. Opera Holland Park, 24th June 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/aida-ohp-054---Gweneth-Ann-Jeffers.png image_description=Gweneth-Ann Jeffers as Aida [Photo by Robert Workman] product=yes product_title=Aida, Opera Holland Park product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: Gweneth-Ann Jeffers as AidaPhotos by Robert Workman

Welsh National Opera explores Madness for autumn season

Madness descends upon Welsh National Opera for its autumn 2015 season, with three new productions that will explore human turmoil through some of the finest musical expressions of madness and the human condition.

The season launches WNO’s 70th birthday year which will see the company stage seven new productions over the course of the year — including two world premières — and a classic revival.

Press Release: Welsh National Opera explores Madness for autumn season

The season launches WNO’s 70th birthday year which will see the company stage seven new productions over the course of the year — including two world premières — and a classic revival.

Opening the autumn season is a new production of Bellini’s I puritani; the composer’s final opera and widely regarded as a bel canto masterpiece. Following the season theme, the heroine Elvira’s descent into madness inspired Bellini to create one of the most exquisitely refined musical portraits of insanity in opera.

I puritani will be directed by former WNO staff director Annilese Miskimmon, Artistic Director of Den Jyske Opera/Danish National Opera who are also co-producers. Following critical acclaim for both William Tell and Moses in Egypt with WNO, Carlo Rizzi returns to conduct I puritani, and celebrated bel canto tenor Barry Banks returns to sing Arturo. Rising Italian lyric soprano Rosa Feola will sing Elvira in Cardiff, Southampton and Bristol, with Linda Richardson singing the role for the remainder of WNO’s UK tour. David Kempster will sing Riccardo Forth and Wojtek Gierlach, Giorgio.

One of Handel’s greatest operas — Orlando — comes to WNO in a production that originated at Scottish Opera in 2011. It provides a fascinating insight into musical virtuosity as a metaphor for insanity as Orlando’s vertiginous descent into madness at the end of Act II is sublimely depicted through Handel’s music, balancing his inner suffering with fevered anguish to immense effect. Directed by Harry Fehr, Orlando will be set in 1940s London during World War II, providing a fitting backdrop to heighten the emotional impact of the story against the devastation of the Blitz.

Baroque virtuoso, Rinaldo Alessandrini will conduct the impressive cast which includes international countertenor Lawrence Zazzo in the lead role; his debut performance as Orlando. WNO welcomes back internationally-acclaimed Welsh soprano Rebecca Evans to sing Angelica. Fflur Wyn also returns to WNO following her performance in Autumn 2014’s William Tell to sing Dorinda. Robin Blaze and Daniel Grice will sing Medoro and Zoroastro.

The season is completed with Sondheim’s musical masterpiece, Sweeney Todd, which explores not only the madness of the protagonist but of society as a whole. This production promises a musical with all the emotional impact of opera and will be a rare opportunity to hear Sweeney Todd with the celebrated WNO Chorus and Orchestra. This production is set in the late 1970s/early 1980s and provides a fresh take on the story with echoes of Thatcher’s Britain.

A co-production between Welsh National Opera, Wales Millennium Centre and West Yorkshire Playhouse in association with Royal Exchange Theatre, Sweeney Todd will be directed by WYP Artistic Director James Brining and conducted by James Holmes in a staging adapted for WNO. This is the first time that WNO and Wales Millennium Centre have worked together as co-producers, and there will be an extra run of the production presented with Wales Millennium Centre following WNO’s autumn UK tour.

The cast will feature opera and musical theatre singers with German baritone David Arnsperger as Sweeney Todd and Scottish soprano Janis Kelly as Mrs Lovett. Anthony will be sung by Jamie Muscato, with Soraya Mafi singing Johanna. Welsh tenor Aled Hall will sing Beadle Bamford and Charlotte Page will sing Beggar Woman. Also joining the cast are Steven Page as Judge Turpin and George Ure as Tobias Ragg.

During the autumn season, WNO will be working with primary schools in Cardiff, Bristol, Oxford and Birmingham on The Sweeney Adventures. 330 pupils in total across the four cities will take place in workshops where they will use music and drama to explore the hardships faced in Victorian Britain for themselves; a key aspect of the KS2 history curriculum. The project is the third in a series of interactive adventures and follows on from the Tudors — Killing Cousins project in 2013 and My Perfect World in 2014.

Commenting on the season, WNO Artistic Director David Pountney says: “The paradox of music is that it is a highly rational means of expression, much more logically organised than the language of speech for instance, and yet it is at the same time the supreme means of expressing all kinds of extreme emotional states. Among these, madness has been a constant inspiration to composers eager to test the ability of music to penetrate the most radical states of mental disorder. Our season presents a fascinatingly wide range of musical expression dedicated to this phenomenon, from the virtuosic roulades of Handel, via the elegant refinement of Bellini to the raw craziness of Sondheim’s gruesome Barber.”

Wales Millennium Centre will also present WNO in a concert performance of Tosca on Monday 2 November featuring Bryn Terfel as Scarpia. Ainhoa Arteta will perform the title role with Teodor Ilincãi as Cavaradossi. The performance will form part of the finale of Wales Millennium Centre’s 10th anniversary celebrations.

Graeme Farrow, Artistic and Creative Director at Wales Millennium Centre says: “Working collaboratively with our resident partners has always played a fundamental role in our vision to becoming a world class Centre for the arts, and the many successes the Centre has achieved in its first 10 years have been reached with the support and expertise of our residents. It is our ambition in the years to come to create new work of exceptional quality that delights, surprises and impresses. Developing partnerships, within Wales and internationally, is essential in fulfilling this ambition, and it’s a privilege to be collaborating with Welsh National Opera with their inimitable reputation for producing exciting and ambitious opera.”

David Pountney adds: “We are delighted to join with Wales Millennium Centre to celebrate their 10th anniversary. The Centre is one of the finest purpose built opera houses in Europe, and its presence in Cardiff has transformed opera making for us, and opera going for people from Wales and far beyond. As such, it is an invaluable asset to Wales’ cultural portfolio, and a symbol of its aspiration to the highest levels of artistic expression and achievement.”

Following the autumn tour, WNO will present two performances of A Christmas Carol at Wales Millennium Centre in December; Iain Bell’s adaptation of Charles Dickens’ Christmas favourite. This seasonal show will be an opportunity to experience Bell’s work prior to the world première of In Parenthesis during WNO’s summer 2016 season. The one-man show will feature tenor Mark Le Brocq as Narrator alongside a chamber orchestra. Conducted by James Southall, the production will be directed by former WNO Genesis Assistant Director Polly Graham.

More information on WNO’s autumn 2015 season is available at wno.org.uk

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Wales_Millennium_Centre.png image_description=Wales Millennium Centre product=yes product_title=Press Release: Welsh National Opera explores Madness for autumn season product_by= product_id=Above: Wales Millennium CentreJune 25, 2015

A Chat with Pulitzer Prize Winning Composer Jennifer Higdon

The following year she won the Pulitzer Prize in Music for her violin concerto. On August 1, 2015, her opera, Cold Mountain, will have its world premiere at Santa Fe Opera. On June tenth, I phoned her for an interview to be published in Opera Today and was greeted by a friendly, “How ya doin?”

MN: Where are you from?

JH: I was born in Brooklyn but we moved to Atlanta, GA, when I was six months old. Later, we moved to Seymour, TN, near Knoxville. After high school I went to Bowling Green State University in Ohio where, during my last year of undergraduate work, Robert Spano led the university orchestra and I was allowed to study conducting with him. Although I did not see him for a number of years after that, he was the first to record one of my orchestral works. He is a great champion of contemporary music. I got my master’s degree and doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania. I also have an artist diploma from the Curtis Institute, which is a really great school. Currently, I occupy the Milton L. Rock Chair in Compositional Studies there.

MN: George Crumb is said to define music as "a system of proportions in the service of spiritual impulse." What did you learn from him at the University of Pennsylvania?

JH: I learned how to handle instruments and think beyond the norm. His extended techniques on the instruments are always unusual and sometimes unique. Examples of extended techniques might include bowing under the bridge of a string instrument, blowing into a wind instrument without a mouthpiece, or inserting objects on top of the strings of a piano. Crumb is very inventive and he made me think about color a great deal. Many of today’s listeners think of music in terms of its rhythm. That may be one of the reasons for the popularity of my music, which usually has a strong rhythm.

MN What do you play besides the flute and how do you handle composing for instruments you don’t play?

JH: I play the flute and a little bit of piano. You’re right, it’s not easy to write for the instruments I don’t play. (She adds with a knowing laugh). I have to be sure to learn a great deal about each instrument because I don’t play most of the instruments for which I am composing. It’s a pretty big thing.

MN: When did you start composing?

JH: I began during my undergrad days. I was about twenty years old and had been working on a performance degree for a couple of years. I know some people have started composing as children. I am a late bloomer who taught herself to play the flute at age fifteen. I did not begin to study music formally until I was eighteen and went off to college. At Curtis I was unusual. Most of the students had begun music lessons at the age of three or four.

MN: How did you meet violinist Hilary Hahn?

JH: She was in a class I taught entitled Twentieth Century Theory and Music History. It was a fun class to teach and a serious responsibility because the amount of material to be covered between 1900 and 1999 is enormous. The class is a requirement for all Curtis students.

MN: The end of the last century produced a great deal of dissonant music. Are we now returning to melody?

JH: Oh yeah! People are asking for more melodic music. My new opera, Cold Mountain, is definitely melodic.

MN: Do you have a routine for composing?

JH: I write every day. For two years while composing the opera, I wrote eight hours a day, seven days a week because I felt that was absolutely necessary. Writing an opera has been very different from composing symphonic or chamber music. It simply does not feel at all the same. I did not expect composing an opera to be that different, but I knew it was the minute I started working on it.

MN: How do you allow for individual differences among singers?

JH: It is really the same thing as writing the violin concerto for Hilary Hahn and then having other violinists play it. I just had to make the best possible guesses. Before I composed Cold Mountain I knew that Nathan Gunn would sing the leading part of Inman, but I did not know who would sing the other roles. Later, we selected the renowned Isabel Leonard to sing Ada and Emily Fons, who made a fine impression as Zerlina in the San Diego Opera Don Giovanni, to be Ruby. The Siegfried from the Met’s HD Ring Cycle, Jay Hunter Morris, will be the villain, Teague. Ticket sales for Cold Mountain have been impressive. The first two performances are already sold out.

MN: How did you come to work with Gene Scheer?

JH: When I realized that I was going to write an opera, I knew I needed to work with an experienced librettist. I asked a lot of people for recommendations and the consistent answer was Gene Scheer. We got together for lunch and within five or ten minutes I knew that he would be ideal. We connected. It was important because composer and librettist spend a lot of time discussing creative ideas. When you’re going to work with a person for a long time, it’s important to choose someone with whose personality you are comfortable.

MN: I’m told Cold Mountain has more than twenty scenes. How did you decide which parts of the book to use?

JH: We primarily followed the three main characters, Inman, the hero, Ada and Ruby. We searched for scenes that advanced the story and showed the changes that occurred to in those characters. An opera has to have strong roles. I just looked for situations that resonated with me. You live with an opera for a long time so you need to feel it. We also needed scenes that presented good musical possibilities. We both read the book over and over.

MN: Where does Cold Mountain go after Santa Fe?

JH: It goes to Opera Philadelphia, which will present it in February of 2016. Cold Mountain will be part of their American Repertoire Program, which is committed to produce an American work in each of ten consecutive seasons. It then goes to Minnesota Opera, which tentatively plans to stage the opera in its 2018-2019 season. It will be part of Minnesota Opera’s New Works Initiative. Many more companies have asked about it as well but nothing is firm enough to talk about yet. I expect that Cold Mountain will be recorded as well.

MN: What is next for you?

JH: I’ve already written six pieces since I finished the opera. I did a song cycle for Thomas Hampson that he premiered at Carnegie, and a viola concerto commissioned by the Library of Congress. I had a whole bunch of commissions stacked up. Right now, I’m writing a string orchestra piece for Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg and her group, The New Century Chamber Orchestra. She will premiere it in San Francisco in early May 2016. I’m working on that right now. I’m also looking at subjects for another opera. I also have other pieces coming down the road so I have quite a bit on my plate. I have work lined up until 2020. I only teach two hours a week at Curtis so most of my time is spent composing.

MN: Do you have any stories about recent events?

JH: A couple of weeks ago the White House called me and left a message wishing me well for Cold Mountain. I get recognized now. Sometimes I get stopped on the street, which surprises me. One time when my wife, Cheryl, and I were in the Delta Airlines Lounge in Paris a kid came up to me and asked if I was the composer of the violin concerto that Hilary Hahn had just premiered.

MN: Do you have time for a private life?

JH: Cheryl and I like to watch movies and travel when we can. I have to admit I have so much going on right now that my career takes up most of our time. Once the work on the opera got going, everything else slowed down and I did far fewer residencies than usual. My life is really full and it’s lots of fun. I feel very fortunate that I get to make my living writing music. That’s sheer heaven.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Higdon-Smile-1.png

image_description=Jennifer Higdon [Photo by J. Henry Fair]

product=yes

product_title=A Chat with Pulitzer Prize Winning Composer Jennifer Higdon

product_by=An interview by Maria Nockin

product_id=Above: Jennifer Higdon [Photo by J. Henry Fair]

June 23, 2015

Death in Venice, Garsington Opera

And yet, risks have been taken, with surprising and stimulating results. Yoshi Oida’s 2007 production is more Japanese minimalism than Venetian splendour, and when revived by Opera North at Snape in 2013, Tom Schenk’s set designs exploited the natural fabrics of the Snape Maltings Hall for which the production was designed. Deborah Warner’s 2007 ENO production, though the stage is largely bare, manages to suggest through movement and light both an exquisitely sumptuous décor and a melancholy barrenness of soul.

Kevin Knight’s designs for Paul Curran’s new production for Garsington Opera offer both orthodox Venetian motifs and striking abstraction. A sand-coloured floor curves up, like a wave in the lagoon, meeting a Turner-esque blue sky; upon the horizon, the familiar shoreline is intermittently projected. Bruno Poet’s lighting bathes the shore in golden sunbeams, then bleaches it with the pallor of sickness; the gleaming beauty of La Serenissima casts its heavenly illumination, before the dull shadows of canal-borne disease darken the hues.

The stage is bare; in place of set and props we have four billowy white curtains which intersect on the diagonal, wafting in the nascent scirocco humidity. These curtains serve to separate Aschenbach from reality, to trap him in the cold sterility of his intellect. Their whiteness is both the creative purity of Apollonian discipline and the emotional emptiness of a life repressed. They part to reveal the city and its inhabitants; they frame the gondola that bears him southwards; they close to prevent communication. So far, so good: but the ceaseless swishing back and forth of these drapes becomes rather tedious after two and a half hours. And sometimes the abstraction is imprecise or misleading. As Aschenbach strolls dejectedly amid the suburbs of an imagined Munich, the Traveller appears in an imagined cemetery; but, through the drifting chiffon we glimpse smartly dressed tourists promenading along the Venetian strand – is Aschenbach envisioning a journey that he does not yet know he will shortly undertake? The absence of a set also necessitates the never-ending carriage of esplanade benches, hotel sofas, anteroom palms and other paraphernalia to suggest the various locations in which Aschenbach’s demise unfolds.

Celestin Boutin as Tadzio and Nina Goldman as Polish Mother

Celestin Boutin as Tadzio and Nina Goldman as Polish Mother

There’s a lot of to-ing and fro-ing. Indeed, movement takes centre-stage in this production, in which Curran and his choreographer Andreas Heise prioritise and supplement the opera’s dance episodes. The choreography for the five male dancers blends classical balletic grace with striking muscularity. The powerfully persuasive gestures draw just about everyone into the dance: Tadziu’s mother (Nina Goldman), governess (Georgie Rose Connolly), siblings (Minna Althaus and Poppy Frankel), even the strawberry seller (Emily Vine) are swept up in the athletic arabesques.

The set-pieces hook our attention but, in their erotic evocations, often go far beyond the allusion and suggestiveness of Myfanwy Piper’s libretto and Britten’s score. Apollo is no longer a disembodied voice, but rather appears in person, attired in golden cloak and laurel crown – both a deity of pure light and a dangerous sun-god – to oversee the Games which bear his name, and which are watched by a chorus of sinister Carnival-goers: harbingers of death, clad in black hooded cloaks and gold-leaf masks. Tom Verney’s countertenor is not a voice of ethereal purity or the honeyed mellifluousness of Elysium, but his unearthly cries certainly emphasise the ‘unnaturalness’ of the god’s pronouncements, sending a chill down the spine if not always complementing the beauty of the beach Games’ vigour. Here, Heise’s gestures drew directly and precisely upon the text: the running race was a frenetic tumult of ‘flashing forms’ and ‘working arms’; the dancers used astonishing elasticity to ‘spring high’ and ‘shoot forward’ in the long jump; ‘swinging up and back’, they swirled hypnotically in the discus. The tightly wound formations of the final game reached the height of erotic tension: ‘forehead to forehead/ fist to fist/ limbs coiled around limbs/ panting with strain’, they youthful competitors lifted Tadziu aloft, to the pervasive reverberations of harp, double bass, pizzicato cello, gong and tom tom.

These Games of Apollo anticipate Aschenbach’s subsequent Dionysian dream. Again, the gods do battle, not within the writer’s troubled psyche, but on the stage before us, as the revellers’ shrieks, ‘Aaoo!’, blend with the violently pulsing uproar of the drums and the terrible sweetness of the flute. Although Piper had initially noted that it would be necessary to ‘avoid the obviousness of the homosexual theme’, she later made the well-intentioned but somewhat naïve suggestion that during the second beach ballet the boys should be ‘really naked so as to remove the whole thing slightly from reality, as the whole of Aschenbach’s attitude is removed from reality’; Britten thought this was an excellent idea, which ‘could be wonderfully beautiful, Hellenically evocative’, but the plan was later, and perhaps fortunately, abandoned. Curran, however, follows Piper’s suggestion and the Dream ends with Tadziu being stripped of his sailor-suit by the carousing hordes, who caress and writhe around his naked legs. Hellenic evocation seems far from Curran’s mind in this Dionysian nightmare …

Even the Travelling Players’ suggestive lewdness is transformed into outright vulgarity, as four male dancers indulge in mock offensiveness, raising their skirts to expose their be-trousered behinds to the hotel guests, and engaging in faux sodomy.

The remarkable central energy in the production is Celestin Boutin’s mesmerising Tadziu. It’s impossible to state unequivocally how old Tadziu should be or look but, despite his blond curls – which, like some of the visual vignettes, seem to allude to the first performance by dancer Robert Huguenin to whom Peter Pears’s Aschenbach fell victim – Boutin’s physical maturity and strength, and sheer brazenness, foreground the physical over the spiritual. Mann’s text formulates a theory relating beauty to man’s spiritual and intellectual purity: beauty partakes in a higher reality, a world beyond corruption where the artist seeks to create his work. Boutin, however, is too physical to be god-like; not a statuesque divinity but a mortal tempter.

Paul Nilon (Aschenbach) with Company

Paul Nilon (Aschenbach) with Company

Boutin’s first entrance did convey a timeless immobility; the drums were silenced by the shimmering vibraphone as he stepped slowly across the stage, relishing the onlookers’ admiring gaze. Certainly, Britten and Piper suggest that Tadziu shares the incipient knowingness and coquetry of Miles in The Turn of the Screw; he is on the cusp of sexual awakening. But, Boutin boldly exults in the intensity of veneration. Moreover, by making Tadziu mute, Britten suggests that any communication and consummation between Aschenbach and the Polish boy is impossible: he is not a ‘real’ boy, but an idealization. In Curran’s vision, though, Tadziu’s allure is all too ‘flesh-and-blood’. The score’s invitational glances become physical advances, most notably at the end of Act 1 as the boy reaches out to brush the straining fingertips of the infatuated Aschenbach.

In the title role, Paul Nilon presents an astonishingly powerful portrait of physical and moral decline. Nilon’s tenor is dark-coloured and plangent, and he delivers the writer’s self-castigating monologues with unwavering dramatic focus, smoothing over the florid verbosity of Piper’s lengthy, high-falutin monologues with their heavy-handed symbolism and indulgent Hellenic philosophising. Every word is clearly enunciated and the free recitatives are thoughtfully phrased.

Nilon’s Aschenbach is the embodiment of emotional anguish – and, surprisingly animated, swinging wildly from joy to despair. The self-restraint of the opening moments is quickly swept away by fatal passion; this Aschenbach does not languish in the hinterland, wearied and depleted by his self-consuming devotion, but endeavours to engage directly with the object of his adoration. Denied, by a hair’s breadth, the ecstasy of physical touch at the end of Act 1, his howl, ‘I – love you’, drains into a desperate sob: the moral and artistic discipline which have upheld his entire life have been brutally shattered by self-honesty, as foreshadowed by the Traveller at the start of the Act, when he tears and scatters the pages of the esteemed writer’s book before throwing the latter disparagingly to the ground. In Act 2 Nilon’s decline is rapid and disturbingly palpable; and it is enhanced by the potent lighting design as Poet takes advantage of the looming darkness, conjuring volatile shadows which convey the protagonist’s fragmentation and torment. After his visit to the barber, Aschenbach abandons all pretence, clutching frenetically at the alarmed hotel guests as they prepare to depart, seemingly indifferent to his own humiliation and disgrace.

William Dazeley is excellent in the composite role of the Traveller-Elderly Fop-Gondolier-Hotel Manager-Barber-Leader of the Players-Dionysus, metamorphosing between these disparate incarnations with sinister ease. Dazeley’s bass may not quite be sufficiently deep-toned for the Hadean Gondolier, but he was firm-voiced and authoritative as the mysterious Traveller and bright and energised as the Hotel Manager, transforming his voice skilfully. The falsetto of the Leader of the Players and the Barber eerie echoed the Elderly Fop of Act 1, confirming the compound figure’s role as a deathly herald.

In the minor roles, baritone Henry Manning was a fine English Clerk/Youth, announcing the arrival of the cholera with clarity, while tenor Joshua Owen Mills was a confident, bright-voiced Hotel Porter. The Garsington Chorus was superb, suavely embodying the European clientele at the Lido Hotel and forming an impassioned band of Dionysian followers. As hawkers and beggars, they straggled along the esplanade, pestering and troubling the protagonist; as youthful travellers, they soothingly crooned the Serenissima theme.

William Dazeley (Leader of the Players) with Company

William Dazeley (Leader of the Players) with Company

Undoubtedly, the coherence and impact of this production owes much to conductor Steuart Bedford. Bedford conducted the first performance of the opera at the Aldeburgh Festival on 16th June 1973, and the passing of forty-two years has only served to strengthen his appreciation of the role of precise motivic and timbral details within the overall structure, and of the musical and narrative trajectory of the work. We heard every instrumental detail, the Garsington Opera Orchestra playing with intensity and precision. Flamboyant harp glissandi, throbbing timpani outbursts, the dark rumbles of the tuba, penetrating string lines and eloquent woodwind solos created a concentrated sound-world which drew us into the evolving psycho-drama. But there was warmth too, as when the ‘view theme’ expanded with a softening gleam.

Some productions err on the side of ambiguity and elusiveness, the suggestive exoticism of the score counterbalanced by the text’s Platonic theorising. For, while one might suggest that in Death in Venice Britten located an explicit account of the energies which had for so long been strong undercurrents in his operas, there remains an evasive mist and there is little direct disclosure in Piper’s libretto.

But Curran doesn’t hedge his bets – the forces released when Aschenbach opens the heart which has for so long been imprisoned by artistic discipline and repressive self-respect are dark and deadly. When Britten was composing Death in Venice – during which time he was suffering from acute heart arrhythmia – Peter Pears is reported to have told the Australian painter, Sidney Nolan: ‘Ben is writing an evil opera, and it’s killing him!’ And, Curran presents us with what Ronald Duncan called ‘the public revelation of a private agony’; the danger Duncan foresaw when ‘imagination and reality become fused and identified’ is painfully played out. The final image is a disquieting master-stroke: lured by the enticing silhouette of Tadziu visible through the gauzy white hanging, Aschenbach leans forward, arms outstretched – but, at the moment that it seems their hands might at last touch, the lighting abruptly switches, the profile fades and all that remains for Aschenbach is his own lurching shadow.

Aschenbach had hoped, ‘The power of beauty sets me free’. In the event, it is Socrates whose words prove more germane: ‘beauty leads to passion, and passion to the abyss’. Curran seems to be urging us to ask, as did Peter Pears[1], if the pursuit of beauty and love must always lead only to chaos?

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Gustav von Aschenbach, Paul Nilon; The Traveller, William Dazeley; The Voice of Apollo, Tom Verney; Hotel Porter, Joshua Owen Mills; English Clerk, Henry Manning; Polish Mother, Nina Goldman; Tadzio, Celestin Boutin; Governess, Georgie Rose Connolly; Jaschiu, Chris Agius Darmanin; Conductor, Steuart Bedford; Director, Paul Curran; Designer, Kevin Knight; Lighting Designer, Bruno Poet; Choreographer, Andreas Heise;Garsington Opera Orchestra and Chorus; Parsifal James Hurst, Garth Johnson, Alexandre Gilbert, Ygal Jerome Tsur (Dancers). Garsington Opera at Wormsley, Buckinghamshire, Sunday 21st June 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/150618_0135-deathinvenice-adj.png image_description=William Dazeley as the Old Gondolier and Paul Nilon as Aschenbach [Photo by Clive Barda] product=yes product_title=Death in Venice, Garsington Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: William Dazeley as the Old Gondolier and Paul Nilon as AschenbachPhotos by Clive Barda

June 22, 2015

La Rondine Swoops Into St. Louis

Tosca, Boheme, and Butterfly may be the bread-and-butter operas, but La Rondine can prove to be a highly satisfying sorbet, a lighter weight dalliance that nonetheless has its share of memorable melodies. Witness that during the first act intermission, the audience was mingling humming Doretta’s Song, almost against its will. After Act Two the line at the bar was having a go at the famous ‘Ohrworm’ from the quartet. Giacomo could sure write a tune! What he couldn’t do in this case, was make up for the fact that in Giuseppe Adami’s libretto, nothing much really happens.

No Japanese honor suicides, no offing of villainous police chiefs, no worrisome consumptive coughing, nada. All we have here is a bored demimondaine who decides to go slumming at a lower class Parisian bar, falls instantly in love with a young visitor, chucks all the wealth to be with him, but then pretty much gets bored again and leaves him flat. Now Puccini himself made a good deal out of a similar scenario in the youthful Manon Lescaut, which bristles with passion. But in La Rondine there is really nothing at stake.

John McVeigh as Prunier and Corinne Winters as Magda

John McVeigh as Prunier and Corinne Winters as Magda

That puts a heavy burden on the performers to flesh out the consequences of their decisions and make you “feel their pain.” And to a large extent director Michael Gieleta and his accomplished cast and collaborators did just that.

Set Designer Alexander Dodge has created a marvel of a paneled box set drawing room, that at once evokes the confines of the Parisian salon where the story begins, and the freedom of the Nice seaside, where it ends. This is accomplished by an overall blue hue, with the bottom five feet or so subtly textured to resemble the sea. Gieleta and Dodge further choose to begin each act with a pre-set beach chair down center (soon struck) to presage the final act (when more chairs are added). The upstage “wall” is mostly a curtain, which pulls to reveal a platform that first contains Bullier’s tavern in Act Two, and then becomes a boardwalk and row of cabanas in Act Three. Very effective and attractive playing spaces, all.

Mr. Gieleta moves his forces about these environments exceedingly well. With the salon being dominated by a massive dining table, he invents any number of clever stage pictures while always maintaining good focus. I liked rolling in the piano from stage right when it is required for Doretta’s Song. In Two, the revelers vary between being contained on the tavern platform, or spilling onto the street which gets decorated with poles and strings of beer garden light bulbs as part of the action.

By Act Three, I began to fully appreciate the levels that Mr. Dodge created with not only the upstage platform, but by having the downstage drop off right and left of a central platform, to give three different heights. The director took full advantage of the possibilities, to include having Magda change clothes in her boudoir on the lower right level before dashing out on the town.

John McVeigh as Prunier, Corinne Winters as Magda, Ashley Milanese as Yvette, Elizabeth Sutphen as Bianca, and Hannah Hagerty as Suzy

John McVeigh as Prunier, Corinne Winters as Magda, Ashley Milanese as Yvette, Elizabeth Sutphen as Bianca, and Hannah Hagerty as Suzy

Gregory Gale contributed truly sumptuous costumes for the rich guests in the first act, then took it down a notch with colorful middle class street wear (and soldiers’ uniforms) in the Second Act. His casual beachwear in Three was simple and comfortable. This was beautifully detailed work. Only one thing bothered me and that was that Magda’s “simple black dress” that she wears out on the town kept parting in the front revealing her bloomers. Intentional? Hmm.

Christopher Akerlind made some bold lighting choices, with sharp rectangular specials, moody washes, and heightened, almost abstract atmospheres. It did inject a rhythm and visual excitement missing from the story. Tom Watson’s hair and make-up design was exceptional in delineating classes and temperaments.

Veteran Stephen Lord conducted a knowing, stylistically comfortable reading, and the musicians responded with generous playing that made them sound more lush and imposing than their numbers might imply. His communication with the singers was sensitive and the show breathed and surged as Puccini must. Maestro Lord also had a keen sense of pace and I was especially appreciative that he did not let the singers get too indulgent in the lovely, but repetitive quartet.

The chorus of Gerdine Young Artists performed superbly as trained by Chorus Master Robert Ainsley. Puccini has filled out much of the first two acts with choral effects, and they all made their impression. If you would take the time to look at the cast list, please realize that once you are past the first five names, all of the rest of the featured roles were taken with laudable and applaudable results, by members of the Gerdine Young Artists. These promising, talented singers covered themselves in glory the whole night., and they remain the heart of OTSL.

Anthony Kalil as Ruggero and Corinne Winters as Magda

Anthony Kalil as Ruggero and Corinne Winters as Magda

Matthew Burns brought admirable suavity and a bit of gravitas to Rambaldo’s scolding and blathering. As Lisette, the animated Sydney Mancasola was a delight, and her well-focused flights of fancy fell easily on the ear. Her enchanting portrayal was exceedingly well sung. John McVeigh, as Prunier, threatened to walk away with the show. Arguably the most complete characterization on the stage, McVeigh put his playboy good looks in service of creating a most lovable cad. John also sang with real refinement, his honeyed tenor encompassing all of the role’s demands.

Tenor Anthony Kalil is a big tall bear, a physical trait that might naturally work better for a bumbling-but-lovable Nemorino than for an OMG-love-at-first-sight Ruggero. That said, Mr. Kalil has an impressive, incisive tenor instrument. His ringing sounds filled theatre with real Puccinian squillo. His future seems assuredly bright.

Corinne Winters has all the necessary attributes for Magda. She is lovely and elegant. Her soprano can soar with the best of them, and her intelligence and attention to detail are second to none. Her seamless vocal production seems to have darkened just a bit since last I heard her, making her lower middle more forward placed. This resulted in some loss of diction in that range, especially when sustained banks of strings were playing. Ms. Winters made Doretta’s Song the showpiece it must be, and sang with luster throughout.

Whether it was her choice or the director’s, I found it hard to warm to her until well into Act Two. For all its vocal virtues, her Magda seemed too arch, too above it all. It improved and Corinne and Anthony sang the final scene very well indeed. But, while every phrase was well calculated, and every effect wholeheartedly attempted, I was longing for some real chemistry, some emotional connection, rather than two marvelous performers singing beautifully to the back wall. Both of these artists could deliver that real heartbreak with just a modest change in blocking and focus.

Everything about La Rondine was first class, and I greatly admired it. But I wanted to be touched by it. Truth in reporting, the audience received it rapturously.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Magda: Corinne Winters; Lisette: Sydney Mancasola; Ruggero: Anthony Kalil; Prunier: John McVeigh; Rambaldo: Matthew Burns; Suzy: Hannah Hagerty; Yvette: Ashley Milanese; Bianca: Elizabeth Sutphen; Gobin: Joshua Wheeker; Crébillon: Erik Van Heyningen; Périchaud: Luis Alejandro Orozco; Butler/Major Domo: David Leigh; Adolfo: Charles Sy; Rabonnier: Josh Quinn; Two Singers: Liv Redpath, Joshua Blue; Two Young Women: Jessica Faselt, Stephanie Sanchez; Grisettes: Anna Dugan, Lilla Heinrich Szász, Ann Toomey; Student: Todd Barnhill; Conductor: Stephen Lord; Director: Michael Gieleta; Set Design: Alexander Dodge; Costume Design: Gregory Gale; Lighting Design: Christopher Akerlind; Wig and Make-up Design: Tom Watson; Chorus Master: Robert Ainsley

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Rondine15.png

image_description=Corinne Winters as Magda and Anthony Kalil as Ruggero [Photo © Ken Howard]

product=yes

product_title=La Rondine Swoops Into St. Louis

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Corinne Winters as Magda and Anthony Kalil as Ruggero

Photos © Ken Howard

Emmeline a Stunner in Saint Louis

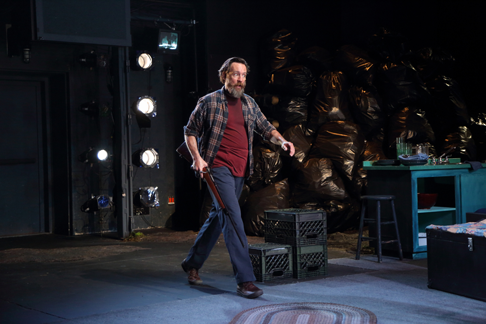

Celebrating its fortieth anniversary, OTSL’s current season has favored us with a stunning new production of a late 20th Century masterpiece, Emmeline by composer Tobias Picker and librettist J.D. McClatchy. The piece was commissioned by Santa Fe Opera where it premiered in 1996. Having garnered glowing reviews and international attention, Emmeline was mounted to similar acclaim at New York City Opera in 1998. And then, like Evita’s corpse, it inexplicably disappeared. . .

Or almost. There was a scattering of scaled back performances, but the current revival is the first major full scale production in seventeen years. I would hope that the persuasive performance I experienced in the Gateway City might inspire other companies to similarly embrace its manifold riches.

First, Mr. Picker has fashioned an accessible, melodic score that nonetheless crackles with contemporary musical commentary and post-modern invention. The orchestral writing is lush one moment with undulating layers of overlapping neo-romantic strings, then jagged and impulsive the next with jittery winds skittering nervously above and around a cantus firmus.

Folk melodies are hinted at, although only Rock of Ages is a real quote and at that, it is ornamented with a disturbing subtext, a parody of a rather hysterical country fiddle. When tragedy looms there is an imposing, heart-sickening stretch of ominous themes intoned in quadruple (quintuple?) octaves that pierces the soul.

Nicole Haslett as Sophie and Joyce El-Khoury as Emmeline Mosher

Nicole Haslett as Sophie and Joyce El-Khoury as Emmeline Mosher

Best of all, this is Picker’s most accomplished vocal writing. Mr. McClatchy’s lean, mean libretto has nary a false move, and the composer responds with appealing, straight forward declamations that are natural yet pleasing to the ear and appropriate to the situation. When things get more heated, the composer uses the text as a springboard to craft escalating lines of arching intensity, mounting musical tension, and cataclysmic dramatic resolution.

In later operas (An American Tragedy, Dolores Claiborne) I sometimes felt Picker occasionally unnecessarily taxed the vocalist to, and sometimes beyond their limits. Not so here. Every phrase of Emmeline seemed apt, inevitable, and well considered.

In the pit, George Manahan commanded a compelling reading that found every soaring statement, every telling nuance in place. The Maestro elicited superb colors from his band and found an unerring balance with the stage. He ably partnered the drama at every moment, nay, he prodded it forward, in a thrilling reading that was by turns edgy, serene, searing, soaring, contemplative, and bombastic. Mr. Manahan has a reputation for drawing inspired work from instrumentalists and vocalists in such “new” works, and he united his forces in a spellbinding ensemble.

The title role is a tour de force for a soprano, and the original Emmeline, Patricia Racette found her career kicked into high gear with her Santa Fe success. I have no doubt the same should happen with the current star Joyce El-Khoury. She is luminous in the part. (Ms. Racette was in attendance opening night at OTSL to cheer on her successor.)

Ms. El-Khoury had it all. She is possessed of a substantial lyric voice that has spinto leanings. Her sound technique allows her to encompass every diverse requirement of the score. She has an attractive and appealing stage presence, and her stage savvy allowed her to completely immerse herself in the emotional journey of the unfortunate girl. And oh, the things she is called upon to communicate!

Emmeline is first used by her poor family. She must leave home and become the bread winner by working in a de-humanizing mill. When her loneliness leads her to become impregnated by her married employer, the family derides her. She never sees the child that is taken from her at birth. She matures into an aloof caretaker of her ineffectual parents, but then a young man unexpectedly enters her life, and they eventually marry. Emmeline soon discovers in horror that she has had an incestuous relationship with the son she had never known. Abandoned, she remains resolutely steadfast in her motherly love for her son. Such is the stuff of great tragedy.

Nicole Haslett as Sophie, Joyce El-Khoury as Emmeline Mosher, Renee Rapier as Mrs. Bass, and Geoffrey Agpalo as Hooker

Nicole Haslett as Sophie, Joyce El-Khoury as Emmeline Mosher, Renee Rapier as Mrs. Bass, and Geoffrey Agpalo as Hooker

This dramatic evolution afforded ample opportunity for Ms. El-Khoury to regale us with the full gamut of a singers arsenal: gleaming phrases poured out above the staff, invectives hurled with fire and conviction, plangent utterances of despair, melting professions of radiant romantic happiness, and introspective pianissimo singing that touched the soul. Joyce El-Khoury’s Emmeline is the gold standard against which all future interpreters will be measured.

As her strapping son Matthew Gurney, tenor John Irvin was appealingly boyish and irresistibly charming. He used his secure, brightly focused lyric tenor to create a most engaging portrait. Mr. Gurney exhibited a fearless precision as he executed each and every high-flying outburst that the composer devised for the impassioned lad (some seemed scored where only dogs can hear!), while also commanding a warm and appealing sweetness as the situation required.

Meredith Arwady as the manipulating and judgmental Aunt Hannah proved once again to be a force of nature. I have always admired her, but this is her very best work to date. The part is tailor-made to her gifts, which includes those rock solid, sternum rumbling chest tones. Ms. Arwady’s top voice, on this occasion, was just as thrilling. It glistened with laser intensity. The voice is a seamless whole, and this performance may be one of those magic occasions where you have witnessed a major singer hitting the very top of her game.

Wayne Tigges is always a reliable and conscientious performer, and he does not disappoint as the seducer Mr. Maguire. Like Cornell MacNeil, he has such an imposing, steely instrument that I am always surprised by his ability to suddenly change gears to apply a sudden supple use of vocal colors and shading. The role lies high for him (or anyone else), but Mr. Tigges negotiated the angular leaps with skill, even if his baritone can tend to a bit of unruliness approaching the passaggio.

The entire ensemble cast proved to be of the highest standard. Renée Rapier made her mark as Mrs. Bass, the school-marmish owner of the boarding house. Ms. Rapier sang with clarity and finesse, and communicated a completely realized character (thanks in part to Tom Watson’s effective wig and make-up design). Mill girl Sophie was assumed by Nicole Haslett who sported a shining, fresh soprano in a fiery and sympathetic performance. She was complemented by a nice turn from Lilla Heinrich Szász as millworker Ella, who offered a limpid, pure vocal characterization.

John Irvin as Matthew Gurney and Joyce El-Khoury as Emmeline Mosher

John Irvin as Matthew Gurney and Joyce El-Khoury as Emmeline Mosher

As the mean-spirited sister Harriet, Felicia Moore was every inch the woman-we-love-to-hate. Her solid singing was tinged with spite and provocation. Pastor Avery was well-served by Daniel Brevik’s ample bass. Erik Van Heyningen’s pleasing baritone shone in the brief phrases allotted to Simon Fenton. Matthew Lau’s characterful baritone struck just the right note as the hapless father Mosher. As Hooker (the factory foreman, not a lady of the night) Gerdine Young Artist Geoffrey Agpalo just flat out nailed the part, as much for assured temperament as for spot-on stratospheric outbursts of steely tenor tone. Mr. Agpalo won a deserved ovation at curtain call for his impressive contribution.

In fact, the afore-mentioned supporting cast was peopled with former and current members of the Gerdine Young Artist Program, one of the company’s glories and a major training ground for performers who often move on to world-wide careers.

An episodic, highly theatrical piece like Emmeline is red meat to director James Robinson, who excels in making riveting, poetic theatre from such source material. Allen Moyer’s well-chosen set pieces were spare and evocative. The paucity of stage clutter suggested the limited means of the characters and the dehumanization of the industrial revolution (the three imposing looms were awesome!).

The company’s new turntable was immediately justified as a worthwhile purchase as Mssrs. Robinson and Moyer put it to effective use beginning with the opening reveal of the family gathered at a funeral. As cast and scenery spun into different positions the effect not only suggested a cinematic cross-fade, but also visualized the shifting emotional states of the leading character. Christopher Akerlind’s haunting lighting design perfectly captured the expansiveness of the bucolic milieu as well is the claustrophobia of societal pressures. James Schuette’s masterful costumes did much to establish time, place and character. The subtle color difference that sets Emmeline apart from the other mill girls in their work dresses is only one of many lovely touches.

But ultimately, it was Robinson’s vision that made Emmeline come leaping to vibrant life on the stage. He ensured that every moment was truthful and focused. His stage pictures evolved naturally. Each transition was carefully choreographed to keep moving the story forward. One beautiful touch was to have Matthew and Emmeline circle the stage and walk past each other repetitiously, pausing to flirt, as the passage of time (and their developing love) was indicated by the yearning orchestral passages.

If there is a better case to be made for the tragedy of poor Emmeline, well, I am not sure my heart could stand it. Opera Theatre of Saint Louis has delivered another definitive performance, one that is a perfect fit for the intimate Loretto Hilton theatre. Is there any space more congenial to experience the immediacy and import of a riveting operatic performance?

Forget about the Arch. Forget about the Cardinals. Emmeline is currently “the” reason to visit Saint Louis.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Emmeline Mosher: Joyce El-Khoury; Aunt Hannah Watkins: Meredith Arwady; Matthew Gurney: John Irvin; Mr. Maguire: Wayne Tigges; Sophie: Nicole Haslett; Harriet Mosher: Felicia Moore; Mrs. Bass: Renée Rapier; Pastor Avery: Daniel Brevik; Hooker: Geoffrey Agpalo; Henry Mosher: Matthew Lau; Townswomen 1, 2, 3: Anna Dugan, Ashley Milanese, Kelsey Lauritano; Simon Fenton: Erik Van Heyningen; Ella Burling: Lilla Heinrich Szász; Conductor: George Manahan; Director: James Robinson; Set Design: Allen Moyer; Costume Design: James Schuette; Lighting Design: Christopher Akerlind; Wig and Make-up Design: Tom Watson; Chorus Master: Robert Ainsley

image=http://www.operatoday.com/EMM_1699a.png

image_description=John Irvin as Matthew Gurney and Joyce El-Khoury as Emmeline Mosher [Photo © Ken Howard]

product=yes

product_title=Emmeline a Stunner in Saint Louis

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: John Irvin as Matthew Gurney and Joyce El-Khoury as Emmeline Mosher