April 25, 2007

MAHLER: Symphony no. 2

Even though Mahler withdrew the program for this and his other symphonies, the programmatic content of these works was well known, and generations of critics and scholars have used those descriptions to interpret the music. At another level, Mahler’s Second Symphony, with its choral Finale in a sense, is a response to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and where the Viennese composer had proclaimed the universality of humanity, Mahler declared the general salvation of mankind in an escatological resurrection that transcends religious doctrine. Musically, this is a work in which the composer combines the otherwise artificial divisions of instrumental and vocal music to create a work that is truly symphonic in the sense that the term was used in the late Renaissance, when large-scale works by Gabrieli used instruments and voices to present texts in a celebratory works.

A sense of celebration sometimes accompanies performances of Mahler’s Second Symphony, in much the same way as occurs with Beethoven’s Ninth. As much as Mahler’s work is heard more often in concerts in the twenty-first century than it was in the first half of the twentieth, the Resurrection Symphony remains a work that is by no means run-of-the-mill. Mahler’s score calls for tight, precise ensemble in both the orchestra and chorus, soloists who must work together seamlessly, and a perceptive conductor who can balance those elements in a composition that assimilates elements symphony, oratorio, and orchestral song. The conductor Ivan Fischer captures such a spirit in this recording that was released in 2006. While the notes accompanying this CD do not contain specific dates, the CD was recorded in September 2005.

With its SACD format, the sound is both effective and appropriate to the style and scope Mahler’s Second Symphony. . Moreover, Fischer’s approach to the score is engaging for the way it results in a musical narrative that conveys the structure of the score. This is apparent in the first movement, in which Fischer gives shape to the various ideas that Mahler develops in the course of the piece. The incisive approach to the opening is indicative of the crispness that Fischer uses to bring out nuances in the first movement, while also respecting the details of the score. He is effective allowing the tempos to suit the thematic content, so that the various phrases sound natural and convincing. Yet when the score dictates, he brings out the rhythmic figuration that contributes to the overall ethos of the movement, the Totenfeier Mahler used to set in motion the larger structure of the work.

In the first movement, for example, the he allows for the kind of flexibility that makes the phrases meaningful and, at the same time, refrains from anything idiosyncratic or excessive. the dynamic levels support the musical phrases, and while some timbres may be prominent for a moment, they are never distractingly overdrawn or exaggerated. The marchlike character of the first movement is never achieved at the expense of the lyrical themes that Mahler used in it, and this demonstrates the strategic thinking that is characteristic of this fine new recording. Without becoming slavishly literal with the details that are essential to this movement and the others in the Symphony, Fischer uses the markings as a point of departure for this interpretation, such that the flute solo in the first movement can become a kind of dialogue with the solo violin and it is possible to hear the subtle shifts of tone color that support the structure of the work. These kinds of nuances are evident in the performance, and the quality of the record brings out such gradations quite well.

The fine recording quality found in this particular is noticeable in the second movements, where the various string textures are critical to its success. critical for the second movement, where the string sound must be heard in all its detail. The sometimes close recording is hardly out of place here, as it can be sometimes hard to hear in a live concert. Even though the recording levels capture the details, the winds never sound out of balance, but fit nicely into the timbre that Fischer has created in this movement.

Such attention to detail is not unique to the first movement, but found throughout the Symphony. With the percussion passage that opens the third movement, for example, the crispness and precision of this recording conveys a sense of immediacy that sets the tone for the rest of the movement. Proceeding from that point, the various motifs emerge disstinctly, and when the melismatic phrases from the song “Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt” occur, the lines are clearly articulated. Fischer’s reading of this movement is emblematic of his approach to the entire work, and he achieves a convincing whole that benefits from the attention he has given to the details that are part of it.

The vocal movements are also well done, with Fischer’s reading of the song “Urlicht,” the fourth movement, achieving an appropriate contrast to the ironic and sometimes aggressive character of the movement that preceded it. Birgit Remmert is quite moving in this piece, and her intonation is quite effective. Her alto voice fits the work well, as does her phrasing. The accompaniment is properly supportive of her voice, and as the orchestral becomes more animated, it blends well into her more impassioned sounds, especially with the lines “Da kam ein Engelein, und wollt’ mich abweisen” (“Then a little angel came, and wanted to turn me away”). From there, the song reaches it climax, and ends convincingly, thus setting up the final movement.

In the Finale, Fischer has a fine control of the architecture of the work as well as the forces involved in executing it. The sound quality, as in the other movements, conveys the textures well. The pizzicato accompaniment to the “Auferstehung” theme in the first section of the Finale is, for example, clear and clean, and in this and other places the balance is fine. At the same time, Fischer’s expressive palette includes an effective use of tempos that support the thematic and timbral content. Thus, the forte and fortissimo passages that Mahler uses to underscore the structure are effectively controlled in expressing the swelling phrases that precede the march prior to the choral entrance. There, too, the drum rolls are broad without being uncharacteristically overplayed. The offstage brass fit nicely into the sound plan of Fischer’s reading of this score.

Likewise, the choral entrance is effective, and the softer, almost sotto voce, passages are richly balanced, with the full texture quite moving the when the music demands a louder dynamic. At the same time, Lisa Milne’s voice emerges well front the ensemble, with a soaring tone that serves well in this work. In the vocal duet, Remmert and Milne work well together, and the sense of urgency that Fischer introduces in the orchestra gives the section the dramatic tension it requires. Such tension carries forward in the remainder of the movement, which presents the tableau of resurrection in a moving reading. Fischer brings the work to its conclusion in a recording that deserves attention for its remarkable sonic and musical qualities. This is a vivid performance that is served well by the recording quality. As the work ends, one almost expects to hear the applause that accompanies a live performance.

James L. Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mahler2.png image_description=Gustav Mahler: Symphony no. 2 in C Minor. product=yes product_title=Gustav Mahler: Symphony no. 2 in C Minor. product_by=Birgit Remmert, alto, Lisa Milne, soprano, The Hungarian Radio Choir, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Ivan Fischer, conductor. product_id=Channel Classics CCS SA 23506 [2CDs] price=$27.49 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=7537&name_role1=1&comp_id=1801&genre=66&bcorder=195&label_id=123Beverly Sills & Placido Domingo

For vocal artists, this often means a career retrospective. Deutsche Grammophon has the “Portrait of the Artist” series, double-CD sets promoting mostly its current roster of artists — including a relatively new star, such as Magdalena Kozena. Each set has its own title, possibly leading the unwary to think the release contains new material. Kozena’s, for example, is called “Enchantment.” For tenor Placido Domingo, the marketers promise his fans “Truly Domingo.” DG has also brought forth a set of Beverly Sills excerpts, though not designated as part of the “Portrait” series, with the number of other fine artists featured acknowledged in the title: “Beverly Sills and Friends.”

Domingo’s career started around the same time as Sills’, but he still commands a top-rank position in the opera world, while she has been retired for some years. The cover of Domingo’s set features his handsome face, with the silver hair more than any lines on his face identifying his age. The Sills cover photo looks to come from the 1970s, with a blouse as full of ruffles as her hair is brilliant and towering. The freshness of the performances inside the two sets, however, prompts a different response.

Domingo has always been praised, and rightly so, for his impeccable musicianship and handsome

tone. He is not a tenor to sob, stretch out climaxes, or glory in the top notes (seldom easy for

him). The booklet essay maintains that his greatest contributions came in Verdi, and each of the

two discs starts with several selections from that composer. Though always tasteful and

committed, in none of the more familiar selections does Domingo offer a strong individual

reading. His Duke in “La donna è mobile” has little swagger. His Alfredo in the act two Traviata

aria lacks an impetuous edge to the passion expressed. The “Di quella pira” feels tame, and much

too slow (under Carlo Maria Giulini’s baton). Only in the Otello selections, from the

Myung-When Chung set, does Domingo bring forth a solid interpretation. The two Puccini

selections, “Donna non vidi mai” and “Nessun dorma,” boast the rewards of Domingo’s warm

middle voice, but the tight top compromises the effect. Domingo would have been better served

with selections from the Mehta La Fanciulla del West set, one of the tenor’s stronger performances.

Domingo has always been praised, and rightly so, for his impeccable musicianship and handsome

tone. He is not a tenor to sob, stretch out climaxes, or glory in the top notes (seldom easy for

him). The booklet essay maintains that his greatest contributions came in Verdi, and each of the

two discs starts with several selections from that composer. Though always tasteful and

committed, in none of the more familiar selections does Domingo offer a strong individual

reading. His Duke in “La donna è mobile” has little swagger. His Alfredo in the act two Traviata

aria lacks an impetuous edge to the passion expressed. The “Di quella pira” feels tame, and much

too slow (under Carlo Maria Giulini’s baton). Only in the Otello selections, from the

Myung-When Chung set, does Domingo bring forth a solid interpretation. The two Puccini

selections, “Donna non vidi mai” and “Nessun dorma,” boast the rewards of Domingo’s warm

middle voice, but the tight top compromises the effect. Domingo would have been better served

with selections from the Mehta La Fanciulla del West set, one of the tenor’s stronger performances.

Disc one ends, after an ardent “flower aria” from Carmen and a slice of the Kubelik Oberon, with Wagner, where Domingo’s handsome tone can pour out and his top is less often called upon.

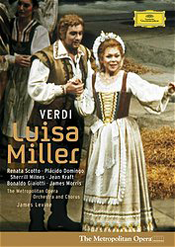

Disc two starts with some rarer Verdi, from the large DG set of a few years back covering all the major Verdi tenor roles. In this lesser-known material, Domingo’s firm grasp of the melodic line is much appreciated. Regrettably, the dramatic introduction to Luisa Miller’s “Quando la sere al placido” is not included. Ending the set are some rather bland selections from a disc of “spiritual”-themed music of a few years ago, and some much more enjoyable and idiomatic singing of songs and zarzuela selections.

The Sills set features large sections from her complete opera recordings, and ends with a wonderful potpourri of numbers with Charles Wadsworth accompanying her, from Schubert and Handel to Arne and Adam. By the end of the second disc, a more through and detailed “Portrait of the Artist” has been drawn than the Domingo set provides. In Manon and Lucia, Sills’s soprano has a wonderfully brilliant lightness, yet the dark edges of each character also come through . Then, in selections from her three Donizetti queens, she takes on a more dramatic thrust, while maintaining her control of florid passages. These longer excerpts, featuring such fine other singers as Shirley Verrett and Eileen Ferrell, provide time for a fuller view of the dimensions of Sills’ s art than Domingo can convey in his aria-intensive overview.

Disc two opens with Ms. Sills’s sensual Giulietta from Les Contes d’Hoffman and then offers her Baby Doe from Douglas Moore’s opera. Your reviewer is among those who find the music, and especially the libretto, unfortunately dated and old-fashioned, but Ms. Sills does sound impressively lovely in the “Willow song.”

The last half of the second disc is an uninterrupted stream of delights, with rare material, from baroque to early classical era. The style pre-dates the onset so-called “historically-informed performances,” but anyone who can resist the charm of Ms. Sills’s singing here is, well, over-informed. A lively aria from Lehar’s Der Zarewitsch closes the set.

Domingo might have been better served by a different set of selections, but DG has done wonderfully by Ms. Sills. For those who have had limited exposure to her achievements, Beverly Sills and Friends deserves a strong recommendation.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sills.png image_description=Beverly Sills and Friends product=yes product_title=Beverly Sills and FriendsWorks by Adam, Arne, Bellini, Bishop, Caldara, Donizetti, Handel, Lehár, Massenet, Moore, Offenbach, Schubert product_by=Beverly Sills and others product_id=Deutsche Grammophon 477 6304 [2CDs] price=$14.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=144785

Handel Singing Competition Final – London April 23rd

Year on year the competition’s status has grown and this was reflected last night in both the quality of the singing, and the quantity of audience there to listen – the place was packed with keen Handelians of all ages, music agents, directors and critics. Some sixty original young performers had started out on the audition and knock-out rounds, so the final six singing last night had made it through against considerable opposition and it showed. What was perhaps most interesting of all was perusing the contestant’s resumés and noting that two came from Australia, one from South Africa, one from Portugal and one from Eire.

As with all competitions, what the judges are looking for is not always what is appreciated most by the audience, but at least the London Handel one acknowledges this with both 1st and 2nd prizes and also an Audience Prize, given to the singer who gains the most votes in a quick-fire ballot taken immediately after the singing stops. Last night overall victory went to the only baritone singing, Derek Welton, the possessor of a fine, robust instrument who concentrated his fire on shorter oratorio and anthem pieces, with only one excerpt from an opera. His singing was focused and exact and technically very secure, his wider experience showing, even if he was rather wooden in his character portrayals. At the other end of the male vocal scale, and receiving the 2nd prize, was the countertenor Christopher Ainslie who conversely concentrated on Handel’s great arias for castrato from Serse, Orlando and Tamerlano. His rather elegantly “English” voice, although slightly covered at times, was complemented by a pleasing stage presence and flair for interpretation. For the ladies, it came as no surprise when the Audience Prize was bestowed on the charming Irish soprano, Anna Devin. Her strong interpretive skills were matched by a strong, secure technique and beautiful vocal tone and she shone in her two arias from Alcina and Giulio Cesare.

The losing competitors had nothing to be ashamed of – they all sang with credit and commitment and with great promise for the future: Gilliam Ramm, Joana Seara, sopranos and Julia Riley, mezzo-soprano. The first named had a big voice, perhaps lacking a little in Handelian style but impressive nevertheless, Seara from Portugal sang with delightful delicacy and precision, without too much power however, and Riley seemed to suffer a little from nerves and a rather odd choice of repertoire in her first items which hardly showed her voice off as they might. Her final aria from Ariodante showed glimpses of what she may be capable of in time.

As usual all the young singers were accompanied by the very supportive and elegant London Handel Orchestra, guided by Laurence Cummings.

© Sue Loder 2007

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Handel_singing_competition.png image_description=The Handel Singing Competition product=yes product_title=Handel Singing Competition Final – London23 April 2007

Kelly Kaduce sings Anna Karenina

And behind that wish is the tremendous impression that Kelly Kaduce, who sings the title role in Miami, has made on him.

“She’s such a great artist — a wonderful singer and a superb actress,” says Gierlach, whose signature roles include Mozart’s Figaro and Giovanni. “I wish that Tolstoi had come up with a an ending that would have let Anna and Vronsky work things out and stay together.” He feels that Kaduce, who will repeat the role when this co-production is on stage at the Opera Theatre of St. Louis this summer, makes a particularly strong and sympathetic figure of Anna — despite the events that lead to her tragic death. “As Kelly sings her, Anna is still the winner,” Gierlach says. “She makes clear that she is a woman of courage. “Anna wanted to be free and independent and she was willing to fight society in her desire to find love. She refused to accept the limits placed on her.”

Gierlach describes Kaduce as “an inspiring artist” and states that working with her on this premiere has been a fine experience. “I’m so happy to have been a part of this,” he says.

Less than a decade after winning the 1999 Metropolitan Opera auditions Kaduce has made an

unusually strong mark in the world of music theater and has brought distinction to a number of

world premieres. Most recently she sang Rosashorn in Ricky Ian Gordon’s “The Grapes of

Wrath” at Minnesota Opera, where she made this spoiled young member of John Steinbeck’s

Joad family wonderfully credible and gripping. Indeed, she made Rosashorn a major center of

attention in the four-hour work, tracing her development from selfish innocence to the insights

that come with her pregnancy and the desertion of her husband with heart-rending conviction.

(“Rosashorn” is, of course, a corruption of the biblical “Rose of Sharon.”)

Less than a decade after winning the 1999 Metropolitan Opera auditions Kaduce has made an

unusually strong mark in the world of music theater and has brought distinction to a number of

world premieres. Most recently she sang Rosashorn in Ricky Ian Gordon’s “The Grapes of

Wrath” at Minnesota Opera, where she made this spoiled young member of John Steinbeck’s

Joad family wonderfully credible and gripping. Indeed, she made Rosashorn a major center of

attention in the four-hour work, tracing her development from selfish innocence to the insights

that come with her pregnancy and the desertion of her husband with heart-rending conviction.

(“Rosashorn” is, of course, a corruption of the biblical “Rose of Sharon.”)

In Detroit Kaduce created the role of Caroline Gaines in Richard Danielpour’s “Margaret Garner,” a role she repeated with the Opera Company of Philadelphia. And in St. Louis she sang in title role in the American premiere of Michael Berkeley’s “Jane Eyre” and later this summer she appears at the Santa Fe Opera as Princess Lan in the world premiere of Tan Dun’s “Tea: A Mirror of Soul.” Her 2003 Santa Fe debut was also in a world premiere: Bright Sheng’s “Madame Moa,” in which she sang two roles — the Chinese Actress and ZhiZhen. And although the 2006 Florida staging celebrated the 50th anniversary of Carlyle Floyd’s “Susannah,” Karduce brought new depth to the title role at Orlando Opera.

It’s quite a track record for a woman who grew up in a Minnesota town of 1500, where opera was at most something on the radio. “I had no idea that you could make a living as a singer,” Kaduce said in an interview during rehearsals in Miami. “I enjoy the forests and the out-of-doors and I spent my first two years at St. Olaf as a biology major.” At that point someone heard her sing and suggested a change of majors.

“I had always sung,” says Kaduce, pointing out that her mother played the piano and served as a church organist. “I grew up listening to the top 40 and singing musical theater. “But when I started to sing classical repertoire, I discovered this incredible music I knew nothing about, music much more suited to my voice.” Kaduce only on-stage experience before leaving Minnesota for Boston University was a college “Bohème,” in which she sang not Mimi but Musetta.

More crucial was a performance of “Pelléas et Mélisande” by Minnesota Opera that she had seen in her sophomore year. “That’s when I fell in love with opera,” she says. “It was clear to me then that this was the profession for me. The performance further brought out Kaduce’s affinity for French opera, soon confirmed by her first appearances in “Faust” and “Thaïs,” which she sang while studying with Penelope Bitzas in the Opera Institute at Boston University.

Butterfly and Mimi followed, and critics crowned Kaduce with laurels for both roles. “Kelly Kaduce’s Madama Butterfly is nothing short of breathtaking,” a Boston critic wrote of her debut as Puccini’s gentle Japanese bride. “Some Madamas are heart-warming, others are heart-rending, and Kaduce’s is the best of both.” And about her portrayal of Cio-Cio San’s death another reviewer wrote: “With Kaduce, Butterfly’s suicide was not the cowardly capitulation of a hapless victim, but the act of someone who every step of the way has looked fate straight in the eye with dignity and acceptance.”

Karduce has no particular explanation for her success in new opera beyond the fact that at the outset of her career she “didn’t want to say ‘no’” when offered a role. “But even in college I was fascinated by new works,” she says, “and once I was involved in a premiere I enjoyed the challenge.” She speaks of Anna, for example, as “a blank canvas,” and it’s up to her to fill it with life. “I read the novel again and studied the background and history of it,” she says, “and then I put all that aside and turned to the libretto. “It’s exciting that in a new work I’m largely on my own — there are no recordings to listen to and no videos to watch.” Kaduce relishes getting down to work with the composer, director, conductor and fellow members of the cast.

The weight of the Florida premiere has been augmented by the April 7 death of Colin Graham, a major force in American opera for a quarter century. Graham extracted the libretto of “Anna Karenina” from Tolstoi’s novel and was slated to serve as stage director in Miami. “We had been good friends for the past five years,” Kaduce says. “And — happily — I was still able to discuss Anna with him.” It’s an opera, she says, in which one really needs a director because of the complexity of the relationships within it.

Critically ill as the FGO premiere went into rehearsal, Graham’s death was not a surprise; assistant director Mark Streshinsky was already deeply involved in “Anna” and ready to take over. “Colin was my teacher and I felt well prepared to step in,” he says. “And I’m really excited about the opera.” A major source of that excitement is working with Kaduce “She’s simply perfect as Anna,” Streshinsky says. “She’s a real artist and she knows the novel so well. “And she has the bearing of a real Anna.”

Kaduce describes her recipe for success as singing roles in which she “can produce a maximum of sound with a minimum of effort.” And although she has been asked to sing Salome, she feels that — just into her 30s — she is not ready to move into Strauss. Overly busy with opera, Kaduce will sing her first recital in five years at the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival this summer. “This is a very tough business,” teacher Penelope Bitzas told a Boston writer in an interview about Kaduce. “A singer has to keep going in the face of disappointments, no matter what. And there’s the element of luck and of being in the right place at the right time. “Kelly is a very hard worker. She’s very focused and mature. Her voice is this beautiful, round, dark, yummy sound. She has a way about her when she sings — she radiates. “That’s something you can’t teach. Singers either have it or they don’t.”

Wes Blomster

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kaduce.png image_description=Kelly Kaduce as Anna Karenina (Photo: Deborah Gray Mitchell) product=yes product_title=Above: Kelly Kaduce as Anna Karenina(Photo: Deborah Gray Mitchell)

April 23, 2007

Wozzeck at San Diego Opera

In the week after the horrific crime at Virginia Tech, the question strengthened this great but harsh masterpiece’s claim on the attention of an opera-going public still hesitant to expose itself to the work, over 80 years past its premiere. San Diego Opera General Director Ian Campbell’s greeting to his company’s patrons in the program almost begged for their indulgence: Wozzeck “is ‘not’ Aida or Madama Butterfly,” he helpfully explained, but a work that “took opera in new directions.”

During the performance Sunday, a few audience members took the “old” direction toward the exits during the scene changes, creeping out as Wozzeck, apparently, creeped them out. The majority stayed to extend warm appreciation to the hard-working cast at the opera’s conclusion — a rather abrupt one, with the last note from the orchestra beating the curtain down, a true rarity.

Campbell turned to a theater director new to opera, as the news-making Peter Gelb of the

Metropolitan Opera has done. San Diego has been the home base for Des McAnuff, who has

helmed Tony-award winning musicals from Big River in 1985 to Jersey Boys in 2006. With

scenic designer Robert Brill, McAnuff created an eerie, tense Wozzeck, without the slightest hint

of any showbiz glitter. The cast, in Catherine Zuber’s time-appropriate costumes, live in a cold,

clinical world: the uni-set most resembles a hospital amphitheater for clinical examinations, with

metallic scaffolding forming tiers on the outside, and a huge, tilting disc of lights hanging over

the empty center. Unfortunately, the designers decided this should be a revolving set, and the

turntable apparatus made an unacceptable amount of noise, especially in the scene where Chris

Merritt’s Captain noted how quiet the evening was.

Campbell turned to a theater director new to opera, as the news-making Peter Gelb of the

Metropolitan Opera has done. San Diego has been the home base for Des McAnuff, who has

helmed Tony-award winning musicals from Big River in 1985 to Jersey Boys in 2006. With

scenic designer Robert Brill, McAnuff created an eerie, tense Wozzeck, without the slightest hint

of any showbiz glitter. The cast, in Catherine Zuber’s time-appropriate costumes, live in a cold,

clinical world: the uni-set most resembles a hospital amphitheater for clinical examinations, with

metallic scaffolding forming tiers on the outside, and a huge, tilting disc of lights hanging over

the empty center. Unfortunately, the designers decided this should be a revolving set, and the

turntable apparatus made an unacceptable amount of noise, especially in the scene where Chris

Merritt’s Captain noted how quiet the evening was.

The “examination room” concept makes sense as a metaphor for the work’s detailed analysis of Wozzeck’s breakdown, but it also serves to distance the audience from the poor soldier’s plight. If everyone is living in the same cruel confines, why is he the only one who descends into madness? In the interludes between scene changes, film (designed by Dustin O’Neill) filled the stage-covering scrim. Some of the images brushed up against cliche, such as time-elapsed shots of dark clouds streaming through a gray sky. For the most part, the dead-eyed visage of Franz Hawlata’s Wozzeck stared out. His unchanging expression — or lack of same — served to work against a sense of increasing anxiety to approaching doom.

So with this, his first attempt at an opera, McAnuff may have felt hesitant to bring the full-force of his skills to the production. His direction, while detailed and well-structured, provided no fresh perspectives. Merritt’s Captain screamed and strutted like a borderline psychotic himself. Dean Peterson’s doctor, on the other hand, seemed a pallid figure, offering tame diet advice after a perfunctory prostate examination. Jay Hunter Morris’s Drum Major did capture both the masculine appeal and brutality of his character.

As Marie, Nina Warren truly cut a pathetic figure of desperation, both in the face of her own lust

and her partner’s advancing paranoia. Her top rang out with a cutting edge that made your

reviewer interested in hearing her Salome, or even Elektra.

As Marie, Nina Warren truly cut a pathetic figure of desperation, both in the face of her own lust

and her partner’s advancing paranoia. Her top rang out with a cutting edge that made your

reviewer interested in hearing her Salome, or even Elektra.

At the center stood the forlorn figure of Franz Hawlata, pale and haunted, the lower range of his voice seeming to echo in the emptiness of the character. Wozzeck’s demise, however, came with the production’s arguable misfire, with Hawlata, instead of descending into water, having to strap himself onto a disc that mirrored the lights above. The disc then rose and tilted as a scrim descended, with film of a watery surface projected on it. The theatrical effect deadened the dramatic intention.

By far the greatest strength of the performance came from the orchestra under the leadership of Karen Keltner. Last heard by your reviewer leading the musicians in the very different score of Bizet’s Pearlfishers (!), Ms. Keltner caught the grinding dissonance and also the many moments of spectral beauty in Berg’s score.

Though by no means a “missed opportunity,” after this only intermittently successful Wozzeck McAnuff, if he continues to direct opera, should be confident enough to bring more daring and personal insight into his work. In the meantime, almost as a reward for their attendance at this still-challenging work, the SDO patrons can look forward to Mozart’s Nozze di Figaro, closing the 2007 season with familiar melodies and a starry cast. And perhaps after Wozzeck, the pain underneath the laughter in Da Ponte’s libretto will seep through.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Wozzeck03.png image_description=German bass Franz Hawlata sings the title role of Wozzeck in San Diego Opera’s production of Wozzeck, directed by Des McAnuff. Photo © Cory Weaver product=yes product_title=Alban Berg: WozzeckSan Diego Opera, 22 April 2007 product_by=All photos courtesy of San Diego Opera

Giulio Cesare at Barbican, London

Tim Ashley [Guardian, 23 April 2007]

Tim Ashley [Guardian, 23 April 2007]

Much has already been written about the current Handel glut in our opera houses and concert halls. The problem lies, perhaps, not in quantity but in quality. The growing popularity of his music, particularly the operas, has resulted in a proliferation of indifferent performances.

Shrieks and screams over orchestra

Ken Winters [Globe and Mail, 23 April 2007]

Ken Winters [Globe and Mail, 23 April 2007]

Salome and Elektra, the two operas in which Richard Strauss made German-Expressionist, very bloody shovels out of merely lurid spades from the Bible and Sophocles, staked out a path that Strauss thereafter did not take. Perhaps he took seriously the noted critic Ernest Newman's comment that Elektra was "abominably ugly."

Stiffelio, Royal Opera House, London

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 23 April 2007]

By Andrew Clark [Financial Times, 23 April 2007]

Sex, sects, adultery and divorce: 21st- century soap opera? No, 19th-century grand opera. We like to think we’re liberated in the way we confront the great moral and social taboos, but Verdi was there before us.

A Triply Superb ‘Il Trittico'

BY JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 23 April 2007]

BY JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 23 April 2007]

Friday night was a fantastic night at the Metropolitan Opera. Why? On the stage was Puccini's superb triple bill, "Il Trittico." It appeared in a splendid new production by Jack O'Brien. In the cast, or casts, were some of our best singers, and most of them were in top form. James Levine was in the pit, and he, too, was in top form — which is some form. And the Met orchestra played sensationally well.

April 22, 2007

Satyagraha at ENO

Assembled from selected phrases of the Baghavada-Gita by librettist Constance de Jong, the opera was performed here entirely in unsurtitled Sanskrit, contrary to ENO’s “everything in English” policy. Presumably the thinking was that if a native English speaker chooses to write an opera in the language of the subject matter, then keeping the original language is key to preserving the integrity of the piece. In fact the entire libretto consists of just eighteen paragraphs of text, so along with the undulating repetitiveness of the score, each scene seems to hang entranced in mid-air. The work is, after all, a sequence of vast portraits of the promotion of passivity, rather than a living drama. A synopsis was supplied in the programme; however it provided context rather than actual plot.

The giant curved structure of the set was used to represent something between a holy book and a political memoir, by means of projected text and textual ornament which turned it from a corrugated-iron wall into an illuminated page. To this and the blank canvas of Glass’s music, the performance-art group Improbable brought their stunning brand of performance art, stilt-walking, aerobatics and puppetry. Scattered news pages and swathes of tape were formed into giant moving creatures, gods and political figures, then evaporated into air just as quickly. Hindu gods fought one another; giant grotesque figures walked amongst the buildings of a more modern world. And still the musical inertia continued.

Even within its stylistic context (that is to say, assuming that as an audience member one can absorb such a lengthy musical work where very little happens) the piece itself has structural failings, most noticeably the hole created by an over-long instrumental interlude preceding Gandhi’s Prayer in the third act.

The singing was of an exceptional standard almost throughout. Besides Alan Oke’s sincere, other-worldly tenor in the focal role of Gandhi, a large share of the credit should be given to conductor Johannes Debus and to ENO’s terrific chorus, particularly the men, who exhibited impressive rhythmic control as Act 2’s collective voice of complacent greed. Most of the principal cast were company regulars, although in her ENO debut as Miss Schlesen, the Greek-Australian soprano Elena Xanthoudakis made a hugely positive impression, with a secure purity to her meaty top notes. Indeed there were few vocal weaknesses — Jean Rigby’s Mrs Alexander had problems making herself audible, and Janis Kelly’s Mrs Naidoo experienced some intonation problems in her duet with Anne-Marie Gibbons’ Kasturbai.

This staging is a co-production with the Met, where it will be presented this time next year – and like ENO’s last Met collaboration (Anthony Minghella’s cinematically beautiful Madama Butterfly in 2005) is a visually breathtaking piece of theatre. Glass’s score, on the other hand, is more of an issue. It certainly creates a powerful atmosphere — but at over three hours of scales and repeated phrases, and with no character interaction or dialogue, can it even be thought of as an opera?

Ruth Elleson ©2007

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mahatma-Gandhi.png image_description=Mahatma Gandhi product=yes product_title=Philip Glass: SatyagrahaEnglish National Opera, 13 April 2007 product_by=Click here for Satyagraha mini-site.

April 21, 2007

VERDI: Nabucco (Nabucodonosor)

Music composed by Giuseppe Verdi. Libretto by Temistocle Solera after Nabuccodonosor, a ballet by Antonio Cortesi, and Nabuchodonosor, a play by Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois and Francis Cornu.

First Performance: 9 March 1842, Teatro alla Scala, Milan.

| Principal Characters: | |

|---|---|

| Nabucodonosor, King of Babylon | Baritone |

| Ismaele, nephew of Sedecia, King of Jerusalem | Tenor |

| Zaccaria, High Priest of the Hebrews | Bass |

| Abigaille, a slave | Soprano |

| Fenena, daughter of Nabucodonosor | Soprano |

| The High Priest of Baal | Bass |

| Abdallo, elderly officer of the King of Babylon | Tenor |

| Anna, Zaccaria’s sister | Soprano |

Synopsis:

Part I

Nabucco, King of Babylon, has attacked the Israelites who, gathered in the temple of Solomon, pray for the salvation of Israel. The High Priest encourages them to have faith in their God, and says that he has a valuable hostage, Fenena, the daughter of Nabucco, Ismaele arrives, the nephew of the King of Jerusalem, to whom Zaccaria entrusts Fenena when he learns that Nabucco is making a furious entry into the city. Ismaele and Fenena, in love with each other, attempt to flee, but Abigaille — a slave believed to be Nabucco’s first daughter — bursts into the temple at the head of a band of Babylonian warriors disguised as Israelites. Abigaille, who unrequitedly loves Ismaele, accuses him of betraying his country but offers to save him if he will return her love. Nabucco now enters the temple but is confronted by Zaccaria, who threatens to kill Fenena if he profanes the sanctuary. As the High Priest is about to stab her, Ismaele disarms him: Fenena throws herself into the arms of Nabucco, who orders the destruction of the temple in revenge.

Part II

Having returned to Babylon, Abigaille learns from a document taken from Nabucco that she is a slave, and for this reason he has appointed Fenena regent in his absence. Furious with Nabucco and Fenena, who has been converted to the God of Israel, she attempts to wrest the crown from her but the King arrives and, snatching the crown from Abigaille and repudiating both the God of Babylon and the God of the Israelites, proclaims himself God. He is immediately struck down by a thunderbolt, and dementedly invokes Fenena’s aid while Abigaille picks up the crown.

Part III

Abigaille, having seized the throne, orders the death of all the Israelites. Nabucco enters in ragged clothing, claiming back the throne which Abigaille says she has occupied for the good of Baal, as he is deranged. She forces him to sign the Israelites’ death-warrant, but when Nabucco realizes that he has thus condemned Fenena he wants to retract, Abigaille is obdurate and has him led off to prison. On the banks of the Euphrates the Israelites, in chains, lament their fate.

Part IV

From prison Nabucco sees Fenena being dragged to her death and desperately begs forgiveness from the God of the Israelites. Restored to sanity, he escapes with a band of faithful soldiers and saves his daughter. The idol of Baal falls and shatters, and Nabucco extols the glory of Jehovah. Abigaille has taken poison but, on the point of death, she begs Fenena’s forgiveness and blesses her love for Ismaele, imploring God’s mercy. Nabucco is hailed by Zaccaria as the king of kings.

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Nebuchadnezzar_medium.png image_description=Nebuchadnezzar kills the children of the King Zedekiah by Gustave Doré (1866) [Source: 2 Kings 25: 1-7] audio=yes first_audio_name=Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco (Nabucodonosor)Windows Media Player first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Nabucco1.wax second_audio_name=Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco (Nabucodonosor)

WinAMP or VLC second_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Nabucco1.m3u product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco (Nabucodonosor) product_by=Abdallo: Luciano della Pergola

Abigaille: Maria Callas

Anna: Silvana Tenti

Fenena: Amalia Pini

The High Priest: Ighino Riccò

Ismaele: Gino Sinimberghi

Nabucco: Gino Bechi

Zaccaria: Luciano Neroni

Conductor: Vittorio Gui

Orchestra and Chorus of Teatro San Carlo, Napoli

Live performance, 20 December 1949, Naples

April 20, 2007

Da Corneto ready for 'cursed' opera

BY MIKE MITCHELL [Naperville Sun, 20 April 2007]

BY MIKE MITCHELL [Naperville Sun, 20 April 2007]

In 1960, American baritone Leonard Warren died on stage during a performance of Verdi's epic "La Forza del Destino." For years, many artists considered the opera cursed, in terms of vocal demands as well as its melodramatic plot.

Beauty Across the Board

BY JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 20 April 2007]

BY JAY NORDLINGER [NY Sun, 20 April 2007]

The Finnish soprano Karita Mattila is a sensation on the operatic stage: as Salome, to name only one role. But she is also a sensation on the recital stage, as she proved at Carnegie Hall four years ago. That was a dazzling, foot-stomping event. And she was good on Wednesday night, too, in the same hall.

Met's `Trittico' . . .

By Stephen West [Bloomberg.com, 20 April 2007]

By Stephen West [Bloomberg.com, 20 April 2007]

April 20 (Bloomberg) -- Jack O'Brien, the director of ``Hairspray,'' makes his Metropolitan Opera debut tonight staging Puccini's ``Il Trittico,'' a trio of short operas with good tunes. ``Il Tabarro'' culminates in a murder on a Parisian tugboat; ``Suor Angelica'' features a suicidal nun; in ``Gianni Schicchi,'' a comedy based on Dante, the wily title character impersonates a dead person and inherits a fortune.

The Rake’s Progress, La Monnaie, Brussels

By Francis Carlin [Financial Times, 19 April 2007]

By Francis Carlin [Financial Times, 19 April 2007]

The programme book, an imitation of Life magazine, sets the tone. Robert Lepage’s new production transposes Hogarth’s story to America in the 1950s when Stravinsky and librettists Auden and Kalman wrote the work. Tom is James Dean and Trulove is Rock Hudson as in the film Giant. The fleshpot is Hollywood and the satire is directed at vacuous TV culture.

April 19, 2007

PENDERECKI: Symphony no. 7

This oratorio-like work was commissioned to celebrate the third millennium of Jerusalem, and in approaching the work, Penderecki made some overt connections to the city. The traditional seven gates of the city in the title are reflected in the seven-movement structure of the work and, as indicated in the notes that accompany the recording, Penderecki used the figure seven in various ways throughout the work. By using texts from the Old Testament that call to mind various aspects of the city, not just as a place, but a site laden that anchors spiritual associations. (The texts for the movements are organized as set forth in the table below.)

A close reading of the text shows that Penderecki shaped the verbal content carefully. By selecting verses to be sung, he gave the text focus and clarity so that the piece could contain the specific phrases that he wanted to use, rather than carry along verses for the sake of completeness. Taken together, the verses for the first movement are, for example, essentially a new text, albeit one redolent of the psalter. With other movements, though, the choices are more complicated, and suggest an internal dialogue that places prophetic statements alongside the adulatory — or sometimes admonishing — ones from the psalms. With the last movement, to cite another example, it is possible to see a development of textual ideas, as Penderecki combines verses from three prophetic books, and then returns to the psalms, eventually bringing back the verse with which the Symphony opened. This suggests a level of composition that bears further consideration for the structural organization that is linked to the musical structure of the work.

As to the style of the work, Penderecki’s Symphony no. 7 is relatively conservative, with the nuances of texture and timbre having given way to some of the innovations associated with his earlier pieces. To put the Symphony in perspective, the comments of Adrian Thomas offer a point of departure. In discussing some of Penderecki’s later symphonies, Thomas suggests that: “Given that Penderecki’s focus is habitually on line, timbre, tempo and dynamics, his concert music of the past quarter century relies on plain-speaking rhetoric, on readily absorbed intervallic and rhythmic repetitions, and on the reinterpretation of models drawn from major symphonic composers of the past….” (Adrian Thomas, Polish Music since Szymanowski [Cambridge University Press, 2005] p. 251). This précis fits this work well, as it captures the stylistic elements that operate in this work. Like the symphoniae sacrae of seventeenth-century composers like Heinrich Schütz, Penderecki used voices and instruments to present concerted settings of texts from the Bible. The scope of Penderecki’s effort in his Seventh Symphony differs because of the multi-movement structure he used to create this musical reflection of the city of Jerusalem. In finding such a locus for his musical structure, Penderecki echoes, however distantly, his earlier Threnody for Victims of Hiroshima, another work in which the evocation of a city results in a work that has universal resonance.

This work also belongs to the choral symphony of the nineteenth century, reminiscent in a sense of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony for its use of voices throughout the work. Similarly, Mahler’s efforts to bring together different texts — in the case of the Eighth Symphony, the Latin hymn “Veni creator spiritus” and the final scene from the second part of Goethe’s Faust, Penderecki combined verses from various psalms, as well as different parts of the Old Testament. Psalms and prophetic texts are brought together in this Jerusalem-inspired work which, in this sense, reflects those aspects of the old city as a place of worship and a locus of prophetic vision. In this sense, it is a return to those seventeenth-century composers, whose works use large forces along with concertato sonorities to prsent biblical texts, but conceived along much larger lines.

While it is possible to find such lines of thought in the work, Penderecki’s Seventh Symphony also belongs to thecomposer’s other works in this genre. Composed over a quarter century, Penderecki’s symphonies differ from each other in ways reminiscent of Mahler of Shostakovich and, as with those composers, also reflect some aspects of Penderecki’s other music. With its use of Latin, it resembles the composer’s St. Luke Passion with a language that at once offers a lingual neutrality through a ritualistic, language that is no longer used in the vernacular.

Regarding the musical language, though, Penderecki uses blocks of sound that convey a sense of the solidity of his structure. The opening gesture itself presents an intensive mass on which he builds what becomes a refrain for the movement. The opening sounds of the chorus punctuated with percussion and intersected with low-brass figures is an impressive, almost ritualistic gesture that introduces the first movement. The tutti orchestral cadences further define the vocal phrases of this massively conceived piece, which offers a paean in music that transcends the artificial boundaries of religion. Yet as the text of the verses of the psalm occur, the subtler presentation with solo voices becomes a textural foil for the larger forces that occur in the refrain.With the second movement, Penderecki draws on the orchestra for gestures that set a different tone and at once suggests the Penderecki’s style in other, similar pieces for that combine orchestral forces with choral ones. At times the textures contain some distantly related sounds that, in turn, suggest musical space that reinforces the distance connoted in the text “If I forget you, Jerusalem.” As with the first movement, the second is effective in presenting its text in a unique way. In fact, each of the movements is distinct enough to stand on its own merits, yet when conceived together, form a cohesive symphonic structure.

The work is in Latin, with the sixth movement, the most dramatic of the entire work, in Hebrew, with the text from Ezekiel presented by a speaker. In this recording, Boris Carmeli, a voice otherwise associated with opera, is effective in presenting the text with aplomb and clear enunciation. This piece moves away from the choral forces, to create a different kind of sound through the combination of spoken text with the pointillistic orchestral texture that supports it. While the work is well served with the solo voices that occur in various movements, the use of spoken work calls attention to the text, which demands notice because of the chosen mode of presentation that takes the words outside the bounds of singing. As such, the composer demands attention to the text, and thus forces this piece to stand apart from the other movements. At times unsettling, the movement is an effective setting of a challenging text that holds a crucial place within the overall framework of the Symphony.

With several recordings of this work available, audiences have the rare opportunity to select between various performances. This reading by Antoni Wit has much to offer through its highly polished and finely shaped choral sonorities, and equally adept instrumental forces. Naxos has made much of Penderecki’s music available through recordings that are at once reliable and affordable, and the addition of this title to its offerings should bring this powerful work to a wide, international audience. In this work the twentieth-century symphony, which has been a mode of expression for Polish modernists, takes on new formal dimensions in one of Penderecki’s fine recent pieces.

James L. Zychowicz

| Mvt | Title | Texts | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Magnus Dominus et laudabilis nimis in civitate | Great is the Lord, and to be praised | Psalm 47 (48):1 Psalm 95 (96):1-3 Psalm 47 (48):1 Psalm 4 (487:13 Psalm 47 (48):1 |

| 2. | Si oblitus fuero tui, Ierusalem | If I forget you, Jerusalem | Psalm 136 (137):5 |

| 3. | De profundis clamavi ad te, Domine | Out of the depths, have I called you, O Lord | Psalm 129 (130): 1-5 |

| 4. | Si oblitus fuero tui, Ierusalem | If I forget you, Jerusalem | Psalm 136 (137):5 Isaiah 26:2 Isaiah 52:1 Psalm 136 (137):5 |

| 5. | Lauda, Ierusalem, Dominum | Praise the Lord, Jerusalem | Psalm 147:12-14 |

| 6. | Hajetà alai jad adonài, | The hand of the Lord was upon me | Ezekiel 37: 1-10 |

| 7. | Haec dicit Dominus | Thus says the Lord | Jeremiah 21:8 Daniel 7:13 Isaiah 59:19 Isaiah 60:1-2 Psalm 47 (48):1 Isaiah 60:11 Psalm 95 (96):1; 2-3 Psalm 47 (48):1 Psalm 47(48):13 Psalm 47(48):1 Psalm 47(48):13 |

(Full text and translation available here.) product_id=Naxos 8.557766 [CD] price=$7.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=9281&name_role1=1&comp_id=89429&bcorder=15&label_id=19

April 18, 2007

Drama at Vienna opera: Who will be its new leader?

By Mark Landler [International Herald Tribune, 18 April 2007]

By Mark Landler [International Herald Tribune, 18 April 2007]

VIENNA: Alfred Gusenbauer vividly recalls his earliest nights at the opera. As a son of working-class parents, who came to Vienna from the provinces to study, he spent precious shillings to stand at the rear of the horseshoe-shaped auditorium in the Vienna opera house.

April 16, 2007

MAHLER: Des Knaben Wunderhorn

In addition to the song cycles entitled Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, Kindertotenlieder, and the symphony-song cycle Das Lied von der Erde, Mahler’s settings from Des Knaben Wunderhorn remain a central part of his musical legacy, since the are connected directly to the composer's symphonies. As some of Mahler's best-known music, the songs are not only familiar, but also convey their meaning directly to the listen. More importantly, some recordings, like this one, capture the spirit of the music. The fine attention to detail, including orchestration, tempo, and balance, earmark the approach that Philippe Herreweghe took in these performances of the selection of Mahler’s settings from the anthology Des Knaben Wunderhorn.

The Wunderhorn settings encompass about half of Mahler’s Lieder, with the ones he composed in the 1880s for voice and piano. Yet with the Wunderhorn songs that he composed in the 1890s, Mahler not only used piano accompaniment, but also scored the songs for voice and orchestra. Of the orchestral Wunderhorn-Lieder includes twelve settings, and Mahler composed two later songs from the same anthology several years later, “Revelge” and “Der Tamboursg’sell.” Several of the songs are also found in his symphonies, including “Urlicht” from the Second and “Es sungen drei Engel” from the Third, and in recent years “Das himmlische Leben” from the Fourth Symphony has been performed along with others songs, instead of in the symphonic context Mahler created for it.

For this recording, Herreweghe chose fourteen settings, which comprise a fine representation of this part of Mahler’s oeuvre. The singers involved are the mezzo soprano Sarah Connolly and the baritone Dietrich Henschel, who divide the pieces almost evenly between them. Since Mahler created settings for vocal ranges, such as high or low voices, rather than designating vocal types, it is not possible to distinguish between songs for male or female voice. Some of the songs lend themselves to this, while others have associations with a gender as a result of the existing performing tradition. Thus, it is customary to hear a female voice sing “Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt,” but not necessarily the only way to do so. In Herreweghe’s recording, Henschel performs this song, one that some male singers do not attempt. Yet with “Wer hat dies Liedlein erdacht?!”, a song with similar melismatic passages, women often perform it, as Connolly does in this recording.

Elsewhere, the texts of some of the songs are constructed as dialogues between lovers that some conductors have divided between two singers. In a respected – some would say classic – recording of these songs by George Szell (conducting the London Symphony Orchestra), a dialogue song, like “Lied der Verfolgten im Turm” is shared by Elizabeth Schwarzkopf and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, with each singer alternating by gender. There is no indication in Mahler’s scores for a second singer, and Herreweghe does not use this practice on this recording. (Henschel was given “Lied der Verfolgten im Turm.”) The literal application of “him” and “her” (“er” and “sie,” as sometimes rendered in the anthology Des Knaben Wunderhorn) to specific voices is not necessary, and talented singers, like those involved with this recording, can use their voices to convey the meaning of the text.

Beyond these considerations, one of the remarkable features of this recording is the effective performance and recording of the accompaniments. While a number of fine performances are available on CD, this particular one stands out for the nuances that emerge readily and consistently in this set. The motum perpetuum figuration at the beginning of “Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt” is subtle, as it helps to set up the various other figures that occur later in the song, including the sometimes dry timpani strokes that are entirely appropriate to the piece. Likewise, the brass execute their parts without overpowering the singer or overbalancing the vocal line. A similar balance in the brass occurs in “Trost in Unglück,” where those instruments must support the voice without covering it. Yet the prominent brass at the conclusion of “Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen” are appropriate, especially when the suggestion of the “Bruder Martin” theme used in the penultimate movement of the First Symphony emerges clearly. In all of this, the fine ensemble that characterizes some of Herreweghe’s approach to other composers serves Mahler’s music well. The fresh and full sound that emerges in each of the songs is a welcome addition to the discography. While individuals may have recordings they prefer for the singers involved, this is one of those instances where the accompaniment serves the orchestral Lieder in ways that other recordings sometimes fall short.

Yet the voices are not without interest, as Connolly and Henschel offer their interpretations of these familiar pieces. To hear “Das himmlische Leben” outside the Fourth Symphony is a bit jarring for those who know the latter work. Only recently has this song been included with the works that Mahler designated as Wunderhorn Lieder, and such presentation suggests the other context of the song, the set of Humoresken in which Mahler at one time included the song soon it. While it properly belongs to the work in which the composer left it, his Fourth Symphony, since its presentation there is the culmination of various thematic links serve to introduce the song in the three movements that precede it. When performed with other orchestral songs, the listener does not have the benefit of such thematic links, and so it must stand on its own merits. Nevertheless, Herreweghe’s tempos are convincing, and most of all, the sometimes full accompaniment is never strident or out of place. At the same time Connolly demonstrates a sensitive approach to a song that resists being oversung, that is, overly interpreted. She is effective in allowing the vocal line to emerge without affectation, and the result is quite satisfying.

Henschel also offers some fine performances. He has taken on some of Mahler’s longer Wunderhorn Lieder, like “Der Tamboursg’sell” and “Revelge,” and as demanding as those pieces are, he demonstrates a fine sense of Mahler’s style in some of the shorter songs, like “Lob des hohen Verstandes.” In the latter, he works well with Herreweghe in conveying the sense of irony that makes the song memorable.

Overall, though, it is not one voice over another that comes across as meriting attention, nor should it be that way. The orchestra emerges as a critical element of this recording, since the ensemble and its interactions create some vibrant performances of these songs. At its head, though, is Herreweghe, who brings a fine sense of style and musicianship to Mahler’s orchestral Lieder. It is a recording that stands well besides some of the familiar and respected ones in the discography of Mahler’s music.

James Zychowicz

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Wunderhorn.png image_description=Gustav Mahler: Des Knaben Wunderhorn product=yes product_title=Gustav Mahler: Des Knaben Wunderhorn product_by=Sarah Connelly, mezzo soprano, Dietrich Henschel, baritone, Orchestre des Champs-Élysées, Philippe Herreweghe (cond.) product_id=Harmonia Mundi HMC901920 [CD] price=$18.99 product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Drilldown?name_id1=7537&name_role1=1&comp_id=19725&genre=134&bcorder=195&name_id=56083&name_role=3‘Giulio Cesare': Et Tu, New Met?

By Jay Nordlinger [NY Sun, 16 April 2007]

By Jay Nordlinger [NY Sun, 16 April 2007]

Handel's "Giulio Cesare," or "Julius Caesar," is now playing at the Metropolitan Opera. And I like to describe it as a three-hour series of highlights. Handel gives you one hit after another, one immortal aria or duet after another. The inspiration never quits. In this, the opera is not unlike "Messiah." "Julius Caesar" is one of the most awesome bursts of creativity in music.

Pushkin/Prokofiev 'Godunov' finally realized

By David Patrick Stearns [Philidelphia Inquirer, 16 April 2007]

PRINCETON - Academia is the best home for the impossible. Such was the task at hand for the provocative, extravagant Princeton University-produced Boris Godunov - not the famous opera, but the Alexander Pushkin play as it might have been rendered by legendary director Vsevolod Meyerhold with music by Sergei Prokofiev.

Inventive staging, skilled cast bring 1836 drama to life

By Anne Marie Welsh [San Diego Union-Tribune, 16 April 2007]

By Anne Marie Welsh [San Diego Union-Tribune, 16 April 2007]

Eighty-two years is a long time to wait for the work that launched 20th-century music drama. The wait ended Saturday – and a door to its future may have opened, too – with the San Diego Opera's first production of Alban Berg's “Wozzeck” (1925) in an innovative, fluent, surprisingly somber staging directed by the Tony-winning director emeritus of La Jolla Playhouse, Des McAnuff.

In search of a distant sound

A composer's opera finally makes its arrival in America

A composer's opera finally makes its arrival in America

By Jeremy Eichler [15 April 2007, Boston Globe]

This afternoon at New York's Lincoln Center, the American Symphony Orchestra will perform an opera by Franz Schreker titled "Der Ferne Klang" or "The Distant Sound." It is, astonishingly, the first professional performance of any complete Schreker opera in North America. And herein lies a strange story, one of the great disappearing acts of modern music history.

City Opera Presents La Donna del Lago

Although the New York Times regarded the straight-forward plot as purely conventional we experienced the adaptation of Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake as somewhat unusual opera seria largely because the ending was happy, the king did not get the girl, and the only death occurred off-stage. Briefly, the plot consists of three men who each love Elena (the title character): Rodrigo, who has been promised her hand in marriage by her father; Uberto, the king of Scotland in disguise (a surprise to us all at the very end); and Malcolm, a handsome young man with few credentials to recommend him to her father other than the deep love he and Elena share.

La Donna has grown in popularity lately due to the diligence of musicologist Philip Gossett, who worked with Marilyn Horne in reviving Semiramide. La Donna also has a pants role—Elena’s young lover Malcolm is cast as a mezzo-soprano—and like Semiramide, it is the soprano/mezzo-soprano love duets that offer the most musically sensual moments.

Laura Vlasak Nolen as Malcolm stirred what was otherwise a somewhat sleepy matinee audience on Saturday, March 24, rousing them to cheers with her first-act aria, an electric out-pouring of love for the absent Elena. Nolen’s duets with Alexandrina Pendatchanska as Elena were also cause for much applause.

Pendatchanska’s voice and training were well-suited to the bel canto role of Elena, but she was at times hard to hear, possibly because the orchestra was overpowering her extremely florid and delicate sound. The two high tenors, characteristic of Rossini but a rare find nowadays, were also impressive. Robert MacPherson as Rodrigo was a very commanding presence, if somewhat inconsistent; we particularly were impressed with his energy in his first aria. The role of Uberto was ably filled by tenor Barry Banks who has a close performing relationship with Pendatchanska. Elena’s controlling father Douglas was performed by Daniel Mobbs.

The orchestra also performed admirably. The musicians handled the challenges of Rossini well, keeping the scales clean and the touch light. The woodwinds are to be especially commended for their solos in the overture. Too, offstage horns heralding the onset of war created some of the greatest spatial effects of the opera.

The set and costumes were designed by David Zinn, who characteristically employed lots of brick in his set design. The overall feeling was somewhat claustrophobic, especially in the scene inside Elena’s home where the wings moved inward and the towering walls reached the fly. Still, you must admire the man who tries to portray a lake with a wall of bricks. The uncomfortable effect was heightened by the presence of numerous stiff-looking chairs that were toted about the stage by stern women dressed in black. One other moment was particularly unfortunate in large part because of the set and staging: although the first duet of the opera was well-sung and dramatically acted, the mood was ruined by laughter elicited from the audience when Elena and her suitor Uberto exited the stage in a boat that was ostensibly carrying them across the lake.

Overall, City Opera’s production of La Donna had an emotional impact that was greater then the sum of its parts. While the audience seemed somewhat disinterested, we found the singers strong and Rossini’s music beautiful. A unique work in the canon, we are truly appreciative of the effort given on all fronts to put on this gem.

Sarah Gerk

Megan Jenkins

April 15, 2007

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV: Sadko

Judging by a comparison of timings, this is presumably the same performance that produced the audio recording of the work released on CD by Philips several years ago. Gergiev and the Kirov Opera have here added most significantly to their ongoing project of awakening the rest of the world to the vast treasures of Russian opera that lie beyond the better known Boris Godunov, Eugene Onegin, and Ruslan and Lyudmila, for example. In particular, their CD releases of the operas of Rimsky-Korskaov have been an exciting chapter in this project, and one can only hope that the present video release is the first step in the DVD counterpart of that chapter.

Those familiar only with Rimsky-Korsakov’s orchestral works (Scherezade, Russian Easter Festival Overture, Capriccio Espagnol) would hardly be surprised by the brilliance of the orchestral pallet in his operas – except that in the variety and imagination of his scoring he exceeds in them even the deserved credit for the path-breaking achievements of his concert works. That his operas should have called forth his best efforts in this regard is certainly reasonable, as generally they are less true operas than illustrations in sound of scenes from Russian stories and legends. One searches in vain for gripping drama, vast historical canvases, or keen psychological insights and character development, possibly one reason that Sadko, certainly one of the greatest of Rimsky’s fifteen completed operas, is so seldom seen in Western opera houses. As the composer himself admits in his memoir, My Musical Life, “The folk-life and the fantastic elements in Sadko do not, by their nature, offer purely dramatic claims” (from the Joffe translation, New York, 1972).

Of course, an essentially negative description of how Rimsky-Korsakov conceived many of his operas misses the point. His clear intent was to encapsulate the cultural flavor of Russia through adapting its stories into episodic sequences of colorful scenes enlivened by atmospheric music. The subtitle of the present work clearly reflects this intent: a bylina is an epic folk tale, and the apt term “tableaux” shows clearly that Rimsky-Korsakov was thinking visually rather than in “acts.” Furthermore, it would hardly be an exaggeration to say that musical concerns, rather than textual details, were uppermost in the composer’s mind, to the extent that an 1867 symphonic poem – Sadko, Op. 5 – provided him with both inspiration and raw musical material for the opera he completed some thirty years later (the opera was completed in 1896, first performed in public in 1897). That he remained drawn to this character and his story throughout this period is demonstrated by the several revisions he made to the original orchestral work prior to beginning the composition of the opera. Further evidence of symphonic influence lies in the motivic interconnections that bind together various scenic and character elements in the opera.

Sadko is a work dominated by the sea. The basis of the tale may be summed up by saying that the hero, Sadko, falls in love with Princess Volkhova, daughter of the Sea King, and, true to her promise, eventually finds himself in her father’s undersea kingdom where he claims her hand. On their return to his native Novgorod, she sacrifices herself to become a river, the Volkhov, which then forms a waterway to the inland city and thus ensures its economic prosperity. It is in the aural evocation of the sea that Rimsky Korsakov’s masterful use of the orchestra is at its most brilliant: The Introduction (“The Blue Sea”), the music that introduces Tableau VI in the Sea King’s palace, and the transformation music as Princess Volkhova becomes the Volkhov River in Tableau VII are but three of the most engaging examples of the composer’s magical scene painting. One is hard-pressed not to draw comparisons with his contemporaries, Ravel and Debussy, comparisons by which Rimsky-Korsakov would hardly come off as second-best. His expanded harmonic language alone, particularly in these scenes, markedly strengthens the similarities.

Conductor Valery Gergiev leads his very capable Kirov Orchestra with great sensitivity to the colors and textures of these and many other passages in Sadko, and the sound engineers have created an aural feast worthy of the players’ laudable efforts. In the passages cited above, the lighting effects, beautifully conceived throughout the work, are especially worth mentioning, as they complement the “water music” superbly. The set design and costume work likewise fulfill completely their important roles of establishing the Russian folk atmosphere while also providing a beautiful and colorful backdrop for the various scenes.

Vocally, a central and very satisfying part of this presentation is that provided by the Kirov Opera Chorus, which has plenty of opportunity to shine as a virtual protagonist in the various village scenes. They sing with power, beauty, and excellent ensemble, balancing perfectly the prominent role of the orchestra. Turning to the soloists, the three merchants, Bulat Minjelkiev, Alexander Gergalov, and Gegam Grigorian, are each outstanding in their contrasting and memorable appearances in Tableau IV; Grigorian’s interpretation of the justly famous “Song of India” is particular noteworthy. Sergei Aleksashkin uses his stentorian and characteristically Russian bass to good effect as the Sea King. Among the women, gusli-player Nezhata is well-portrayed by Larissa Diadkova, and Marianna Tarassova gives Sadko’s earth-bound and temporarily jilted wife Lyubava Buslayevna an appropriately emotional characterization. On the less satisfying side, Valentina Tsidipova, despite her beautiful if light lyric soprano, lacks the vocal depth to carry off the role of Princess Volkhova adequately. This brings us to the major disappointment here, and it is a serious one: tenor Vladimir Galusin in the title role. Admittedly, the demands on him are heavy and virtually continuous throughout the work, but Galusin rises to them only occasionally. His voice frequently sounds strained and, on more than one occasion, his intonation is annoyingly faulty.

On balance, however, even lacking a satisfactory Sadko, this production is so strong and so satisfying overall that it should immediately find its way into the collection of anyone serious about Russian opera and especially of anyone who has not yet discovered this repertoire. Visually and aurally stunning, this production will withstand repeated viewing and thus comes highly recommended.

Roy J. Guenther

The George Washington University

Handel's Flavio at NYCO

From David Zinn’s fantastic sets to the gender-bending casting to the non sequitur romp through human emotion with every new scene, the production was a delight to behold, though I fear that the novelty of combining two counter tenors and a pants role trumped all else that was wonderful.

Flavio is characteristic of full-length Handel opera, deftly combining the tragic and comic as Mozart and Rossini would later do. An on-stage death and subsequent lament is followed immediately by a comic scene involving a love triangle, which is in turn followed by a scene in which one of our heroes pleads with his love to kill him. There is always danger that such manic drama will jar the senses a bit too much, but Flavio is one of the more subtle examples in Handel’s oeuvre.

The potpourri was emphasized by Zinn’s colorful sets and costumes. Fanciful greens, pinks, yellows, and blues combined to embolden the incongruities of the work. One of the most prominent sets was a high grassy hedge, on which hung lamps belonging inside. The hedge functioned alternately as garden and throne room, leaving the audience to incorporate grass in the royal chamber and fancy lighting in the great outdoors. The costuming was equally as creative; at one point Theodata, played by Kathryn Allyn, donned the baroque version of a French maid costume.

Make no mistake, however, the night belonged to the performers, especially the high-pitched male heroes of the story. Two lead roles in this opera were written for castrati, with a third pants role to boot. While revered and sexually desired in their day, the operation involved in creating the castrato voice has since understandably fallen out of favor. So we have counter tenors instead. City Opera conveyed to the audience the import of having two men sing their falsetto out in the six-page preparatory essay in the program booklet. The article explicated the history of castrati and the modern rise of the counter tenor, which author Marion Lignana Rosenberg links to the contemporary early music revival. Rosenberg also mentions the gender issues inherent when men sing in traditionally female registers, likening the operatic trend to the popularity of high-pitched male crooners in pop music.

Indeed, although the counter tenor voice is both aesthetically beautiful and fascinating from the perspective of the historian, gender issues were key in the audience’s reception of Flavio. And how could they not be? In this city, in this business, at a critical time in the gay rights movement, it is natural and healthy that an opera with two fabulous men playing the studly heroes and a woman as the third-most-testosterone-filled character comes to the fore. And so it was that the audience’s awareness of these issues was palpable. There was dead silence, the likes of which I’ve hardly experienced, during the first counter tenor aria of the evening (ably sung by Gerald Thompson), and later giggles as Emilia, Guido’s love interest, sang “when it comes to odd lovers” (these among a slew of further examples I could note).

If members of the audience did tear their minds from such novelty, they heard a sound and capable cast. David Walker was returning to the title role, and he handled the mood changes deftly all the while singing a massive range of notes. Gerald Thompson as Guido filled the other counter tenor role. His voice was more developed although his acting left much to be desired. Katherine Rohrer played Vitige, Flavio’s servant who outwits his (or her?) master to get the girl in the end, a power play redolent of later Mozart and Rossini. Ms. Rohrer has a sweet and clear voice and first-rate comedic timing. Kathryn Allyn’s deep mezzo was well served in the role of Theodata, and Marguerite Krull sang beautifully as Emilia, especially in the lament. Indeed, Ms. Krull proved to be the most adept Handel interpreter of the bunch with her florid, effortless cadenzas. Notable too was the period orchestra, lead by William Lacey on the harpsichord. Their ensemble skills and obvious diligent work at authenticity were admirable.

In all, the New York City Opera’s production of Flavio was at once delightfully whimsical and timely. All elements pulled together to create a wonderfully incongruous whole. May we see many more such gender-bending productions in the future!

Sarah Gerk

image=http://www.operatoday.com/walker_david.png image_description=David Walker (Photo: David Rodgers) product=yes product_title=Above: David Walker (Photo: David Rodgers)ROSSINI: Mosè

Music composed by Gioachino Rossini. Libretto by Luigi Balocchi and Étienne de Jouy, Italian translation by Calisto Bassi.

First Performance: 26 March 1827, Opéra, Paris

| Principal Characters: | |

| Mosè, the Hebrews’ lawgiver | Bass |

| Elisero, his brother | Tenor |

| Faraone, King of Egypt | Bass |

| Aménofi, his son | Tenor |

| Aufide, Egyptian officer | Tenor |

| Osiride, High Priest | Bass |

| Maria, sister of Mosè | Mezzo-Soprano |

| Anaìde, her daughter | Soprano |

| Sinaide, wife of Faraone | Soprano |

| A mysterious voice | Bass |

Setting: Ancient Egypt

Synopsis:

Moses promises to lead the Israelites out of captivity in Egypt. Anaïs and her mother have been released by Pharoah on the intervention of Queen Sinaïs, who is sympathetic to the Israelites. Anaïs loves Pharoah's son, but intends to leave with her people, while her lover Amenophis has decided she must stay. Moses brings upon Egypt the plague of darkness. This is raised, with freedom again promised, while Pharoah has arranged a marriage for his son Amenophis with an Assyrian princess, to his distress. The High Priest Osiris demands that Moses pay reverence to Isis before the Israelites leave. Moses refuses and the Israelites are sent away in chains. Amenophis and Anaïs meet, he still hoping that their love may be permitted. He warns her that Pharoah's army is pursuing the Israelites, who are now triumphantly led by Moses across the Red Sea, while Pharoah's men are drowned.

Rossini adapted his earlier opera Mosè in Egitto (Moses in Egypt) as Moïse et Pharaon, ou Le passage de la Mer Rouge (Moses and Pharoah, or The Passage of the Red Sea) for Paris, with a new libretto, creating the necessary grand opera spectacle that France demanded. Staging of the French version of the work makes obviously heavier demands on resources. This second opera for Paris marks a further step by Rossini towards his fourth and final opera for the French capital, Guillaume Tell (William Tell).

Click here for the complete libretto.