The reasons are clear: Donizetti and his librettist, Cammarano, were

stage-wise pros and their work, boiled down from a verbose Walter Scott

novel, is a tight dramatic ship as well as tunefully irresistible. The sextet

has been called the most famous ensemble in opera, but it does not come from

nowhere — it bursts logically from a nervous situation, and the scene that

follows propels the excitement to a teetering high. Coloraturas prove

themselves on the Fountain Scene and the Mad Scene, but the latter, too, is

the logical result of all that has gone before. The Tomb Scene that follows

may be anticlimactic, but its beauty has lured many a great tenor to attempt

to steal the show.

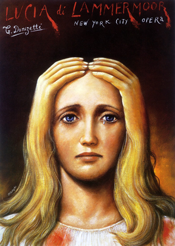

The Met has always loved Lucia; every notable Lucia of the last

124 years has sung it there. This season’s new production is the fourth to

play the New Met; its look is handsome and conservative to suit the taste of

the American opera audience. The era has been warped to the late nineteenth

century for no obvious reason, though it does permit Natalie Dessay to wear a

tight Empress Sisi riding habit in Act I and glamorous red silk in Act II. (I

thought the Ashtons were strapped for money?) In the Met’s previous

Lucia, properly set two hundred years earlier, zaftig Ruth Ann

Swenson was unattractively got up as one of Charles II’s bare-breasted

floozies, but Dessay is the raison d’être of the show — her

maddened face is all over New York, on every news and subway kiosk — and

she presumably had more influence with the costume shop. (“She’d look

good in anything,” muttered the woman beside me.)

The director is Mary Zimmerman, who like so many tyros brought in by the

Gelb regime, has never staged an opera before. Her theater skills are

evident, but also her unfamiliarity with the form. In bel canto opera,

singing is the primary focus — everything else seems secondary because it

is secondary. Beautiful music is where the drama occurs, and such acting as

may occur should support that. It’s very exciting when singers can act, as

nowadays most of them can, and Dessay is famous for it — but it’s not

primary. That is the message someone should have explained to Zimmerman when

she grew impatient — as, alas, she did — with moments, minutes, of mere

music.

It will puzzle anyone who knows Lucia why any director would

upstage the famous sextet, but that is what Zimmerman has done by introducing

a new character — a fussy society photographer — who is busily placing

people for a Victorian wedding photo, so that instead of a tragic crisis, we

have a giggly skit. Very funny, but why is it here? Does Zimmerman think this

is a comic opera? Three new corpses for Six Feet Under, perhaps?

Zimmerman obliges us to choose between paying attention to her or paying

attention to the opera, which is just what I object to about new wave opera

directors. She distracts us from Dessay’s lovely account of “Regnava nel

silenzio” by bringing on the ghost of whom the aria tells. The ghost

tiptoes down a hill, beckons, and vanishes into the well, very intriguing,

but who, then, is paying attention to Dessay’s singing? Only those who know

it, and force themselves to ignore the stage. Again, when Raimondo,

beautifully sung by John Relyea, admonishes Lucia to accept her fate in an

aria often cut, many people may not notice because a bunch of servants behind

him are changing the Act II set from scene 1 to scene 2. With a camera,

Zimmerman could focus our attention on Relyea; on a stage the size of the

Met’s, his artistry goes almost for naught. Too, if Lucia and Arturo are

seen mounting the staircase at the beginning of what will become the Mad

Scene, they have less than two minutes for Lucia to go mad, find a knife,

stab him 23 times, drench herself in blood, and be discovered before Raimondo

rushes back to the hall with the news. Then there’s the doctor who comes on

in mid Mad Scene to administer the injection that (we must infer) causes

Dessay’s death and the exquisite and fanciful variations of her

cabaletta — it’s amusing, but this is supposed to be a tragic melodrama,

not sketch comedy. At last, in the Tomb Scene finale, when Marcello Giordani

is pouring his heart out in the tenor’s big solo moment, Dessay returns,

costumed in the ghost’s gray-white from Act I, and distracts us from his

singing. Thinking of ways to take our minds off the singing appears to be

Zimmerman’s first principle of opera direction. The singing, at least with

this cast, is too good for this.

At the October 5 performance, two weeks after the premiere, the star was

certainly Dessay, and it was a performance of the role not of the music

alone, the vocalism never divorced from the neurotic girl giving way under

emotional pressure. Her faints and mad, inappropriate giggles were credible,

as was the shock of the guests (and ourselves, familiar with the piece as we

might be) at the sight of this birdlike creature’s indecorous behavior.

Dessay’s is a Lucia for the present day, when coloratura shenanigans are

expected to defer to character. The contrast of her freakish acting with the

formality of Donizetti’s melodies and ornaments created an uneasy

disjuncture; this is simply not a naturalistic part. But edge can be good in

the theater; in time it can become custom: There were charges of

tastelessness when Sutherland, fifty years ago, became the first Lucia to

have blood on her dress at all. (“She stabbed him over and over!” she

pointed out at the time.) Psychologist Brigid Brophy noted that to see a

virgin bride stained with blood was not unusual — to see her in her

husband’s blood gave the story a jolt. Lucia has always submitted

to one strong-willed man or another. Going murderously mad is her way of

fighting back. None of the men expect this, and with so petite and (in Act

II) pallid a Lucia, it is especially unsettling.

Dessay makes the opera her own by forceful acting, and sings her arias

beautifully, but her tiny voice does not command it — she can be

overpowered whenever any other voice sings, obliging her to hold her high

notes until she can be sure she’s got a clear place to insert them.

(Someone should advise the Alisa, Michaela Martens, that it is not good form

to drown out the diva at an act finale.) Her ornaments are prettily executed,

often given dramatic point by gesture or attitude, but their function of

illustrating the character’s state of mind has been usurped by those

gestures or, worse, by ghosts, doctors and other distractions. She may be

more thrilling to see than to hear.

As Edgardo, Marcello Giordani sang with a liquid tenor thriving on the

duet with Dessay and, best of all, his morbid double-aria in the final scene.

More passionate outbursts — the famous “Maledizione” of Act II —

seemed to push him towards shrillness rather than intensity, and his “Come

on, fight me” gestures to the furious wedding guests were awfully Italian

in so rigidly Scottish a production. As Enrico, Mariusz Kwiecien’s best act

was the second, the suave, menacing duet that breaks his sister’s will —

he was close to cracking during what should be the cold fury of the opening

scene and withdrew due to illness before Act III’s Wolf’s Crag scene,

replaced by a capable debutante Stephen Gaertner. John Relyea, as Raimondo,

turned in the best-judged performance for the style of the music and the even

flow of line. Young Stephen Costello, the hapless Arturo, has an exciting

sound that has aroused comment, but his high notes were not without strain.

It was James Levine’s night off; Jens Georg Bachmann, his replacement, kept

the singers cued and the drama tight.

John Yohalem