(Not only for Mozart – his libretti for Martin y Soler and

Salieri are generically similar, their characters similarly self-aware.)

Take, for example – and I will explain my reasons for bringing her

up in particular – Donna Anna. As Brigid Brophy notes, in Mozart

the Dramatist, we will never know what passed between her and Don

Giovanni in the moments before the curtain rises – people have been

debating it for two hundred years, and each age, cynical or idealistic by

turns, guesses what it wants to guess from the evidence. We first meet an

Anna outraged at Giovanni’s attack – which is still in progress

– and only her own furious resistance prevents his easy success, and

then commences her unappeasable rage at her father’s murder. In

contrast, there is her tenderness for Don Ottavio in the prayer trio, and in

“Non mi dir” – such slight moments we might overlook them,

as those who don’t like Ottavio much tend to do – too, we

are a bit tired by the time “Non mi dir,” the

opera’s last aria, rolls around. Yet surely these are the normal Donna

Anna, the Anna who existed before abnormal events, assault and murder,

released a new, furious figure on Seville, and her life and relationships

– not least, her relationship with herself. That she asks Ottavio for

another year to ponder the events of the last 24 hours before she weds him

always raises a snicker nowadays (it certainly does at the Met), but that she

wants some time to breathe, to think, to understand the outrages that have

transformed the orderly world she was raised to believe in seems entirely

within character. Will she hold out for a full year of formal mourning? Will

she break down and elope – with Ottavio or someone more dashing? Will

she ever bring herself to yield to the too-courteous Ottavio? Mozart and da

Ponte preferred to leave us uncertain – they liked us like

that.

Some analysts – especially stage directors – do not agree:

Frank Corsaro insisted Anna was after the “Big O”; having had her

first sexual encounter and craving more – which seems to me most

unlikely for this formal, uptight woman in response to rape. It is nowadays a

cliché (perpetuated in Marthe Keller’s vulgar and ugly Met staging) to

have Anna yielding to Giovanni at the end of the opening trio, falling into

his arms right there on the ground, but no note of the music or word of the

libretto justifies such an interpretation, and the scene was never presented

this way until quite recent times. This view of Anna’s motivation is

not itself modern – in a celebrated tale of E.T.A. Hoffman. a bare

generation after Mozart’s time, the real Donna Anna appeared in

Hoffman’s box during a performance of the opera and explained that her

anger was all an act, concealing true love. This is not the way modern

directors see her either – they tend to regard Donna Elvira as the

devotee, Anna as a neurotic, a creature of artifice, of propriety, incapable

of – or at least out of touch with – genuine feelings. And G.B.

Shaw (a man without sexuality himself, whose creations seldom have much of

it) made his Ann the self-conscious mother of the future Superman, seeking

the proper father for such a being – which still does not explain why

she would choose Shaw’s sexless and misogynistic Jack Tanner for the

part.

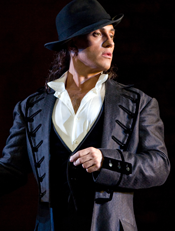

Erwin Schrott in the title role and Isabel Leonard as Zerlina in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.”

Erwin Schrott in the title role and Isabel Leonard as Zerlina in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.”

Anna’s emotions must be examined because the music supports any and

all of these interpretations: Donna Anna must be in control of a

voice’s ornamental capacities both when howling for revenge and when

expressing dulcet sentiments to her faithful fiancé. She must be capable of

seizing our attention with the rages of her initial trio and duet, of holding

us through the long accompanied recitative of her narrative of assault and

resistance, of performing “Non mi dir” at the shank’s end

of a long night, and of still singing beautifully in the final sextet. (Some

directors finesse that by omitting the finale entirely. If the Anna is not a

brilliant singer, they will even cut “Non mi dir.”)

So it is that though I have heard perfect Don Giovannis, perfect

Leporellos, perfect Ottavios and Zerlinas and even (not often) Elviras, I

have never encountered, on stage or on recording, a perfect Donna

Anna – one who made the role complete, explicable, musical, at once

beautiful and irresistibly exciting. As with Norma or Tosca or Isolde, I do

not expect ever to hear one singer draw all the threads, the possibilities,

the range of this character into a single portrayal, and make it a thing of

beauty besides.

Susan Graham as Donna Elvira in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.”

Susan Graham as Donna Elvira in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.”

I bring all this up because the Met’s most recent Donna Anna,

Krassimira Stoyanova, comes about as close as I ever expect to hear. My date

said, “95 percent,” which I’ll accept; an older friend

said, “No one as good since Eleanor Steber,” whom I never heard,

but whose Mozart technique as recorded was nonpareil. My best Anna to date

was that of Carol Vaness in the early ’80s at the City Opera,

beautiful, fiery, classy, but lacking the tenderness, the occasional

vulnerability Stoyanova gives us at those moments when Anna is alone with her

own soul and need not put on an act.

Stoyanova, who is the toast of Vienna and Barcelona (her superb Desdemona,

Luisa Miler and Violetta can be heard on webcast from those houses),

possesses one of the most beautiful soprano voices before the public today.

In the prayer and in “Non mi dir,” it was impossible not to focus

on each note – one did not want to miss any one of them; one did not

want the moment to end. And yet it was not the beauty of the voice but its

range of color, the forceful statement of each phrase that riveted us during

the narration of Giovanni’s attempted rape that leads up to “Or

sai che l’onore.” She was all steel here, without sacrificing

beauty of tone: every word, every phrase meant something. Without

eliminating the possibility that Anna is covering something up while speaking

to her lover, she gave us a woman outraged, stirred and alarming, even to

herself. Her ornaments were tasteful and, as her Anna Bolena for Queler

demonstrated, capable of expressing rage and inner torment – but there

were turns in “Non mi dir” (where so many Annas come to grief)

that were less than ideal – her only such moments, and it was still a

“Non mi dir” that deserved – and got – the loudest

ovation of the night. The duet with Polenzani’s Ottavio during the

finale could have gone on all weekend for my money: I would never say hold,

enough! This is a singing actress of the rarest quality, as a vocalist and a

performer, and it is a tragedy for us in New York that the Met doesn’t

appreciate her.

Krassimira Stoyanova as Donna Anna in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.”

Krassimira Stoyanova as Donna Anna in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.”

I had never heard Erwin Schrott before, and concur that he has the

swagger, the elegance, the wit, and the solid top-to-bottom lyric bass for

the role. He tends to play the charming Don rather than the brutal Don

– an ideal Don must be both. Somehow, Schrott has such fun acting the

role that he does not put his energy into singing its vocal high points. His

arias passed almost without notice – there was no sweetness in the

serenade, little exuberance in the Champagne Aria. I cannot remember if it is

Keller’s idea to have Giovanni without a mask in both the opening scene

(which obliges Anna to contort herself so as not to see him) and in the scene

with Masetto’s friends, when a mere hat would do. Was Schrott afraid to

conceal his pretty face? Or did the director fear audiences would be confused

by his disguise as Leporello? What confused me was how Anna could not

recognize him, and how a high collar could disguise him from Masetto.

Considering Scrott’s formidable height and muscularity, and that of

his voice, this was a surprisingly insubstantial Giovanni.

Ildebrando D’Arcangelo as Leporello in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.”

Ildebrando D’Arcangelo as Leporello in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.”

Ildebrando D’Arcangelo (and, in the next performance, Ildar

Abdrazakov) seemed to be having the most fun of the evening. Keller seems to

like Leporello so much and to dislike Giovanni so much that she has given the

valet all the good moments. Scrott and D’Arcangelo played like

vaudeville partners, mugging and traipsing and interacting, and their delight

was infectious, but though this is certainly the most intimate relationship

of Giovanni’s life (in the libretto we often see one of the pair

imitating the other, or protecting, or cautioning), as played here it did not

allow much room for the ladies or the plot. They would play a good skit

on Don Giovanni; I’m not sure this allows us a view into the

opera as a serious drama.

Matthew Polenzani is one of the finest Mozart tenors now before the

public, and he has emerged as a favorite with Met audiences as well; his

“Dalla sua pace” was strong, but his breath control was not quite

up to “Il mio Tesoro.” For me, his finest singing all night was

the five minutes of duet with Stoyanova in the finale, when his, warm,

supportive sound acted like a ballet cavalier to his lady.

Susan Graham’s mezzo had no problem with the (slightly lowered)

music of Donna Elvira, and she wielded her height to make the scenes with

Leporello comic, but the instrument itself lacks the soprano sheen one

recalls of the greatest Elviras. It’s a pity that the Met has so many

mezzos on hand they have seem to have lowered this role as a regular

habit.

I don’t often approve of mezzos Zerlinas either, although that can

pass as long as this flirtatious but demure peasant bride is not a slut

sticking her rear end in the air in the middle of the public street, as

Keller (and too many other recent directors) demand. Isabel Leonard was in

some trouble on the tenth, and was replaced in Act II by Monica Yunus, who

also replaced her in the performance on the fourteenth – a short,

pretty woman with a bright, easy soprano of no obvious individuality. She

seemed able enough on stage. Both Zerlina and Masetto are obliged to do

rather complicated steps, mimicked by dancers, in their entrance duet –

an assignment Leonard and Yunus and their Masetto, Joshua Bloom, handled with

style. Bloom has a winning presence and a voice of great character and, well,

bloom – I look forward to his Figaro and Papageno. Here, after slamming

Marthe Keller, I must insert a word of praise: the scene in the Act I finale

where Leporello and Giovanni manage to separate Zerlina and Masetto, usually

so inexplicable, is very cleverly handled here, as Leporello sics a peasant

girl on Masetto, and she refuses to leave him alone.

Louis Langré, the head of the Mostly Mozart orchestra, demonstrated who

his favorite composer is, drawing out the light, luscious touches that make

every Don Giovanni as much a revelation as one’s first. He

will return with the production this spring, with Peter Mattei’s highly

praised Giovanni.

John Yohalem