At a ceremony marking the launch of the 63rd Festival, Ireland’s

Minister for Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Heather Humphrey, announced the

renaming of the award-winning Wexford Opera House as Ireland’s National Opera

House — no longer will Ireland by the only country in the EU not to possess a

‘National Opera House’.

In the words of WFO Chief Executive David McLoughlin, ‘This landmark

development of official recognition of Ireland’s National Opera House will

help secure a legacy in opera in Ireland for generations to come, but perhaps

more importantly deservedly recognises the State’s previous significant

investment [the Department of Arts has invested more than €31 million in the

Wexford Opera House] in the creation of what has been internationally acclaimed

as ‘the best small opera house in the world’.’ No doubt the finer details

of the ‘partnership’ still need to be bashed out, but this state

endorsement can only be good news for WFO, adding to the optimism generated by

the news of a 10% increase in ticket sales this year, with almost 90% cent of

the 21,500 tickets the three main-stage operas, Short Works, lunchtime recitals

and other performances reported sold at the start of the Festival. WFO is now

well-placed to continue its cultural mission to raise awareness of Irish opera

production at home and abroad; to support the careers of burgeoning singers,

designers and directors; and, of course, to evangelise for operas which have

been lost, unloved and over-looked.

Marie-Ève Munger as Rosa and Filippo Fontana as Don Bucefalo

Marie-Ève Munger as Rosa and Filippo Fontana as Don Bucefalo

Antonio Cagnoni’s comic caper, Don Bucefalo (seen on Thursday

23rd October), is one such neglected rarity. Composed as a

graduation piece, it premiered on 28th June 1847 at the Milan

Conservatory and demonstrates the teenage Cagnoni’s slick facility with

contemporary Italian operatic idioms, as the nineteen-year-old student pays

skilful homage to his masterful ottocento forebears. With echoes of

Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore (the eponymous con-man is peddling

musical elixirs rather than love potions) and Rossini’sIl barbiere di

Siviglia (the singing lesson scenes remind one of Rosina’s show-stopping

number), it’s easy to see why Don Bucefalo was an instant success in

1847; snapped up by music publisher Giovanni Ricordi, the work triumphed across

Italy. Yet, while Cagnoni (1828-96) composed more than a dozen more operas

after this his third essay in the genre, posterity has remarked little more

than his contribution to the composite mass written in memory of Rossini in

1869.

The score is ear-pleasing, if ultimately the melodies prove unmemorable. The

‘plot’ is similarly insubstantial (the libretto by Calisto Bassi was based

on Giuseppe Palmoba’s Le cantatrice villane). Don Bucefalo, a

pompous chorus master, arrives in town and wants to put on a performance of his

new opera. He promises the locals — budding singers, thespians and

artistes — that their voices are magnificent but untrained, and that

his coaching will turn them into stars, initiating fierce competitive rivalry

between Rosa and Agata who both think they deserve to be the prima

donna. Singing lessons and rehearsals ensue, and the theatrical

resentments are equalled by amorous jealousies as Rosa is pursued by three

ardent admirers, one of whom turns out to be her 'dead’ husband (disguised

and home from the wars). There’s much silly business, and ‘busyness’, but

it all works out alright in the end. As ’theatre about theatre’, Don

Bucefalo may not challenge Michael Frayn’s Noises Off or

Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos, but in the hands of director

Kevin Newbury and his set designer Victoria (Vita) Tzykun it makes for a jaunty

evening — a highly professional celebration of the absurdly ‘amateur’.

Newbury sets the opera in a 1980-ish multi-purpose recreation centre,

equipped with a small stage, a café, and various sporting and theatrical

apparatus, including a climbing frame, basketball hoop and stacks of gaudy

plastic chairs. Primary colours clash loudly but cheerfully (in a programme

article, Newbury explains that he was recalling the community centres in Maine

where he himself rehearsed countless am dram productions during his youth). A

raised office on the left of the stage allows for the clichés of romancing and

snooping to be indulged. And, the stage is cluttered with home-made props and

scenery: the cut-out flowers, sparkly suns and moons, and over-sized clouds —

as well as an outmoded Casio keyboard and a decidedly ‘square’ cotton-wool

sheep — wittily accessorise the musical numbers.

Cagnoni’s score places considerable emphasis on the ensembles and Newbury

is inventive in marshalling the large chorus, whether they are participating in

a gentle aerobics warm-up or show-casing their ‘talents’ — as conjurors,

dancers, acrobats, ventriloquists, sock-puppeteers and the like — in a bid

for glory in Don Bucefalo’s new show.

The principals all acquitted themselves well. As Rosa, the Québecian

soprano Marie-Ève Munger sparkled with diva-like presence; her full, rich

soprano gained in suppleness and sumptuousness the higher it climbed, and at

the very top it gleamed with a silvery shine, yet in her Act I

(Bellini-indebted) cavatina, she showed that she can shape an affecting line

too. Accompanied by pianist Sonia Ben-Santamaria, Munger similarly balanced

lyricism and coloratura brilliance in a French repertoire-dominated lunchtime

recital, in which the caressing, long-breathed melodies of Canteloube’s

Songs of the Auvergne were complemented by the lucidity of

Debussy and the suavity of 1940s’ Gallicism. Here she was a winning prima

donna, by turns sensuous and crystalline according to dramatic context —

it’s no surprise that Rosa has at least three enamoured devotees hot on her

heels.

As Don Marco — the petulant, envious neighbour who resents the success of

Don Bucefalo’s musical seduction of Rosa — Italian tenor Davide Bartolucci

swept through the nonsense patter of the Act 1 finale with aplomb (full marks

for Jonathan Burton’s hilarious translation), fiery fury and crisp

articulation proving preposterous but hysterical bedfellows. Tenor Matthew

Newlin revealed a sweet lyricism, a self-knowing sense of humour, and many a

well-shaped diminuendo as the Count di Belprato, while Peter Davorin brought a

ring of authoritative clarity to the role of Carlino (Rosa’s husband, posing

as his own brother). Irish soprano Jennifer Davis was dramatically convincing

as Agata, and successfully conveyed genuine emotional depths in her Act 3

cavatina.

But, the success of the production was primarily indebted to the consummate

musical and dramatic skill of Italian bass Filippo Fontano in the title role.

Last year, I noted that as Beaupertuis, in Nino Rota’s Il Capello Di

Paglia Di Firenza, Fontana ‘stayed the right side of parody and his

focused bass baritone brought some depth to the role’; this year he was

superlative in balancing Don Bucefalo’s bombast and genuine self-belief. The

music-master’s ‘real-time’ rehearsal of the Wexford Festival Opera

orchestra and the scatter-brained performance which followed were an absolute

scream; he called for naïve effects and colours — a dash of

fortissimo here, a squeal from the piccolo there — gradually

building his score (which literally unravelled like a concertina paper trail

across the forestage), adding instruments and timbres one by one, until he

achieved the climax: three bars of rising triplets from the whole orchestra

that sound amazingly like heart-tugging Verdi. No wonder Cagnoni’s

opera-going contemporaries lapped it up.

Spanish conductor Sergio Alapont was impressively collected and commanding

in the pit. Conducting the Wexford Festival Opera with brio and clarity,

Alapont managed the breakneck tempi with unruffled éclat,

and made the busy score dance nimbly. ‘Totally bonkers yet immensely

entertaining’ best sums up both the opera and Newbury’s production.

If Don Bucefalo suggests that a good song can bring a community

together, then the Pulitzer prize-winning Silent Night by composer

Kevin Puts and librettist Mark Campbell dramatically depicts the power of music

to bring about peace between warring factions (24th October). First

seen in November 2011 in Minnesota, Silent Night is based upon

Christian Caron’s screenplay for director Christophe Rossignon’s 2005 film,

Joyeux Noël, about the WW1 Christmas truce of December 1914.

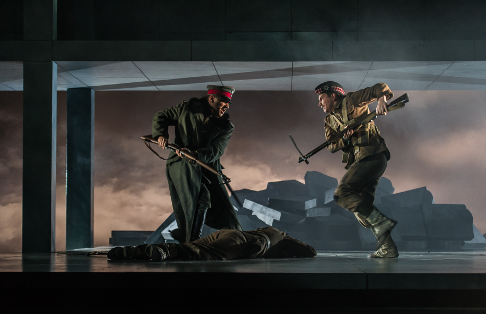

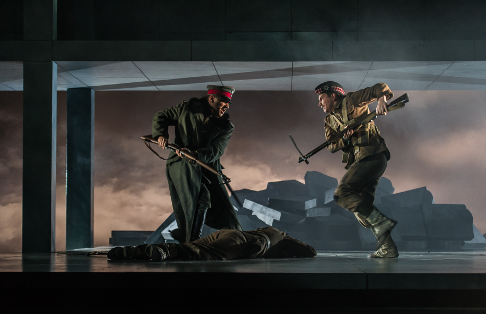

Philip Horst and Ryan Ross

Philip Horst and Ryan Ross

Rossignon presents the horror of war as experienced through the private

stories of individual soldiers who face each other in the trenches. When

Jonathan Dale’s older brother William is killed, Jonathan is overcome by

guilt at leaving his brother’s body unburied on no-man’s-land, and the

young Scottish recruit vows vengeance. In a village in occupied France, only a

short distance from the front line, Madeleine Audebert gives birth to a child

while her husband, Lieutenant Audebert, struggles to bravely lead his men and

put aside his anguished longing for his absent wife and unknown child. In

Germany, an opera performance by esteemed tenor Nikolaus Sprink and his lover,

the Danish soprano Anna Sørensen, is interrupted by a German officer

announcing the commencement of hostilities and the calling up of reservists.

After five months of war, a truce comes about on Christmas Eve, when the

Scottish regiment’s bag-piping and carols are heard by the French and German

soldiers, lying in their trenches just yards away. Sprink has just returned

from a performance at the Crown Prince’s residence (a recital which had been

arranged, somewhat improbably, by Anna to enable the lovers to spend one more

night together); now, he is urged by Anna (who, even more improbably has

accompanied him back to the front line) to sing for his comrades. A Scottish

piper joins in as Sprink’s powerful rendition of ‘Stille Nacht’ rings

across the corpse-strewn no-man’s-land. The commanding officers agree a

cessation of fighting: food and drink are exchanged, a football game ensues —

only Jonathan remains aloof, unmoved, stymied by grief. Later, reprimanded by

their superior officers for cowardice and fraternising with the enemy, the

regiments are transferred to other points on the front line; as the Germans

depart for Eastern Prussia, they hum a carol they have learned from the Scots.

Campbell sticks closely to the original screenplay. The text is simplified

as necessary (it takes longer to sing words than to speak them) but essentially

the characters and events are retained, although there are some small changes

of emphasis: for example, the relationship between Nikolaus and Anna is

(appositely) less sentimental than in the film (although Anna’s appearance in

the trenches is no more credible…). Herein lies the problem, though: for, in

following the action and actual text of the film so faithfully, Puts and

Campbell have not so much created something ‘new’ — a musico-dramatic

form and medium which can ‘tell its story’ through the score — but rather

have produced a musical accompaniment to the original film. Certainly, Puts’

can find the notes and colours to capture the tenor of any given moment, and

wonderful solos from the cello, horn and harp powerfully sway our emotions. One

of the most affecting moments comes in the ‘aria’ in which Audebert reviews

the number of French casualties while daydreaming about his wife back home,

leading him to question the validity of the entire war: a repeating three-note

harp motif is supported by gently shifting harmonies, evoking a reflective

tenderness which contrasts starkly with the carnage outside Audebert’s

bunker. One longs for more of this sort of ‘operatic’ moment, and a greater

restructuring of the screenplay to allow the musico-dramatic forms to

communicate ‘meaning’. But, more frequently Puts’ score does not take us

‘inside’ the characters and situations in this way.

Sinead Mulhern and cast of Silent Night

Sinead Mulhern and cast of Silent Night

Presenting the annual Dr Tom Walsh lecture, on the morning of

25th October, in response to a question from an audience member Puts

and Campbell explained why they had titled their opera Silent Night

but had not included the actual carol in the score: they made the decision that

all the music should be original (thus Schubert’s ‘Ave Maria’ and

Bach’s ‘Bist du bei mir’ as performed by Anna and Nikolaus — and sung

in the film by Natalie Dessay and Rolando Villazón — are also replaced by

original music). Feeling that the pun works best if we do not hear ‘Stille

Nacht’ itself, Puts emphasised that the ‘silence was the point’. Fair

enough; but I can’t help feeling that a shift of musical register, from

Puts’ personal idiom to a set-piece song, would have produced the same sort

of magical transformation that Sprink’s carol singing effects in the film,

highlighting the power of song to salve and unite. In fact, Puts does achieve

this sense of unity in the notable ensemble for the five principals which ends

the Prologue, where three languages blend in a chorus of war songs.

Campbell’s libretto is fittingly sparse and economical, but at times the

libretto seems almost too spare: the most powerful lines are often drawn

directly from the screenplay but, pared down, they can lack inference and

depth, even seeming banal. Rossignon’s moments of black humour — ‘grim

gaiety’ is perhaps an apt term — can occasionally seem trivial in the

opera, where relationships are only sketched and some of the bitter irony of

the film is lost. Thus, in the film Horstmayer, the Jewish German Lieutenant,

remarks that it is no wonder that his French is better than Audebert’s

German, for the latter does not have a German wife, a telling detail which the

audience thoughtfully absorb, appreciating the numerous ironic implications. In

Campbell’s the libretto, the inferences in Horstmayer’s statement are

transformed into a straightforward piece of information that the German officer

is married to a French woman. Perhaps such directness is necessary in opera,

but something of the moving resonance of the film is lost. Similarly, it would

be easy in the darkness of the final scene, to overlook the fact that it is

Jonathan Dane who, in his angry misery, kills Ponchel, the wry French

aide-de-camp who has been such a strong support to Audebert: in the

cinema, the moment when Audebert hears Ponchel’s trusty alarm clock ringing

and rushes from the trench to learn that the dying Frenchman, aided by a German

soldier who has lent him a uniform, has visited his mother, to share a familiar

morning coffee, and has learned that Audebert has a son named Henri, is

distressingly poignant.

I have to allow, though, that my misgivings did not seem to be shared by the

Wexford audience, who gave the performance on 24th October a

standing ovation. There were screenings of Joyeux Noël in the Jerome

Hynes Theatre on days of Silent Night performances, and I suspect that

my reaction to the opera was influenced by the fact that I had seen

Rossignon’s film just hours before! There is no denying that there are many

touching moments in Puts’ score, or that the opera communicates a rich range

of emotions: thus, the affecting farewell scene for Audebert and his wife is

brutally swept aside by a vivid and disturbing depiction of physical combat.

Puts melds different musical idioms with skill and can move slickly from the

harmonious recreation of a Mozartian opera scene to the jolting shudders and

violent cacophony of battle. There are imitation folk songs with bagpipe

accompaniment (played by James Stone), a pastiche Latin Mass, even a fugue as

the German soldiers decorate their bunker with the Tannenbäume sent

by the Kronprinz.

Moreover, the Wexford cast serve Puts well, injecting character and passion

into their arioso lines. As Nikolaus Sprink, tenor Chad Johnson

reprised the role he performed at Fort Worth in May; impressive of stature,

Johnson’s ardent tone and sure upper register did much to establish Sprink as

a three-dimensional character, fraught with inner conflicts and anxiety.

Horstmayer’s dilemmas in many ways embody the opera’s central moral

conflicts, and Johnson’s American compatriot Philip Horst used his dark

bass-baritone well to convey the complexities which disturb the Jewish German

officer’s sense of duty.

Matthew Worth brought a nostalgic warmth to Audebert’s reflections; his

sensitive phrasing and well-centred baritone suggested the honour and honesty

of the French Lieutenant, and Worth and Dutch baritone Quirijn de Lang as

Ponchel established a strong relationship, the latter adding just the right

touch of irrepressibility and charm to his portrayal of the ‘best barber in

Lens’.

Irish baritone Gavan Ring was strong as the Scottish officer, Lieutenant

Gordon, while Jonathan Dale’s distress and bitter despair was powerfully

conveyed by tenor Alexander Sprague, the light sweetness of his tone suggesting

the brave Scot’s youthful vulnerability. The almost entirely male world of

the opera was alleviated by Sinéad Mulhern’s bracing presentation of the

strong-willed Anna, which was complemented by Kate Allen’s sympathetic

Madeleine Audebert, the latter’s sumptuous mezzo inspiring empathy and

understanding.

Director Tomer Zvulun and set designer Erhard Rom divide the Wexford stage

vertically, so that we see the three regiments stacked above one another; this

is an ingenious design which allows us to witness simultaneous actions and

experiences. In particular, the gradual drawing down of a grey curtain as the

‘disgraced’ regiments are sent to different points on the front line was

powerfully evocative of the deaths which surely await them. In the pit,

conductor Michael Christie did much to highlight the lyricism of the score.

Silent Night is Kevin Puts’ first opera. A review of the July

2014 Cincinnati production in Classical Voice North America reported

that Puts had remarked during a panel discussion that he had watched parts of

Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan for inspiration. The young

composer is currently working with Campbell on a second opera, based on Richard

Condon’s political thriller, The Manchurian Candidate, which will be

premiered in March 2015 at Minnesota Opera, and one hopes that as he becomes

more familiar with the genre, Puts will rely less obviously on cinematic forms

and exploit more directly and fully the potential of operatic structures and

means; this will also surely allow him to further develop his own distinctive

voice.

Most opera-lovers will know that Oscar Wilde’s French play

Salomé inspired Richard Strauss’s 1905 opera (the libretto was

based on Hedwig Lachmann's German translation of Wilde, which was itself

inspired by Flaubert’s Hérodias), but more recently I was intrigued

to find that the seventeenth-century Italian, Alessandro Stradella, had offered

a Baroque take on the infamous Herod/John the Baptist/Salome triangle in his

1675 ‘oratorio’ San Giovanni Battista [see my review of the

performance at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in June]. Now Wexford

Festival Opera has drawn our attention to yet another Salomé: Antoine

Mariotte’s one-act opera, also to a libretto based on Wilde. Indeed, Mariotte

began composing his opera before Strauss, but it was not premiered until 1908,

in Grand-Théâtre de Lyon, three years after Strauss’s Dresden performance.

Rosetta Cucchi’s production is fairly straightforward; the stage is awash

with amber and ochre textiles and light, and set designer Tiziano Santi has

crafted a series of proscenium arches which recede into the veiled hinterland.

Hérodias’ Page (sung with poise and a fluid legato line by mezzo-soprano

Emma Watkinson) is omnipresent. Given that almost all of the audience will be

familiar with the tale, there is no real dramatic tension in Mariotte’s work:

the libretto is structured as a series of tableaux, with an intense focus on

the eponymous debauchee, and Wexford’s decision to interrupt this sequence of

short scenes with a 30-minute interval is questionable.

In the title role, the Israeli mezzo-soprano Na’ama Goldman revealed a

lustrous, appealing tone, but occasionally she lacked the power and stamina to

project through and above Mariotte’s rather dense orchestration, with its

often low-lying, polyphonic complexities. The infamous ‘Dance’ was less

than seductive, but this was not entirely Goldman’s fault, as Mariotte’s

music seems, oddly, at its least exotic at this point; in addition, Vittorio

Colella’s choreography relied too much (here and throughout the opera) on

disengaging writhing and squirming. We were at least spared a gory head, a

silver crown substituting for the Baptist’s bloody skull.

Strangely, Mariotte’s opera does not feature a soprano role; both

Hérodias and Salomé are cast as mezzos. Nora Sourouzian (who made such a

strong impression in last year’s Massenet double bill —)

made much of Hérodias’ brief but characterful appearances. Similarly, the

lunchtime recital that the French-Canadian mezzo-soprano offered with pianist

Carmen Santoro show-cased Sourouzian’s affinity with tragic, lyrical

repertoire: particularly impressive was Berlioz’s La Mort de

Cléopatre (the first time that Sourouzian had performed the work in

public) in which the mezzo soprano demonstrated her dramatic nous

(especially her ability to ground Berlioz’s more histrionic tendencies) and

velvety tone to splendid effect. As Mariotte’s queen, Sourouzian was a

vibrant, emotionally intense Hérodias, and her vocal splendour was pleasingly

complemented by Scott Wilde’s authoritative, attractive Hérode; but, it was

the shining baritone of Igor Golovatenko’s Iokanaan which was the stand-out

performance of the evening. Golovatenko’s striking on-stage presence was

matched by the beauty of his dark timbre, confirming the strong impression he

made last year at Wexford, as Gustavo in the award-winning production of

Foroni’s Cristina, regina di Svezia.

David Angus inspired strong orchestral playing and the Wexford Festival

Orchestra captured the poetic, symboliste intensity of Mariotte’s

score with considerable accomplishment. But, while one lauds Wexford’s

continuing support for the underdog, this is a Salomé which need not

dance again.

In addition to the three main-stage production, WFO offered its usual

complement of concerts, recitals and Short Works. The latter were housed in

White’s Hotel this year, and while there were clearly economic restraints

operating, the varied repertory performed was no less rewarding. Best of the

bunch was director Robert Recchia’s witty version of Rossini’s La

Cenerentola (25th October) — a master-class in how to mount

an opera with just a tatty chair and cinema reel to set the scene. Recchia

demonstrated his creative ingenuity last year, with a L’elisir

d’amore that I described as ‘ingenious, transferring the action to a

modern-day Irish Karaoke bar — one of the virtues of which was to provide a

naturalistic raison d’être for surtitles!’ Recchia made use of

visual media again, but if he might be accused of pursuing a single idea, he

certainly justified his approach, setting Rossini’s ‘fairy-tale’ in the

very prosaic world of 1930s cinema and utterly convincing with his

‘concept’. Don Magnifico — an ebullient Davide Bartolucci — is the

proprietor of Magnifico’s motion picture emporium, his daughters Clorinda and

Tisbe are rather over-dressed usherettes, while Angelina — Rossini’s

‘Cinders’ — sweeps the aisles. Stepping through the video-projections,

the characters persuasively move between reality and artifice.

In the title role, Kate Allen revealed a strikingly rich mezzo register, the

ability to climb to the stratosphere, and astonishing flexibility and accuracy

in the virtuosic coloratura: a diva in the making. Rebecca Goulden (Clorinda)

and Kristin Finnigan (Tisbe) gave engaging performances, while Eamonn Mulhall

was an appealing Prince Ramiro, his tenor soft and caressing, and his upper

register secure and unforced. Filippo Fontana made another welcome appearance

as Dandini, and the male quartet which formed the chorus (tenors Peter

O’Donohue and Jon Valender, and baritones Ciarán Wootten and Matthew

Kellett) were efficiently marshalled by Recchio. At the keyboard, music

director Gregory Ritchey negotiated the fistfuls of notes — although

occasionally his impetuous singers left him straggling — and as Rossini

morphed effortlessly into 1940s be-bop, one might be forgiven for thinking that

one had imbibed too much of Ramiro’s champagne!

Puccini’s Il Tabarro provided a tragic contrast on

24th October. If Dafydd Williams’ concept — ‘White’s Hotel

enables us to bring this piece to life in exciting and engaging ways. As part

of the production you will find yourselves sitting in the hold of the barge as

the narrative unfolds on the barge in front of and around you’ — proved

rather more fanciful than Rossini’s romance, there was certainly much

powerful and moving singing on display. Quentin Hayes was a complex and

intriguing Michele, while Alexandros Tsilogiannis sang the role of Luigi with

total conviction, if at times he struggled with the demands Puccini makes on

the tenor’s uppermost range. Maria Kozlova gave a credible interpretation of

the role of Giorgetta, and Stuart Laing (Tinca) and Andrew Tipple (Talpa)

captured the weary laissez-faire of the poverty-stricken dock-workers.

A double bill of Holst and G&S completed the trio of Short Works

(23rd October). In the latter’s Trial by Jury, Nicholas

Morris was a fittingly aloof ‘Learned Judge’, well-served by his

distinctive court Usher, Ashley Mercer. Irish-Canadian soprano, Johane Ansell,

gave a confident, accomplished performance as ‘The Plaintiff’, while

Italian-Canadian tenor Riccardo Iannello was a sympathetic ‘Defendant’.

Director Conor Hanratty moved the ensemble of bridesmaids and gentleman of the

jury neatly around the small stage, and the deft choreography contributed to

the fluency of the performance. Holst’s The Wandering Scholar

preceded the G&S carry-ons, but despite strong singing from Gavan Ring (as

the disreputable Father Philippe) and Peter Davoren as the scholar Pierre who

thwarts the Father’s plans for seductions and assignations, the work failed

to convince. The married couple, Louis and Alison, were purposively sung by a

clear-voiced Jamie Rock and bright-toned Chloe Morgan respectively, but this

medieval bedroom farce felt rather lightweight.

Looking ahead, WFO will follow its acclaimed 2012 production of Delius’s

A Village Romeo and Juliet with the composer’sKoanga in

2015, partnered by Mascagni’s Guglielmo Ratcliff and Ferdinand Hérold’s Le Pré aux clercs. So, as usual, there

should be something for everyone.

Claire Seymour

Casts and production information:

Mariotte: Salomé

Salomé, Na’ama Goldman; Hérodias, Nora Sourouzian; Hérode, Scott

Wilde; Iokanaan, Igor Golovatenko; Page, Emma Watkinson; Le Jeune Syrien,

Eamonn Mulhall; First Soldier, Nicholas Morris; Second Soldier, Jorge

Navarro-Colorado; director, Rosetta Cucchi; conductor, David Angus; set

designer, Tiziano Santi; costume designer, Claudio Pernigotti; lighting

designer, DM Wood; choreographer, Vittorio Colella; stage manager, Conor

Murphy.

Cagnoni: Don Bucefalo

Don Bucefalo, Filippo Fontana; Rosa, Marie-Ève Munger; Il Conte di

Belprato, Matthew Newlin; Agata, Jennifer Davis; Giannetta, Kezia Bienek;

Carlino, Peter Davoren; Don Marco, Davide Bartolucci; Supernumerary, Michael

Conway; director, Kevin Newbury; conductor, Sergio Alapont; set designer, Vita

Tzykun; costume designer, Jessica John; lighting designer, DM Wood;

choreographer, Paula O’Reilly; stage manager, Erin Shepherd.

Puts: Silent Night

German Side: Nikolaus Sprink, Chad Johnson; Anna Sørenson, Sinéad

Mulhern; Lieutenant Horstmayer, Philip Horst; Kronprinz, Alexandros

Tsilogiannis; Scottish Side: Jonathan Dale, Alexander Sprague; William Dale,

Ian Beadle; Father Palmer, Quentin Hayes; Lieutenant Gordon, Gavan Ring;

British Major, Koji Terada; French Side: Lieutenant Audebert, Matthew Worth;

Ponchel, Quirijn de Lang; the General, Scott Wilde; Madeleine Audebert, Kate

Allen; Gueusselin, Jamie Rock; Supernumeraries: Sean Banfield, Neil Banville,

Leonard Kelly, Fran O’Reilly; director, Tomer Zvulun; conductor, Michael

Christie; set designer, Erhard Rom; costume designer, Vita Tzykun; lighting

designer, DM Wood; fight director, James Cosgrave; stage manager, Theresa

Tsang.

Wexford Festival Opera, 22nd October — 2nd

November 2014

![Na'ama Goldman as Salomé [Photo by Clive Barda]](http://www.operatoday.com/Na%E2%80%99ama%20Goldman%20in%20Salom%C3%A9%20by%20Antoine%20Mariotte%20%E2%80%93%20Wexford%20Festival%20Opera%202014%20%E2%80%93%20photo%20by%20Clive%20Barda.png)