23 Jul 2015

Montemezzi: L’amore dei tre Re

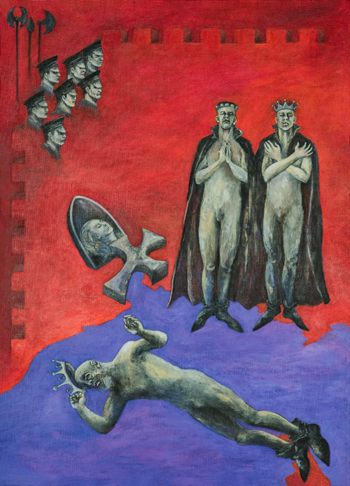

Asphyxiations, atrophy by poison, assassination: in Italo Montemezzi’s L’amore dei tre Re (The Love of the Three Kings, 1913) foul deed follows foul deed until the corpses are piled high.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

The doors at The Metropolitan Opera will not open to live audiences until 2021 at the earliest, and the likelihood of normal operatic life resuming in cities around the world looks but a distant dream at present. But, while we may not be invited from our homes into the opera house for some time yet, with its free daily screenings of past productions and its pay-per-view Met Stars Live in Concert series, the Met continues to bring opera into our homes.

Music-making at this year’s Grange Festival Opera may have fallen silent in June and July, but the country house and extensive grounds of The Grange provided an ideal setting for a weekend of twelve specially conceived ‘promenade’ performances encompassing music and dance.

There’s a “slide of harmony” and “all the bones leave your body at that moment and you collapse to the floor, it’s so extraordinary.”

“Music for a while, shall all your cares beguile.”

The hum of bees rising from myriad scented blooms; gentle strains of birdsong; the cheerful chatter of picnickers beside a still lake; decorous thwacks of leather on willow; song and music floating through the warm evening air.

Asphyxiations, atrophy by poison, assassination: in Italo Montemezzi’s L’amore dei tre Re (The Love of the Three Kings, 1913) foul deed follows foul deed until the corpses are piled high.

In Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges the King of Clubs, the ruler of an imaginary kingdom, tries to cure his son’s hypochondria with laughter. In Montemezzi’s vicious melodrama a blind king, Archibaldo menacingly guards his son’s wife from her former lover: there is none of Prokofiev’s colour, fairy-tale and satire, just abundant black fiendishness and slaughter.

Written in 1913, L’amore dei tre Re is a rich amalgam of musical influences: Wagner, Debussy, Puccini and Strauss — and the soaring melodic lines also recall the bel canto idiom of the early nineteenth century. The libretto (by Sam Benelli, based on his play of the same title) bears the heavy imprint of both Pelléas and Mélisande andTristan und Isolde, with, in the closing moments, a dash of Romeo and Juliet thrown in. But, Montemezzi whips up a psychological maelstrom more than equal to any of his operatic predecessors — and, in a matter of only 95 minutes. It’s surging, heady stuff — but not without musical sophistication, as Opera Holland Park confirmed in this splendid revival of Martin Lloyd-Evans’s 2007 staging.

The action takes place in the blind King Archibaldo’s castle following his occupation of the kingdom of Altura. (Archibaldo alludes to the figure of Otto the Great, who was Saxon King from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973, and who greatly extended his kingdom and power through foreign invasions and strategic marriages, conquering the Kingdom of Italy in 961.)

Princess Fiora of Altura has been forcibly wed to Archibaldo’s son, Manfredo; with the latter away at war, Archibaldothreatens and imprisons Fiora to prevent her meeting with her former betrothed, Avito. Needless to say, love finds a way … and learning that Fiora has been unfaithful to Manfredo, the King demands the name of her lover. When she refuses he strangles her and then orders her body to be borne to a tomb. Convinced that the secret lover will be unable to resist bidding his beloved a final passionate farewell, Archibaldo laces Fiora’s lips with lethal venom. True to form, Avito does return; but so does Manfredo, and both lover and husband succumb to the poison’s virulent potency.

This neo-medieval verismo, in which the distance of the Dark Ages shrouds the violence in patina of mystery, reaches extremes of psychological melodrama and emotional tension. Director Martin Lloyd-Evans and designer Jamie Vartan make the sensible decision to ignore the medievalism and minimise the set. They place an imposing constructivist concrete block centre-stage, with sloping ramps spanning the wide platform, and perilous stairways creating upper levels. The latter are sensibly used to raise the singers above the enlarged, resplendent and myriad-voiced forces of the City of London Sinfonia who project the relentless score (an almost unalleviated forte or louder) with power and passion. The effect is a visual echo of the monochrome, gravity-defying stairways of Escher’s lithographs, where those who live among each other occupy different planes of existence.

There are few gimmicks but many nice details, as when Archibaldo’s attire becomes increasingly more military as if to demonstrate the growing strength of his dictatorial grip and his monomaniacal ruthlessness. The grey is relieved only occasionally; but tellingly, when Fiora’s white silk veil — which Manfredo has asked her to wave as a sign of her love as he departs — billows from the height of the staircase and is embraced by Avito on the ground below. After Fiora’s death this veil becomes a ribbon of black. The reference to Mélisande’s luxurious hair in which Pélleas is enveloped is obvious, but deft. And, to keep the historical context in our minds — both that of the medieval past and the era of post-unification Italy when the opera was composed — two chorus members daub the castle walls with name of the 1920s anti-fascist resistance movement: ‘Giustizia e Libertà’.

It was only at the end of the opera as the chorus stirred themselves to revolutionary action and Fiora lay on a hospital trolley draped with the tricolour bandiera d’Italia that the focus seemed to turn a little too far from the private towards the political. I wasn’t sure, either, whether in the closing moments it was necessary for the masses, led by Archibaldo’s Italian guard Flaminio, to actually pull the trigger on their oppressor: we are left with the echo of gun-shot rather than the pathos of a blind tyrant with a pistol poised at the back of his head. Moreover, Archibaldo’s assassination is a directorial addition. In the libretto, Archibaldo enters the tomb and, finding Manfredodesperately kissing the infected lips of Fiora, assumes that he has trapped the guilty lover. When he discovers the truth, he wraps his arms about the body of his dying son, and it is the sightless old King’s lament with which the opera ends: ‘Ah! Manfredo! Manfredo! Anehe tu, dunque, Senza rimedio sei con me nell’ombra! Manfredo! Manfredo!’ (Ah! Manfredo! You too, then, with no hope of remedy, are with me in the shadows!).

As the focus for the violent passion of the ‘three kings’ — Avito, Manfredo and Archibaldo — and the catalyst of the triple tragedy, Fiora is also the opera’s single female role. Natalya Romaniw was more than up to the challenges and walked off with the vocal honours, though there was strong competition. The smooth arches of Montemezzi’s languorous melodic lines were excellently projected with no sign of a lessening of stamina. Romaniw’s tone was thrilling and radiant: but she was able to capture both Fiora’s sensuousness and her more ethereal delicacy — for upon her death the male chorus ask: ‘Who makes the lily, which has now come fall! The spring was killed among the flowers!’ (‘Chi ci rende il giglio, che venuto è ormai l'autunno! La primavera fu uccisa tra i fiori!’)

Initially I was not entire convinced by the supposedly all-consuming desire of Fiora and Avito, despite the erotic embraces on stage. Joel Montero’s characterisation of Avito was slightly one-dimensional to begin with but he found a true Italianate sound of great sweetness in the Act 2 duet and later a heroic, noble ring. His closing monologue — ‘Fiora, Fiora. È silenzio: siamo soli.’ (Fiora, Fiora. All is silent, we are alone.) — was captivating. Overcome by emotion, this Avito seemed genuinely close to death when he staggered from the bitter Manfredo and asked, ‘What do you want? … Can you not see that I can scarcely speak?’ (‘Che vuoi tu? Ma non vedi ch'io non posso quasi parlare?’)

Simon Thorpe used his lyrical baritone particularly well in the calamitous final scene; his tone was well-focused, revealing Manfredo’s humanity. As the blind patriarch, the American-Russian bass Mikhail Svetlov, reprised his role from 2007. This was a terrifying, threatening but mesmerising portrait: Mussolini meets a demented Arkel. In Act 1, Svetlov’s generous, dark-toned voice was occasionally covered at the bottom by the orchestra — one of perils of an open pit — but whenever on stage Svetlov was never less than utterly commanding. His convincing depiction of a blind man showed real dramatic intelligence: his infirmity added poignancy but also malignancy to his assertions of power. He paced the portrayal well too: we can see from the start that Archibaldo is insanely fanatical, but Svetlov slowly released his repressed, self-destructive desire for Fiora. This toxic lust culminated in a chilling and ferocious throttling: Archibaldo slumped over Fiora’s body in post-coital exhaustion, then — when discovered by Manfredo — brusquely kicked her dead body aside. Aled Hall also recreated his 2007 role and was excellent as Flaminio, pushing what is a fairly minor role to the centre of the drama.

Under Peter Robinson’s baton, the City of London Sinfonia surged with turbo-thrust towards a perennial precipice, much like the protagonists’ pulsing heartbeats. The score stabbed like a sword, and the outré harmonies swerved unpredictably. But, despite the orchestral extravagance and extroversion, the details didn’t get lost in the impassioned outbursts.

L’amore dei tre Re is melodramatic and certainly not subtle. It wouldn’t take much for a staging to slip into the realms of caricature and farce, but this OHP production never strays near parody and as the sun set over South Kensington we were all enveloped by the growing darkness. It’s compelling stuff.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Fiora: Natalya Romaniw, Avito: Joel Montero, Manfredo: Simon Thorpe, Archibaldo: Mikhail Svetlov, Flaminio: Aled Hall, An Old Woman: Lindsay Bramley, Ancella: Jessica Eccleston, Una Giovanetta: Abigail Sudbury, Un Giovanetto: Timothy Langston, Una Vecchia: Lindsay Bramley, Voce Interna: Naomi Kilby; Conductor: Peter Robinson, Director: Martin Lloyd-Evans, Associate Director: Rodula Gaitanou, Designer: Jamie Vartan, Chorus Master: John Andrews. Opera Holland Park, Wednesday 22nd July 2013.

L’amore dei tre Re will be performed on 25, 28 and 30 July, and 1 August.