At any rate, whilst not every aspect might have been the ‘very best ever’ - how could it be? - all was of a very high standard, and much was truly

outstanding. I even began to think that the wretched ‘traditional’ Prague-Vienna composite version might for once be welcome; it was not, yet, given the

distinction of the performances, the dramatic loss was less grievous than on almost any other occasion I have experienced.

If Daniel Barenboim’s Furtwänglerian reading in Berlin in 2007

remains the best conducted of my life, there was nothing whatsoever to complain about in James Gaffigan’s direction of the score. It was certainly a far

more impressive performance than a Vienna Figaro last year, which led me to wonder

how much was to be ascribed to other factors, not least the truly dreadful production; perhaps, on the other hand, Don Giovanni is just more

Gaffigan’s piece. The depth and variegation of the orchestral sound was second, if not quite to none, than only to Barenboim’s Staatskapelle Berlin. This

was far and away the best Mozart playing I have heard in Munich. Even if the alla breve opening to the Overture were not taken as I might have

preferred, and certain rather rasping brass concerned me at the opening, I find it difficult to recall anything much to complain about after that; nor do I

have any reason to wish to try. Tempi were varied, well thought out, and above all considered in relation to one another. Terror and balm were equal

partners: on that night in Munich, we certainly needed them to be.

This was, I think, Stephan Kimmig’s first opera staging, first seen in 2009. I shall happily be corrected, but I am not aware of anything since. If so,

that is a great pity, for the intelligence of which I have heard tell in his ‘straight’ theatre productions - alas, I have yet to see any of them - is

certainly manifest here. There are, above all, two things with which an opera staging cannot survive: a strong sense of theatre and a strong sense of

intellectual and dramatic coherence. Equally desirable is, of course, at least something of an ear for music, and coordination between pit, voices, and

stage action seemed to me splendidly realised too.

A perennial lament of mine concerning Don Giovanni productions concerns refusal or inability to understand it as a thoroughly religious work.

Here, there is certainly some sense of sin; its relationship to atheistic heroism is, just as it should be, complex. And the reappearance of the

Commendatore and (excellent) chorus at the end, some, including the Stone Guest himself, in clerical garb, reminded us, without pushing the matter, that

authority is at least partly religious here. There are other forms of authority too - Don Ottavio’s ever-mysterious reference to the authorities perhaps

intrigues us more than it should, or perhaps not - and they are also represented: military berets, business suits, and so forth. A libertine offends far

more than the Church; and of course, the Church as an institution has always been many things in addition to Christian (to put it politely).

Katja Haß’s set designs powerfully, searchingly evoke the liminality of Da Ponte’s, still more Mozart’s Seville. The drama is not merely historical,

although it certainly contains important historical elements. But above all, there is a labyrinth - one I am tempted to think of as looking forward to

operas by Berg, even Birtwistle, perhaps even the opera that Boulez never wrote - in which all manner of masquerading may take place. Social slippage and

dissolution - above all the chameleon-like abilities of the (anti-)hero - need such possibilities, which are present here, in abundance, in a setting that

both respects traditional dramatic unities and renders them properly open to development. A warehouse, containers revolving, opening and closing, changing

and remaining the same, provides the frame. Yet we are never quite sure what will be revealed, languages of graffiti transforming, never quite cohering,

Leporello’s catalogue - and, more to the point, its implications - foreseen, shadowed, recalled. There is butchery - literally - to be seen in the

carcasses from which the Commendatore emerges. There is glitzy - too glitzy - glamour in the show Giovanni puts on to dazzle the peasantfolk; but it does

its trick, coloured hair and all.

And there is an Old Man, observer and participant, sometimes there, sometimes not. Everyman? The nobleman, had he outstayed his welcome, not accepted the

invitation? He is clearly disdained, even humiliated (what a contrast, we are made to think, almost despite ourselves, between his naked body and the

raunchy coupling - or more - around him). That is, when he is seen at all: and that is, quite rightly, as much an indictment of the audience as of the

characters onstage. Part of what we are told, it seems, is that this is a drama of the young, who have no need of the elderly. Not for nothing, or so I

thought, did Alex Esposito’s Leporello exaggerate his caricatured sung response to Giovanni’s elderly women.

It is, then, an open staging: suggestive rather than overtly didactic. In a drama overflowing with ideas, that is no bad thing at all. Coherence is,

whatever I might have implied above, always relative; the truest of consistency will often if not always come close to the dead hand of the Commendatore.

For this was a staging that had me question my initial assumptions: again, something close to a necessity for intelligent theatre. (I assume that the

bovine reactions from a few in the stalls were indicative of a desire for anything but.)

If religion lies at the heart of the opera, too little acknowledged, perhaps at least a little too little here too, then so does sex. Sorry, ‘Against

Modern Opera Productions’, but there you have it; this really is not an opera for you, but then what is? Don Giovanni and Don Giovanni ooze -

well, almost anything and everything you want and do not want them to. They certainly did here, which is in good part testament to this superlative cast.

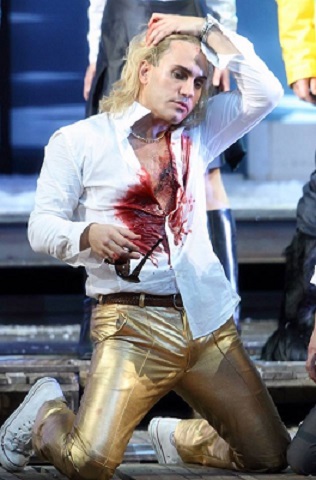

Erwin Schrott’s Giovanni may be a known quantity - I have certainly raved about it before, more than once - but it was no less welcome and no

less impressive for that. ‘Acting’ and singing were as one. He held the stage as strongly as I have ever seen - which means very strongly indeed - and his

powers of seduction were as strong as I have ever seen - which means, as I said… His partnership with Esposito’s Leporello was both unique and yet typical

of the dynamically drawn relationships between so many of the characters on stage. Leporello was clearly admiring, even envious of his master; their

changing, yet not quite, of clothes and identities was almost endlessly absorbing its erotic, yet disconcerting charge. Esposito brought as wide a range of

expressive means to his delivery of the text as any Leporello, Schrott included, I remember. Their farewell was truly shocking, Giovanni picking up his

quivering servant from the floor, kissing him for several spellbinding seconds, then wiping his mouth clean on his sleeve and spitting contemptuously on

the floor. It was time finally to accept the Commendatore’s invitation, issued with grave, deep musicality by the flawless, excellent Ain Anger.

I had seen Pavol Breslik as Don Ottavio before. There could have been no doubting the distinction of his performance in Berlin, under Barenboim, although neither

artist was helped by the non-production of Peter Mussbach. Here, however, Breslik presented, in collaboration with the production, perhaps the most

fascinating Ottavio I have seen - and no, that is not intended as faint praise. This was a smouldering counterpart to Giovanni, unable to keep his hands

off Donna Anna, and frankly all over her during her second-act aria. Their pill-popping - he supplied the pills - opened up all manner of possibilities,

not least given the frank sexuality of their, and particularly his, reactions. The beauty of Breslik’s tone, silken-smooth in his arias, added an almost Così fan tutte-like agony to the violent proceedings. In Albina Shagimuratova, we heard a Donna Anna of the old school: big-boned, yet infinitely

subtle, her coloratura a thing of wonder. Combined with the uncertainty of her character’s development - again, most intriguingly so - this was again a

performance both physically to savour and intellectually to relish.

So too was that the case with Dorothea Röschmann’s Donna Elvira. Her portrayal - Kimmig’s portrayal - would certainly not have pleased, at least initially,

those for whom this is in large part a misogynistic work. (It seems to me that they misunderstand some, at least, of what is going on, but that is an

argument for another time, and I am only too well aware that it is not necessarily a claim that I, as a man, should be advancing anything other than

tentatively.) Downtrodden, yet beautifully sung, in the first act, she nevertheless came into her defiant own in the second, above all through the most

traditionally operatic of means: sheer vocal splendour. What a ‘Mi tradì’ that was!

Eri Nakamura gave the finest performance I have heard from her as Zerlina, seemingly far more at home in Mozart than when I heard her at Covent Garden.

This was a Zerlina who both knew and did not know what she was doing - as a character, of course, not as a performance. And finally, Brandon Cedel’s

portrait in wounded, affronted, unconscious yet responsive masculinity proved quite a revelation: I do not think any Masetto has made me think so much

about his role in the drama. Nor can I think, offhand, of any Masetto so dangerously attractive - again, like Ottavio, in some sense an aspirant Giovanni,

but one still more incapable of being so. Morally, of course, that is to the character’s credit - but in this most ambiguous of operas, and in this most

fruitfully ambiguous of productions, one was never quite sure.

Mark Berry

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Don Giovanni

Don Giovanni: Erwin Schrott; Commendatore: Ain Anger; Donna Anna: Albina Shagimuratova; Don Ottavio: Pavol Breslik; Donna Anna: Dorothea Röschmann;

Leporello: Alex Esposito; Zerlina: Eri Nakamura; Masetto: Brandon Cedel; Old Man: Ekkehard Bartsch. Director: Stephan Kimmig; Set Designs: Katja Haß;

Costumes: Anja Rabes; Video: Benjamin Krieg; Lighting: Reinhard Traub; Dramaturgy: Miron Hakenbeck: Chorus of the Bavarian State Opera (chorus master:

Stellario Fagone)/Bavarian State Orchestra/James Gaffigan (conduct0r). Nationaltheater, Munich, Saturday 23 July 2016.