And, where better to perform these exuberant burlesques than Wilton’s Music Hall - the earliest surviving Grand Music Hall, set in the historic East End of

London.

Founded by Clarke in 1994, Opera della Luna has garnered well-deserved praise for its zany, zippy productions of operatta, comic opera and pantomime. Its

touring productions might notionally be ‘small-scale’ - performed by a troupe of actor-singers, without chorus, and accompanied by a small orchestral

ensemble - but there’s nothing ‘miniature’ about their ambition or their theatrical impact.

Charmed as we are by Offenbach’s full-scale operatic gems - such Les Contes d'Hoffmann, Orphée aux enfers and La vie parisienne - we often forget that he was the composer of some 90 operettas, more than 50 of which comprise just a single act. Sometimes

employing a full cast and chorus, elsewhere just two singers, they ranged from brief curtain-raisers to hour-long works, and reveal Offenbach’s delight in

farce, fantasy, cloak-and-dagger melodrama and the exotic.

Having striven in vain to get his work performed at the Opéra-Comique and other lyric theatres in Paris, in 1855 at the age of 35, Offenbach obtained a

license to open a small wooden theatre in the Champs Elysees - the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens - for the performance of one-act pieces typically

comprising a brief orchestral prelude followed by half-dozen or so solos and duets.

Railing against the dull pretentiousness of the operatic fare on offer at the Opéra-Comique, Offenbach promoted the tiny new theatre which had lain empty

between two trees on the Champs-Élysées, declaring: ‘In an opera which lasts only three quarters of an hour, in which only four characters are allowed and

an orchestra of at most thirty persons is employed, one must have ideas and tunes that are as genuine as hard cash.’ The same might be said of a modern-day

independent opera company - particularly in the absence of much ‘hard cash’ in the form of government support for artistic innovation and accomplishment.

Fortunately, Clarke is a cornucopia of ideas and theatrical masterstrokes. These two productions overflow with a glut of side-splitting gimmicks and gags.

The guffaws came thick and fast from the first, and did not stop. Clarke appreciates the affection with which Offenbach lays bare human eccentricities,

delusions and shortcomings. And, with a knowing nudge-wink which steers just the right side of vulgarity and excess, the director shows that he is

genuinely fond of these preposterous characters while at the same time nailing their bizarre flaws and foibles.

Croquefer

lampoons the violent immorality of the Crusades and sends up the arrogant affectations of medieval knighthood. Croquefer, ‘an immodest and faithless

knight’, has imprisoned Peasblossom, the daughter of his arch-enemy, Rattlebone. Their enmity has lasted for 23 years, financially ruining Croquefer and

depriving Rattlebone of arm, leg and tongue. Yet the latter remains a formidable, fear-inducing opponent, and Croquefer swallows his last weapon,

his beloved sword of Toledo, willing to accept an inglorious peace.

He orders his nephew, Headstrong, to guard their hostage. From her cell, Peasblossom recognises her guard as her beloved, and in their ensuing

love-duet they dream of running off together to Paris, imagining the delights they will enjoy at the Opéra. When Rattlebone arrives, Croquefer gives him a

choice: either he must permit Peasblossom to become Croquefer’s wife, or she will be killed. To evade this fate, Peasblossom and her amour poison the wine

and plot to murder the two adversaries, who are preparing to do battle. As the duel commences, the spiked drinks take effect and the sword-play is

interrupted for a swift dash to the thrones-turned-commodes. The violent purgation returns both Croquefer’s sword and Rattlebone’s tongue to their owners.

Differences are settled, Croquefer begs the audience’s indulgence - and the composer and librettist of the piece (or in this case, conductor Toby Purser)

are dragged off to the asylum!

The exposed bricks of Wilton’s, shrouded in wafting smoke, were a fitting back-drop for Croquefer’s dilapidated black tower which thrust up into a

storm-cloud strewn sky. Elroy Ashmore’s economical set designs had a Gothic edge - the arms of Croquefer’s throne curling out like grotesque hands - which

was complemented by Nic Holdridge’s bold lighting design.

Attired in leather breeches and sporting straggly black locks, Carl Sanderson made an immediate impression as the eponymous villain - self-important,

blustering and snarling, and equipt with a powerful tenor with which to lament the disintegration of his once-modish castle. He was aided with apt

ineptitude by Caroline Kennedy’s goofy Fireball - a cross-between the Artful Dodger and a circus clown. Eager to please, Kennedy shone with feverish

excitement as she peered through her telescope at the advancing Rattlebone, or lined up model Crusaders to imitate the beleaguered Croquefer’s diminished

army. The role of Fireball was originally composed for tenor, but Kennedy’s bright, sweet-toned soprano added freshness and air to the macho mix,

especially in the spirited Trio in which Headstrong’s eagerness for combat encourages Croquefer to renew his struggle against his foe.

Anthony Flaum’s lovely lyric tenor blended melodiously with Lynsey Docherty’s ingénue Peasblossom in their mock-dramatic love duet, as they scaled the

parodic heights of Offenbach’s comedic quotations from the hits of the day: Jacques Halévy’s La Juive and Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable and Les Huguenots.

Offenbach and his librettists cocked-a-snook at the Parisian authorities, evading the regulation forbidding more than four characters to appear on stage at

the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, by making their fifth character a mute who has sacrificed his tongue in his battles with the Saracens, and whose

contribution to the final quintet is limited to grunts and howls. One-armed and one-legged, Paul Featherstone staggered valiantly and lop-sidedly on

crutches, worn down by his over-size helmet and basket of placards as he sought to rescue his captive daughter. He and Sanderson had plenty of fun during

the pantomime-joust and sword-fights (choreography, Jenny Arnold), their perfectly timed faux-amateurism paradoxically highly polished and professional.

Known as the ‘Mozart of the Champs-Élysées’ and the ‘Napoleon of the operetta’ - and living in Paris under Napoleon III, a time when few in society, from

high to low, were really what they claimed to be - in some ways Offenbach’s whole life was a mask-wearing charade, and it’s no surprise that so many of his

characters do nothing but pretend to be what they are not. Offenbach’s The Isle of Tulipatan takes this role-playing to a new level of Wildean

absurdity. A double-en travesti farce of identity-crisis and quid pro quo, in which Nature triumphs over human presumption and

foolishness, this ‘bouffonerie’ takes place ‘at 25,000 kilometres from Nanterre, 473 years before the invention of the chamber pot’.

On the island of Tulipatan, King Cacatois XXII is unaware that his only son, Alexis - whose gentle disposition dismays him - is in fact biologically, his

daughter, disguised as such by his wife who refused to have another attempt at producing the heir to the throne so craved for by her husband.

Coincidentally, in order to avoid her child being conscripted into the army, Theodorine, the wife of the Duke’s steward, Field Marshall Rhomboid, has also

deceived her husband: their daughter, Hermosa, is in fact a boy, because the anxious mother could not bear the thought of losing him to military service.

Alexis and Hermosa are engaged to be married but their ignorance of their true sex spawns a string of misunderstandings until self-awakening and

gender-realignment ensue, to the satisfaction of all. But, not before a multitude of farcical opportunities which neither Offenbach nor Clarke neglect to

exploit to the full.

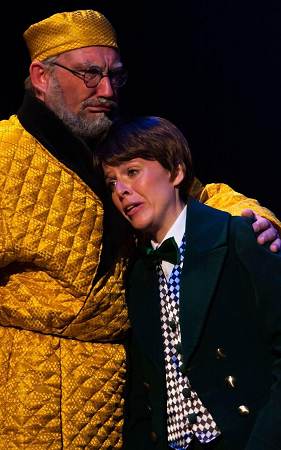

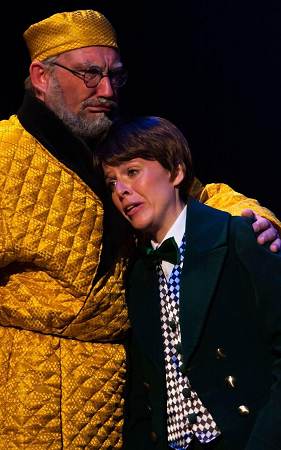

Carl Sanderson (Field Marshall Romboid) and Caroline Kennedy (Prince Alexis). Photo Credit: Jeff Clarke.

Carl Sanderson (Field Marshall Romboid) and Caroline Kennedy (Prince Alexis). Photo Credit: Jeff Clarke.

Caroline Kennedy’s emerald-frock-coated Prince Alexis delivered ‘his’ sentimental romance on the death of his pet bird with bell-like purity, touching

sincerity, not a hint of mockery and just the right amount of mawkishness. After the tomfooleries of Croquefer, Kennedy really showed her

dramatic range here using her voice and face most expressively. Her naïve curiosity when faced with the veracity of her femininity - ironically dressed in

a green and purple gown with black Doc Martins - was heart-winning.

Costumer Isobel Fellow supplemented the absurdities of the plot with costumes of garish complementary hue and Hermosa’s lurid pink frock with zebra

accessories made for a wonderfully incongruous clash with the swaggering sentiments of Hermosa’s military song. This was a terrific performance from Flaum

who, in drag, seemed to have taken inspiration from the late Les Dawson’s pantomime-dame arm-folding, hand-bag clutching and gurning grimaces.

Anthony Flaum (Hermosa) and Carl Sanderson (Field Marshall Romboid). Photo Credit: Jeff Clarke.

Anthony Flaum (Hermosa) and Carl Sanderson (Field Marshall Romboid). Photo Credit: Jeff Clarke.

Ashmore’s crenellated tower had been stripped of its battlements to reveal the crimson and gold flock-wallpaper of Rhomboid’s shabby-chic chateaux: a

fitting setting for Lynsey Docherty’s Theodorine who had clearly wandered off the set of Ab Fab and whose lugubrious inebriation would have given

Edina a good run for her money. Docherty’s insouciant indifference when she sweetened the Duke’s tea with a sugar-lump salvaged from his foot-bath was

priceless.

Carl Sanderson’s Field Marshall and Paul Featherstone’s Duke were once again a superb double-act: their performances were full of vitality. Featherstone

minced with ludicrous pomposity, resplendent in red velvet knickerbockers and diamond-patterned stockings. This was Alice in Wonderland meets

Oscar Wilde: the Knave of Hearts had somehow found himself in The Importance of Being Earnest. Featherstone may have ‘delivered’ his numbers - a

political satire with animal imitations, and a tongue-in-cheek ‘bacarolle’ - rather than sung them, but that didn’t lessen their spiciness or éclat.

Offenbach’s two scores may not be sparkling with musical invention - indeed, sometimes the music seemed to play second fiddle to the farcical comedy - but

the composer had an innate flair for heightening theatrical comedy with a catchy tune and a touch of musical twinkle, and the nine instrumentalists played

the score with evident enjoyment and vibrancy. Purser kept things whipping along, but judiciously allowed the cast to make the comic moments tell.

In any case, Clarke’s playful improprieties and droll rhyming couplets could turn even the most mundane melody into a memorable ear-tickler: “So here’s a

happy ending to our curious farce/ A tale of gender-bending in the upper class.” In this delicious double-bill, Clarke entwined madness and merriment, and

coated both with tenderness: quite simply, irresistible.

Claire Seymour

Jacques Offenbach: Croquefer, or The Last of the Paladins (1857)

Libretto: Adolphe Jaime and Etienne Trefeu

New English Version: Jeff Clarke - first performance July 23 2016

First performance: Theatre des Bouffes-Parisiens, February 12, 1857

Croquefer, Carl Sanderson; Fireball (Boutefeu), Caroline Kennedy; Headstrong (Ramasse-ta-Tête), Anthony Flaum; Rattlebone (Mousse-à-Mort), Paul

Featherstone; Peasblossom, (Fleur-de-Soufre), Lynsey Docherty.

Jacques Offenbach:

The Isle of Tulipatan

Libretto: Henri Chivot and Alfred Duru

New English Version: Jeff Clarke - first performance July 23 2016

First performance: Theatre des Bouffes-Parisiens September 13 1868

Cacatois XXII, Duke of Tulipatan, Paul Featherstone; Prince Alexis, his son, Caroline Kennedy; Field Marshall Rhomboid, Carl Sanderson; Theodorine, his

wife, Lynsey Docherty; Hermosa, his daughter, Anthony Flaum.

Director, Jeff Clarke; Conductor, Toby Purser; Set Designer, Elroy Ashmore; Costume Designer, Isobel Pellow; Lighting Designer, Nic Holdridge;

Choreographer, Jenny Arnold; Orchestra of Opera della Luna.

Wilton’s Music Hall, London; Friday 19th August 2016.