The Exterminating Angel

- a co-production with the Salzburg Festival, The Metropolitan Opera and

the Royal Danish Opera - was premiered to great acclaim at the 2016

Salzburg Festival, and most of the original stellar ensemble cast reprise

their roles here at Covent Garden. The libretto is the result of a long

collaboration between Adès and director Tom Cairns (according to the latter,

work on the text started in 2009), and is based upon Luis Buñuel’s 1962

film El ángel exterminador, in which the Mexican surrealist

lampoons a bunch of egocentric aristocrats who, gathering for a lavish

post-opera dinner party, find themselves afflicted by a surreal curse.

Despite the open door, they are inexplicably unable to leave the elegant

dining room. Even as their conditions deteriorate, and hunger and

desperation bring degradation, they cannot will themselves to cross the

threshold. Outside, the servants - who, blessed with a sixth sense that

scented the imminent danger, fled the mansion before the guests arrived -

are disinclined to rescue their social betters.

Buñuel injects the carnivalesque with a dose of Sartre and a dash of

Beckett. The inexact but excessive repetitions of his film reveal the

solipsism and arrogance of these vain bourgeoisie who accuse the servants

of being like rats deserting a ship, blaming them for their predicament

rather than acknowledging their own lack of will. The tone is abstract and

absurd, and the focus is on the ensemble rather than on individual

protagonists, as Buñuel exposes the sterility of the ritual-like behaviour

that structures daily life and social interaction.

Adès replaces Buñuel’s cinematic wit with musical parody and ingenuity, but

the musical structures, macro and micro, confirm the film’s exposure of

mankind’s obligation to repeat, even while the opportunity for individual

musical expression offers emotional ‘close-ups’. The clamour of church

bells which accompanies the audience’s arrival in the auditorium,

heralds the exterminating angel is heard again at the opera’s close. The

arrival of the guests is not only staged twice - as in the film - but is

also built upon a passacaglia form, as if the aristocrats are stuck on a

spiralling stairway, plummeting down into the abyss. In the final Act, as

the guests seat themselves around the burning brazier to devour their feast

of lamb (as Bach’s ‘Sheep May Safely Graze’ insouciantly but piquantly

infiltrates the score), they slip back into the obsequious small talk of their opening dinner party in a futile attempt to

re-establish social equilibrium, just as the quasi-waltz of Lucia’s Act 1

‘ragout-aria’ lurches distortedly into ear-shot.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Many of the moments of musical ‘stillness’ are built upon variation forms.

For example, the music of Blanca’s Act 1 aria - based on the children’s

poem ‘Over the Sea’ by Chaim Bialik - takes the form of variations on the

Ladino song ‘Lavaba la blanca niña’, intimating the vapid predictability of

post-dinner discourse. Many of the arias make use of strophic forms, and

frequent pedal points and ostinatos enhance the sense of overwhelming

stasis, as such repetitive devices musically embody habitual bourgeois

behaviour. Even the thundering interlude between Acts 1 and 2 - which

alludes to Buñuel’s Drums of Calanda (1964) and the filmmaker’s

native Calanda where, during Holy Week, the drums would resound for three

days and three nights - develops from a repeating rhythmic motif.

The opera’s score is an ingenious re-enactment of the past in the present.

But, in this work Adès’s characteristically and remarkably skilful parodic

eclecticism does more than remind us that our experience of music is

filtered through our memory of past musical experiences - from medieval

song to modernism; here, such musical echoes imply own our entrapment. So,

in Act II the ‘Fugue of Panic’ layers snatches of Strauss waltzes - and Adès imagines the latter as teasing and taunting,

‘Why don’t you stay a little longer? Don’t worry about what’s going on

outside’ - as the artifice of which the waltz is a symbol, and upon which

the guests’ sense of propriety is founded, is exposed as illusory.

There is no doubting Adès’s astonishing dexterity and perspicacity, nowhere

more evident than in his inventive handling of the large orchestral forces,

comprising piano, guitar and a whole arsenal of percussion. But, Buñuel’s

black humour seems diluted; the ‘laughs’ - judging from the audience

reaction at this performance - are primarily derived from recognition of

musical echoes, which ironically makes Buñuel’s point.

Anne Sofie von Otter. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Anne Sofie von Otter. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Buñuel, irritated by attempts to psychologically ‘un-pick’ his film,

retaliated, “I simply see a group of people who couldn’t do what they

wanted to - leave a room”. (Luis Buñuel, My Last Breath, trans.

Abigail Israel, 1984). Adès’s exterminating angel takes more tangible form.

It is a supernatural or mythical force which takes possession of the guests

and leads to what the composer describes as ‘an absence of will, of

purpose, of action’. Musically, the angel is embodied by the nightmarish

wail of the ondes martenot - the first time that Adès has used an

electronic instrument in his music. At moments when the characters find

themselves unable to act, or when they die, the return of this alien timbre

reinforces their entrapment; it is a ‘voice’ that Adès describes as

treacherously attractive and alluring, “like the sirens of Greek mythology,

saying: ‘Stay!’”

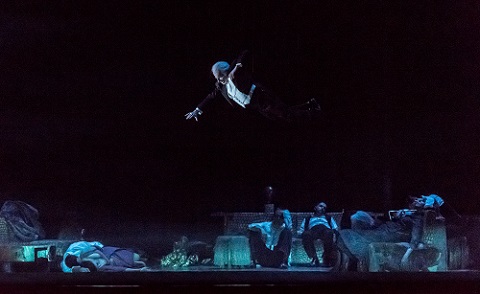

Tom Cairns directs the large cast with meticulous attention to detail while

Hildegard Bechtler’s set is sensibly sparse, dominated by an imposing,

square proscenium which swivels like a Kafkaesque plot, denying the

characters escape until the closing moments.

John Tomlinson (centre). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

John Tomlinson (centre). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The cast list reads like a family-tree of British singing-aristocracy, with

John Tomlinson and Thomas Allen relishing their character roles as fusty

doctor and lusty conductor respectively, while Christine Rice sings

beautifully as the latter’s wife, Blanca, and Sally Matthews wins our

sympathy as the bereaved Silvia de Ávila who in Act III pitifully cradles a

dead sheep in her arms believing that her ‘Berceuse macabre’ is a lullaby

for her son Yoli. Anne Sofie von Otter is brilliantly baffled as the old

battle-axe, Leonora Palma, slipping painfully from reality in her Act 3

aria, a number which sets Buñuel’s 1927 poem ‘It Seems to Me Neither Good

Nor Evil’ - a textual strategy that Cairns and Adès employ in several of

the ‘aria moments’ to convey the characters’ mental states.

Iestyn Davies and Sally Matthews. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Iestyn Davies and Sally Matthews. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

In a parodic Baroque mad aria, Iestyn Davies (as Francisco) becomes

wonderfully and woefully unhinged when he finds that there are no coffee

spoons with which to stir his post-dinner beverage, and his sister-fixation

with Matthews’ Silvia is convincingly conveyed - well as ‘convincing’ as

surrealism can be. Sophie Bevan and Ed Lyon are a touching pair of lovers,

Beatriz and Eduardo, remaining apart from the bourgeois vacuities and

choosing to commit suicide, in the score’s most delicate duet - a veritable

Liebestod, sung from within a suffocating closet - rather than to become

victims of the exterminating angel.

Sophie Bevan and Ed Lyon. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Sophie Bevan and Ed Lyon. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Though I couldn’t hear a word she sang, Amanda Echalaz is a luscious-toned

hostess, Lucia Marquesa de Nobile, and if Charles Workman, as her husband,

scales the tenorial heights with aplomb, then Audrey Luna tops him,

literally and figuratively, as Leticia Maynar - the opera singer whose

performance in Lucia di Lammermoor ostensibly prompts the original

gathering. Luna’s stratospheric peels are as ‘unreal’ as the ondes

martenot’s eerie howl and perhaps it is no coincidence that Leticia, the

so-called ‘Valkyrie’, who does not share the aristocratic pretensions of

the other diners, is aligned with the otherness of the exterminating angel;

for it is Leticia who first recognises their entrapment and it is she, at

the close, who, with her strange quasi-medieval chanson, enables their

‘release’.

Audrey Luna. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Audrey Luna. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

At the end of El ángel exterminador, the characters are ‘freed’ by

the re-enactment of the patterns of their imprisonment. The survivors go to

the cathedral to mourn those who have been lost and give thanks for their

own assumed emancipation, but as they seek solace in the passive church

rituals they find themselves entrapped once more, the cathedral doors

locked.

Adès and Cairns offer a different conclusion. The Chorus sing a line from

the Requiem mass over and over in a chaconne that, it seems, could go on

for ever. The score has no double-bar line to signal its close. The music

simply stops in the present, presumably to continue for eternity. And, so,

the opera is itself a ‘repetition’, or a ‘repetition with difference’,

reprising Buñuel’s film and creating a discursive space between the media

of film and opera.

Buñuel sometimes showed contempt for those who tried to pin down the

‘meaning’ of his films. A caption at the start of El ángel exterminador reads, ‘The best explanation of this film is

that, from the standpoint of pure reason, there is no explanation’ and the

film-maker declared, “This rage to understand, to fill in the blanks, only

makes life more banal. If only we could find the courage to leave our

destiny to chance, to accept the fundamental mystery of our lives, then we

might be closer to the sort of happiness that comes with innocence”. ( My Last Sigh)

But, it is difficult to ignore the search for ‘meaning’. One might look to

Buñuel’s own time: are the film’s aristocrats, marooned in their elitism

while the populace protest outside, a metaphor for Franco’s Spanish regime,

from which Buñuel was in exile in Mexico when he made the film? Is the film

a nihilistic statement by one who had witnessed the catastrophes of the

Spanish Civil War?

At the ‘close’ of Adès’s opera I found myself wondering to what extent he

was playing musical games and how far he was - hilariously and terrifyingly

- satirising our own lives.

Claire Seymour

Thomas Adès: The Exterminating Angel

Libretto: Tom Cairns, after Luis Buñuel and Luis Alcoriza

Leonora - Anne Sofie von Otter, Blanca - Christine Rice, Nobile - Charles

Workman, Lucia - Amanda Echalaz, Raúl - Frédéric Antoun, Doctor - John

Tomlinson, Roc - Thomas Allen, Francisco - Iestyn Davies, Eduardo - Ed

Lyon, Leticia - Audrey Luna, Silvia - Sally Matthews, Beatriz - Sophie

Bevan, Lucas - Hubert Francis, Enrique - Thomas Atkins, Señor Russell -

Sten Byriel, Colonel - David Adam Moore, Julio - Morgan Moody, Pablo -

James Cleverton, Meni - Elizabeth Atherton, Camila - Anne Marie Gibbons,

Padre Sansón - Wyn Pencarreg, Yoli - Jai Sai Mehta; Director - Tom Cairns,

Conductor - Thomas Adès, Set and costume designer - Hildegard Bechtler,

Lighting designer - Jon Clark, Video designer - Tal Yarden, Choreographer -

Amir Hosseinpour, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House (ondes martenot -

Cynthia Millar, piano - Finnegan Downie Dear), Royal Opera Chorus (Chorus

director - William Spaulding).

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Monday 24th April 2017.