August 31, 2017

The Queen's Lace Handkerchief: Opera della Luna at Wilton's Music Hall

The musical memory had been jolted by the waltzing strains of Roses from the South, the arrangement which had kept an otherwise forgotten operetta alive in the minds of Strauss’s contemporaries and subsequent audiences.

Written in 1880, six years after Die Fledermaus, The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief is, at times, melodious, funny and toe-tap inducing but is ultimately hampered by the convoluted flat-footedness of its ‘plot’. At Wilton’s, where last year I enjoyed the company’s fabulous Offenbach double bill , Opera della Luna, guided by their director Jeff Clarke, worked tremendously hard to make something of the long-winded absurdities of Heinrich Bohrmann-Riegen’s and Richard Genée’s libretto, but couldn’t quite pull it off.

Though Don Quixote has - in many a dramatic, balletic and operatic embodiment - frequently pounded the boards, the ‘ingenious nobleman’s’ creator, Cervantes, is a less-frequent theatrical visitor (though Mitch Leigh had a go at bringing Cervantes to life in his 1964 musical Man of La Mancha, in which, awaiting a hearing of the Spanish Inquisition, Cervantes and his fellow prisoners perform the knight’s escapades as a play within in a play).

Strauss and his librettists place Cervantes centre-stage in an intrigue, the political and amorous complexities of which defy comprehension and elucidation. So, to essay a back-of-an-envelope summary … the young King, a womanising gourmand, is being manipulated by the Prime Minister who encourages the under-age leader’s rakishness and ferments discord between the young monarch and his 17-year-old Queen. The Minister has clashed with Cervantes whose satirical play has provoked Sancho’s wrath, and led to the writer’s arrest. Donna Irene, Cervantes’ betrothed and the Queen’s confidante, enters the conspiracy, but is wrong-footed when the Queen develops an infatuation with the writer and writes a declaration of passion on her lace handkerchief, which she places between the pages of a Cervantes’ book. Medics, matadors and maniacs all wander into the dramatic, but somehow the knots are untied, Cervantes is released, and King and Queen are reconciled.

I didn’t ‘get it’ either … but, operetta is by nature not merely farcical but also satirical, and topicality is the key: so, although the operetta is ostensibly set in 16th-century Portugal, the ‘crisis of government’ it presents certainly strikes a raw nerve.

And, sensibly, judging that 16th-century Portugal and the Viennese waltz are not familiar bed-fellows, Clarke has discerned a contemporary relevance. In a recent interview , he explained: ‘What I believe the show is actually about is the Austrian court of the 1880s, with the young King clearly representing the young Crown Prince Rudolf. Many longed for the Emperor Franz-Josef to relax his ultra-conservative views. Rudolf espoused many enlightened liberal principles but was allowed little freedom to implement them by his unyielding father. His soon-unhappy marriage to Princess Stephanie of Belgium was regrettable and the root of his many scandalous affairs with young semi-aristocratic women. No-one in 1880 could have foreseen the tragic conclusion of Rudolf’s career when in 1889 he shot his lover Mary Vetsera before killing himself, in a suicide pact at his hunting lodge at Mayerling.’

So, Elroy Ashmore (sets), Wanda D’onofrio (costumes) and Nic Holdridge (lighting) whisk us off to 1880s Vienna, the straightforward design of skew-whiff painting-frame and hanging textiles indicating exterior or interior. The simplicity did result in a tendency for the singers to come to the fore of the stage and sing to the audience, rather than to each other, although as the dramatic complexities and comic interplay intensified, this was less of a hindrance.

Clarke has done his research: this production is based on a New York production of 1882, which opened the newly built Casino Theatre where it ran for 130 performances before touring successfully for over two years. Clarke mined the archives of the University of Wisconsin at Madison, and his version is ‘based on one of the four English versions of the show in that collection’. He commissioned a new small-orchestral arrangement from Francis Griffin, ‘based on the band parts in this collection, and on the manuscript orchestral score of the show which is now held in the Library of Congress in Washington DC’.

Clarke has also re-written the English libretto, though he might have been even more brutal in excising some of the lengthy, often dull, dialogue - after all, the plot’s illogical enough already, a few more non-sequiturs wouldn’t hurt.

While all operetta needs good singing-actors, Strauss presents perhaps greater vocal challenges than Offenbach - his waltzes are very difficult to sing - and on the whole Clarke has gathered together a sterling cast, who did their utmost to wring the best from text and score. Mezzo-soprano Emily Kyte’s King - an Orlofsky prototype - had copious confidence, allure and shine, though she was a bit under the note in the first act’s melodic peaks. But, she conveyed the King’s heedless self-absorption in the ‘Trüffel-Couplet’ - an aria in praise of a pastry - and generally strutted with panache.

Charlotte Knight, as Kyte’s Queen, acted with comic nous but didn’t have all the vocal arsenal required; Elinor Jane Moran had a bit more vocal substance as Donna Irene, and Katharine Taylor-Jones was a wise and stable presence as The Marchioness.

A be-whiskered Charles Johnston blustered his way with affecting charm as the pompous Prime Minister, and offered a skilled display in the G&S patter; Nicholas Ransley used his fairly light baritone to good effect as Sanchos. Tenor William Morgan displayed a good balance of warmth and bitterness as Cervantes.

One saving grace of the operetta is the dramatic potential of its ensembles, and Clarke and his singers didn’t miss a trick. The Act 2 opening was beautifully calmed by the three blended female voices; and the men made the most of their moment in the trio in which Cervantes uses his guile to trick the Minister and Sancho. If the Act 1 finale is repetitive and dull - and rather messy in execution here, with anxious glances being thrown in Purser’s direction - then the conclusion to Act 2 is and was a real delight.

There have been some fairly recent productions of The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief: Ohio Light Opera offered it in the summer of 2006, and the following year Staatsoperette Dresden performed a German language production which triggered Clarke’s interest.

I began this review by noting that Opera della Luna’s production was promoted as the first British performance of Strauss’s operetta; but, a little pre-performance research threw up a report in the Observer from 7th February 1937 that ‘the Alan Turner Opera Company add “The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief” to its list of annual first performances in England of Johann Strauss operettas’, with the ensuing observation that the work ‘represents Strauss more nearly at his worst than his best’, and that even with a new libretto and new lyrics, ‘1001 Nights was more entertaining’.

This hyperbolic denouncement is unfair on the work, and certainly doesn’t hint at the comic flair of Opera della Luna’s undertaking. But, it’s not entirely wide of the mark. So, all the more credit to Clarke and his cast, for if the Viennese frivolity was perplexing rather than pointed, then one’s feet were certainly stirred into toe-tapping motion by the waltz sequences. Opera della Luna squeezed what they could from the barmy machinations and intermittent musical interest.

Claire Seymour

Johann Strauss II: The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief

Opera della Luna: The King (Emily Kyte), The Queen (Charlotte Knight), The Prime Minister (Charles Johnston), Don Sancho (Nicholas Ransley), Don Cervantes (William Morgan), Donna Irene (Elinor Jane Moran), The Marchioness (Katharine Taylor-Jones), The Dancing Master (John Wood), Minister of War (Richard Belshaw), Minister of Justice (Ben Newhouse-Smith), Master of Ceremonies (George Tucker); director - Jeff Clarke, conductor - Toby Purser, set designer - Elroy Ashmore, costume designer - Wando D’Onofrio, lighting designer - Nic Holdridge, choreography - Jenny Arnold, Orchestra of Opera della Luna.

Wilton’s Music Hall, London; Tuesday 29th August 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Opera-della-Lunas-The-Queens-Lace-Handkerchief-featuring-The-Company.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief, Opera della Luna at Wilton’s Music Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Opera della Luna, the companyAugust 30, 2017

Véronique Gens: Visions from Grand Opéra

Here Gens presents extracts from Grand Opéra, reflecting her Tragodienne series of operatic arias. Visions is a stunner, rich and so rewarding that you want to rush out and hear each opera as a whole. This might be easier said than done, for some of the operas here aren't well known. Thus, all the more reason to get this recording because some real gems are included which you've almost certainly not heard done as well as they are done here. Véronique Gens is a great pioneer of French repertoire. So intoxicating is this recording that if you come to it as a taster, you could end up addicted.

Visions — visions of ecstasy, religious or romantic, exotic dreams and horrifying nightmares, virgins, nuns and heroines, plenty of variety, yet each piece a work of theatrical imagination Alfred Bruneau's Geneviève (1881) for example, from the cantata the young Bruneau dedicated to Massenet. The piece begins with a dizzying evocation of a storm. If this sounds Wagnerian, the scène lyrique that rises from it is decidedly French. "Seigneur ! Est-ce bien moi que vous avez choisi?", for she is just a shepherdess tending a flock. But the nation needs her, and she must put her mission above herself. From César Franck's Les Béatitudes (1879), a moment of quietude interrupted by the fierce scream that introduces the récit et air de Leonore from Louis Neidermeyer's Stradella (1837), its rhythms influenced by Rossini, enhanced by florid vocal frills. Benjamin Godard's Les Guelfes (1882) is represented by an orchestral prelude introducing a song describing Jeanne d'Arc's journey to Paris, her way lit by angelic harps.

From history to fantasy, Félicien David's Lalla Rookh (1862). French orientalism gloried in exotic images. This song is exquisite, its delicate perfumes warmed by the beauty of Gens' clear, pure expression. It also evokes the aesthetic of the Belle Époque. Thus a song from Henry Février's Gismonda (1919) a reverie with tolling bells where a solo violin shadows the voice.The protagonist is a nun, but longs, without much hope, for sensual love. Camille Saint-Saëns's arrangement of Étienne Marcel's Béatrix is altogether stronger stuff . Cello rather than violin, and mournful winds and a resolute vocal line. Béatrix knows that the love she knew will never return. "O Beaux Rêves évanouis ! Éspérances tant caressées!". This song is reasonably well known, and Gens does it beautifully.

This selection from Jules Massenet's La Vierge (1880) begins with an orchestral interlude. The Virgin Mary is about to die. The mood is subdued. But the Gates of Heaven open showing the Virgin a vision of Paradise. "Rêve infini, divine extase, l'éther scintille et s'embrase!" Gens voice glows, illuminated by rapture. After that explosive high, we return to the relative sedate Blanche from Fromental Halévy's La Magicienne (1885) who chooses the cloister, and to the prayer of Clothilde from Georges Bizet's Clovis et Clothilde (1857). Another song whose loveliness lies in its simplicity, again ideally suited to Gens's clear, pure timbre. .To conclude, L'archange from César Franck's Rédemption (1874) a vision of the End of Time. "L'homme rebelle n'obéit pas", and God, in anger chastises him. "Mais que faut-il pour son pardon? Après des siècles d'abandon , une heure de prière!" A rousing and rather cheerful end to a very good recording.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Visions.png

image_description=Véronique Gens : Visions

product=yes

product_title=Véronique Gens : Visions. dramatic arias from Bruneau, Franck, Nedermeyer, Godard, David, Février, Saint-Saëns, Massenet, Halévyand Bizet.

product_by=Véronique Gens, Münchener Rundfunkorchester.conducted by Hervé Nicquet.

product_id=Alpha 279 [CD]

price=$18.99

product_url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/album.jsp?album_id=2252642

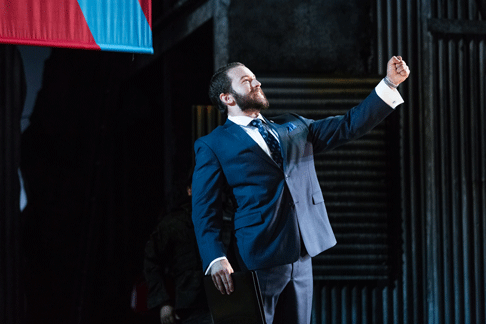

Glyndebourne perform La clemenza di Tito at the Proms

Robin Ticciati conducted the Glyndebourne Chorus and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, with Richard Croft as Tito, Alice Coote as Vitellia, Anna Stéphany as Sesto, Joelle Harvey as Servilia, Michèle Losier as Annio and Clive Bayley as Publio. Iain Rutherford’s semi-staging was based on the production by Claus Guth, with designs by Christian Schmidt.

With the orchestra pushed well back on the platform, the opera was performed in two areas, the fore-stage and a raised area behind the orchestra. Rutherford’s blocking made very effective use o the Royal Albert Hall. The remains of Schmidt’s sets, modern arm-chairs, clumps of corn and rather plastic-looking rocks, puzzled somewhat. The costumes were stylish modern dress, though somewhat drab in colour except for that of the actor playing Berenice, Tito’s lost love.

This was very much a modern-day production with contemporary mores, there was little of the classical nobility often associated with the work. Richard Croft’s Tito was wracked throughout with extreme emotion and his clemency was hard won, with some violence done to the musical line of the recitative (granted, this is not by Mozart but he must have approved of it). Similarly Vitellia and Sesto’s relationship was very physical, we first encountered Alice Coote and Anna Stéphany in a very compromising clinch.

Anna Stéphany made a very lithe, youthful Sesto, convincing in masculinity and very much suggesting Sesto’s youth, and the gap in ages between him and Alice Coote’s maturer Vitellia. Stéphany’s performance was similarly lithe, her slim mezzo-soprano voice offering us a combination of shapely line and vibrant passion. ‘Parto; ma tu ben mio’ was taken quite slowly in the opening section with great freedom in the phrasing, but Stéphany and the clarinettist really conveyed the music’s intensity whilst Sesto’s final aria, the rondo ‘Deh, per questo istante solo’ was beautifully shaped, rising to strong emotion at the end.

Alice Coote performs the role of Vitellia in Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment under conductor Robin Ticciati. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Alice Coote performs the role of Vitellia in Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment under conductor Robin Ticciati. Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Vitellia is a role that Alice Coote seems to have been born to play, a complex character whom we don’t quite love but can understand. Coote really brought out Vitellia’s conflict of emotions, and in each utterance we could see and hear the play of emotions across her face and her voice. Some of the role lies quite high for a mezzo-soprano, but Coote never made us feel she was going outside the role the extremes of range (high and low) were representative of the extremes of emotion. But there was also much quiet, beautiful singing; this Vitellia was more than just a scheming bitch. Coote crowned the performance with a stunning final accompanied recitative, where each word was strongly coloured, leading to a tormented account of ‘Non, piu di fiori’. This had Coote’s trademark flexibility of phrasing and use of rubato, but always in the service of heightening the emotion. And she was superbly partnered by the solo basset-horn. Interestingly I had previously seen Coote as Sesto, and wondered how many mezzo-sopranos have played both roles.

The only soprano in the cast, Joelle Harvey was a demure but strong-minded Servilia. Harvey showed that pure tone and beautiful phrasing could be combined with real strength of character. Servilia is one of the few admirable characters in the opera, and Harvey made it show. She was finely partnered by Michèle Losier’s Annio. Like Anna Stephany, Losier created Annio as a believable, rather intense and serious young man. And made him count as a character, rather than just a dry run for Sesto. Michèle Losier and Joelle Harvey made Annio and Servilia’s Act One duet profoundly touching.

Tito’s arias are some of the most conventional in the opera. Richard Croft was not unstylish, but his singing was very vibrant with a great sense of drama rather than classical poise. It was very much in those recitatives that he really made the character felt. Clive Bayley was a highly characterful and easily dislikeable Publio, definitely a career politician on the make. And Bayley sang Publio’s aria with vivid vigour.

Richard Croft performs the role of Titus in Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment under conductor Robin Ticciati Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

Richard Croft performs the role of Titus in Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment under conductor Robin Ticciati Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou.

One of the striking features of librettist Caterino Mazzola’s adaptation of Metastasio’s libretto (done to Mozart’s instruction), is the introduction of many duets, trios and ensembles. And Mozart’s use of them make the drama really progress. It was noticeable in this performance ow the cast used the ensembles dramatically. So that both trios told a real story, and the astonishing ensemble which concludes Act One was positively gripping.

The Glyndebourne Festival Chorus was on strong form, singing Mozart’s choruses with power and style. But, in the context of a stripped back staging their use of Peter Sellers-like hand choreography was somewhat puzzling.

Robin Ticciati conducted a lithe and lively account of the score, but he was not averse to slowing down and allowing highly expressive phrasing from the singers. The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment was on strong form, producing a nice mix of drama and sophistication.

Mozart’s penultimate opera can still sometimes seem something of a misunderstood ugly duckling, its reversion to opera seria an aberration after the trio of operas with Lorenzo da Ponte. The opera’s message of clemency is very much an Enlightenment concept which does not always sit well with modern directors. But Glyndebourne fielded a well balance cast, and all contributed to a performance which, musically at least, took the opera seriously and conveyed intense emotions with great style.

Robert Hugill

Mozart: La clemenza di Tito

Glyndebourne Opera at the BBC Proms

Sesto: Anna Stéphany, Vitellia: Alice Coote, Tito: Richard Croft; Annio: Michèle Losier, Servilia: Joelle Harvey, Publio: Clive Bayley

Conductor: Robin Ticciati, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment

Royal Albert Hall, London; Monday 28 August 2017

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Anna%20Stephany%20Proms%20Glyndebourne.jpg image_description=Prom 59: La clemenza di Tito, Glyndebourne Festival Opera and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment product=yes product_title=Prom 59: La clemenza di Tito, Glyndebourne Festival Opera and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: Anna Stéphany performs the role of Sextus in Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment under conductor Robin Ticciati at the BBC Proms.Photo credit: Chris Christodoulou

August 29, 2017

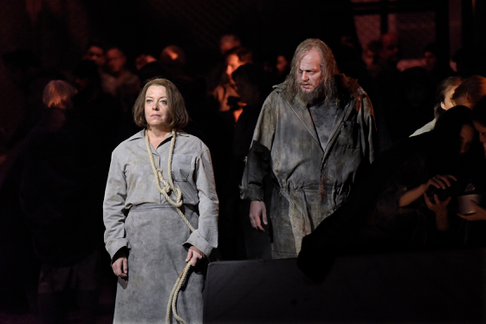

Rossini’s Torvaldo e Dorliska in Pesaro

Already before Torvaldo e Dorliska Rossini had three of his major comedies under his belt (La pietra del paragone, L’italiana in Algeri and Il turco in Italia) and two successful tragedies (Tancredi and Elisabetta).

But Torvaldo e Dorliska is a dramma semiseria — a horse of a quite different color. The genre can stretch finally into operas like maybe Don Giovanni and Rigoletto, but in Rossini’s oeuvre it did not engender any enduring Rossini masterpieces, as have comedy and tragedy — the 2015 Pesaro production of La Gazza Ladra, Rossini's only other semiseria, directed by Damiano Michieletto, definitively finished off its bid for masterpiece status.

Strict semiseria genre norms require a basso buffo, and Torvaldo and Dorliska obliges with the Duke of Ordow, played just now by none other than Nicola Alaimo, Pesaro’s recent William Tell. Mr. Alaimo is a performer of stature and of great presence, and is a powerful singer who evokes sympathy. These attributes confused this current Pesaro edition of,Torvaldo e Dorliska (a remount of its 2006 production directed by Mario Martone).

Salome Jicia as Dorliska, Dmitry Korchak as Torvaldo

Salome Jicia as Dorliska, Dmitry Korchak as Torvaldo

The Duke of Ordow is smitten by Dorliska, recently married to Torvaldo whom the Duke assumes his thugs have murdered. Not so. The wounded Torvaldo is taken into the Duke’s castle by its gatekeeper. Meanwhile Dorliska, abducted into the castle, is slapped around by the Duke to try to get her to marry him. Everyone rebels against the Duke for various reasons and he is led off to prison.

After all that we were quite confused as we had come to like Mr. Alaimo even though everyone on stage hated him.

Director Mario Martone and his designer Sergio Tramonti set this Polish tale somewhere with lots of thick foliage, all the better to mask his thugs as they came and went, and finally hide the revolutionaries as well. The setting had all the atmospheres of incipient Romanticism. But Rossini’s libretto was largely a farce of the type that plays best under bright lights.

Besides the un-Romantic brutal slapping of Dorliska Mr. Martone offered some extreme, un-Romantic schtick as well — Ormondo, the Duke’s lieutenant climbs a tree singing his aria, and falls out still singing (he was caught by his friends), and as the revolutionary movement gained momentum thousands of "Viva Rossini" leaflets rained down upon us from the auditorium's rafters.

The entire cast in the Act II finale

The entire cast in the Act II finale

As usual in Pesaro there were fine singers who created this evening of pure delight. Of particular note was young Georgian soprano Salome Jicia as Dorliska who raged and spat in secure Rossinian language, and Russian tenor Dmitry Korchak who delivered Torvaldo with aplomb though missing was an innocence and charm we might have liked in this young lover. Pesaro regular, bass Carlo Lepore convinced us as the duplicitous gatekeeper (we sympathized with his employer). A former participant in the Pesaro’s Accademia Rossiniana, baritone Filippo Fontana was the soldier who fell out of the tree singing.

The greatest pleasures of the evening were being in the Teatro Rossini, a typical Italian horseshoe theater of perfect size for minor Rossini, the able orchestral playing of the Orchestra Sinfonica G. Rossini under conductor Francesco Lanzillotta who found the real Rossini, and most of all it was a lot of fun to have the opportunity to explore the ideals and the potential of opera semiseria in this production of undeniable charm.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Duca d’Ordow: Nicola Alaimo; Dorliska: Salome Jicia; Torvaldo: Dmitry Korchak; Giorgio: Carlo Lepore; Carlotta: Raffaella Lupinacci; Ormondo: Filippo Fontana. Coro del Teatro della Fortuna M. Agostini; Orchestra Sinfonica G. Rossini. Conductor: Francesco Lanzillotta; Regia: Mario Martone; Scene: Sergio Tramonti; Costumi: Ursula Patzak; Luci: Cesare Accetta. Teatro Rossini, Pesaro, August 18, 2017.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Torvaldo_Pesaro1.png

product=yes

product_title=Torvaldo e Dorliska in Pesaro

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Nicola Alaimo as the Duke of Orlow, Salome Jicia as Dorliska [All courtesy of the Rossini Opera Festival]

August 28, 2017

Jakub Hrůša : Bohemian Reformation Prom

Hrůša started with the Hussite hymn Ktož jsú boží bojovníci (Ye Who Are Warriors of God), the men of the BBC Singers singing without accompaniment. Though we rarely hear the hymn as hymn, its tune is familiar. Smetana used it in Má vlast, quoting it in the section Tábor which we heard here, the town of Tábor being a Hussite fortress. Thus the quiet, tense introduction, developed through brass and timpani, which grows bolder as the hymn emerges. Triumphant climaxes and the hymn theme surges. But the Hussites were annihilated. Thus Blaník depicts the even earlier legend that St Wenceslaus, patron saint of Bohemia, will return to defend the nation. Smetana, writing at a time when Bohemia was ruled by the Hapsburgs, drew connections between the tenth-century saint and the Hussites. The strong angular themes in Tábor return in even greater glory in Blaník: massive drum rolls and crashing cymbals

In 1938, Czechoslovakia was annexed by Germany, with the implicit approval of Britain in 1938. Bohuslav Martinů's Polní mše, H. 279 Field Mass (1939) was written for Czech exiles fighting with the French against the Germans. Thus the strange instrumentation, with brass and percussion employed to suggest the idea of performance in battlefield conditions. Drum rolls, marching rhythms, trumpet calls and a chorus of male voices. But also piano and harmonium and a part for baritone soloist beyond the scope of an average amateur. Fortunately, in Svatopluk Sem, we heard one of the most distinctive voices in the repertoire. Sem is a stalwart of the National Theatre in Prague, well known to British audiences for his work with Jiří Bělohlávek who transformed the way Czech music is heard in this country. Sem delivered with great authority, imbuing the words with almost biblical portent. His text is based on poetry by Jiří Mucha, who was soon to marry Vítezslava Kaprálová. Her Military Sinfonietta (1937) would have worked well in this programme, though it doesn't include a part for choir.

In Martinů's Field Mass, the choir acts as foil to the soloist, voices in hushed unison, mass (in every sense supporting the individual. Though their music is relatively straightforward Miserere, Kyrie and psalm, this simplicity enhances the idea of mutual support, reflecting the relationship between piano with harmonium, voices and soloists surrounded by atmospheric percussion and brass. The version we heard at this Prom is the new edition by Paul Wingfield.

Somewhat less spartan instrumentation for Dvořák's Hussite Overture O67 (1883) though the hymnal purity of the anthem rings through clearly. The rough hewn faith of the Hussites doesn't support exaggeration. Full crescendos and running figures, (piccolo and flutes) flying free from the fierce "hammerblows"of the hymn. A glowing finale, from the BBC SO in full flow. The pounding rhythms of the Hussite hymn come to the fore in the Song of the Hussites from the opera The Excursions of Mr. Brouček to the Moon and to the 15th Century. Here the reference to the hymn is used for satire, contrasting the morality of the Hussites with the depravity of modern life, represented by the feckless, drunken Mr Brouček. To conclude this huge, ambitious programme,

Josef Suk's Prague op 26 (1904), in a tribute to Jiří Bělohlávek who made the BBC SO one of the finest Czech orchestras outside Czechia. The same goes for the BBC Singers who sing Czech pretty well. The piece was written at a dark time in Suk's life, after the death of his wife Ottilie and father-in-law Antonin Dvořàk. It connects to Suk's Asrael Symphony (op 27, 1905) and even to The Ripening (op 34, 1912-7). All three pieces deal with death, made almost bearable by faith, despite extreme grief.In Suk's Prague, the Hussite hymn makes an appearance as a symbol of something that lives on beyond temporal restraints., Suk seems to be surveying the city he loved, contrasting its history of struggle with his present. Perhaps, as he looked out on the castle, cathedral and the Rudolfinium, he could position his sorrow in a wider context. People die, but cultures remain. That's why I feel so strongly that the BBC Marketing term "Bohemian Reformation" is a crock. There''s a lot more to heritage than simplistic nationalism. Hrůša conducted Suk's Prague with such intensity, that the performance eclipsed all else in an evening filled with high points.

Jakub Hrůša's belated Proms debut but he is one of the most exciting conductors around, full of character and individuality. Though he's young, he's extremely experienced, and at a high level. In the UK, he's conducted at Glyndebourne and with the BBC SO and the Philharmonia, where he becomes Chief Guest Conductor next season. He is a natural in Czech repertoire, and a possible successor to Bělohlávek, whose memorial he conducted in Prague, but he's also very good in other material. Definitely a conductor to follow

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Jakub_HrOAa_c_Pavel_Hejnz_02.jpg

image_description=Prom 56: Jakub Hrůša with the BBC Symphony Orchestra

product=yes

product_title=Prom 56: Jakub Hrůša, Svatopluk Sem, BBC Symphony Orchestra, BBC Singers - Hussite Hymn, Smetana, Martinů, Dvořák, Janáček and Josef Suk. Royal Albert Hall, London, 25th August 2017

product_by=A review by Anne Ozorio

product_id=Above: Jakub Hrůša

Photo credit: Pavel Henjý

Wozzeck at the Salzburg Festival

And there’s more recent stuff, much more, mostly multi channel video and sound installations around the world that I won’t see

All of Mr. Kentridge’s disciplines come into play in his opera productions, providing this prolific artist a rich palate of expressive tools. Though basically it’s abstract black lines, and silhouettes, symbolic images, and fragmented squares (still or moving images or playing areas) on a stage face plane that is his hyperbolic canvas. It is one dimensional.

Given Mr. Kentridge’s prestige he works with only the most prestigious, i.e. rich opera companies, thus his productions are supplied with first rank artists, conductors and orchestras, and the most expert technical assistance.

Matthias Goerne as Wozzeck, Jens Larsen as the Doktor

Matthias Goerne as Wozzeck, Jens Larsen as the Doktor

Of his operatic oeuvre, Wozzeck is his masterpiece, the precision of the opera’s focus, and the velocity of dénouement make quick and pointed use of his techniques. We had little time to tire of them, and given the subject matter they were not trite. It was an artistic success of image to music.

The program booklet informed us that Berg’s Wozzeck was born of the first world war, and composed in the shadows of its human devastation, thus the most powerful of the progression of projected images that captivated our interest (while Buchner’s tragedy unfolded below) was a huge WWI gas mask (not shown in photos).

This Wozzeck therefore did not dwell on the accumulation of the heady human tragedies of Wozzeck, Marie and the Child, but on the plethora of Kentridge images that flowed to the accompaniment of baritone Matthias Goerne’s smooth, art-song style delivery of Wozzeck’s deceptions and delirium. Mr. Goerne in fact was the surrogate William Kentridge in this production — Mr Kentridge himself is always a central feature in his stagings.

A super, the puppeteer and puppet of the child in gas mask

A super, the puppeteer and puppet of the child in gas mask

Of very great effect was the Child represented by a puppet, an image laden with metaphoric, if hackneyed possibilities. Though in addition to dehumanizing the human expressionism of Berg’s domestic tragedy the puppet troubled us greatly. Puppets don’t sing, so who was going to sing the “hop hops" of the final image?

No one did, they were played by mallets in the orchestra, the words projected on the supertitle screen.

The putrid physical and human atmospheres of Berg’s opera were smoothed over by the flow of images. This same flow obliterated the independence of scenes, the accumulation of which generally lead to the overwhelming effect of Marie’s murder, Wozzeck’s suicide and the Child’s isolation.

The Vienna Philharmonic in the pit of the medium sized Haus für Mozart theater brought an overwhelming presence to Berg’s score. But the vaunted orchestral signposts were obliterated by the incessant flow of images. Moments when you ached to sink into Berg’s abstract musico-dramatic world rushed by so quickly you only reacted to them after the fact. Was this the intention of conductor Vladimir Jurowski, or was he a victim of the production?

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Matthias Goerne: Wozzeck; John Daszak: Drum Major; Mauro Peter: Andres; Gerhard Siegel: Captain; Jens Larsen: Doctor; Tobias Schabel: First Apprentice; Huw Montague Rendall: Second Apprentice; Heinz Göhrig: Madman; Asmik Grigorian: Marie ; Frances Pappas: Margret. Salzburger Festspiele und Theater Kinderchor; Concert Association of the Vienna State Opera Chorus ; Vienna Philharmonic; Angelika-Prokopp-Sommerakademie der Wiener Philharmoniker. Vladimir Jurowski: Conductor; William Kentridge: Director; Luc De Wit: Co-Director; Sabine Theunissen: Sets; Greta Goiris: Costumes; Catherine Meyburgh: Video Compositor & Editor; Urs Schönebaum: Lighting . Haus für Mozart, Salzburg, August 24, 2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Wozzeck_Salzburg1.png

product=yes

product_title=Wozzeck at the Salzburg Festival

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Matthias Goerne as Wozzeck, Asmik Grigorian as Marie, dead [All photos copyright Salzberger Festspiele / Ruth Walz]

August 27, 2017

Lear at the Salzburg Festival

There remain in my mind indelible images from the San Francisco performances. Ponnelle used a stage wide, brush-filled heath against a black void (an antique, under-stage hydraulic system was revived to vary heights of this floor). The storm raged with the bare pipes of the fly system in chaotic motion. And the rages of Mme. Dernesch’s Goneril remain a vivid memory as well. I know of no other productions of the Reimann Lear in the U.S.

In San Francisco it was sung in English, though this was before supertitles came into general use. Without a clear text in front of you the prodigious subtleties of the Reimann score were (dare-we-say) vaguely felt rather than dramatically understood.

Thus this Salzburg Festival revival of Reimann’s cold-war masterpiece, now with subtitles in both German and English, was a musical and dramatic revelation. It is a nearly precise reading of Shakespeare’s play, but in musical terms, and those chosen by composer Reimann are bleak and brutal and ugly. Like Zimmermann’s famed Die Soldaten (1965) Lear throbs with threat, fear and remorse. It is unrelenting, and there is no salvation.

Both operas respond mightily to Germany’s position as the epicenter of the cold-war, and to its enduring guilt for the two twentieth century world-wars.

Now we are in the twenty-first century, and most of us decline to bear the guilt of our fathers. Reimann’s Lear can now finally exist on purely artistic terms. It is a magnificent orchestral score that takes us on a journey into a human hell, an experience we can bear only with the protection of high art. It is not for the faint of heart, or art for that matter.

And for the Salzburg Lear there is no place more accommodating than Salzburg’s old riding school, the Felsenreitschule, its massive galleries carved into the solid cliff of granite that is the backdrop for this space now used as a theater. For Lear there is no more fitting orchestra than the magnificent forces of the Vienna Philharmonic, including a side gallery stuffed with massive additional percussion.

Michael Maertens as the Fool (speaking role) with Lear's knights (chorus and supers)

No longer considered a parochially German experience, it was staged by Australian theater and film director Simon Stone. Like Ponnelle in Munich the action occurred on a single platform, first it was a heath of fresh flowers, then it became a pure white slab with a pool of blood. It was staged as theater in the round, several hundred people sitting below the empty galleries behind the platform.

There followed one coup de theatre after another — the flowered heath was ruthlessly torn out by Lear’s knights; rain poured down for the duration of the storm; Mickey Mouse appeared on the stage; spectators behind the platform were torn out of their seats and thrown into the pool of blood; the hundreds of spectators sitting behind the platform, suddenly symbolic victims of war, were brutally driven out of the theater; a full-stage surround of white film cloth dropped to create a massive, heroic hospital space for Lear and Cordelia’s death.

I don’t think I’ve given too much away (and spoiled it for anyone) as it was a site specific event, surely impossible to re-produce elsewhere.

Lauri Vasar as the Duke of Glouchester in Mickey Mouse head cover

Cleveland Symphony conductor Franz Welser-Mõst urged and controlled rhythmic and harmonic contortions that flowed and over-flowed with ultimate Shakespeare’s cruelty. The stage resources equalled the pit resources in this production of massive size and daunting complexity.

Canadian born, British baritone Gerald Finley suffered willingly and mightily in a somewhat small scale, very sympathetic, human portrayal of Lear, Dresden Opera’s Evelyn Herlitzius again proved herself a singing actress of surpassing power as Goneril (she was Patrice Chéreau’s Elektra at the Aix Festival). Estonian baritone showed himself as an accomplished dancer in his vivid portrayal of the blinded Glouchester, and German counter-tenor Kai Wessel made great effect as Glouchester’s son Edgar, the tragedy’s only survivor.

The Salzburg Festival was obviously committed to making this an important theatrical and musical event. The assembled cast achieved this goal dramatically and vocally, and the production team arrived at its theatrical brilliance with amazing technical finesse.

Michael Milenski

August 22, 2017. Cast and production information above

Gerald Finley: König Lear; Evelyn Herlitzius: Goneril; Gun-Brit Barkmin: Regan; Anna Prohaska: Cordelia; Lauri Vasar: Graf von Gloster; Kai Wessel: Edgar; Charles Workman: Edmund; Michael Maertens: Narr; Matthias Klink: Graf von Kent; Derek Welton: Herzog von Albany; Michael Colvin: Herzog von Cornwall; Tilmann Rönnebeck: König von Frankreich; Franz Gruber: Bedienter; Volker Wahl: Ritter.

Konzertvereinigung Wiener Staatsopernchor, Weiner Philharmoniker.

Franz Welser-Möst: Musikalische Leitung;

Simon Stone: Regie

; Bob Cousins: Bühne

; Mel Page: Kostüme

; Nick Schlieper: Licht;

Christian Arseni: Dramaturgie. Felsenreitschule, Salzburg, August 23, 2017

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Lear_Salzburg1.png

product=yes

product_title=Lear at the Salzburg Festival

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Gerald Finley as Lear, Anna Prohaska as the ghost of Cordelia at the death of Lear [All photos copyright by the Salzburger Festspiele / Thomas Aurin]

August 26, 2017

Ariodante at the Salzburg Festival

Handel opera productions are famously fraught with troubling decisions — which voices to use, which gender to use for which voices, which dances to use from which opera. Sometimes decisions are made for you. Like, for example, Handel had no choice but to use the Covent Garden theater back in 1735 for his Ariodante, and to use an imposed roster of singers, and to use French choreographer Marie Sallé’s troupe of dancers.

The abstract story telling of the Handel operas indeed offer stage directors rich possibility for imagining context. For example the metteur en scène, Richard Jones, of the 2014 Aix Festival production of Ariodante illuminated its dramaturgical depths by placing the action within the fundamental Christian values (and confines) of the American Midwest.

But in Salzburg German stage director, Christof Loy, took everything at absolute face value -- it was Handel's opera as it was, through post-modern lens. As givens he had a producer (general director) of impeccable taste (Cecilia Bartoli) for the casting, one of the world’s foremost artists as his Ariodante (Cecilia Bartoli), and an unlimited budget for Salzburg’s splendidly equipped Haus für Mozart theater.

Nathan Berg (The King of Scotland), Kristofer Lundin (Odoardo), Christophe Dumaux (Polinesso), Sandrine Piau (Dalinda)

Nathan Berg (The King of Scotland), Kristofer Lundin (Odoardo), Christophe Dumaux (Polinesso), Sandrine Piau (Dalinda)

Like the 1735 production at Covent Garden, Mr. Loy’s production was not modest. It had multiple scene changes. A basic neoclassical room opened up from time to time to reveal elaborately painted Rococo scenes, and once it opened to reveal a shockingly huge room (it was elaborately forced-perspective architecture). As well there was an elaborately blank wall that descended mid-stage from time to time to obliterate all sense of physical location.

Though back in Aix Handel’s interpolated dance music became the erotic pole dancing of the U.S. prohibition era, the dances just now in Salzburg were simply highly stylized movements in mimic of the interlude ballets of French Baroque theater, the dancers dressed in French court dress of the time (including elaborate wigs).

Handel’s Ariodante was a castrato, Instead Mr. Loy’s Ariodante in Salzburg was a mezzo-soprano. He was Mme. Bartoli, and that provoked more than the usual play of gender confusion given this diva’s fame and repertory. It was a confusion easily solved by Christof Loy and Cecilia Bartoli as Ariodante reappeared after his failed suicide as partly female (see photo above), a transition that continued into the final scene where la Bartoli lost her beard as well (but she did, amusingly, maintain her exquisite trouser role imitation-male movement).

In turn, of course, Ariodante’s damsel Ginevra had donned boots and a jacket for the final scene with Ariodante to assume some genial male characteristics. The conceit quite evidently was that there was finally a union of male and female, at once completing human complexities of the two individual human psyches, and dramatically wrapping up the story in marital union. [In Aix Ginevra was last seen hitching a ride, alone, to Toronto.]

Cecilia Bartoli (Ariodante), Christophe Dumaux (Polinesso), dancers

Cecilia Bartoli (Ariodante), Christophe Dumaux (Polinesso), dancers

But finally it remained certain that the magnificent Bartoli had always been la Bartoli and never Ariodante.

Lost in the marvels of the Baroque’s psychological affects, elaborate Baroque vocal ornamentation, and the glories of the Baroque orchestral palate it did not matter where we were. And certainly it could not matter to the seven singers of the opera where they might find themselves either. Thus sometimes the actors were in simple contemporary dress, sometimes in current formal attire, sometimes in Baroque period costumes. What’s more, the Polinesso Lurcanio duel was fought in head-to-foot knightly armor. This play of costumes obliterated all sense of story and took us directly into the singers’ psyches.

Most of all stage director Loy indulged the famed indulgent smile of the Renaissance poet Lodovico Ariosto, the author of the stanzas of his epic Orlando Furioso from which the tale is taken. Like Ariosto we too, together with the evening's singers indulged these chivalric characters in their wishes and disappointments, their plotting and undoing, their anger and joy, their deceits and generosity, their weaknesses and strengths. Etcetera.

There was no place, and time stood still. This was our shared joy with the artists in this remarkable production.

Early music conductor Gianluca Capuano wrenched every possible nuance of tone from the truly splendid voices of Les Musicians du Prince, a new orchestra in the service of Albert II of Monaco founded by Cecilia Bartoli.

La Bartoli amazed us with magnificent ornamentation in Ariodante’s drunkenness and then spellbound us in his extended lament, only to amaze us even more more in her final aria of joy. American soprano Kathryn Lewec met her halfway, enthralling us in her extended laments and thrilling us in her joy. The villains of this operatic extravaganza were both French [!], Sandrine Piau made Dalinda vividly if blindly in love with Polinesso, charmingly and wittily sung — breathtaking coloratura — by countertenor Christophe Dumaux. Rolando Villazón brought huge presence to Ariodante’s brother Lurcanio, nailing his second act aria “Il tuo sangue, ed it tuo zelo” but later fought vocal distress. Canadian bass Nathan Berg suffered mightily and exulted greatly as the King of Scotland. His able leutenant was sung by Swedish tenor Kristofer Lundin.

Norwegian National Ballet choreographer Andreas Heise threw some very witty twenty-first century steps and poses into his sort of convincing facsimile of French Baroque dance. Set design by Johannes Leiacker, costume design by Ursula Renzenbring, and lighting by Roland Edrich provided the utmost in measured teutonic theatrical chic to this magnificent production.

Michael Milenski

August 22, 2017. Cast and production information above

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ariodante_Salzburg1.png

product=yes

product_title=Ariodante at the Salzburg Festival

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Cecilia Bartoli as Ariodante [All photos copyright by the Salzburger Festspiele / Marco Borrelli]

August 24, 2017

Cadogan Hall and soprano Nazan Fikret present Grenfell Tower Benefit Concert

BBC Radio 3’s Petroc Trelawny presents a concert in two parts on 17 September at 6pm at Cadogan Hall. The first half will include solo songs by Schubert, Schumann, Strauss and Quilter, followed by the Super Orchestra, conducted by Edward Gardner, accompanying Ailish Tynan and Christine Rice in the ‘Evening Prayer’ from Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel, an extract from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde sung by Stuart Skelton and Lee Bisset, the Quartet from Rigoletto, and the full company singing the Sanctus from Fauré’s Requiem.

Part Two will be launched with a performance of ‘I’ll Sing’ by award-winning composer Rebecca Dale, and will progress via Mozart’sCosì fan tutte, Le nozze di Figaro and Die Zauberflöte, to Puccini’s Tosca with Natalya Romaniw singing ‘Vissi d’arte’, and Keel Watson and Gweneth-Ann Rand performing ‘Bess, you is my woman now’ from Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. The pick of today’s most promising young singers will perform Vaughan Williams’ Serenade to Music.

This is a one-off event and everyone involved has given their services for free. To ensure that the funds raised by the Grenfell Tower Benefit Concert reach those that are in most need, the concert organisers and Cadogan Hall, in consultation with London Emergencies Trust, have decided to distribute the funds equally between Rugby Portobello Trust (Charity No 11000143) and Grief Encounter (Charity No 1101277) which focus specifically on helping the affected families with rehabilitation and looking to the future.

Singers will include: sopranos Lee Bisset; Francesca Chiejina; Samantha Crawford; Nazan Fikret; Janis Kelly; Louise Kemény; Anna Patalong; Gweneth-Ann Rand; Natalya Romaniw; Kirsty Taylor-Stokes; Ailish Tynan; Jennifer Witton; Lauren Zolezzi; mezzo-sopranos Katie Grosset; Anna Huntley; Maria Jagusz; Héloïse Mas; Christine Rice; countertenor Jake Arditti; tenors Luis Gomes; Robert Lewis; Stuart Skelton; Jack Swanson; baritones Gary Griffiths; Martin Häßler; Benedict Nelson; Alan Opie; Joseph Padfield; Ricardo Panela and bass-baritone Keel Watson.

They will be accompanied by several pianists including: Eugene Asti; Dylan Perez; Michael Pugh; Linnhe Robertson and Susanna Stranders.

Conductors Edward Gardner, David Angus, Douglas Boyd, Richard Hetherington, Matthew Morgan and James Sherlock, among others, will lead the Super Orchestra composed of players from the leading London orchestras including the Philharmonia, Royal Opera House Orchestra and Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

Further information can be found at: http://www.cadoganhall.com/event/grenfell-tower-benefit-concert-170917/

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Nazan%20Fikret.jpg

image_description=Grenfell Tower Benefit Concert, Cadogan Hall, 17 September 2017

product=yes

product_title=Grenfell Tower Benefit Concert, Cadogan Hall, 17 September 2017

product_by=

product_id=Above Nazan Fikret

Photo credit: Raphaelle Photography

August 23, 2017

Glimmerglass Being Judgmental

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, one of three characters in S/G was in attendance at all four main stage productions of the weekend, and of course was on hand for Wang’s enchanting 60-minute opera about her unlikely friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia. The sold-out house repeated a scenario of most other performances she attended: When Notorious RBG was recognized a smattering of applause built in intensity until it culminated in a vociferous standing ovation for the legendary jurist.

It was basking in the afterglow of this unique preshow moment that the curtain rose on Scalia/Ginsberg. Or rather didn’t rise, since there was no curtain. With Porgy and Bess having ended barely 60-minutes prior, the setting was of utmost simplicity: a black curtain isolating the apron of the stage, two easy chairs, a table and some stacks of books on the floor. And not only was that all that was needed, it freed director Brenna Corner to be endlessly creative coaching and blocking with her talented cast.

William Burden does not have quite the right look for the swarthy Scalia, but his acting more than compensated, capably suggesting the irascible personality. And, my, what singing! Mr. Burden has one of the most engaging lyric tenors in the business and composer Wang has crafted some flights of fancy above the staff that found him in excellent form. Bill is also a master of comic delivery and his patter and one-liners (Pure applesauce among them) landed every time.

Young Artist Mary Beth Nelson was picture perfect as Ginsberg, and she sang with virtuosic abandon. Wang has given his mezzo some extremely challenging florid singing all over the range and Ms. Nelson tossed it off with joyous flair and assured beauty of tone. In more reflective moments Mary Beth displayed a lovely range of vocal coloring that ranged from teasing to touching. Too, she was occasionally asked to cross over into a pop-blues delivery that she managed with such conviction and acumen, she prompted raucous shouts of approval from the house.

Joining these two highly accomplished performers, another Young Artist, Brent Michael Smith more than held his own as The Commentator. The composer devised this role as a sort of latter day Starkeeper (Carousel) who challenges and prods the Justices, and loosely ties matters together and keeps them moving forward. Mr. Smith not only has a substantial bass-baritone of considerable accomplishment, but he has maturity of delivery and a capacity for humor that make him a distinct asset to this or any other production. Just watch Brent fidget his way around a joking delivery or moonwalk his way across the stage, and you realize you can’t take your eyes off him lest you miss whatever inspired business he might do next.

Briefly put, The Commentator challenges Scalia to account for his rulings and seals the exits, amusingly done by leaning in two American flags at the top of the stairs to the audience level stage left and right. Scalia is challenged to pass three tests of vague definition and threat. Justice Ginsberg breaks in with an amusing entrance aria. When asked how she got past the sealed doors, she quips I have broken through a ceiling before.

Ginsberg first defends, then joins Scalia in his attempt to “explain himself” to The Commentator. Derrick Wang has exhaustively researched and annotated the many quotes that comprise his libretto and he has musicalized it with heart, levity, and occasional pastiche. At times there are so many clever musical quotes from famous arias tumbling over each other that it seems Derrick has not so much “composed” as “assembled” select passages.

But when called upon to bring his own important voice to the fore, Wang proves highly adept at crafting exceedingly attractive phrases that really take wing, buoyed by a harmonic palette that progress inevitably and agreeably. His angular writing for the more contentious exchanges remains vocally grateful and pungently accented with well-used dissonances. In a wondrously calculated penultimate number, Burden and Nelson vocalize We Are Different, We Are One, intertwining their poised phrases with ravishing tone and poignant delivery.

The composer first wrote the piece when Justice Scalia was still living, and for this occasion has revised it effectively to acknowledge his passing. As The Commentator escorts Scalia to his eternal home, he and Ginsberg exchange touching farewells. As the opera closes, Ruth hangs black crepe on Nino’s easy chair, evoking the tribute on his chair in the Supreme Court chamber.

Pianist Kyle Naig provided the accomplished accompaniment while conductor Jesse Leong kept the performance taut and assured. This was a perfect little jewel with which to end my enjoyable time at Glimmerglass, and it is always a treat to discover an accomplished new work by a living composer. Mr. Wang is young, he is talented, and if Scalia/Ginsberg is any indication, he will give us many more enjoyable evenings in the opera house before he is done.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Justice Scalia: William Burden; The Commentator: Brent Michael Smith; Justice Ginsberg: Mary Beth Nelson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/i-CnQzts8-X3.png

image_description=The Glimmerglass Festival Alice Busch Opera Theater. Designed by Hugh Hardy, the theater features unique sliding walls that open prior to performances and at intermission. Photo: Karli Cadel/The Glimmerglass Festival.

product=yes

product_title=

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: The Glimmerglass Festival Alice Busch Opera Theater. Designed by Hugh Hardy, the theater features unique sliding walls that open prior to performances and at intermission.

Photo © Karli Cadel/The Glimmerglass Festival.

American Masterpiece Conquers Cooperstown

Francesca Zambello has had considerable success staging the piece for other notable companies, and as evidenced by this richly detailed production, she has honed her insights to a finely polished interpretation. Ms. Zambello occasionally likes to flavor her operas with musical comedy flair and it does not go amiss here.

When appropriate, she enlisted choreographer Eric Sean Fogel to lighten up the mood with well-considered moves that emerge organically from exuberant revelers. Mr. Fogel’s staged movement was not only entertaining in its own right, but also greatly deepened the violent, tragic moments by providing good contrast. The only false move was the series of woozy cakewalk kicks at the climax of There’s a Boat That’s Leavin’ Soon for New York. It seemed out of character to have a weakened, drugged up Bess this frolicsome as she is slimily lured against her will by the pimping Sportin’ Life.

Ms. Zambello’s Catfish Row is peopled by a bustling, believable vitality that communicated a powerful sense of community. When David Moody’s scrupulously prepared chorus launched into their many big choral numbers, the Thrill-o-Meter needle jumped off the charts. Francesca has built strong individual characterizations with each cast member, and has nurtured relationships that are marked by honesty and clarity. The sense of directorial focus and readily comprehensible storytelling that emerge out of this rich mosaic of dramatic moments is nothing short of brilliant.

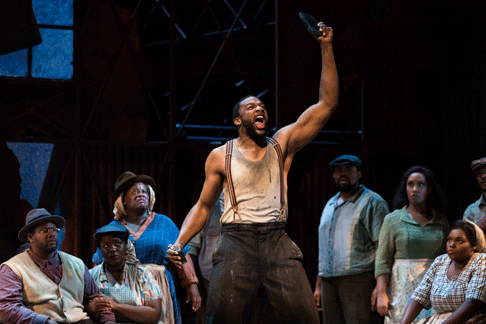

Frederick Ballentine as Sportin' Life with members of the ensemble

Frederick Ballentine as Sportin' Life with members of the ensemble

When Peter J. Davison’s imposing set is first revealed behind a front scrim, glowing hauntingly in Mark McCullough’s splendid lighting design, the audience burst into appreciative applause. Mr. Davison’s massive two story structure has rows of doors on each level, the upper balcony reached by a spiral staircase down right. This walkway extends to a large, barnlike building up left, with Porgy’s residence on ground level. A huge barn door, contained in the stage left wall, is opened and closed with import at key dramatic moments.

There is a wonderful chiaroscuro effect to the structures, the walls dotted and layered with rusting squares of sheet metal. For the storm scene, we are in a community hall with chairs and a table, defined as a huge wall flies in cutting the depth of the stage in half. Black plastic blows in the windows, augmented by Mr. McCullough’s threatening lightning. Sporadic dropping, banging and dangling of metal squares that had been “blown away” added fearful unpredictability to the chaotic effect.

The team has also “opened up” the action by flying in a partial wall and adding a bed to take us inside Porgy’s room. This allowed for a very focused private moment for both of the big duets. Another outstanding re-imagination was the conception of the Kittiwah Island setting as a neglected, gone to seed beachside amusement park. Sportin’ Life interrupts a holy roller baptism session to deliver his irreverent It Ain’t Necessarily So. To complete the dynamic look of the production, Paul Tazewell contributed the comprehensive costume design ranging from homely everyday attire, to Sunday-go-to-meetin’ finery, to splashes of garish color for Bess and Sportin’ life.

John DeMain kept things humming in the pit from the opening slashes of brass licks to the final stirring chorus. Under Maestro DeMain’s assured baton, this well-paced reading of Gershwin’s evergreen opera never sounded fresher. Having such a prodigiously talented cast sure didn’t hurt either.

Meroë Khalia Adeeb as Clara

Meroë Khalia Adeeb as Clara

Musa Ngqungwana is such a force of nature as Porgy, with a voice of such jaw-dropping beauty, richness, and power that he just might become a household name. Practice saying Ngqungwana now, because his star is only going to go higher and higher. Musa has such a big, beaming, lovable open face that you are not quite prepared for his ferocity when he is goaded to confront evil. His painful limping gait, his superstitious negative fantasies, his loneliness, his compassion, his utter devotion to Bess; there is no aspect of this complicated role that he does not serve with uncommon distinction. If I had to comprise a short list of the show’s highlights, it would be: Whenever Musa Ngqungwana is on stage.

Talise Trevigne makes an equally strong case for Bess, bringing star power to her well-considered interpretation. Her confident, glimmering soprano beautifully encompassed some of the work’s best-known melodies. Ms. Trevigne brought committed acting to the mix, and she found all the necessary extremes to this unstable, emotionally volatile character. Her singing is pliable and expressive in all registers and volumes, and she judiciously uses her chest voice to serve the desperate lower pleas in What You Want With Bess? Talise and Musa are wonderfully paired, exuding a good chemistry. Bess, You Is My Woman Now was so heart rending to see, so ravishing to hear that I thought the show might never get going again from the prolonged, cheering ovation at its conclusion.

Norman Garrett’s incisive, booming bass and lanky, lean, mean intensity made for a knockout performance as Crown. Frederick Ballentine’s serpentine take on Sportin’ Life was relentless in his bad-ass persona. Although Mr. Ballentine’s dancing was fleet of foot and his secure tenor pleased the ear, we never forgot that beneath the cynical comic overtones in the music, there was an unrepentant, unwavering criminal. Serena has one of the most overtly “operatic” solos, and Simone Z. Paulwell’s throbbing, well-schooled soprano made My Man’s Gone Now a plangent lament marked by velvet tone and utter commitment.

Norman Garrett as Crown

Norman Garrett as Crown

Meroe Khalia Adeeb has the most famous tune in the show, and her fresh, floated, silvery soprano made for a bewitching Summertime. Justin Austin’s honeyed baritone was well suited to the role of Jake. Chaz’men Williams-Ali has such a pleasing, vibrant tenor that it was a shame to lose him early on as the ill-fated Robbins. Happily, he snuck back in action later with a playful turn as the Crab Man. Judith Skinner struck just the right balance of brassy chest tones and cutting head voice to offer a well-rounded impersonation of Maria.

The enduring popularity of Porgy and Bess combined with the lovingly staged, magnificently performed production at hand deservedly made it a sell-out success. But I have to wonder, with all the stellar African-American talent filling the stage, where was the black audience? I wouldn’t even need to use all my fingers to count the African-Americans in the parterre seats at my performance. If opera is to sustain itself as an art form, it’s a question producers are going to have to answer. And if anyone can, my bet is on the resourceful Glimmerglass Festival.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Clara: Meroe Khalia Adeeb; Mingo: Steven D. Myles; Sportin’ Life: Frederick Ballentine; Jake: Justin Austin; Serena: Simone Z. Paulwell; Robbins: Chaz’men Williams-Ali; Jim: Nicholas Davis; Peter: Edward Graves; Lily: Gabriella H. Sam; Maria: Judith Skinner; Porgy: Musa Ngqungwana; Crown: Norman Garrett; Bess: Talise Trevigne; Detective: Zachary Owen; Policeman: Brent Michael Smith; Undertaker: Calvin Griffin; Annie: Briana Elyse Hunter; Nelson: Elliott Paige; Strawberry Woman: Jasmin White; Crab Man: Chaz’men Williams-Ali; Coroner: Chris Kjolhede; Scipio: Piers Shannon; Conductor: John DeMain; Director: Francesca Zambello; Choreographer: Eric Sean Fogel; Set Design: Peter J. Davison; Costume Design: Paul Tazewell; Lighting Design: Mark McCullough; Hair and Make-up Design: J. Jared Janas, Dave Bova; Chorus Master: David Moody

image=http://www.operatoday.com/KarliCadel-GGF17-Porgy-GenDress-4625.png

image_description=Talise Trevigne as Bess and Musa Ngqungwana as Porgy in The Glimmerglass Festival's 2017 production of The Gershwins' "Porgy and Bess." Photo: Karli Cadel/The Glimmerglass Festival

product=yes

product_title=American Masterpiece Conquers Cooperstown

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Talise Trevigne as Bess and Musa Ngqungwana as Porgy

Photos © Karli Cadel/The Glimmerglass Festival

Glimmerglass: Too Much to Handel?

Someone seemed to have lost about thirty minutes of music.

That does not mean the production was not exceedingly enjoyable. It most certainly was. But for Handel purists this opus may have seemed more like heavy hors d’oeuvres than a hearty main course. I am far from being a Xerxes scholar but as my seat mate said at intermission, “I enjoyed the A sections, but kept waiting for the B-A to follow.” Na, ja, I will stop talking about what I “think“ wasn’t there and focus very agreeably on what was.

Tazewell Thompson has directed the proceedings with invention, dimension and great attention to detail. Mr. Thompson finds wonderful variety in the interaction of his colorful characters, and moves the cast around with purpose and motivation. He has fostered an impetuous spontaneity in crackling confrontations, and invested more introspective musing with a brooding serenity. And it must said, he coaxed Arsamenes and Romilda into some pretty uninhibited smooching. Tazewell has been well served by his design team in creating a majestic sweep, and providing engaging visual interest that enlivened what could have been a static event.

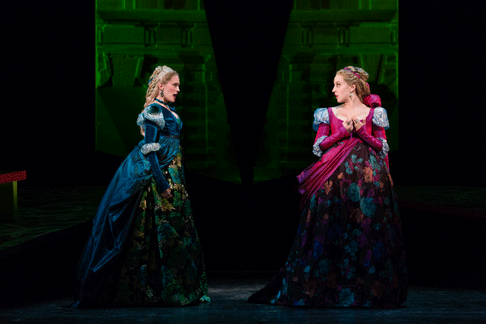

Katrina Galka as Atalanta and Emily Pogorelc as Romilda

Katrina Galka as Atalanta and Emily Pogorelc as Romilda

Set designer John Conklin has fashioned a modular concept of changeable beauty, constantly morphing configurations of floating, slightly raked platforms that are decorated with Pollock-like swirls and colors. Angled, disjointed hanging flats with architectural details in relief vie for position in Mr. Conklin’s settings, and he has anchored the whole with a floating, silver tree of life symbol. This crafty image first transforms into a piece of jealous iconography with blood red roots, then makes a cheeky commentary when it next appears, as completely upended as are Xerxes’ love relationships. The totality of his design look is underscored with popping, fire red accents of platform edges, stairs, or picture frames.

Sara Jean Tosetti has provided a truly sumptuous costume design, her lavish attire not only delighting the eye, but also tellingly defining the characters. With his accomplished lighting, Robert Wierzel was another conspicuous conspirator in the design team’s accomplishment with a sensitive, fine tuned plot of color washes and precisely calculated specials. I must also acknowledge that make-up and hair designers J. Jared Janas and Dave Bova provided another effective ‘look’ as they did for the entire Festival.

Conductor Nicole Paiement led a pulsating account of the score, brimming with inner rhythmic life and a good variety of appealing colors. Maestra Paiement found a captivating humanity in the score and inspired her accomplished soloists in turn to sensitive and propulsive vocalizing. The accommodating orchestra could not have been bettered with especial kudos reserved for the “Team Xerxes Continuo”: Katherine Kozak (Harpsichord), Ruth Berry (Baroque cello), Michael Leopold (theorbo, Baroque guitar), and Spencer F. Phillips (bassoon).

Emily Pogorelc as Romilda and John Holiday as Xerxes

Emily Pogorelc as Romilda and John Holiday as Xerxes

Counter tenor John Holiday, Jr. keeps going from strength to strength. Mr. Holiday was every bit the titular star the evening required, not only singing with haunting, piercing beauty, but also looking every inch the heroic persona. John’s handsome presence and resplendent vocalizing added up to a memorable achievement. The excitable and exciting Allegra de Vita gave him powerful chase with her fiercely sung Arsamenes. Ms. De Vita was adept at hurling out vigorous phrases replete with well-modulated coloratura, as well as possessing the skill to gently caress deeply felt legato passages.

Emily Polgorelc found a tragic nobility in Romilda and her elegant, poised vocal impersonation was an aural delight. As the sassy Atalanta, Katrina Galka regaled us with a fusillade of soprano pyrotechnics, her stylish, flexible soprano ringing out with aplomb. Bass Calvin Griffin was a sprightly Elviro possessed of charming vocal and theatrical gifts. Abigail Dock offered an empathetic, fluidly sung Amastris, her characterization enhanced by a most winning stage presence. Brent Michael Smith was the stalwart, solidly voiced Ariodates.

Maestra Paiement provided insightful program notes that informed us Handel deliberately eschewed the da capo format with some of the set pieces. Still, it often felt like something might be missing. Hey though, how often do I get to say that a Handel opera actually left me wanting more?

In the end, this exhilarating Xerxes was a summer delight so entertaining that it was over too soon.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Xerxes: John Holiday, Jr.; Arsamenes: Allegra de Vita; Elviro: Calvin Griffin; Romilda: Emily Polgorelc; Atalanta: Katrina Galka; Amastris: Abigail Dock; Ariodates: Brent Michael Smith; Conductor: Nicole Paiement; Director: Tazewell Thompson; Set Design: John Conklin; Costume Design: Sara Jean Tosetti; Lighting Design: Robert Wierzel; Hair and Make-up Design: J. Jared Janas, Dave Bova; Continuo: Katherine Kozak (Harpsichord), Ruth Berry (Baroque cello), Michael Leopold (theorbo, Baroque guitar), Spencer F. Phillips (bassoon)

image=http://www.operatoday.com/KarliCadel-GGF17-Xerxes-GeneralDress-1794.png

image_description=John Holiday in the title role of The Glimmerglass Festival's 2017 production of Handel's "Xerxes." Photo: Karli Cadel/The Glimmerglass Festival

product=yes

product_title=Glimmerglass: Too Much to Handel?

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: John Holiday as Xerxes

Photos © Karli Cadel/The Glimmerglass Festival

Glimmerglass: Well-Realized Rarity

It is a welcome discovery, chock-full of soaring melodies and surging phrases that recount the moving tale of the six burghers of Calais willing to sacrifice their lives in order to save the city and citizens they love from isolation and destruction. Rodin immortalized the burghers in his famous sculpture, of course, but Donizetti and his librettist Cammarano have also crafted a compelling work of art that is no less impressive. Perhaps its neglect is owing to the extreme interpretive demands on its trio of principal soloists, and here the company outdid itself, peopling its cast with thrilling vocalists.

Soprano Leah Crocetto stars as Eleonora, devoted wife to Aurelio, the mayor’s son missing in the swirling military action. Ms. Crocetto announced herself as a major talent in Rossini’s Maometto II at Santa Fe just a few short years ago. Since then, she has taken on Puccini and Verdi to ever-growing acclaim. With Eleonora, she returns to bel canto with riveting results.

Leah Crocetto as Eleanora and Aleks Romano as Aurelio

Leah Crocetto as Eleanora and Aleks Romano as Aurelio

Not only can she sing accurate and meaningful coloratura with utmost ease, but she also has an expressive range that effectively spans from hushed whisper to raging fury and all points in between. Her generous, creamy spinto has an uncommonly fine luster and appeal, and it is wedded to a simple, sincere acting style, evoking the gifts of the great Caballe. Based on this outing, Leah Crocetto seems poised to be a major international star.

While she may be the recognizable “name” of the cast, the leading role is the activist son Aurelio, and mezzo Aleks Romano matched Crocetto note for note in virtuosity and tonal allure. First, I have never seen a woman in a trouser role look so believably manly. The petite singer is as convincing in her gender-bending as Hilary Swank in her Oscar winning turn as Brandon Teena (Boys Don’t Cry).

Ms. Romano has a searing vocal delivery, her exciting, focused tone appealingly colored by a somewhat urgent vibrato. When Aurelio is riled up (which is often), she hurls inflammatory declamations that ring thrillingly throughout the house. But when she shares loving, concerned duets with Eleonora, Aleks can hone her secure tone to a tender filigree of sound that is heart stopping in its emotional effect. There are two duets in which these two remarkable vocalists sing melting phrases in thirds that are not meant merely for human ears. As their inimitable instruments tumble over each and urge each other to ever greater emotional engagement, well, this is as good as it gets.

Michael Hewitt as Edoardo III

Michael Hewitt as Edoardo III

The role of mayor Eustachio de Sainte-Pierre is exceedingly well served by the imposing bass baritone, Adrian Timpau. His dark, pointed instrument served notice that a major talent has arrived on the scene. Mr. Timpau exuded vocal authority and stylistic acumen, and he mastered every trial of this difficult, lengthy assignment. Mr. Timpau joins the Met’s Lindeman program next year, and his future stardom seems all but assured. Chaz’men Williams-Ali’s ringing, plangent tenor brought much joy to the proceedings as Giovanni de Aire. His sound contributions to the extended ensembles were noteworthy.

Andres Moreno Garcia has a very pleasant, rolling baritone that made much of his brief stage time as Edmondo. Michael Hewett, a memorable Jud (Oklahoma!) the night before, successfully impersonated King Edoardo III. Mr. Hewett has a burnished baritone, which easily served up fine Donizettian style. On this occasion, his very upper register didn’t always turn over to match the ease of his upper-middle. Helena Brown’s imperious, generous soprano made a major impact as Queen Isabella. Talented young bass Zachary Owen was dramatically vested in the cameo of the English Spy, but his potent delivery sometimes pressed to veer off pitch. Joseph Leppek (Giacomo de Wisants), Carl DuPont (Armando), and Rocky Lasky (Filippo) all made solid efforts with their focused, steadfast performances.

In the pit, Joseph Colaneri whipped up a rousing interpretation of this rarity that found his orchestra responding with a vigorously theatrical, stylistically rich reading. Under Maestro Colaneri’s knowing baton, the band was a collaborative partner in the engrossing story, pairing flawlessly with the soloists and urging David Moody’s well-tutored chorus (excellent diction!) to great heights. While the entire orchestra was rightly cheered to the rafters, I have to single out the extended clarinet solo introduction to one of the major set pieces that was a thing of luminous beauty.

Michael Hewitt as Edoardo III and Adrian Timpau as Eustachio de Saint-Pierre

Michael Hewitt as Edoardo III and Adrian Timpau as Eustachio de Saint-Pierre

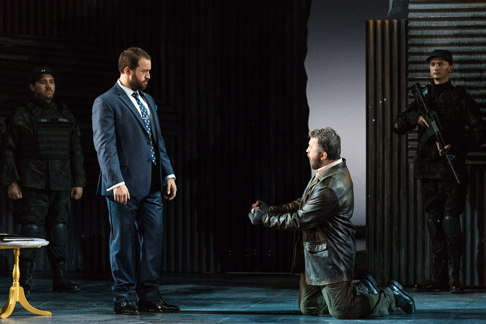

So what does this piece have to say to us in today’s context? If you are director Francesca Zambello, the answer is “plenty.” She has found great resonance in raising the plight of refugees struggling in modern day Calais, and grounding it in the ruined setting of a war torn near eastern town. The first image of James Noone’s evocative set design is seen as we take our seats: a high corrugated, jagged, barbed wire laced sheet metal barrier with “Calais” boldly graffitied onto it serves as an act curtain. A bombed out car lies in state down left.

Ms. Zambello sets her concept up effectively with a staged overture. First, soldiers patrol the fence. When the coast is clear, a desperate intruder clambers over the wall to steal food from the soldiers’ unattended knapsacks. After he is discovered and narrowly escapes, the soldiers regroup across the apron in time to sing the ringing opening chorus. The wall parts and recedes off left and right, revealing the bombed out shell of a three story building that is all too depressingly familiar a visual from the evening news.

Mr. Noone’s hulking set includes a large staircase that the director skillfully uses to create meaningful levels and stage pictures. The turntable is put to good use as it spins the structure to suggest different locales. Costume designer Jessica Jahn’s carefully selected, character specific street wear for the downtrodden, and tailored uniforms and business wear for the privileged were aptly inspired by today’s front page photos. Mark McCullough’s austere lighting design was calculated to highlight important dramatic moments, balancing well-selected specials with murky shadow effects. This was a most convincing feat of story telling, making a potent case for a forgotten 19th century opera by making it all too relevant in today’s world. By making the character relationships so intensely believable and their predicament so universally human, Francesca has even managed to gloss over the pretty big flaw in the denouement.

Edoardo has adamantly refused over and over to spare the burghers’ lives and indeed, soldiers point assault rifles menacingly at the intended targets throughout the extended penultimate ensemble. Queen Isabella has pleaded with husband Edoardo to spare them, but he unceremoniously rejects her. Musically, dramatically, the piece churns inexorably to certain tragedy. Then, in the briefest of moments that is the operatic equivalent of “honey, c’mon now. . .” Isabella gets Edoardo to say the shrugging equivalent of “Oh. . .okay.” And, basta, everyone is free. Never you mind. This talented group has such total commitment to the piece, and they believe in it so strongly, that damn if we don’t suspend our disbelief as well.

There is such a wealth of musical riches in The Siege of Calais (at least with this consummate team) that it is astonishing it has take so long to resurface. Now that the enterprising Glimmerglass Festival has emphatically demonstrated there are singers capable of handling it, and proven there are audiences ready to be thrilled by it, maybe it will find the widespread recognition it deserves.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Eustachio de Sainte-Pierre: Adrian Timpau; Eleonora: Leah Crocetto; Giovanni de Aire: Chaz’men Williams-Ali; Pietro de Wisants: Makoto Winkler: Aurelio: Aleks Romano; English Spy: Zachary Owen; Giacomo de Wisants: Joseph Leppek; Armando: Carl DuPont; Edmondo: Andres Moreno Garcia; Edoardo III: Harry Greenleaf; Isabella: Helena Brown; Filippo: Rocky Lasky; Conductor: Joseph Colaneri; Director: Francesca Zambello; Set Design: James Noone; Costume Design: Jessica Jahn; Lighting Design: Mark McCullough; Hair and Make-up Design: J. Jared Janas, Dave Bova; Chorus Master: David Moody

image=http://www.operatoday.com/KarliCadel-GGF17-Siege-GeneralDress-3513.png

image_description=L to R: Aleks Romano as Aurelio, Adrian Timpau as Eustachio de Saint-Pierre, Makoto Winkler as Pietro de Wisants, Leah Crocetto as Eleanora, and Chaz'men Williams-Ali as Giovanni d'Aire in The Glimmerglass Festival's 2017 production of the American premiere of Donizetti's "The Siege of Calais." Photo: Karli Cadel/The Glimmerglass Festival

product=yes

product_title=Glimmerglass: Well-Realized Rarity

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: L to R: Aleks Romano as Aurelio, Adrian Timpau as Eustachio de Saint-Pierre, Makoto Winkler as Pietro de Wisants, Leah Crocetto as Eleanora, and Chaz'men Williams-Ali as Giovanni d'Aire

Photos © Karli Cadel/The Glimmerglass Festival

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in Salzburg

Though it really was not crumbling, decaying socialist housing, it was actually a vagina shaped cavity into which thrust two phallic platforms, in and out repeatedly throughout this long, loud, gross evening.